PRIVATIZATION OF PEACEKEEPING

A C A S E S T U D Y O N T H E U S E O F P R I V A T E M I L I T A R Y A N D S E C U R I T Y C O M P A N I E S I N U N I T E D N A T I O N S P E A C E K E E P I N G M I S S I O N M O N U C / M O N U S C O I N T H E D E M O C R A T I C R E P U B L I C O FC O N G O

Master Thesis

Leiden University - Faculty of Governance and Global Affairs

Program: Master Crisis and Security Management 2017/2018

Name: Lyke Kruizinga

Student number: s1927604

Thesis Supervisor: Dr. J. Matthys

Second Reader: Dr. G.M. van Buuren

Date: 10-06-2018

Page - 2 - of 81

Abstract

This research aims to provide contextualized insight into the privatization of the United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUC), later renamed as United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO), and to build explanations about the causes of privatization within this single case with use of three theoretical models. Further, the goal of this research is to test which theoretical model provides the highest explanatory value of the phenomenon privatization in this particular case.

Preliminary to the analysis, a theoretical framework is provided in which the three theoretical models that are used in this research, the functionalist model, the political-instrumentalist model, and the ideationist model, are discussed. The functionalist model argues that states use PMSCs as a way of realizing their security goals in an effective and cost-efficient way, pushed by complexity-enhancing conditions and resource dependence. Subsequently, the political-instrumentalist model argues that states aim at covering or downplaying their role and responsibility in order to reduce political costs by delegating tasks to PSMCs. Finally, the ideationist model argues that two approaches towards the appropriate roles of state and non-state in the provision of security can be noticed, namely a laissez-faire neoliberal approach and a state-interventionist approach. Additionally, the methodology chapter provides the operationalization of this research in which the three theoretical models are adapted and formed into measurable factors that will be used in the analysis. Hereafter, the operationalized models are applied to the case of MONUC/MONUSCO in order to find the theoretical model with the highest explanatory value and to provide contextualized insight into this specific case.

Page - 3 - of 81

Table of Contents

List of Tables ... 5

List of Figures ... 6

List of Abbreviations ... 7

-Part 1: Introduction ... 8

-1.1The Use of Private Military and Security Companies in Peacekeeping Operations ... 8

-1.2General Research Question and SubQuestions ... 9

1.3 Academic Relevance ... 9

1.4 Societal Relevance ... 9

1.5 Thesis Outline ... 10

-Part 2: Theoretical Framework ... 11

2.1 Defining Private Military and Security Companies ... 11

2.2 Privatization of peacekeeping ... 13

-2.3 Kruck’s theoretical models, systemizing the theoretical debate on the privatization of security ... - 17 2.3.1 Functionalist model... 18

2.3.2 Politicalinstrumentalist model ... 19

2.3.3 Ideationist model... 20

-Part 3: Methodology ... 22

3.1 Research Design ... 22

3.2 Case Selection ... 23

3.3 Analysis ... 24

3.4 Data collection ... 24

3.5 Operationalization ... 25

3.5.1 Operationalization of the functionalist model ... 26

3.5.2 Operationalization of the politicalinstrumentalist model ... 27

3.5.3 Operationalization of the ideationist model ... 28

3.5.4 Summary of operationalization ... 30

3.6 Validity and Reliability ... 31

-Part 4: Analysis ... 33

-Chapter 1: Context of the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo and its peacekeeping mission MONUC/MONUSCO ... 33

-Page - 4 - of 81

2.1 Complexity ... 36

2.1.1 Complexity of MONUC/MONUSCO ... 36

2.1.2 Technological changes during MONUC/MONUSCO ... 37

2.2 Resource dependence ... 39

2.2.1 Provision of material and immaterial military and security resources by PMSCs ... 39

2.3 Costefficiency ... 44

2.3.1 MONUC/MONUSCO’s expenditures and budget cuts ... 44

2.3.2 Benefits of the contracted PMSCs ... 46

2.3.3 Material costs of the contracted PMSCs ... 48

2.4 Conclusion of the functionalist model analysis ... 49

Chapter 3: Analysis of the politicalinstrumentalist model ... 51

3.1 Depoliticisation by delegation ... 51

3.1.1 Democratic oversight and control mechanisms ... 51

3.1.2 Covering and downplaying United Nations’ role and responsibility ... 53

3.2 Conclusion of the politicalinstrumentalist model analysis ... 56

Chapter 4: Analysis of the ideationist model ... 57

4.1 Laissezfaire (neo)liberal conception ... 57

4.1.1 Minimal tasks for the United Nations, maximal tasks for PMSCs ... 57

4.1.2 Marketbased solutions for peacekeeping ... 59

4.2 Stateinterventionist conception ... 60

4.2.1 Reluctance towards the private military and security sector ... 60

4.2.2 United Nations’ own strength and capacity ... 61

4.3 Conclusion of the ideationist model analysis ... 62

-Part 5: Conclusion and Discussion ... 64

Bibliography ... 67

Appendices ... 81

-Page - 5 - of 81

List of Tables

Table 1: UN Peacekeeping List of Operations ... 23

-Table 2: Summary of operationalization ... 30

-Table 3: Overview of PMSCs contracted in MONUC/MONUSCO* ... 41

-Table 4: MONUSCO Expenditures ... 44

-Page - 6 - of 81

List of Figures

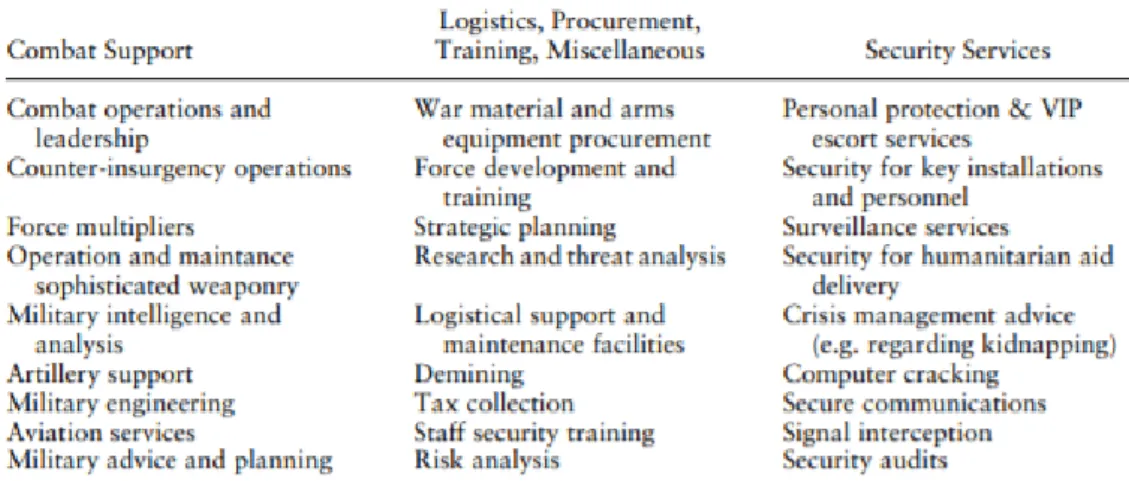

Figure 1: Services performed by Private Military and Security Companies ... 12

-Figure 2: Linkages and Grey Areas ... 14

-Figure 3: Operationalisation scheme ... 26

-Page - 7 - of 81

List of Abbreviations

AFDL Alliance des forces democratiques pour la liberation du Congo-Zaïre

DPA Department of Political Affairs

DPKO Department of Peacekeeping Operations DRC Democratic Republic of Congo

FDLR Forces Démocratiques de Libération du Rwanda

MONUC United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

MONUSCO United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo

ONUB United Nations Operation in Burundi PAE Pacific Architects and Engineers

PMC Private Military Company

PMSC Private Military and Security Company

PSC Private Security Company

UAV Unmanned Aerial Vehicle

Page - 8 - of 81

Part 1: Introduction

1.1The Use of Private Military and Security Companies in Peacekeeping Operations

Ranging from international conflicts in the Middle-East to violent clashes in several countries in Africa, many countries in the world are confronted with- and involved in international conflicts. Often, both public as private actors are involved in these armed conflicts (Linti, 2016). One of the public actors that is often involved in international conflicts, is the United Nations (UN). This organisation can be perceived as the largest and most powerful intergovernmental organisation in the world and is among others focused on maintaining international peace and security through UN peacekeeping missions. Through these peacekeeping missions, the UN supports countries in navigating from conflict to peace (UN.org, 2018g).

The UN increasingly deploys Private Military and Security Companies (PMSCs) in multilateral peacekeeping missions (Pingeot, 2012). These PMSCs provide armed and unarmed services such as protective security, peacekeeping training, counselling, security training and intelligence (Østensen, 2013). For instance, the UN outsourced a major part of its peacekeeping missions to PMSCs in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO), Haiti (MINUSTAH) and Cote d’Ivoire (UNOCI) (Pingeot, 2014). The UN contracted among others the companies G4S, DynCorp and Delta Protection (Pingeot, 2014). The contracts between the UN and PMSCs are worth millions of dollars. However, it is evident that these PMSCs do not always have the best reputation. For example, DynCorp International is known for its role in the prostitution scandal in a UN mission in Bosnia in the 1990s (Pingeot, 2012). Hence, the privatization of peacekeeping as a phenomenon and its causes and conditions create an interesting starting point for research.

Page - 9 - of 81

peacekeeping in this particular case. The governmental models that will be used are the functionalist model, the public-instrumental model and the ideationist model (Kruck, 2014).

1.2General Research Question and Sub-Questions

In light of the preceding introduction, this research aims to answer the following explanatory research question:

To what extent can the theoretical models of Kruck (2014) explain the privatization of United Nations peacekeeping mission MONUC/MONUSCO in the Democratic Republic of Congo?

1.3 Academic Relevance

This research attempts to combine the academic discourse on privatization of peacekeeping and public-private cooperation with functionalist, political-instrumentalist and ideationist theories. In that regard, the academic debate surrounding this phenomenon of outsourcing to PMSCs is mostly focused on advantages, disadvantages, legal impediment and issues of democratic and political accountability concerning PMSCs. It is notable that less research is done on the causes and conditions for the use of PMSCs (Kruck, 2012). More importantly, the privatization of peacekeeping, and especially the causes and conditions for the use of PMSCs in peacekeeping, is an even lesser researched topic. In order to fill this research gap and contribute to the academic debate, this research analyses three theoretical models on the privatization of security to explain the causes and conditions of this phenomenon within one specific case, and aims to find the model with the highest explanatory value for the phenomenon of privatization of peacekeeping within that case. As the goal of this research represents a detailed look into the privatization of peacekeeping within one specific case, and aims at hitherto unexplored causes and conditions for the use of PMSCs by the UN, this research is of considerable academic significance. In conclusion, this thesis aims to make a contribution to academic knowledge on an under-researched topic and intends to provide a basic theoretical framework that can be applied to other cases in the academic world of privatization and peacekeeping.

1.4 Societal Relevance

Page - 10 - of 81

difficult for the public and the media to follow their activities and procedures of the PMSCs in peacekeeping operations. Therefore, contracting PMSCs evoke concerns of public and democratic accountability, also in terms of public values. Further, the issue of political accountability is relevant. The global environment of multilateral peacekeeping missions in which PMSCs are operating cross-boundary, demands clear accountability mechanisms (Lilly, 2000). Furthermore, this research is relevantin terms of human rights and ethical issues. Some PMSCs are known by their misconduct in terms of violence, human rights abuses and financial irregularities (Pingeot, 2012). And what to think of ethical questions about whether PMSCs will replace the government’s monopoly of violence as the main guarantor of security?

1.5 Thesis Outline

Page - 11 - of 81

Part 2: Theoretical

F

ramework

In light of the broad and complex concepts and theoretical models of this research, it is necessary to narrowly define and conceptualize them. First of all, the phenomenon of Private Military and Security Companies will be defined. Hence, the concept of peacekeeping and in specific the privatization of peacekeeping will be clarified. Subsequently, Kruck’s (2014) theoretical models and concepts will be explained. These theoretical models form the theoretical framework of this thesis, which will subsequently be applied to the case.

2.1 Defining Private Military and Security Companies

The private military and security industry is a broad spectrum of groups, organizations and services including militias, mercenaries, armed groups, PSCs and PMCs (Schreier & Caparini, 2005). This research examines one specific part of the private military and security industry, namely Private Military and Security Companies (PMSCs). These companies cover a wide range of people, activities, and services. Strictly seen, Private Military Companies (PMCs) and Private Security Companies (PSCs) are two different types of companies that can be distinguished in various ways (Schreier & Caparini, 2005). One approach is to differentiate the companies by their activity level: the companies that engage in combat operations are “active” and those that defend territories and/or provide training and intelligence are on a “passive” activity level (Schreier & Caparini, 2005). Another approach that can distinguish PMCs and PSCs, is the differentiation between ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ services. Hence, PSCs can be seen as suppliers of soft services such as logistics and PMCs as suppliers of hard services such as military training (Gumedze, 2011). The industry for ‘soft’ services exists for a lot longer than the PMCs market and is also larger and more competitive. The PSC industry is mostly focused on trade in unarmed professional services related to protection of property and personnel whereas the PMC industry is mostly focused on having an (armed) military impact on a specific conflict (Lilly, 2000).

Page - 12 - of 81

Caparini, 2005). Some of these services, such as logistic support and intelligence gathering, are similar to those that PSCs provide. Moreover, PSCs increasingly operate in conflict situations including hostile fire whereas this is originally a classic military mission (Schreier & Caparini, 2005; Lilly, 2000). Similarly, the UN Working Group on the use of mercenaries stated that:

Private military and security companies continue to provide a wide range of services, including personnel protection, site security and convoy security for military and civilian personnel working for international institutions, Governments or private entities, as well as policing and security protection services, intelligence data collection and analysis, private administrative of prisons, interrogation of detainees and reportedly covert operations. (UN Secretary General, 2010, August 25, p. 4).

Despite the blurred lines between PMCs and PSCs, Singer (2008) categorized PMCs and PSCs by using a ‘tip of the spear’ analogy. He distinguished three types of private military firms (PMFs): military provider firms (type 1), military consultant firms (type 2) and military support firms (type 3). The tip of the spear indicates the front line were Type 1 firms provide services

focused on implementation and outcomes. Type 2 firms provide advice and training services and Type 3 firms, stationed at the end of the spear, provide supplementary services such as logistical functions (Singer, 2008). PSCs fall under Type 3 firms because they have a non-combative role but are operating close to the combat zone (Mbadlanyana, in Gumedze, 2011). A more specific categorization of the services performed by PMCs, is provided by Bures (2005). This categorization, that is based on the functions performed by PMCs in the 1990s, is demonstrated in Figure 1 hereunder.

Page - 13 - of 81

According to Figure 1, PMCs perform services in the categories of combat support (1); logistics procurement, training, miscellaneous (2); and security services (3). As security services are included in the categorization of Bures (2005), and the aim of this research is to examine the causes for the privatization of peacekeeping in MONUC/MONUSCO rather than study the difference between PMCs and PSCs, the two are merged into the concept of a Private Military and Security Company. Hence, in accordance to the Montreux Document (2008) that merges PMCs and PSCs into PMSCs and identifies them as “private business entities that provide military and/or security services, irrespective of how they describe themselves” (Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs and the International Committee of the Red Cross, 2009, p. 9), this research will use the following definition of a PSMC: ‘a private business entity performing military and/or security services in one, two or all of the three categories of combat support (1), logistics, procurement, training, miscellaneous (2) and security services (3)’. The categorization of services performed by PMSCs (Figure 1) will be used to filter the PMSCs that are contracted by the UN in peacekeeping mission MONUC/MONUSCO in order to provide a clear image of the PMSCs’ performed military and/or security services.

2.2 Privatization of peacekeeping

At the end of the 1970s different governments around the world started to use privatization, or outsourcing, public-private partnerships to solve their various security issues (Badell-Sánchez, 2018). The rise in the privatization of security and its industry, was caused by “a shift in the logic of sovereignty” (Neocleous, 2007, p. 345). The era of state sovereignty has changed,

Page - 14 - of 81

are the Children’s fund, the World Food Program, and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Moreover, the UN Procurement Division, which is involved in contracting PMSCs for UN peacekeeping missions, is a large client of PMSCs (Pingeot, 2012).

United Nations peacekeeping missions have to be understood in the wider context of peacekeeping. In general, there is little agreement between researchers, governments and international organizations about the definition of peace operations and terms such as peacekeeping, peacemaking and peacebuilding (Bellamy, Williams, & Griffin, 2010). The UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) places peacekeeping among a ‘range of peace and security activities’, namely conflict prevention, peacemaking, peacekeeping, peace enforcement and peacebuilding (UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations, 2008). According to DPKO peacekeeping is:

a technique designed to preserve the peace, however fragile, where fighting has been halted, and to assist in implementing agreements achieved by the peacemakers. Over the years, peacekeeping has evolved from a primarily military model of observing cease-fires and the separation of forces after inter-state wars, to incorporate a complex model of many elements – military, police and civilian – working together to help lay the foundations for sustainable peace. (Department of Peacekeeping Operations, 2008, p. 18).

However, the DPKO points out the blurred boundaries between conflict prevention, peacemaking, peacekeeping, peacebuilding and peace enforcement. Figure 2 demonstrates the linkages and blurred lines of the five ‘peace and security activities’.

Page - 15 - of 81

According to the DPKO (2008) peacekeeping operations are rarely limited to only one type of activity. As can be seen in Figure 2, UN peacekeeping operations are deployed to play an active role in the implementation of a cease-fire. Often, they also play an active role in peacemaking efforts. Furthermore, UN peacekeeping operations are allowed to use force at tactical levels to defend themselves and their mandates (UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations, 2008). This can also be found in the three basic principles of UN peacekeeping operations:

1. Consent of the parties – The consent of all the main parties to the conflict provides the UN with necessary freedom of action to carry out its mandate.

2. Impartiality – This principle is crucial in maintaining both consent and cooperation of all parties to avoid undermining of the operation’s credibility and legitimacy.

3. Non-use of force except in self-defense and defense of the mandate – As UN peacekeeping operations are not meant as an enforcement instrument, force may only be used at the tactical level in self-defense and defense of the mandate, authorized by the Security Council (UN.org., 2018c).

Whereas the definition of peacekeeping by the DPKO does not explicitly mention this use of force nor the other basic principles of UN peacekeeping, the definition of Goulding (1993) is more explicit for the purpose of this research. Although his definition does not include peace operations by non-UN actors such as regional organizations according to Bellamy et al. (2010), it will function as the definition of peacekeeping in this research because of it specific focus on UN peacekeeping operations. Goulding (1993) defines peacekeeping as:

Field operations, established by the United Nations, with the consent of the parties concerned, to help control and resolve conflicts between them, under United Nations command and control, at the expense collectively of the member states, and with military and other personnel and equipment provided voluntarily by them, acting impartially between the parties and using force to the minimum extent necessary. (Goulding, 1993, p.455).

Page - 16 - of 81

peacekeeping. Today, the use of PMSCs in United Nations peacekeeping missions is a common phenomenon (Lynch, 2010). A steady rise in the number of PMSCs contracts from 2006 to present is demonstrated in UN data1, summarized by Pingeot (2014), although he argues that this data is incomplete and ‘greatly understate the overall totals’ (Pingeot, 2004, p. 23). A major reason given for the increasing use of PMSCs since the 1990s is the UN Member States’

unwillingness or inability to respond to the growing number of conflicts. Hence, PMSCs could offer solutions to political, financial and institutional constraints faced by the UN (Lilly, 2000). Moreover, Brooks & Laroia (2005) argue that PMSCs have a ‘force-multiplier effect’: by supporting regular peacekeeping troops, the troops become more effective and the number of troops necessary are reduced.

PMSCs are frequently used to protect UN field offices, personnel and warehouses, but also provide logistical services such as managing transportation systems (Brooks & Laroia, 2005). Østensen (2011) argues that “the level of PMSC contracting appears to vary, depending on both the level of difficulty of the mission and the often corresponding difficulty of getting the needed personnel” (Østensen, 2011, p. 15). Furthermore, many UN contracts with PMSCs in

peacekeeping operations seem to involve more than one service type, ranging from logistic

services to information-gathering services and often provided as a combination (Østensen, 2011). The UN itself acknowledged that:

The United Nations has long used private security companies to secure premises and assets against criminal activities. In recent years, however, faced with demands from Member States to carry out mandates and programmes in high-risk environments, in addition to increased evidence that the United Nations is a specific target in some such environments, organizations of the United Nations system have, as a last resort, contracted armed private security companies to protect United Nations personnel, premises and assets. (UN Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions, 2012, December 7, p. 7)

It is important to notice that PMSCs are not always hired directly by the UN, but also may be seconded to a peace operation by an UN Member State or third party (Østensen, 2011). The latter is a common practice concerning US contributions to the UN. Mostly, the US State

Page - 17 - of 81

Department recruits police personnel from private companies and subsequently supply police services from private contractors to international peacekeeping. Nonetheless, the procurement of PMSCs services for peace operations is mostly done by the UN directly from its headquarters and in the field (Østensen, 2011). Since the scope of this research is limited to UN policies and practices rather than Member States’ policies, it will only study the causes and conditions for direct UN procurement of PMSC services during MONUC/MONUSCO.

Furthermore, this thesis broadly refers to the ‘United Nations’ as the main actor in procurement of PMSC services to the mission. However, it is important to notice that the UN cannot be perceived as an unitary actor as the UN system consist of various organisations, departments and programmes. Nonetheless, for the simplicity of this research the term United Nations will be used when referring to UN policies, practices, and viewpoints.

2.3 Kruck’s theoretical models, systemizing the theoretical debate on the privatization of

security

Gómez del Prado (2011) points out the discussion about the roles of PMSCs, the operating norms and the monitoring of their activities. He states that these issues need to be addressed both at national and international level (Gómez del Prado, 2011). A number of studies focus on these problems of national and international regulation and legal issues of PMSCs (Leander, 2010; Krahmann, 2005; Lilly, 2000; Janaby, 2015; Sossai, 2014). Other studies focus more on issues of democratic and political accountability regarding the use of PMSCs and the monopoly of violence and security provision (Pingeot, 2012; Krahmann, 2008). Hence, a lot of studies focus on the disadvantages and limits of PMSCs. However, some authors studied the advantages of using PMSCs, for example Genser and Garvie (2015) who examined the possibility to use them as a rapid reaction force.

Page - 18 - of 81

chapters will discuss these theoretical models on the causes and conditions for the use of PSMCs.

2.3.1 Functionalist model

One theoretical model that Kruck developed to explain the privatization of security is the

functionalist model. This is an explanatory model based on a combination of the principal-agent theory and the resource-dependence theory. The functionalist model is focused on problem-driven privatization and argues that states use PMSCs as a way of realizing their security goals in an effective and cost-efficient way. This reliance is a consequence of increased asymmetric warfare at the end of the Cold War and the military affairs revolution (Kruck, 2014). Therefore, complexity is the first main concept of this model and entails “the complexity-enhancing conditions of deep and rapid technological changes in warfare, volatile security environments and asymmetric violent conflicts” (Kruck, 2014, p. 115).

The increased complexity of rapid technological changes in warfare and asymmetric violent conflicts ensures that states increasingly use PMSCs because they sometimes lack the skills and expertise that is necessary to manage complex security situations (Kruck, 2014). Therefore, states are increasingly dependent on PMSCs resources for achieving their security goals effectively. The use of PMSCs increases the flexibility and response rate to complex security problems of states as PMSCs possess professional expertise, skills and are available on the short-term (Kruck, 2014). Hence, the second main concept of this model is resource dependence and entails that principals tap their agents’ resources due to lack of own resources (Kruck, 2014).

Page - 19 - of 81

2.3.2 Political-instrumentalist model

Next to the functionalist model, Kruck developed a second model for explaining the privatization of security, namely the political-instrumentalist model. The political-instrumentalist model entails a strategy that is focused on reducing political costs instead of increasing effectiveness and cost-efficiency (Kruck, 2014). From the perspective of this model, PMSCs are “instruments for the reduction of political costs accruing to governments from warfare in the context of democratic politics” (Kruck, 2014, pp. 116-117). In fact, governmental actors can profit from a lesser form of transparency and media coverage when using PMSCs, compared to the use of public forces. According to the political-instrumentalist model governments “seek to keep or even expand their policy autonomy from other legislative and judiciary actors, as well as the broader public” (Kruck, 2014, p. 117). Hence, their popularity in the broader public plays a contributing role to the choice of hiring PMSCs (Kruck, 2014). Noticeable from the perspective of this model, is that governments can profit from the PMSCs’ lack of transparency and accountability. To achieve this lack of transparency and accountability, democratic oversight and control mechanisms are avoided by the principals. Hence, “privatization serves to cover or downplay the roles and responsibilities of governments” (Kruck, 2012, p. 118). The political-instrumentalist model argues that privatization or delegation of security provision to PMSCs is the principals’ strategy of depoliticisation (Kruck, 2014).

In that regard, depoliticisation entails that highly political security measures are distanced from other, often transparent, actors such as parliamentary, civil society and the media. Hence, the political-instrumentalist model argues that security tasks are transferred from the public to the private sector with the aim of reducing transparency, distributing accountability, avoiding democratic oversight and control mechanisms, and enhancing political autonomy on security provision (Kruck, 2014).

Page - 20 - of 81

2.3.3 Ideationist model

The third theoretical model that will be used in this research is the ideationist model. This model is focused on norms, ideas and conceptions of the state (Kruck, 2014). In contrast to the other two models, the ideationist model locates the causes of privatization in the ascendancy of the neoliberalism idea-system instead of in material conditions. From the perspective of this model, transnational and national conceptions define “the appropriate roles of state and non-state (market) actors in fulfilling security functions” (Kruck, 2014, p. 119).

The model divides the conceptions of the state, which define the actor who is appropriate for the provision of security functions, in a laissez-faire (neo)liberal conception and a state-interventionist conception. The laissez-faire (neo) liberal conception implies that the privatization of security is not a priori confined to the state but may include multiple (private) actors. This conception “aims at a minimal state, which leaves as many tasks as possible to the individual or the private sector” (Kruck, 2012, p. 119). Moreover, the laissez-faire (neo)liberal conception implies that non-state market actors are the best option to fulfil security functions. Hence, the laissez-faire (neo)liberal conception implies that a state aims at outsourcing maximal tasks to the private sector. Moreover, a state actively tries to find market-based solutions for security provision. Important to notice is that non-core functions will be outsourced earlier and faster than military core functions as “neoliberal ideas diffuse first to the margins of armed forces’ activities before they may migrate into core military areas of warfare” (Kruck, 2014, p. 120).

The opposing approach towards the appropriate roles of state and non-state in the provision of security, the state-interventionist conception, argues that peacekeeping is confined to the state rather than to the market as the state is richer in competencies and resources. Hence, a state with a state-interventionist conception will rather demonstrate reluctance towards the private sector as it “has less confidence in the steering capacities of the market” (Kruck, 2014, p. 119). To summarize, the ideationist model brings forth the following hypothesis:

Page - 21 - of 81

will occur later, more slowly and more reluctantly than will be the case with non-core functions (Kruck, 2014, p. 120)

Page - 22 - of 81

Part 3: Methodology

The precedent part discussed the potential theoretical explanations for privatization of peacekeeping. The aim of this thesis is to research to what extent these theoretical explanations can explain the privatization of UN peacekeeping mission MONUC/MONUSCO. This part will focus on the methodological substantiation, data collection and the operationalisation of the models and concepts of this research. Further, the validity and reliability of this research will be discussed, including an elaboration on generalization.

▪ Research design: Single case study ▪ Sampling strategy: Purposive sampling

▪ Unit of analysis: UN peacekeeping mission MONUC/MONUSCO

▪ Unit of observation: Documents on UN peacekeeping mission MONUC/MUNUSCO ▪ N: 7,14% (1 out of all 14 current UN peacekeeping missions, 2018) ▪ Data gathering: Document analysis

3.1 Research Design

The main purpose of this study is to provide contextualized insight into the privatization of the UN peacekeeping mission MONUC/MONUSCO in the Democratic Republic of Congo and to build explanations about the causes of privatization within this case with use of three theoretical models. Further, the goal is to test which theoretical model has the highest explanatory value of the phenomenon privatization in this particular case. In order to achieve this goal, a single case study design is chosen with an explanatory aim. In order to explain the phenomenon of privatization within the specific case of UN peacekeeping mission MONUC/MONUSCO, a single within-case study will be conducted. This study will examine the factors that could produce the phenomenon of privatization in the case. This means that the theoretical end is on the within-case level and is therefore bound to that specific case (Rohlfing, 2012).

Page - 23 - of 81 3.2 Case Selection

The UN peacekeeping operation areas are Africa, Americas, Asia and the Pacific, Europe and the Middle East. In total, the UN has completed 56 peacekeeping missions in these areas, whereof most in Africa (UN.org., 2018e). It is important to distinguish between missions led by the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) and missions led by the UN Department of Political Affairs (DPA). Currently, the DPKO has 14 peacekeeping missions running in the whole world, whereof 7 in Africa (UN.org., 2018e). The DPA manages 13 field-based political missions and provides guidance and support to traveling envoys and special advisers of the Secretary-General in Africa, Central Asia and the Middle East (UN Department of Political Affairs, 2018).

This research focuses on 1 of the 14 peacekeeping missions led by the DPKO (N= 7,14%), namely MONUSCO, formerly called MONUC until 2010. MONUC/MONUSCO is an ongoing UN peacekeeping mission, operating in the Democratic Republic of Congo since 1999. Hence, because of the ongoing character of this peacekeeping mission, and the available data on UN procurement of PMSCs which only reaches 2016, the research scope of this thesis is set from 1999 until 2017. Table 1 demonstrates the exact details of the case that will be used in this research.

Table 1: UN Peacekeeping List of Operations

Mission Abbreviation Name Peacekeeping Mission Start Date End Date

MONUC United Nations Organization

Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

November 1999

June 2010

MONUSCO United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

July 2010 Present

Source: UN.org.,2018f, List of Peacekeeping Operations 1948-2018

Page - 24 - of 81

the UN hired PMSCs for three main categories of services in the case of MONUC/MONUSCO, namely in the field of security, logistics and frontline troops (Badell-Sánchez, 2018). Important to notice is that the UN contracted both armed and unarmed PMSCs during MONUC/MONUSCO. Hence, this specific case is useful to test the theoretical frameworks because privatization is clearly present.

Consequently, the unit of analysis is the privatization of the UN peacekeeping mission MONUC/MONUSCO embedded within the case and context of the mission. Furthermore, the units of observation are all relevant documents of the UN peacekeeping mission MONUC/MONUSCO.

3.3 Analysis

The case of MONUC/MONUSCO is studied through document analysis. This analytic approach concerns using operationalized measures, retrieved from concepts of three theoretical model, as analytic factors to verify if they can be found in the data. Each of the main concepts of the theoretical models, the functionalist model, the political-instrumentalist model, and the ideationist model, are operationalized into factors. Hence, each of these factors and their operationalized definitions are linked to designed questions that will measure these factors within the specific case of this research. In that regard, the explanatory value of each theoretical model can be analysed and eventually provide an answer to the main research question of this thesis.

The operationalization of this research will be discussed further in Chapter 3.4. Moreover, as the context of the conflict in the DRC and its peacekeeping mission MONUC/MONUSCO is vital to understand the situations and developments that are discussed in this thesis, this context will be discussed preliminary to the analysis of the three models.

3.4 Data collection

Page - 25 - of 81

concerning the specific case of this research. Additionally, several components of the UN website are used to provide relevant background information for this research. Further, acedemic literature is accessed to provide all additional information to this research. Finally, documents of the UN Procurement Division and Annual Statistical Reports are used to provide all relevant contracts and purchase orders with PMSCs during MONUC/MONUSCO till 2017 as the reports on UN procurement in 2017 and 2018 are not published yet. Important to notice is that the data on UN procurement of PMSCs’ services in MONUC/MONUSCO might be partial because the UN does not clearly list all the PMSCs that were contracted for each specific mission. Nonetheless, this research does include all contracts that were possible to track down and tries to give an insight as complete as possible.

3.5 Operationalization

Page - 26 - of 81 Figure 3: Operationalisation scheme

3.5.1 Operationalization of the functionalist model

First of all, the functionalist model is based on problem driven privatization and consists of the factors complexity, cost-efficiency and resource dependence. The first factor complexity, is conceptualized as ‘complexity-enhancing conditions of deep and rapid technological changes in warfare, volatile security environments and violent non-state actors’. The following two questions are designed to be able to measure this factor within the case of MONUC/MONUSCO and will address the complexity-enhancing conditions that motivate state actors to contract PMSCs:

2. To what extent was the UN confronted with unstable, unpredictable and readily changing security situations, including violent non-state actors, in the conflict of the DRC during MONUC/MONUSCO and to what extent did the UN contract PMSCs to deal with those situations?

Page - 27 - of 81

The second factor of the functionalist model is resource dependence. This variable is defined as ‘a situation of dependence on someone else’s resources, because of lack of own resources’. The following question will examine UN’s resource dependence during MONUC/MONUSCO: 1. What material and/or immaterial military and security resources did contracted PMSCs provide to the UN and to what extent did the UN lack those material and/or immaterial military and security resources during MONUC/MONUSCO?

The third and last factor of the functionalist model is cost-efficiency, which is ‘a situation in which the benefits (outputs) are larger than the material costs (inputs)’. First of all, it is important to examine if the UN was confronted with budget-saving pressures because this could possibly lead to searching for cost-efficient solutions:

1. What were MONUC/MONUSCO’s expenditures and to what extent was the UN confronted with budget-saving pressures during MONUC/MONUSCO?

The following two questions are designed to measure the inputs and outputs of the use of PMSCs during MONUC/MONUSCO. In the end, a comparison between those inputs and outputs to measure whether cost-efficiency is a motivator for the use of PMSCS will be provided in the sub-conclusion.

2. To what extent did the contracted PMSCs provide benefits (outputs) such as functional specialisation to the UN during MONUC/MONUSCO?

3. What were the material costs (inputs) of the contracted PMSCs during MONUC/MONUSCO?

3.5.2 Operationalization of the political-instrumentalist model

The second model is focused on the reduction of political costs and is based on the concept depoliticisation by delegation. This factor isdefined as ‘a situation in which the principal aims at covering or downplaying its role and responsibility in order to reduce political costs by delegating tasks to contracted agents’.

Page - 28 - of 81

transparency (and thereby reducing political costs) by delegating tasks to contracted PMSCs, and shifted its role and responsibility to contracted PMSCs or not:

1. To what extent did the UN apply democratic oversight and control mechanisms to contracted PMSCs during MONUC/MONUSCO?

2. To what extent did the UN cover or downplay its role and responsibility by contracting contracted PMSCs during MONUC/MONUSCO?

3.5.3 Operationalization of the ideationist model

The third model is focused on transnational norms and ideas defining the role of state and non-state actors and is based on the factors laissez-faire (neo)liberal conception and state-interventionist conception. This first factor is conceptualized as ‘a privatization-friendly conception that peacekeeping is not a priori confined to the state but may include multiple (private) actors’. This conception is the opposite of latter variable, the state-interventionist conception of the state, which is more reluctant to the privatization of security and defined as ‘the privatization-reluctant conception that peacekeeping is confined to the state’.Important to notice is that for the purpose of this research the UN is perceived as ‘the state’ as it is an intergovernmental organisation that contracts the private actor and the provision of security is further specified as the provision of peacekeeping.

Hence, the main question that has to be answered to test these factors is whether the UN approach to peacekeeping during MONUC/MONUSCO can be identified as a laissez-faire (neo) liberal approach or more as a state-interventionist approach. In order to answer this question. the following questions and sub-questions are designed:

Laissez-faire (neo)liberal conception

Can the UN approach to peacekeeping during MONUSCO be identified as a laissez-faire (neo) liberal approach?

a. To what extent did the UN include multiple (private) actors for peacekeeping during

MONUC/MONUSCO?

Page - 29 - of 81 State-interventionist conception

Can the UN approach to peacekeeping during MONUSCO be identified as a state-interventionist approach?

a. To what extent did the UN demonstrate reluctance towards the private military and industry during MONUC/MONUSCO?

Page - 30 - of 81

3.5.4 Summary of operationalization

Table 2: Summary of operationalization

Model Factor Operational Definition Measurement Source

Functionalist model (problem-driven privatization for effective and cost-efficient pursuit of security goals)

Complexity Complexity-enhancing

conditions of deep and

rapid technological

changes in warfare,

volatile security

environments and violent

non-state actors.

1. To what extent was the UN

confronted with unstable, unpredictable

and readily changing security situations,

including violent non-state actors, in the

conflict of the DRC during

MONUC/MONUSCO?

2. To what extent did the UN

incorporate new technologies such as

drones during MONUC/MONUSCO

and to what extent did the UN contract

PMSCs for that purpose?

Official UN

documents,

academic literature, UN

website MONUSCO,

policy papers.

Resource

dependence

Situation of dependence

on someone else’s

resources, because of lack

of own resources.

1. What material and/or immaterial

military and security resources did

contracted PMSCs provide to the UN

and to what extent did the UN lack

those material and/or immaterial

military and security resources during

MONUC/MONUSCO?

Official UN

documents,

academic literature, UN

website MONUSCO,

policy papers, PMSCs

documents.

Cost-efficiency Situation in which the

benefits (outputs) are

larger than the material

costs (inputs).

1. What were MONUC/MONUSCO’s

expenditures and to what extent was the

UN confronted with budget-saving

pressures during

MONUC/MONUSCO?

2. To what extent did the contracted

PMSCs provide benefits (outputs) such

as functional specialisation to the UN

during MONUC/MONUSCO?

3. What were the material costs (inputs)

of the contracted PMSCs during

MONUC/MONUSCO?

Official UN

documents,

academic literature, UN

website MONUSCO,

Page - 31 - of 81

Political-instrumentalist

model (reduction

of political costs)

Depoliticisation

by delegation

Situation in which the

principal aims for

reducing political costs

and diffuse accountability

and transparency by

delegating tasks to

contracted agents.

1. To what extent did the UN apply

democratic oversight and control

mechanisms to contracted PMSCs

during MONUC/MONUSCO?

2. To what extent did the UN cover or

downplay its role and responsibility by

contracting contracted PMSCs during

MONUC/MONUSCO?

Official UN

documents,

academic literature, UN

website MONUSCO,

policy papers.

Ideationist model

(transnational

norms and ideas

defining the role

of state and

non-state actors) Laissez-faire (neo)liberal conception Privatization-friendly conception that

peacekeeping is not a

priori confined to the

state but may include

multiple (private) actors.

1. Can the UN approach to

peacekeeping during

MONUC/MONUSCO be identified as a

laissez-faire (neo) liberal conception?

a. To what extent did the UN

included multiple (private)

actors for peacekeeping during

MONUC/MONUSCO?

b. To what extent did the UN

actively try to find

market-based solutions for

peacekeeping during

MONUC/MONUSCO?

Official UN

documents, interviews

with UN officials,

academic literature, policy papers. State-interventionist conception Privatization-reluctant conception that

peacekeeping is confined

to the state.

Opposite of laissez-faire

(neo)liberal conception.

1. Can the UN approach to

peacekeeping during

MONUC/MONUSCO be identified as a

state-interventionist conception?

a. To what extent did the UN

demonstrate reluctance

towards the private military

and industry during

MONUC/MONUSCO?

b. To what extent did the UN

contribute its own strength and

capacity to

MONUC/MONUSCO?

3.6 Validity and Reliability

Page - 32 - of 81

research uses a set of theoretical models and their operationalized factors to explain the causes of privatization of peacekeeping within one case, only those factors will be taken into account when measuring the relationship between the theoretical models and the privatization of peacekeeping. The goal of this study is not to include all possible causes for the privatization within the case, but to test which theoretical model on the privatization of security has the highest explanatory value. Hence, the strict set of operationalized factors per theoretical model structured the data collection, and functioned as a focused research frame to measure the explanatory value of the theoretical models in the collected data.

A pitfall of a case-study is that it can have a limited external validity. That is, the results of a case-study are not necessarily generalizable to other contexts and a generalized conclusion is difficult to achieve (Tellis, 1997; Yin, 2003). This criticism is drawn because case study results are not quite applicable to a wider context in real life. A case study uses a small sample of cases from a larger universe of cases, a small sample is not directly generalizable to all the cases in the universe (Yin, 2003; Tellis, 1997). However, the aim of this research is not to generalize but to explain a complex issue by testing three theorical models and their explanatory value.A case study design is chosen because, given the complexity of the issue, it provides a lot of knowledge to assess one issue in depth. Due to the fact that the UN has involved PMSCs in a distinguishing number of regions and the differences between the regions, generalization to all the cases in the universe is not directly possible. Every single UN peacekeeping mission is unique and therefore different factors could lead to privatization of that specific mission. Hence, this research is not aimed to generalize the results to other cases but to provide contextualized in-depth insight into a phenomenon within one specific case. However, that does not mean that the actions and regulations of the UN used in this specific peacekeeping mission could not reflect the current UN policy on outsourcing to private actors.

Page - 33 - of 81

Part 4: Analysis

Chapter 1: Context of the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo and its peacekeeping mission MONUC/MONUSCO

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is one of the poorest countries in the Great Lakes Region, located in the center of Africa. The DRC’s recent history has been filled with instability, crises, regime changes and civil war (De Goede, 2008). An important factor for violence and conflict in the country are the DRC’s natural resources, with an estimated value of 24 Trillion USD. The DRC produces 50% of the world’s cobalt and has the second biggest copper reserves in the world. Hence, the involvement of all armed groups in the illegal exploitation of those natural resources, in the form of taxation, forced labour, and smuggling, is a serious problem in the DRC (UN Strategic Communications & Public Information Division, 2018).

The first Congolese War (1996-1997) in the DRC, named Zaïre at that time, started in 1996 and provoked one of the most challenging conflicts of its time. The cause of the war can be leaded back to the Rwandan genocide in 1994, which resulted in a movement of millions of refugees to the eastern Kivu regions of DRC. Subsequently, the movement and spillover of the Rwandan genocide caused a security crisis in Zaïre due to the formation of various armed groups in the east (Marks, 2007; UN.org., 2018a). In 1996, a rebellion by the Alliance des forces democratiques pour la liberation du Congo-Zaïre (AFDL) and its leader Laurent-Désiré Kabila against the army of President Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaïre, began in this area. This conflict resulted in the deposition of dictator Mobutu Sese Seko and the renaming of Zaïre in the Democratic Republic of Congo by the ADFL (Marks, 2007). Soon after the First Congo War, the Second Congo War (or Great African War) began in 1998 and lasted until 2003. This enormous conflict was triggered by the total collapse of the Zairian state and spread to eight other African countries and included various rebel groups (Marks, 2007). On the one hand, the rebels were supported by Rwanda and Uganda and on the other hand, Angola, Chad, Namibia and Zimbabwe supported President Kabila with military services (UN.org., 2018a). The First

Page - 34 - of 81

The first steps of UN peacekeeping operation MONUC were made by 1999. This phase is also referred to as the pre-transition phase of MONUC (1999-2003) (Reynaert, 2011). MONUC began as a traditional peacekeeping mission to observe and monitor the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement (Marks, 2007; Reynaert, 2011). This agreement, which was focused on ceasefire and disengagement of forces, was made in July 1999 between the DRC and the five regional states Angola, Namibia, Rwanda, Uganda and Zimbabwe (UN.org., 2018a). MONUC steadily grew and changed its mandate chapter from VI to VII, making it a more ‘robust’ peacekeeping mission (De Goede, 2008). In a series of resolutions that followed, the mandate of MONUC was expended into the supervision of the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement and assigned connected tasks (UN.org., 2018a). These mandate chapters are established in the UN Charter and give the UN Security Council the responsibility and ability to adopt a range of measures within the mandate chapters (UN.org., 2018b).

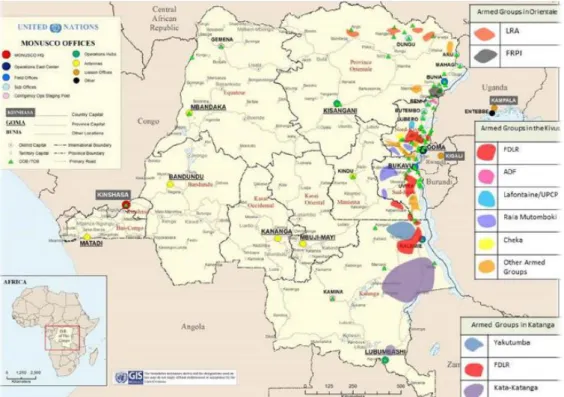

Officially the Second Congo War ended in April 2003, by signing the Sun City Agreements which were initiated by the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement, and the settlement of a transitional government (Reynaert, 2011; UN.org.2018a). Nonetheless, the conflict in the eastern part of the DRC continued between de various armed groups that are demonstrated in Figure 4

hereunder:

Page - 35 - of 81

Hence, MONUC continued with the transition phase (2003-2007) and later on with the post-transition phase (2007-2010). At the beginning of the post-transition phase from 2003, MONUC succeeded in the formation of a transitional government. In the transition phase, MONUC’s strategy shifted towards a more proactive attitude due to the approaching elections in 2006, which would be the first democratic elections since 1965 (Reynaert, 2011). Hence, the Security Council gave authorization to use “all necessary means, within its capabilities and in the areas

where its armed units are deployed, to deter any attempt at the use of force to threaten the political process (UN Security Council, 2005, March 31). This proactive transition phase of MONUC ended in 2006, after the presidential elections. The post-transition phase (2007-2010) ushered a less proactive phase of the mission. Since 2007, a legitimate elected government is established and DRC can be considered a sovereign state (Reynaert, 2011). In the years that followed, MONUC continuously increased its personnel and focused mainly on civilian protection, protection of institutions and government officials, and disarmament of foreign combatants (Dagne, 2011).

Page - 36 - of 81

Chapter 2: Analysis of the functionalist model

This chapter will discuss the functionalist model and its factors complexity, resource dependence and cost-efficiency. First of all, the factor complexity will be discussed by examining the nature of the MONUC/MONUSCO’s security situations, the missions’ incorporation of new technologies, and the use of PMSCs for those complex issues. Subsequently, paragraph 1.2 and 1.3 will discuss the factors resource dependence and cost-efficiency by looking into the exact tasks of contracted PMSCs and its costs and benefits. Finally, a summary of the functionalist model analysis will be given, including feedback from Kruck’s theory.

2.1 Complexity

2.1.1 Complexity of MONUC/MONUSCO

Since the creation of the mission in the DRC in 1999, it has been facing the challenges of jungle warfare and the lack of a responsible national military or government. Moreover, MONUC/MONUSCO was confronted with extremely difficult terrain and little local infrastructure in the DRC: “fewer than 500 km of paved roads in a territory (2.3 million km2) the size of Western Europe” (Dorn, 2011, p. 120). In the vast and difficult territory of the DRC, the mission had to carry out its mandate in a regional guerilla conflict of numerous national and foreign armed groups. What is notable for MONUC/MONUSCO as a peacekeeping mission, is that it is deployed to intercede, disarm and demobilize those violent groups, whereas most peacekeeping missions are deployed to keep peace after a conflict (Hultman, Kathman & Shannon, 2014). MONUC/MONUSCO was confronted with active conflict in a vast territory and faced serious human and material resource constraints (Reynaert, 2011). Moreover, the mission has faced dramatic humanitarian crises including the killing of hundreds of civilians and displacement of even more people (Cammaert, 2010). One of the mission’s biggest challenges was to deal with foreign armed groups in the conflict, such as the Rwandan Hutu Forces Démocratiques de Libération du Rwanda (FDLR). Since the government and army of

Page - 37 - of 81

through the years, caused by numerous violent non-state groups that grappled for power and resources, MONUC/MONUSCO was often confronted with unstable, unpredictable, and readily changing security situations including violent non-state actors in the DRC.

Apart from the political dimension, the conflict in the DRC also had an economical dimension which induced the continuation of the conflict. The various armed groups participating in the conflict took advantage of the mineral rich region in the eastern part of the DRC by exploiting and transporting the natural resources outside of the DRC and making profit from it. This eventually resulted in the continuation of the war because of the financial resources of the armed groups that helped finance it (Reynaert, 2011). Hence, due to the plentiful conflicting groups and their interests, it can be stated that “the conflict dynamics in the DRC are multi-layered” (Baaz & Verweijen, 2013, p. 564). Moreover, the unstable, unpredictable and readily changing security situations remained heavily present due to the many entrenched armed groups in the eastern part of the DRC, which activity level irregularly fluctuated (Coleman, 2017, July 10).

2.1.2 Technological changes during MONUC/MONUSCO

UN peacekeeping mission MONUC/MONUSCO is already operating for nineteen years. During those years, new technologies have changed warfare. Hence, UN peacekeeping operations continuously have to adapt and update their mandates concerning technology changes. Nonetheless, “UN peace operations have been slow to integrate these technologies in fulfilling their increasingly complex mandates” (Independent Commission on Multilateralism, 2016, p. 8). Despite the UN is still behind in using new technologies, “peacekeeping has, again and again, proven its willingness and capability to take on hard challenges, to define future capability needs, and to innovate in its missions” (Expert Panel on Technology and Innovation in UN Peacekeeping, 2015, p. 25).

Page - 38 - of 81

In September 2003, MONUC obtained observation and attack helicopter units which were delivered by the Indian Aviation Contingent, a contingent of the Indian Air Force. From there, the Mi-35 attack helicopters were of great value in the DRC and became “a powerful surveillance and weapons platform” (Dorn, 2011, p. 125). Amongst others, the helicopters were of great use in providing information to the peacekeepers about the location of rebel movements, deserted villages and fleeing civilians. Moreover, the helicopters were equipped with color television cameras and fourth-generation forward-looking infrared cameras (Dorn, 2011). Nonetheless, the helicopters were limited by poor weather conditions, communication difficulties, and too little fuel capacity (Dorn, 2011).

Hence, MONUC/MONUSCO’s efforts to improve its monitoring ability continued over the years. In January 2013, MONUSCO announced the plan to deploy UAVs for the purpose of surveillance in the Kivu provinces, located in the east of the DRC (Apuuli, 2014). The intention would be: “to improve our situational awareness and will I am sure will exert some deterrent

over all those people who move around with bad intentions in that particular area” (Ladsous, 2013, February 6, p. 4). However, MONUSCO’s request of UAVs can be dated back to 2008. The mission’s request was based on the capacity of UAVs to provide situation awareness about the rebel groups and their movements, convoy protection and further intelligence gathering (Blyth, 2013). This deployment of ‘eyes in the sky’ was opposed by some countries, such as Rwanda, arguing against the interference of foreign intelligence devices. Moreover, the introduction of UAVs was significant because they were never authorized before under any peacekeeping mandate (Blyth, 2013).

Page - 39 - of 81

Inasmuch MONUSCO’s mandate was also focused on protection of civilians, the deployment of an UAV was not solely aligned to force protection but also to improving the protection of civilians (Blyth, 2013). Hence, UAVs are “a modern response that can rapidly improve success and reaction rate of peacekeeping forces through surveillance” (Apuuli, 2014, p. 3). More importantly, the use of the UAV in MONUSCO is an adaptation that demonstrates the UN’s effort to adapt to the rapid technological changes in the world (Apuuli, 2014). MONUC/MONUSCO became the exemplification of a modern multidimensional peacekeeping operation which critically upgraded its field monitoring technology in the rapidly evolving and complex world of the 21st century (Dorn, 2011).

2.2 Resource dependence

Next to the factor complexity, the functionalist model puts forward the factor resource dependence. This paragraph will examine the factor resource dependence by looking into the provided resources of PMSCs to MONUC/MONUSCO and UN’s possible lack of those resources. The analysis of the PSMCs’ provided resources will also be of use in the following chapters of the analysis.

2.2.1 Provision of material and immaterial military and security resources by PMSCs

During the mission’s development, it has made extensive use of PMSCs. The analysis of UN procurement data demonstrates that both material and immaterial military and security resources are provided by contracted PMSCs during MONUC/MONUSCO. Hence, this analysis is demonstrated in Table 3 at the end of this paragraph, which provides an overview of all PMSCs that were contracted for MONUC/MONUSCO including an indication of their services and expenditures (the latter will be discussed more extensively in paragraph 1.3.3). It can be noticed from Table 3 that most of the resources that PMSCs provided to the mission are defined as security, safety and guard services by the UN. These services were provided during MONUC by local Congolese PMSCs named Human Dignity in the World, Magenya-protection & Gardiennage, KK Security Congo, and Delta Protection. Whereas Human Dignity in the World was only contracted for one year during MONUC, the other PSMCs provided their resources to the UN for several years. When MONUC was replaced by MONUSCO in 2010, the PMSCs Delta Protection, KK Security Congo, and Magenya-protection & Gardiennage

Page - 40 - of 81

Uganda in 2010 and both the Ugandan PMSC Askar Security Services Limited and German PMSC Top Sec International in 2012. However, these three PMSCs did not provide security and guard services in the DRC itself but were contracted to provide security services for the UN premises in Rwanda and Uganda in support of MONUSCO. Further, Societe Aigle Services LTD was contracted in 2012 to provide public order and security services in the DRC in support of the mission.

Alternatively to the PMSCs that provided security, safety and guard services, two companies were contracted for another category of services during the mission. The first is the so called American defense and government services contractor Pacific Architects and Engineers (PAE). This private company provided aerodrome operations services to MONUC from 2001 and onwards (Østensen, 2011). Although the data on the outsourcing to PAE during MONUC is limited, Table 3 demonstrates the PAE continued to providing its services to MONUSCO from 2012 until 2014. Further, another contract with a PMSC that deviates from the overall trend of outsourcing during the mission, is the UN’s agreement with Selex ES to provide of aerial surveillance and intelligence services in the form of an unmanned aerial system (e.g. drones). This material security and military service is provided by Selex ES and covered a contract for 3

years (2013-2016). Moreover, Selex ES did not only provide the unmanned aerial system consisting of unmanned and unarmed drones but also ground control stations, equipment, and logistics as stated by the website of key-player in aerospace, defense, and security Leonardo

from which Selex ES was a subsidiary at the time (2013, 11 September). Therefore, the provision of a drone by Selex ES and its complementary services can be placed clearly in both the categories of material- and immaterial security and military resources as the unmanned aerial system was provided with additional material and immaterial services.

Page - 41 - of 81

mission wide in the DRC (UN ACABQ, 2012, December 7). Further, Top Sec International was contracted for armed security services at 1 location in Kigali, Rwanda in 2012 (UN ACABQ, 2012, December 7).However, the remaining contracts give no indication whether the provided security and military services were armed or unarmed, making a complete picture of the proportions impossible.

Altogether, based on the analysis demonstrated in Table 3, it can be stated that most of the outsourcing of security and military services to the mission is done in the category of immaterial security resources, e.g. security, safety, and guarding services of UN key installations and personnel. However, two contracts with PSMCs deviated from the overall trend by providing logistical and transport services and aerial surveillance and intelligence services in both the categories of material and immaterial security and military resources. Further, when looking at the question to what extent the UN lacked those material and/or immaterial military and security resources provided by PMSCs during the mission, it can be clearly stated that the drones, delivered by Selex ES, were absent in UN’s own resources as the mission requested information gathering capabilities several times earlier in the mission. Eventually, the UN Procurement Division released a bid in order to find a provider for an unmanned aerial system in the private sector as it was the first time the UN officially deployed UAVs in its peacekeeping missions (Apuuli, 2014). Furthermore, it can be stated that the PMSCs performed selected tasks within the UN operation for which the UN lacked the capacity or the means (Østensen, 2013). Moreover, the guarding and security services were outsourced during the mission because the PMSCs could provide those services in a more effective, efficient or quick way than the UN itself (UN General Assembly, 2004, August 11).

Table 3: Overview of PMSCs contracted in MONUC/MONUSCO*

PMSC Services Mission Costs** Source

Pacific Architects and Engineers (PAE)

Aerodrome operations services in support of MONUC/MONUSCO MONUC 2001 and onwards (no specific contract information) 2012 2013-2014

Estimated on $ 34.2 million for one year contract 2001-2002, no available data on the costs in the following years of MONUC

2012 (total): $3,192,603 2012-2013: $2,510,996 2013: $1,255,498 2013-2014: $22,965,743 2014 (total): $6,690,737

Østensen (2011). Chatterjee (2004).