This study investigated school counselors’ perceptions about their involvement in nine school-family-com-munity (SFC) partnership programs and barriers to their involvement in such partnerships. A random sample of 72 school counselors in South Carolina pub-lic schools were asked to rate the importance and degree of their involvement related to nine SFC part-nerships. The study revealed that the participants per-ceived their involvement in SFC partnerships as very important and significant relationships were found between school counselors’ perceptions of importance of their involvement in partnerships and barriers to that involvement. Counselors varied in some of their per-ceptions and practices in the nine partnership pro-grams by school level (i.e., elementary, middle, high school).

S

chool-family-community (SFC) partnerships are collaborative initiatives or relationships that actively involve school personnel, parents, fami-lies, and community members and organizations as equal and mutual partners in the planning, coordi-nating, and implementing of programs and activities at home, at school, and in the community to help increase the academic, emotional, and social success of students (Davies, 1996; Epstein, 1992; Swap, 1993). This article describes a study that explored school counselors’ perceptions about their involve-ment in SFC partnerships.RELEVANT LITERATURE

In 1997, the United States Congress thought parent involvement and partnerships important enough to include them in a revised list of National Education Goals known as Goals 2000. This federal legislation called for the development of school partnerships with families and community groups. Goal 8 of the National Education Goals encouraged schools to promote “partnerships that will increase parental involvement and participation” by the year 2000 (U.S. Department of Education, 1997).

Many authors have suggested that SFC

partner-ships are one of the protective factors that foster educational resilience in at-risk children (Benard, 1995; Christenson & Sheridan, 2001; Epstein, 1995; Walsh, Howard, & Buckley, 1999). Educational reform over the past decade has even focused on school-community connections, home-school collaboration, or home-school-family-community partnerships as a means to helping youngsters achieve (Christenson & Conoley, 1992; Davies, 1991; Epstein, 1992; Merz & Furman, 1997; Ritchie, & Partin, 1994; Swap, 1992). These SFC partnerships have been evidenced through local gov-ernance models which include parents and commu-nity members in school governance, (e.g., site-based management); through parent and community involvement and volunteer programs (e.g., parents and community members as teacher-aides, mentors, and volunteers in the school); and through school-linked services (or interagency collaboration), which involve a number of approaches to linking social services agencies with schools in order to improve services to children (Merz & Furman).

An extensive review of the literature revealed that there are nine SFC partnership programs frequently found in schools. These nine partnership programs include:

1.Mentoring programs (Benard, 1995; Christiansen, 1997)

2.Parent centers (Comer, Haynes, Joyner, & Ben-Avie, 1996)

3.Family/community members as teachers’ aides (Epstein, 1995)

4.Parent and community volunteer programs (Gherke, 1998)

5.Home visit programs (Christiansen, 1997; Cole, Thomas, & Lee, 1988)

6.Parent education programs (Christiansen, 1997; Ritchie, & Partin, 1994)

7.School-business partnerships (Dedmond, 1991)

8.Parents and community members in site-based management (Walsh et al., 1999)

9.Tutoring programs (Merz & Furman, 1997).

Julia Bryan, Ph.D., is an assistant professor, Department of School Psychology and Counselor Education, The College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA. Cheryl Holcomb-McCoy, Ph.D.,is an assistant professor, Department of Counseling and Personnel Services, University of Maryland at College Park. E-mail: Jbryan@umd.edu, Ch193@umail.umd.edu

School Counselors’ Perceptions of

Their Involvement in

The emergence of SFC partnerships has also rede-fined the role of many school professionals, includ-ing school counselors (Adelman, 2002; Bemak, 2000; Taylor & Adelman, 2000). School counselors are being called on to take active roles in partner-ships and to be part of the efforts to find effective and innovative ways to develop them (Christiansen, 1997; Keys, Bemak, Carpenter, & King-Sears, 1998; Lockhart & Keys, 1998). Since school counselors are seen as having potential for leadership in educa-tional reform and as advocates of student success, it is suggested that school counselors promote educa-tional reform through leadership in partnerships between school, families, and communities (Bemak; Colbert, 1996; Dedmond, 1991; House & Hayes, 2002).

This study provides valuable information for counselor educators and school counseling profes-sionals as they focus more on SFC partnerships. In spite of the growing literature written about SFC partnerships and the prescribed roles for school counselors in SFC partnerships, no primary research could be found addressing the perceptions, roles, or involvement of the school counselor in relation to these SFC partnerships. In providing empirical data to address these questions, this study fills a gap in the research.

This study investigated school counselors’ percep-tions about their involvement in nine school-family-community partnership programs (e.g., mentoring, volunteer programs, tutoring, parent education) and barriers to their involvement in those partnerships. The primary research questions were as follows:

1.Overall, what are school counselors’ perceptions regarding school counselor involvement in SFC partnerships?

2.What are school counselors’ perceptions regard-ing school counselors playregard-ing a major role in nine types of SFC partnerships?

3.What are school counselors’ perceptions regard-ing the importance of nine types of SFC partner-ships in their schools?

4.What are school counselors’ perceptions regard-ing the importance of their role in nine types of SFC partnerships in their schools?

5.How willing are school counselors to be involved in nine types of SFC partnerships?

6.What barriers hinder school counselors’ involve-ment in SFC partnerships?

METHOD

ParticipantsA sample of 300 school counselors was randomly drawn from South Carolina’s State Department of Education’s complete listing of school counselors in

South Carolina’s public schools by stratified sam-pling. There were a total of 1,641 school counselors in South Carolina: 542 high school counselors, 714 elementary school counselors, and 385 middle or junior high counselors. To enable the strata or sub-groups to be compared and to ensure proportional representation, the researcher carried out propor-tional stratified sampling with sample sizes chosen so that the smallest was large enough to permit mean-ingful comparisons. Within each school level (ele-mentary, middle, and high), the number of coun-selors chosen was proportional to the representation of each of these subgroups within the entire state sample pool. The sample was stratified by randomly selecting 33% or 99 high school counselors, 44% or 132 elementary school counselors, and 23% or 69 middle or junior high school counselors.

There was a response rate of 25% with 75 surveys being returned. Only 72 or 24% were usable. Of the 72 participants, 86% were females and 12.5 % were male. The state director of guidance reported that this was representative of the school counselor pop-ulation in the state. Compared to the poppop-ulation of South Carolina’s school counselors, 37.5% of the respondents worked in elementary schools com-pared to 44% in the total population, 26.4% worked in middle schools compared to 23% in the total pop-ulation, and 26.4% worked in high schools com-pared to 33% in the total population.

Instrumentation

Survey development.No survey currently exists to assess school counselors’ perceptions about their partnership roles and practices. Therefore, a survey was designed (for additional information rgarding the survey’s design, please contct the authors). After a thorough review of the literature, a focus group with three school counselors and two counselor educators was implemented. The focus group met to discuss issues related to school counselors’ role in SFC partnerships. The survey was then constructed and piloted on ten master’s level and doctoral level counseling students who were currently school counselors. Feedback was given regarding question clarity, comprehensiveness, and acceptability. The pilot study confirmed that the survey had face and content validity. After revisions were made, the final draft of the survey was used for this study.

The final survey consists of four parts: the first part elicits demographic data; the second part con-cerns school counselors’ perceptions about the importance of SFC partnership programs in their schools and the importance of school counselor involvement in nine SFC partnership programs; the third part concerns school counselors’ perceptions of the degree to which six barriers hinder their involvement in partnerships and of their willingness

Counselors at all

school levels

perceived it as

important that

counselors should

play major roles in

partnerships.

to be involved in partnership programs; and the final part was a section for feedback so that counselors could offer any additional comments. Below is a description of the first three parts of the survey.

Demographic data. This section of the survey consists of ten items that obtained information about years of school counselor experience, gender, highest degree earned, accreditation of graduate school program, counselor’s ethnic background, school setting in which counselor works, type of school, community setting, percentage of students on free or reduced lunch, and percentages of each ethnic category of students. Years of experience was grouped into five categories: 1–5 years, 6–10 years, 11–15 years, 16–20 years, and over 20 years. School setting had three levels: elementary, middle or jun-ior high, and high school. Community type had three levels: urban, rural, and suburban.

Perceptions about the importance of counselor involvement in partnerships.The questions in this section of the survey asked participants to rate (1) the importance of school counselor involvement in partnerships, (2) the importance of counselors involvement in nine SFC partnership programs, (3) the importance of these nine SFC partnership pro-grams in their schools, and (4) the importance of their personal role in these nine SFC partnership programs. Question one, a measure of the overall importance of school counselor involvement in part-nerships, consisted of no sub-items. This question asked, “In your opinion how important is it that school counselors be involved in school-family-com-munity partnerships?” Questions two, three, and four each have nine sub-items related to the impor-tance of nine partnership programs. These sub-items were measured on a Likert scale from 1 to 5 with 1 = not important, 2 = rarely important, 3 = impor-tant, 4 = very imporimpor-tant, and 5 = exceptionally important. For example, question two asked, “In your opinion, how important is it that school coun-selors are involved in these SFC partnerships? (a) mentoring programs, (b) parent center, (c) fami-ly/community members as teachers’ aides, (d) vol-unteer program for family/community members, (e) home visitor programs, (f) parent education pro-grams, (g) school-business partnerships, (h) par-ent/family member on management teams/coun-cils, and (i) tutoring program.” Similarly, the sub-items were the same for questions three and four. Question three asked: In your opinion, how impor-tant are the following partnership activities in your school? Question four asked participants, “In your opinion, how important is your involvement in the SFC partnerships which exist in your school?

Perceptions about school counselors’ involve-ment in partnerships.Two of the questions in this sections asked participants to rate (a) the extent to

which six barriers hindered their involvement in school-family-community partnerships and (b) their willingness to be involved in nine partnership pro-grams. These questions were measured on a 5 point Likert scale with 1 = not at all, 2 = infrequently, 3 = frequently, 4 = very frequently, and 5 = all of the time. Question one had six sub-items each corre-sponding to a barrier that hindered school counselor involvement in school-family-community partner-ships. Counselors were asked to rate the degree of hindrance caused by each of the six barriers. For example, question one asked, “In your opinion, to what extent do these barriers keep you from being involved in school-family-community partnerships? (a) lack of time, (b) lack of opportunity, (c) too many counselor responsibilities, (d) lack of school policy, (e) inadequate training, (f) not consistent with school counselor’s role.”

Question two measured the extent to which school counselors are willing to be involved in nine partnership programs. This question asked: “In your opinion, to what extent are you willing to get involved in these types of partnerships?” Similar to questions two, three, and four in the previous sec-tion of the survey, the nine partnership programs made up the sub-items for question 2 in this section. This study indicated that the internal consistency or Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for the survey is .95 indicating satisfactory reliability.

Procedures

The survey was mailed to 300 (n = 300) school counselors in South Carolina along with a cover let-ter and a self-addressed stamped envelope. A defini-tion of school-family-community partnerships was provided along with directions for completion of the survey. In the cover letter, participants were informed of the anonymity, volunteer nature of the study, and that returning the completed survey indicated their consent. No follow-up was done due to lack of fund-ing. Seventy-two usable (24% return rate) surveys were returned. A power analysis revealed that this sample size resulted in a power of .70 and was suffi-cient to detect large effect sizes or differences or dif-ferences at the .05 level of significance.

DATA ANALYSIS

For the first part of survey, questions two through four, school counselors were compared across school level (between-subjects variable) and across nine partnership programs (within-subjects variable). The individual sub-items are the within-subject measures in the three split-plot analyses of variance (SPANO-VA) used to compare school counselors’ level of per-ceived importance for each of the nine partnership programs.

Elementary school

counselors

perceived the nine

school-family-community

partnerships to be

more important in

their schools than

did high school

counselors.

For the purpose of correlational analysis, the sub-items for each question were summed to provide total measures of importance. A Pearson’s correla-tion was performed on summed scales to determine if there is a significant correlation between percep-tions of the importance of counselor’s personal role in partnerships and perceived importance of part-nerships in the school.

Individual sub-items were the within-subject measures in the two split-plot analyses of variance (SPANOVA) used to examine mean differences in school counselors’ perceptions about barriers and their willingness to be involved in partnerships. School counselors were compared across school level (between-subjects variable) on each of the six barriers in question one and nine partnership pro-grams in question two.

Pearson’s correlations were conducted on summed scales of questions one and two along with the summed scale of question four in previous sec-tion of the survey. This was done to determine whether there is a significant inter-correlation between counselors’ perceptions of the degree of hindrance caused by barriers, perceptions of the importance of counselor’s personal role in ships, and perceptions of the importance of partner-ships in the school.

RESULTS

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and five split-plot analyses of variance (SPANOVA) were conducted to answer the questions concerning dif-ferences in school counselors’ perceptions of impor-tance and involvement by school level across nine partnership programs and six barriers. The Huynh-Feldt correction was used to determine the F-value for the within-subject variables. To examine signifi-cant main effects for school level, programs, and bar-riers, pairwise comparisons were conducted. Type I error was controlled for by using the Bonferroni method. No significant interaction effects were found for any of the SPANOVAs. Some Pearson’s correlations were also conducted to determine the relationship between counselors’ perceptions of the degree of hindrance caused by barriers, perceptions of the importance of counselor’s personal role in partnerships, and perceptions of the importance of partnerships in the school.

Research Questions Results

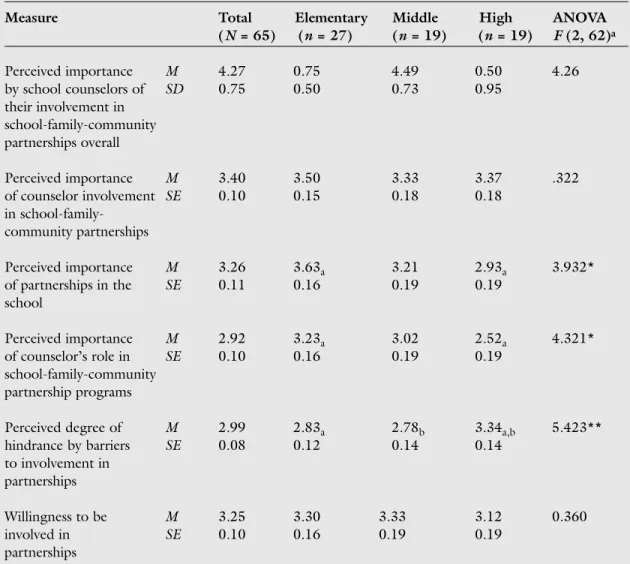

Overall, what are school counselors’ perceptions regarding school counselor involvement in SFC partnerships?Overall, the participants rated school counselor involvement as very important in school-family-community partnerships, M= 4.27, SD= .75, N = 72. A one-way ANOVA revealed that school

counselors did not vary by school level in their per-ceived importance of school counselor involvement in partnerships, F= 3.07, p= .054.

What are school counselors’ perceptions regarding school counselors playing a major role in nine SFC partnerships?School counselors did not differ by school level in the perceived impor-tance of school counselors playing major roles in the nine school-family community partnerships, F (2, 62) = .322, p = .726. Therefore, counselors at all school levels perceived it as important that coun-selors should play major roles in partnerships. The means and standard errors for the between-subjects variable and school level are found in Table 1.

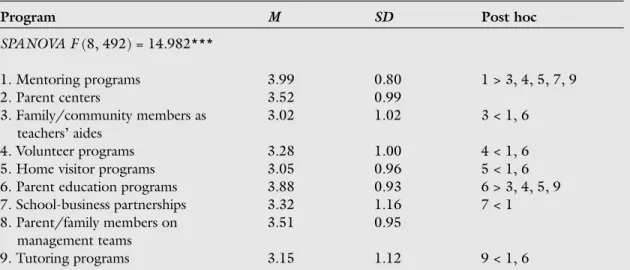

However, there were significant differences in per-ceived importance of school counselor involvement among the nine partnership programs, F(8,492) = 14.982, p = .000. Means, standard deviations and results of post hoc comparisons for the nine partner-ship programs are given in Table 2.

What are school counselors’ perceptions re-garding the importance of nine SFC partnerships in their schools?School counselors differed signifi-cantly by school level in their perceptions of the importance of partnerships in their own school, F (2, 62) = 3.932, p= .025. Elementary school coun-selors perceived the nine school-family-community partnerships to be more important in their schools than did high school counselors (see Table 1). There was also a significant effect for program, F(8, 466) = 13.794, p = .000. Perceived importance of the nine partnership programs varied significantly. Table 3 presents the means, standard deviations, and results of the pairwise comparisons for each program.

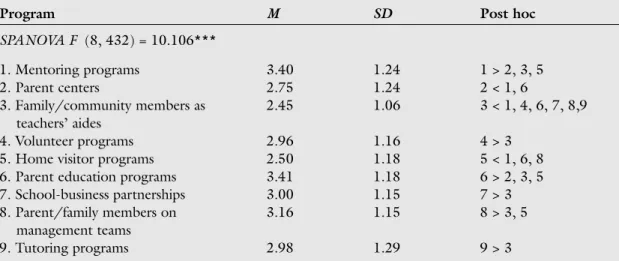

What are school counselors’ perceptions regarding the importance of their role in nine SFC partnerships in their schools?School coun-selors differed by school level in their perceptions of the importance of their role in school-family-com-munity partnerships, F(2, 62) = 4.321, p = .018. Elementary school counselors perceived their roles to be more important than high school counselors (see Table 1). There was also a significant effect for program (see Table 4). Counselors differed in the perceived importance of their role across the nine partnership programs.

As a post hoc analysis, the relationship between school counselors’ perceived importance of their role in the nine partnership programs and their per-ceived importance of the nine partnership programs in their schools was explored. The results indicated that there was a significant positive correlation between these two variables, r(72) = .752, p< .001.

How willing are school counselors to be involved in nine SFC partnerships?There were no significant differences by school level in willingness to be involved in partnerships (see Table 1).

School counselors

across all school

levels reported that

too many counselor

responsibilities and

lack of time most

frequently

hindered their

involvement in

school-family-community

partnerships.

However, there was a significant within-subjects effect for program, F(8, 419) = 11.810, p= .000. Table 5 presents the means and standard deviations by program type and the results of the post hoc comparison of means.

What barriers hinder school counselors’ involvement in SFC partnerships?There were sig-nificant differences found by school level in relation to school counselors’ perceptions about the barriers that hinder their involvement in school-family-com-munity partnerships, F (2, 62) = 5.423, p= .007. High school counselors perceived a significantly higher level of barriers than either middle school counselors or elementary school counselors (see Table 1).There were significant differences in the

perceptions of the degree to which the six barriers hindered involvement in partnerships, F(5, 299) = 67.573, p=.000. School counselors across all school levels reported that too many counselor responsibil-ities and lack of time most frequently hindered their involvement in school-family-community partner-ships. Means and standard deviations and results of pairwise comparisons using the Bonferroni approach are reported in Table 5.

DISCUSSION

There are a number of limitations that one must pay attention to in interpreting the results of this study. The self-report nature of this study may be

influ-Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, Standard Errors and Analysis of Variance Results of Between-Subjects Effect for School Level on Eight Dependent Measures

Measure Total Elementary Middle High ANOVA

(N= 65) (n= 27) (n= 19) (n= 19) F(2, 62)a Perceived importance M 4.27 0.75 4.49 0.50 4.26 by school counselors of SD 0.75 0.50 0.73 0.95 their involvement in school-family-community partnerships overall Perceived importance M 3.40 3.50 3.33 3.37 .322 of counselor involvement SE 0.10 0.15 0.18 0.18 in school-family-community partnerships Perceived importance M 3.26 3.63a 3.21 2.93a 3.932* of partnerships in the SE 0.11 0.16 0.19 0.19 school Perceived importance M 2.92 3.23a 3.02 2.52a 4.321* of counselor’s role in SE 0.10 0.16 0.19 0.19 school-family-community partnership programs

Perceived degree of M 2.99 2.83a 2.78b 3.34a,b 5.423**

hindrance by barriers SE 0.08 0.12 0.14 0.14 to involvement in partnerships Willingness to be M 3.25 3.30 3.33 3.12 0.360 involved in SE 0.10 0.16 0.19 0.19 partnerships

Note.Means in a row sharing subscripts are significantly different. For all measures, higher means indicate high-er scores.

aThis is the Fstatistic for the between-subject variable in the split-plot analysis of variance (SPANOVA)

con-ducted for each measure. Results for the within-subject effects are presented in other tables. *** p< .001. ** p< .01. *p< .05.

enced by response bias caused by counselors want-ing to appear competent and to be seen as engagwant-ing in professionally desirable behavior related to school-family-community partnerships. Response style and honesty of the respondents will affect the validity of the information received to some extent. Another limitation is that the participants in the study came from the state of South Carolina only. This limits the generalizability of the findings since results may be representative of the perspectives of school

coun-selors in South Carolina only. Attempts to generalize results further a field should be done with caution since one cannot assume that the sample in this study is representative of other populations outside of South Carolina. In addition, non-response bias may have resulted from the extremely low return rate of 24%. It is possible that only school counselors with school-family-community partnership programs in their schools may have responded to the survey.

Nevertheless, this study is the first attempt to

pro-Table 2. Means, Standard Deviations and SPANOVA Results for Within-Subjects Effect of Importance Ratings of Counselor Involvement in Nine Partnership Programs

Program M SD Post hoc

SPANOVA F(8, 492) = 14.982*** 1. Mentoring programs 3.99 0.80 1 > 3, 4, 5, 7, 9 2. Parent centers 3.52 0.99 3. Family/community members as 3.02 1.02 3 < 1, 6 teachers’ aides 4. Volunteer programs 3.28 1.00 4 < 1, 6

5. Home visitor programs 3.05 0.96 5 < 1, 6 6. Parent education programs 3.88 0.93 6 > 3, 4, 5, 9 7. School-business partnerships 3.32 1.16 7 < 1 8. Parent/family members on 3.51 0.95

management teams

9. Tutoring programs 3.15 1.12 9 < 1, 6

Note.A SPANOVAwas conducted with school level as the between-subjects variable and program as the with-in-subjects variable. The results of the within-subject effect are presented here. Adjustments were made for mul-tiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method. The level of significance used was p= .001.

Table 3. Means, Standard Deviations and Split-plot ANOVA Results for Within-Subjects Effect of Importance Ratings of Nine Partnership Programs in the School

Program M SD Post hoc

SPANOVA F (8, 466) = 13.794*** 1. Mentoring programs 3.54 1.24 1 > 3, 5 . 2. Parent centers 94 1.38 2 < 6, 7, 9 3. Family/community members as 2.84 1.13 3 < 1, 6, 7, 8, 9 teachers’ aides 4. Volunteer programs 3.32 1.21

5. Home visitor programs 2.72 1.16 5 < 1, 6, 7, 8, 9 6. Parent education programs 3.51 1.09 6 > 2, 3, 5 7. School-business partnerships 3.64 1.12 7 > 2, 3, 5 8. Parent/family members on 3.60 0.98 8 > 3, 5

management teams

9. Tutoring programs 3.60 1.09 9 > 2, 3, 5

Note.A SPANOVAwas conducted with school level as the between-subjects variable and program as the with-in-subjects variable. The results of the within-subject effect are presented here. Adjustments were made for mul-tiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method. The level of significance used was p= .001.

vide empirical data to address questions regarding the perspectives and practices of school counselors regarding school-family-community partnerships. Therefore, it will provide a basis for future research on the topic. This study revealed that school coun-selors regardless of school level consider it very important that they be involved in school-family-community partnerships and that they play major roles in such partnerships. On the other hand, ele-mentary school counselors perceive partnership pro-grams as being more important in their schools than

high school counselors and perceive their present roles in school-family-community partnerships as more important than high school counselors. Additionally, school counselors perceive the impor-tance of their roles in some partnership programs as more important than in others. Overall, the highest mean levels of importance were attributed to men-toring and parent education programs regardless of counselor’s work setting.

School counselors also differ by school level in their perceptions of hindrance caused by barriers to

Table 4. Means, Standard Deviations and Split-plot ANOVA Results for Within-Subjects Effect of Importance Ratings of Counselor’s Personal Role in Nine Partnership Programs

Program M SD Post hoc

SPANOVA F (8, 432) = 10.106*** 1. Mentoring programs 3.40 1.24 1 > 2, 3, 5 2. Parent centers 2.75 1.24 2 < 1, 6 3. Family/community members as 2.45 1.06 3 < 1, 4, 6, 7, 8,9 teachers’ aides 4. Volunteer programs 2.96 1.16 4 > 3

5. Home visitor programs 2.50 1.18 5 < 1, 6, 8 6. Parent education programs 3.41 1.18 6 > 2, 3, 5 7. School-business partnerships 3.00 1.15 7 > 3 8. Parent/family members on 3.16 1.15 8 > 3, 5

management teams

9. Tutoring programs 2.98 1.29 9 > 3

Note.A SPANOVAwas conducted with school level as the between-subjects variable and program as the with-in-subjects variable. The results of the within-subject effect are presented here. Adjustments were made for mul-tiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method. The level of significance used was p= .001.

Table 5. Means, Standard Deviations and Split-plot ANOVA Results for Within-Subjects Effect of Degree of Willingness to be Involved in Nine Partnership Programs

Program M SD Post hoc

SPANOVA F(8, 419) = 11.810*** 1. Mentoring programs 3.75 1.00 1 >3, 5 2. Parent centers 3.34 1.06 2 > 6 3. Family/community members as 2.57 1.16 3 < 1, 2, 4, 6, 8 teachers’ aides 4. Volunteer programs 3.15 1.13 4 < 3

5. Home visitor programs 3.00 1.24 5 < 1, 6 6. Parent education programs 3.80 0.99 6 > 3, 5 7. School-business partnerships 3.17 1.24

8. Parent/family members on 3.32 1.16 8 > 3 management teams

9. Tutoring programs 3.22 1.29

Note.A SPANOVAwas conducted with school level as the between-subjects variable and program as the within-subjects variable. The results of the within-subject effect are presented here. Adjustments were made for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method. The level of significance used was p= .001.

their involvement. High school counselors perceive a higher level of hindrance than both elementary and middle school counselors. However, counselors at all levels perceive too many counselor responsibilities and lack of time as being major hindrances to their involvement in school-family-community partner-ships. On average, school counselors at every school level were frequently willing to be involved in part-nership programs. However, they were more willing to be involved in some types of programs than oth-ers. They expressed the highest mean levels of will-ingness to be involved in parent education and men-toring programs.

It is valuable to know that school counselors believe their involvement in school-family-commu-nity partnerships to be very important given the focus on school-family-community partnerships in educational reform (Colbert, 1996; Holcomb-McCoy, 2001). Since school counselors are being called on to play major roles in school-family-com-munity partnerships, it is important that they endorse these partnerships as their perceptions will likely influence their behavior.

The finding that elementary school counselors perceive their personal roles in partnership programs as more important than middle or high school coun-selors is supported by previous research. Teachers and school psychologists in elementary schools have been found to have higher levels of involvement in school-family-community partnership activities (Epstein & Dauber, 1991; Pelco, Ries, Jacobson, & Melka, 2000). While overall there is more parent involvement in elementary schools, research studies have highlighted the importance of school-family-community partnerships in meeting the develop-mental needs of students at the middle and high school levels (Epstein & Sanders, 2000).

Additionally, it is important to note that the

sig-nificant relationship between the perceived impor-tance of counselor’s personal role in the partnership programs and the perceived importance of these partnership programs in their school is also support-ed by prior research in which elementary school teachers reported stronger involvement of their schools in school-family-community partnerships (Epstein & Dauber, 1991). The higher level of importance accorded to their roles in partnerships by elementary school counselors when compared to high school counselors in this study may be because there is a higher level of involvement in these part-nerships at the elementary school level. The more their school is involved in partnerships, the more the counselor may be involved in partnership programs, thus viewing their roles in partnerships as more important. Thus, school counselor involvement in partnerships appears to be influenced by institution-al culture and parent involvement practices related to school-family-community partnerships.

Differences in reported levels of importance of counselors’ partnership roles among elementary and high school counselors did not result from differ-ences in perceived importance of counselor involve-ment in partnerships. School counselors across all levels consider counselor involvement in partnership programs to be important. Additionally, it is clear that high school counselors in this study are equally willing to be involved in partnership programs when compared to elementary and middle school coun-selors. It is noteworthy that high school counselors perceive a higher level of barriers to their involve-ment in partnerships than eleinvolve-mentary school coun-selors. It is also notable that counselors who perceive partnerships to be less important in their schools and perceive their role in partnerships as less important, also perceive a higher degree of barriers to their involvement in school-family-community

partner-Table 6. Means, Standard Deviations and Split-plot ANOVA Results for Within-Subjects Effect of Degree of Hindrance Caused by Six Barriers to Counselor Involvement in Partnerships

Barrier M SD Post hoc

SPANOVA F(5, 299) = 67.573***

1. Lack of time 3.98 0.84 1 > 2, 4, 5, 6

2. Lack of opportunity 2.67 1.09 2 < 1, 3

3. Too many counselor responsibilities 4.26 0.82 3 > 2, 4, 5, 6 4. Lack of school policy 2.49 1.22 4 < 1, 3

5. Inadequate training 2.05 1.02 5 < 1, 3

6. Not consistent with school 2.33 1.12 6 < 1, 3 counselor’s role

Note.A SPANOVAwas conducted with school level as the between-subjects variable and program as the with-in-subjects variable. The results of the within-subject effect are presented here. Adjustments were made for mul-tiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method. The level of significance used was p= .002.

ships. One reason that high school counselors may accord less importance to their roles in partnership programs is that they may be too overwhelmed by their administrative and clerical duties to become involved in partnerships to the extent that they think school counselors should.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOL

COUNSELORS AND FURTHER RESEARCH

Given the barriers that school counselors face to their involvement in partnership programs, it is not enough simply to train counselors in how to build partnerships. Rather, in order to increase school counselor involvement in school-family-community partnerships, school counselor education programs will need to also train counselors to advocate for partnership programs, to devise strategies to over-come barriers, and to be catalyst for change in the school system. This means that counselors will have to be more proactive in defining their roles in the school. This is important since the school’s culture related to partnerships appears to influence coun-selors’ perceptions of the importance of their roles in these partnerships. Counselors must be trained to be proactive in defining their own roles within the insti-tutions so that they are not forced to abnegate important functions such as collaboration in school-family-community partnerships.Regarding further research in this area, it would be important to replicate this study with a national representative study and a larger sample size to determine if the differences and relationships found in this study still hold. Qualitative research is need-ed to do an in-depth study of attitudes, beliefs, events, and policies that influence school counselor involvement in school-family-community partner-ships. Such a study would provide valuable informa-tion for operainforma-tionalizing measures that appear to influence school counselor involvement in partner-ships. These measures may then be used to further investigate the relationships between perceptions, training, and practice found in this study and to determine the factors that influence school coun-selor collaboration in school-family-community partnerships. ❚

References

Adelman, H. S. (2002). School counselors and school reform: New directions.Professional School Counseling ,5,

235–248.

Bemak, F. (2000). Transforming the role of the counselor to provide leadership in educational reform through collab-oration.Professional School Counseling, 3,323–331. Benard, B. (1995).Fostering resilience in children.Urbana, IL: ERIC

Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED386327).

Christenson, S. L., & Conoley, J. C. (Eds.). (1992).Home-school collaboration: Enhancing children’s academic and social competence.Silver Spring, Maryland: National Association of School Psychologists.

Christenson, S. L., & Sheridan, S. M. (2001).Schools and families: Creating essential connections for learning.New York: The Guilford.

Christiansen, J. (1997). Helping teachers meet the needs of stu-dents at risk for school failure.Elementary School Guidance and Counseling, 31,204–210.

Colbert, R. D. (1996). The counselor’s role in advancing school and family partnerships.The School Counselor, 44,

100–104.

Cole, S. M., Thomas, A. R., & Lee, C. C. (1988). School counselor and school psychologist: Partners in minority family out-reach.Journal of Multicultural Counseling and

Development, 16,110–116.

Comer, J. P., Haynes, N. M., Joyner, E. T., & Ben-Avie, M. (Eds.). (1996).Rallying the whole village: The Comer process for reforming education.New York: Teachers College. Davies, D. (1991). Schools reaching out: Family, school, and

community partnerships for student success.Phi Delta Kappan, 72,376–382.

Davies, D. (1996).Partnerships for student success: What we have learned about policies to increase student achievement through school partnerships with families and communi-ties.Baltimore: Center on Families, Communities, Schools and Children’s Learning. John Hopkins University. Dedmond, R. M. (1991). Establishing, coordinating

school-com-munity partnerships.NASSP Bulletin, 75(534), 28–35. Epstein, J. L. (1992). School and family partnerships: Leadership

roles for school psychologists. In S. L. Christenson, & J. C. Conoley (Eds.),Home-school collaboration: Enhancing chil-dren’s academic and social competence (pp. 19–52). Colesville, MD: National Association of School Psychologists.

Epstein, J. L. (1995). School/family/community partnerships: Caring for the children we share.Phi Delta Kappan, 76,

701–712.

Epstein, J. L., & Dauber, S. L. (1991). School programs and teach-ers practices of parent involvement in inner-city elemen-tary and middle schools.The Elementary School Journal, 91,289–305.

Epstein, J. L., & Sanders, M. G. (2000). Connecting home, school and community: New directions for social research. In M. Hallinan (Ed.),Handbook of sociology of education.New York: Plenum.

Gherke, M. E. (1998). Home, school, community partnerships. In J. M. Allen (Ed.),School counseling: New perspectives and practices(pp. 121–125). Greensboro, NC: ERIC Clearinghouse on Counseling and Student Services. Holcomb-McCoy, C. (2001).Examining urban school counseling

professionals’ perceptions of school restructuring activities.

(ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED452451). House, R. M., & Hayes, R. L. (2002). School counselors: Becoming

key players in school reform.Professional School Counseling, 5,249–256.

Keys, S., & Bemak, F., Carpenter, S. L., & King-Sears, M. E. (1998). Collaborative consultant: A new role for counselors serv-ing at-risk youths. Journal of Counseling and

Development, 76,123–134.

Lockhart, E. J., & Keys, S. G. (1998). The mental health counsel-ing role of school counselors.Professional School Counseling, 1(4), 3–6.

Merz, C., & Furman, G. (1997).Community and schools: Promise and paradox.New York: Teachers College.

The highest mean

levels of

importance were

attributed to

mentoring and

parent education

programs

regardless of

counselor’s work

setting.

Pelco, L. E., Ries, R. R., Jacobson, L., & Melka, S. (2000).

Perspectives and practices in family-school partnerships: A national survey of school psychologists.School Psychology Review, 29,235–250.

Ritchie, M. H., & Partin, R. L. (1994). Parent education and con-sultation activities of school counselors.The School Counselor, 41,165–170.

Swap, S. M. (1992). Parent involvement and success for all chil-dren: What we know now. In S. L. Christenson, & J. C. Conoley (Eds.),Home-school collaboration: Enhancing chil-dren’s academic and social competence(pp. 19–52). Colesville, MD: National Association of School Psychologists.

Swap, S. (1993).Developing home-school partnerships.New York: Teacher’s College.

Taylor, L., & Adelman, H. S. (2000). Connecting schools, families, and communities.Professional School Counseling, 3,

298–307.

U. S. Department of Education. (1997).Achieving the goals. Goal 8: Parent involvement and participation.Washington, DC: Author.

Walsh, M. E., Howard, K. A., & Buckley, M. A. (1999). School coun-selors in school-community partnerships: Opportunities and challenges.Professional School Counseling, 2,