RESIDENTIAL MOBILITY DESIRES AND BEHAVIOUR

OVER THE LIFE COURSE : LINKING LIVES THROUGH

TIME

Rory Coulter

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD

at the

University of St Andrews

2013

Full metadata for this thesis is available in

St Andrews Research Repository

at:

http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/

Please use this identifier to cite or link to this thesis:

http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3476

This item is protected by original copyright

Residential mobility desires and behaviour over

the life course: Linking lives through time

Rory Coulter

This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD

at the University of St Andrews

Declarations

1. Candidate’s declarations:

I, Rory Coulter, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 69,500 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree.

I was admitted as a research student in September, 2009 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September, 2009; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2009 and 2012.

Date: signature of candidate:

2. Supervisor’s declaration:

I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree.

Date: signature of supervisor:

3. Permission for electronic publication:

The following is an agreed request by candidate and supervisor regarding the electronic publication of this thesis:

(ii) Access to all of printed copy but embargo of all of electronic publication of thesis for a period of five years on the following grounds:

publication would preclude future publication publication would be in breach of law or ethics

Date: signature of candidate:

Abstract

As residential mobility recursively links individual life courses and the characteristics of places, it is unsurprising that geographers have long sought to understand how people make moving decisions. However, much of our knowledge of residential mobility processes derives from cross-sectional analyses of either mobility decision-making or moving events. Comparatively few studies have linked these separate literatures by analysing how residential (im)mobility decisions unfold over time within particular biographical, household and spatio-temporal contexts. This is problematic, as life course theories suggest that people frequently do not act in accordance with their underlying moving desires. To evaluate the extent to which residential (im)mobility is volitional or the product of constraints therefore requires a longitudinal approach linking moving desires to subsequent moving behaviour.

Acknowledgements

I always love reading the acknowledgements section of texts and I’ve been eagerly looking forward to writing my own since starting this project three years ago. Now that it is time to do so, I’ve become aware that avoiding the trap of simply reeling off an enormous list of names is much more difficult than I had anticipated. This is because I am only now coming to realise how deeply indebted I am to others for the help and support I have received since 2009.

I’d like to start by thanking Maarten for all his encouragement, advice and support over the last few years. Without him, it’s extraordinarily unlikely I would have even started this project, let alone seen it through to what I hope is a successful conclusion. I have benefited hugely from Maarten’s supervision in numerous ways, ranging from his willingness to share methodological advice through to his extensive experience with the dark arts of academic publishing. I am particularly grateful for how much interest he has always shown in my work and how much time he has always had for my project, even after leaving St Andrews for Delft. In my experience, few people can match Maarten’s email response times! In the early days of my project, I also benefited greatly from the supervision provided by Peteke and Paul. Their comments on my initial ideas and draft chapters helped give my work the focus and rigour required in a doctoral thesis. I am also heavily indebted to Allan for taking over my supervision in 2011. His deep knowledge of theory and the migration literature has been invaluable and has taken me in challenging new directions. I would especially like to thank Allan for the thorough commentary he has always provided on my draft manuscripts. His attention to detail and encouragement to always look to the ‘big picture’ has improved my work immensely.

willing to help me out. On a more pragmatic note, both the School of Geography and Geosciences and CHR should also be thanked for funding my doctoral studies.

As geographers, we are of course always aware of the important roles ‘space’ and ‘place’ play in everyday life. From my perspective, it has been a pleasure to share office spaces with so many great colleagues at St Andrews. Sara, Susan and Mel, my longest serving cellmates in Room 601, deserve honourable mentions here for putting up with me for several years. Thanks to them and the hospitality of Dermot Goodwill, working in the Irvine Building has always been productive and enjoyable regardless of the air temperature. At CHR, Tom, Alice and David should be mentioned in despatches for their important contributions to both the academic and social side of life at the Observatory. Thanks are also due to everyone else at CHR for their friendship, encouragement and for turning my PhD into a gastronomic experience. It is well known that research students march on their stomachs, and there has never been a lack of (free!) lunches, cakes, biscuits and sweets at the Observatory to keep me going. I also have fond memories of many illustrious evening ‘Pat-downs’. On the calorie expenditure side, I’ve particularly enjoyed my many runs, hill walks, darts matches and games of tennis with various colleagues at CHR. Outwith St Andrews, thanks are of course also due to all my friends and family who’ve helped me to reach this point through their constant support.

Lastly, I’d like to conclude by acknowledging the debt I owe to the thousands of nameless BHPS participants, many of whom who have completed interviews each year since I was only four years old. Without their co-operation, none of this would have been possible.

Foreword

This thesis consists of a portfolio of four empirical research papers embedded within four critical discussion chapters. All of the four papers have been published or submitted to peer reviewed academic journals. Chapters four and five have already been published in Environment and Planning A and Population, Space and Place respectively. At the time of writing (February 2013), chapter six is forthcoming in Housing Studies, while chapter seven will soon be published in Environment and Planning A.

Disclaimer

Contents

Declarations I

Abstract III

Acknowledgements IV

Foreword VI

Disclaimer VII

Contents VIII

List of figures and tables XII

Figures XII

Tables XIII

Chapter 1. Introduction 1

1.1 Introduction 1

1.2 Linking mobility decision-making to actual moving behaviour 5 1.2.1 Adopting a longitudinal life course perspective 5 1.2.2 Linking moving desires and subsequent moving behaviour 8 1.3 Thesis objective and structure 12

Chapter 2. Conceptual framework 17 2.1 Analysing the geography of migration flows 18 2.1.1 Labour market perspectives 18 2.1.2 Non-labour market explanations 20 2.2 The value of disaggregate analysis 22 2.2.1 Understanding why people move 22 2.2.2 Analysing short distance moves 24 2.2.3 The importance of residential immobility 28 2.3 Why families move: Theorising residential mobility 30 2.3.1 Disequilibrium and residential mobility 30 2.3.2 Residential mobility and the family life cycle 33 2.3.3 Stress-threshold models: Place utility and residential

satisfaction

36

2.3.4.2 Contextual effects at the household scale 49 2.3.4.3 Macro contextual effects 53 2.4 The mobility decision-making process 56 2.4.1 Theorising the mobility decision-making process 58 2.4.2 The gradualist model of mobility decision-making 59 2.4.3 Decision-making as a response to sudden life events 65 2.5 Analysing mobility decision-making and actual moving behaviour:

Towards a longitudinal perspective

68

2.6 Research gaps and questions 70

2.6.1 Analysing the relations between moving desires, expectations and actual moving behaviour

71

2.6.2 Investigating the linked lives of partners 72 2.6.3 Exploring the biographical dimension of mobility decision-

making

74

2.6.4 Analysing desire abandonment and the duration of wishful thinking

76

Chapter 3. Research design 80

3.1 Philosophy and methods 81

3.1.1 The value of quantitative methods 81 3.1.2 Qualitative analysis: Studying emotions and identities 83 3.1.3 Towards a postpositivist quantitative analysis 85

3.2 Longitudinal approaches 86

3.2.1 Retrospective surveys 86 3.2.2 Prospective data collection 88 3.2.3 Using prospectively gathered secondary data 89 3.3 Introducing the British Household Panel Survey 91

Chapter 4. A longitudinal analysis of moving desires, expectations x

and actual moving behaviour

103

4.1 Introduction 104

4.2 Literature review 107

4.3 Data and methods 111

4.3.1 Dataset and selection 111

4.4 Analysis 115 4.4.1 Expressing moving desires and expectations 117 4.4.2 Moving desire-expectation combinations and subsequent

mobility

123

4.5 Conclusions 126

Chapter 5. Partner (dis)agreement on moving desires and the subsequent moving behaviour of couples

130

5.1 Introduction 131

5.2 Background 133

5.3 Data and methods 137

5.4 Results 141

5.4.1 The occurrence of disagreements 141 5.4.2 Desire disagreements and actual moving behaviour 146

5.5 Conclusions 151

Chapter 6. Following people through time: An analysis of individual residential mobility biographies

154

6.1 Introduction 155

6.2 Conceptual framework 157

6.2.1 Disequilibrium and the life course model 157 6.2.2 Residential mobility within a life course framework 159

6.3 Data and methods 162

6.3.1 Data and sample selection 162

6.3.2 Methods 164

6.4 Analysis 165

6.5 Conclusions 180

Chapter 7. Wishful thinking and the abandonment of moving desires over the life course

183

7.1 Introduction 184

7.2 Conceptual framework 186

7.3 Data and methods 191

7.4.1 Desire emergence 194 7.4.2 The duration and outcome of wishful spells 197

7.5 Conclusions 208

Chapter 8. Conclusions and discussion 211

8.1 Motivations and objective 211

8.2 Fulfilling the objective: Empirical summary 214 8.2.1 Analysing the relations between moving desires, expectations and actual moving behaviour

214

8.2.2 Investigating the linked lives of partners 215 8.2.3 Exploring the biographical dimension of mobility decision-

making

216

8.2.4 Analysing desire abandonment and the duration of wishful thinking

217

8.3 Broader insights and implications 218 8.3.1 Theoretical developments 219 8.3.2 Methodological insights 221

8.3.3 Policy relevance 222

8.4 Methodological reflections 223

8.4.1 Data constraints 224

8.5 Future directions and concluding remarks 226

8.5.1 Direct extensions 227

8.5.2 Linking mobility decision-making and social outcomes 230 8.5.3 Enhancing the biographical approach 231

8.5.4 Final remarks 231

References 233

List of figures and tables

Figures

Figure 1.1 Temporal and spatial dimensions of human mobility 2

Figure 1.2 Thesis structure 13

Figure 2.1 Stages in the family life cycle 34

Figure 2.2 Household transitions and changing housing needs 35

Figure 2.3 Speare’s model of the initial phase of mobility decision-

making

38

Figure 2.4 A diagrammatic example of a hypothetical life course 43

Figure 2.5 Residential mobility within a life course framework 44

Figure 2.6 Attitude-consistent and -discrepant moving behaviours 57

Figure 2.7 A conceptual model of the mobility decision-making process 61

Figure 3.1 BHPS sample tracking procedures and naming conventions 94

Figure 3.2 BHPS response rates and the reasons for the attrition of the 9,912 OSMs who completed a full interview in 1991

97

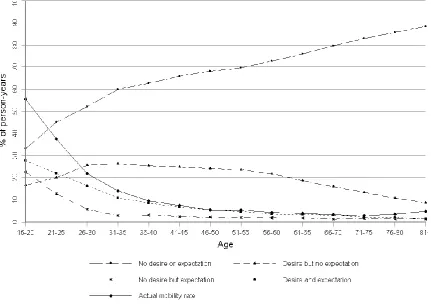

Figure 4.1 Moving desire-expectation combinations and actual moves by age

116

Figure 5.1 Partner (dis)agreement in moving desires by age 142

Figure 6.1 The mobility biographies of selected BHPS respondents 168

Figure 6.2 Mobility biographies subdivided by the age of the respondent in 1991

169

Figure 6.3a A typology of mobility biographies 172

Figure 6.3b A typology of mobility biographies continued 173

Figure 6.4 The likelihood of experiencing each sequence type by age in 1991

176

Figure 7.1 A conceptual model of the emergence, duration and outcome of wishful spells

Figure 7.2 The outcomes of wishful spells by age at the start of the spell

198

Tables

Table 2.1 The distance over which residential moves are made in Britain

25

Table 2.2 Recent demographic trends and their implications for life cycle models of housing careers

41

Table 2.3 The links between major life events, residential mobility, and the housing career

47

Table 3.1 Basic attributes of four major household panel surveys 92

Table 4.1 Variable summary statistics 113

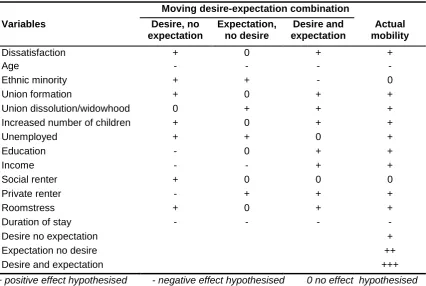

Table 4.2 Hypothesised variable effects on moving desire-expectation combinations and actual moves

115

Table 4.3 Bivariate analysis linking subjective evaluations of dwelling & neighbourhood to moving desire-expectation combinations

118

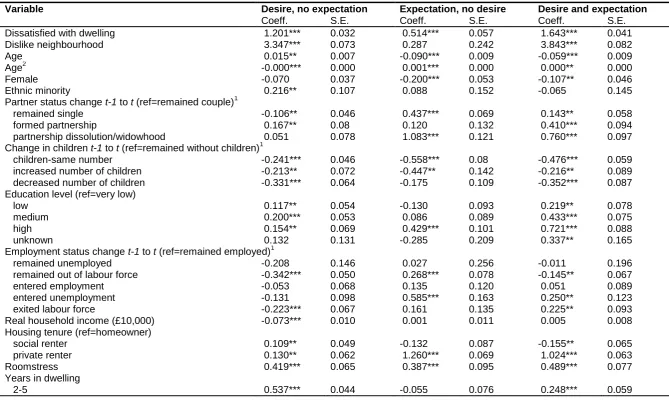

Table 4.4 Multinomial logit model of moving desire-expectation combinations

119

Table 4.5 Moving desire-expectation combinations and actual moving behaviour over the next year

124

Table 4.6 Panel logit models of the annual likelihood of moving 125

Table 5.1 Variable summary statistics 140

Table 5.2 Partner similarity and (dis)agreement on whether moving is desirable

143

Table 5.3 Shared commitments and (dis)agreement on whether moving is desirable

144

Table 5.4 Moving desires and the subsequent moving behaviour of couples

146

Table 5.5 Panel logistic regression models of the annual moving propensity of couples between t and t+1

148

Table 6.1 Combinations of moving desire and subsequent moving behaviour

Table 6.2 Moving desires and subsequent moving behaviour across two consecutive survey waves

166

Table 6.3 Sequence groupings and classification rules 171

Table 6.4 Variable summary statistics 177

Table 6.5 Six logit models estimating the likelihood of experiencing each sequence type

179

Table 7.1 Summary statistics for variables included in the fixed effects model

195

Table 7.2 Fixed effects logistic regression model of wishful thinking 196

Table 7.3 Life table describing the duration of wishful spells 200

Table 7.4 Summary statistics for variables included in the multinomial model

202

Table 7.5 Multinomial logistic discrete-time event history model of desire fulfilment and abandonment

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 Introduction

It has long been recognised that mobility has always been a fundamental feature of human societies. Yet over the last decade, social scientists have increasingly begun to position mobility as the defining characteristic of the twenty-first century world. Many scholars argue that today “all the world seems to be on the move” (Sheller and Urry, 2006: 207), as people, goods, capital, ideas, information and images are all becoming ever more mobile. Seizing upon Sheller and Urry’s proclamation that this heralds a ‘new mobilities paradigm’ for social research, a vibrant literature analysing a huge variety of forms of physical, virtual and cultural movement has developed (King, 2012). Geographers have been particularly active in this ‘mobilities turn’. This is because mobility and immobility are fundamentally geographical processes, which need to be analysed to better understand how people shape, and are shaped by, the contexts in which they live (Findlay and Li, 1999).

instance, some types of mobility do not easily fit into his temporal-permanent dichotomy (such as seasonal moves), while the conflation of distance with the crossing of political/administrative boundaries is problematic (as people can move long distances within the same country or make international moves by travelling very short distances).

Figure 1.1 Temporal and spatial dimensions of human mobility

Permanent migration

Local migration Interregional migration International migration

Temporal migration

Commuting Circulation Long-distance commuting

Short-distance mobility Long-distance mobility

Source: Figure 2.2 (p. 25) in Malmberg, G. 1997. Time and space in international migration. In:

International Migration, Immobility and Development: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. T. Hammar, G. Brochmann, K. Tamas and T. Faist (eds). Oxford: Berg, pp. 21-48. © 1997 Tomas Hammar, Grete Brochmann, Kristof Tamas and Tomas Faist. Reproduced by permission of Berg Publishers, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Nevertheless, Malmberg’s broad division of moves into permanent or temporal remains useful. Following Roseman (1971), temporal moves can be defined as ‘circulation’ moves which are made out and back from a central residential location (for instance commuting or going on holiday). In contrast, permanent moves consist of changes in residential location and hence a change in the ‘centre of gravity’ of a person’s daily life. While permanent moves will trigger a reconfiguration of temporal mobility (for example as people adjust their commuting behaviour after moving house), the reverse relationship does not hold. Henceforth, this thesis focuses solely on permanent residential moves. Mobility and relocation are terms which are used to refer to these permanent changes of residence (although the term permanent will be dropped as it is somewhat problematic). Where temporal mobility is discussed, this is clearly identified (for instance by using terms such as commuting).

while defining migration as longer distance moves and moves made across international borders (Clark and Dieleman, 1996; Mulder and Hooimeijer, 1999). Given this terminological confusion, it is important for studies to clarify their use of these terms. For the purposes of this thesis, migration is defined as longer distance moves which result in the total displacement of daily activity spaces (Clark and Dieleman, 1996; Roseman, 1971). In contrast, all moves made over any distance within a single country are defined as residential mobility (hence residential mobility, mobility and relocation are terms which are used interchangeably to denote any type of internal residential move). These definitions are used because migration is arguably becoming increasingly synonymous with long distance and especially international moves (Ellis, 2012), while residential mobility more clearly captures the essence of residential relocation.

important to analyse residential mobility, as local moves may be more relevant to most people’s daily lives.

In his seminal study, Peter Rossi (1955) articulated a second reason to study internal residential mobility. Rossi contended that such research is important because the moving behaviour of individuals and households produces the demographic and socio-economic composition of places (Clark and Davies Withers, 2007). This can occur at a very broad scale, for instance as the age-selectivity of migration streams between different types of settlement alters the demographic composition of villages, towns and cities across a country (Dennett and Stillwell, 2010; Plane and Jurjevich, 2009). Equally, selective residential mobility patterns can also configure the finer scale ethnic and socio-economic geography of neighbourhoods (van Ham and Clark, 2009). The links between mobility and the geographic context are not unidirectional however, as ‘context’ in its broadest sense also influences mobility decision-making (Mulder and Hooimeijer, 1999).

Understanding the geographical patterns of mobility is important for a variety of reasons. In pragmatic terms, such knowledge is important when producing the population projections policymakers require to make informed planning and resource allocation decisions (Dennett and Stillwell, 2010; Rees et al., 2012). This is because as mobility alters the population composition of places, it also affects the current and future geography of demand for services and infrastructure. A detailed awareness of current mobility patterns can, therefore, help local authorities to determine whether it is for instance more pressing to invest in school places or care homes. Analysing mobility patterns is also valuable in less instrumental ways. At the broad scale, understanding urban processes such as segregation and gentrification requires detailed knowledge about the factors influencing people’s moving decisions. This is particularly relevant as mobility has traditionally been positioned as both the cause of and solution to many urban problems, such as the spatial concentration of poverty within metropolitan areas (Imbroscio, 2012).

paper, Wheaton (1990) drew on a long tradition of research in labour economics to theorise that residential mobility equilibrates both the housing and labour markets. Wheaton extended the concept of job matching to the housing market, arguing that households move in order to ‘match’ their housing supply to meet their changing needs. These insights suggest that the housing and labour markets are deeply interlinked, as job changes can trigger residential adjustments (and vice versa) (Clark and Davies Withers, 1999). Understanding how individuals and households make short distance moving decisions is therefore of crucial importance to understand how the housing and labour markets function (Henley, 1998; van der Vlist et al., 2002). This is particularly relevant in the context of the ongoing global recession, as it has been suggested that a vicious spiral of declining mobility rates and weakening labour and housing markets is developing in some Western countries (see Cooke, 2011).

In light of the above discussion, the rest of this chapter elaborates upon how this thesis develops our understanding of internal mobility within the United Kingdom (UK). The next section examines why it is important to conduct a longitudinal analysis which links mobility decision-making to subsequent moving behaviour. The chapter then discusses why it is particularly valuable to focus upon the realisation of moving desires. After presenting the overall objective of the study, the chapter concludes by outlining how the rest of the thesis is structured to fulfil this objective.

1.2 Linking mobility decision-making to actual moving

behaviour

1.2.1 Adopting a longitudinal life course perspective

Much of the migration and residential mobility literature therefore consists of cross-sectional analyses of migrants. These range from both aggregate and disaggregate quantitative analyses of the characteristics of movers (for recent examples Dennett and Stillwell, 2010; Finney, 2011; Niedomysl, 2011; Plane and Jurjevich, 2009), to qualitative studies of how individuals make housing choices when relocating (Levy et al., 2008; Munro and Smith, 2008).

This focus on mobility as a discrete and decontextualised event was criticised by Halfacree and Boyle, who commented that we need to move towards analysing mobility as an ‘action in time’ (1993: 337). Essentially, Halfacree and Boyle argue that treating residential moves as point-in-time events means that moves are divorced from the longer term context of the individual biographies within which they are situated (Findlay and Li, 1997). Halfacree and Boyle’s paper suggests that it is important to analyse residential mobility as a process which unfolds over time (Kley and Mulder, 2010), within the context of a person’s past experiences and their aspirations and expectations for the future.

which takes place over time within specific familial, temporal and socio-spatial contexts (Kley and Mulder, 2010).

Considering mobility to be a contextualised temporal process has motivated a growing number of studies to link mobility decision-making to subsequent moving behaviour. These longitudinal studies recognise that our understanding of migration and residential mobility can be greatly enhanced by studying more than just actual moving behaviour (Kan, 1999). Following people through time enables longitudinal analyses to build upon the insights provided by cross-sectional studies of what makes people think about moving (Kleinhans, 2009; McHugh et al., 1990; van Ham and Feijten, 2008), by investigating whether people who are thinking about moving subsequently go on to actually make residential moves.

1.2.2 Linking moving desires and subsequent moving behaviour

Over the last two decades, an increasing number of longitudinal studies have begun to link people’s expressed thoughts about moving to their subsequent moving behaviour (De Groot et al., 2011; Ferreira and Taylor, 2009; Kan, 1999; Lu, 1999a). These studies have largely overcome the twin problems of US-centrism and small sample sizes which characterised much of the longitudinal work conducted before the 1990s (Bach and Smith, 1977; Landale and Guest, 1985; Rossi, 1955; Speare et al., 1975; van Arsdol et al., 1968). Despite overcoming these issues, Kley (2011) cautions that much of the recent longitudinal literature nonetheless remains complex to interpret. She argues that this is partly due to a lack of conceptual clarity within studies. For example, many researchers fail to define and distinguish between conceptually distinct thoughts about moving (such as moving desires, intentions, plans or expectations). In addition, Kley (2011) notes that it is often difficult to compare the empirical findings of different studies because there is little uniformity in how moves are defined.

a ‘stated preference’ for relocation, in a way that expressing a moving intention or expectation cannot. While expressing a desire to move indicates that a person perceives that mobility will have positive consequences, moving intentions and expectations are more value-neutral thoughts about relocation. Conceptually, it is possible to intend or expect to behave in a certain way without wanting to do so.

Moving desires can also be considered to be stated preferences for relocation because they are expressed in direct response to the perceived deficiency of a person’s current housing and neighbourhood situation (van Ham and Feijten, 2008). While the feasibility of moving is unlikely to inhibit people from expressing moving desires, the restrictions and constraints which could impede relocation are likely to be considered in much greater detail before a moving intention or expectation is expressed (De Groot et al., 2011). Thus, while people who are dissatisfied with their home or neighbourhood are likely to desire to move (Speare et al., 1975), only those dissatisfied individuals who perceive that actually moving is possible will also express an intention or expectation of moving. As a result, studies linking moving intentions or expectations to actual moving behaviour may conflate people who want to move but who feel unable to do so with those who are content to remain at their current location. Hence, linking moving desires to subsequent moving behaviour provides the most suitable method of disaggregating whether residential (im)mobility behaviour is volitional or the result of restrictions and constraints (Buck, 2000a; Desbarats, 1983a).

(Cooke, 2008a). In these cases, one individual may be compelled to move or stay for the sake of their partner’s career (Smits et al., 2003). As a result, it is important to distinguish volitional residential moves from those which were undesired, as this distinction is likely to indicate the level of control a person has had over their moving behaviour. Examining the links between moving desires and subsequent moving behaviour can therefore reveal how different types of triggers and constraints lead to different mobility decision-making processes and different residential outcomes.

A second reason to analyse the links between moving desires and subsequent moving behaviour is that this framework enables the evaluation of urban policy. For many years, a large proportion of Western urban policies have been based around the assumption that selective mobility provides an important mechanism to alleviate many social problems (Imbroscio, 2012). For instance, policy initiatives designed to tackle concentrations of urban poverty have often involved encouraging the poor to relocate in order to stimulate gentrification and create mixed-income communities (Imbroscio, 2012). This liberal agenda is typically underpinned by a tacit belief that those people living in ‘suboptimal’ places (as occurs when the poor live in places with poor job access) must possess moving desires, which are somehow being frustrated by contextual circumstances. This may not always be the case, and Imbroscio (2012) suggests that greater attention also needs to be paid to ‘placemaking policies’ which seek to improve people’s lives in situ (for instance through investment in subsidised public transport and neighbourhood renewal).

and opportunity in housing across the country” (ODPM, 2005: 6). This emphasis on enhancing choice has been carried forward into the recent Coalition Government report Laying the Foundations: A Housing Strategy for England, which opens with the claim that “finding the right home, in the right place, can be an essential platform for people seeking to support their families and sustain work” (DCLG, 2011: 1). While laudable, such objectives are not unproblematic. Enabling people to exercise housing choice may in some circumstances conflict with policies seeking to improve deprived neighbourhoods (such as New Labour’s New Deal for Communities), where population churn motivated by residential dissatisfaction is sometimes seen as an impediment to the creation of sustainable communities (Beatty et al., 2009).

Linking the expression of moving desires to individuals’ subsequent moving behaviour can help to evaluate housing policy by uncovering the extent to which people are able to act upon their moving desires. According to Brown and King (2005), people can only exercise ‘real’ or effective choice when they are able to act upon a decision by selecting from amongst distinct alternatives. This definition suggests that exercising a choice to move or stay requires an individual to act in accordance with their previously expressed relocation preferences. If many people are unable to realise their moving desires, this suggests that people find it difficult to exercise housing choice (perhaps due to micro level restrictions or macro scale constraints). Investigating whether this is the case is particularly pertinent in the context of the current economic crisis, which is likely to have greatly increased the constraints faced by individuals who desire to move.

they dislike and want to leave may report lower levels of psychological well-being (Ferreira and Taylor, 2009). Such concerns are of particular relevance in the context of the Sustainable Communities Act 2007, which seeks to enhance the well-being of communities in England and Wales.

Given that constrained individuals such as the poor, ethnic minorities and social renters are disproportionately more likely to select into the least desirable areas, it seems possible that these individuals may also be more likely to express moving desires which they are then persistently unable to realise. Hence, investigating why some individuals do not act in accordance with their moving desires will shed light on the nature of the restrictions and constraints which most strongly affect the mobility process (Mulder and Hooimeijer, 1999). This will, in turn, contribute to our knowledge about the re-production of individual disadvantage, as well as highlighting how selective residential (im)mobility can contribute to the production of ethnically and socio-economically stratified neighbourhoods.

1.3 Thesis objective and structure

As a result of the above, the overall objective of this thesis is:

To gain insight into how the life course context affects both the expression of moving desires and the links between moving desires and subsequent moving behaviour.

outlined in Figure 1.2. Addressing these four sets of research questions fulfils the central objective of the thesis, as each is motivated by a clear gap in our knowledge of how moving desires are associated with subsequent residential (im)mobility over the life course.

Figure 1.2 Thesis structure

CHAPTER 1. Introduction

CHAPTER 2. Conceptual framework

Theme 1. Analysing the relations between moving desires, expectations and actual moving behaviour Theme 2. Investigating the linked lives of partners

Theme 3. Exploring the

biographical dimension of mobility

decision-making

Theme 4. Analysing desire abandonment and the

duration of wishful thinking

CHAPTER 3. Research design

CHAPTER 4.

A longitudinal analysis of moving desires,

expectations and actual moving behaviour CHAPTER 5. Partner (dis)agreement on moving desires and

the subsequent moving behaviour of

couples

CHAPTER 6.

Following people through time: An analysis of individual

residential mobility biographies

CHAPTER 7.

Wishful thinking and the abandonment of moving desires over

the life course

CHAPTER 8. Conclusions and discussion

Chapter three introduces the design of the studies conducted to address the research questions. The chapter commences by outlining the key philosophical and methodological considerations which influenced this thesis. Next, the chapter introduces and evaluates the types of data which could have been used to fulfil the thesis objective. Key issues such as the reasons for using secondary

data are discussed in some detail. The chapter concludes with a detailed discussion of the advantages and challenges of working with the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), the data source deemed most appropriate for this study. Taken together, chapters two and three introduce and discuss the extended conceptual and methodological framework which informed the empirical work conducted in this thesis.

Each of the four sets of research questions introduced in chapter two are then addressed in turn in chapters four to seven. Figure 1.2 illustrates that each set of research questions grouped into a theme is addressed in a specific chapter. For example, theme one questions are addressed in chapter four, while theme two questions are the focus of chapter five. These empirical chapters are structured as independent research papers. As these four chapters are separate papers, each has its own theoretical, methodological, analytical and conclusions sections. While this carries the risk that there will be some repetition of material, care has been taken to ensure that there is as little duplication as possible. While these chapters can be read independently, they are best read after reading chapters two and three. This is because the conceptual and methodological discussion in these early chapters provides a detailed contextualisation of the research reported in each paper. Chapters four to seven are also best read in order, as the insights gained from answering each set of research questions informed and influenced the subsequent analyses. By answering the four sets of research questions, these chapters combine to enhance our understanding of how moving desires are linked to subsequent moving behaviour over the life course.

moving desires as they are expressed in combination with moving expectations (thereby separating people who desire but do not expect to move from those who desire and expect to move). The analyses reveal important distinctions between people who do and do not expect to act upon their moving desires. This has important consequences for subsequent moving behaviour. The chapter argues that these insights enable us to more precisely predict residential moves, while also revealing the different mobility decision-making pathways individuals follow in response to different life course experiences.

Chapter five builds upon these findings to focus upon how the household context configures the likelihood of a person realising their moving desires. While life course theories emphasise that an individual’s behaviour is influenced by the people they live with (Bailey, 2009), most quantitative studies have so far neglected to analyse the intra-household dynamics of mobility decision-making (Sell and De Jong, 1978). This is particularly problematic when analysing the mobility behaviour of couples, as a large family migration literature has shown that couples make moving decisions at the household scale through the interactions between both partners (Cooke, 2008a). By linking together the records of partners in couples, chapter five explores whether the likelihood of an individual realising their moving desires is dependent upon the desires of their partner. The analyses demonstrate that individuals are far more likely to act upon a desire to move if this is shared with their partner. The chapter concludes by arguing that it is profitable to analyse households as collections of ‘linked lives’, as the life courses of others can both enable and constrain a person who wants to move from actually doing so.

constructing and visualising the seventeen-year mobility biographies of a panel of BHPS respondents, the chapter reveals that the implications of experiencing a particular event (such as making a desired move) can differ greatly depending on the long-term context within which this event is situated. The chapter also demonstrates that some people are persistently unable to act upon their moving desires for long periods of time.

The final empirical chapter (chapter seven) develops this longer term perspective, arguing that it is pertinent to investigate how long it takes individuals to fulfil their moving desires. The chapter enhances the existing literature by demonstrating that it is also important to investigate the abandonment of moving desires. The results obtained from descriptive analyses and event history models show that age, life course ties and commitments, socio-economic resources and life events all influence the duration and outcome of ‘wishful spells’ (periods where an individual consistently expresses a moving desire).

Chapter 2

Conceptual framework

Despite social scientists’ burgeoning interest in theorising and analysing diverse practices and experiences of mobility (Findlay et al., 2009), the previous chapter contended that it remains important to analyse the relocation behaviour of individuals within countries. It was argued that it is particularly valuable to link the expression of moving desires to subsequent moving behaviour within a longitudinal framework. As a result, chapter one concluded by stating that the objective of this thesis is to gain insight into how the life course context affects the expression and realisation of residential mobility desires. Fundamentally, meeting this objective will develop our understanding of the extent to which people are able to use relocation to attain their valued life goals (c.f. De Jong and Fawcett, 1981).

As a first step towards meeting this objective, chapter two articulates the theoretical context within which this thesis is situated. Given the huge quantity of studies of population mobility, the chapter does not claim to provide an exhaustive review of the literature on migration and residential mobility decision-making and behaviour. Instead, the chapter seeks to outline and explain the conceptual framework which provides the overarching structure linking together the empirical studies presented in chapters four to seven.

contextualised relationships between moving desires and subsequent moving behaviour. Four main gaps in our understanding of this process of mobility decision-making are then outlined and explored. Finally, the chapter then concludes with four sets of research questions designed to address these research gaps.

2.1 Analysing the geography of migration flows

2.1.1 Labour market perspectives

Scholarly interest in migration is often traced back to the publication of E.G. Ravenstein’s The Laws of Migration in 1885. In this influential paper, Ravenstein used census data to articulate a set of social ‘laws’ which he argued governed the patterns of population mobility in late nineteenth century Britain. Inspired by Ravenstein’s ecological approach, much twentieth century geographical research sought to identify, describe and analyse the geography of migration streams in Western (principally Anglophone) countries (Dennett and Stillwell, 2010). This interest in the geography of migration stimulated the development of a large number of migration models, each endeavouring to provide a conceptual framework for understanding population mobility patterns. These range from Stouffer’s (1940) contribution on the importance of intervening opportunities, through Lee’s (1966) ‘push-pull’ model to Zelinsky’s (1971) ambitious theory of mobility transitions (reviewed in Öberg, 1995; Speare et al., 1975).

epistemological boundaries, as both Marxist and positivist scholars often agree that migration is principally driven by economic forces.

While a range of economic theories have been advanced to explain the geography of migration (Öberg, 1995), neoclassical economic theory has had perhaps the most profound influence on how migration flows have been conceptualised and studied over the last half century. Within the neoclassical tradition, migration is conceptualised as a process which helps to maintain equilibrium within the labour market (Boyle and Shen, 1997; Öberg, 1995). At the national scale, neoclassical theory predicts that individuals migrate away from areas of low wages and high unemployment, in search of the better opportunities offered by areas with higher wages and lower unemployment rates (Böheim and Taylor, 2002; Drinkwater and Ingram, 2009). Neoclassical economics argues that this movement of population ought to be mirrored by a reverse flow of capital investment into areas where wages are low and potential profits are thus higher (Öberg, 1995). By exporting labour from areas of surplus to areas where labour is in demand, migration flows therefore contribute to reducing regional inequalities in wages and unemployment rates (Battu et al., 2005). This neoclassical argument that migration is a rational response to labour market disequilibrium has had a major influence on policymakers across the developed world. Many governments view migration as economically beneficial, believing that a spatially ‘flexible’ workforce should help to stimulate economic growth and reduce regional inequalities (Fischer and Malmberg, 2001; HM Treasury, 2008; McCormick, 1997).

rational decision influenced by similar considerations as the decision to invest in skills training or advanced education. As migration is an investment decision, Sjaastad contended that people will only migrate when they expect that the benefits of migration, minus the transaction costs of moving, outweigh the utility that the person expects to derive from remaining in place (Battu et al., 2005; Böheim and Taylor, 2002). As a result, Sjaastad theorised that migration can be considered to be a means of accumulating human capital, which should be remunerated with higher returns to an individual’s labour over their lifetime.

Although Sjaastad argued that people do not just consider pecuniary costs and benefits when deciding whether or not to move, many studies use human capital theory to argue that people migrate directly in order to receive higher wages (for instance Böheim and Taylor, 2007). While the returns to migration may indeed accrue quickly through immediate wage increases, migration can also be a more long-term investment strategy which is expected to yield benefits when considered within the context of the entire life course. This occurs when individuals migrate to accumulate human capital through education or skills training, for instance when people relocate to attend university or to progress in their chosen career. Conceptualising migration as a long-term investment decision has lead many authors to argue that migration can be considered to be a mechanism for effecting social mobility. Places with a high density of occupational opportunities, such as the South East of England, are therefore likely to be particularly attractive to migrants aspiring to become socially mobile by changing jobs and improving their skills (Fielding, 1992a).

2.1.2 Non-labour market explanations

patterns have sought to test this proposition, investigating whether migration is more than just a rational investment decision. For instance, several recent US and UK studies have disaggregated migration flows by stage in the life course. Using census data from the US and UK, Chen and Rosenthal (2008), Dennett and Stillwell (2010), Plane and Jurjevich (2009) and Plane et al. (2005) all found that people migrate to different types of places at different stages of the life course. While younger and more highly educated individuals tend to move to larger cities and places with a more dynamic economy, older people seem to move to areas with a better quality of life. These studies suggest that migration may only be a human capital investment strategy early in the life course. In contrast, the characteristics of the dwelling and neighbourhood as well as the amenities available within the local area may be more influential factors for the moving decisions of older people (Niedomysl and Hansen, 2010).

2.2 The value of disaggregate analysis

1Knowledge of the patterns of migration streams is valuable for policymakers, as the size and selectivity of migration flows to and from neighbourhoods, cities and regions influences the geography of population composition (Clark and Dieleman, 1996). Understanding migration flows and using these to derive population projections can therefore enhance planning and resource allocation decisions (Rees et al., 2012). As migration is an important component of demographic change, such research can also contribute to debates about broader social issues such as population ageing and changing patterns of ethnic diversity (Wilson and Rees, 2005). Nevertheless, it is arguable that there are three dimensions of the mobility process which are neglected by many aggregate analyses of migration flows. Analysing people’s motivations for moving, studying short distance residential mobility and investigating why people are residentially immobile all necessitate some form of disaggregate analysis.

2.2.1 Understanding why people move

Analysing why people move using data on migration flows is far from straightforward. As has long been recognised, such an approach can easily fall foul of the ecological fallacy by inferring individual motivations from aggregate patterns (Sell and De Jong, 1978). An important example of the problems this can create is discussed by Morrison and Clark (2011). These authors investigated why conclusions about the motivations for migration seem to differ strongly between aggregate analyses and cross-national evidence from micro-surveys. Broadly speaking, while economic factors emerge from aggregate analyses as the key motives for migration, micro-survey data suggests that most people report migrating over long distances for non-economic reasons (Niedomysl, 2011).

1

Morrison and Clark (2011) contend that to resolve these contradictory findings, we need to distinguish the factors which motivate moves from those which enable mobility (also Niedomysl, 2011). The authors propose that while continuity of employment may be necessary for people who want to migrate to actually do so, occupational advancement may not be the motive driving people to migrate. Instead, it is possible that many people wish to migrate for non-economic reasons, but only those who are able to secure ongoing employment at their chosen destination are able to actually act upon these desires. This selectivity of migrant flows could contribute to the oft-reported positive correlations between economic buoyancy and immigration, for the simple reason that economically buoyant regions produce more employment opportunities which enables more people to immigrate. In essence, Morrison and Clark (2011) are arguing that individuals may sometimes act as ‘satisficers’ in their occupational careers in order to attain valued non-economic goals through migration.

While qualitative evidence highlights the value of engaging with individuals to discover their motivations for moving, it is arguable that this can be more effectively accomplished at the population scale using social survey methods. The key to an effective survey of migrant motivations may be using open-ended questions which enable people to report multiple interlinked reasons for relocating (c.f. Halfacree and Boyle, 1993). Such an approach enables the analysis of migration processes at the macro scale, while overcoming the dangers of inferring the motivations for migration behaviour from the geography of migration flows.

2.2.2 Analysing short distance moves

Table 2.1 The distance over which residential moves are made in Britain

Distance moved (km) Share of within-UK moves (%)

0-2 44.4

3-4 10.8

5-6 6.3

7-9 6.0

10-14 5.6

15-19 3.2

20-29 3.4

30-49 3.4

50-99 4.8

100-149 3.3

150-199 2.6

200+ 6.1

Note: Excludes those with no usual address one year before the Census and those moving from outside the UK.

Source: Table 4.2 (p. 15) in Bailey, N. and Livingston, M. 2007. Population Turnover and Area Deprivation [a report for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation]. Bristol: The Policy Press.

Derived from 2001 Census data, Individual SARs, CAMS dataset. © Crown copyright 2007.

This general focus on population flows between large spatial units overlooks the importance of also analysing residential moves made over shorter distances. These moves are important for two principal reasons. Firstly (and as discussed in chapter one), analysing shorter distance mobility is valuable for the simple reason that short distance moves are much more common than longer distance migration (Long, 1992). For the UK, Table 2.1 provides data drawn from the Sample of Anonymised Records (SARs) on the distance over which British individuals moved in the year preceding the 2001 census (Bailey and Livingston, 2007). The table shows that the majority of moves were made over very short distances. Over 50% of movers moved fewer than 5km, while only 20.2% moved further than 30km. Bailey and Livingston’s (2007) results also show that 61% of movers moved within a single local authority district. As this short distance mobility is a key mechanism for (re)producing the geography of population composition (Clark and Ledwith, 2006), it is important to develop our understanding of the dynamics of shorter distance residential mobility.

thought to migrate over long distances primarily for economic reasons, while a desire to adjust housing and neighbourhood consumption is thought to be the dominant motivation for moves made over shorter distances (Lundholm et al., 2004; Niedomysl, 2011). This distance-motivation dichotomy is thought to exist as households are typically unwilling to migrate long distances to make housing and neighbourhood adjustments. This is because making long distance moves is disruptive and costly, as migration involves the total displacement of household members’ daily activity spaces (Roseman, 1971). Total displacement means that migrating individuals are no longer able to access the nodes (such as workplaces, schools, shops and social contacts) they previously visited as part of their daily routines. Long distance moves are also thought to be costly as a lack of information about the destination housing market can lead to suboptimal housing choices, necessitating further adjustment moves (Clark and Davies Withers, 2007; Roseman, 1971). As total displacement becomes less costly when children leave home and workplace ties are severed, there is evidence that long distance migration for environmental or amenity reasons is most common around retirement (see Duncombe et al., 2001).

labour and housing markets may also affect the destinations of long distance migrants.

To minimise the costs and disruption of moving, many studies argue that most individuals seek to move over short distances wherever possible. This is because shorter distance moves only involve the partial displacement of daily activity spaces. While partial displacement moves involve a change in dwelling, they do not require household members to change jobs, move schools or break their social networks (Roseman, 1971: 595), as typically occurs with longer distance migration. The boundary separating a total from a partial displacement move is likely to differ between individuals, depending upon their inclination and ability to invest in commuting and long distance travel. As it is usually possible to adjust housing and neighbourhood attributes by moving within the local area, households are unlikely to consider long distance migration if housing or neighbourhood factors are motivating a desire to move. As a result, analysing interzonal migration flows may not tell us much about the non-economic dimensions of mobility decision-making.

Re-examining why people move over any distance may also be becoming increasingly important if social and economic trends mean that it is becoming less appropriate to infer the motivations for moving from the distance over which a person moves (Clark and Huang, 2004). Clark and Huang (also Green, 2004) argue that the economic restructuring produced by globalisation may be altering mobility patterns. For instance, changes such as an increasing proportion of dual career households and the decentralisation of workplaces may alter the types and frequency of migration events. Demographic changes such as increasing rates of cohabitation and partnership dissolution may also alter the relationships between the motivation for moving and the distance over which moves occur (Flowerdew and Al-Hamad, 2004).

Buck, 2000b) and the US (Clark and Davies Withers, 2007). Nevertheless, it is important to note that the above studies still show that the relative importance of employment reasons does rise significantly as the distance moved increases. However, further justification for reconsidering the residential mobility-migration dichotomy comes from the accumulating evidence that people also often seek to reduce their commute times when making residential moves (Kim et al., 2005). These findings suggest that job factors may play a greater role in short distance residential mobility than has been typically acknowledged (Clark and Davies Withers, 1999). Given this growing complexity of residential mobility patterns and as people’s daily lives are increasingly configured by new forms and practices of mobility (Sheller and Urry, 2006), it seems valuable to analyse all forms of relocation behaviour. Given the practical difficulties associated with the analysis of population flows between small spatial areas, a deeper understanding of short distance mobility can be most easily achieved through a micro scale approach which analyses the mobility decision-making and behaviour of individuals and households.

2.2.3 The importance of residential immobility

migrate. Understanding why people are residentially immobile requires engaging with the attitudes of individuals through disaggregate analyses.

Analysing migration flows also contributes little to our understanding of the extent to which residential (im)mobility is a volitional process. Typically, many positivist studies argue or assume that people who move are ‘revealing’ their migration preferences (Timmermans et al., 1994 for discussion of stated and revealed preference modelling approaches). As a corollary, those who do not migrate are thought not to wish to move. However, insights from other epistemological perspectives suggest that we need to be cautious when viewing (non)migration as a ‘choice’ process. For Marxists, mobility behaviour is produced by an individual’s position within the class system, which is itself embedded within the structure of the capitalist economy (Fielding, 1992b). As a result, Marxists have traditionally disputed the notion that people are in control of their own moving behaviour and hence able to exercise ‘choice’. For many Marxists, the agency of individuals is limited as their behaviours are heavily constrained by wider economic structures (Lundholm et al., 2004).

In contrast, the idea that (non)migration is a choice is also contested by scholars influenced by structuration theory. Drawing on the work of Giddens, Halfacree and Boyle (1993) contend that moving decisions ought not to be considered to be the outcome of a completely deliberate and calculative process (McHugh, 2000). Instead, these authors argue that migration decisions also involve exercising ‘practical consciousness’, through drawing on everyday experiences and commonsense knowledges (McHugh, 2000). This nuances the idea that migration is a deliberative choice, suggesting that the biographical, household and wider cultural contexts within which decisions are made may have a considerable but often hidden influence on an individual’s relocation behaviour (Fielding, 1992b; Halfacree and Boyle, 1993).

1992b; Halfacree, 2004; Halfacree and Boyle, 1993). This approach recognises that household scale restrictions or macro contextual constraints may either impede migration or condition the destination choices available to people who want to move (Mulder and Hooimeijer, 1999). For example, the caring commitments of individuals can strongly configure (im)mobility behaviour (Bailey et al., 2004). At the macro scale, the structure of the British social housing sector has been shown to have traditionally acted as a constraint to the long distance migration of tenants (Boyle and Shen, 1997; Hughes and McCormick, 1981).

Developing our understanding of how such restrictions and constraints produce residential immobility is difficult if little is known about individuals’ stated preferences for relocation, as is the case in most ecological studies. Hence, studying only those individuals who move could lead to inaccurate predictions of future migration behaviour if the restrictions and constraints impeding individuals from acting upon their mobility preferences change over time. As a result, our understanding of residential mobility processes could be enhanced by directing greater attention towards the stated relocation preferences of both movers and non-movers. By linking stated preferences to subsequent behaviour, it is possible to analyse how the mobility decision-making process is affected by contextual opportunities, restrictions and constraints.

2.3 Why families move: Theorising residential mobility

2.3.1 Disequilibrium and residential mobility

altered the conventional wisdom about why people relocate. Rossi’s study has since inspired the development of a large residential mobility literature, much of which has adopted his micro scale (disaggregate) approach (Dieleman, 2001).

Following Rossi, many residential mobility studies contend that households move in response to disequilibrium (Boehm and Ihlanfeldt, 1986; Littlewood and Munro, 1997). While neoclassical theory conceptualises mobility as an anticipative utility maximising behaviour, residential mobility research has emphasised that disequilibrium in housing consumption also motivates households to relocate. In this perspective, people are thought to move home when their needs are no longer being met in their current dwelling and location (Rossi, 1955). This can occur when people perceive that their current dwelling and location do not match culturally constructed housing norms for people of their age (Morris et al., 1976; Morris and Winter, 1975). According to Morris and Winter (1975), culturally constructed space, tenure, structure, quality and neighbourhood norms are all likely to influence a person’s perception of disequilibrium and hence their relocation behaviour. Fielding’s (1992b) work suggests that the interplay between wider place cultures and a person’s self-image may also be an important factor motivating relocation. While much of the residential mobility literature focuses on these ‘housing’ components of disequilibrium, housing needs may also play a rather minor role in some moving decisions. Thus, labour force participation can also stimulate disequilibrium (for example to change jobs), as can educational events such as seeking to attend university.

complexity of making moving decisions, this adjustment process is rarely instantaneous. Hence, a substantial proportion of immobile households may be living with disequilibrium at any given moment (Littlewood and Munro, 1997).

Relocating to a new dwelling is rarely a perfect mechanism for the alleviation of disequilibrium (Littlewood and Munro, 1997). This is because the choice set of housing options accessible to a moving household is constrained, both by their access to resources and also by macro contextual factors such as the supply of housing in the destination area (Mulder and Hooimeijer, 1999). For instance, young adults leaving home are often prevented from entering homeownership due to a lack of financial capital. As affordable rental housing consists of certain types of dwelling concentrated in particular areas (in Britain, often small flats located in inner cities), this constrains the choice set accessible to young adults moving out of the parental home (van Ham, 2012). The destination choices of individuals are also likely to be configured by their motivations for moving, with some motivations producing a much more geographically specific search process than others. For example, moving decisions triggered by job changes, health needs or relocations motivated by household formation may involve a much more geographically constrained choice process than moves made to attain a better quality of life at retirement.

(as occurs before moving in with a partner) cannot be alleviated without a move. In addition, disequilibrium generated by neighbourhood dissatisfaction cannot easily be tackled without moving, as ‘voice’ strategies for modifying the neighbourhood via collective action are likely to take a considerable amount of time to become effective.

Secondly, individuals can also modify their perceptions of disequilibrium to ensure that their preferences and aspirations more closely match their current situation, negating the need for an adjustment move. This is likely to be most common when an individual perceives that they will be unable to move to adapt to their changing needs. Adjusting one’s perception of disequilibrium can be considered to be a type of cognitive dissonance reduction behaviour, carried out to help an individual reconcile themselves to living in a dwelling or location they would prefer to leave (Festinger et al., 1956). This reduction of cognitive dissonance is likely to be a key mechanism to preserve the subjective well-being of individuals, not least because a person’s home is a highly valued resource for their emotional security and sense of identity (Mason, 2004).

2.3.2 Residential mobility and the family life cycle

Figure 2.1 Stages in the family life cycle

Age Stage

0 Birth

10 Child

Adolescent

20 Maturity

Marriage

30 Children

40

Children mature 50

60

Retirement 70

Death

Source: Adapted from Figure 2.1 (p. 28) in Clark, W.A.V. and Dieleman, F.M. 1996. Households and Housing: Choice and Outcomes in the Housing Market. New Brunswick: Centre for Urban Policy Research. © 1996 Rutgers-The State University of New Jersey. Reproduced with the kind permission of Transaction Publishers, New Jersey.

Figure 2.2 Household transitions and changing housing needs

Source: Figure 2.2 (p. 29) in Clark, W.A.V. and Dieleman, F.M. 1996. Households and Housing: Choice and Outcomes in the Housing Market. New Brunswick: Centre for Urban Policy Research. © 1996 Rutgers-The State University of New Jersey. Reproduced with the kind permission of Transaction Publishers, New Jersey.