SPECIAL ARTICLE

The Future of Health Insurance for Children With

Special Health Care Needs

Paul W. Newacheck, DrPHa,b, Amy J. Houtrow, MD, MPHa, Diane L. Romm, PhDc, Karen A. Kuhlthau, PhDc, Sheila R. Bloom, MSc,

Jeanne M. Van Cleave, MDc, James M. Perrin, MDc

aDepartment of Pediatrics andbPhilip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, California;cCenter for Child and Adolescent Health Policy, Massachusetts General Hospital for Children, Boston, Massachusetts

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

ABSTRACT

CONTEXT.Because of their elevated need for services, health insurance is particularly important for children with special health care needs. In this article we assess how well the current system is meeting the insurance needs of children with special health care needs and how emerging trends in health insurance may affect their well-being.

METHODS.We begin with a review of the evidence on the impact of health insurance on the health care experiences of children with special health care needs based on the peer-reviewed literature. We then assess how well the current system meets the needs of these children by using data from 2 editions of the National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs. Finally, we present an analysis of recent developments and emerging trends in the health insurance marketplace that may affect this population.

RESULTS.Although a high proportion of children with special health care needs have insurance at any point in time, nearly 40% are either uninsured at least part of the year or have coverage that is inadequate. Recent expansions in public coverage, although offset in part by a contraction in employer-based coverage, have led to modest but significant reductions in the number of uninsured children with special health care needs. Emerging insurance products, including consumer-directed health plans, may expose children with special health care needs and their families to greater financial risks.

CONCLUSIONS.Health insurance coverage has the potential to secure access to needed care and improve the quality of life for these children while protecting their families from financially burdensome health care expenses. Continued vigilance and

advo-cacy for children and youth with special health care needs are needed to ensure that these children have access to

adequate coverage and that they fare well under health care reform.Pediatrics2009;123:e940–e947

C

HILDREN WITH SPECIAL health care needs (CSHCN) are those children who have or are at increased risk for a chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional condition and who also require health and relatedservices of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally.1They are among the most vulnerable of all

populations from a health vantage point and experience ongoing health issues that require continuing interaction with the health care system. CSHCN may require more frequent use of routine services such as office visits and highly specialized services, supplies, and equipment not typically used by other children.2–5

Health insurance coverage has the potential to secure access to needed care and improve the quality of life for

these children while protecting their families from financially burdensome health care expenses.6Recognizing the

important role that health insurance plays in the lives of CSHCN and their families, the Maternal and Child Health Bureau established a national goal in 1997 that all CSHCN should have continuous private or public health insurance that covers a reasonable share of health care costs and includes the health care services and providers needed by the child.7

The purpose for this article is to assess how well the current system is meeting the insurance needs of CSHCN and how emerging trends in health insurance may affect their well-being. The literature is rich with recent articles that have described the impact of health insurance on CSHCN, and the newly released 2005–2006 National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs (NSCSHCN) provides a wealth of timely data on the insurance character-istics of this population.

We begin with a review of the evidence on the impact of health insurance on the health care experiences of

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/ peds.2008-2921

doi:10.1542/peds.2008-2921

Key Words

insurance, access to care, quality of care, utilization, expenditures, special health care needs

Abbreviations

CSHCN— children with special health care needs

NSCSHCN—National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs SCHIP—State Children’s Health Insurance Program

FPL—federal poverty level PPO—preferred provider organizations HMO— health maintenance organization CDHP— consumer-directed health plan

CSHCN based on the peer-reviewed literature. We then assess how well the current system meets the needs of CSHCN by using data from 2 editions of the NSCSHCN. Finally, we discuss recent developments and emerging trends in the health insurance marketplace that may affect this population.

THE IMPORTANCE OF INSURANCE FOR CSHCN

In this section, we summarize the recent peer-reviewed literature concerning the effects of insurance for CSHCN. We discuss the impact of presence or absence of cover-age, type of coverage (private or public), payment mech-anism (fee-for-service or managed care), and adequacy of coverage on utilization, expenditures, access, and quality of care.

Utilization

Among CSHCN, insurance is associated with a signifi-cantly increased likelihood of receiving timely ambula-tory care5,8–10 and, overall, is associated with increased use of health care.11,12There is little difference in utiliza-tion rates between CSHCN with private and public

cov-erage. For example, Kuhlthau et al11 found no

differ-ences in subspecialty service use between children with different types of insurance. In contrast, payment mech-anism (fee-for-service or managed care) has been shown to affect utilization. Among publicly insured children with chronic conditions, managed care is associated with reduced use of inpatient care, outpatient hospital-based care, mental health care, prescription medications, and

durable medical equipment and supplies.13,14Preventive

care may be an exception; Mitchell et al15 found

im-proved compliance with American Academy of Pedi-atrics health supervision guidelines for those enrolled in Medicaid managed care versus fee-for-service,

whereas Garrett and Zuckerman16 found that

enroll-ment in Medicaid managed care did not affect receipt of well-child care or rates of visiting a health care professional.

Expenditures

Financially burdensome health care expenses are clearly mitigated by health insurance.17–19 Several studies have demonstrated that families of insured CSHCN are far better protected against burdensome out-of-pocket health care expenses than their uninsured counterparts.3,4,17,20,21Type of coverage is also associated with expenditures; the fami-lies of privately insured CSHCN have higher total

expen-ditures22,23 and spend more out-of-pocket than publicly

insured CSHCN.24

Access to Care

Overwhelming evidence indicates that CSHCN with in-surance fare better than uninsured children on a variety of access measures including having a usual source of care, access to specialists, unmet needs, and delayed/ forgone care.6,10,24–32Continuity of coverage also affects access to care. Continuously uninsured CSHCN fare worse than those with partial-year coverage, who, in turn, fare worse than those with full-year coverage.28,33

Parents of CSHCN with inadequate coverage (defined as insurance that only sometimes or never covers needed providers and services or pays less than a reasonable share of expenses) have also reported higher rates of unmet needs for routine services, delayed/forgone care, and difficulty receiving specialty referrals.27–29,31 Simi-larly, children with inadequate health insurance were statistically more likely to have unmet needs for therapy and supportive services than adequately insured CSHCN.34 The impact of type of insurance on access is less clear. Multiple recent studies have failed to show differences in access for publicly and privately sponsored insur-ance.11,26,29,30,32,35On the other hand, several studies have found that CSHCN with public insurance had better access to most services, with the possible exception of mental health services,9,25,36–39whereas a study by Newa-check et al8found that private insurance was associated with better overall access. Recent studies that examined payment mechanisms found more consistent results. Several recent studies showed that CSHCN enrolled in managed care fare better than their fee-for-service peers on access indicators.40–43

Health Care Quality

Evidence supporting the association between presence of insurance and improved health care quality is grow-ing, especially as it relates to satisfaction with care. Stud-ies have shown that caregivers of insured children were much more likely than their counterparts without insur-ance to report being satisfied with care.20,44 Moreover, families of CSHCN with insurance were more likely to

report that health care services were easy to use.44

CSHCN with insurance were also more likely to have access to comprehensive care in a medical home, which is a major quality indicator.45Adequacy of coverage also has been shown to affect satisfaction; caregivers of inad-equately insured CSHCN were approximately one half as likely as those with adequate coverage to report feeling like a partner in their child’s care and feeling satisfied with the care received.46

The literature shows that type of coverage and pay-ment mechanisms are related to quality of care. Two studies found that families of privately insured children were less likely to report dissatisfaction with care than publicly insured children.8,47However, Dick et al48found higher satisfaction ratings for children newly enrolled in the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP),

and Grossman et al49 identified higher family-rated

health care quality for CSHCN newly enrolled in a Med-icaid managed care plan. These findings could reflect improved quality of care, access, or both. Szilagyi et al47 found improvements in health care quality after enroll-ment in the SCHIP, especially for those children who

were previously uninsured. Similarly, Schuster et al50

The Overall Impact of Insurance

The recent literature evaluating health insurance over-whelmingly demonstrates its importance for CSHCN. There is substantial literature to support the positive effects of insurance on access to care, health care utilization, out-of-pocket expenses, and quality of care. Our review also indicates that continuity and adequacy of coverage are associated with better out-comes. The evidence regarding the impact of type of coverage (public or private) is mixed, whereas recent evidence on service-delivery systems has consistently shown that managed care can improve access to care for CSHCN.

HOW WELL DOES THE CURRENT SYSTEM MEET THE INSURANCE NEEDS OF CSHCN?

The preceding review indicates that health insurance effectively reduces financial barriers to needed care while protecting families against burdensome out-of-pocket expenditures. However, not all CSHCN have cov-erage, and not all coverage is adequate. In this section, we examine how well the system is meeting the insur-ance needs of CSHCN by using recently released data from the 2005–2006 NSCSHCN and its predecessor, con-ducted in 2001. These surveys provide the most current and complete information on the insurance characteris-tics of CSHCN. Data were drawn from Maternal and Child Health Bureau chart books for the national

sur-veys, 51,52 the Data Resource Center Web site (www.

cshcndata.org), and special tabulations provided by the Data Resource Center. All results discussed in the text are statistically significant at the .05 level. The surveys and their data-collection methodologies have been de-scribed in detail elsewhere.53,54

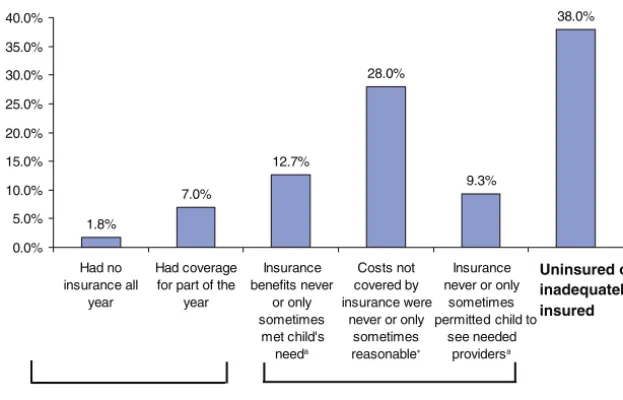

During 2005–2006, 91.2% of CSHCN, 9.3 million nationwide, were continuously covered by comprehen-sive health insurance for the 12 months preceding the survey interview. An additional 7.0% of CSHCN had coverage for part of the previous year, and 1.8% had no coverage at all during the year leading up to the

inter-view. Rates of coverage have improved significantly over time; the proportion of CSHCN without any coverage during the year declined by half since the 2001 survey was conducted.

Although coverage rates are high for CSHCN, the quality of that coverage is not always adequate from the families’ perspective. In the NSCSHCN, adequacy of cov-erage was measured as the composite of 3 indicators: whether health insurance benefits usually or always met the child’s needs; whether noncovered charges were usually or always considered reasonable; and whether the insurance usually or always allowed the child to see the providers thought to be needed by the parents. The proportion of CSHCN who met the 3 individual criteria in 2005–2006 was relatively high; among CSHCN in-sured at the time of the survey, 87.3% had benefits that met their child’s needs, 71.9% experienced reasonable charges, and 90.7% were able to see the providers needed by their child. However, only 66.9% were deemed to have adequate coverage as indicated by meet-ing all 3 criteria. Taken together, 38.0% of CSHCN, some 3.8 million nationally, were either uninsured or inade-quately insured (see Fig 1).

TRENDS IN HEALTH INSURANCE COVERAGE

Recent changes in the availability and affordability of private and public health insurance are affecting CSHCN and their families. The percentage of CSHCN with pri-vate health insurance has declined markedly, but ex-panded eligibility for public coverage as well as growth in other types of comprehensive coverage have more than offset that decline. As a result, both the number and proportion of CSHCN without any insurance coverage have diminished. In this section we describe these trends and their implications for CSHCN.

Erosion of Private Coverage

Although employers continue to be the dominant source of insurance coverage for families with CSHCN,

provi-1.8%

7.0%

12.7%

28.0%

9.3%

38.0%

0.0% 5.0% 10.0% 15.0% 20.0% 25.0% 30.0% 35.0% 40.0%

Had no insurance all

year

Had coverage for part of the

year

Insurance benefits never

or only sometimes

met child's needa

Costs not covered by insurance were

never or only sometimes reasonable∗

Insurance never or only

sometimes permitted child to

see needed providersa

Uninsured or inadequately insured

Uninsured Inadequately Insured

FIGURE 1

Uninsurance and underinsurance among CSHCN.aAmong

sion of private insurance has contracted in recent years. Data from the 2001 and 2005–2006 NSCSHCN showed that the proportion of CSHCN with private health insur-ance at the time of the survey fell 6.3 percentage points from 72.8% in 2001 to 66.5% in 2005–2006. Losses of private coverage are not unique to CSHCN. Private health insurance coverage rates declined at a similar rate for all children during this same period.55Moreover, the downward trend in private health insurance is not new. Rates of private coverage for children have been declin-ing since the mid-1970s.56,57

The growing cost of health insurance is usually cited by researchers as the primary contributor to the decline in employer-sponsored coverage. Indeed, employer sur-vey data show that in 2006, 74% of employers that were not offering health benefits cited high premiums as very important in their decision to not offer them.58Although health insurance premiums tend to follow a cyclical pattern, increases in premiums have commonly out-paced prices for other goods and services. For example, between 2001 and 2007, employer health insurance premiums jumped 78% while consumer prices as a

whole grew 17%.59 Employers have shouldered the

brunt of these added costs, but they have also shifted some costs to employees. From 2001 to 2007, annual worker contributions for family coverage increased 84%

to $3281 while wages increased only 19%.59,60The

up-ward trend in premium payments makes job-based in-surance increasingly less affordable in the face of stag-nant real wages for most American workers. Rising premiums may also be contributing to the stagnancy of real wages to the extent that employers contribute more toward insurance premiums in lieu of raising wages.

Structural changes in the economy have also contrib-uted to the decline in employer-based coverage. For example, from 2000 to 2006, there was a loss of 2.1 million goods-producing jobs (principally in manufac-turing) and a gain of 6.4 million service jobs in the US economy.61,62This shift in employment, part of a larger trend toward a service-based economy, has important insurance implications. Service-providing industries are much less likely than goods-producing industries to offer health insurance as a fringe benefit. During 2007, em-ployer-sponsored health insurance was offered to 85% of employees in goods-producing establishments but to only 67% of employees in service-providing establish-ments. Take-up rates are also lower in service jobs; 70% of eligible workers in service-providing establishments participated in employer-sponsored medical plans com-pared with 81% of employees in goods-producing estab-lishments during 2007.63

Expansions in Public Coverage

Federal and state initiatives to expand children’s eligibil-ity for public insurance have resulted in substantial gains in coverage for CSHCN. From 2001 to 2005–2006, the proportion of CSHCN with public coverage grew 5.7 percentage points from 29.8% to 35.5%. The upsurge in public coverage began in the late 1980s with a series of congressionally mandated state Medicaid-eligibility ex-pansions, followed by enactment of the SCHIP in 1997.

States are now required to extend Medicaid eligibility to all children aged 6 to 18 years in families with incomes below 100% of the federal poverty level (FPL), 133% of the FPL for children under the age of 6, and 185% of the FPL for infants. At their option, states may allow families with incomes above these limits but below 300% of the FPL to buy Medicaid coverage for their disabled children. In early 2008, SCHIP eligibility was set at a ceiling below 200% of the FPL in 6 states, from 200% to 249% of the FPL in 22 states, and atⱖ250% of the FPL in 23 states.64 During the 2007 debate on SCHIP reauthorization, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid issued a directive limiting federal SCHIP funding to families with incomes up to 250% of the FPL. Although the Obama adminis-tration has reversed this directive, the earlier threat of enforcement curtailed efforts in many states to expand SCHIP eligibility. Other changes in Medicaid regulations promulgated earlier in the decade may also substantially limit the value of public insurance for CSHCN through decreasing support for case management, curtailing cer-tain long-term care benefits, and restricting the ability of schools to receive Medicaid funds to support in-school health services for CSHCN.65

The Impact of Changes in Private and Public Coverage on CSHCN

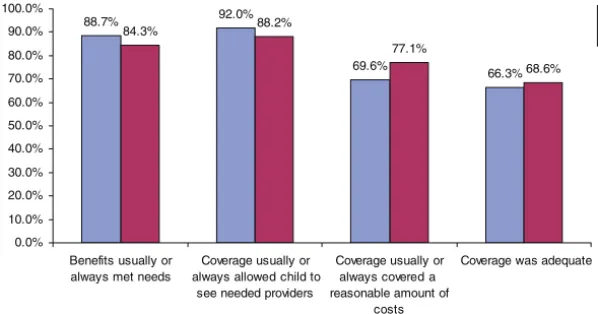

As the composition of health insurance coverage for CSHCN changes, it is important to consider how the shift in coverage from private to public may be affecting CSHCN and their families. We do that here by compar-ing family perceptions of the adequacy of their coverage. Using data from the 2005–2006 NSCSHCN, we assessed differences between private and public coverage across 3 key indicators of coverage adequacy (benefits, covered services, and noncovered charges). The data in Fig 2 show little difference in overall rates of adequate cover-age between privately and publicly insured CSHCN (66.3% vs 68.6%). However, families of privately in-sured CSHCN were more likely to report that their cov-erage offered benefits that met their child’s needs (88.7% vs 84.3%) and coverage that allowed them to see the providers they felt were needed for their child (92.0% vs 88.2%). In contrast and consistent with the literature, CSHCN with public coverage were more likely to report their noncovered costs as being reasonable compared with their counterparts with private coverage (77.1% vs 69.6%). Hence, although private and public coverage each offer distinct advantages, they offset each other in such a way that the overall adequacy of cover-age measured by the sum of these indicators is similar. This result suggests that the shift from private to public coverage may be largely benign for CSHCN and their families.

EMERGENCE OF NEW INSURANCE PRODUCTS

The last 2 decades have seen a major transformation in the way in which private and public health insurance is offered. Once the most common form of coverage, indemnity plans accounted for 73% of

3% of workers with employer coverage were enrolled in indemnity plans, whereas 57% were enrolled in preferred provider organizations (PPOs), 21% in health maintenance organizations (HMOs), and 13% in point-of-service plans, which combine features of HMOs

and PPOs.59 In the past few years, so-called

consumer-directed health plans (CDHPs) have emerged. These plans, which trade lower premiums for higher deductibles, ac-count for a small but growing segment of employer-based coverage.66

The old-style indemnity plans that were common-place before 1990 contained few provisions for con-trolling costs. Provider reimbursement was typically based on fee-for-service payment mechanisms, and consumer cost-sharing took the form of deductibles and coinsurance. The managed care plans that re-placed them, including HMOs, PPOs, and point-of-service plans, attempted to control health care costs through selective contracting with individual provid-ers and provider networks. Contracted providprovid-ers were given added financial incentives to control patient health care use. Initially, this led to concern among advocates for CSHCN that the shift from indemnity coverage to managed care could result in restricted provider choice and access to care.67,68Evidence on the effects of managed care for CSHCN has, for the most part, not supported the early concerns. In any event, its widespread adoption and the subsequent demise of indemnity coverage have made the debate largely moot.

The newer CDHPs retain a provider role in control-ling costs but give plan members greater responsibility for their own health care costs. CDHPs typically com-bine a high-deductible health plan (approximately $2000 for family coverage) with a health savings ac-count that enrollees can use to pay for a portion of their health care expenses. Plan sponsors often make an annual contribution to that account that covers some but not all of the deductible. Unused balances may be carried over for future use, giving plan mem-bers an incentive to use health care more prudently. The higher deductibles generally result in lower health insurance premiums because the enrollee bears

a greater share of the initial cost of care.58 Worker

premium contributions for CDHPs averaged $2856 an-nually for family coverage in 2007, compared with

$3311 for HMOs and $3236 for PPOs.59

Proponents contend that CDHPs can help restrain growth in health care costs. They maintain that because health savings account funds accrue over time, enrollees have an incentive to seek lower-cost health care services and to limit their discretionary spending on health care by obtaining care only when necessary. However, their potential as a cost-control strategy is limited because a small proportion of patients account for a large share of

health care spending.69 Approximately 10% of patients

account for 70% of health care spending in a year.70

Consequently, a large portion of health care spending falls outside the reach of patient cost-sharing provisions in high-deductible health plans. Spending that exceeds the deductible is subject to relatively weak financial incentives, and once the plan’s annual out-of-pocket maximum is reached, there are typically no financial incentives for patients to restrict their spending.71

Critics of CDHPs are concerned that the lower costs of these plans will attract healthier workers and their fam-ilies, driving up costs for other plan options. This is a particular concern for CSHCN and their families, given that few are likely to choose high-deductible health plans. Early experience suggests that CHDPs do attract

healthier members than competing HMOs and PPOs.72,73

There are also concerns that the high deductible in these plans will lead some enrollees to stint on needed care and that enrollees may not have adequate information to seek effective lower-cost health care services.58 Evi-dence from the Rand Health Insurance Experiment demonstrated that increased cost-sharing leads to de-creased use of both effective and ineffective services.74

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE FUTURE OF HEALTH INSURANCE FOR CSHCN

It is clear that health insurance effectively reduces bar-riers to care while protecting families against financially burdensome expenses. Although a high proportion of CSHCN have insurance at any point in time, nearly 40% are either uninsured at least part of the year or have inadequate coverage. On a positive note, recent expan-sions in public coverage contributed to a modest but

88.7% 92.0%

69.6%

66.3%

84.3% 88.2%

77.1%

68.6%

0.0% 10.0% 20.0% 30.0% 40.0% 50.0% 60.0% 70.0% 80.0% 90.0% 100.0%

Benefits usually or always met needs

Coverage usually or always allowed child to

see needed providers

Coverage usually or always covered a reasonable amount of

costs

Coverage was adequate Private Public

FIGURE 2

significant reduction in the number of uninsured CSHCN between 2001 and 2005–2006. Whether cover-age levels have continued to increase since then is un-known. However, the recent stalemate between

Con-gress and the Bush White House over SCHIP

reauthorization likely contributed to a deterioration of coverage for CSHCN since 2005–2006.

A larger concern is the continued deterioration of employer-based health insurance. Expansions of public coverage over the past 2 decades have effectively served as a holding action against the erosion of employer-sponsored private insurance. The major forces behind the decline in employer coverage (ever-increasing pre-mium costs and the ongoing restructuring of the econ-omy) show no signs of abating. As globalization contin-ues, further declines in the number of children covered through employer-sponsored plans seem inevitable. The severe economic contraction now underway is likely to further accelerate the decline in employer coverage. In the short-term, the recent reauthorization and expan-sion of the SCHIP should provide an effective stopgap. Ultimately, adoption of a publicly financed universal system, such as adding Medicare coverage for children, may be necessary to ensure that all children have access to coverage.

The large number of insured CSHCN with inadequate coverage presents another challenge. Although advo-cates have focused primarily on reducing the number of uninsured children, efforts are also needed to ensure that coverage, when available, meets the needs of fam-ilies in terms of provider selection, covered benefits, and level of cost sharing. Both public and private plans could be strengthened in this regard. Although public insur-ance programs are superior to private plans at limiting cost sharing, they do not perform as well in terms of provider selection and availability of services. In partic-ular, public beneficiaries, especially those enrolled in Medicaid, often have a limited choice of providers, and

even covered benefits can be difficult to access.75

Ad-dressing this issue requires infusing more funds into these primarily state-run programs to bring provider payment levels closer to those offered by private insur-ers. With the economic contraction, states are facing growing deficits, and many are turning toward trimming their programs. Additional federal Medicaid assistance provided under the American Recovery and Reinvest-ment Act of 2009 should help to prevent cuts in chil-dren’s health insurance at the state level.

Private insurance is more likely than public insurance to cover the providers needed by CSHCN but does less well than public coverage in leaving families with rea-sonable health care expenses. Some of the emerging insurance products, such as CDHPs, may exacerbate this problem. Better suited to healthy populations, they may undermine insurance offerings for CSHCN by siphoning healthy members from the risk pools that conventional plans use to establish their premiums. Although limited in market share for now, dour economic circumstances could result in more employers switching to these less expensive health insurance plans. Continued vigilance is

needed to ensure that these new offerings do not ad-versely affect CSHCN.

CONCLUSIONS

Pediatricians and other health care providers should re-main cognizant of the benefits of insurance and the negative effects of inadequate health coverage docu-mented here. Health care professionals can assume lead-ership roles in advocating for adequate health insurance for CSHCN by taking part in state and national advocacy efforts sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics and other organizations. With the continued erosion of employer-based insurance coverage, CSHCN are at ele-vated risk for losing coverage. Health care providers have a responsibility to promote adequate health insurance for vulnerable patients. The entities that finance health insurance also have a critical role. Private insurers, em-ployers, and government must work together to ensure that all children have health insurance that meets their needs. The health care reform initiatives now being de-veloped by the Obama administration may provide a vehicle for achieving this goal.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by Maternal and Child Health Bureau cooperative agreement U53MC04473.

We appreciate the helpful suggestions of our project advisory committee.

REFERENCES

1. McPherson M, Arango P, Fox H, et al. A new definition of children with special health care needs.Pediatrics.1998;102(1 pt 1):137–140

2. Houtrow A, Kim S, Newacheck P. Health care utilization, ac-cess and expenditures for infants and young children with special health care needs. Infants Young Child. 2008;21(2): 149 –159

3. Newacheck P, Kim S. A national profile of health care utiliza-tion and expenditures for children with special health care needs.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2005;159(1):10 –17

4. Newacheck PW, Inkelas M, Kim SE. Health services use and health care expenditures for children with disabilities. Pediat-rics.2004;114(1):79 – 85

5. Okumura MJ, McPheeters ML, Davis MM. State and national estimates of insurance coverage and health care utilization for adolescents with chronic conditions from the national survey of children’s health, 2003.J Adolesc Health.2007;41(4):343–349 6. Jeffrey AE, Newacheck PW. Role of insurance for children with special health care needs: a synthesis of the evidence.Pediatrics. 2006;118(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/ full/118/4/e1027

7. Honberg L, McPherson M, Strickland B, Gage JC, Newacheck PW. Assuring adequate health insurance: results of the Na-tional Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs. Pediatrics.2005;115(5):1233–1239

8. Newacheck PW, McManus M, Fox HB, Hung YY, Halfon N. Access to health care for children with special health care needs.Pediatrics.2000;105(4 pt 1):760 –766

10. Houtrow AJ, Kim SE, Chen AY, et al. Preventive health care for children with and without special health care needs.Pediatrics. 2007;119(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/ full/119/4/e821

11. Kuhlthau K, Nyman RM, Ferris TG, Beal AC, Perrin JM. Cor-relates of use of specialty care. Pediatrics.2004;113(3 pt 1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/113/3/e249 12. Witt WP, Riley AW, Coiro MJ. Childhood functional status,

family stressors, and psychosocial adjustment among school-aged children with disabilities in the United States.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2003;157(7):687– 695

13. Cebul RD, Solti I, Gordon NH, Singer ME, Payne SM, Gharrity KA. Managed care for the Medicaid disabled: effect on utiliza-tion and costs.J Urban Health.2000;77(4):603– 624

14. Davidoff A, Hill I, Courtot B, Adams E. Are there differential effects of managed care on publicly insured children with chronic health conditions? Med Care Res Rev. 2008;65(3): 356 –372

15. Mitchell JM, Gaskin DJ, Kozma C. Health supervision visits among SSI eligible children in the D.C. Medicaid program: a comparison of enrollees in fee-for-service and partially capi-tated managed care.Inquiry.2008;45(2):198 –214

16. Garrett B, Zuckerman S. National estimates of the effects of mandatory Medicaid managed care programs on health care access and use, 1997–1999.Med Care.2005;43(7):649 – 657 17. Chen AY, Newacheck PW. Insurance coverage and financial

burden for families of children with special health care needs. Ambul Pediatr.2006;6(4):204 –209

18. Kuhlthau K, Hill KS, Yucel R, Perrin JM. Financial burden for families of children with special health care needs.Matern Child Health J.2005;9(2):207–218

19. Newacheck PW, Stoddard JJ, Hughes DC, Pearl M. Health insurance and access to primary care for children.N Engl J Med. 1998;338(8):513–519

20. van Dyck PC, Kogan MD, McPherson MG, Weissman GR, Newacheck PW. Prevalence and characteristics of children with special health care needs.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2004;158(9): 884 – 890

21. Scurlock C, Yu S, Zhang X, Xiang H. Barriers to care among US school-aged children with disabilities.Pediatr Emerg Care.2008; 24(8):516 –523

22. Liptak GS, Shone LP, Auinger P, Dick AW, Ryan SA, Szilagyi PG. Short-term persistence of high health care costs in a na-tionally representative sample of children. Pediatrics. 2006; 118(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/118/ 4/e1001

23. Yu H, Dick A, Szilagyi PG. Does public insurance provide better financial protection against rising health care costs for families of children with special health care needs? Med Care. 2008; 46(10):1064 –1070

24. Bumbalo J, Ustinich L, Ramcharran D, Schwalberg R. Eco-nomic impact on families caring for children with special health care needs in New Hampshire: the effect of socioeco-nomic and health-related factors.Matern Child Health J.2005; 9(2 suppl):S3–S11

25. Dusing SC, Skinner AC, Mayer ML. Unmet need for therapy services, assistive devices, and related services: data from the National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs. Ambul Pediatr.2004;4(5):448 – 454

26. Huang ZJ, Kogan MD, Yu SM, Strickland B. Delayed or forgone care among children with special health care needs: an analysis of the 2001 National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs.Ambul Pediatr.2005;5(1):60 – 67

27. Kane DJ, Zotti ME, Rosenberg D. Factors associated with health care access for Mississippi children with special health care needs.Matern Child Health J.2005;9(2 suppl):S23–S31 28. Kogan MD, Newacheck PW, Honberg L, Strickland B.

Associ-ation between underinsurance and access to care among chil-dren with special health care needs in the United States. Pedi-atrics.2005;116(5):1162–1169

29. Smaldone A, Honig J, Byrne MW. Delayed and forgone care for children with special health care needs in New York state. Matern Child Health J.2005;9(2 suppl):S75–S86

30. Wang G, Watts C. Genetic counseling, insurance status, and elements of medical home: analysis of the National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs.Matern Child Health J. 2007;11(6):559 –567

31. Warfield M, Gulley S. Unmet need and problems accessing specialty medical and related services among children with special health care needs.Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(2): 201–216

32. Yu H, Dick AW, Szilagyi PG. Role of SCHIP in serving children with special health care needs.Health Care Financ Rev.2006; 28(2):53– 64

33. Olson LM, Tang SF, Newacheck PW. Children in the United States with discontinuous health insurance coverage.N Engl J Med.2005;353(4):382–391

34. Benedict RE. Quality medical homes: meeting children’s needs for therapeutic and supportive services.Pediatrics.2008;121(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/121/1/e127 35. Mayer ML, Skinner AC, Slifkin RT; National Survey of

Chil-dren With Special Health Care Needs. Unmet need for routine and specialty care: data from the National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs.Pediatrics.2004;113(2). Avail-able at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/113/2/e109 36. Krauss MW, Gulley S, Sciegaj M, Wells N. Access to specialty

medical care for children with mental retardation, autism, and other special health care needs. Ment Retard. 2003;41(5): 329 –339

37. Witt WP, Kasper JD, Riley AW. Mental health services use among school-aged children with disabilities: the role of socio-demographics, functional limitations, family burdens, and care coordination.Health Serv Res.2003;38(6 pt 1):1441–1466 38. Davidoff A, Kenney G, Dubay L. Effects of the State Children’s

Health Insurance Program expansions on children with chronic health conditions.Pediatrics.2005;116(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/116/1/e34

39. Tang MH, Hill KS, Boudreau AA, Yucel RM, Perrin JM, Ku-hlthau KA. Medicaid managed care and the unmet need for mental health care among children with special health care needs.Health Serv Res.2007;43(3):882–900

40. Mitchell JM, Gaskin DJ. Caregivers’ ratings of access: do chil-dren with special health care needs fare better under fee-for-service or partially capitated managed care.Med Care. 2007; 45(2):146 –153

41. Mitchell JM, Gaskin DJ. Do children receiving Supplemental Security Income who are enrolled in Medicaid fare better under a fee-for-service or comprehensive capitation model? Pediatrics.2004;114(1):196 –204

42. Mitchell JM, Gaskin DJ. Factors affecting plan choice and unmet need among supplemental security income eligible chil-dren with disabilities. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(5 pt 1): 1379 –1399

43. Roberto PN, Mitchell JM, Gaskin DJ. Plan choice and changes in access to care over time for SSI-eligible children with dis-abilities.Inquiry.2005;42(2):145–159

44. Ngui EM, Flores G. Satisfaction with care and ease of using health care services among parents of children with special health care needs: the roles of race/ethnicity, insurance, lan-guage, and adequacy of family-centered care.Pediatrics.2006; 117(4):1184 –1196

46. Oswald DP, Bodurtha JN, Willis JH, Moore MB. Underinsur-ance and key health outcomes for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2007;119(2). Available at: www. pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/119/2/e341

47. Szilagyi PG, Shone LP, Klein JD, Bajorska A, Dick AW. Im-proved health care among children with special health care needs after enrollment into the State Children’s Health Insur-ance Program.Ambul Pediatr.2007;7(1):10 –17

48. Dick AW, Brach C, Allison RA, et al. SCHIP’s impact in three states: how do the most vulnerable children fare?Health Aff (Millwood).2004;23(5):63–75

49. Grossman LK, Rich LN, Michelson S, Hagerty G. Managed care of children with special health care needs: the ABC program. Clin Pediatr (Phila).1999;38(3):153–160

50. Schuster CR, Mitchell JM, Gaskin DJ. Partially capitated man-aged care versus FFS for special needs children. Health Care Financ Rev.2007;28(4):109 –123

51. US Department of Health and Human Services.The National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs Chartbook 2005–2006.Rockville, MD: Health Resources and Services Ad-ministration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau; 2007 52. US Department of Health and Human Services.The National

Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs Chartbook 2001. Rockville, MD: Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau; 2004

53. Blumberg SJ, Olson L, Frankel M, et al. Design and operation of the National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs, 2001.Vital Health Stat 1.2003;(41):1–136

54. Blumberg SJ, Welch EM, Chowdhury SR, et al. Design and operation of the National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs, 2005–2006.Vital Health Stat 1.2008;(45): 1–197

55. Rhoades J.Health Insurance Status of Children in America, First Half 1996–2005: Estimates for the U.S. Civilian Noninstitutionalized Population Under Age18. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006. Statistical brief 131

56. Cunningham P, Kirby J. Children’s health coverage: a quarter-century of change.Health Aff (Millwood).2004;23(5):27–38 57. Newacheck PW, Hughes DC, Cisternas M. Children and health

insurance: an overview of recent trends.Health Aff (Millwood). 1995;14(1):244 –254

58. US Government Accountability Office. Employer-Sponsored Health and Retirement Benefits: Efforts to Control Employer Costs and the Implications for Workers.Washington, DC: US Government Accountability Office; 2007. GAO-07-355

59. Claxton G, Gabel J, DiJulio B, et al. Health benefits in 2007: premium increases fall to an eight-year low, while offer rates and enrollment remain stable. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007; 26(5):1407–1416

60. Claxton G, Gabel J, Gil I, et al. Health benefits in 2006: pre-mium increases moderate, enrollment in consumer-directed health plans remains modest.Health Aff (Millwood).2006;25(6): w476 –w485

61. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Current employment statistics survey table B-1. Available at: www.bls.gov/ces/home.htm. Accessed January 7, 2008

62. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employees on nonfarm payrolls by major industry sector, 1959 to date. Available at: ftp:// ftp.bls.gov/pub/suppl/empsit.ceseeb1.txt. Accessed January 7, 2008

63. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in Private Industry in the United States, March 2007. Washington, DC: US Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2007 64. Ross D, Horn A, Marks C. Health Coverage for Children and

Families in Medicaid and SCHIP: State Efforts Face New Hurdles—A 50-State Update on Eligibility Rules, Enrollment and Renewal Pro-cedures, and Cost-Sharing Practices in Medicaid and SCHIP in 2008. Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2008

65. Perrin JM, Boudreau AA. Reducing deficits and the health of children, youth, and families. Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6(4): 185–186

66. US Government Accountability Office.Consumer-Directed Health Plans: Small but Growing Enrollment Fueled by Rising Cost of Health Care Coverage. Washington, DC: US Government Accountability Office; 2006. GAO-06-514

67. Newacheck PW, Hughes DC, Stoddard JJ, Halfon N. Children with chronic illness and Medicaid managed care. Pediatrics. 1994;93(3):497–500

68. Hughes DC, Newacheck PW, Stoddard JJ, Halfon N. Medicaid managed care: can it work for children?Pediatrics.1995;95(4): 591–594

69. Gabel J, Pickreign J, Whitmore H.Behind the Slow Enrollment Growth of Employer-Based Consumer-Directed Health Plans. Wash-ington DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2006: 107. Issue Brief 107

70. Berk ML, Monheit AC. The concentration of health care ex-penditures, revisited.Health Aff (Millwood).2001;20(2):9 –18 71. Tu HT, Ginsburg PB.Benefit Design Innovations: Implications for

Consumer-Direct Health Care. Washington DC: Center for Study-ing Health System Change; 2007:109. Issue Brief 109 72. Parente ST, Feldman R, Christianson JB. Evaluation of the

effect of a consumer-driven health plan on medical care ex-penditures and utilization.Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 pt 2): 1189 –1210

73. Tollen LA, Ross MN, Poor S. Risk segmentation related to the offering of a consumer-directed health plan: a case study of Humana Inc.Health Serv Res.2004;39(4 pt 2):1167–1188 74. Anderson GM, Brook R, Williams A. A comparison of

cost-sharing versus free care in children: effects on the demand for office-based medical care.Med Care.1991;29(9):890 – 898 75. Perrin JM. EPSDT (Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis,

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-2921

2009;123;e940

Pediatrics

Bloom, Jeanne M. Van Cleave and James M. Perrin

Paul W. Newacheck, Amy J. Houtrow, Diane L. Romm, Karen A. Kuhlthau, Sheila R.

The Future of Health Insurance for Children With Special Health Care Needs

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/123/5/e940

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/123/5/e940#BIBL

This article cites 54 articles, 16 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/community_pediatrics Community Pediatrics

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-2921

2009;123;e940

Pediatrics

Bloom, Jeanne M. Van Cleave and James M. Perrin

Paul W. Newacheck, Amy J. Houtrow, Diane L. Romm, Karen A. Kuhlthau, Sheila R.

The Future of Health Insurance for Children With Special Health Care Needs

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/123/5/e940

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.