ARTICLE

Effects of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

and Venlafaxine During Pregnancy in Term and

Preterm Neonates

Ema Ferreira, BPharm, MSc, PharmD, FCSHPa,b, Ana Maria Carceller, MD, PhD, FRCPCc,d, Claire Agogue´, DPharma, Brigitte Zoe´ Martin, BPharm, MSca,b, Martin St-Andre´, MD, FRCPCd,e, Diane Francoeur, MD, FRCPCd,f, Anick Be´rard, PhDb,g

Departments ofaPharmacy (Centre IMAGe),cPediatrics,ePsychiatry,fObstetrics, andgResearch Center, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine, Montre´al, Que´bec,

Canada; Faculties ofbPharmacy anddMedicine, Universite´ de Montre´al, Montre´al, Que´bec, Canada

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES.Our goals were to (a) describe neonatal behavioral signs in a group of newborns exposed in utero to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or venlafax-ine at the time of delivery, (b) compare the rate of neonatal behavioral signs, prematurity, and admission to specialized neonatal care between a group of exposed and unexposed newborns, and (c) compare the effects in exposed preterm and term newborns.

PATIENTS AND METHODS.This was a retrospective cohort study including mothers taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or venlafaxine during the third trimester and mothers who were not taking any antidepressants, psychotropic agents, or benzodiazepines at the time of delivery of their newborns. Neonatal behavioral signs included central nervous, respiratory, and digestive systems, as well as hypoglycemia and the need for phototherapy.

RESULTS.Seventy-six mothers taking antidepressants and 90 untreated mothers and their newborns were analyzed. Smoking, alcohol intake, and substance abuse were more frequent among treated mothers. In infants in the exposed group, signs involving the central nervous and the respiratory systems were often observed (63.2% and 40.8%, respectively). These signs appeared during the first day of life, with a median duration of 3 days for exposed newborns. The signs resolved in 75% of cases within 3 to 5 days for term and premature newborns, respectively. All exposed premature newborns presented behavioral manifestations compared with 69.1% of term exposed newborns. Median length of stay was almost 4 times longer for exposed premature newborns than for those who were unexposed (14.5 vs 3.7 days).

CONCLUSIONS.Neonatal behavioral signs were frequently found in exposed new-borns, but symptoms were transient and self-limited. Premature infants could be more susceptible to the effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine.

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/ peds.2006-2133

doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2133

This work was presented in part at the clinical annual meeting for the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada; June 16 –21, 2005; Que´bec City, Que´bec, Canada; the joint annual meeting of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; October 18 –23, 2005; Toronto, Ontario, Canada; the annual meeting of the Canadian Paediatric Society, June 13–17, 2006; St-John’s, Newfoundland, Canada; and the 4e colloque annuel du Re´seau Me`re-Enfant de la Francophonie; June 8-9, 2006; Paris, France.

Key Words

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, venlafaxine, pregnancy, neonates, prematurity

Abbreviations

SSRI—selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

CHU—Centre Hospitalier Universitaire OR— odds ratio

CI— confidence interval Accepted for publication Sep 18, 2006

Address correspondence to Ema Ferreira, BPharm, MSc, PharmD, FCSHP, Department of Pharmacy, CHU Sainte-Justine, 3175 Coˆte Ste-Catherine, Montre´al, Que´bec, Canada H3T 1C5. E-mail: ema.ferreira@umontreal.ca

S

ELECTIVE SEROTONIN REUPTAKE INHIBITORS(SSRIs) and venlafaxine are prescribed for pregnant women with depressive or anxiety disorders.1–3 Sev-eral studies show that these treatments late in preg-nancy have potential effects on newborns, but they lack critical information about onset, duration, and severity of neonatal symptoms, all of which are essen-tial for clinical management of mothers and their in-fants.4–16 Moreover, to our knowledge, these studies did not differentiate these effects between term and preterm newborns. Indeed, some authors excluded premature infants from their studies. We have hy-pothesized that premature infants would be more sus-ceptible to complications after exposure to SSRIs and venlafaxine than term newborns.Our goals for this study were to (a) describe neonatal behavioral signs in a group of newborns exposed in utero to SSRIs and to venlafaxine at the time of delivery, (b) compare the rate of neonatal behavioral signs, pre-maturity, and admission to specialized neonatal care between a group of newborns who were exposed to SSRIs and venlafaxine at delivery and an unexposed group of newborns, (c) compare the effects in exposed preterm and term newborns.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study by using patients’ charts from Centre Hospitalier Universitaire (CHU) Sainte-Justine in Montre´al. This study was ap-proved by the institutional ethics board of CHU Sainte-Justine, a tertiary mother-child center with an average of 3500 deliveries per year and level 1, 2, and 3 neonatal care units. The study population included women who delivered at CHU Sainte-Justine between January 1, 2002, and July 31, 2004, and their newborns. We stud-ied 2 groups of women: those taking SSRIs or venlafax-ine and a control group. This study was conducted be-fore the Health Canada Advisory in August 2004 regarding the possible association between late exposure to SSRIs during pregnancy and adverse neonatal out-comes.17 Mothers using benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and any other antidepressant on a daily basis during pregnancy or at the time of delivery were excluded from exposed and unexposed groups. Other drugs for chronic diseases were permitted.

Study Groups

Exposed Group

We identified mothers taking SSRIs (citalopram, fluox-etine, fluvoxamine, paroxfluox-etine, or sertraline) or ven-lafaxine during the third trimester of pregnancy, or at least the 2 last weeks before delivery, through the phar-macy computerized system at CHU Sainte-Justine. Once identified, medical charts of mothers and infants were

retrieved for review. At low doses, pharmacological ef-fects of venlafaxine are similar to other SSRIs.

Unexposed Group

The unexposed group consisted of mothers who deliv-ered at CHU Sainte-Justine during the study period. To have at least a 1:1 ratio of exposed to unexposed pa-tients, we selected randomly 1 mother for every 25 deliveries through medical charts. No matching between exposed and unexposed subjects was performed. Charts of mothers and newborns were reviewed in a similar fashion to the exposed group.

Data Collection

Data collection was performed by a single investigator (Dr Agogue´). Maternal demographics and medical and psychiatric diagnoses were obtained from prenatal clin-ical assessment in the medclin-ical charts. Neonatal data were retrieved from medical and nursing observation notes for the first week of life or until discharge.

Outcome Measures

Neonatal behavioral signs were defined as a composite of signs and symptoms involving central nervous, respira-tory, and digestive systems, as well as hypoglycemia and the need for phototherapy. If at least 1 clinical manifes-tation involving any system cited above was observed during the study period (entered as yes/no in the daily data-collection sheet), it was considered that the infant had had a neonatal behavioral sign.

Infants were considered premature if they were born before 37 weeks of gestation according to ultrasound results and/or the first day of last menses. Levels 2 and 3 neonatal care were considered as specialized care units.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL). In the case of twin pregnancies, 1 sibling was selected randomly to avoid variable pairing problems. 2andt test analyses were used to compare

RESULTS

Seventy-six mothers who were taking SSRIs or ven-lafaxine at the time of delivery and their 79 infants (3 sets of twins) and 90 untreated mothers and their 91 infants (1 set of twins) met eligibility criteria and were considered for analysis.

Among exposed mothers, maternal psychiatric diag-noses were major depression (n ⫽ 31 [41%]), mixed disorders (n⫽20 [26%]), other anxiety disorders (n⫽

12 [16%]), generalized anxiety disorders (n ⫽ 11 [14%]), and unknown (n⫽2 [3%]). Forty-six (60.5%) were taking paroxetine (5– 40 mg), 10 (13.2%) fluox-etine (10 – 40 mg), 9 (11.8%) venlafaxine (75–150 mg), 6 (8%) citalopram (10 –30 mg), 3 (3.9%) sertraline (125–150 mg), and 2 (2.6%) fluvoxamine (50 –150 mg). In the treated group, 2 women were taking lithium and 1 olanzapine. According to medical chart information, the mean duration of SSRIs use was 32 months (range: 1–132 months) for the 61 mothers for whom the infor-mation was available.

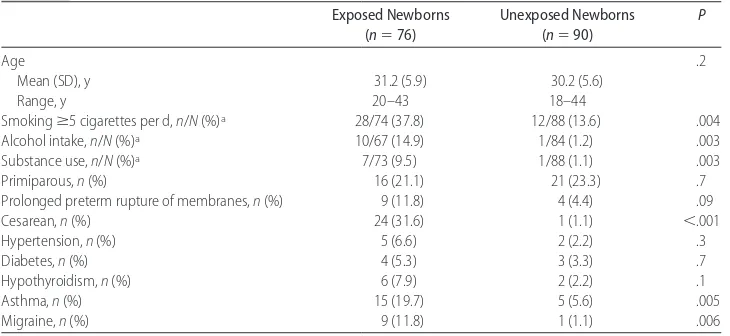

Smoking, alcohol intake, and substance abuse were more frequent among exposed mothers (P⬍.01) com-pared with unexposed mothers (Table 1). Asthma, mi-graine, and cesarean sections were also statistically more frequent in exposed women (P⬍.01).

First Outcome: Description of Neonatal Behavioral Signs

In our cohort of exposed infants, the median gestational age was lower when compared with unexposed infants, 38.3 weeks (interquartile range: 35.9 –39.7 weeks) vs 39.7 weeks (interquartile range: 38.6 – 40.3 weeks) (P⬍

.001). The signs most often observed involved the cen-tral nervous system (63.2%): tremors, shaking, agita-tion, spasms, hyper or hypotonia, irritability, and sleep disturbances (Table 2). Seizures were not observed. In our cohort, signs involving the respiratory system (40.8%) were indrawing, apnea/bradycardia, and tachy-pnea. Other differences observed in the exposed group

were higher rates of vomiting, tachycardia, and jaun-dice. Medical interventions included supportive care, ventilatory support, and the use of prophylactic antibi-otics; no term newborns needed to be intubated.

All neonatal signs appeared during the first day of life. The median duration of neonatal behavioral signs was 3 days for newborns exposed to SSRIs or venlafaxine. In exposed infants, 75% of these signs resolved after the fifth day for premature newborns (third day for term newborns) compared with 3 days for unexposed prema-ture infants (2 days for term unexposed newborns). The median length of stay was 3.9 days for exposed new-borns (interquartile range: 2.8 –7.1 days) vs 2.4 days for unexposed newborns (interquartile range: 2.1–2.8 days) (P⬍.001). When comparing premature newborns, ex-posed infants were hospitalized almost 4 times longer than unexposed infants, 14.5 days (interquartile range: 6.0 –26.4 days) vs 3.7 days (interquartile range: 2.8 – 6.4 days) (P⬍.001). The infants were not readmitted at the CHU Sainte-Justine later, but we cannot assess with certainty whether they were admitted in another med-ical center.

In the exposed group, we found the following mal-formations: phenotypic dimorphisms (2), absence of septum pellicidum (1), sagittal craniosynostosis (1), pul-monary peripheral stenosis (1), and hypospadias (1); no newborn presented with persistent pulmonary hyper-tension. In the control group we noted the following: phenotypic dimorphisms (3), angioma (1), heart mur-mur (1), and cryptorchidia (1).

Second Outcome: Comparison Between Exposed and Unexposed Newborns

Neonatal Behavioral Signs

The results of the comparison between the 2 groups are presented in Table 2. In univariate analyses, we observed a higher rate of neonatal behavioral signs among infants

TABLE 1 Maternal Characteristics

Exposed Newborns (n⫽76)

Unexposed Newborns (n⫽90)

P

Age .2

Mean (SD), y 31.2 (5.9) 30.2 (5.6)

Range, y 20–43 18–44

Smokingⱖ5 cigarettes per d,n/N(%)a 28/74 (37.8) 12/88 (13.6) .004

Alcohol intake,n/N(%)a 10/67 (14.9) 1/84 (1.2) .003

Substance use,n/N(%)a 7/73 (9.5) 1/88 (1.1) .003

Primiparous,n(%) 16 (21.1) 21 (23.3) .7

Prolonged preterm rupture of membranes,n(%) 9 (11.8) 4 (4.4) .09

Cesarean,n(%) 24 (31.6) 1 (1.1) ⬍.001

Hypertension,n(%) 5 (6.6) 2 (2.2) .3

Diabetes,n(%) 4 (5.3) 3 (3.3) .7

Hypothyroidism,n(%) 6 (7.9) 2 (2.2) .1

Asthma,n(%) 15 (19.7) 5 (5.6) .005

Migraine,n(%) 9 (11.8) 1 (1.1) .006

exposed to SSRIs or venlafaxine (77.6% vs 41.1%;P⬍

.001) compared with unexposed infants (Table 2). Ad-justed odds ratios (OR) for the effect of late exposure to SSRIs or venlafaxine and prematurity on neonatal be-havioral signs were 3.1 (1.3–7.1) and 8.0 (1.4 – 44.6), respectively (Table 3). Advanced maternal age and

smoking were also significantly associated with an in-creased risk of neonatal behavioral signs (Table 3).

Prematurity

The rate of prematurity was higher in the exposed group, 21 (27.6%) vs 8 (8.9%;P⫽.003). When

adjust-TABLE 2 Neonatal Behavioral Signs in Exposed and Nonexposed Newborns Exposed Newborns

(N⫽76),n(%)

Unexposed Newborns (N⫽90),n(%)

P

All neonatal behavioral signs 59 (77.6) 37 (41.1) ⬍.001

Central nervous system 48 (63.2) 20 (22.2) ⬍.001

Abnormal movements 31 (40.8) 10 (11) ⬍.001

Shaking 15 (19.7) 6 (6.7) .01

Agitation 19 (25) 4 (4.4) ⬍.001

Spasms 7 (9.2) 0 (0) .04

Tonus abnormalities 22 (28.9) 7 (7.8) ⬍.001

Hypertonia 7 (9.2) 0 (0) .004

Hypotonia 18 (23.7) 7 (7.8) .002

Irritability 15 (19.7) 1 (1.1) ⬍.001

Insomnia 16 (21.1) 9 (10) .047

Respiratory system 31 (40.8) 14 (15.5) ⬍.001

Indrawing 22 (28.9) 7 (7.8) ⬍.001

Apnea/bradycardia 13 (17.1) 1 (1.1) ⬍.001

Tachypnea 31 (40.8) 14 (15.6) ⬍.001

Other 31 (40.8) 12 (13.3) .08

Vomiting 11 (14.5) 4 (4.4) .03

Hypoglycemia 4 (5.3) 2 (2.2) .4

Tachycardia 12 (15.8) 3 (3.3) .006

Jaundice 17 (22.4) 5 (5.6) .001

a2or Fisher’s exact bilateral test.

TABLE 3 Univariate and Multivariate Analyses

Variable Crude OR

(95% CI)

Adjusted OR (95% CI)

Neonatal behavioral signs

SSRI exposure 5.0 (2.5–9.9) 3.1 (1.3–7.1)

Prematurity 13.3 (3.0–58.2) 8.0 (1.4–44.6)

Maternal age⬎35 y 2.1 (1.0–4.3) 2.6 (1.1–5.9)

Smoking 4.0 (1.7–9.4) 3.0 (1.1–7.9)

Illicit drug use 5.5 (0.7–45.3) 2.2 (0.2–21.6)

Cesarean section 4.6 (1.5–14.2) 1.1 (0.3–4.4)

Maternal hypertension 6.3 (1.4–28.5) 3.7 (0.7–20.3)

Prolonged preterm rupture of membranes 9.9 (1.3–77.7) 1.7 (0.1–19.7) Prematurity

SSRI exposure 3.9 (1.6–9.5) 2.4 (0.9–6.3)

Smoking 2.1 (0.9–5.0) 1.8 (0.7–4.7)

Maternal hypertension 4.0 (1.4–11.7) 2.5 (0.7–8.5)

History of prematurity 2.2 (1.0–4.9) 2.6 (1.0–6.6)

Maternal age⬎35 y 0.8 (0.3–2.0) 0.8 (0.3–2.2)

History ofⱖ2 miscarriages 0.8 (0.2–3.7) 0.4 (0.1–2.5)

Gestational diabetes 0.8 (0.2–3.0) 0.6 (0.2–2.4)

Admission to specialized care

SSRI exposure 6.1 (2.7–16.7) 2.4 (0.8–6.9)

Prematurity 17.4 (6.6–45.8) 7.7 (2.1–28.1)

Small for gestational age 3.4 (1.3–9.0) 3.0 (0.8–11.4)

Smoking 4.1 (1.9–8.9) 2.8 (1.0–8.1)

Illicit drug use 3.1 (0.8–13.2) 2.4 (0.5–12.0)

Cesarean section 7.5 (3.0–18.8) 2.2 (0.6–8.3)

Maternal hypertension 5.0 (1.8–14.2) 3.0 (0.7–12.2)

ing for confounding variables, exposure to SSRIs or ven-lafaxine was not associated with an increased risk of prematurity (Table 3).

Admission to Specialized Care

Multivariate analyses indicated that prematurity was the only variable that increased the risk of admission to specialized care (Table 3). Length of stay in NICUs was 1.5 days (interquartile range: 1– 6 days) vs 2.5 days (interquartile range: 1– 4 days) for exposed and unex-posed newborns, respectively (not significant). More-over, the length of stay among infants who were admit-ted in NICUs did not differ significantly between exposed and unexposed newborns at delivery with a median of 1 day for both groups (interquartile range: 1–5 days).

Third Outcome: Comparison Between Exposed Premature and Term Newborns

Premature infants represented 28% of the exposed co-hort and when excluding twin pregnancies, 6 (32%) presented with intrauterine growth retardation. Median gestational age for premature infants was 34 weeks (in-terquartile range: 32–34.7 weeks), median birth weight was 1794 g (range: 874 –2865 g), and median Apgar score at 5 minutes was 8 (range: 4 –10). Fifty-two per-cent of premature newborns were male. Cord pH was 7.3⫾0.1. In the exposed group, all patients with mal-formations were born prematurely. We found evidence that all premature newborns (100%) exposed to SSRIs or venlafaxine presented behavioral manifestations compared with 69.1% of term exposed newborns (P⫽

.002; Table 4). Median length of stay of exposed prema-ture infants and term newborns was 14.5 days

(inter-quartile range: 6.0 –26.4 days) vs 3.6 days (inter(inter-quartile range: 2.5– 4.2 days;P⬍.001).

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of depressive disorders during pregnancy has been estimated at 14%, and the incidence of anxiety disorders during pregnancy has been estimated as high as 21.9%.18–20In our study, mothers were treated mainly for major depression and mixed disorders. SSRIs and venlafaxine are the treatments most often prescribed for these disorders, and continued treatment may be needed throughout pregnancy for maternal well-being. Because nontreatment or suboptimal treatment could affect an-tenatal and postnatal maternal well-being and early mother-infant interactions, it is recommended to opti-mize treatment during pregnancy instead of abruptly discontinue treatment.21Several studies and case series associated these antidepressants used near term to neo-natal complications.9–16,22–30

To ensure that mothers were really taking their med-ications, we used several methods of verification, includ-ing pharmacy and medical charts. In our cohort, parox-etine was used in the majority of the cases. During data analysis, we tried to analyze the effects of paroxetine on adverse pregnancy outcomes; however, we chose not to report it because the numbers were too small to be clinically significant. In our cohort, cigarette use, alcohol intake, and substance abuse were statistically more fre-quent among treated mothers; this finding is consistent with others studies.31–33

Despite all the literature on the topic, the decision to continue or to stop antidepressant treatment during pregnancy remains a current challenge for clinicians. In

TABLE 4 Behavioral Signs in Exposed Premature and Term Newborns Exposed Premature Newborns

(N⫽21),n(%)

Exposed Term Newborns (n⫽55),n(%)

P

All neonatal behavioral signs 21 (100) 38 (69.1) .002

Central nervous system 20 (95.2) 28 (50.9) ⬍.001

Abnormal movements 14 (66.7) 17 (30.9) .005

Shaking 4 (19) 11 (20) 1

Agitation 10 (47.6) 9 (16.4) .005

Spasms 3 (14.3) 4 (7.3) .4

Tonus abnormalities 13 (61.9) 9 (16.4) ⬍.001

Hypertonia 3 (14.3) 4 (7.3) .4

Hypotonia 11 (52.4) 7 (12.4) ⬍.001

Irritability 5 (23.8) 10 (18.2) .6

Insomnia 5 (23.8) 11 (20) .7

Respiratory system 14 (66.7) 14 (25.5) ⬍.001

Indrawing 10 (47.6) 12 (21.8) .03

Apnea/bradycardia 8 (38.1) 5 (9.1) .003

Tachypnea 13 (61.9) 18 (32.7) .02

Other 18 (85.7) 6 (10.9) ⬍.001

Vomiting 4 (19) 7 (12.7) .5

Hypoglycemia 4 (19) 0 (0) .005

Tachycardia 8 (38.1) 4 (7.3) .003

Jaundice 15 (71.4) 2 (3.6) ⬍.001

2004, the US Food and Drug Administration and Health Canada cautioned health care professionals and patients about neonatal effects and late pregnancy exposure to SSRIs and related compounds.17,34Some authors believe those recommendations were only partially evidence-based and may lead the depressed mother to be at a health risk, which was the reason why we chose all patients who were born before these advisories.14

Growing data indicate that these medications are not teratogenic6,25,35–38except for paroxetine, which has re-cently been associated with a risk of cardiovascular birth defects.39 Glaxo Smith Kline39 and Kallen40suggested a possible risk of cardiovascular malformations in neo-nates born from women taking paroxetine. In our co-hort, we report 1 absence of septum pellicidum as pre-viously described by Hendrick.13We only found 1 patient with peripheral pulmonary stenosis after his mother took paroxetine for 1 year. Persistent pulmonary hyper-tension of the newborn was also associated with the maternal use of SSRIs in the second half of pregnan-cy,41,42but clinically we did not find any persistent pul-monary hypertension of the newborn among our sub-jects. In our cohort, there were no neonatal deaths attributable to neonatal SSRI exposure. Indeed, rare re-ports of serious complications related to these treatments have been published.4,14

In recent years, several studies and case series have been published indicating that SSRIs and venlafaxine were associated with a variety of neonatal complications including neonatal behavioral signs, mainly respiratory and central nervous symptoms, prematurity, low birth weight, and increased admission to neonatal specialized care units.6,9,33 Recently, Levinson-Castiel23 found that 30% of exposed newborns presented neonatal behav-ioral signs; in our cohort, 77.6% of exposed newborns presented abnormal movements, hypo/hypertonia, in-somnia, and dyspnea. The way we conducted our data collection could explain our higher rates of neonatal manifestations in exposed and unexposed groups com-pared with other studies. Our results are consistent with those observed by Sanz,28who reported more neurologic symptoms. In our cohort of exposed newborns, we found a significant association with neonatal behavioral signs, the ORs were similar to those found by Lattimore43 (4.1 [95% CI: 1.2–19.9]) and by Moses-Kolko4 (3.0 [95% CI: 2.0 – 4.4]) in a literature review. In our study, no glycemic effects were found, unlike others.22,29

Most published studies lacked critical data regarding the onset, duration, and severity of neonatal symptoms, all of which are essential for clinical management of mothers and their infants. In our study, these signs were observed within the first 3 days of life and lasted up to 5 days after birth. Despite our higher incidence, symptoms were transient and self-limited, and symptomatic infants were managed with supportive care. Our results are similar to those found by Levinson-Castiel.23Our study,

like others, is not able to assess whether symptoms result either from SSRI withdrawal or from a type of serotonin-ergic syndrome.14

Several studies showed an association between the use of SSRIs during pregnancy and an increased rate of preterm birth.6,16,33In our cohort, the rate of prematurity was higher in the exposed group, but when adjusted for different variables, the exposure to SSRIs or venlafaxine was not associated with an increased risk of prematurity. In our analysis, none of the known risk factors for pre-maturity, including smoking and maternal hyperten-sion, could explain our higher rate of prematurity.

Premature infants show more lung and central ner-vous system immaturity, which predispose them to more respiratory problems, irritability, and convulsions. Despite our small sample size, we were able to assume that after exposure to SSRIs or venlafaxine, premature infants are more susceptible than term newborns to these complications. However, our study cannot deter-mine whether these neonatal signs were related to SSRI exposure or to the vulnerability inherent to prematurity because we had only 8 unexposed premature infants. In our cohort, prematurity was the only variable that in-creased the risk of admission to a specialized care and not the exposure to SSRIs or venlafaxine. Indeed, in our exposed patients, adjusted ORs were 2.4 (95% CI: 0.9 – 6.3) and 2.4 (95% CI: 0.8 – 6.9) for prematurity and admission to specialized care unit similar to 1.9 (95% CI: 0.8 – 4.3) and 3.3 (95% CI: 1.5–7.5) found by Latti-more.43 In the literature, there are only case reports or short series of cases of neonatal behavioral signs associ-ated with the use of SSRIs by pregnant women, but we did not find any series with premature infants. Our study specifically focused on the consequences of these treat-ments for exposed premature infants.30

CONCLUSIONS

Neonatal behavioral signs are more frequently observed in newborns exposed to SSRIs or venlafaxine; however, symptoms are transient and self-limited. Premature in-fants are more susceptible to the effects of these antide-pressants than term newborns.

When indicated, antidepressant treatment may be continued until the end of pregnancy to maintain opti-mal maternal mental health and function and to prevent maternal postnatal decompensation and disturbances of early mother-infant interactions. Pregnant women and clinicians should be aware of the potential adverse ef-fects and the risks and benefits of treatment with SSRIs and venlafaxine, and the decision to continue with the treatment should be considered depending on the case.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Drs Ferreira and Be´rard and Ms Martin are on the Re-search Chair on Medication, Pregnancy and Lactation of the Faculty of Pharmacy, Universite´ de Montre´al. Dr Be´rard received a career award from the Canadian In-stitutes of Health Research and the Health Research Foundation.

We thank Jean-Franc¸ois Bussie`res for continuous support and Myles Lee Masley for manuscript review.

REFERENCES

1. Altshuler LL, Cohen L, Szuba MP, Burt VK, Gitlin M, Mintz J. Pharmacologic management of psychiatric illness during pregnancy: dilemmas and guidelines. Am J Psychiatry. 1996; 153:592– 606

2. Koren G, Pastuszak A, Ito S. Drugs in pregnancy.N Engl J Med.

1998;338:1128 –1137

3. Nonacs R, Cohen LS. Assessment and treatment of depression during pregnancy: an update.Psychiatr Clin North Am.2003;26: 547–562

4. Moses-Kolko EL, Bogen D, Perel J, et al. Neonatal signs after late in utero exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors: litera-ture review and implications for clinical implications.JAMA.

2005;293:2372–2383

5. Casper R, Fleisher BE, Lee-Ancajas JC, et al. Follow-up of children of depressed mothers exposed or not exposed to an-tidepressant drugs during pregnancy. J Pediatr. 2003;142: 402– 408

6. Chambers CD, Johnson KA, Dick LM, Felix RJ, Jones KL. Birth outcomes in pregnant women taking fluoxetine.N Engl J Med.

1996;335:1010 –1015

7. Cissoko H, Swortfiguer D, Giraudeau B, Jonville-Bera AP, Au-tret-Lera C. Neonatal outcome after exposure to selective se-rotonin reuptake inhibitors late in pregnancy [in French].Arch Pediatr.2005;12:1081–1084

8. Cohen LS, Heller VL, Bailey JW, Crush L, Ablon JS, Bouffard SM. Birth outcomes following prenatal exposure to fluoxetine.

Biol Psychiatry.2000;48:996 –1000

9. Costei AM, Kozer E, Ho T, Eto S, Koren G. Perinatal outcome following third trimester exposure to paroxetine.Arch Pediatr Adolesc.2002;156:1129 –1132

10. Gentile S. The safety of newer antidepressants in pregnancy and breastfeeding.Drug Safety.2005;28:137–152

11. Goldstein DJ. Effects of third trimester fluoxetine exposure on the newborns.J Clin Psychopramacol.1995;15:417– 420 12. Hendrick V, Stowe ZN, Altshuler LL, Hwang S, Lee E, Haynes

D. Placental passage and antidepressant medications. Am J Psychiatry.2003;160:993–996

13. Hendrick V, Smith LM, Suri R, Hwang S, Haynes D, Altshuler L. Birth outcomes after prenatal exposure to antidepressant medication.Am J Obstet Gynecol.2003;188:812– 815

14. Koren G, Matsui D, Einarson A, Knoppert D, Steiner M. Is maternal use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the third trimester of pregnancy harmful to neonates?CMAJ.2005; 172:1457–1459

15. Laine K, Heikkinen T, Ekblad U, Kero P. Effects of exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy on serotoninergic symptoms in newborns and cord blood mono-amine and prolactin concentrations.Arch Gen Psychiatry.2003; 60:720 –726

16. Wen SW, Yang Q, Garner P, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and adverse pregnancy outcomes.Am J Obstet Gy-necol.2006;194:961–966

17. Health Canada. Health Canada to examine SSRIs and children. Available at: www.cpa-apc.org/publications/archives/Bulletin/ 2004/april/news32En.asp. Accessed July 10, 2006

18. Hallbreich U. Prevalence of mood symptoms and depression during pregnancy: implications for clinical practice and re-search.CNS Spectr.2004;9:177–184

19. Wisner KL, Gelenberg AJ, Leonard H, Zarin D, Frank E. Phar-macologic treatment of depression during pregnancy.JAMA.

1999;282:1264 –1269

20. Heron J, O’Connor TG, Evans J, Golding J, Glover V; The ALSPAC Study Team. The course of anxiety and depression through pregnancy and the postpartum in a community sam-ple.J Affect Disord.2004;80:65–73

21. Koren G. Discontinuation syndrome following late pregnancy exposure to antidepressants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004; 158:307–308

22. Kallen B. Neonate characteristics after maternal use of antidepres-sant in late pregnancy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158: 312–316

23. Levinson-Castiel R, Merlob P, Linder N, Sirota L, Klinger G. Neonatal abstinence syndrome after in utero exposure to se-lective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in term infants.Arch Pe-diatr Adolesc Med.2006;160:173–176

24. Nordeng H, Lindemann R, Perminov KV, Reikvam L. Neo-natal withdrawal syndrome after in utero exposure to selec-tive serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Acta Paediatr. 2001;90: 288 –291

25. Oberlander TF, Misri S, Fitzgerald CE, Kostaras X, Rurak D, Riggs W. Pharmacologic factors associated with transient neo-natal symptoms following preneo-natal psychotropic medication exposure.J Clin Psychiatry.2004;65:230 –237

26. Pan JJ, Shen WW. Serotonin syndrome induced by low dose of venlafaxine.Ann Pharmacother.2003;37:209 –211

27. Santos RP, Pergolizzi JJ. Transient neonatal jitteriness due to maternal use of sertraline.J Perinatol.2004;24:392–394 28. Sanz EJ, De-las-Cuevas C, Kiuru A, Bate A, Edwards R.

Selec-tive serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnant women and neonatal withdrawal syndrome: a database analysis. Lancet.

2005;365:482– 487

29. Stiskal JA, Kulin N, Koren G, Ho T, Ito S. Neonatal paroxetine withdrawal syndrome.Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal.2001;84: F134 –F135

30. Zeskind PS, Stephens LE. Maternal selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor use during pregnancy and newborn neurobe-havioral.Pediatrics.2004;113:368 –375

31. Orr ST, Miller CA. Maternal depressive symptoms and the risk of poor pregnancy outcome: review of the literature and pre-liminary findings.Epidemiol Rev.1995;17:165–171

inhibitors: a prospective controlled multicenter study.JAMA.

1998;279:609 – 610

33. Simon GE, Cunningham ML, Davis RL. Outcomes of prenatal antidepressant exposure.Am J Psychiatry.2002;159:2055–2061 34. US Food and Drug Administration. Questions and answers on antidepressant use in children, adolescents, and adults. Available at: www.fda.gov/cder/drug/antidepressants/ Q&A_antidepressants.htm. Accessed July 10, 2006

35. Einarson A, Fatoye B, Sarkar M, et al. Pregnancy outcome following gestational exposure to venlafaxine: a multicenter prospective controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158: 1728 –1730

36. Pastuszak A, Schick-Boschetto B, Zuber C, et al. Pregnancy outcome following first-trimester exposure to fluoxetine (Prozac).JAMA.1993;269:2246 –2248

37. Goldstein DJ, Sundell KL, Corbin LA. Birth outcomes in preg-nant women taking fluoxetine. N Engl J Med. 1997;336: 872– 883

38. Ericson A, Kallen B, Wiholm B. Delivery outcome after the use of antidepressants in early pregnancy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol.

1999;55:503–508

39. GlaxoSmithKline. EPIP083: Updated preliminary report on bu-propion and other antidepressants, including paroxetine, in pregnancy and the occurrence of cardiovascular and major congenital malformation. Available at: http://ctr.gsk.co.uk/ Summary/paroxetine/studylist.asp. Accessed November 2, 2006

40. Kallen B, Otterblad Olausson P. Antidepressant drugs during pregnancy and infant congenital heart defect.Reprod Toxicol.

2006;21:221–222

41. Chambers CD, Hernandez-Diaz S, Van Marter LJ, et al. Selec-tive serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and risk of persistent pul-monary hypertension on the newborn.N Engl J Med. 2006; 354:579 –587

42. Wooltorton E. Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the

newborn and maternal use of SSRIs. CMAJ. 2006;174:

1555–1556

43. Lattimore KA, Donn SM, Kaciroti N, Kemper AR, Neal CR Jr, Vazquez DM. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use during pregnancy and effects on the fetus and newborn: a meta-analysis.J Perinatol.2005;25:595– 604

QUACKSPERTISE

“A recent decision by a New York court is a stark reminder that despite far-reaching reforms junk science still plagues American court rooms. The case,Nonnon v. City of New York, involves a group of plaintiffs claiming that exposure to toxic substances in New York City’s Pelham Bay landfill caused their cancers. They presented no study to the trial court showing that any substance found in the landfill causes their types of cancer; and the testimony of their expert witnesses was speculative and based on a single methodolog-ically deficient study. . . . The outcome would likely have been different had the suit been brought in federal court. That’s because cases based on the sorts of ‘quackspertise’ that once led to multimillion dollar payouts for trial law-yers— claims that breast implants cause immune-system disease, power lines cause leukemia, vaccines cause autism, and the like—now routinely get dismissed before trial. The reason is a strict reliability test for expert testimony first announced by the US Supreme Court in the 1993 case of Daubert v. MerrellDow Pharmaceuticals. ButDaubert’sreliability test, codified in Federal Rule of Evidence 702, only governs federal trials. Plaintiffs with personal injury claims backed by dubious (or worse) expert testimony have thus become ever more determined to keep their lawsuits in state courts where, naturally, plaintiff attorneys have fought every effort to adoptDaubert and Rule 702. The trial lawyers have inertia on their side; andDaubert’sreception has been particularly unfriendly in some of the most populous and influential states.”

Bernstein DE.Wall Street Journal. October 1, 2006

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2006-2133

2007;119;52

Pediatrics

St-André, Diane Francoeur and Anick Bérard

Ema Ferreira, Ana Maria Carceller, Claire Agogué, Brigitte Zoé Martin, Martin

Pregnancy in Term and Preterm Neonates

Effects of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Venlafaxine During

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/119/1/52 including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/119/1/52#BIBL This article cites 40 articles, 4 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

y_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/psychiatry_psycholog

Psychiatry/Psychology

sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/fetus:newborn_infant_

Fetus/Newborn Infant

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2006-2133

2007;119;52

Pediatrics

St-André, Diane Francoeur and Anick Bérard

Ema Ferreira, Ana Maria Carceller, Claire Agogué, Brigitte Zoé Martin, Martin

Pregnancy in Term and Preterm Neonates

Effects of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Venlafaxine During

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/119/1/52

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.