CHALLENGING CASES: DEVELOPMENTAL DELAY

A Child With a Learning Disability: Navigating School-Based Services*

CASE

Sam is a 7-year-, 10-month-old boy who was re-ferred to his pediatrician in March of his second grade for assessment because he is behind academi-cally, and his teacher wonders if he has attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Both parents came for the initial interview. No special assessments have been completed by the school except that the mother recalls that Sam was given a language screen-ing in kindergarten because he had trouble pro-nouncing the sound “r.” Sam was enrolled in a read-ing tutorread-ing program last year but has not received extra tutoring or supplemental school services this year. Sam has good gross motor skills and has many same-age friends. He has difficulty with handwrit-ing. He has always been considered compliant and good at following adult directions until this school year. Sam is considered noncompliant by his current teacher. He often fails to start or complete assign-ments that have been given to the class but has no aggressive or significant externalizing behaviors. Spelling, writing, and reading are considered to be below grade level by his teacher, but math skills are considered to be at grade level. Teacher and parental questionnaires and parental history were not sugges-tive of ADHD.

Sam lives with his parents and older sister. There is no family history of learning disabilities, ADHD, or psychiatric conditions. Both parents completed college and are employed outside the home. There have been no recent significant changes for the fam-ily. Birth history is unremarkable. Sam has had no loss of consciousness or episodes of otitis media. He has normal sleep and growth and no history of bed-wetting. Sam’s early development was considered typical except for slight articulation errors noted in kindergarten that resolved spontaneously. The screening test completed by the speech therapist at that time was informal, and no records were kept.

On examination, Sam is a cute, compliant child with a normal physical and neurological examina-tion except for mixed hand dominance and mild overflow movements. Sam’s height and weight are 50th percentile for his age. His conversation is typi-cal. When he was asked to read an easy Dr Seuss book, he frequently guessed at words and seemed to use the pictures as cues. He was clearly not a fluent reader. His pediatrician considered referring Sam to a psychologist for more comprehensive testing, but Sam’s parents worried about their ability to pay for such testing. Because Sam is having significant diffi-culty at school, Sam’s pediatrician wonders how she

can help Sam access evaluation and treatment ser-vices through his public school.

INDEX TERMS. learning disability, dyslexia, individual education plan.

Dr Martin T. Stein

Educators and pediatricians recognize the impor-tance of discovering a learning disability at an early age. Similar to most developmental conditions, early recognition leads to early intervention, which usu-ally has the potential for best outcome. A pediatri-cian who routinely asks specific screening questions for learning disabilities during health-supervision visits is likely to detect these neurologically based disorders in his or her patients. Sam’s pediatrician discovered a learning disability during an office as-sessment prompted by school underachievement and his teacher’s concern about the possibility of ADHD. She demonstrated excellent clinical skills by asking critical questions about his development, ed-ucational achievements and weaknesses, and family history. A focused neurodevelopmental examination and an office assessment of his reading level and fluency led to suspicion of a learning disability.

The real challenge for a pediatrician who suspects that a specific learning disability may be responsible for a child’s academic deficits is deciding what to do next. When a child psychologist is available in the community to evaluate the child with standardized tests for aptitude, achievement, a variety of learning disabilities, and mental health disorders, the referral process is simple and direct. However, access to psychoeducational testing is often hindered by finan-cial limitations of the family, lack of eligibility in most health care insurance plans, or the pediatri-cian’s lack of familiarity with available community resources.

Federal legislation during the last quarter of the 20th century has made a difference to kids like Sam. Public schools are required to develop an individual education plan (IEP) to provide a free, appropriate education in the least restrictive environment to chil-dren with learning disabilities. Once a learning dis-ability (or other developmental or behavioral condi-tion) is suspected, pediatricians must have a working knowledge of the procedures required by local schools for initiating a comprehensive evaluation. Guiding a parent in the right direction at this point is critical to a good outcome. It is not unlike the treat-ment for a common condition like streptococcal ton-sillitis; prescribing the correct antibiotic only begins the treatment. Specific directions about the use of an antibiotic are critical to a good outcome. Directing the parents of a child with a learning disability in the right direction begins the process of evaluation and treatment.

* Originally published inJ Dev Behav Pediatr.2001;22:188 –192. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-1721G

I askedDr Barbara Lounsburyto discuss the case of Sam from the perspective of a primary care pedi-atrician. Dr Lounsbury is a developmental and be-havioral pediatrician with an active community-based clinical practice. She is an especially strong advocate for her patients in working with public schools to ensure optimal services for children with developmental and behavioral conditions. She is also a fine teacher for educators, parents, and pediatric residents who want to learn about child advocacy in the schools.

Martin T. Stein, MD

Department of Pediatrics University of California San Diego, California

Dr Barbara Lounsbury

This child has characteristics that are typical of developmental dyslexia or a specific learning disabil-ity in the area of reading. Dyslexia is a chronic con-dition1 that is treated educationally, not medically.

The medical, family, and general educational aspects of dyslexia have been previously discussed in a prior Challenging Case and other recent publications2–4

and will not be addressed here. Children are often referred to the pediatrician in the hope that a medical condition and medical treatment can be found. An extensive medical evaluation is not usually neces-sary, but any evaluation can be guided by a detailed history. However, this child does need a comprehen-sive educational assessment.

Dyslexia serves as a useful example of the variety of learning disabilities and health conditions that can impact a child’s ability to function in an educational environment. An accurate description and diagnosis of learning disabilities takes time and money. Be-cause this child is having significant and persistent difficulty in school, it is appropriate to ask for an assessment by school specialists.

The federal law, outlined in the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act and its Amendments (IDEA), states that a “free appropriate public educa-tion is available for all children with disabilities be-tween the ages of 3 and 21, inclusive, including chil-dren with disabilities who have been suspended or expelled from school” (Table 1).5However, the

Na-tional Council on Disabilities, an independent fed-eral agency, in a recent report to Congress and the President documented widespread and persistent noncompliance with the regulations by local educa-tional agencies and found that “enforcement of the law is too often the burden of parents who must invoke formal complaint procedures . . . to obtain the services and supports to which their children are entitled under law.”5

The difficulties that many parents face in obtaining assessment and services for their children within our public education system make it critically important that pediatricians understand how to help parents. Pediatricians can play an important role as advocates for educational services for children with learning, emotional, or health conditions.

Information about special education procedures, including the full text of the IDEA amendments, is available from the US Department of Education.7

Each state’s department of education has additional information relevant to that particular state. The ini-tial assessment consists of procedures to “determine whether a child is a child with a disability and to determine the educational needs of such child.”5The

basic procedures are described below.

Step 1: Identification

All states are required to conduct “Child Find” activities to identify and evaluate all children with disabilities who need special education whether the children are in private, parochial, or public schools. When a child is identified as possibly needing special education and related services, a request for assess-ment can be made by the parent, school personnel, or other involved persons like a physician or psychol-ogist. The request can be made verbally or in writing. I recommend a dated letter addressed to the princi-pal of the local school and/or to the district’s director of special education. Parents should keep copies of all correspondence with the school. Below is a sam-ple letter from a physician requesting special educa-tion assessment.

Re: (student’s name and date of birth)

Dear (name of principal and/or special education director): I am requesting a full assessment of (child’s name) in all areas of this child’s suspected disabilities to determine whether he/she qualifies for special education services. (Enter names of specific areas of concern or particular tests you consider important to the evaluation). I understand that the parents will be given an assessment plan authoriz-ing this assessment within 15 days of your receipt of this request.

I am also requesting that an IEP meeting be held within the time required by law so that we may discuss the results of the assessment and the type of educational program this child requires. This child attends (name of school). You may call the parents at (phone number) if you have any questions regarding this request.

Sincerely, (Name and title)

Parental consent is needed before a child can be evaluated. I try to be very specific about any areas of need that I think should be addressed. I routinely request tests such as the Gray Oral Reading Test-3, Test of Written Language-3, and the Children’s Handwriting Evaluation Scale if I am not completing these tests myself. Parents should keep copies of any correspondence, formal and informal, with the school. I recommend that they use a loose-leaf note-book to help keep these records in chronological order.

Some schools would recommend a Student Study Team (SST) or similar group meeting before consid-ering an assessment for special education. An SST

TABLE 1. Six Principles of IDEA 1. Free appropriate public education 2. Appropriate evaluation

3. Individualized education program 4. Least restrictive environment

meeting is not a substitute for the special education assessment process. It can be appropriate as a quick look and as a means of planning for children who are presenting with their first school difficulty. Sam is already near the end of second grade, has significant difficulty reading, and has failed less formal inter-ventions. Even special education assessment and placement will take 2 to 3 months to complete, so an SST meeting is not an appropriate intervention if it slows down formal assessment and placement plan-ning.

There are some children who we know are at high risk for persistent and significant problems in school but who have not fallen far enough behind to meet the formal criteria for a disabling condition under IDEA. Children with dyslexia may fall into this cat-egory because we can often predict the children who are going to have school difficulties at a young age, yet there may not be a significant discrepancy be-tween achievement and intelligence, which is re-quired to classify a student as learning-disabled. A parent or physician may need to ask for reassessment if school difficulties persist or worsen. Consider also that many of our patients have dual diagnoses and may qualify for and need services because of other health impairments such as ADHD, asthma, or anx-iety disorders.

Step 2: Evaluation

After a written request is made by parents or oth-ers and then received by the school, the school has 15 days to give the parents an assessment or evaluation plan that indicates the areas to be assessed and usu-ally describes specific tests to be administered. Dis-tricts vary in the comprehensiveness of their initial assessments. At a minimum, districts will assess ac-ademic achievement and cognition. It is appropriate for a pediatrician or other specialist to ask for assess-ment in other potential areas of need such as lan-guage, motor, sensory processing, social/emotional, and health. I put specific requests, when applicable, in my assessment request.

The parent reviews, modifies (if necessary), and signs the evaluation plan and returns it to the school as quickly as possible. The school then has 50 days (with extensions for long school holidays) to com-plete the testing and hold a team meeting to go over the child’s evaluation results and decide whether the “child is a child with a disability” as defined by IDEA.

Step 3: Determination of Eligibility

The team meets to determine if the child is a child with a disability and whether special education ser-vices are needed. Parents should not sign special education documents they do not agree with. Federal and state laws outline procedures for handling dis-agreements between schools and parents in areas such as eligibility, placement, and level of service. Parents or schools can request mediation or proce-dural due process to challenge team decisions.

Step 4: Writing the IEP

If the child is found to be eligible for special edu-cation and related services, the IEP team must meet again within 30 days to write the IEP. Parents and, when appropriate, the student are part of the IEP team. Services are to be provided “as soon as possi-ble after the meeting.” The IEP document contains a great deal of useful information about a child. The IEP document must include all of the following in-formation: current levels of performance, annual goals with interim short-term objectives, measurable goals, a list of the specific services provided to the child (eg, supplementary aids, speech therapy, adap-tive physical education, classroom modifications, staff training, or supports), extent of participation with nondisabled children, transition service needs, and how progress will be measured. An IEP must also state when services begin, where and how often they will be provided, and how long services will continue. Transportation is routinely provided by districts, and many children qualify for extended-year programs.

Step 5: IEP Reviews

The specifics of the IEP are required to be re-viewed once a year. Parents or the school can request a review of the IEP at any time, and a meeting must be held within 30 days of a written request for a review. A major review, usually including retesting in the areas of concern, must be held every 3 years but may be done more frequently if needed. Al-though the criteria for qualifying for special educa-tion are fairly specific, there are no specific criteria for exiting special education services. At times, a parent may be told that the child no longer qualifies for special education services, but this may not be correct. Decisions to end special education services must be carefully examined.

Accessing special education services is really just the first step in getting appropriate help for a child like Sam. Educational programs, like medical treat-ments, need to be monitored for effectiveness. The findings of research in the educational treatment of learning disabilities is starting to become available, and these findings may help us understand which educational interventions are likely to be effective.8

Pediatricians can help a child like Sam by monitoring reading on a regular basis. I use the Gray Oral Read-ing Test-3,9 which looks at reading rate, accuracy,

and comprehension, but this test is too long for most pediatricians. General pediatricians might consider the Einstein Assessment of School-Related Skills,10

which is a quick screening test for grade-level per-formance from kindergarten to fifth grade. Pediatri-cians can also help parents by referring them to national and local advocacy and educational organi-zations.

The major national organizations are listed below:

• International Dyslexia Society: www.interdys.org; tel: 800-ABCD123

• National Center for Learning Disabilities: www. ncld.org; tel: 212-545-7510

• National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health: www.ninds. nih.gov

Barbara Lounsbury, MD

Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics San Diego, California

REFERENCES

1. Shaywitz S, Fletcher J, Holahan J, et al. Persistence of dyslexia: the Connecticut Longitudinal Study at Adolescence.Pediatrics.1999;104: 1351–1359

2. Stein M, Zentall S, Shaywitz S, Shaywitz B. Challenging case: a school-aged child with delayed reading skills.J Dev Behav Pediatr.1999;20: 381–385

3. Shaywitz S. Dyslexia.N Engl J Med.1998;338:307–312

4. Gottesman R, Kelly M. Helping children with learning disabilities to-ward a brighter adulthood.Contemp Pediatr.2000;17:42– 61

5. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Amendments of 1997. Available at: www.ed.gov/offices/OSERS/Policy/IDEA/index.html. Accessed 2001

6. National Council on Disability. Back to School on Civil Rights: report to the President of the United States, January 25, 2000

7. Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services, US Department of Education: a guide to the individualized education program, July 2000. Available at: www.ed.gov/parents/needs/speced/iepguide/ index.html. Accessed 2001

8. Swanson H. Reading research for students with LD: a meta-analysis of intervention outcomes.J Learn Disabil.1999;32:504 –532

9. Wiederholt J, Bryant B.Gray Oral Reading Test-3. Austin, TX: Pre-ED; 1992

10. Gottesman R, Cerullo F.Einstein Assessment of School-Related Skills. New York, NY: Distributed by Albert Einstein School of Medicine; 1988

Web Site Discussion

The case summary for the Challenging Case was posted on the Developmental and Behavioral Pedi-atrics web site‡ (www.dbpeds.org.list) and the

Jour-nal’s web site (www.lww.com/DBP). Comments

were solicited.

Morris Wessel, MD

Even when school systems know the “law,” they often have a backlog and lag behind. I have found that consistent support for parents, occasionally with a phone call or a visit to the school guidance person or principal, often moves work-ups along. It only took me 25 years to establish this reaction that seems to speed up school services when the parents men-tion my name. So, those of my colleagues who are younger, I urge you to keep at it. I don’t mean to imply that all schools respond quickly, but it is far easier to speed up appropriate studies than it was 25 years ago. Please don’t give up!

Anna Baumgaertel, MD

This is a very typical case in a pediatric practice. A request by the parents for psychoeducational testing

needs to be submitted in writing to the school (prin-cipal or teacher). It helps to include the report of the pediatric developmental evaluation with the recom-mendations for testing. The schools usually lag far behind with their testing schedules, so, as with other things, “the squeaky wheel gets the grease,” and I encourage my parents to squeak!

After the testing there should be a multidisci-plinary meeting with the psychologist, teacher, and other relevant persons to decide on interventions, modifications, etc. I usually have the parents return to my office after the testing and multidisciplinary team meeting to discuss the results and interven-tions. We have handouts with treatment recommen-dations for various school-related problems. Per-sonal phone calls with school personnel are usually very helpful in getting the full picture.

I think it is also very important to encourage the parents to be aware of and support their child’s extracurricular interests and abilities as a source of nonacademic competence-building and self-esteem.

Frank Aiello III, MD

Nice case. I wish I saw cases this straightforward in my practice. Sam presents a clinical picture that is consistent with dyslexia (possibly with dysgraphia) or specific learning disability in reading (possibly also writing). The history of articulation problems and mixed dominance are known risk factors for reading disorder/disability. Did he have an inordi-nate degree of difficulty learning the letter names? Is he struggling with phonics? (I suspect “yes” to both of these.) The behavior problems appear to be sec-ondary to the learning difficulty and not a primary, intrinsic problem for Sam.

The approach that the school has taken so far is, in my experience, sadly typical. Sam requires psycho-educational testing to identify his learning strengths and weaknesses and to determine his learning dis-ability. Beyond the “Weschler Intelligence Scale for Children, Third Edition . . . Woodcock-Johnson” bat-tery of tests, an extensive assessment of reading, including assessment of phonological processing, is likely to be necessary (although this is not done by the schools in my locale). This extended reading assessment is necessary as, in my experience, chil-dren in the first few grades of elementary school with significant reading disability can be missed by the typical IQ-achievement formula used. This is noted when the achievement measure is the Woodcock or other measures that can be falsely elevated by sight-word recognition.

I have found that often a letter from the physician requesting comprehensive psychoeducational as-sessment addressed to the school principal will help to obtain this assessment.

Dr Martin T. Stein

The early recognition and initial evaluation of learning disabilities by primary care pediatricians is often difficult, I suspect, because of the lack of a clear definition. The educational, psychological, and neu-rological literature often use different (and conflict-ing) definitions of learning disability. A definition

developed by the National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities in 1990 is useful:

Learning disabilities is a generic term that refers to a hetero-geneous group of disorders manifested by significant diffi-culties in the acquisition and use of listening, speaking, re-ading, writing, reasoning, or mathematical abilities. These disorders are intrinsic to the individual, presumed to be due to central nervous system dysfunction, and may occur across the life span. Problems in self-regulatory behaviors, social perception, and social interaction may exist with learning disabilities, but do not by themselves constitute a learning disability.1

Clinicians divide learning disabilities into at least 4 domains of function: dyslexia (a language-based dis-order of learning associated with difficulties in sin-gle-word decoding; these children have difficulty reading and spelling as a result of a disorder in processing of small units sound known as pho-nemes); dyscalculia (a disorder of mathematics asso-ciated with a deficiency in visual-spatial skills or a difficulty with arithmetic fact retrieval or with the use of mathematical procedures); dysgraphia (a problem with fine motor and visual-motor coordina-tion associated with messy handwriting, distorted shapes, and poorly structured drawings); and prag-matic language disorders (a distortion of the nonver-bal aspects of language used in a social context).

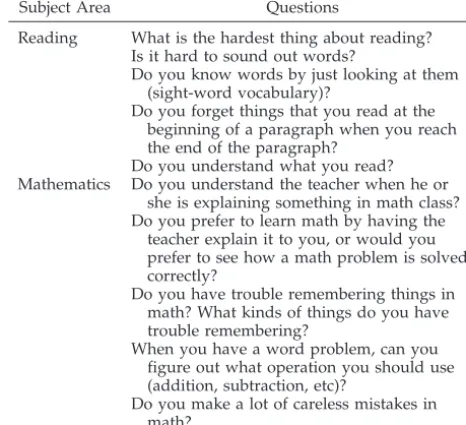

A recent, excellent review of disorders of learning and school failure was written for pediatricians in a primary care practice.2It is a useful guide to early

recognition during health-supervision visits. The au-thor provides a set of lucid questions directed to the child to help the physician assess reading and math-ematics problems in learning (Table 2). When incor-porated into health-supervision visits beginning in the first grade, I have found these questions to be a valuable tool in understanding an individual child’s learning style.

In addition, the quality of information obtained in a clinical setting is dependent on not only what we ask but also how it is asked. The Parent’s Evaluation of Developmental Status screening instrument for

developmental and behavioral problems emphasizes the importance of the language we use when we ask parents about their child’s development, as seen in these questions: “Do you have any concerns about how your child is learning to do things for himself/ herself?” and “Do you have any concerns about how your child is learning preschool or school skills?”3

REFERENCES

1. Hammill DD. On defining learning disabilities: an emerging consensus. J Learn Disabil.1990;21:74 – 84

2. Lindsay RL. School failure/disorders of learning. In: Bergman AB, ed.20 Common Problems in Pediatrics. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001: 319 –336

3. Glascoe FP.Parent’s Evaluation of Developmental Status. Nashville, TN: Ellsworth and Vandermeer Press Ltd; 1997

TABLE 2. Interview Questions Regarding Academic Perfor-mance

Subject Area Questions

Reading What is the hardest thing about reading? Is it hard to sound out words?

Do you know words by just looking at them (sight-word vocabulary)?

Do you forget things that you read at the beginning of a paragraph when you reach the end of the paragraph?

Do you understand what you read? Mathematics Do you understand the teacher when he or

she is explaining something in math class? Do you prefer to learn math by having the

teacher explain it to you, or would you prefer to see how a math problem is solved correctly?

Do you have trouble remembering things in math? What kinds of things do you have trouble remembering?

When you have a word problem, can you figure out what operation you should use (addition, subtraction, etc)?

Do you make a lot of careless mistakes in math?

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2004-1721G

2004;114;1432

Pediatrics

A Child With a Learning Disability: Navigating School-Based Services

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/114/Supplement_6/1432

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

#BIBL

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/114/Supplement_6/1432

This article cites 6 articles, 1 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

rning_disorders_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/cognition:language:lea

Cognition/Language/Learning Disorders

al_issues_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/development:behavior

Developmental/Behavioral Pediatrics

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2004-1721G

2004;114;1432

Pediatrics

A Child With a Learning Disability: Navigating School-Based Services

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/114/Supplement_6/1432

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.