Infant Sleep Position in Licensed Child Care Centers

Naomi B. Gershon*‡; and Rachel Y. Moon, MD*

ABSTRACT. Objective. To determine 1) familiarity of child care centers with American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommendations regarding infant sleep position, 2) predominant infant sleep positions in child care set-tings, and 3) child care policies pertaining to sleep posi-tion for infants less than 6 months of age.

Design. A descriptive, cross-sectional telephone sur-vey including the age and number of infants cared for, infant sleep positions currently in use, and details re-garding reasons for sleep position policies.

Participants. All licensed child care centers caring for infants less than 6 months of age in Washington, DC, and Montgomery and Prince Georges Counties in Maryland. Results. Out of 137 centers in these areas that accept infants less than 6 months of age, 131 completed the survey. Only 57% (75) of the centers were aware of rec-ommendations regarding infant sleep position. Infants were placed prone in 49% (64) of the centers and 20% (26) of the centers positioned infants exclusively in the prone position. Of the centers, 75% (98) did not have a written policy regarding sleep position. Most common reasons for placing infants in the prone position included child comfort, fear of choking, and guidance by the parents of the infants. Centers that used the prone position exclu-sively cared for significantly fewer infants on average than centers that never or only sometimes placed infants prone.

Conclusions. Almost half (43%) of licensed child care centers surveyed in the greater Washington, DC area were unaware of the association between sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and infant sleep posi-tion. Child care centers aware of prone positioning as a SIDS risk were less likely to place infants to sleep in this position, with many such centers avoiding prone positioning entirely. However, it was common for cen-ters aware of the SIDS risk to still place infants prone if directed to do so by parents or if concerned about child comfort. Further educational efforts directed to-ward child care providers are needed.Pediatrics 1997; 100:75–78;sleep position, sudden infant death syndrome, child care.

ABBREVIATIONS. SIDS, sudden infant death syndrome; AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; SD, standard deviation.

T

he identification of an association betweenprone infant sleep position and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)1– 4led to a 1992 recom-mendation by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) to place all healthy infants in the supine or lateral position for sleep.5Encouragement by health professionals, the media, and health promotional ac-tivities have helped reduce the percentage of US parents placing infants prone from 70% in 1992 to 29% in 1995.6It is yet unclear how child care centers position infants for sleep. A search of the literature revealed no previous studies of SIDS risk factors in organized child care facilities, and information on recent SIDS rates in child care was available for only two US states, Minnesota and California.7,8Currently no regulations exist for the District of Columbia or Maryland child care centers pertaining to sleep po-sition,9,10 and American Public Health Association and AAP recommendations concerning safety in child care centers (published in the same year as the 1992 recommendations concerning sleep position) make no direct mention of infant sleep position.11

According to the US Census Bureau, in 1993 (the most recent year for which data exists), 17% of US infants under 1 year of age were attending some type of organized child care, 8% in child care centers, and 9% in family day care homes (nonrelatives).12,13Data from Minnesota suggests that the percentage of SIDS deaths occurring in organized child care may be as high as 35.4%.7Furthermore, statistics from Califor-nia8 indicate that over 40% of SIDS deaths in that state occur in child care settings.aThere is no reason

to believe that child care attendance rates in Minne-sota are substantially different from the US as a whole, and child care attendance rates in California are below the national average (Lynne Casper, Mar-tin O’Connell, US Census Bureau, personal commu-nication, May 1996). Although data concerning child care deaths is not available at a national level,14 it seems that, in at least 2 states, more than one third of SIDS deaths occur while infants are in organized child care, even though infants attending organized child care represent only 17% of all US infants. Why such a disproportionate number of SIDS deaths oc-cur in child care is unknown, but given that prone sleeping is recognized as an important preventable risk factor, it is worthwhile to examine the preva-lence of prone infant sleep positioning in child care centers, and the centers’ stated motivations for sleep

From the *Department of General Pediatrics, Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC; and the ‡Department of Paediatrics, Monash University Faculty of Medicine, Melbourne, Australia.

Received for publication Sep 9, 1996; accepted Nov 7, 1996.

Reprint requests to (R.Y.M.) Department of General Pediatrics, Children’s National Medical Center, 111 Michigan Ave, NW, Washington, DC 20010. PEDIATRICS (ISSN 0031 4005). Copyright © 1997 by the American Acad-emy of Pediatrics.

aPlease note that more detailed information on what constitutes a “child

position choices. Analysis of infant positioning in child care is also important as it may be a potential confounder in other studies of infant sleep position-ing.

The objectives of this study were:

1. To determine the existence of policies, if any, at licensed child care centers governing infant sleep position;

2. To determine the prevalence of prone infant sleep positioning in child care settings;

3. To identify reasons for choice of infant sleep po-sition in child care settings; and

4. To evaluate these findings in view of the 1992 AAP recommendations regarding infant sleep po-sition.

METHODS

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC. Lists of government licensed child care centers were provided by the Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs Service Facility Regulation Administration in Washington, DC, Child Care Con-nection (list of licensed centers in Montgomery County, MD), and the Prince Georges Child Care Resource Center (list of licensed centers in Prince Georges County, MD). Centers that cared for infants less than 6 months of age were then telephoned in May 1996 and asked to participate. Telephone calls were directed to a care giver or supervisor familiar with care of the infants at each center. Inquiries were then made regarding the total number of children cared for by the center, the number of children less than 6 months of age currently in care, an estimate of the percentage of time infants currently spend sleeping on their sides, backs, and stomachs, details concerning any sleep position policies, and awareness of recommendations about infant sleep position. Ques-tions concerning motivaQues-tions for choice of infant sleep position were open-ended, and multiple reasons from each center were noted. At the end of the interview, centers unaware of any risk in the prone position were provided with information regarding the AAP recommendations on sleep position. Data were analyzed via univariate analysis.

RESULTS

All 137 listed licensed centers in the three jurisdic-tions were contacted; 58 centers were located in Washington, DC, 51 in Montgomery County, and 28 in Prince Georges County. A total of 131 centers agreed to participate in the study, for a participation rate of 96%. Six centers (4%) did not participate, one declining because of lack of interest and five centers failing to answer numerous telephone calls. A total of 391 infants under six months of age were in atten-dance at these centers at the time of survey. Infants less than 6 months of age averaged only 7.8% of the total number of children at the surveyed centers. The average total number of children at each center was 61.6 (standard deviation [SD] 44.6), with a range of 5 to 214 children. The number of infants less than 6 months of age at each center ranged from 0 to 18 infants, with a mean of 2.98 (SD 2.96) infants. Licens-ing regulations in WashLicens-ington, DC and Maryland stipulate maximum infant-provider ratios of 4:1 and 3:1 respectively, with a maximum number of infants per group of 8 and 6.

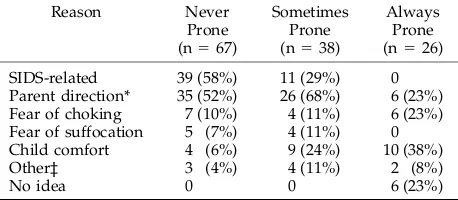

Infants were placed prone at least some of the time in 49% (64) of surveyed child care centers, with 20% (26) doing so all of the time (Table 1). Reasons for doing so varied (Table 2). Of the centers that placed

infants prone exclusively, 38% were likely to do so for reasons of child comfort, stating that infants sleep better that way. Other frequently cited reasons for placing infants exclusively prone were fear of chok-ing (23%), and guidance by the parents of the infants (23%). Two centers placed infants prone if they were frequently congested for better fluid drainage. Ap-proximately 20% of the centers placing infants prone had no idea why they did so. Thirty-one percent of the centers offered more than one reason motivating their center’s choice of infant sleep position.

Of the 67 centers claiming never to place infants prone, most did so because of direction from the parents (52%) and/or because of SIDS-related recom-mendations (58%) (Table 2). Other reasons for avoid-ing prone positionavoid-ing entirely included the concern that infants might choke or suffocate while prone. Thirty-eight centers (29%) placed infants prone some of the time, or placed some, but not all, infants prone. These centers almost always did so either because of parental insistence (68%) or to encourage certain in-fants, who were thought to sleep better in the tummy position, to sleep (24%).

Thirty-three centers (25%) had a written policy regarding sleep position. Of these, 19 centers never placed infants prone, 12 centers would only do so occasionally (if requested by parents), and 2 centers claimed to have a policy to always place infants on their stomachs. Centers that had heard of the AAP recommendations were more likely to have a written policy (x2 5 10.9; P , .0001). Two centers recom-mended side or back sleep positions to parents in the form of a newsletter.

At the end of the survey, after reporting their motivations for, and choice of, sleep position, 57% (75) of the centers claimed to have heard of recom-mendations about infant sleep position. Yet only 35% (46) of the centers had cited SIDS-related reasons earlier in the interview as a motivation for their

TABLE 1. Rates of Infant Positioning in the Centers Studied (n5131)

Position Always (%) Sometimes (%) Never (%)

Prone 26 (20%) 38 (29%) 67 (51%)

Supine 19 (15%) 49 (37%) 63 (48%)

Lateral 24 (18%) 52 (40%) 55 (42%)

TABLE 2. Reasons for Infant Positioning by Positioning Used

Reason Never

Prone (n567)

Sometimes Prone (n538)

Always Prone (n526)

SIDS-related 39 (58%) 11 (29%) 0 Parent direction* 35 (52%) 26 (68%) 6 (23%) Fear of choking 7 (10%) 4 (11%) 6 (23%) Fear of suffocation 5 (7%) 4 (11%) 0 Child comfort 4 (6%) 9 (24%) 10 (38%)

Other‡ 3 (4%) 4 (11%) 2 (8%)

No idea 0 0 6 (23%)

* Parent direction includes both verbal direction and (in many centers) parental choice of sleep positioning on an intake ques-tionnaire.

‡ Other reasons included: caregiver’s experience with own child, fear that child might inhale chemicals, gastric problems, promo-tion of better fluid drainage, and prevenpromo-tion of hair loss.

decisions about sleep position. Centers reporting SIDS-related reasons as motivation for choice of sleep position were significantly more likely to al-ways use the supine or side positions than those reporting other reasons (P , .0001). However, 26 centers aware of the recommendations continued to place infants prone. Forty-eight percent of the centers aware of the recommendations were still willing to use prone positioning if directed to do so by the infants’ parents, and 23% did so for reasons of child comfort. In addition, 3 centers incorrectly believed that nonprone positioning was only important until the age of 3 months, after which infants were switched to their stomachs for sleep because care givers believed they slept better that way. For centers choosing a sleep position based on SIDS-related rea-sons, sources of information included advice from center’s pediatrician, a health consultant, a govern-ment health departgovern-ment, training classes for child care providers, and the media.

Many centers (13%) were concerned about infants choking while on their backs. Twenty-two percent of the 63 centers that never used the supine position cited choking as a reason.

The total number of children per center was not significantly associated with either choice of prone positioning (P 5 .1725) or with citation of SIDS-related reasons for choice of infant sleep position (P5 .7862). However, there was an association be-tween number of infants less than 6 months of age in the center and prone positioning. Centers always placing infants prone had, on average, 1.65 (SD 2.21) infants in their care. This was significantly fewer infants than centers that never (P , .05) or some-times (P, .01) placed infants prone. These centers had a mean of 3.13 (SD 3.04) and 3.63 (SD 3.04) infants, respectively. Perhaps centers caring for fewer infants had less exposure to current recom-mendations concerning infant sleep positioning than did centers with many infants in the relevant age group.

DISCUSSION

This study found that a surprisingly low number (57%) of child care centers were aware of AAP rec-ommendations on sleep positions, and only 51% were fully compliant with the recommendations. In 18% of the child care centers surveyed, infant care providers were willing to choose a sleep position for the infants in their care based on child comfort. Per-haps this is not surprising, as these providers could be caring for up to four crying infants at a time. Indeed, studies of sleep position have identified longer, quieter sleep for infants sleeping prone,15,16 and prone sleeping has been associated with higher arousal thresholds to environmental noises.17 How-ever, it is also acknowledged that the deeper sleep experienced by prone infants may itself be a factor in SIDS.18 It may be necessary for authorities advising child care centers on SIDS risk factors to acknowl-edge that infants may not sleep as well on their backs or sides, but that lateral or supine positioning is still safer.

Fear of infants choking in the supine position

re-mains a common concern in the US, and was cited as the reason for never placing infants supine by 22% of the centers in this study. The side position is often recommended in the US as a safe alternative to prone positioning, as infants are assumed to be less likely to choke. However, the side position is unstable, with 10% to 15% of infants rolling to their stomachs.19 Although gastroesophageal reflux is increased in the back position and there is some evidence that reflux can cause life-threatening events,20,21recent interven-tions encouraging nonprone infant positioning in Australia and England have not been accompanied by any increase in the incidence of lethal aspira-tion.22–24

Many child care centers aware of the SIDS risk succumbed to parental insistence that infants be placed in the manner they are accustomed to. This is clearly a difficult situation for child care centers, and some centers have attempted to resolve this with the use of written policies.

Only 51% of the centers in this study were in full compliance with AAP recommendations on sleep position. This rate can be compared with the compli-ance rate of child care centers nationwide with Na-tional Health and Safety Performance Standards as published by the AAP and the American Public Health Association. A survey of 2003 child care di-rectors found that compliance with 16 guidelines (not including sleep position) ranged considerably from 19.5% to 98.6%, with many centers falling short of desired infant protection.25

Like any survey, the validity of these results is limited by the accuracy of the participants’ answers. Questions were phrased in a manner designed to encourage truthful responses, but it is acknowledged that centers aware of the recommendations may have been unwilling to reveal actual sleep positions. This study found that many child care centers were unaware of the association between infant sleep positioning and SIDS, and few centers had policies regarding sleep position. It is evident from this study that further efforts at increasing the awareness of importance of proper infant positioning are needed. These efforts must be directed at both parents and child care providers if they are to be effective.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Lynne Casper and Martin O’Connell of the US Census Bureau, Patrick Carolan, MD, medical director of the Minnesota SIDS Center, and Marcia Noonan of the California Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Program, for providing and ex-plaining information regarding US and state statistics. Our thanks also go to Ethan Gershon for statistical analysis and assistance in writing, and to Peter C. Scheidt, MD, MPH; Tina L. Cheng, MD, MPH; Benjamin Gitterman, MD; and Steven L. Zeichner, MD, PhD, for their thoughtful comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Dwyer T, Posonby A-L, Newman NM, Gibbons LE. Prospective cohort study of prone sleeping position and sudden infant death syndrome. Lancet. 1991;337:1244 –1247

2. Taylor BJ. A review of epidemiological studies of sudden infant death syndrome in Southern New Zealand. J Paediatr Child Health. 1991;27: 344 –348

4. Hoffman HJ, Hillman LS. Epidemiology of the sudden infant death syndrome: maternal, neonatal and postneonatal risk factors. Clin Peri-natol. 1992;19:717–737

5. AAP Task Force on Infant Positioning and SIDS. Positioning and SIDS. Pediatrics. 1992;89:1120 –1126

6. Bak SM, Willinger M, Hoffman HJ, et al. Infant sleep practices: results from US national surveys 1992–1995. Presented at the Fourth SIDS International Conference; June 23–26, 1996; Bethesda, MD. (Abstract 1–27– 01)

7. Carolan PL. SIDS in Minnesota: A Summary of 1994 Statistics. Minneap-olis, MN: The Minnesota SIDS Center; 1995

8. Noonan M. Professional Health Education. Presented at the Fourth SIDS International Conference; June 23–26, 1996; Bethesda, MD. (Abstract 3–14 – 01)

9. Code of District of Columbia Regulations. DCMR 29 Public Welfare. Wash-ington, DC: Office of Documents; May 1987

10. Department of Human Resources, State of Maryland. Code of Maryland Regulations 97.04.02–Family Law Article, Title 5, Subtitle 5, Part VII–Child Care Center Licensing. May 1994

11. American Public Health Association and American Academy of Pedi-atrics. Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards: Guidelines for Out-of-Home Child Care Programs. 1992 12. Casper LM. Who’s minding our preschoolers? Current Population

Re-ports, Census Bureau. March 1996;P70 –53:1–7

13. US Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. Statistical Abstract of the United States, Fall 1994. 1995

14. Good SEE, Parrish RG, Ing RT. Children’s deaths at day-care facilities. Pediatrics. 1994;94(suppl):1039 –1041

15. Brackbill Y, Douthitt TC, West H. Psychophysiologic effects in the

neonate of prone versus supine placement. J Pediatr. 1973;82:82– 84 16. Kahn A, Groswasser J, Sottiaux M, Rebuffat E, Franco P, Dramaix M.

Prone or supine body position and sleep characteristics in infants. Pediatrics. 1993;91:1112–1115

17. Franco P, Pardou A, Hainaut M, Gorswasser J, Kahn A. Prone body position: sleep characteristics and reactivity to auditory stimulations in healthy infants. Presented at the Fourth SIDS International Conference; June 23–26, 1996; Bethesda, MD. (Abstract 3–25– 06)

18. McKenna JJ, Fleming PJ. Ethnicity and the sudden infant death syndrome: important clues from anthropology. Arch Dis Child. 1994;70: 450. Letter

19. Gibson E, Cullen JA, Spinner S, Rankin K, Spitzer A. Infant sleep position following new AAP guidelines. Pediatrics. 1995;96:69 –72 20. Blumenthal I, Lealman LL. Effect of posture on gastro-oesophageal

reflux in the newborn. Arch Dis Child. 1982;57:555–556

21. Jolley S, Halpern L, Tunnell W, Johnson D, Sterling C. The risk of sudden infant death from gastro-oesophageal reflux. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26:691– 696

22. Beal S, Porter C. Sudden infant death syndrome related to climate. Acta Paediatr. 1991;80:278 –287

23. Wigfield R, Fleming PJ, Berry PJ, Rudd PT, Golding J. Can the fall in Avon’s sudden infant death rate be explained by changes in sleeping position? Br Med J. 1992;3034:282–283

24. Engelberts AC, deJonge GA, Kostense PJ. An analysis of trends in the incidence of sudden infant death syndrome in the Netherlands 1969 – 89. J Paediatr Child Health. 1991;27:329 –333

25. Addiss DG, Sacks JJ, Kresnow M, O’Neil J, Ryan GW. The compliance of licensed US child care centers with national health and safety per-formance standards. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1161–1164

TOO MUCH TV

Now that we are thinking about the V-chip, we should also think about the T-chip—a time chip—to make sure that we aren’t simply rearranging the content problem into a viewing problem [for children]. Past a certain point, after all, the only solution is to turn the damn thing off.

Gladwell M. Chip thrills. New Yorker Magazine. January 20, 1997.

Submitted by Student

DOI: 10.1542/peds.100.1.75

1997;100;75

Pediatrics

Naomi B. Gershon and Rachel Y. Moon

Infant Sleep Position in Licensed Child Care Centers

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/100/1/75

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/100/1/75#BIBL

This article cites 16 articles, 6 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/fetus:newborn_infant_ Fetus/Newborn Infant

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.100.1.75

1997;100;75

Pediatrics

Naomi B. Gershon and Rachel Y. Moon

Infant Sleep Position in Licensed Child Care Centers

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/100/1/75

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.

the American Academy of Pediatrics, 345 Park Avenue, Itasca, Illinois, 60143. Copyright © 1997 has been published continuously since 1948. Pediatrics is owned, published, and trademarked by Pediatrics is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly publication, it

at Viet Nam:AAP Sponsored on August 30, 2020

www.aappublications.org/news