Medical students’ action plans are not specific

Jo Hart1, Lucie Byrne-Davis2, Val Wass3, Chris Harrison4

Attribution of work: Division of Medical Education, University of Manchester

1 (Corresponding author). Division of Medical Education, School of Medical Sciences, University of Manchester, Oxford Rd, Manchester M13 9PT. jo.hart@manchester.ac.uk +44 (0) 161 275 1845

2Division of Medical Education, University of Manchester. 3 School of Medicine, Keele University

4 School of Medicine, Keele University

Structured summary

Background: Action plans have been shown to be important in changing behaviour. In learners, action plans have been proposed as a mechanism by which feedback leads to increase in expertise, with feedback leading to action plans, leading to changes in learning behaviours, leading to improvement. However, little is known about the extent that students are able to make specific actions plans that relate to the feedback they are given.

Results: 185/196 (94%) of students made one or more action plans but only 31/196 (16%) made one or more action plans that were directly related to the feedback given to them.

Discussion: Whilst educators may include action planning in education; students are not making specific enough action plans to affect change. Future work should

Background

The importance of making plans in changing behaviour has been well established. Creating specific plans about action e.g., implementation intentions, is associated with increased behaviour change [1]. In education, the setting of concrete and specific goals is reported as crucial to skill development in response to feedback [2]. Feedback is an accepted part of teaching and learning, seen by many as the key foundation of effective learning in health professional education and potential power in learning is well-established [3]. In medical education, feedback does not invariably

lead to improvement but that those receiving feedback improve their communication skills more than those who aren’t given feedback [4]. The mechanisms of action planning in feedback are not fully understood.

Action plans are recommended within medical education [5] as part of feedback but recent studies have shown that action plans in medical training are rare [6,7].

Findings to date have focused on the amount and quality of action plans, but not on the way in which the action plans relate to feedback provided; and which learners are more or less likely to make action plans.

We wanted to understand how much specific action planning students undertook after feedback in a communication skills session in a year 1 medical student cohort. Communication skills education is an important area to investigate because

1. What action planning do students undertake after being given feedback and being directed to make an action plan?

2. Are action plans made specific and do they relate to the feedback given?

Methods

Design: We collected data from a formative objective structured clinical examination (OSCE). A formative OSCE is performed with the purpose of giving feedback to the student.

Participants and context: Participants were first year undergraduate medical students at a UK medical school (cohort size 363) on a 5-year PBL programme. Students were recruited for the study when attending a scheduled class. They were able to attend the class/receive feedback without their data being used for research.

Materials:

Communication scoring sheet: Students were given quantitative/free text feedback from peers, simulated patients (SPs) and tutors using a communication assessment tool [8], response scale 0 (omits almost all skills) to 3 (uses virtually all skills) in 5 areas – 1. Opening the interview, 2. Gathering an account of the story/symptoms, 3. Obtaining the person/patient’s thoughts and any concerns; responding appropriately, 4. Building and maintaining the relationship 5. Maintaining structure in the

SP scenarios: 4 different scenarios were used. All had been previously piloted, and were judged as being of similar difficulty by the communication teaching team. For examples of scenarios, see Harrison, Hart, Wass [8].

Feedback and action plan forms: Students were provided with sheets that had space for them to complete with feedback from colleagues/SPs about what they had done well, and what they could improve on. There was also a box for making action plans, and a reminder of how to make a specific action plan.

Procedure:

Communication teaching session (formative OSCE): Groups of 3 students took part in OSCE communication stations with SPs. Each student carried out one five-minute communication scenario with an SP; and was then marked on the station by the SP and the two student colleagues. They then had 10 mins for feedback and discussion. Student observers were asked to provide both positive (things they had done well) and constructive (things to do differently) feedback, and mark the student. All students had previously had experience of giving and receiving communication feedback. During this time, students wrote down the verbal feedback they had been given as well as the scores.

Students then developed action plans, and given information about how to make an action plan. They were reminded to make the plans specific and achievable.

Consent: Ethics permission was given by the University ethics committee.

Students attending the communication session were asked if they would like their data to be used for research purposes. Those students who didn’t consent to the analysis of their results took part in the session in exactly the same way as those who did consent and their data was not collected by the researcher.

Coding and Analysis: Formative and summative scores were entered, with student ID number, into SPSS version 20.0.

Coding of feedback:

o Feedback coded into the 5 areas of communication that they had been scored on

o Whether feedback was positive or constructive (suggestions for improvement).

Coding of action plans:

o Action plans were coded using two categories: phase of communication and degree of specificity. Specific was defined as structured to include one or more of the SMART goal components (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, timely)

o Each action plan was coded by two authors, who reached a high level of agreement (kappa 0.91).

Calculations:

Results

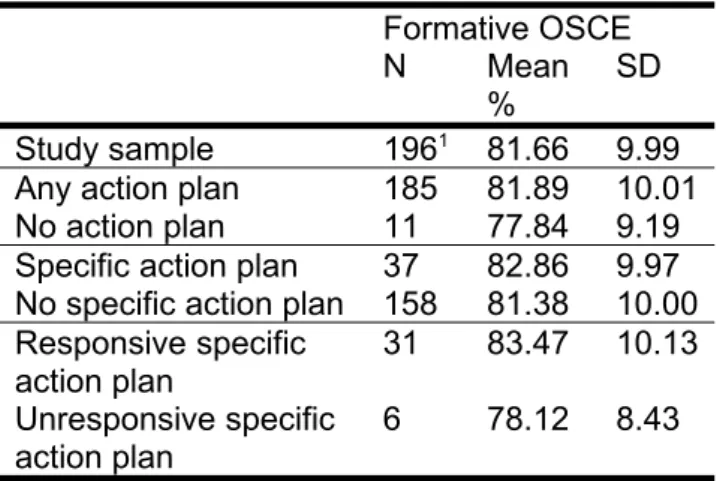

196 /363 (54% of the cohort) students took part, recorded their scores and feedback and agreed to take part in the study. Six participants did not complete scores but had verbal feedback and were included for analyses where possible. The participants in each component of the study are summarised in Table 1.

Feedback from formative communication OSCE

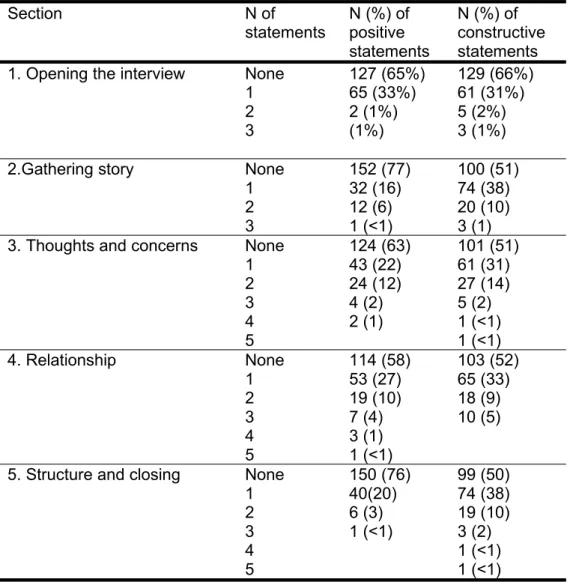

In general, students were given more constructive (median 3 statements,

interquartile range 2-4) than positive feedback (median 2 statements, interquartile range 0-3). Table 2 shows how much feedback the students were given in each area of communication. Numbers of items of feedback differed in each of the 5 sections such that students were given most feedback about structure of the consultation, building and maintaining the relationship, and asking about/responding to thoughts and concerns.

Action planning undertaken

185/196 (94%) of students made one or more action plans. Figure 1 shows how many action plans students made. The modal number of action plans was 3.

Specific action plans

Of the action plans made, N=31 students made specific action plans that matched the feedback given. (16%) – i.e. action plans in the area of communication that matched the feedback that they had been given. 6 students (3%) made specific action plans that didn’t match the feedback given.

i.e. 16% of those who engaged in the formative OSCE wrote specific action plans that were related to the feedback given. These are referred to as responsive specific action plans

Discussion

Students engaged with the process of the formative OSCE feedback and action planning process. The vast majority of students wrote one or more action plans. However, most of these didn’t write specific action plans. In addition, even in the minority that did make specific action plans, some weren’t related to the feedback that they had been given. Students seemed to struggle with making action plans specific and useful, and relate these to their experiences. It might be that students don’t know how to make action plans, don’t see the need for doing so, or that our training of the students in how and why to make action plans was not clear. This study adds to the growing body of literature which demonstrates the need to understand feedback receptivity, not just feedback delivery.

that the language used in the feedback wasn’t direct enough, as found by Ginsburg et al [9].

In conclusion, this study shows that medical students are mostly not making good enough action plans to improve their performance. There are a number of

implications of this work for medical education. Instead of an ongoing focus on increasing the quantity and quality of educators’ feedback, this study suggests that we need to understand how learners make sense of the feedback they receive, accepting or rejecting it, and then incorporating it (or not) into a plan to change. Similarly, for action planning – we shouldn't be focused just on encouraging students to make more action plans; but to understand why they don't make them.

Ethical approval

Ethical permission was granted by x University senate ethics committee.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the students who took part in this study and the tutors who facilitated the teaching sessions.

Declarations of interest.

References

1. Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans.

American Psychologist 1999; 54, 493-503.

2. Juwah C, Macfarlane-Dick D, Matthew B, Nicol D, Ross D, Smith R. Enhancing student learning through effective formative feedback. Higher Education Academy 2004.

3. Hattie J, Timperley H. The power of feedback. Rev Educ Res 2007; 77: 81–112.

4. Maguire P, Goldberg D. The value of feedback in teaching interviewing skills to medical students. Psychol Med 1978; 8:695-704.

5. Ramani S, Krackov K. Twelve tips for giving feedback effectively in the clinical environment. Med Teach 2012; 34: 787–791

6. Harrison CJ, Konings KD, Molyneux A, Schuwirth L, Wass V, van der Vleuten CPM. Web-based feedback after summative assessment: How do students engage? Med Educ 2013; 47: 734–744.

7. Pelgrim EAM, Kramer AWM, Mokkink HGA, van der Vleuten C. Written narrative feedback, reflections and action plans in single-encounter observations: an

observational study Perspect Med Educ 2013; 2(2): 106–108.

8. Harrison C, Hart J, Wass V. Learning to communicate using the

Calgary-Cambridge framework. Clin Teach 2007; 4: 159–164.

9. Ginsburg S, van der Vleuten CPM, Eva KW, Lingard L. Hedging to save face: a

linguistic analysis of written comments on in-training evaluation reports. Advan in

Table 1. N, mean and standard deviation for groups of students for comparisons Formative OSCE

N Mean %

SD

Study sample 1961 81.66 9.99

Any action plan 185 81.89 10.01 No action plan 11 77.84 9.19 Specific action plan 37 82.86 9.97 No specific action plan 158 81.38 10.00 Responsive specific

action plan

31 83.47 10.13

Unresponsive specific action plan

6 78.12 8.43

16 students did not have the written formative OSCE scores although they did take part in the

Table 2: Number of items of positive and constructive feedback statements following formative OSCE station in each area of communication.

Section N of

statements

N (%) of positive statements

N (%) of constructive statements 1. Opening the interview None

1 2 3 127 (65%) 65 (33%) 2 (1%) (1%) 129 (66%) 61 (31%) 5 (2%) 3 (1%)

2.Gathering story None 1 2 3 152 (77) 32 (16) 12 (6) 1 (<1) 100 (51) 74 (38) 20 (10) 3 (1) 3. Thoughts and concerns None

1 2 3 4 5 124 (63) 43 (22) 24 (12) 4 (2) 2 (1) 101 (51) 61 (31) 27 (14) 5 (2) 1 (<1) 1 (<1) 4. Relationship None

1 2 3 4 5 114 (58) 53 (27) 19 (10) 7 (4) 3 (1) 1 (<1) 103 (52) 65 (33) 18 (9) 10 (5)

Figure 1: Percentage of students making each amount of action plans (students made between 0 and 6 action plans)

none one two three four five six

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

6 6

19

52 10

6 1

Percentage of students

N

um

be

r

of

a

ct

io

n

pl

an