Internet Use and Collegiate Academic

Performance Decrements: Early Findings

By Robert W. Kubey, Michael J. Lavin, and John R. Barrows

Recent research at colleges and universities has suggested that some college stu-dents’ academic performance might be impaired by heavier use of the Internet. This study reviews the relevant literature and presents data from a survey of 572 students at a large public university. Heavier recreational Internet use was shown to be correlated highly with impaired academic performance. Loneliness, staying up late, tiredness, and missing class were also intercorrelated with self-reports of Internet-caused impairment. Self-reported Internet dependency and impaired aca-demic performance were both associated with greater use of all Internet applica-tions, but particularly with much greater use of synchronous communication ap-plications such as chat rooms and MUDs, as opposed to asynchronous apap-plications such as email and Usenet newsgroups.

Use of the Internet as a resource for education enjoys near-universal support from students, parents, educators, and institutions, including the United States govern-ment. As former Vice President Albert Gore has said, “We have made progress in reaching our goal of connecting all of the nation’s schools and classrooms to the Internet by the year 2000” (Gore, 1998). One online survey reports that 68% of parents, 69% of students, and 69% of teachers said that they have personally seen students’ grades improve through use of the Internet (AT&T, 1998). However, although use of the Internet by students is on the rise, so are concerns that for some students, heavier use of the Internet might interfere with academic achievement, conventional social interaction, and exposure to desirable cultural experiences. The issue has come up increasingly on scores of college campuses, but no-where more publically than at William Woods University in Fulton, Missouri. In May of 2000 the 1,400-student university announced to the world that it had instituted a new program wherein undergraduate students will earn $5,000 each year against the school’s $13,000 tuition as long as they scored enough points attending various designated cultural events on campus. The program was

de-Robert Kubey is director of the Center for Media Studies and associate professor of journalism and media studies at Rutgers University, Michael Lavin is a professor of psychology at St. Bonaventure University, and John Barrows is director of communication for RCI. The authors wish to thank a number of students who helped with data collection, coding, and input, especially Barna Donovan, Hyo Kim, and Shirin Zarqa.

scribed in numerous news reports as being an antidote to students’ Internet use. (The university’s new “Lead Award” program rewards students with two points, for example, for attending a 2-hour concert. Students must earn at least four points each month and a total of 45 points for the year to receive their $5,000 reward.) Although the university’s official website statement on the program (www.williamwoods.edu) doesn’t emphasize that the program is designed to move students offline, the press reports surrounding the program did, and the university prominently linked its webpage to two stories: a very supportive Bob Greene (May 9, 2000) Chicago Tribune column and a National Public Radio “All Things Considered” program from May 1. Both the Tribune editorial, entitled “The Place to Find Life Is Not a Keyboard,” and an Associated Press story claiming that the university was “concerned that students spend too much time surfing the Internet” quoted the university’s vice president and dean of academic affairs, Lance Kramer, saying, “After all the technically challenging things are mastered, we were con-cerned we weren’t combining them with cultural understandings, human sensi-tivities.” Kramer cited a recent performance of a renowned harpist that attracted a mere dozen people including just three students.

Greene of the Tribune concluded that “someone at William Woods University . . . is paying close attention to what is happening to our society. And that person has a clearer understanding of the troubling aspects of our new computer-cen-tered world than do many analysts who for years now have been saying that the worldwide computer network is the very embodiment of the future.”

Researchers who have studied Internet use by college students claim that a small percentage of students, roughly 5–10%, may suffer harmful effects, such as craving, sleep disturbance, depression, and even withdrawal symptoms in asso-ciation with excessive time online. Scherer (1997) found that 13% percent of col-lege students fit a classification of Internet dependency. Anderson (1999) con-cluded that 9.8% of students surveyed were Internet dependent, most promi-nently, those majoring in the hard sciences.

Studies of general Internet users suggest that some people may experience psychological problems such as social isolation, depression, loneliness, and time mismanagement related to their Internet use (Brenner, 1997; Kraut, Patterson, Lundmark, Kiesler, Mukophadhyay, & Scherlis, 1998; Young, 1996), and Morahan-Martin & Schumacher’s (1997) research has focused on problems of loneliness and heavy Internet use, particularly in college students. Some of these studies (e.g., Kraut et al., 1998; Young, 1996) have been received with a good deal of skepticism, with critics frequently pointing to the self-selection of the samples, or maintaining that there is no such thing as “Internet addiction” (Brown, 1996; Caruso, 1998; Grohol, 1995; Holmes, 1997). To date, very little of the empirical research has been cross-referenced, and common findings have rarely been explored. The terminology employed in the literature has also sparked controversy as the word “addiction” is often used (e.g., Kandell, 1998; Young, 1998; Young & Rodgers, 1998) even when, for well over a decade, contemporary psychiatric and psycho-logical diagnosis in North America has used the term “dependency.”

Regarding scholastic performance, Scherer has concluded that “excessive Internet use is problematic when it results in impaired functioning such as compromised

grades or failure to fulfill responsibilities” (Scherer, 1997, p. 656). Following this and other assertions in the literature, the study reported here is based in the following research questions:

RQ1. Is there self-report evidence to support the concept of Internet depen-dency in college students? If so, what are its correlates?

RQ2. Is there evidence that heavier Internet use and/or so-called Internet de-pendency may be associated with self-reported academic performance prob-lems among college students?

Background Addiction and Internet Dependency

Addiction and dependency have been studied for more than 100 years, yet there remains “no single set of causal factors that enjoy a majority following among researchers and clinicians” (Butcher, 1988, p. 171). The concept of addiction has been very broadly extended into so-called “excessive appetite disorders” such as pathological gambling and other behaviors, including “love, sex, food, dieting, jogging, television—even religion” and video game play (Kubey, 1996; Milkman & Sunderwirth, 1987, p. 126), as well as computers (Shotton, 1989). Research into “gambling dependency,” formally recognized in the American Psychiatric Asso-ciation Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), has established a set of criteria often used by other researchers looking at dependent behavior. Claims of “sex” or “food” addictions, however, have not been based in research as much as has gambling. Instead, some commentators and researchers apply the DSM criteria to the Internet and replace the word “gam-bling” with the word “Internet,” reaching a conclusion of “addiction” instead of “dependency,” which is the operative DSM term, and despite likely behavioral and psychological differences in the activities.

Early support for the concept of “Internet addiction” comes from Young (1996), who posted a form-based survey on a website that allowed for self-selecting anony-mous input from “avid Internet users” that found that 396 of her self-selecting 496 respondents (79.83%) qualified as “Internet dependent.” Young concludes that “pathological use of the Internet can result in significant academic, social and occupational consequences similar to those problems that have been well-docu-mented in other established addictions such as pathological gambling, eating and alcoholism” (Young, 1996, p. 4). Young’s report has attracted substantial media coverage and, not surprisingly, criticism for self-selection sampling bias. The pub-licity has sparked a debate as to whether excess Internet use can actually consti-tute pathological behavior similar to gambling or substance dependence, or whether heavy Internet use is merely a behavioral manifestation of psychological problems that would find another channel were Internet access unavailable (Brown, 1996; Grohol, 1995; Holmes, 1997).

In university settings, anecdotal evidence of problems stemming from exces-sive Internet use have been reported on various campuses. At Alfred University,

50% of students interviewed after dismissal for academic failure listed excessive Internet usage as a reason for their problems (“On Line,” 1996). Morahan-Martin and Schumacher(1997) surveyed 283 college undergraduates in courses that re-quired Internet use. The group in the upper third of use in their study were deemed “pathological users” and averaged 8.5 hours of Internet use per week. The “pathological” group was differentiated from those in the middle and lower third of use (averages of 3.2 and 2.4 hours per week, respectively) as reporting significant loneliness on the UCLA loneliness scale.

Scherer (1997) surveyed 531 university students and found 13% fitting her cri-teria for Internet dependency. Internet-dependent students were predominantly male and reported more leisure-time Internet use than nondependent students. Internet “addiction” among college students also has been identified at National Chiao Tung University in Taiwan (Chou, Chou, & Tyan, 1998).

Brenner (1997) posted a survey on Internet usage on a website, consisting of 32 true-false questions under the title, “Internet-Related Addictive Behavior Inven-tory.” As with Young, Brenner’s survey relates Internet usage to substance abuse. Brenner found that most respondents reported instances of the Internet interfer-ing with time management. A subgroup indicated problems consistent with the classic addiction model such as craving, increasing tolerance, and withdrawal symptoms. Brenner also found that younger users tended to report more prob-lems, and Anderson (1999), studying 1,300 college students from eight different colleges and universities, found that reports of Internet dependency were most common among students majoring in the hard sciences.

Some of the foregoing research relies on the DSM criteria either explicitly or implicitly as the basis for determining dependency. Few, if any, of these studies offer alternative theoretical explanations as to why the Internet might have such a considerable hold on some individuals, either from the substantial literature on substance and behavioral dependency, or from the research on media and televi-sion dependence (Kubey, 1996; McIlwraith, Jacobvitz, Kubey, & Alexander, 1991) or computer-mediated communication dependence (Shotton 1989). The consen-sus across these studies is that Internet dependency is more common among males and, fairly obviously, coincides with heavy use.

Synchronous and Asynchronous Communication Internet Applications

Use of the Internet for communication with family and friends is well established (Katz & Aspden, 1997; Kraut et al., 1998), as is the use of the Internet to make new friends (Horn, 1998; Katz & Aspden, 1997; Rheingold, 1993; Turkle, 1994).

Studies of home Internet use (Kraut et al., 1998) and campus Internet use (Anderson, 1999; Scherer, 1997) show that electronic mail and World Wide Web browsers are the most often-used Internet applications. Use of these applications is significantly greater among those designated “Internet-dependent” and who consistently log more time online than do nondependent users (Anderson, 1999; Scherer, 1997; Young, 1996). Individual applications other than Web browsing and email tend to account for a relatively small percentage of total time spent online and, as such, have been noted but remain relatively underexplored.

vari-ous capabilities and characteristics of different computer communication applica-tions in terms of modality (see Rice, 1984; Walther, 1994, 1996). Synchronous applications such as chat rooms and Multiple User Dungeons (MUDs) permit users to communicate simultaneously, in “real time,” as with telephone conversa-tion, whereas asynchronous applications such as email and Usenet newsgroups are modes in which people communicate in turn, one at a time, as with an ex-change of written letters.

Studies looking at so-called Internet dependency (Anderson, 1999; Scherer, 1997; Young, 1996) have found significantly higher use of synchronous communi-cation Internet applicommuni-cations such as Internet Relay Chat (IRC), MUDs, or variations of each, e.g., Multiple Object-Oriented Domains or website forums, by Internet-dependent people/students compared with nonInternet-dependents. Young (1996) and Scherer (1997) measured the percentage of respondents who had ever utilized the applications, while Anderson (1999) and our own study measured the amount of time spent using the different applications, all comparing Internet-dependent re-spondents with nondependents.

Scherer’s data (1997) indicate that Internet-dependent students were almost three times more likely than nondependents to use synchronous communication Internet applications (24.5% to 8.9%). Young’s data from “avid Internet users” show that 63% utilized synchronous Internet applications compared with 12% of nondependents. Anderson (1999) examined average daily Internet usage, wherein dependent students averaged 29 minutes of daily use of synchronous communica-tion Internet applicacommunica-tions, nearly 10 times as much as the nondependent students, who spent just 3 minutes per day on average doing the same.

Method

A paper-and-pencil survey was administered to 576 students at Rutgers University prior to the start of three classes. The survey consisted of 43 pretested multiple-choice items on Internet usage, study habits, academic performance, and person-ality measures. Students were asked to report anonymously. An email address was provided for students who might wish to communicate with the researchers for follow-up interviews or questions about the project. The survey instructed re-spondents to report recreational Internet usage, specifying: “We are only inter-ested in your spare time or personal use of the Internet and are not concerned with measuring use that is school- or work-related.” This excluded from the analy-sis heavy Internet usage mandated by either employment or class assignments. These distinctions are a subject for future research, but the choice for this study centered on Internet usage over which students ostensibly have complete control. Previous research into Internet dependency has attempted to verify the exist-ence and validity of the concept using a wide variety of measurements. To exam-ine Internet dependency, this study employed a simple five-point Likert scale to assess students’ self-reported agreement or disagreement with the statement, “I think I might have become a little psychologically dependent on the Internet.” The primary measure of whether students had experienced any academic

impair-ment due to the Internet asked them to denote “About how often, if at all, has your schoolwork been hurt because of the time you spend on the Internet?” The research strategically chose the wording above to maximize the possibility that respondents who felt that they might have become dependent would feel com-fortable indicating so on a survey. It is recognized that the wording increases self-reports of dependency over an item that asked students to agree or disagree with the statement, “I am psychologically dependent on the Internet,” but because researchers working on other dependencies and “addictions” have long known how difficult it can be for respondents to report any difficulty at all due to signifi-cant evaluation apprehension and concerns about self-stigmatization, and because the main aim in this early research has been to study the correlative relationships, rather than attempt to establish hard frequencies and prevalence rates, it was concluded that the measure used was more appropriate to the research questions being asked.

In order to test the validity of the measure, we checked whether our respon-dents’ self-reports reflected other behavioral characteristics consistent with depen-dency and heavier use. For some of these analyses, data were grouped to form an “Internet dependent” group (agree and strongly agree combined) and a “nondependent” group (neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree combined). Given the existing literature on Internet dependence and student behavior, we hypoth-esized that our self-reported measure of Internet dependence would be correlated with psychological factors such as guilt, not having control, using the Internet less if the respondent had more friends, and staying up late, as well as academic impairment and missed classes.

Media use questions measured self-reported length of time using the Internet (in months and years), weekly Internet use (hours, in increments of one), and weekly use of specific areas of the Internet including Web browsing, electronic mail, chat, newsgroups or listservs, website or homepage construction, online shopping, and MUDs. For comparative purposes, self-reported weekly use of tele-vision also was measured. Students were asked also about their feelings and atti-tudes toward the Internet, as well as their own sense of what effects, positive or negative, if any, the Internet might have had on their lives. Five-point Likert scales and five-point frequency scales (never, rarely, occasionally, frequently, very fre-quently) were employed. Self-reported sleep and social behaviors were also mea-sured using a five-point frequency scale with variables grouped into the Internet dependent and nondependent groups outlined above.

Recreational Internet use was broken down into seven interactive formats: surf-ing or browssurf-ing the net, email, chat or IRC, postsurf-ing to newsgroups/forums/listservs, time spent constructing websites, shopping online, and participation in MUDs. Respondents indicated hourly use per week along a 16-point scale ranging from zero to 15 or more in increments of one hour.

Sample Demographics

Nearly 100% (574 of 576) of students present submitted completed surveys; two surveys were excluded because of obvious false reporting, yielding a sample of 572. Two thirds of survey respondents were female (381 of 572). Almost half

(46.5%) were 18 or 19 years of age, 71.5% age 20 or younger, with 93% between 18 and 22 years of age. Ages ranged from 18 to 45, with an average age of 20.25,

SD = 3.06. Ninety percent of respondents were in their first 3 years of college. Second-year students ranked highest (N = 205, 35.9%), followed by first-year (N = 164, 28.7%), third-year (N = 143, 25.0), fourth-year (N = 45, 7.9%), and fifth-year (N

= 14, 2.5%). Clearly, the predominance of students in years 1, 2, or 3 indicates that the sample is not perfectly optimally representative of university populations and is an artifact of the large introductory courses from which the data were drawn. Be-cause the numbers of 4th- and 5th-year students are disproportionately small, these years are collapsed in data calculations below to represent the final year in school.

Students participating in the survey were enrolled in three large, introductory journalism, media studies, and communication courses. This also explains the predominance of female students and tracks with the general proportions of stu-dents in these majors. A majority (63%) responded that they either had declared or intended to declare majors in communication or journalism/media studies. The remainder were spread over more than 40 different fields of study, led by psychol-ogy (37 students), English (23), economics (17), political science (16), history (15), business (12), marketing (12), and sociology (10). Seventeen students declared or indicated intent to declare science majors, mostly in pharmacy (9) or computer science (5).

Results Self-Reported Internet Dependency

Just over 9% (9.26%, 53 students) of the sample agreed or agreed strongly that they might have become a little psychologically dependent on the Internet. Within

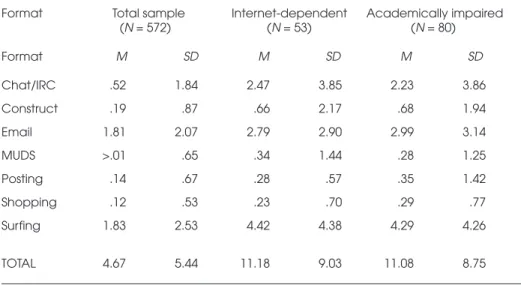

Table 1. Weekly Recreational Internet Usage, in Hours, by Format and Group

Format Total sample Internet-dependent Academically impaired

(N = 572) (N = 53) (N = 80) Format M SD M SD M SD Chat/IRC .52 1.84 2.47 3.85 2.23 3.86 Construct .19 .87 .66 2.17 .68 1.94 Email 1.81 2.07 2.79 2.90 2.99 3.14 MUDS >.01 .65 .34 1.44 .28 1.25 Posting .14 .67 .28 .57 .35 1.42 Shopping .12 .53 .23 .70 .29 .77 Surfing 1.83 2.53 4.42 4.38 4.29 4.26 TOTAL 4.67 5.44 11.18 9.03 11.08 8.75

this subgroup, Internet use was more than double that of the total sample (see Table 1).

The students indicating some dependence (N = 53) were significantly more likely than nondependent students to report agreeing or strongly agreeing, versus being neutral or not agreeing, with the following Likert statements:

1. “Sometimes I think it would be better if I spent less time on the Internet” (χ2 = 9.904,

p < .01).

2. “Some people have suggested to me that I spend too much time on the Internet” (χ2 = 103.555, p < .01).

3. “I feel that I do not always have really good control over my Internet use” (χ2 = 27.634, p < .01).

4. “I think that if I had a few more friends here at school I would probably use the Internet less” (χ2 = 32.554, p < .01).

5. “Sometimes I feel a little guilty about the amount of time I spend on the Internet” (χ2 = 63.095, p < .01).

Internet-dependent students (N = 53) also chose the “frequently” or “very fre-quently” categories, versus being neutral or not agreeing, significantly more often than did nondependent students in response to the following questions:

1. “About how often does the Internet keep you up late?” (χ2 = 80.577, p < .01).

2. “About how often do you feel tired the next day due to late night Internet use?” (χ2 = 59.165, p < .01).

Male participants comprised half (49%) of the self-reported Internet-dependent subgroup, consistent with Scherer’s (1997) findings in which males were 21% more prevalent among dependent than nondependent students. Age was not a significant factor, but year in school showed a slight linear trend from first year through final years, with first-year students (28.7% of sample) disproportionately represented in the Internet-dependent subgroup (37.7% of subgroup).

Internet-dependent students also indicated significantly (χ2 = 11.435, p < .01)

more years of experience using the Internet than nondependent students; 79.2% of dependents had used the Internet for 2 to 3 years or longer compared with 55.1% of nondependent students, and five times as many dependent students (35.9%) had used the Internet 4 years or longer compared with only 7.5% of nondependent students.

Internet-dependent students also spent nearly three times as much recreational time online each week than did nondependent students. Measuring only recre-ational use, excluding both schoolwork and job-related time online, dependent students averaged 11.18 hours of weekly Internet use as opposed to 3.84 hours for nondependent students.

Academic Impairment

In response to the question, “About how often has your schoolwork been hurt because of the time you spend on the Internet,” using a five-point frequency

scale, 80 students (14% of the total sample) reported that their schoolwork had

been hurt occasionally, frequently, or very frequently due to Internet use. Thirty of these students (56.6% of the Internet-dependent group) were among the sub-group of 53 students who reported Internet dependency. Proportionately, then, four times as many of the Internet-dependent students reported Internet-related academic impairment than did the nondependent. Students in the academically impaired subgroup (N = 80) also reported Internet usage more than double that of the sample as a whole (Table 1).

Of the students in the academically impaired subgroup (N = 80), 40% reported that their Internet use had kept them up late at night frequently or very frequently; 42.5% indicated that they sometimes felt tired the next day due to their Internet use; and 20% reported that they had occasionally, frequently, or very frequently missed class because of their Internet use. The same rough linear trend observed for year in school within the Internet-dependent subgroup (N = 53) is seen in the schoolwork-impaired subgroup.

Likert items were employed to compare feelings and opinions about Internet use within the academically impaired group vs. their nonimpaired counterparts with the variable measured according to impairment (occasionally, frequently, and very frequently) versus low or no academic impairment (rarely or never). These responses indicate further support for the claim that there is a relation-ship between Internet dependency and academic impairment, at least in some students:

1. “Sometimes I think it would be better if I spent less time on the Internet.” The academically impaired group was more than twice as likely to agree or agree strongly with this statement than was the nonacademically impaired group (χ2 =

13.287, p < .01).

2. “Some people have suggested to me that I spend too much time on the Internet.” Academically impaired subgroup respondents were more than four times as likely to agree or agree strongly with this statement (χ2 = 61.356, p < .01).

3. “I feel that I do not always have really good control over my Internet use.” Academically impaired subgroup respondents were three times more likely to agree or agree strongly with this statement (χ2 = 23.671, p < .01).

4. “I think that if I had a few more friends here at school I would probably use the Internet less.” Academically impaired subgroup respondents were five times more likely to agree or agree strongly with this statement (χ2 = 26.572, p < .01).

5. “Sometimes I feel a little guilty about the amount of time I spend on the Internet.” Academically impaired subgroup respondents were four times more likely to agree or agree strongly with this statement (χ2 = 85.751, p < .01).

Students in the academically impaired group also used the “frequently” or “very frequently” categories significantly more often than did nonimpaired students in response to the following questions:

1. “About how often does the Internet keep you up late?” Academically im-paired subgroup respondents were 10 times more likely to respond “frequently” or “very frequently” to this question (χ2 =101.597, p < .01).

2. “About how often do you feel tired the next day due to late night Internet use?” Academically impaired subgroup respondents were more than 16 times more likely to respond “frequently” or “very frequently to this question (χ2 = 52.394, p

< .01).

It is not surprising that a high percentage of Internet use, particularly email and chat, involves communication with friends or family. In another Likert item, a significant but slight difference was found between the Internet-dependent and academically impaired groups and the rest of the sample (about 15% for both), indicating that these two groups, for which there is considerable overlap, are using more of their weekly recreational Internet use to stay in touch with friends from high school.

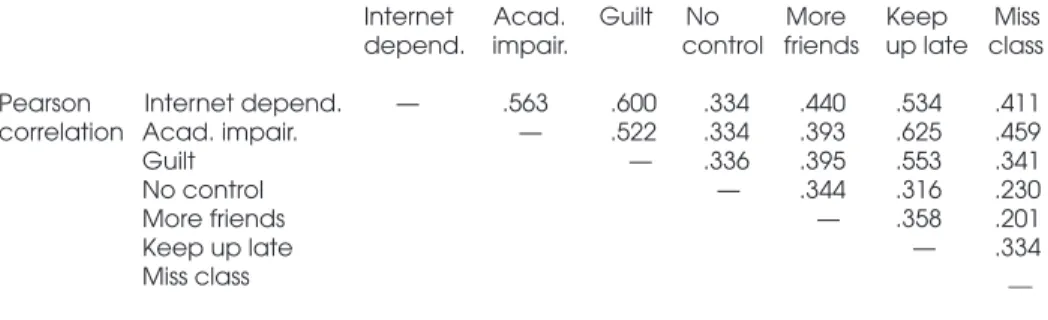

In further examination of internal validity for Likert statement responses (Table 2), relatively high and significant correlations (R = .201 to .625) are seen across various self-reported indicators of Internet dependency and academic impairment, with the percentage of variance accounted for ranging between 15% and 36% in all but two instances. These correlations were also similar across the students’ different fields of study, whether indicated as a declared major or intended major.

Loneliness and Interpersonal Communication

Previous Internet dependency studies have examined dynamics of interpersonal relationships, including use of the Internet to meet new friends, or looking at loneliness as a predictor of dependency. Scherer (1997) found dependent stu-dents 26.2% more likely than nondependent stustu-dents to use the Internet to “meet new people” and 28.8% more likely to “explore new sides of my personality,” including saying things that would not be said face-to-face, or pretending to be someone different. Kraut et al. (1998) also observed that greater Internet use was associated with increased loneliness. Our study found that dependent students felt significantly “more alone than other students” (2 x 2 chi square, χ2 = 27.740,

p < .01). Both studies strongly suggest that loneliness is a factor associated with heavier Internet usage. If Internet dependency and academic impairment stem partly from the heavier Internet use of lonely students communicating with friends

Table 2. Bivariate Correlations of Internet Dependency and Academic Impairment Variables

Internet Acad. Guilt No More Keep Miss depend. impair. control friends up late class Pearson Internet depend. — .563 .600 .334 .440 .534 .411 correlation Acad. impair. — .522 .334 .393 .625 .459

Guilt — .336 .395 .553 .341

No control — .344 .316 .230

More friends — .358 .201

Keep up late — .334

Miss class __

and family, a significantly increased use of specific Internet computer applications for this purpose should be observed in the data, and indeed this is so.

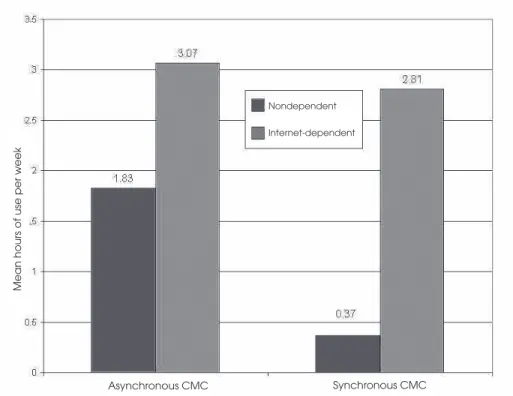

Internet Formats and Usage

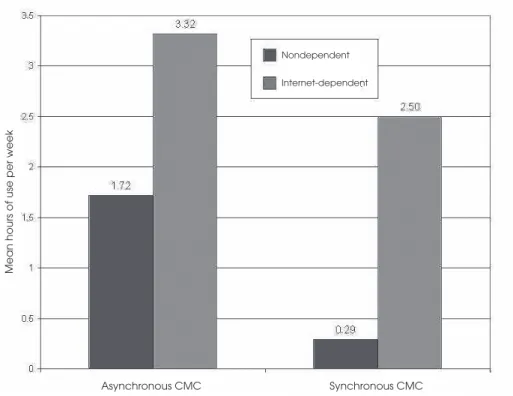

Use of all Internet formats is greater in the Internet-dependent and academically impaired subgroups than in their nondependent and nonimpaired counterparts. The frequency of chat/IRC use is most dramatic, but accounts for less than one third of overall Internet use. Measuring only leisure-time Internet use, we found the self-reported Internet-dependent students averaging just 2.81 hours per week using synchronous (versus asynchronous) communication Internet applications compared with 20 minutes on average for the nondependent students. This very significant difference is accounted for by roughly half (52%) of the 53 self-reported dependent students, with the other half (48%) indicating zero usage. Thus, the actual weekly use of these applications for those who use them is 5.6 hours per week.

This polarized trend, where half the students register zero use of synchronous CMC, appears at least partly due to the limited availability of the applications. Virtually all standard Internet software packages provide electronic mail and Web-browsing software, but software for IRC and MUDs is not always included. For example, computers provided for student use at Rutgers University libraries

in-Figure 1. Internet dependency and computer-mediated communication modality

Asynchronous CMC Synchronous CMC

Nondependent

Internet-dependent

clude Internet browsing software as well as access to email, but not access to IRC chat rooms or MUDs. To date, research has not filtered out this factor in order to differentiate Internet users who are registering zero time with synchronous com-munication Internet applications, despite their availability from those registering zero time because the applications are unavailable.

To further explore the implications of the significantly increased usage of syn-chronous CMC, data were recalculated, combining weekly hours of usage of MUDs and IRC/chat, which had been collected and measured separately, into a new variable representing total use of synchronous CMC. The same data collected separately for email and Usenet/listserv posting were combined into a new vari-able representing asynchronous CMC. Web browsing, posting, and site construc-tion data were not included in this analysis.

Independent t-tests were used to compare the mean usage of synchronous and asynchronous applications by students who self-reported Internet dependency (N

= 53), academic impairment because of excess Internet use (N = 80), and missed classes because of Internet use (N = 22) against the means of their counterparts. Students who self-reported Internet dependency showed somewhat greater use of asynchronous CMC, 1.67 times higher than nondependent students (t =

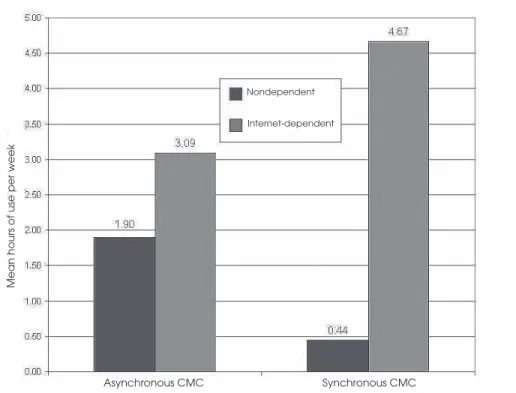

Figure 2. Schoolwork impairment and computer-mediated communication modality (Students reporting that their schoolwork has been hurt occasionally, frequently, or very frequently because of excessive Internet use report significantly increased use of synchronous CMC.)

Synchronous CMC Asynchronous CMC

Nondependent

Internet-dependent

-3.041, p < .001), but reported seven times more synchronous CMC usage than their counterparts (t = -4.244, p < .001; see Figure 1). Students who indicated that their schoolwork had been impaired due to excess Internet use exhibited a similar trend, with nearly twice as much asynchronous CMC use (194%, t = -4.111, p < .001), but use of synchronous CMC is nearly nine times higher (894%, t = -4.818, p

< .001; see Figure 2). Students who reported occasionally or frequently missing class due to Internet use showed a dramatic difference, with synchronous CMC use over 10 times more (1,058%, t = -3.678, p < .001) than students who hadn’t missed class (Figure 3).

Consideration of these findings must be tempered by the fact that the amount of time reported, even when combining applications, is still low with respect to establishing true psychological dependency. Students who report missing class because of Internet use still report, on average, less than 1 hour per day of recre-ational usage of synchronous CMC, which can hardly be considered pathological. At the same time, methodological problems such as more underreporting than overreporting and the general accuracy of self-reported time spent using other electronic media have been documented by researchers looking at television (Kubey,

Figure 3. Missed classes and computer-mediated communication modality (Students who report missing class occasionally, frequently, or very frequently because of excessive Internet usage report significantly increased use of synchronous CMC.)

Asynchronous CMC Synchronous CMC

Nondependent

Internet-dependent

1990; McIlwraith & Schallow, 1983; Singer, 1980). And the relatively low levels of Internet use in this study refer only to recreational use and obviously do not fully capture all use. Overall, the consistency of the findings across different psycho-logical Internet use variables and across different studies strongly indicates that there are significant associated psychological issues.

Discussion

The findings in this study indicate that synchronous applications are quite impor-tant with regard to the common findings of loneliness associated with Internet dependency found in this study and others (Kraut et al., 1998; Scherer, 1997). Synchronous communication offers the opportunity to meet new people and in-teract in ways more similar to face-to-face communication than in asynchronous modes (Walther, 1994).

Synchronous Internet applications can be especially important outlets for lonely people. At any time of day or night, a person can acquire new friends or join up with old cyber-friends in a MUD or chat room. Perhaps no other medium offers such an opportunity for persons experiencing loneliness. Telephone use still gen-erally requires friends or family to call or be called, with norms governing appro-priate times to call and duration of calls, and it is never certain that someone will answer a phone or be available to chat. MUDs and chat rooms, on the other hand, typically operate 24 hours every day, all year long. The increased use of these applications by people reporting problems relating to heavier Internet use is per-fectly logical, and the late night hour component is also important, as this is precisely the time when the rest of the social world is otherwise unavailable. Still, many people spending long hours using synchronous communication Internet applications may well not be lonely at all, or consider themselves to be lonely. Our conventional notions may need to be reexamined.

A significant percentage of students in the academically impaired subgroup in this study reported that their Internet use had kept them up late at night, that they sometimes felt tired the next day, and that they missed class due to Internet use. The new nature of collegiate life for some young persons could result in a devel-opmental retreat, as the Internet does offer a ready and convenient haven that the young college student, often living away from home for the first time and perhaps unable to control little elsewhere, can control when at the keyboard. Contempo-rary first-year college students also often form small listservs of their high school friends to keep in touch and chat late at night, allowing them to keep a group of close friends much more in play than has any previous cohort of college students. This may be another element that contributes to some new students not entering more fully the social rough-and-tumble of their new college environments.

The unique social qualities of synchronous communication Internet applica-tions such as MUDs and chat rooms require further study, as they represent a most significant utility for otherwise lonely individuals who can be with “friends” at any time of day or night, rather than using the telephone or seeking out would-be friends down the hall or across the quad.

Research on television viewing also may provide valuable insight into Internet habits. Studies have identified a variety of theories that explain excessive and “dependent” television viewing (Kubey, 1996; Kubey & Csikszentmihalyi, 1990; McIlwraith et al., 1991; McIlwraith & Schallow, 1983; Singer, 1980).

There is strong evidence that students’ excessive Internet use sometimes is associated with academic problems, but it is not entirely clear whether these students might have experienced similar or related problems without the Internet if the problems result—as the data suggest—from the attempt to control loneliness rather than from properties of the Internet itself. The Internet does enable oppor-tunities for social contact that did not exist before its invention and wide use, and thus we are inclined to conclude that the Internet does play a role in some stu-dents’ academic difficulties. Thus, we think it wise that academic administrators, faculty, staff, and collegiate health workers become increasingly aware of what appears to be a relatively small but growing problem on campus, particularly with undergraduate populations. Whether administrators need to go to the lengths that William Woods University has chosen is open to debate.

We also might consider these findings in light of the report of October 1999 by the American Council on Education and the University of California at Los Angeles Higher Education Research Institute (Sax, Astin, Korn, & Mahoney, 1999). Thirty percent of the 1999 fall entering class, from 462 institutions, and based in 261,217 completed surveys, reported being stressed and overwhelmed. Only 16% reported feeling similarly stressed in the 1985 survey, and the percentage of students re-porting oversleeping and missing class rose from 34.5% in 1998 to 36.2% in 1999. More than two thirds of students reported coming late to class. Whether Internet use is a causative factor or a manifestation of student stress or other factors re-mains to be seen.

References

Anderson, K. (1999, August). Internet use among college students: Should we be concerned? Paper presented at the American Psychological Association, Boston, MA.

American Council on Education & University of California at Los Angeles Higher Education Research Institute. (2000, January). The American freshman: National norms for fall 1999. [Online]. Available: http://www.gseis.ucla.edu/heri/test/executive.htm

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

AT&T. (1998). Internet deserves a top spot on the back-to-school shopping list. [Online]. Available: http://www.att.com/press/0998/980902.csa.html.

Brenner, V. (1997). Psychology of computer use: XLVII. Parameters of Internet use, abuse and addic-tion: The first 90 days of the Internet usage survey. Psychological Reports, 80, 879–882.

Brown, J. (1996). BS detector: “Internet addiction” meme gets media high. Wired, 8(44). [Online]. Available: http://www.wired.com.

Butcher, J. (1988). Introduction to the special series. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(2), 171.

Caruso, D. (1998, September 14). Critics are picking apart a professor’s study that linked Internet use to loneliness and depression. New York Times, C5.

Chou, C., Chou, J., & Tyan, N. (1998, February). An exploratory study of Internet addiction, usage and communication pleasure. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology, St. Louis, MO.

Gore, A. (1998). Connecting all Americans for the 21st century: Telecommunications links in low income and rural communities. Internet Access in Public Schools. [Online]. Available: http://nces.ed.gov. Greene, B. (2000, May 9). The place to find life is not a keyboard. Chicago Tribune, Tempo, p. 1. Grohol, J. (1995). Unprofessional practices on “Internet addiction disorder.” Dr. Grohol’s mental health

page. [Online]. Available: http://psychcentral.com/new2.htm.

Holmes, L. (1997). Internet addiction—is it real? Mining co. guide to mental health resources. [Online]. Available: http://mentalhealth.tqn.com/library/weekly/ aa031097.htm.

Horn, S. (1998). Cyberville: Clicks, culture, and the creation of an online town. New York: Warner Books.

Kandell, J. (1998). Internet addiction on campus—The vulnerability of college students. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 1(1), 46–59.

Katz, J., & Aspden, P. (1997). A nation of strangers? Friendship patterns and community involvement of Internet users. Communications of the ACM, 40, 81–86.

Kraut, R., Patterson, M., Lundmark, V., Kiesler, S., Mukophadhyay,T., & Scherlis, W. (1998). Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? Ameri-can Psychologist, 53(9), 1017–1031.

Kubey, R. (1996). Television dependence, diagnosis, and prevention: With commentary on video games, pornography, and media education. In T. MacBeth (Ed.), Tuning in to young viewers: Social science perspectives on television, 221–260. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Kubey, R., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Television and the quality of life: How viewing shapes every-day experience. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

McIlwraith, R., Jacobvitz, R., Kubey, R., & Alexander, A. (1991). Television addiction: Theories and data behind the ubiquitous metaphor. American Behavioral Scientist, 35, 104–121.

McIlwraith, R., & Schallow, J. (1983). Adult fantasy life and patterns of media use. Journal of Commu-nication, 33(1), 78–91.

Milkman, H., & Sunderwirth, S. (1987). Craving for ecstasy: The consciousness and chemistry of escape.

Lexington, MA: Lexington Books/Heath.

Morahan-Martin, J., & Schumacher, P. (1997). Incidence and correlates of pathological Internet use in college students. Paper presented at the 105th annual meeting of the American Psychological Asso-ciation, Chicago, IL.

On Line. (1996, April 26). Chronicle of Higher Education, 42(33), A21.

Rheingold, H. (1993). The virtual community: Homesteading on the electronic frontier. New York: Addison-Wesley.

Rice, R. (1984). Mediated group communication. In R. Rice & Associates (Eds.), The new media: Communication, research, and technology, 129–156. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Sax, L., Astin, A., Korn, W., & Mahoney, K. (1999, December). The American freshman: National norms for fall 1999. Los Angeles:American Council on Education & University of California at Los Angeles Higher Education Research Institute.

Scherer, K. (1997). College life online: Healthy and unhealthy Internet use. Journal of College Student Development, 38(6), 655–665.

Shotton, M. (1989). Computer addiction? A study of computer dependency. London: Taylor & Francis.

Singer, J. (1980). The power and limitations of television: A cognitive-affective analysis. In P. Tannenbaum (Ed.), The entertainment functions of television, 31–65. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Turkle, S. (1994). Life on the screen: Identity in the age of the Internet. New York: Simon & Schuster. Walther, J. (1994). Interpersonal effects in computer-mediated communication. Communication

Re-search, 21(4), 460–487.

Walther, J. (1996). Computer-mediated communication: Impersonal, interpersonal and hyperpersonal interaction. Communication Research, 23(1), 3–43.

Young, K. (1996). Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. [Online]. Available: http://www.pitt.edu/~ksy/apa.html.

Young, K. (1998). Caught in the net: How to recognize the signs of Internet addiction—and a winning strategy for recovery. New York: Wiley.

Young, K., & Rodgers, R. (1998). The relationship between depression and Internet addiction.