Dennis J. Gallagher

Auditor

Office of the Auditor

Audit Services Division

City and County of Denver

City Vehicle Fleet Management

Performance Audit

The Auditor of the City and County of Denver is independently elected by the citizens of Denver. He is responsible for examining and evaluating the operations of City agencies for the purpose of ensuring the proper and efficient use of City resources and providing other audit services and information to City Council, the Mayor and the public to improve all aspects of Denver’s government. He also chairs the City’s Audit Committee.

The Audit Committee is chaired by the Auditor and consists of seven members. The Audit Committee assists the Auditor in his oversight responsibilities of the integrity of the City’s finances and operations, including the integrity of the City’s financial statements. The Audit Committee is structured in a manner that ensures the independent oversight of City operations, thereby enhancing citizen confidence and avoiding any appearance of a conflict of interest.

Audit Committee

Dennis Gallagher, Chair Robert Bishop

Maurice Goodgaine Robert Haddock

Jeffrey Hart Bonney Lopez

Timothy O’Brien

Audit Staff

Audrey Donovan, Deputy Director, CIA Dawn Hume, Internal Audit Supervisor Emily Gibson, Senior Internal Auditor, M.S. Anna Hansen, Senior Internal Auditor, CICA Wayne Leon Sanford, Senior Internal Auditor, CICA Kevin Vehar, Senior Internal Auditor

You can obtain free copies of this report by contacting us at:

Office of the Auditor

201 West Colfax Avenue, Department 705

Denver CO, 80202

(720) 913-5000

Fax (720) 913-5026

Or download and view an electronic copy by visiting our website at:

To promote open, accountable, efficient and effective government by performing impartial reviews and other audit services that provide objective and useful information to improve decision making by management and the people.

We will monitor and report on recommendations and progress towards their implementation.

City and County of Denver

201 West Colfax Avenue, Department 705 Denver, Colorado 80202 720-913-5000 FAX 720-913-5247 www.denvergov.org/auditor

Dennis J. Gallagher

AuditorJanuary 20, 2011 Honorable Guillermo (Bill) Vidal, Mayor

Office of the Mayor

City and County of Denver Dear Mayor Vidal:

Attached is the Auditor’s Office Audit Services Division’s report of their audit of the City and County of Denver’s Fleet Management program for the period July 01, 2009 through June 30, 2010. The purpose of the audit was to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of the Fleet Management program and determine whether internal controls in place were adequate under the circumstances. This audit included examining Denver Public Works, Denver Police, Denver Sheriff, and Denver Fire Department.

Audit work identified several weaknesses surrounding Denver’s Fleet Management operations that can be improved. These issues include a lack of monitoring and accountability over take-home vehicles, inadequate controls over fuel access, opportunities to improve inventory controls, and significant outstanding internal billing transfers. However, the audit identified a best practice regarding parts inventory control. Public Works has appropriate controls in place to mitigate the risk of inaccurate inventory on hand and asset misappropriation and monitor inventory movement from receipt to disbursement. The findings and recommendations presented in this report have identified areas to improve and strengthen the management of the City’s Fleet.

If you have any questions, please call Kip Memmott, Director of Audit Services, at 720-913-5029. Sincerely,

Dennis J. Gallagher Auditor

DJG/ect

cc: Honorable Members of City Council Members of Audit Committee Jack Finlaw Chief of Staff

Mr. Claude Pumilia, Chief Financial Officer Mr. David Fine, City Attorney

Bill Vidal, Mayor January 20, 2010 Page Two

To promote open, accountable, efficient and effective government by performing impartial reviews and other audit services that provide objective and useful information to improve decision making by management and the people.

We will monitor and report on recommendations and progress towards their implementation.

Mr. L. Michael Henry, Staff Director, Board of Ethics

Ms. Lauri Dannemiller, City Council Executive Staff Director Ms. Beth Machann, Controller

To promote open, accountable, efficient and effective government by performing impartial reviews and other audit services that provide objective and useful information to improve decision making by management and the people.

We will monitor and report on recommendations and progress towards their implementation.

City and County of Denver

201 West Colfax Avenue, Department 705 Denver, Colorado 80202 720-913-5000 FAX 720-913-5247 www.denvergov.org/auditor

Dennis J. Gallagher

AuditorAUDITOR’S REPORT

We have completed an audit of the City and County of Denver’s Fleet Management program for the period July 01, 2009 through June 30, 2010. The purpose of the audit was to examine and assess whether Public Works maintains proper internal controls over fuel distribution, review and assess fleet management controls for regularly scheduled vehicle service, determine whether vehicle preventative maintenance controls and practices are adequate, document whether City fiscal rules for vehicle use are being fully complied with, and to evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of fleet management controls for the City departments examined to identify possible inefficiencies and opportunities for improvement.

This performance audit is authorized pursuant to the City and County of Denver Charter, Article V, Part 2, Section 1, General Powers and Duties of Auditor, and was conducted in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Even though the City operates in a decentralized environment regarding fleet management, the goals of each department are similar. The objective of effective and efficient fleet management is to operate by providing the highest quality service at the lowest cost while ensuring the safety and reliability of each vehicle. The audit revealed several weaknesses surrounding Denver’s Fleet Management practices that can be strengthened. These control weaknesses hinder the City’s ability to effectively and efficiently operate the City’s Fleet.

We extend our appreciation to the Department of Public Works, Denver Police Department, Denver Sheriff Department, Denver Fire Department and City personnel who assisted and cooperated with us during the audit.

Audit Services Division

Kip Memmott, MA, CGAP, CICA Director of Audit Services

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1

Finding 1: Lack of Accountability and Monitoring Over Take-Home Vehicles 1

Finding 2: Fuel Access Internal Controls are Inadequate

2

Finding 3: Opportunities Exist to Improve Parts Inventory Controls

2

Finding 4: Significant Outstanding Internal Billing Transfers

3

INTRODUCTION & BACKGROUND

4

SCOPE

11

OBJECTIVE

11

METHODOLOGY

11

FINDING 1

12

Lack of Accountability and Monitoring Over Take-Home Vehicles

12

RECOMMENDATION

17

FINDING 2

19

Fuel Access Internal Controls are Inadequate

19

RECOMMENDATIONS

21

FINDING 3

22

Opportunities Exist to Improve Parts Inventory Controls

22

RECOMMENDATIONS

24

FINDING 4

25

Significant Outstanding Internal Billing Transfers

25

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(cont’d)

APPENDICES

27

Appendix A

–

Fiscal Accountability Rule 10.6

27

Appendix B

–

Results of Take-Home Vehicle Testing

33

Appendix C

–

Internal Billing Process Flow Chart

34

Appendix D

–

Fiscal Accountability Rule 7.7

35

P a g e 1 OOffffiicceeoofftthheeAAuuddiittoorr

Take-home vehicle usage is not always reimbursed by

employees

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The City and County of Denver maintains a fleet of more than 4,000 vehicles and equipment, which are essential for providing city services and conducting city business.1

The management of the City’s fleet is decentralized and managed by three separate Departments; Public Works, Department of Safety, and Department of Aviation. Primary fleet management responsibilities include vehicle purchase, vehicle utilization, vehicle maintenance, and vehicle disposal. The fleet is crucial for service provision and city operations, and as such, it is important for the fleet to be managed efficiently and effectively. The audit identifies several opportunities for enhancing certain fleet management practices.

Finding 1: Lack of Accountability and Monitoring Over Take-Home

Vehicles

There are approximately 475 City employees authorized to take a City vehicle home for the purposes of responding to City emergencies occurring outside of normal business hours. The ability to commute in a City vehicle to and from work is considered an additional form of compensation to the employee that must be valued and accounted for in most cases. Audit work determined that the requirements surrounding take-home vehicles are not being complied with, monitored for enforcement, or being applied consistently.

Problems identified included:

Internal Revenue Service (I.R.S.) required employee reimbursements to the City for commuting in a take-home vehicle do not always occur. In addition, I.R.S. and City regulation exemptions for public safety vehicles are not applied consistently to all departments under the Department of Safety.2 As a result, not all

reimbursement funds are being recovered, which could fund other city activities. Additionally, inconsistent enforcement of this requirement raises equity issues between employees who comply and those

that do not comply with this requirement. This could also result in negative public relations issues for the City.

Audit work identified 11 instances when City take-home vehicle requirements were not followed. Specifically, audit work found four instances where Executive Order requirements and seven instances where Fiscal Rule requirements were violated.3

There is minimal oversight of take-home vehicles beyond the agency level.

1

Equipment includes items such as trailers, lawnmowers, and smaller motorized and non-motorized equipment. 2

The Department of Safety consists of the Denver Police Department, the Denver Sheriff Department and the Denver Fire Department.

3

P a g e 2

C

CiittyyaannddCCoouunnttyyooffDDeennvveerr

Lack of controls over parts inventory creates significant risk

of asset misappropriation

Finding 2: Fuel Access Internal Controls are Inadequate

The Division of Fleet Maintenance under Public Works has the responsibility of managing fuel usage for City vehicles, except for Denver International Airport vehicles. Audit work found that a lack of internal controls over the process to obtain and terminate access to fuel significantly increases the risk that fraudulent fueling could occur. More specifically audit work determined the following:

30 of 81 (37%) active fuel users tested within the City’s fuel management system were no longer employed with the City.

Approximately 1,603 gallons of fuel have been obtained using ID numbers of terminated City employees. Audit work could not determine whether or not the fuel was obtained fraudulently.

Duplicate fueling IDs were issued to the same person on several occasions, increasing the risk of inappropriate use of fuel.

Finding 3: Opportunities Exist to Improve Parts Inventory Controls

The Fleet parts inventory, valued at more than $2 million,4 is considered a City asset and

must be managed and accounted for properly throughout the life of parts from receipt of the inventory to disbursement for repairs. Audit work determined that a lack of internal controls over the parts inventory process at the Denver Police Department (DPD)5 and Denver Fire Department (DFD) leads to inaccurate on hands

and inventory valuation, part out-of-stocks and overstock, increased levels of obsolete and slow moving inventory, and creates significant risk of asset misappropriation.

Audit work identified the following inventory issues:

40% of DPD on hand part counts in the system were incorrect. 50% of DFD on hand part counts in the system were incorrect.

DFD’s parts room is operated by a single parts room manager and due to activities and days off, the part room is occasionally unattended.

Conversely, audit work revealed a best practice with regards to parts inventory control performed at Public Works. Public Works has appropriate controls in place to mitigate the risk of inaccurate inventory on hands and asset misappropriation and monitor inventory from receipt to disbursement. Specifically, the Department has designed reports that fully utilize the inventory management system, FASTER, to monitor inventory movement and keep costs to a minimum without compromising customer service.

4

Public Works 2009 Parts Inventory Report valued inventory at $1,567,297.32. DPD and DFD inventory value of $322,894.18 and $160,543.67 respectively was calculated from inventory listed in Task Force/FASTER in August 2010. Inventory values are unaudited.

5

P a g e 3 OOffffiicceeoofftthheeAAuuddiittoorr

Uncollected revenue directly affects Public Works’ ability to operate and effectively budget

for future activities

Finding 4: Significant Outstanding Internal Billing Transfers

Public Works’ Fleet Maintenance Division uses Internal Billing Transfers (IBTs) as the method for collecting revenues from various city agencies for fleet services provided. Audit work identified a total of 116 or $134,127 outstanding IBTs from 2009 and 2010 that have not been collected by Public Works from various agencies.

Per Fiscal Rule 7.7, the Department is required to track funds billed and ensure they are collected. However, Public Works does not have a process in place to follow up with agencies when an IBT is not received. Since the Department operates in arrears the failure to collect this revenue directly affects their ability to effectively budget and forecast future activities.

P a g e 4 C CiittyyaannddCCoouunnttyyooffDDeennvveerr

INTRODUCTION

& BACKGROUND

Fleet Management

The City and County of Denver maintains a fleet of more than 4,000 vehicles, which include a variety of vehicles and equipment, many of which provide specialized services to citizens and conduct City business.6 Fleet management responsibilities are

decentralized in the City, divided between three departments, the Department of Public Works (PW), the Department of Safety (Safety) and the Department of Aviation, with PW having the broadest fleet management responsibilities.7 Fleet Management for the City’s

vehicles and equipment encompasses much more than preventative maintenance and repairs. Other management responsibilities include:

Managing and billing agencies for the use of the City’s shared motor pool vehicles. These vehicles are available for short-term rental by any City employee for the purpose of conducting city business;

Monitoring and tracking fleet utilization;

Management and maintenance of fleet databases;

Purchasing and distributing various types of fuel, supplies and parts; and Procuring and disposing vehicles and equipment.

City Fleet Management Governance

There are a variety of City, State and Federal rules and regulations that govern the use of the City’s fleet. These include multiple Executive Orders, Fiscal Rules, State Statutes and Internal Revenue Service (I.R.S.) Code regulations that apply to fleet functions such as purchasing, parking, registration, and vehicle disposition. There are three components of regulations that were particularly relevant to this audit, including the I.R.S. Code of Federal Regulations, Fiscal Rule 10.6 and Executive Order 25.

I.R.S. Code of Federal Regulations – I.R.S. Code of Federal Regulations, United States Department of Treasury, Title 26, Ch. 1(A), Part 1, §1.61-21 contains all regulations pertaining to the valuation of taxable fringe benefits. The use of any city vehicle for personal purposes, including commuting to and from work, is considered a fringe benefit under this section of I.R.S. Code. Thus, any City employee authorized to commute in a city vehicle must account for this vehicle usage and it must be valued as a form of compensation to the employee. The City mostly utilizes the I.R.S. approved “commuting

6

The City and County of Denver fleet includes approximately 1,900 units managed by Public Works and approximately 1,300 managed by the Department of Safety and 872 units managed by the Department of Aviation. Information gathered from the 2010 Budget Book, Public Works’ fleet management database, and the city website

http://www.denvergov.org/RentaCityVehicle/tabid/433539/Default.aspx. 7

P a g e 5 OOffffiicceeoofftthheeAAuuddiittoorr

valuation rule” to value this benefit, which requires the employee to reimburse the City $1.50 per commuting trip, or $3.00 per day.

Fiscal Rule 10.68 – This fiscal rule reinforces the I.R.S. requirements for valuing commuting

benefits, which are referred to as “take-home vehicles.” The rule provides additional guidance on tracking commuting usage and reimbursement exemptions, which are mostly for public safety vehicles. The rule also outlines the City’s qualification requirements for take-home vehicles.9

Executive Order 25 – This Order essentially mirrors Fiscal Rule 10.6 and has many of the same guidelines. The Order also requires authorized drivers of “take-home vehicles” to respond to at least 12 emergencies within a 12-month period.

Department of Public Works

’

Fleet Maintenance Division

The Department of Public Works’ Fleet Maintenance Division (PW Fleet), housed under the Department’s Division of Finance and Administration, oversees the main responsibilities for management of the City’s fleet except for those vehicles utilized by Safety and the Department of Aviation. Excluding those departments, PW Fleet is responsible for the maintenance, repair, specification, and retirement of more than 1,90010 City vehicles and pieces of equipment. PW Fleet consists of four

sections that work to accomplish fleet management responsibilities including, administration, maintenance operations, materials handling, and equipment replacement.

In 2009, the 100 Best Fleets Program11 recognized the Department of PWs’ Fleet

Maintenance Division for excellence in operations and fleet management as the second best public sector fleet in North America. The award recognizes and rewards peak performing public sector fleet operations. In addition, the

American Public Works Association named the Fleet Director Professional Manager of the Year.

The PW Fleet Division has also embraced the Mayor’s Greenprint Denver Initiative through purchasing vehicles that utilize alternative fuels and sustainable technologies.12 In fact, the Division’s Fleet has

received awards for being one of the top ten “green” fleets in North America.13

8

See Appendix A for a complete copy of Fiscal Rule 10.6. 9

The requirements are that employee’s job duties must include responding to emergencies or non-scheduled service requests which necessitate the use of specialized equipment and the city vehicle, a signed authorization form submitted to the Controller’s Office, a valid Colorado driver’s license, the driver must reimburse the City for commuting, and the driver’s home cannot be outside a 25 mile radius of the City and County Building.

10

2010 Budget Book pg.462. 11

The 100 Best Fleets Organization recognizes excellence in government fleet management in overall best fleet and green fleet categories based on a variety of criteria.

12

The Greenprint Denver Initiative was announced in 2006 by Mayor John Hickenlooper in an effort to increase energy efficiency and reduce emissions produced by City activities.

P a g e 6

C

CiittyyaannddCCoouunnttyyooffDDeennvveerr

Financial Structure

The daily operations of PW Fleet are accounted for using a proprietary fund structure instead of a governmental fund structure. There are two types of propriety funds, internal service funds, which PW operates as, and enterprise funds. An internal service fund accounts for operations similar to those accounted for in enterprise funds, but provide goods and services to other departments within the same government. In 2010, PW Fleet expects to record approximately $21 million in revenue and $20 million in expenditures, which is a decrease from 2008 levels, but an increase from 2007 levels.14

Maintenance Operations

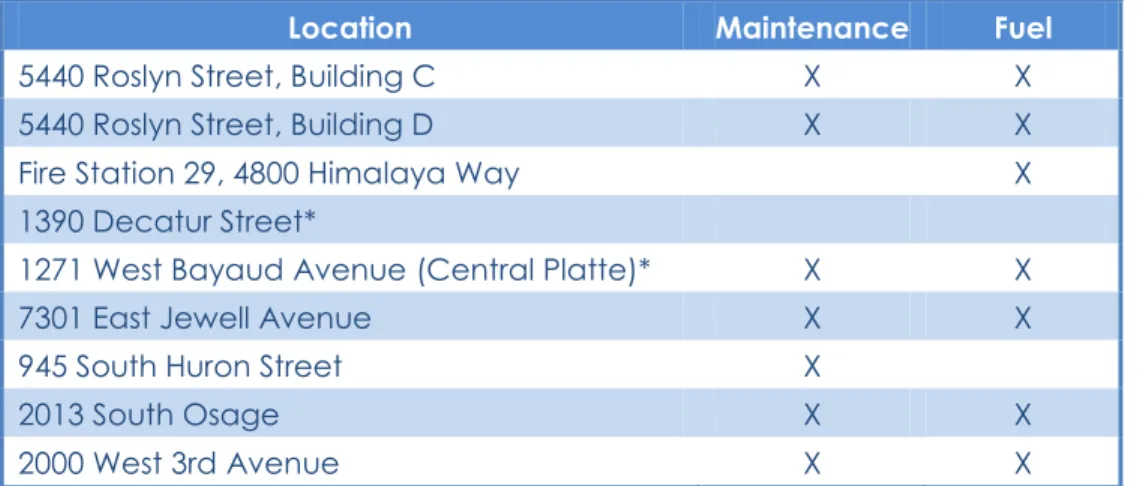

Currently, PW Fleet utilizes seven maintenance and seven fueling locations across the City of Denver for fleet operations. Multiple locations provide an increased level of operating efficiency and customer service. A listing of each location is shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1-PWs Maintenance Facilities and Fuel Stations

Location Maintenance Fuel

5440 Roslyn Street, Building C X X

5440 Roslyn Street, Building D X X

Fire Station 29, 4800 Himalaya Way X

1390 Decatur Street*

1271 West Bayaud Avenue (Central Platte)* X X

7301 East Jewell Avenue X X

945 South Huron Street X

2013 South Osage X X

2000 West 3rd Avenue X X

*Decatur closed 10/1/10 and W. Bayaud opened 10/4/10 In October, PW Fleet opened a new

state-of-the-art maintenance facility that replaced the facility at the Decatur location. The new facility, commonly referred to as Central Platte, was designed with “green” and energy efficient concepts in order to reduce the carbon footprint and the cost of the operations. This new facility features 39,300 square feet of service space, seven heavy equipment bays, nine lube stations and built-in parallelogram lifts to accommodate large trucks. Pictured is the

new Central Platte Facility, located on West Bayaud Avenue, prior to opening.

13

The 100 Best Fleets Organization recognizes excellence in government fleet management in overall best fleet and green fleet categories based on a variety of criteria.

14

2009 and 2010 Budget Book. Audit work identified a lag in collecting revenue from agencies that affects the timing of revenue collected as noted in Finding 4.

P a g e 7 OOffffiicceeoofftthheeAAuuddiittoorr

The Roslyn and Central Platte facilities are the main maintenance locations that also function as central warehouses stocking commonly used parts in addition to handling special orders for satellite maintenance locations. The satellite locations complete lighter maintenance such as tire and oil changes and maintain parts inventory to complete those work orders. Inventory is maintained and controlled in the same manner at all locations.

PW Fleet is also responsible for negotiating the purchase prices, making purchases and distributing fuel used by the City’s fleet, except for Denver International Airport vehicles. In 2009, PW Fleet purchased almost 3 million gallons of fuel costing $5.7 million dollars.15 In addition, some quasi-governmental

agencies16 have access to the fuel purchased by Fleet, which is regulated by

intergovernmental agreements. Fleet will invoice agencies and other authorized users for gallons fueled each month.

Department of Safety Fleet Maintenance Division

Safety manages its own fleet of approximately 1,300 vehicles and equipment. Within Safety, fleet management responsibilities are divided between the Denver Police Department (DPD) and Denver Fire Department (DFD). Both Departments’ fleet activities are funded by the general fund and do not operate through proprietary internal service funds in contrast to the PW Fleet.

Denver Police Department

DPD is responsible for the management and maintenance of approximately 1,100 vehicles and related equipment through their

Research, Training and Technology Division. DPD provides safety services to the citizens of the City and County of Denver through six decentralized districts, encompassing approximately 155 square miles, which means their vehicles are heavily utilized. In 2010, the budget for fleet maintenance was approximately $6 million, a decrease of approximately $600,000 from 2009 levels.17 In addition, DPD has recently downsized

their fleet as a result of the recent economic environment.

DPD has two facilities for fleet maintenance activities, the garage where major repairs and body work is completed and a service center where preventative maintenance

15

Types of fuel purchased consist of diesel, B100 (bio-diesel), unleaded, unleaded 91, E85, and Propane. 16

Quasi-governmental agencies include but are not limited to Denver Health and Denver Housing Authority. 17

P a g e 8

C

CiittyyaannddCCoouunnttyyooffDDeennvveerr

activities and minor repairs is completed. The garage is staffed with 18 mechanics, two parts room employees and the service center that operates with two shifts comprised of eight service technicians.

In addition, DPD fleet maintenance orders, maintains, repairs and equips marked, unmarked, and special use vehicles for the Sheriff’s Department, Office of the District Attorney, Mayors’ Office, County Courts, and four task forces. This adds to DPD’s responsibility approximately 90 cars, vans, and bus units for the Sheriff’s Department.

Denver Fire Department

DFD maintains a fleet maintenance facility in one central location. In 2010, the budget for DFD fleet maintenance was approximately $3.2 million, down approximately $1.3 million from 2009 levels.18

Fleet maintenance responsibilities are comprised of maintaining specialized fire apparatus, approximately 200 vehicles and a parts inventory. In order to properly maintain their fleet and keep costs to a minimum, DFD mechanics have a fully functional machine shop used to make and repair parts and apparatus needed to properly maintain the fleet. All 16 mechanics must be ready to respond if needed to the scene of accidents, fires and any other emergency if immediate repairs are necessary. Both vehicles and specialized apparatus must be maintained to meet standards required by the National Fire Protection Association. Aerial ladders, breathing apparatus, ground ladders and fire hoses are some examples of equipment maintained.

Consolidated Activities

Even though the City has a decentralized model for fleet management, there are some activities outside of maintenance that are consolidated between the PW and Safety Fleets. These activities include, use of fleet management systems, fuel activities, a vehicle replacement fund and the City’s annual vehicle auction.

Fleet Management Systems

The City utilizes two information systems for daily fleet management activities that are shared between PW Fleet and Safety, FASTER and FuelForce. PW utilizes FASTER, implemented in September 2010, for tracking all vehicle maintenance and repair activities for both PW Fleet and Safety.

PW Fleet expects that the new FASTER system will improve the efficiency and effectiveness of operations such as technician performance analysis, warranty management, and parts control. For example, FASTER will provide more effective

18

P a g e 9 OOffffiicceeoofftthheeAAuuddiittoorr

tracking of warranties on vehicles, parts, and equipment, which PW Fleet estimates will save $671,561 over the first five years.19

PW Fleet manages and maintains FuelForce, the City’s software system that tracks, monitors, and administers fuel usage for all city vehicles including several quasi-governmental agencies such as, Denver Health and the Denver Housing Authority through special inter-governmental agreements. PW bills agencies monthly for fuel usage.

In order to access fuel, the employee must enter unique identifying information issued to them by PW Fleet. FuelForce will automatically recognize if any of the entered information does not agree with the information stored in the database and deny access for fuel.

Planned Fleet Replacement and Retirement

New vehicle and equipment purchases for all City departments and agencies are funded through the Planned Fleet Replacement Special Revenue Fund, except for those operating with enterprise funds (i.e. Denver International Airport). Revenues for this fund come from General Fund transfers and interest income. Each department and agency prepare a list of prioritized fleet replacements, which are then submitted to the Budget and Management Office for a final decision on which replacements will be purchased during the budget cycle. In addition, the City has an informal Utilization Committee that meets periodically to review and identify utilized vehicles. Agencies with under-utilized vehicles are given the opportunity to justify retaining the vehicle. The Utilization Committee is comprised of the Director of the Budget and Management Office, Director of PWs Fleet, a representative from the Mayor’s Office, and the Department of Finance. As a method of budget savings in 2010, a majority of scheduled fleet replacements were deferred, saving the City approximately S10.4 million.

PW Fleet annually conducts an auction of used fleet vehicles and equipment. Auctioned items include cars, trucks, vans, heavy machinery, equipment and obsolete parts from all departments and agencies in the City. The auction serves as the main avenue for retiring vehicles once utilization criteria have been met. The auction is conducted by a professional third party auctioneer and is open to the public, including City employees. In 2010, the annual auction sold 169 units generating $977,285.20

Barriers to Further Consolidation

Further consolidation of fleet management responsibilities between PW and Safety is an issue that is periodically discussed by City officials. In the past, PW and Safety representatives have never been able to move beyond the initial discussions. For example, approximately one year ago there were efforts to consolidate parts and inventory management, but that initiative did not progress as the departments involved differ upon terms and administrative functions and responsibilities. Some of the obstacles that would need to be overcome in order to consolidate the operations include:

19

Fleet Management/Maintenance Software Upgrade Proposal, October 21, 2008. 20

P a g e 10

C

CiittyyaannddCCoouunnttyyooffDDeennvveerr

PW operates using an Internal Service Fund, and Safety operates under the General Fund;

Specialty equipment requirements related to DPD and DFD operations;

The DFD collective bargaining agreement that includes mechanics as classified service for rank and grade;

Concerns about priority of repairs and criteria and responsibilities for setting the priority; and

The need for additional support from the Mayor’s Office, PW and Safety in the form of a strategic plan to move forward with possible consolidation.

Benchmarking Suggests that Consolidation is Common

Audit work determined that consolidation of fleet management among other cities is common. In our benchmarking survey, the majority of city fleets indicated that police vehicles were part of the consolidated fleet program. It is less common for fire vehicle fleet consolidation due to the specialized nature of fire vehicles, equipment and maintenance standards. Nevertheless, at least 50% of survey respondents indicated that fire vehicles were part of the consolidated fleet program.21 The Auditor’s Office will

address the feasibility of consolidating fleet operations separately in a Special Advisory Report (SAR) that is scheduled to be released during the first quarter of 2011.

21

We benchmarked the following municipalities—Washoe County, NV, Thornton, CO, Fairfax County, VA, Peoria County, IL, Long Beach, CA, Aurora, CO, Oklahoma City, OK, Austin, TX, and Des Moines, IA. Responses were also solicited from Denver PW. Benchmark criteria is from the International City/County Management Association’s (ICMA) Comparative Performance

Measurement Report on fleet performance based on demographic/organizational data on different fleet management jurisdictions. Additional criteria consisted of types of vehicles, weather, and services provided.

P a g e 11 OOffffiicceeoofftthheeAAuuddiittoorr

SCOPE

The audit assessed the effectiveness and efficiency of the City and County of Denver Fleet Management program for the period July 01, 2009 through June 30, 2010. City entities included with the scope included Denver PWs, Denver Police, Denver Sheriff, and Denver Fire Departments.

Denver International Airport (DIA) was excluded from the audit scope because it operates as a separate City and County of Denver enterprise fund and is highly regulated by the Federal Aviation Administration. DIA Fleet Management operations will be examined in a subsequent Audit Services audit engagement.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this audit was to evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of fleet management operations, and to review and assess internal controls over maintenance practices and fuel distribution.

METHODOLOGY

We utilized several methodologies to achieve the audit objective. These evidence gathering techniques included, but were not limited to:

Interviewing key Public Works, Department of Safety, Controller’s Office and Budget and Management Office personnel;

Reviewing State and Federal regulations regarding fleet utilization reporting; Reviewing City Fiscal Rules and Executive Orders for compliance requirements; Reviewing department policies and procedures for fleet maintenance, fuel distribution, internal billing and fleet vehicle acquisition and disposition;

Reviewing prior internal and external audits regarding fleet management; Reviewing data regarding controls for take-home vehicles, fuel usage and vehicle utilization;

Observing auction process;

Touring fleet maintenance facilities for Public Works and the Department of Safety;

Observing inventory processes and procedures regarding parts management for Public Works, Denver Police Department22 and Denver Fire Department; and

Surveying other cities regarding fleet management practices and measurements.

22

P a g e 12

C

CiittyyaannddCCoouunnttyyooffDDeennvveerr

FINDING 1

Lack of Accountability and Monitoring Over Take-Home Vehicles

As of June 30, 2010, City agencies reported that there are 475 employees authorized to take vehicles home, with DPD, DFD and PW being the largest take-home vehicle entities.23 Take-home vehicles play an important role in the City’s operations to ensure

that critical services to citizens are available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, everyday of the year. Certain employees are granted the use of a take-home vehicle to ensure that emergencies are responded to regardless of the day and time of the emergency. Some examples of emergencies that might require City employee assistance outside of business hours include snow removal, street flooding, power outages, unsafe street conditions and various public safety emergencies.

Employees authorized to take a vehicle home generally use the vehicle, a city asset, for personal use commuting to and from work.24 With a few exceptions, the personal use of

the city vehicle is considered an additional form of compensation to the employee, in other words, a fringe benefit. As such, specific responsibilities and requirements exist to ensure that this personal use is accounted for properly and that take-home authorizations are limited only to those employees who truly need the vehicle to perform their job responsibilities. The intent of Internal Revenue Service (I.R.S.) Code, Fiscal Rule 10.6 and Executive Order 25 is to ensure that take-home use is properly documented, accounted for and transparent.

Audit work determined that requirements surrounding take-home vehicles are not being monitored, complied with, or applied consistently. The numerous problems identified by audit work regarding take-home vehicles ultimately create the perception that the City does not view managing take-home vehicle usage as a high priority.

Non-Compliance with I.R.S. Code of Federal Regulations

I.R.S. Code provides regulations pertaining to employers on how to value fringe benefits, including the use of a company vehicle for commuting.25 It requires that all employees

taking a vehicle home, unless they are exempt as a “Qualified Non-Personal Use Vehicle,” reimburse the City for the personal commuting use of the vehicle.26 Audit work

found that these required reimbursements do not always occur and in other cases do not occur within the pay period for which the car was used.27 The Controller’s Office

23

This information was obtained from the last report prepared by the agencies and submitted to the Budget and Management Office. The exact number of authorized take-home users is unknown, as audit work determined there are several inaccuracies contained in this report.

24

Personal use of a take-home vehicle is limited to commuting to and from work. 25

I.R.S., Code of Federal Regulations, United States Department of Treasury, Title 26, Ch. 1(A), Part 1, §1.61-21. 26

Qualified non-personal use vehicles generally include vehicles such as clearly marked police and fire vehicles and unmarked vehicles used by law enforcement officers if the use is officially authorized.

27

The City utilizes the I.R.S. defined “Commuting Valuation Rule”, which requires reimbursements of $1.50 per one-way trip or $3.00 a day for most employees.

P a g e 13 OOffffiicceeoofftthheeAAuuddiittoorr

reported that if the employee does not submit a trip log,28 the deduction will not be

processed. Additionally, there is no follow up process for collecting trip logs that are not submitted.

The funds recovered for commuting reimbursement are a source of revenue to the City and therefore, if all employees taking vehicles home are not reimbursing properly, the City is not recovering funds it should otherwise be collecting. Further, there could be potential penalties assessed by the I.R.S. for unreported income for both the City and employee receiving the benefit. Additionally, inconsistent enforcement of this requirement raises equity issues between employees who comply and those that do not comply with this requirement. This could also result in negative public relations issues for the City.

Consistent Violations of Fiscal Rule 10.6 & Executive Order 25

Auditors found multiple instances where Fiscal Rule 10.6 and Executive Order 25 take-home vehicle requirements were not being followed. Overall, there was a lack of documentation regarding take-home vehicle usage; as a result it was difficult to determine if some of the employees reviewed truly qualified for a take-home vehicle. Table 2 below displays the number of violations audit work found with respect to each requirement.

Table 2 – Summary of Violations29

Requirement

Number of Violations

in a Sample of 17

Executive Order 25 4

Fiscal Rule 10.6 7

Types of violations that audit work found include:

Half of the employees sampled did not have current, fully executed authorization forms. Four of the authorizations obtained were signed after the audit request was made;

The Controller’s Office did not have authorization forms on file for any employees in our sample and reported they do not receive these for any employee; and The number of emergency responses the employee is making with the take-home vehicle is often not tracked, making it impossible to determine if they have met the requirements for a take-home vehicle.30

28

Trip logs are required by Fiscal Rule 10.6 to be submitted at the end of each pay period to the Controller’s Office. The log tracks commuting mileage and number of commuting trips, along with emergencies responded to in the City vehicle. 29

Some violations in this table are for the same requirement that is part of both the Fiscal Rule and Executive Order. Reference to all audit work results regarding take-home testing can be reviewed in Appendix B. To perform the testing, a judgmental sample of 17 take-home vehicles was selected. Vehicles tested in the sample included eight from Denver Police Department, two from Denver Sheriff Department, five from the Department Public Works and two from the Department of Parks & Recreation. The number of vehicles chosen from each agency was based on the total number of take-home vehicles for that agency.

P a g e 14

C

CiittyyaannddCCoouunnttyyooffDDeennvveerr

Personnel assigned take-home vehicles are required to submit this documentation. These violations illustrate that the City does not have a good command over take-home vehicles, creating the perception that monitoring take-home vehicles is a low priority for the City.

Issues with the Department of Safety’s Management of Take-Home Vehicles

The Department of Safety, mainly the Denver Police Department and Denver Fire Department, are some of the largest users of take-home vehicles, which is appropriate given the nature of their work. Many emergencies responded to by these Departments require immediate response, along with the use of the specialized equipment located on or in the vehicle. As such, when there is an after hours emergency, there is not time for these employees to pick up the vehicle and special equipment prior to responding. Some examples of emergencies Safety personnel respond to with their take-home vehicles include: traffic fatalities, hostage situations, homicide investigations, gang crimes, bomb squad incidents, arson incidents, and hazardous materials incidents.

As noted, I.R.S. Code requires employees to reimburse the City for personal use of an employer provided vehicle as an additional form of compensation to employees. There are two exemptions to this requirement for public safety vehicles. The first exemption, “Qualified Non-Personal Use Vehicle,” is established by the I.R.S. Code. This exemption generally includes vehicles such as clearly marked police and fire vehicles. Owing to the design of these vehicles, it is unlikely that employees will use the vehicle more than minimally for personal use and therefore they are exempt from reimbursement requirements.31 The City established a second exemption for a “Full Use Public Safety

Vehicle.” This exemption can only be granted by the Manager of Safety and exempts the user from both reimbursement and emergency tracking requirements. Table three below outlines the differences in the types of take-home vehicles.

30

In most cases, an employee must have 12 emergency responses within a 12-month period as one requirement to qualify for a take-home vehicle.

31Other vehicles that generally qualify include unmarked vehicles used by law enforcement officers if the use is officially

authorized, ambulances and hearses, vehicles designed to carry cargo with a loaded gross vehicle weight over 14,000 pounds, school buses, along with other vehicles.

P a g e 15 OOffffiicceeoofftthheeAAuuddiittoorr

Reimbursement exemptions are not consistently applied by the

Department of Safety Table 3 – Summary of Take-Home Vehicle Types

Types of Take-Home Vehicles

Take-Home Vehicle Qualified Non-Personal Use Vehicle

Full Use Safety Vehicle Regulation

Sources

I.R.S. Code, Fiscal Rule and Executive Order

I.R.S. Code, Fiscal Rule and Executive Order

Fiscal Rule and Executive Order Who Qualifies Those required to

commute in the vehicle for a non-compensatory business reason.

Vehicles generally including clearly marked police and fire vehicles and unmarked vehicles used by law enforcement officers. Employee's assignment requires immediate response to emergency situations on a 24-hour on-call basis. Who Authorizes

Agency Head Agency Head Agency Head and Manager of Safety Special

Conditions

Users must respond to 12 emergencies in a 12 month period outside of normal hours, submit trip logs accounting for commuting mileage and reimburse the City for commuting usage.

Users must respond to 12 emergencies in a 12 month period outside of normal hours, but are exempt from

tracking/reimbursing for commuting.

Users are exempt from emergency response quotas and

tracking/reimbursing for commuting.

Audit work identified several issues with the application of these exemptions within the Department of Safety. First, all of DPD’s approximately 250 take-home vehicles are full use safety vehicles; however, no vehicles sampled had the required Manager of Safety authorization. In addition, on the authorization forms received there was no designation for the Manager of Safety’s approval signature.

Audit work also found that guidance surrounding the application of these exemptions is insufficient and the compliance with such guidance is inconsistent. For example, since all of DPD’s take-home vehicles are classified as full use safety

vehicles, personnel using them do not reimburse the City for commuting. Conversely, both DFD and Sheriff Department (Sheriff) personnel reimburse the City for their commuting usage, even though they are generally assigned take-home vehicles for the same reasons as DPD personnel.32 This apparent inconsistency demonstrates that the

exemptions provided by the I.R.S. Code, Fiscal Rule and Executive Order are not being applied consistently for all departments under the authority of the Manager of Safety for vehicles being used for very similar purposes.

32

P a g e 16

C

CiittyyaannddCCoouunnttyyooffDDeennvveerr

It is questionable whether or not attending meetings and employee convenience is justification for taking a City

vehicle home

Additionally, the justification provided on some DPD take-home vehicle authorization forms is out of compliance with the City’s Fiscal Rule and Executive Order. For example, one DPD take-home vehicle authorization form states such a vehicle assignment is justified when an employee, "is required to attend numerous meetings, many fall outside normal shift hours making it impractical for this person to pick up and drop off a company vehicle.” However, both the Fiscal Rule and Executive Order state that full use public safety vehicles can only be authorized for situations where the employee's assignment requires immediate response to emergency situations on a 24-hour on-call basis, requiring the use of specialized safety or emergency equipment. It is questionable whether or not attending meetings and employee convenience is justification for taking a vehicle home or for designating City vehicles as a full use public safety vehicle.

Further, many justifications provided on DPD take-home vehicle authorization forms conflicted with justifications reported by the Department to the Budget and Management Office (BMO). BMO’s list of take-home vehicle assignments is the only comprehensive citywide record of this information. Although, take-home vehicles make up only a small component of the overall budget for each agency, the take-home vehicle information reported is used in making budget decisions. BMO evaluates vehicle utilization on an annual basis and provides this analysis to agencies for management decision making. As noted, in 2010, the BMO addressed significant City budget issues in part by deferring fleet purchases. The failure to provide accurate information to BMO means take-home vehicle assignments cannot be properly assessed and figured into these types of critical budget decisions and agency management vehicle utilization decisions. The BMO’s listing is also the only form of take-home vehicle oversight beyond the agency level.33

In addition to these issues, audit work identified one instance where a DPD take-home vehicle was not parked at the work location when the employee was on vacation at the time. According to the current DPD Collective Bargaining Agreement, an employee cannot be on-call while on vacation. Since one requirement for a full use public safety vehicle is being on-call on a 24 hour basis, the vehicle should have been parked at the work location while the assigned officer was on vacation.34

Lack of Monitoring and Enforcement Create Several Negative Effects

Audit work determined that there is little oversight and monitoring over take-home vehicles, which is the primary cause of the violations and inconsistencies discussed above. Because of the lack of monitoring, clarity and enforcement of regulations, the

33

As noted in the background, the City has an informal Utilization Committee that periodically reviews vehicle usage. However, this committee does not review take-home vehicle assignments.

34

When auditors inquired further about the work schedules of the other DPD employees in the testing sample, all the employees were reported to be always on-call. This was despite an interview that was conducted earlier in the audit where DPD reported that on-call schedules rotate and that vehicles are not taken home when they are not on-call to comply with “full use public safety vehicle” requirements.

P a g e 17 OOffffiicceeoofftthheeAAuuddiittoorr

There may be missed opportunities to eliminate some

take home vehicles, which would reduce City costs

City is out of compliance with the I.R.S Code of Federal Regulations, Fiscal Rule 10.6, and Executive Order 25 pertaining to take-home vehicles. There are several negative effects resulting from non-compliance with these regulations, including:

Since proper controls and guidance do not exist over documenting take-home vehicle usage, processing payroll deductions and applying reimbursement exemptions, the City is not recovering all funds associated with take-home vehicles. These unidentified and uncollected commuting reimbursement funds could be allocated to help fund other City activities.

Without accurate and adequate

documentation of take-home vehicle assignments and justifications, the City is prevented from adequately reviewing and assessing vehicle assignments and utilization. As a result, there may be missed

opportunities to eliminate some take-home vehicles that are not necessary to city operations. Reducing the amount of take-home vehicles would result in reduced costs to the City for vehicle maintenance, fuel and other vehicle related expenses.

The lack of documentation over take-home vehicles may create a negative perception that the City is not transparent about personal use of City assets. Additionally, inconsistent enforcement of reimbursement requirements results in inequities between personnel assigned take-home vehicles. Additional documentation would provide more control over take-home vehicles and would enhance transparency and accountability over take-home vehicles.

RECOMMENDATION

We offer the following recommendation to improve accountability and strengthen internal controls over take-home vehicles.

1.1 The Controller’s Office should revise Fiscal Rule 10.6 to include:

a. Specific requirements regarding "full-use safety vehicle" and "qualified non-personal use vehicle" to ensure consistent application for all Safety departments. This should include language on how these exemptions apply to other City agencies as well.

b. Specific requirements to ensure reimbursement is remitted to the City by personnel for take-home vehicle usage. Specifically, requirements should address full-time and intermittent usage, a method to monitor usage and

P a g e 18

C

CiittyyaannddCCoouunnttyyooffDDeennvveerr

circumstances when the annual lease value method35 would be imposed

after failing to submit required trip logs.

1.2 The Mayor should revise Executive Order 25 to formalize the existing Utilization Committee and require that:

a. The Committee consists of representatives from the Department of Safety, PWs, the Mayor’s Office, Budget and Management, and other agencies at the Mayor’s discretion.

b. The Committee meet annually to consider the most recent take-home vehicle reports submitted by agencies prior to budget finalization.

c. The Committee review take-home vehicle usage for each agency and make policy and budget adjustments as necessary.

d. The Committee be given specific authority to approve or deny take-home usage based on Fiscal Rule and Executive Order requirements.

1.3 The Department of Safety should create policies and procedures to ensure compliance with take-home vehicle requirements. These procedures should include:

a. A process to review the appropriateness of take-home vehicles across all departments under the Department of Safety to ensure that only those take-home vehicles that meet the requirements of qualified non-personal use and full use public safety vehicle are authorized and documented. b. Requirements to ensure that all authorizations are completed properly,

including the Manager of Safety’s signature authorizing “full use public safety vehicles” and providing adequate justifications for take-home use that demonstrate the benefit to the City and the need for the vehicle.

35

The annual lease valuation method uses the fair market value of the employer-provided vehicle for the year utilized to determine the annual lease value, as defined by I.R.S.

P a g e 19 OOffffiicceeoofftthheeAAuuddiittoorr

FINDING 2

Fuel Access Internal Controls are Inadequate

The Fleet Management Division within Public Works (PW Fleet) is responsible for negotiating fuel prices as well as purchasing and distributing fuel. As part of this responsibility, PW Fleet manages and maintains an information system, FuelForce, which is used to control fuel access at fueling locations throughout the City.

To obtain access to fuel at a City fueling location, employees must first obtain a fuel identification (ID) number from PW Fleet. In order to obtain a fuel ID, PW Fleet requires the employee’s supervisor to email PW Fleet with the person’s name and agency. To obtain access to fuel, the person must enter their ID number, the required fueling information and the fuel pump number into a key pad at the fueling site that is linked with FuelForce. Fuel usage is billed to agencies monthly based on the vehicle number fueled.

Audit work found that a lack of internal controls over the process to obtain and terminate access to fuel creates a significant risk that unauthorized fueling could occur. More specifically, inadequate maintenance and management of the FuelForce database has increased the risk for fraudulent activity.

Significant Weakness in Controls of Fueling Database

Auditors obtained a listing of all active fuel ID numbers for all City agencies from FuelForce and selected two samples for testing. The first sample of 81 IDs was selected at random from the list of 8,381 active fuel IDs. Audit work revealed that 37% of the active fuel IDs sampled belonged to terminated employees with two of the IDs showing fueling activity after termination. Additionally, as illustrated in Table 3 below, 22% of active fuel IDs sampled have never been used raising the question of why they are necessary.36

Table 3 – Test 1 Results

Test #1 Results

Fuel IDs assigned to terminated employees Fuel IDs used after terminationFuel IDs never used

30 of 81 (37%) 2 18 of 81 (22%)

The second audit sample consisted of duplicate names selected from the active fuel ID listing. There were at least 750 duplicate names in the fuel ID listing. We reviewed 23 sets

36

Due to the way authorization records are kept by Fleet, it was impossible to determine why IDs were issued and never used. It could be a combination of factors that include, incorrect ID numbers issued, the ID was not needed, the employee

P a g e 20

C

CiittyyaannddCCoouunnttyyooffDDeennvveerr

Significant opportunities exist for improving fuel access

controls

of duplicates and identified that multiple fuel IDs were assigned to 13 employees, with one instance of fueling activity after termination of employment, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4 – Test 2 Results

Test #2 Results

Multiple fuel IDs issued to one person Multiple fuel IDs showing fueling activity Fuel IDs active after employment end 13 of 23 (56%) 1 of 23 137The results of this testing identified several weaknesses in the integrity of the database. In both samples, it is apparent that the process to deactivate fuel IDs after an employee ceases to work for the City is a significant control failure. The termination dates of some of these employees in the sample date back to 1990. This control failure is especially important since fuel IDs may have been inappropriately used after employees have left the City.38 Specifically, audit work found that approximately 1,603 gallons of fuel were

obtained with fuel IDs belonging to terminated City employees. Evidence obtained during the audit could not prove or disprove that this fuel was obtained fraudulently, partially due to the lack of video cameras at fueling stations.39 These results are also

particularly alarming, given that the overall sample of fuel IDs tested was approximately 1% of all active IDs in FuelForce. As a result, the risk exists for substantive fraud.

In addition, auditors observed that sometimes nicknames and middle names are given to obtain

fuel access, which made tracking down

employment history difficult. In some instances, no first name was given to obtain fuel access. There was also one case where an active fuel ID with a fueling history as recent as September 2010 was from an ID of a person that has no record of employment with the City, when compared to PeopleSoft and CSA Records.40

Several Factors Contribute to Poor Controls Over Fuel Access

The process to obtain and terminate fuel access is very informal, which has led to many of the problems described above. First, requesting access to fuel through an email does not provide PW Fleet with a way to track who is granting access to fuel and the information gathered about the driver is often inconsistent and incomplete. Further, steps

37

This employee was laid off in 2004 and the ID number remained active at the time of testing. This ID was used as recently as September 2010 to obtain fuel. Auditors could not determine if this fuel was obtained fraudulently.

38

Auditors did not obtain any strong evidence to support the terminated employees were the ones using the fuel IDs after the end date of employment.

39

At the time of the audit, only two fueling sites had video cameras and footage was only kept for the ten previous days. 40

It is possible that this person did not give a correct or full name to Fleet at the time the ID was created or that the person is employed with a quasi-governmental agency and the department associated with this ID was improperly entered.

P a g e 21 OOffffiicceeoofftthheeAAuuddiittoorr

are not taken to verify if the person requesting access is indeed the employee’s supervisor. In addition, if an error is found in a fuel ID, a new one is issued rather than correcting the error, which is partially the reason why there are so many duplicate names in the active fuel IDs.

For terminating fuel access, PW Fleet currently relies upon the agencies to notify them about employee separation from the City, which often does not happen. Fleet will send an annual reminder memo to agencies reminding them to report any terminations. However, no additional steps are taken by PW Fleet to ensure only current employees have active fuel IDs.

RECOMMENDATIONS

We offer the following recommendation to strengthen internal controls regarding the management of the Fuel Force system.

2.1 The Fleet Management Division should create a formal process to grant and terminate access to fuel which includes:

a. Developing policies and procedures for the process including a standardized form that requires agency information, employee full name and ID number and supervisor signature.

b. Using employee ID as the fuel ID to eliminate duplicates and create an audit trail.

c. Requiring edits to a fuel ID if an error is found rather than creating a new ID.

d. Performing regular reconciliations between PeopleSoft records and the active fuel ID list to remove terminated employees. At a minimum, these reconciliations should be performed every six months.

e. Requiring annual positive confirmations from all entities with fuel access regarding validity and necessity of fuel users. This confirmation should include language stating the fuel user will protect the fuel ID and notify Fleet in the event their fuel ID is compromised.

2.2 When the Fleet Management Division invoices agencies for fuel usage, the invoice detail should include the name associated with the fueling ID used to fuel each vehicle so the agencies can review for appropriateness.

2.3 The Fleet Management Division should install video cameras at all fueling sites and consider obtaining additional data storage to allow for a minimum of 60 days of footage available for review.

P a g e 22

C

CiittyyaannddCCoouunnttyyooffDDeennvveerr

FINDING 3

Opportunities Exist to Improve Parts Inventory Controls

An essential component of fleet management is effective control and management of parts inventory. Inventory is considered an asset and must be adequately maintained, meaning that inventory should be monitored throughout the life of the part from receipt of the inventory to disbursement for repairs or returns to the vendor for credit.

Best Practice Identified for Parts Inventory Control

Last year PWs Fleet Management commissioned Laird Consulting to perform a Lean Process Review of their parts operation.41 The review focused on inventory control,

storerooms, staffing, processes and procedures, and customer service. The results of the study strengthened controls regarding the management of parts inventory. This study and the new FASTER system has allowed PWs to improve their inventory operating procedures to better monitor parts inventory while keeping costs to a minimum without compromising customer service.42

One basic inventory control used by PW Fleet is securing the parts room behind a locked door allowing only authorized personnel to enter. All parts activity, whether it is shipping or receiving, cycle count audit adjustments, or work order requests is tracked in the FASTER system. Each part is assigned a unique number and a corresponding barcode that is used to monitor the movement of the part throughout the part’s life cycle. For example, when a part is required for repairs and maintenance, it is scanned and relieved from inventory before it leaves the parts room. This action ensures the custody of the part is monitored at all times.

Cycle counts are completed during each quarter in addition to a yearly physical inventory count to ensure that inventory on hand is accurate and stocking issues can be resolved timely.43 Handheld units are used to complete both the cycle counts and the

annual inventory. The 2009 annual physical inventory resulted in an adjustment of $1,151.40 or 0.07% of total inventory value.44

Tracking all parts activity in FASTER and incorporating the recommendations of the Lean Process Review has allowed the PW parts manager to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the parts operations. Because of this, we consider PWs inventory operating procedures to be an internal best practice that Denver Police and Denver Fire Departments could leverage within their parts operations.

41

A Lean Process Review is design to reduce waste, improve processes and incorporate best practices common within the industry.

42

Public Works Fleet Maintenance operates all satellite facilities with the same policies and procedures. 43

A cycle count is an inventory management technique designed to maintain the accuracy of inventory on hand with the amount recorded in the system.

44

P a g e 23 OOffffiicceeoofftthheeAAuuddiittoorr

Weakness in Department of Safety Parts Inventory Controls

Audit work determined that a lack of internal controls over the parts inventory processes at the DPD and DFD leads to inaccurate on-hands and inventory valuation, inventory out-of-stocks and overstock, increased levels of obsolete and slow moving inventory, and creates significant risk of asset misappropriation.45

The stockroom supervisor is responsible for the organization, shipping and receiving, purchasing, part management, and inventory procedures for the parts room. The FASTER fleet management system is used by both DPD and DFD to manage inventory. All parts are assigned a unique number and barcode that is used to monitor part activity in the system for the life of the part, but the DPD and DFD have not fully implemented the barcode option of the system in contrast to PW. DPD has assigned barcodes to each part number but has not started using the handheld units and DFD has yet to assign barcodes to each part. Officials from both Departments identified resources constraints as the rational for not fully integrating the barcode method to monitor and track inventory. Both departments operate their parts room with limited resources; the DPD parts room consists of two employees, a supervisor and an assistant, and DFD only has one full-time parts manager.

Audit work included a test of DPD and DFD parts inventory for accuracy by choosing 10 parts randomly from the shelf and verifying the on-hand parts in the system and choosing another 10 parts from the system and verifying the on-hand shelved parts.46 Both types of

tests were combined to get the total amount of accurate on-hand parts. Results for DPD indicated that 8 (40%) of the on-hand parts tested were not accurate and 10 (50%) of the on-hand parts tested for DFD were not accurate. The majority of these differences resulted from parts not charged to a work order and parts not returned to stock when they were pulled but subsequently not used for a work order.47

Several Factors Contribute to the Weak Inventory Controls

The failure to utilize the inventory system as designed is the main factor hindering the ability of DPD and DFD to effectively monitor and track inventory. For example, parts issued to DPD mechanics are not removed from the system when issued; but instead are tracked on a manual log. Mechanics and the Parts Department personnel reconcile the parts used in work orders to the hand written log when repairs are complete rather than within the automated system.

Similarly, the one full-time DFD parts manager cannot be in the parts room at all times and the door is not secure allowing for unauthorized access to the parts room. The individual retrieving a part is “on their honor” to write down the item in a notebook or on a form that the DFD parts manager uses to update the system. If a part taken from the parts room is not recorded on the notebook or form, the inventory is not updated. In addition to the lack of security over the parts room, the lack of resources for both Departments has impacted cycle counts, which are not being completed regularly. On

45

The Denver Police Department also repairs all Denver Sheriff Department vehicles. 46

The sample from the system was judgmentally selected choosing parts that had an on-hand recorded. 47

P a g e 24

C

CiittyyaannddCCoouu