Munich Personal RePEc Archive

Corruption and health expenditure in

Italy

Lagravinese, Raffaele and Paradiso, Massimo

University of RomaTre, University of Bari

2 December 2012

Corruption and health expenditure in Italy

Raffaele Lagravinese

∗University of Roma Tre

Massimo Paradiso

University of Bari

December 2, 2012

Abstract

The vulnerability of health sector to corruption lies in the complex interaction between the social environment and the institutional set-ting of health systems. We investigate this interaction in the case of Italy, specifically looking at the impact of corruption on health expen-diture. In Italy corruption is a social phenomenon. Health sector has been often involved in corruption offences and decentralized health ex-penditure is considerably out of control. We show that the impact of corruption on health expenditure is positive, along with ageing pop-ulation, technological change and supply factors inducing demand in pharmaceuticals and hospitalization. Moreover, the empirical analy-sis demonstrates that corruption affects pharmaceutical expenditure and accredited private hospital expenditure, suggesting implications for health governance and policy.

Keywords: health expenditures, corruption, panel data, sur model.

∗Corresponding author. email: raffaelelagravinese@uniroma3.it; Address:77 S.D’Amico

1

Introduction

In recent years a growing literature [surveyed in 1, 2] has investigated the effects of corruption on the health sector. In developing and transitional economies corruption lowers the quality of health care, limits the access to health services and increases health expenditure. The general framework of the determinants of corruption in public administration [3] is consolidated by specific features of health sector: inelastic demand for health services, high degree of asymmetric information, large variety of interacting actors (regula-tors, payers, public and private providers, consumers) with opposite interests. Several papers have showed how these features enhance corrupted practices in the different sectors of the health care; and it has been argued that the oc-currence of corruption finds a favorable environment where social norms are weaker and corrupt practices are tolerated or even justified [2-6]. Corruption in health sector is a phenomenon in which social environment, health gov-ernance and financing are intertwined. Centralized or decentralized health financing may enhance different levels of corruption, since different are the levels of financial accountability. Public participation and local accountabil-ity of public resources are in theory higher in decentralized than in centralized fiscal systems [7]. In corrupted social environments the decentralization may improve health outcomes [8, 9]; but it may also foster corruption [10], due to the lacking of adequate institutional checks and balances at local level.

and health sector is involved in corruption offences. In Italy, corruption is rooted in political and economic history and its evolution has paralleled the growth of public expenditure, culminated in the 1980’s. The impressive emergence of corruption scandals in politics and public administration during the 1990’s, overwhelmed the political system and favored the demand for an institutional change in the direction of the decentralization and fiscal federal-ism [13-17]. A relevant step toward decentralization was taken in the health sector, that had not been immune from corruption scandals [18], following a process aimed at improving the performance and constraining the costs of health care. But decentralization has not controlled health expenditure and has not prevented health sector from corruption. Health expenditure amounts to 9.1% of GDP in 2008 and counts on average for 75 % of regional public expenditures. The large amount of public resources and the inade-quacy of regional health governance have made the health sector particularly exposed to corruption, whose impact on health expenditure has been often stressed by the national audit office [19, 20].

The purpose of this paper is to empirically investigate this impact in the decade from 1998 to 2008. The investigation has been conducted on total health expenditure and on its four main categories (pharmaceutical, primary care, inpatient and accredited private hospital), focusing on the influence of corruption along with demographic factors, per capita GDP and health care inputs. Our results highlight the role of corruption as a determinant of accredited private hospital expenditure and pharmaceutical expenditure, suggesting implications for health governance and policy.

2

Health system and expenditure in Italy

The Italian National Health Service (NHS), founded in 1978, is a univer-sal health care system providing comprehensive health insurance coverage and uniform health benefits to the whole population. In the last 15 years the Italian NHS has undergone, like other European countries, important reforms [21], in the direction of decentralization of health management and policy responsibilities to the sub-layers of government –21 administrative jurisdictions, specifically 19 regions and two autonomous provinces. In 1999, the reform of NHS introduced the essential levels of health services (ELS), defined and financed by central government and provided by regional author-ities. Since then regions have developed relatively different health systems, characterized by different mix of public and accredited private hospitals. The accreditation of private hospitals aims at reducing the monopoly power of public providers and improving efficiency of health services, with a re-imbursement scheme based on Diagnostic Related Groups (DRG) applied to both public and accredited private hospitals. The 2001 Constitutional reform has assigned the health sector to regional competency, but with rele-vant regulating and financing functions maintained by the central government [22,23]. As result of this contradictory reform, Italian regions are required to spend enough to provide ELS, while central government is required to fi-nance regions enough to provide ELS. Bailing out expectations from central government and the separation of financing responsibilities from expenditure responsibilities have been considered a relevant stimulus for the uncontrolled growth of Italian health expenditure [24-28] in a context of often inadequate regional health governance and accountability [29-31].

in 2001 additional central government funds were allocated to cover NHS deficits accumulated since 1994; and in 2005, further central government funds were allocated to cover NHS deficit and regions, unable to contain deficits, underwent (centrally monitored) budgetary balance plans, whose effectiveness has been questioned [32,33].

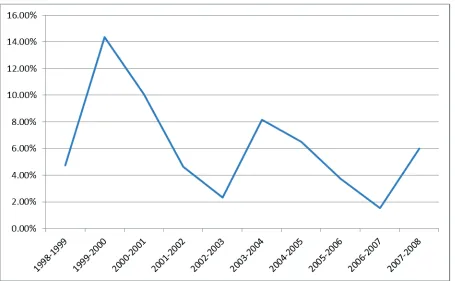

(F IGU RE 1)

3

The data

The empirical investigation of the determinants of Italian health expenditure is based on a yearly panel data set for the 21 administrative jurisdictions for the period 1998-2008. We collected data on public health system from "Health for All" dataset [34] of Italian National Account. The public admin-istration corruption rate has been gathered from Information system on jus-tice [35]. In the first part of our analysis we consider as dependent variable the total per capita public health expenditure (TOT_HE). We first control for the basic determinants of public health expenditure: health care activity in-puts, such as doctors rate (TOT_DOC) and beds rate (TOT_BEDS); time, as a partial proxy for technological change (TIME);and socio-economic vari-ables, such as regional per capita GDP (GDP), population density (DENS) and population over 65 (POP_65). Finally, we specifically control for cor-ruption rate (COR). By following Del Monte and Papagni [17], corcor-ruption is defined as the rate of crimes against public administration at regional level. The number of crimes against public administration are based on statutes of the ISTAT-Annals of Judicial Statistics1. In the second part of the analysis

we divide the total health expenditure into four main components: phar-maceutical (PHARM), primary care (PRIM), inpatient (INP), accredited

private hospital (PRIV). As shown in table 1, per capita pharmaceutical is the largest expenditure category (183 euros); followed by accredited private hospital (93.4 euros), primary care (87.3 euros) and inpatient (43.6 euros) expenditures.

In addition to the above listed determinants, we control each component of the spending for specific health care inputs: medical prescriptions (PRES), general practitioners (GP_DOC), physicians (PHYS_DOC), private special-ists (PRIV_DOC) and private beds (PRIV_BEDS).

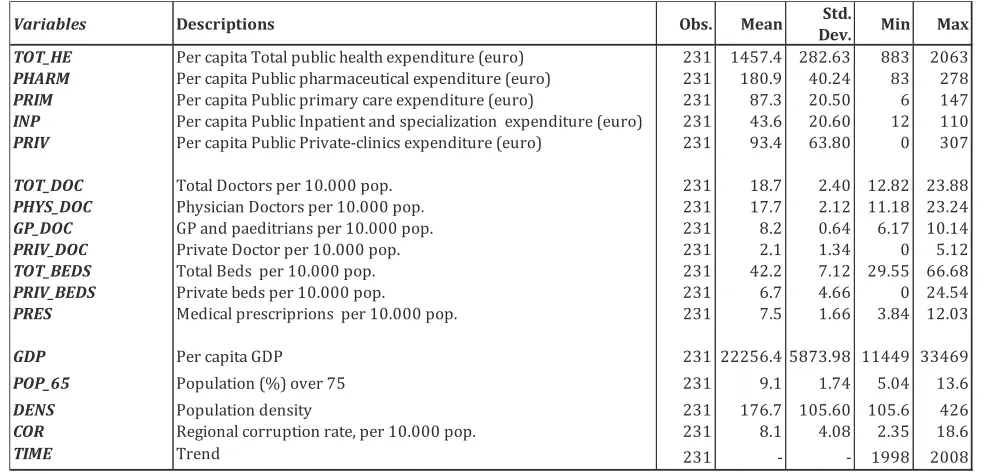

Variable definitions and summary statistics are given in table 1.

4

Empirical model

The empirical analysis has been conducted in two steps. Initially, we have used a single-equation approach with fixed and random effects to examine whether the variable of interest (i.e corruption) is significantly correlated with public health expenditure, after controlling for basic determinants of health spending (such as regional Income, ageing, population density, doctors and beds). In the second step, we have adopted a Seemingly Unrelated Regression (SUR) to estimate the impact of corruption on the four main components of public health expenditure in Italy: pharmaceutical, primary care, inpatient and accredited private hospitals.

Tthe basic econometric specification [36] is the following:

lnT OT_HEit=αi+β1lnGDPit+β2lnP OP_65it+β3lnT OT_BEDit+ (1)

+β4lnT OT_DOTit+β5lnDEN Sit+β6lnCORit+β7T IM Eit+εit

Where the subscripts i stands for region andt for time.

The dependent variable, total per capita public health expenditure, is re-gressed on the standard socio-economic variables (such as income, population ageing and density), corruption and the time trend. All variables are taken in natural logarithms, allowing us to consider the estimated coefficients as elasticities.

lnP HARMit= αi+β1lnGDPit+β2lnP OP_65it+β3lnT OT_BEDit+ (2)

+β4lnT OT_DOTit+β5lnP RESit+β6lnDEN Sit+ lnCORit+β7T IM Eit+εit

ln P RIMit=αi+β1lnGDPit+β2lnP OP_65it+β3lnT OT_BEDSit+ (3)

+β4lnGP_DOCit+β5lnDEN Sit+β6lnCORit+β7T IM Eit+εit

lnIN Pit=αi+β1lnGDPit+β2lnP OP_65it+β3lnT OT_BEDSit+ (4)

+β4lnP HY S_DOCit+β5lnDEN Sit+β6lnCORit+β7T IM Eit+εit

lnIN Pit=αi+β1lnGDPit+β2lnP OP_65it+β3lnP RIV_DOCit+ (5)

+β4lnP RIV_BEDSit+β5lnDEN Sit+β6lnCORit+β7T IM Eit+εit

Note that to obtain more robust estimates, we have investigated the impact of corruption after controlling in each component of the spending for specific covariants: medical prescriptions (PRES), general practition-ers (GP_DOC), physicians (PHYS_DOC), private specialists (PRIV_DOC) and private beds (PRIV_BEDS).

5

Results and discussion

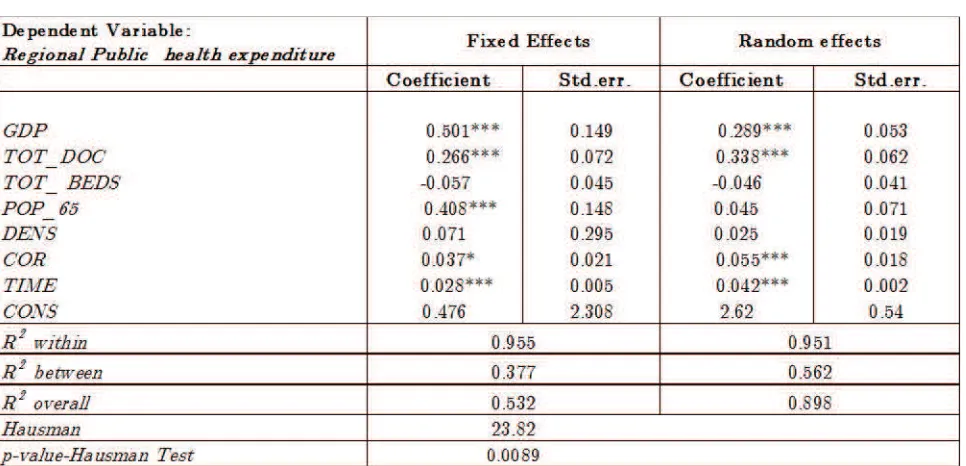

coefficients between the two models are not systematic, thus implying that the random-effects (GLS) model is to be preferred. Therefore, the following comments are based on the results obtained with the GLS.

Our findings confirms that in Italy [38] ageing population is a relevant determinant of health expenditure. In line with previous studies [36, 38-41], the doctor rate and beds rate impact positively on health expenditure, sug-gesting a supply induced demand for health services. Our estimates support the observation that health expenditure is not a luxury good [42]; however, income is positive and statistically significant. This result implies an income effect, suggesting that, despite the universality of Italian health care system, the (formally equal) access to health care services is not independent from income and possibly related to the different regional models of health de-centralization. Time trend, interpreted as a partial proxy for technological change, is positive and statistically significant. This result confirms the ob-served evidence of the impact of technology on health expenditure [43,44]. Finally, the impact of corruption on health expenditure is positive and sta-tistically significant. This is a relevant result, which requires further specifi-cations: since the impact of corruption is expected to be different among the components of health expenditure.

(T ABLE 2)

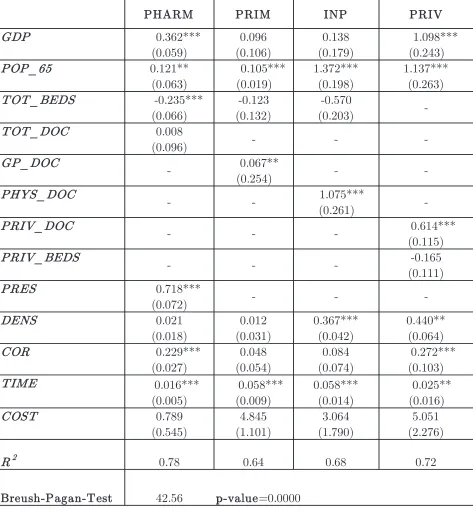

Table 3 shows the results of the SUR model with an R2

=0.78 for the pharmaceutical expenditure, 0.64 for primary care expenditure, 0.68 for in-patient expenditure and 0.72 for accredited private hospitals expenditure, all indicating a good fit.

popu-lation density only impacts on inpatient and accredited private hospital ex-penditures. The number of beds exerts a negative impact on pharmaceutical expenditure. A similar result has been found also in the case of Spain [46]. The coefficients of physicians, general practitioners and private specialists are positive and statistically significant respectively on impatient, primary and accredited private hospital expenditure, thus implying a supply induced demand of hospitalization. As expected the prescriptions rate is positively related to pharmaceutical expenditure. Technological change confirms its impact: time trend is positive and statistically significant.

Our findings implies that corruption in health system is sectorial. The estimated impact of corruption is positive for all the components of health expenditure, but statistically significant (99% confidence level) only for phar-maceutical expenditure and accredited private hospital expenditure. These results appear to reflect the link between corruption and the institutional setting of Italian health system. Regional health systems are characterized by different mix of public and private accredited hospitals. Nevertheless, this form of competition has not prevented corruption and has showed an elusive impact on efficiency [47], suggesting that performances are dependent from the institutional setting in which hospitals operate. That is, more in general, from the governance and regulation of regional health systems, often lacking adequate monitoring and accountability procedures of health services provi-sion. In this respect, our estimation result on the impact of corruption on accredited private hospitals expenditure supports the observation that pri-vatization of health services does not reduce corruption in the health sector when public systems of regulation and control of private care and treatments are inadequate or lacking [11].

collu-sion between the involved actors [48-52]. In Italy, after the involvement in corruption offences, the pharmaceutical sector was reformed in 1993. Co-payments schemes were introduced and from 2001 a new pricing scheme has split the pharmaceutical market into two groups, according to the patent situation and recognizing “premium prices” for innovative drugs. Recent studies [53,54] show that this scheme incentives the promotion of products more expensive and still under patent protection, whose consumption is a relevant driver of Italian pharmaceutical expenditure, in a context of weak regional policies of control on prescribing behaviors [20-55].

(T ABLE 3)

6

Conclusions

sector is in appropriate systems of governance, monitoring and transparency of the health care delivery process.

References

[1] Lewis M. Governance and Corruption in Public Health Care Systems. Working Paper 78; Washington, Center for Global Development 2006.

[2] Vian T. Review of corruption in the health sector: theory, methods and interventions. Health policy and planning 2008; 23:83-94.

[3] Aidt TS. Economic Analysis of Corruption: A Survey, Economic Journal , 2003; 113:F632-F652.

[4] Ensor T, Antonio DM. Corruption as a challenge to effective regula-tion in the health sector. In: Saltman RB, Busse R, Mossialos E, (eds). Regulating entrepreneurial behavior in European health care systems. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press; 2002.

[5] Duncan F. Corruption in the health sector. Washington,DC: USAID Bureau for Europe & Eurasia, Office of Democracy and Governance; 2003.

[6] Savedoff WD. The causes of corruption in the health sector: a focus on health care.systems. In: Transparency International. Global Corrup-tion Report 2006: Special focus on corrupCorrup-tion and health. London: Pluto Press; 2006.

[7] Oates WE. An essay on fiscal federalism, Journal of Economic Literature 1999; 37:1120-1149.

[8] Robalino D, Picazo O, Voetberg A. Does Fiscal Decentralization Im-prove Health Outcomes? Evidence from a Cross-Country Analysis, Policy research working paper series 2565; World Bank 2001.

[10] Khaleghian P, Das Gupta M. Public management and the essential pub-lic health functions. World Development 2005; 33:1083-1099.

[11] Gupta S, Davoodi H, Tiongson E. Corruption and the provision of health care and education. IMF Working Paper 00/116; Washington, DC 2000.

[12] Azfar O, Gurgur T. Does corruption affect health outcomes in the Philip-pines?, Economics of Governance 2008; 9: 197-244.

[13] Della Porta D, Vannucci A. Corrupt exchanges: Actors, resources and mechanism of political corruption. New York: Aldine de Gruyter 1999.

[14] Della Porta D, Vannucci A. Mani Impunite. Vecchia e nuova corruzione in Italia. Bari, Laterza 2007.

[15] Golden M A. Electoral connections: the effects of the personal vote on political patronage, bureaucracy and legislation in postwar Italy. British Journal of Political Science 2003; 33: 189—212.

[16] Del Monte A, Papagni E. Public expenditure, corruption, and economic growth: the case of Italy. European Journal of Political Economy 2001; 17:1-16.

[17] Del Monte A, Papagni E. The determinants of corruption in Italy: Re-gional panel data analysis. European Journal of Political Economy 2007; 23: 379-396.

[18] Fattore G, Jommi C. The new pharmaceutical policy in Italy, Health Policy 1998; 46: 21- 41.

[19] Corte dei Conti. Relazione sulla gestione finanziaria delle regioni: eser-cizi 2004-2005 (deliberazione 14/2006), Rome 2006.

[21] France G, Taroni F, Donatini A. The Italian health-care system. Health Economics 2005; 14:187-202.

[22] Cappellaro G, Fattore G, Torbica A. Funding health technologies in decentralized systems: a comparison between Italy and Spain, Health Policy 2009; 92: 313-321.

[23] Ferrario C, Zanardi A. Fiscal decentralization in the Italian NHS: what happens to interregional redistribution?. Health Policy 2011; 100: 71-80.

[24] Liberati P. Fiscal federalism and national health standards in Italy: implications for redistribution. In: I sistemi di welfare tra decen-tramento regionale ed integrazione europea, Franco D, Zanardi A. (eds). Franco Angeli 2003; 241—73.

[25] Mosca I. Is decentralisation the real solution? A three country study. Health Policy 2006; 77: 113-120.

[26] Tediosi F, Gabriele S, Longo F. Governing decentralization in health care under tough budget constraint: What can we learn from the Italian experience? Health Policy 2009; 90: 303—312.

[27] Bordignon M, Turati G. Bailing out Expectations and Public Health Expenditure, Journal of Health Economics 2009 ; 28:305-321.

[28] Citton A, Liberati P, Paradiso M. Il percorso del federalismo fiscale in Italia. In: La finanza locale: struttura, finanziamento e regole, Degni M. and Pedone A. (eds.). Franco Angeli 2010; 219-238.

[29] France G, Taroni F. The evolution of Health-Policy Making in Italy. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 2005; 1-2:169-184.

[31] Carinci F, Caracci G, Di Stanislao F, Moirano F. Performance mea-surement in response to the Tallinn Charter:Experiences from the decentralized Italian framework 2012; 108: 60-66.

[32] Tediosi F, Paradiso M. Il controllo della spesa sanitaria e la credibilità dei Piani di rientro. in Rapporto ISAE - Finanza pubblica e Isti-tuzioni, Roma 2008.

[33] Ferrè F, Cuccurullo C, Lega F. The challenge and the future of health care turnaround plans:Evidence from the Italian experience. Health Policy 2012; 106: 3-9.

[34] ISTAT. Health For All 2012. ISTAT 2012.

[35] ISTAT. Information system on justice. ISTAT 2012.

[36] Gerdtham UG, Jonsson B. International comparisons of health expendi-ture: theory, data and econometric analysis. In: Handbook of Health Economics, Culyer AJ, Newhouse JP (eds). Elsevier Science Publish-ers: Amsterdam 2000.

[37] Zellner A. An Efficient Method of Estimating Seemingly Unrelated Re-gressions and Tests for Aggregation Bias. Journal of American Sta-tistical Association 1962; 57: 348—368.

[38] Gianonni M, Hittris T. The regional impact of health care expenditure: the case of Italy. Applied Economics 2002; 34:1829—1836.

[39] Di Matteo L, Di Matteo R. Evidence on the determinants of Canadian provincial Government health expenditures: 1965-1991. Journal of Health Economics 1998 ; 17: 211-228.

[40] Crivelli L, Filippini M, Mosca I. Federalism and regional health care: an empirical analysis for the Swiss cantons. Health Economics 2006; 15: 535-541.

2007; 16: 291—306.

[42] Baltagi BH, Moscone F. Health care expenditure and income in the OECD reconsidered: Evidence from panel date, Economic modelling 2010 ; 27: 804-811.

[43] Di Matteo L. The determinants of the public—private mix in Canadian health care expenditures: 1975—1996, Health Policy 2005; 52: 87— 112.

[44] Martin Martin J J, Gonzalez M P, Garcia M D. Review of the literature on the determinants of healthcare expenditure. Applied Economics 2011; 43: 19-46.

[45] Clemente J, Marcuello C, Montanes A. Pharmaceutical expenditure, total health-care expenditure and GDP. Health Economics 2008; 17: 1187-1206.

[46] Lauridsen J, Bech M, López F, Maté Sánchez M. Geographic and Tem-poral Heterogeneity in Public Prescription Pharmaceutical Expendi-tures in Spain. The Review in Regional Studies 2008; 38: 89-103.

[47] Barbetta GP, Turati G, Zago AM. Behavioral differences between pub-lic and private not-for-profit hospitals in the Italian national health service. Health Economics 2007; 16: 75-96.

[48] Kassirer J. The corrupting influence of money in medicine. In: Trans-parency International. Global Corruption Report 2006: Special focus on corruption and health. London: Pluto Press 2006.

[50] Cohen JC, Mrazek M, Hawkins L. Tackling Corruption in the Pharma-ceutical Systems Worldwide with Courage and Conviction, Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 2007; 81: 445-449.

[51] Fidler A, Msisha W. Governance in the pharmaceutical sector. Euro-health 2008; 14: 25-29.

[52] World Health Organization. Measuring transparency in the public phar-maceutical sector: assessment instrument, Geneva, WHO 2009.

[53] Ghislandi S, Krulichova I, Garattini L. Pharmaceutical policy in Italy: towards a structural change?. Health Policy 2005; 72: 53—63.

[54] Gallizzi M, Ghislandi S, Miraldo M. Effects of Reference Pricing in phar-maceutical markets: a review. PharmacoEconomics 2011; 29:17-33.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Variables Descriptions Obs. Mean Std.

Dev. Min Max

TOT_HE Per capita Total public health expenditure (euro) 231 1457.4 282.63 883 2063

PHARM Per capita Public pharmaceutical expenditure (euro) 231 180.9 40.24 83 278

PRIM Per capita Public primary care expenditure (euro) 231 87.3 20.50 6 147 INP Per capita Public Inpatient and specialization expenditure (euro) 231 43.6 20.60 12 110 PRIV Per capita Public Private-clinics expenditure (euro) 231 93.4 63.80 0 307

TOT_DOC Total Doctors per 10.000 pop. 231 18.7 2.40 12.82 23.88

PHYS_DOC Physician Doctors per 10.000 pop. 231 17.7 2.12 11.18 23.24

GP_DOC GP and paeditrians per 10.000 pop. 231 8.2 0.64 6.17 10.14

PRIV_DOC Private Doctor per 10.000 pop. 231 2.1 1.34 0 5.12

TOT_BEDS Total Beds per 10.000 pop. 231 42.2 7.12 29.55 66.68

PRIV_BEDS Private beds per 10.000 pop. 231 6.7 4.66 0 24.54

PRES Medical prescriprions per 10.000 pop. 231 7.5 1.66 3.84 12.03

GDP Per capita GDP 231 22256.4 5873.98 11449 33469

POP_65 Population (%) over 75 231 9.1 1.74 5.04 13.6

DENS Population density 231 176.7 105.60 105.6 426

COR Regional corruption rate, per 10.000 pop. 231 8.1 4.08 2.35 18.6

Table 2. Econometric results: Fixed and Random effects

Table 3.SUR results

The table reports coefficients and standard errors (in brackets) ***;**, * statistically significant at 1%,5% and 10% respectively.

PHARM PRIM INP PRIV

GDP 0.362***

(0.059) 0.096 (0.106) 0.138 (0.179) 1.098*** (0.243) POP_65 0.121** (0.063) 0.105*** (0.019) 1.372*** (0.198) 1.137*** (0.263)

TOT_BEDS '-0.235***

(0.066) -0.123 (0.132) -0.570 (0.203) -TOT_DOC 0.008

(0.096) - -

-GP_DOC

- 0.067**

(0.254) -

-PHYS_DOC

- - 1.075***

(0.261)

-PRIV_DOC

- - - 0.614***

(0.115) PRIV_BEDS

- - - -0.165

(0.111)

PRES 0.718***

(0.072) - -

-DENS 0.021 (0.018) 0.012 (0.031) 0.367*** (0.042) 0.440** (0.064)

COR 0.229***

(0.027) 0.048 (0.054) 0.084 (0.074) 0.272*** (0.103)

TIME 0.016***

(0.005) 0.058*** (0.009) 0.058*** (0.014) '0.025** (0.016) COST 0.789 (0.545) 4.845 (1.101) 3.064 (1.790) 5.051 (2.276)

R2 0.78 0.64 0.68 0.72

Figure 1. Trend of health expenditure in Italy (Var. %)