Demessew Shiferaw and Dr Hailu Hagos

2002

THIS PROJECT IS FUNDED BY

PAN LONDON REFUGEE TRAINING & EMPLOYMENT NETWORK (PLRTEN)

Refugees and progression

routes to employment

Contents

Page

Acknowledgements 4

Foreword 5

List of figures 6

List of tables 6

Acronyms 7

Glossary 8

Executive Summary 9

1. Introduction 10

2. Background 12

3. Aims and objectives 13

4. Methodology 13

4.1 Interview 13

4.2 Questionnaire 13

4.3 Review of prior research 13

4.4 Case studies 13

5. Review of literature 14

5.1 The nature of refugee unemployment 14

5.2 Transition models 17

6. Analysis of refugees’ responses to questionnaire 17

6.1 Characteristic profile of respondents upon arrival 17

6.2 Destinations after arrival 19

6.3 Employment barriers as seen by refugees 21

6.4 Issues within employment 22

6.5 Common pathways to employment 22

7. Analysis of interviews/contact with organisations 28

7.1 Employment barriers as seen by refugee community

organisations and refugee agencies 28

7.2 Overview of existing training and career advice services 31 7.3 Gaps in training, career advice and employment services 34

8. Conclusion and recommendations 38

Bibliography 41

Appendix I: List of agencies interviewed i - ii

Appendix II: Interview questions iii

Appendix III: Sample questionnaire v – viii

Appendix IV: Pathways of questionnaire respondents x - xi

Appendix V: Models of stages and services between arrival & employment xii Appendix VI: Selected case studies of refugee agencies & refugee

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Steve Hill, Co-ordinator of Pan-London Refugee Training & Employment Network, for appointing us to undertake this research and for his support and supervision through-out the project. We are indebted to Gertrud Mûller of Refugee Education and Training Advisory Services for recommending us for this project. We are also grateful to all those refugee and non-refugee agency staff for sharing with us their experience of providing training and guidance services to refugees and asylum seekers and for helping us access their clients. Last but not least, we would like to thank all our respondents for taking their time to complete the questionnaires.

Demessew Shifferaw and Dr Hailu Hagos

Further copies and information

Foreword

The subject of refugees has never been far from the news headlines in the last few years. Yet behind the headlines are the real hardships that asylum seekers and refugees face in trying to settle in the United Kingdom and to use the skills and experience that they may have. At a time when the Government is looking to encourage more economic migration to meet shortages of labour and skills gaps in both the public and private sector it needs to be made clear that refugees have much to offer.

The Government has in some measure acknowledged this through its Refugee Integration Strategy and the Home Office funding regimes designed to assist the integration process, in which access to work and skills development plays an important part.

For refugees to progress into suitable employment there needs to be a greater opportunity for asylum seekers to receive a realistic orientation service about the labour market as well as services such as learning English, receiving information and advice about statutory services and learning about opportunities that education, training and work can bring. There is an opportunity for the proposed accommodation centres for asylum seekers to be developed to provide services such as these. However, doubts will persist that they will be merely processing and holding centres. Where there are time gaps in education and training it can be much harder for people to reuse dormant skills in their new country.

At present much good practice is wasted because of a lack of linkage of different services as well as underpinning support. This report highlights where there is good practice, and suggests how this can be developed. This also has implications for areas outside of London as through the dispersal system more and more asylum seekers settle around the U.K.

Steve Hill

Co-ordinator

List of Tables

Page

Table 1 Employment sectors of those who had employment 18

experience in their country of origin

Table 2 Medium used to find a job 19

Table 3 Career guidance centres used by respondents 20

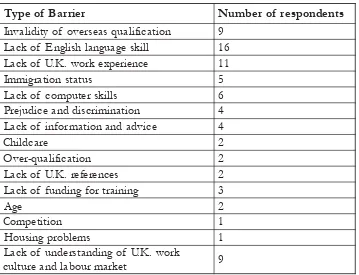

Table 4 Employment barriers as seen by refugees 21

List of Figures

Page

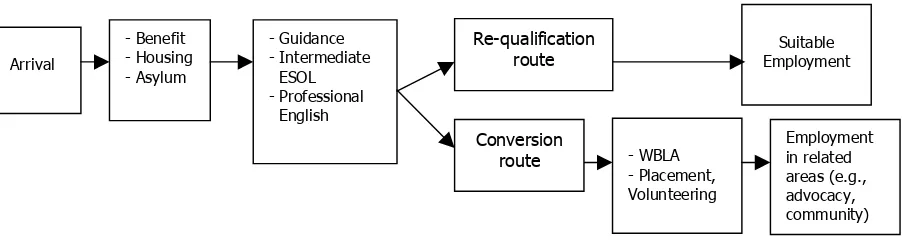

Figure 1 Tony Marshall’s Transition Model 17

Figure 2 Young refugees routes to employment 23

Figure 3 Routes to employment of refugees in regulated

professions 24

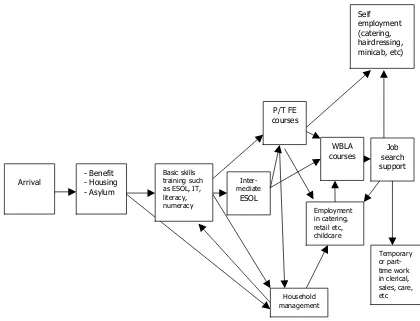

Figure 4 Routes to employment for qualified refugees with

managerial and administrative experience 24

Figure 5 Routes to employment for unqualified refugees 25

Figure 6 Model Pathway 26

Acronyms

AAT Association of Accounting Technicians

AET Africa Educational Trust

APEL Accreditation of Prior Experiential Learning

CDT Community Development Team

ECRE European Council on Refugees and Exiles

ESOL English for Speakers of Other Languages

GNVQ General National Vocational Qualification

IELTS International English Language Testing System

IT Information Technology

NVQ National Vocational Qualification

PLAB Professional and Linguistic Assessment Board

PLRTEN Pan London Refugee Education and Training Network

RAGU Refugee Advice and Guidance Unit

RCOs Refugee Community Organisations

RETAS Refugee Education and Training Advisory Service

RTEC Refugee Training and Employment Centre

(now called TES Training & Employment section)

TES Training and Employment Section of Refugee Council

Glossary

full-time employment over 30 hours of paid work a week

part-time employment less than 30 hours of paid work a week

casual employment paid employment for various employers for a fluctuating length of time

unemployment people who are not in paid work, but are willing and able to work

underemployment people in a job that doesn’t require the qualification or skills that the individual has

voluntary work working full-time or part-time without pay

(Courtesy: AET (June 1998) Employment Issues Facing Young Refugees in Haringey, P.4)

refugee community organisations

refugee organisations that are run and managed by people from a given nationality or ethnic group and usually serve members of that community

refugee agencies agencies that cater for refugees from all ethnic groups. For example, Refugee Council, RETAS, RAGU

Executive Summary

The Pan London Refugee Training and Employment Network commissioned the writers of this report to carry out research on ‘Refugees Progression Routes to Employment’. Recent studies indi-cate that 75-80 per cent of refugees are unemployed or underemployed. The major employment barriers are inter alia: lack of language skills, information and childcare facilities; cultural factors; deprivation and social exclusion; employers’ negative stereotyping of refugees; non-recognition of overseas qualifications; racism and prejudice.

The aim of this research is to look at the common pathways that refugees follow to seek suitable employment, how their choices have changed through time and the implications of these for the provision of training and career advice services.

Findings of the Study

1. The routes to employment taken by refugees vary according to factors such as age, level of qualification and type of profession. Younger refugees follow shorter routes and face fewer employment barriers than others do. However, problems with language proficiency and lack of employment opportunities stand in the way of young refugees who are trying to access apprenticeships and New Deal routes followed by other young people.

2. Many refugees who are qualified in regulated professions tend to follow alternative routes of conversion in related areas because of the prohibitive cost and time involved in re-qualifica-tion. However, as there are no standardised and readily available bridge courses to facilitate such conversion, most such conversion routes lead to long periods of training and often underemployment.

3. Qualified professionals with managerial and administrative backgrounds are the most disad-vantaged group in terms of routes to employment. They follow longer routes of postgraduate education, volunteering and so on, yet most are unable to find suitable employment.

4. Unqualified adults with some manual skills also have relatively short routes and fewer barri-ers to employment than othbarri-ers. The main barribarri-ers for this group are language skills and childcare.

5. Currently, training provision with refugee agencies is focused on certain areas such as lan-guage skills, care and hairdressing, office skills such as administration, IT and accountancy. Clearly, this is a reflection of the growing employment demand in the service sector. Such courses are vital routes to employment especially for those with managerial, administrative, finance and health backgrounds.

6. No customised courses are currently available with refugee agencies in retail or catering, nor for skilled crafts such as basic engineering, electronics, car maintenance, plumbing, carpen-try, bricklaying and textiles.

1. Introduction

Refugees1are often considered a burden rather than an economic boon to the host society in which

they live. However, refugees are not merely consumers who live off the resources of the host com-munity but are positive economic assets for the country of asylum. They can give much if given the opportunity to add to the economic prosperity as well as to the social and cultural life of the host country. Sadly, their contribution and resourcefulness is hardly recognised by the larger society. The knowledge, skills, and varied experiences which refugees bring with them are largely invisible to the public. Refugees’ limited access to mainstream employment is concrete evidence of their marginalization.

A Home Office study2 of refugees in the United Kingdom confirms that high levels of talent and

expertise are being wasted in Britain. The research concludes:

The majority of asylum seekers come with substantial work and educational qualifications, the bulk of which are under-utilised, to their chagrin and the country’s general loss. (Quoted in “Credit to the Nation”, Refugee Council, 1997)

The waste of refugees’ untapped resources needs to be redressed. Refugee community organisations (RCOs), refugee agencies and refugees themselves have taken several important steps to secure suitable employment for refugees. However, not enough has been done in terms of providing ad-equate and relevant training, careers advice and employment services. Most importantly, more lob-bying needs to be done to convince employers and policy makers that refugees have tremendous potential and a lot to offer to the U.K.

By its very nature, the refugee situation is highly volatile. Refugees are subject to traumatic and disorientating experiences of crisis in their home countries, which have forced them to flee leaving everything behind including family and friends. In the country of asylum, refugees face political and legal constraints, financial hardship and psycho-social difficulties, and problems due to cultural dif-ferences between the countries of origin and that of asylum. Lack of suitable employment is only one aspect of the refugee dilemma.

The problem of definition, categorisation and quantification of refugees remains one of the funda-mental impediments of refugee research. There is great difficulty in data collection and analysis of information that arises from the volatile situation of refugees. Hence the estimation of refugee popu-lation remains inexact, mainly due to lack of a comprehensive description and lack of consistency in the definitions of the term ‘refugee’ and classification of refugees. This problem is exacerbated by the continuous inflow and return of refugees. The most recent and accurate estimate of refuge num-bers in London is 240,000 to 280,000 from the report ‘Refugee Health in London’ by Health of Londoners Project 1999.This figure is based on 85 per cent of refugees in the U.K. living in London.

1 As a matter of convenience the term ‘Refugee’ is used to denote both refugees and asylum seekers

with permission to work.

The Refugee Council estimates 260,000 refugees and asylum seekers. (With the rising numbers of asylum applications over recent years and the effect of dispersal of many new arrivals outside Lon-don, the numbers of refugees within London is no longer such an accurate figure for the whole of the U.K. July 2000).

In the UN Refugee Convention of 1951, Article 1 Paragraph (2), the term Refugee is defined as any person:

Who owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted of reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or owing to such fear is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country, or who not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence, is unable or owing to such fear is unwilling to return to it. (UN, 21 July 1951)

The legal definition of refugees is a limited one and it has become increasingly difficult to show clearly ‘genuine’ refugees as distinct to ‘migrants’ as reasons for migration often become entwined. On one hand, people come to the ‘West’ either illegally or by claiming asylum. Then there is a growing trend for developed countries to seek skilled labour from developing countries such as Ger-many’s recruitment of skilled computer technicians from India. The movement of migrants unlike refugees is motivated by economic push or pull factors.

Although the movement of migrants may not be absolutely voluntary they, unlike refugees, are more likely to be able to choose their destinations and can go home without any fear of being persecuted. Refugees are forced to flee their homes due to factors beyond their control. They leave their coun-tries of origin in search of protection. In such precarious situations, many go from high status to lower status jobs. There are many refugees who have been medical doctors, lawyers, university pro-fessors, and even government ministers in their country of origin and ended up in menial jobs or with no job at all due to exile in a new society and the arduous process of re-qualification. They find that they have lost their economic and social status.

Migrants, on the other hand, generally leave their home countries for economic reasons i.e., to better themselves. They may have pre-planned arrangements to satisfy immigration requirements. They leave with expectations that they will have to find their own routes to economic prosperity. In time, as they settle their families often follow. This can also occur with refugees. The first generation of Afro-Caribbean and Asian migrants who migrated to the U.K. in the 50s and 60s after the Second World War are a good example of peoples invited to fill a labour shortage. Yet today, immigrants provide even greater benefits to Western economies. In 1999, 16 million legal immigrants in Europe earned more than $400 billion. The number of self-employed immigrants in the E.U. has increased by close to 20 per cent over the past seven years. In Italy, immigrants make up one third of labour in industrial and service sectors, even though they only comprise 2 per cent of the total population. In the U.K., the Chinese have a higher proportion of people working in the professions than non-Chinese and Indians earn more than the average family income of the rest of the population (Time magazine, July 2000). What this shows is that if given appropriate support, refugees can make a significant contribution to the economic life of the U.K.

2. Background

The writers of this report have been commissioned by the Pan London Refugee Training & ment Network (PLRTEN) to carry out research on ‘Refugees and Progression Routes to Employ-ment’ in the context that refugees suffer a high level of unemployment in the United Kingdom.

Overall, it can be said that there is little or no research done with direct reference to refugees’ pathways to employment. This study is by no means comprehensive. It is intended to contribute its part to the existing literature on refugee employment in the light of growing difficulties and the efforts made by various refugee organisations and refugees themselves.

PLRTEN is a partnership that involves different organisations from the public, private and voluntary sectors such as training providers, community organisations, employers and Training Enterprise Coun-cils. It was set up in November 1998 to improve training and employment services provided for refugees through sharing knowledge and information as well as capacity building of both member and non-member agencies by providing training and resources.

3. Aims and Objectives

The aim of this research is to discern the common pathways that refugees follow to seek suitable employment, how their choices and the influences on these choices have changed through time and the implications of these for provision of training and career advice services. The main objectives are:

- to explore the level of refugee employment and the main barriers faced.

- to examine the effects of proper training and professional advice or lack of it on prospects of refugee employment.

- to look at individual refugees, whether successful or not, and examine the pathways they have taken to find suitable employment and draw some learning experiences.

4. Methodology

This study is based mainly on face-to-face interviews with officials from refugee agencies and refu-gee community organisations and the findings of a questionnaire distributed to refurefu-gees. A cursory review of secondary resources of existing studies on refugee matters has been made.

Case studies of selected refugees and organisations and critical observation by the writers of this report have been employed to complement the aforementioned methods.

4.1 Interview

An interview was conducted with selected agency co-ordinators and careers advisers involved in guidance and training provision. A total of 30 organisations were interviewed, of which 12 were refugee community organisations, 13 refugee agencies and five non-refugee agencies. Most refugee agencies delivering training and/or guidance were contacted along with a selection of community organisations serving peoples from different ethnic backgrounds. (See Appendix I).

4.2 Questionnaire

A questionnaire for qualified refugees was another method used in data collection. The question-naire survey comprising open and closed questions was sent to 200 refugees who have been in the U.K. for over three years. Out of these, 30 refugees from 16 countries completed and returned the questionnaire. Ten other respondents’ replies were not used as they had been in the U.K. for less than two years and an incomplete view of these refugees’ progression routes could be gathered. The number of replies represented 60 per cent of the intended target group of 50 refugees from various countries (see Appendix IV for the summary of pathways of respondents and Appendix III for a sample questionnaire used in this research).

As the questionnaire was prepared in English, the participation of refugees with low levels of Eng-lish is obviously limited. There was neither the time nor the resources to assign interpreters or to translate the questionnaire into the refugees’ respective languages. This is a drawback of the study. Another limitation of the questionnaire is that the survey covers only those who have made use of the services of RCOs and refugee agencies. The reason is that we accessed the refugees in question through these organisations.

4.3 Review of prior research

Secondary resources such as previous studies on the subject, handbooks and annual reports of refu-gee agencies and RCOs and other related documents have been used for this study. A comparison has been made between the findings of the current study and various research outcomes on the subject.

4.4. Case studies

5. Review of literature

Literature with direct reference to refugees’ routes to employment is scant. Most previous studies on refugee unemployment have focused on the scale and nature of the problem. Some studies estimate 75 to 80 per cent of refugees are either unemployed or underemployed3 (Ahipeaud, 1998).

Accord-ing to an Africa Educational Trust report, the level of unemployment ranges between 75 and 90 per cent (AET, 1998b). Another more recent study suggests that the refugee unemployment rate is about 51 per cent (Barer, 1999). The latter figure is likely to be explained not only by the exclusion of those who are underemployed, but also by the inclusion in the survey of a higher proportion of those granted a positive immigration status, (i.e., refugees and those with exceptional leave to remain). In any case, this figure is staggeringly high compared to the national average of 5 per cent and the ethnic minorities’ average of 24 per cent. It has also been reported that refugee employment is highly concentrated in certain jobs such as catering, minicab driving, factory work, building site work, security, cleaning, petrol station jobs and supermarket jobs and to some degree in voluntary organi-sations and local authorities. (AET, 1998; mbA, 1999).

The nature of the refugee unemployment problem has been described as one characterised by multi-faceted barriers, which prevent refugees from participating in the workforce4. Since routes to

em-ployment are essentially the ways around these barriers, it would be instructive to start by examining these barriers. This will be followed by a brief review of two transition models one of which will be used in analysing some of our data.

5.1 The nature of refugee unemployment

Refugee employment barriers can be classified into two categories,internal and external. By internal, we mean barriers which naturally result from being a refugee, or for which refugees themselves are responsible. For example, for most refugees English is a second language. This problem has been highlighted in almost all previous research (See for example, AET, 1998; mbA, 1999).

The second major internal barrier is culture. As many refugees come from countries where the share of the corporate private sector is limited, they are not accustomed to the competitive job search culture which characterises western economies. The idea of selling one-self is unfamiliar to many people who might have been taught that modesty and deference are virtues which pay in life.5

Job search, though, is only one aspect of the role of culture in affecting refugee employment. In contrast to the traditional sectors such as manufacturing, construction and agriculture, which de-mand craft skills of ‘doing’ a job, the present service-dominated6 western economies require a

‘fit-ting in’ skill. Such a skill is often best acquired through years of acculturation rather than by short-term training. Such acculturation is often the least attainable trait for refugees, most of whom arrive as adults.

3 Underemployment in this context means being employed in an occupation which requires less skill and competence

than one is trained for. It can also mean working for lesser hours and lesser income than one is willing and able to work.

4 Work force in this context implies those who are in employment whereas labour force encompasses all those who

are in labour market – employed and unemployed but actively seeking work.

5 For a comparative study of job search culture in selected countries, please see Marshall, 1989.

6 The employment share of the service, manufacturing and agricultural sector in U.K. is about 75 per cent, 20 per

Refugees who arrived during and before World War II when manufacturing, mining, and building were the leading sectors , could not have encountered the barriers refugees of this generation face. In those days, there were also less entry barriers for small business refugee entrepreneurs as the number of those engaged in crafts such as tailoring, shoe making, furniture, and petty trade shows (Refugee Council, 1997).

Another barrier that arises out of being a refugee is a lack of appropriate skills. This is not to say that refugees are inherently unskilled. In fact, as confirmed by previous studies and our own interviews, refugees have a higher level of formal educational qualification (per population) than other groups. For example, according to the Home Office research report of 1995, 35 per cent of those who were surveyed had university education in their country of origin (sited in Barer, 1999). In our limited survey, 45 per cent of respondents had at least a degree qualification when they arrived in U.K.

However, whether such qualifications per se can become a skill is another question. As one study suggests, such high levels of qualifications show that refugees have got a good knowledge-based skill. However, such skill must be complemented by other generic and specialist skills such as tech-nological, interpersonal, teamwork and communication skills to be competitive in the labour market (RTEC, 1993). These generic and specialist skills are acquired more through practice than formal training. The fact that refugees, because of their status, tend to remain outside the workforce not only implies that they cannot keep pace with the changing skill demand of the economy, but also that they could lose whatever knowledge based skill they have. Therefore refugees are often caught in a vicious circle of lack of experience, lack of skill, and a lack of employment.

One final factor that needs mentioning in this category could be termed ‘the psychology of being a refugee’. Refugees may have experienced loss, separation and human rights abuses. Most have also lost social status and a sense of service to their community. Unlike their migrant counterparts who are pulled by opportunities, refugees are pushed by circumstances. All these can affect refugees’ confidence and motivation. One research report also suggests that refugees’ attitudes to a country of asylum and their aspiration for eventual return to their home country affect their participation in the labour market (Bloch, 1999).

Generally speaking, these internal barriers can be tackled through training and orientation. Refugees’ willingness, motivation and ability to learn and adapt to their new environment are also crucial in coping with these barriers.

The second category of barriers is external to refugees; i.e., they are beyond the scope of refugees’ influence. Consequently, they can only be tackled through legislative and policy interventions. One such barrier is the problem of being legally recognised as a refugee. In refugee crises triggered by post cold war nationalism (such as the Balkans), the percentage of people recognised as refugees is very low7. Although people can get permission to work six months after applying for asylum8, the process

of waiting to be recognised as a refugee affects both the individual’s confidence and the employers’ perception.

7 For example, from January to June 2000, only 16 per cent of asylum applicants were granted refugee status while 19

per cent were given Exceptional Leave to Remain. The remaining 65 per cent were refused (see the August 2000 issue of Refugee Council’s iNexile Magazine).

8 This is with reference to U.K. In most other European countries, it can take years for refugees to get permission to

More importantly, lack of legal status could deprive the individual of education and training oppor-tunities, which are vital to be competitive in the labour market9. This is probably the single most

important factor, which compels asylum seekers - most of them qualified - to take informal and casual employment.

The second major external barrier is explicit and tacit restrictions in different economic sectors. For example, because of nationality requirements, refugees cannot access civil service and defence jobs. However the barriers are more cultural in entering financial and business service jobs in banks, building societies, insurance companies and investment banks. This is partly confirmed by an evalu-ation report of the Africa Educevalu-ational Trust on the effectiveness of its grant scheme. This report found that those refugees who did training in business and computer studies – skills for which there is increasing demand in the mainstream labour market – had less employment success than those who did social work and healthcare training (AET, 2000).10 Moreover, professional services such as

accountancy, law and medicine are protected by the licensing and registration requirements, which are often long and costly processes; a subject we will return to in the next section.

Lack of accessible information is another major external barrier (see for example, Barer, 1999). Systematic tailor-made information and advice services for refugees are very limited and tend to be London-based. Many individuals may not be even aware of the availability of these services. This is evident from the fact that the number of individuals who make use of these services as compared to the yearly figure of asylum applications is extremely low. In our survey, we found that most respond-ents use friends and community organisations as a source of information and advice. This raises the question whether community organisations have the capacity to offer the quality of information and advice required about the labour market.

The fourth external factor is of course discrimination and racism. This has been highlighted in almost all previous researches as well as our own survey. However, unlike migrant and minority groups who place the cause of their predicament squarely at the door of racism, the role of this factor on refugee employment needs to be examined in the context of the multi-faceted layers discussed above.

In conclusion, refugee unemployment problems cannot be explained in the conventional concepts of being voluntary, frictional or even structural.11 These concepts mainly apply to those who are

al-ready in the workforce while refugees have faced barriers that have severely limited their participa-tion in the labour market. Some of these barriers are internal to refugees and consequently can be tackled through orientation, training and education. However, other barriers relate to external condi-tions about which refugees are virtually powerless to do anything and which need legislative and policy intervention.

9 For example asylum seekers are not eligible for statutory loans and grants for higher education. They might even be

required to pay the overseas rate fee if they want to finance their study. Also. they are not currently eligible for government funded vocational training.

10 This problem has also been highlighted in RTEC, 1993. These findings corroborate with the dual labour market

theory which argues that labour market is segmented and therefore, individuals from different socio-economic background do not have equal chance of accessing employment in all sectors, despite having comparable level of

qualification (see for example Atkinson, et al, 1986)

11 Voluntary unemployment arises when people are unwilling to take up employment at the going wage rate whereas

In the following sections of this report, we shall examine how these barriers are manifested in routes and pathways refugees take to find suitable employment.

5.2 Transition Models

Tony Marshall in his book ‘Career Guidance with Refugees’ (1992), distinguishes the following stages in refugees career pattern:

Disorientation is a time when one learns to come to terms with a new environment and is over-whelmed by basic survival needs such as food, housing and asylum. At this stage people might need more counselling, orientation and confidence building support. Optimism is a stage when especially qualified refugees might start seeking employment commensurate to their qualification or look for postgraduate education. Disillusionment and depression arises when optimism is frustrated by the number of job applications turned down and lack of funds. A ‘Trigger’, on the other hand, is caused by a piece of information about an opportunity either from friends, community groups, tutors or advisors which might be followed by opportunities such as training, bridge course, funding etc. This could eventually lead to suitable employment or lack of it as in ‘a’ (suitable employment),‘b’ (under employment), and ‘c’ (unemployment) on Fig 1.

Instructive as this model is, its usefulness for analyses of our data is limited for two reasons. Firstly, it primarily focuses on the psychological cycle that refugees experience. Secondly, because of the timing of the writing of the book, it fails to capture changes in the diversity of the refugee popula-tion as well as changes in immigrapopula-tion and asylum laws.

Another transition model developed by the Employment Policy Advisor at the Refugee Council identifies four stages (Please see appendix V for the diagram).

1. Reception/Verification

2. Orientation (e.g., information about U.K. education, training and employment system, ESOL)

3. Pathways to work (e.g. careers advice, tailor-made orientation, confidence building, key skills, work based learning for adults, re-qualification and conversion courses)

4. In Job Support (e.g. job search, job preparation, specialist recruitment)

Such a sketch of stages in service provision is useful and will be adopted in our study. However, as we shall see in this report, it is difficult to discern a common pathway for all refugees. Therefore, a service provision model should also acknowledge diversity between various groups of refugees.

Morale

Time

1 orientation

(a)

(b)

6 Direction

(c)

2 Optimism

3 Disillusionment

4 Trigger

[image:17.595.104.538.173.355.2]5 Opportunity

Figure 1: Tony Marshall’s Transition Model

under employment

6. Analysis of refugees’ responses to questionnaires

In this section we will try to discern the pathways refugees have taken in seeking and finding suitable employment based on analysis of questionnaires. We start by presenting a characteristic profile of respondents and their various stages of their destinations after arrival in the U.K. This will be fol-lowed by analyses of their pathways. The section ends by attempting a model pathway. Case studies of some individual refugees have been included in the appendices.

6.1 Characteristic profile of respondents upon arrival

Ethnicity, age and gender

The 30 respondents are from diverse ethnic backgrounds: Middle East, Africa, Europe, Asia, and South America (please see appendix IV for the country of origin of respondents). Nineteen of these are men while eleven of them are women. Sixty per cent are between the ages of 35 and 45 while twenty per cent are below the age of 35.

Educational background upon arrival

Forty-seven per cent of respondents had a graduate degree as their highest qualification when they arrived in U.K. while twenty per cent had a postgraduate degree. Another 20 per cent had a second-ary school or below level of education when they arrived whereas 13 per cent had post-secondsecond-ary school training.

Employment background upon arrival

Twenty-four respondents had paid employment experience when they arrived out of which sixteen worked in the public sector, some of whom also worked in a self-employed professional capacity as family doctors, dentists and lawyers. Only four people had worked for private companies and three for non-governmental organisations. One respondent was a self-employed businessman.

In summary, most of our respondents are middle-aged men who had a high level of educational qualification and employment experience in the public sector in their country of origin.

Table 1: Employment sectors of those who had employment experience in their country of origin12

12 Please note that the percentages are computed out of 24 respondents who had experience. Please also note that the

figures do not sum up 24 & 100 per cent because people have worked in more than one sector. Some respondents have worked in both public and private sectors. For example, some medical doctors run private clinics while at the same time working in hospitals.

r o t c e

S Number Percentage

c il b u

P 16 67

s e it ir a h c / s O G

N 3 12

s e i n a p m o c e t a v ir

P 4 17

l a n o i s s e f o r p d e y o l p m e -fl e

S 6 25

s s e n i s u b d e y o l p m e -fl e

6.2 Destinations after arrival

Employment

Sixty-three per cent of our respondents are currently unemployed. The average period of unemploy-ment for all our respondents is about five years. Of those who are in employunemploy-ment, two are under-employed working in security and similar areas though they have graduate and post-graduate qualifi-cations from the U.K. Forty-five per cent of those who are in employment found their present job within the last year.

Thirteen of our respondents (43 per cent) had some sort of paid employment experience between their arrival and their present circumstance (whether employed or unemployed). However, seven of these had their paid employment in retail, cleaning, catering and security jobs. Two people have worked as a mail sorter and dressmaker. Only four people have worked in what could be called a semi-professional capacity such as Assistant Librarian, Assistant Newspaper Editor/Graphic De-signer, Refugee Project/Development Worker, and Temporary Event Organiser/Project Evaluator.

Personal contact is the most common means of applying for jobs for those who have employment experience in the U.K. The use of newspapers ranks second in the list. Fewer people have used voluntary work or mainstream employment services such as the job centre to find a job.

Education and training

Six of our respondents did their graduate degree in the U.K. Five of these (83 per cent) are currently in employment. The common feature of these respondents is that they arrived when relatively young and they did not have paid employment in their country of origin. Five respondents have done postgraduate degrees since they arrived in subjects such as Chemistry, Environmental Science, Man-power Studies and International Politics (see R7, R8, R10, R11 and R12 in Appendix IV).

However, in sharp contrast to those who did their graduate studies in the U.K., four of these (80 per cent) are unemployed and even the one who is in employment is one of the under-employed re-spondents.

Other short term training courses taken by respondents were Information Technology, ESOL, Elec-tronics, Computer Networking, Insurance, Technician Level Accountancy, Administration, Personal Development, Health and Social Care, Advice, Job Search, APEL, Interpretation and Nursing. The most common of these were IT and ESOL.

13 Of course some refugees use more than one medium to find work successfully.

Table 2: Medium used to find a job13

b o j a d n if o t d e s u m u i d e

M Number of respondents Percentage

e r t n e C b o

J 2 11

r e p a p s w e

N 4 22

y ti n u m m o c & t c a t n o c l a n o s r e

P 8 45

k r o w y r a t n u l o

V 2 11

r o s i v d a r e e r a c y c n e g a e e g u f e

R 2 11

l a t o

Career Guidance

In response to the question asking whether they have received career guidance from listed sources, the majority of respondents (about 60 per cent) said that they have been advised by friends and community organisations. Five respondents said they had never sought any career advice from any-where. It is interesting to note that those respondents who have attended guidance training courses such as RETAS’s Job Search and RAGU’s APEL14 had more chances of finding temporary or full

time employment than others (see for example R22, R23, R25 in Appendix IV). This shows that receiving a customised guidance course is more effective than a one-off advice service.

The questionnaire also showed that those who use job centres, colleges, and local council advice services generally tend to be the ones who have stayed in the U.K. for a longer period of time. Other agencies used by the respondents for career guidance were the Refugee Council’s Training and Em-ployment Section and the Africa Educational Trust (See table 3).

14 RETAS : Refugee Education Training and Advisory Services

RAGU: Refugee Assessment and Guidance Unit APEL: Accreditation of Prior Experiential Learning

15 The percentage refers to the numbers out of the 30 surveyed that have used a particular approach.

Considering the monthly and yearly number of asylum applications, it seems that the majority of asylum seekers and refugees do not make use of refugee career guidance services. An independent survey is needed to establish a more accurate picture of this issue.

Placements and voluntary work

Placements in the form of clinical attachments are very common among regulated professions such as Medicine and Dentistry for those who are aspiring to re-qualify. Some people find placement opportunities as a part of a work-based learning program. Other professionals have been assisted by guidance agencies such as RETAS and RAGU to find a placement without necessarily doing training.

Eight of our respondents (27 per cent) have done voluntary work. The common feature of this group is that they tend to be qualified and middle-aged (See R6, R8, R10, R11, R12, R20, R21, R23 in appendix IV). It is ironic that only one of these is currently in paid employment.

Table 3: Career guidance centres used by respondents15

y c n e g

A Number Percentage

e r t n e C b o

J 3 10

) S E T ( li c n u o C e e g u f e

R 3 10

U G A

R 5 17

S A T E

R 5 17

t s u r T l a n o it a c u d E a c ir f

A 1 3

s e g e ll o C / s e it i s r e v i n

U 6 20

s e c i v r e s r e e r a c li c n u o

C 4 13

n o it a s i n a g r o y ti n u m m o

C 8 27

s d n e ir

F 10 33

e c i v d a r e e r a c d a h r e v e

If we were to make a judgement from this evidence we could say that, unlike the findings of some previous studies,16 ‘those who volunteer do not necessarily have a better chance of securing suitable employment

than those who don’t.’ However, as we will see shortly, those who tend to volunteer as a means to employment are those who already have multiple disadvantages such as age and over-qualification. In any case, more independent research would be needed to establish the role of volunteering as a route to employment.17

To summarise, our data corroborates the findings of previous research that most refugees are unem-ployed or underemunem-ployed. Informal personal contact is the most common means of getting informa-tion and advice as well as for applying for jobs, except for those who have stayed in the U.K. for a longer period of time and who tend to use mainstream career and employment services. It also appears that the higher the level of qualification and work experience in one’s country of origin, the more difficult it is to secure suitable employment.

6.3. Employment barriers as seen by refugees

16 One such study has been cited in section 7 of this report.

17 A research project on establishing a link between volunteering and employment was conducted by Susan

Stopforth 2000.

18

Respondents were asked to list up to three main barriers to employment for themselves.

The questionnaire respondents saw English language skills and the lack of U.K work experience as the two most important barriers. These were followed by other factors such as the lack of recognition of overseas qualification and lack of orientation to the U.K labour market and job culture. (See Table 4). This would seem to substantiate the findings of the research sponsored by the Peabody Trust (Barer, 1999).

Table 4: Employment barriers as seen by refugees18

r e i r r a B f o e p y

T Number of respondents

n o it a c if il a u q s a e s r e v o f o y ti d il a v n I 9 ll i k s e g a u g n a l h s il g n E f o k c a

L 16

e c n e ir e p x e k r o w . K . U f o k c a

L 11

[image:21.595.72.431.314.589.2]6.4 Issues within employment

For the question asking what issues refugees who are already in employment face, most respondents gave comments such as the following:

“ Fellow workers create problems; they want to become managers and tell you what to do.”

“ Although I am hard working and competent there is no promotion because there is hidden discrimination.”

“ Managers have a condescending attitude.”

“ There are cultural differences.”

It should also be noted that there are some respondents who are satisfied in their current job and did not raise any significant work place issues. However, since the percentage of our respondents who are currently in employment is very low, no conclusive statement can be made about issues that refugees in employment face. The subject requires independent research of its own.

6.5 Common pathways to employment

The survey reveals that some common routes to employment have emerged. This provides a basis on which to decide whether more specialised support is required. This includes the paths taken by those in work and those still seeking work. The pathways of each individual respondent have been pre-sented in Appendix IV. From this, we have discerned four common patterns:

i. Those who arrive at a young age and did not have paid employment experience in their country of origin;

ii. Professionals who need to be licensed and registered to practice their professions;

iii. Qualified individuals with managerial, administrative and other professional backgrounds; iv. Unqualified adults, i.e., those who have little formal education.

i. Those who arrive young

This is a typical route followed by people who arrive up to the age of 21 with or without college education. Their first problem is, of course, English language. They might need to do GCSEs19 and

A levels20 to go to higher education. The older ones such as R25 (questionnaire respondent - see

Appendix IV) might take alternative routes such as GNVQs21 and Access courses. Over all, this

group seems to have a better chance of securing private and public sector employment than others (see R3, R13, R15, R16 and R24 in appendix IV).

19 General Certificate of Secondary Education

20 Advanced level

Young people up to the age of 18 have free access to schools as well as some further education courses. However, the practicality of finding places in schools or colleges at a time when this is needed is complex and can often mean refugees having no education for a while. Lack of employ-ment opportunities and proficiency in English also limit the chance of young refugees accessing opportunities such as Modern Apprenticeships, National Traineeships and New Deal schemes.

ii. Those in regulated professions

The main barrier for this category is re-qualification requirements. This is especially the case for doctors and lawyers. Doctors need to pass at least three examinations (IELTS, PLAB22 stage 1 & 2) to

qualify for limited registration with the General Medical Council. As well as the cost of preparation fees, the examination costs are high and some hospitals ask for a weekly tuition of up to £85 for clinical attachments. The pass rate for the PLAB examination is estimated to be only 35 per cent. As one informant told us,23 there are many people who remain unemployed even after passing all stages.

The same is true with lawyers, especially those from non-EU and non-common law jurisdiction countries.24

None of our professional respondents have gone through all the processes and found suitable em-ployment. Some have recently embarked on the process (see R1, R2, R19 in appendix IV). Others have converted to related semi-professional areas. For example, R12 has converted from a law back-ground to advocacy work with communities and a Citizens Advice Bureau. A course on advocacy has helped him to achieve this. R20, who was a medical doctor, has converted to a health advice occupation after doing various courses on advice issues to do with money, health and homelessness advice. R29, was also a medical doctor, converted to senior staff nursing after taking a nursing adaptation course. Some teachers, apparently unable to meet the qualified teachers status require-ment which, among other things, requires advanced communication skills, have taken related con-version courses that helped them find employment in interpretation, translation, advice and commu-nity work. Although these new conversion careers are not equivalent to previous occupations, they have helped a move towards more suitable employment.

22 IELTS stands for International English Language Test Services and PLAB stands for Professional and Linguistic

Assessment Board

23 Interview with Refugees Into Job Co-ordinator

24 See Hernan Rosenkranz, The Refugee Professionals’ Guide on Assessment and Recognition of Overseas

Qualifications.

Figure 2: Young refugees’ route to employment

Basic ESOL

Arrival GNVQ or A level Access to HE course

Higher Education Temporary

jobs

Fulltime employment Completed

primary, secondary school or college course in home country

Therefore, using Tony Marshall’s transition model, the likelihood of refugees in regulated profes-sions finding the same job is low. However, there is a reasonable chance of them finding a related less-qualified job, which would mean underemployment (b).

iii. Qualified individuals with managerial and administrative skills

This group has got the least clear path of all. As there is no established re-qualification route, individuals in this category are their own pathfinders.

As Tony Marshall suggests, qualified individuals with management and administrative skills start with optimism by doing a Masters or a Doctorate level of education and by applying for related jobs. When this fails, as very often it does, they seek careers advice, do work based learning courses and voluntary work. When entry occurs into the labour market it is likely to be at a much lower level than anticipated as expectations have decreased. They are very likely to be in the majority of qualified refugees who are unemployed (see R6, R7, R8, R9, R11, R18, R21, R25 in appendix IV).

[image:24.595.65.516.159.280.2]Figure 3: Routes to employment of refugees in regulated professions

Figure 4: Routes to employment of qualified refugees with managerial and administrative experience.

Arrival - Benefit - Housing - Asylum

Low paid casual

jobs

Unsuccessful job applications

Freelance, sessional and temporary jobs - WBLA - Placement - Volunteering Orientation,

ESOL, IT Postgraduate

education Arrival

- Benefit - Housing - Asylum

- Guidance - Intermediate ESOL - Professional English

- WBLA - Placement, Volunteering

Employment in related areas (e.g., advocacy, community) Suitable Employment

Re-qualification route

iv. Common pathways for non-qualified adults25

As we do not have questionnaire respondents in this category, we rely on our discussion with informants and our own observations.

Most individuals in this category generally tend to have some manual and craft skills including cater-ing, dressmaking and hairdressing. Others could be unskilled. In either case, as one informant told us,26 they are willing and ready to take up jobs, albeit temporary, part-time or low paid. Because of

lack of formal education, language is the major barrier for this group - hence the need for different levels of ESOL training. As this group is composed mainly of women27, childcare is another barrier.

In short, this group is characterised by a willingness to take up jobs without fear of being underem-ployed on one hand, and language and childcare barriers on the other hand. This is reflected in the variety of routes they follow as in Fig.5.

25 This is to mean adults with little formal education

26 Interview with Integra Refugee Employment and Advice Centre

27 The fact that more refugee women than men are prepared to take low paid and part time jobs has also been

[image:25.595.86.506.123.444.2]highlighted in the recent Peabody Trust report (Barer, 1999). Figure 5: Routes to employment for unqualified refugees

Arrival - Benefit- Housing - Asylum

Inter-mediate

ESOL

Self employment (catering, hairdressing, minicab, etc)

Temporary or part-time work in clerical, sales, care, etc

Job search support

Basic skills training such as ESOL, IT, literacy, numeracy

P/T FE courses

WBLA courses

Employment in catering, retail etc, childcare

Figure 6: Model Pathway

Conclusion: “Model Pathway” based on previous models.

(Reception)

Community led service

(Gateway training) Refugee Agencies led service

(Integration) Mainstream services

Arrival

Counselling Housing, Benefit, Health (GP)

Basic ESOL & IT

Orientation and guidancecourse APEL Basic skills

ESOL & IT (continued)

Plan for Action

Re-qualification Conversion Postgraduate education

Higher Level ESOL

- Placement - Volunteering -Job search support (e.g., Job brokerage)

Apprenticeship Mentoring

GNVQ A level

Higher education Suitable

employment including self-employment

Intermediate ESOL

WBLA Information

Professional & Academic English

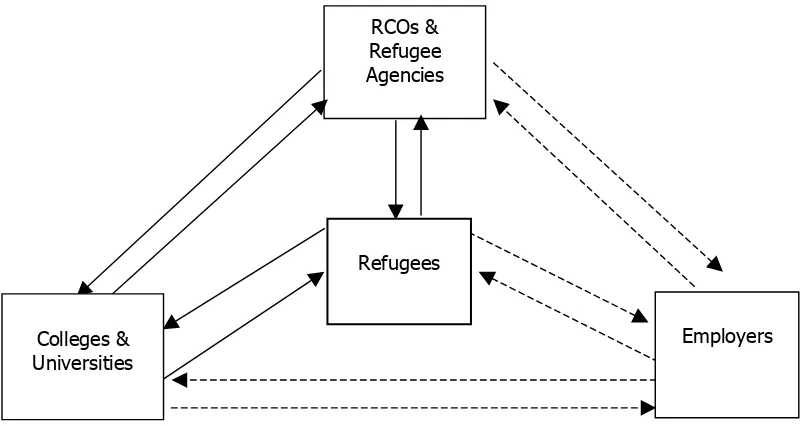

The essence of the model as compared to the two examined in the literature review section is three-fold. Firstly, an attempt to chart refugees’ pathways to employment should come within a ‘gateway’ type phase, which would include guidance, the chance to learn basic skills, awareness raising about opportunities and constraints in the labour market, assessment and self assessment.28 After, this,

individuals would be able to make informed choices about their career. It is important that that is provided as early as possible and preferably before leave to remain is granted.29 The guidance training

itself could last for three months, as in the case of APEL and should be followed by integration support from refugee agencies and mainstream service providers. At present, only comparatively few asylum seekers access APEL and guidance. This is due to them having to deal with other issues as well as being able to find their way through the system to these providers. Where refugees are still not eligible for having their studies funded by statutory grants or loans they would benefit from subsidised customised training, such as with ‘New Deal’ provision or a specialist job brokerage which has ‘Into Job’ support.

Secondly, the employment pathway model should acknowledge different routes followed by various groups such as the young, the professionals, those with managerial and administrative backgrounds and the unqualified but skilled adults. The fact that they follow different paths shows that they face different types of barriers. This calls for different strategic interventions.

Thirdly, at each stage of transition, the degree of roles played by various agencies should be spelt out. For example, refugee community organisations (RCOs) are best placed to play a leading role at the reception stage. Non-community refugee agencies are better equipped to deal with the stage of gateway guidance and training, though this should not totally exclude RCOs. Gradually, as people are integrated into a wider society, it could be easier to access the mainstream services including ones offered by and for ethnic minorities. However, there should be flexibility for refugees still to access guidance and courses even when they are well into the ‘integration’ phase as they are likely to require more specialist services then. There is also room for refugees and their advisers to make greater use of information technology as a resource to access the relevant services.

28 Such assessment and self assessment is currently being carried out through a three-month long APEL programme

of RAGU and a one week Plan for Action Workshop of TES. Through APEL programme professional refugees are enabled to build a portfolio of their previous achievements whether through education or experience. This would enable guidance provision on appropriate additional education or training needed. Plan for Action on the other hand involves intensive orientation about the trends in the labour market and key skills assessment such as literacy (writing, reading and speaking) numeracy, IT, problem solving and team work. At the end of the workshop, clients have an idea of their training needs and with the help of an advisor, they can set a tentative workable goals and draft a specific action plans for achieving them. Currently, TES’s Plan for Action workshop is provided only for potential trainees.

29

7. Analysis of interviews / contact with organisations

Many refugee community organisations and refugee agencies put a great deal of emphasis on the employment and employability of refugees. However, this tends to come after basic and immediate needs such as immigration, housing, and welfare services being satisfactorily resolved. In order to assist their clients settling into an ‘unfamiliar’ society these organisations mainly deploy their scant resources to provide basic skills training by way of numeracy and literacy, ESOL and IT training, and supplementary education. Some also provide career advice with training. They assist refugees in their job search, work placement, voluntary work, assessment of prior learning and re-qualification schemes (for qualified refugees).

7.1 Employment barriers as seen by refugee community organisations and refugee agencies

The interview results more or less confirm the type and nature of employment barriers identified by the employment literature. The results of the respondents can be classified as follows:

For refugees

· Lack of language and communication skills: These can affect refugees in the job search process.

· Mental stress and trauma: As well as having to leave their homeland in difficult circum-stances refugees face increasing disorientation in the country of asylum as they face differing physical, social and cultural environments.

· Lack of information: Lack of knowledge on how the employment system operates. As one interviewee said: ‘Those who get jobs are those who know the grapevine’. `They do not fully understand the U.K. system of job-hunting, which is different from that of their countries of origin’ (Marshall, 1989).

· Cultural barriers: The culture of job seeking and work in the west involves mannerisms such as accent, body language and codes of dress which often for many are entirely different from that of their home countries.

· Long-term unemployment: Refugees often naively believe that they will find suitable employment easily. Subsequently, many are not prepared for the greater effort required, be-come discouraged and are not keen to write speculative applications directly to employers on their own initiative perhaps due to cultural constraints or fear of rejection.

By employers and funders

· Lack of adequate training: Agencies and RCOs believe this in part due to lack of suffi-cient resources. Funders often give very little emphasis to personal development, ESOL training or certain vocational training, such as practical trades, which have higher set up costs. They attach stringent financial conditions such as employment outcome targets before they earmark funds, which cannot be met by training providers.

· Racism and prejudice: In addition to issues mentioned in the literature review the media also plays a significant role in portraying negative images of refugees. As one of the inter-viewees pointed out, ‘the power of the media is overwhelming and to counter that is diffi-cult’.

· Negative stereotyping: Agencies also say that many employers are not willing to accept refugees as their potential employees because they perceive that refugees are unable to work the way they want them to work. Moreover, refugees are indirectly discriminated against when they are asked to show the Home Office document, which makes them eligible for work. Many employers do not understand which documents are needed. Also, since the 1996 Asylum & Immigration Act employers can be fined if they employ those without the correct papers. This in turn has affected employers’ willingness to recruit refugees, as many employ-ers are worried that they may be ‘illegal’ immigrants and do not make the effort to make proper enquiries about their documentation.

· Lack of recognition of overseas qualifications: This is a particular problem mainly en-countered by highly educated refugees in regulated professions. They not only have to pass arduous testing processes set by assessing bodies, but also have to shoulder the burden of very expensive test fees. There are no specialist services at affordable prices. For example, as from April 2001 the General Medical Council set fees for the PLAB test of £145 for part one and £430 for part two. In addition, there are fees for the IECTS exam and preparation, clini-cal attachment, etc. Consequently, these costs are a significant barrier for refugee mediclini-cal doctors who are likely to have no source of income.

· Lack of childcare facilities: Refugee women with children who are well qualified and eligi-ble to work stay at home to look after their children due to lack of childcare facilities. This also applies to some men with children whose partners are at work or do not live with them.

Key elements in progression to employment

The organisations (see Appendix 1) that were interviewed identified the following as being cru-cial in the progression to employment for refugees.

· Personal development: The need to identify past experiences, personal skills and abilities and the level of confidence of the refugees who seek employment is of paramount impor-tance. Confidence, commitment, determination, vigour, optimism, assertiveness and energy are some essential qualities. These coupled with their own resilience, industriousness, and diverse socio-cultural backgrounds can put some refugees at an advantageous position for employment in advice, international media and translation/interpreting work.

· Training: These usually include courses such as ESOL and IT, communication skills and job search, and employment preparation. Even more important are customised and market-able courses such as catering, childcare, dressmaking and hairdressing which are intimately linked with the needs of employers and are personally useful to refugees within their own communities.

· Careers advice and guidance: Careers advice and guidance provides information on op-tions and helps refugees decide on the most appropriate education, training and employment to take. It is useful at different stages of the progression route. This support also helps refu-gees to become focused on their job search efforts.

· Volunteering: Unlikesomeone on awork placement, a volunteer may not necessarily intend to move into permanent employment. According to a recent study, volunteering in refugee community organisations ranges from:

the governance and management functions carried out by trustees and management committee mem-bers to the direct service delivery which usually involves advice on a wide range of issues ( immigra-tion and asylum, housing, welfare rights, educaimmigra-tion and employment etc) as well as advocacy and interpretation to numerous agencies. (Gillett, and Gregg, 1999)

Although it is normally done out of sheer commitment to serve people from theirown or other communities, there are still many refugees who use voluntary work as a route to obtain-ing employment. For example, the above study demonstrates 81 per cent of those with pro-fessional jobs had done voluntary work.

· Mentoring: One to one support from more experienced professionals is another very effec-tive way of assisting refugees into employment. The mentors could be refugees themselves, thus having both an in-depth knowledge of the talents, needs and aspirations of their fellow refugees and the employers’ needs.

· Networking: Personal contacts both within their communities and outside have helped refu-gees find employment. There seems to be a common understanding among refugee commu-nity organisations and refugee agencies that through networking ‘you always know somebody who knows somebody’ who can assist in the progression route to employment. In reality this is usually limited to a narrow range of jobs within the refugee voluntary sector and small-scale private sector. Referrals to suitable training providers and workplaces have enabled many unemployed refugees to gain access to further training and/or employment. However, in the public sector and the wider voluntary sector equal opportunities policies only get the refugee to the ‘starting line’ of applying and perhaps to an interview. For most refugees ac-cess to the ‘grapevine’ of jobs in the corporate sector is particularly hard.

· Self-employment: Many refugees often opt for this when formal avenues are not available to them and because they want independence. Small businesses such as shops, restaurants, and textile work are among the most common businesses that refugees are involved with and often serve their own communities rather than the wider society.

7.2 Overview of existing training and careers advice services

7.2.1 Profile of clients receiving services from different organisations

The educational attainment of refugees who receive training and careers advice services vary from those with higher degrees and diplomas to those who can hardly read and write in English or even their own languages. The numbers of well-educated refugees is high in many refugee communities. In the Kurdish Cultural Centre, qualified refugees i.e., refugees with first and second degrees (mostly Iraqis) represent about 80 per cent of their clients.

Quite a few of the refugee agencies concentrate on working with professionals. At Praxis, statistics shows that out of 100 sample group 43 per cent had 1st degree, 12 per cent had an MA or MSc, and

7 per cent had a PhD both from U.K. and overseas. At the Migrant Training Centre, the majority have degrees and diplomas from their own countries: doctors, teachers, lawyers, and even former minis-ters. All of the Refugee Health Professionals Project’s clients have overseas qualifications and ad-equate work experience. At the University of North London RAGU project, 60 per cent of refugees have a first degree and above.

7.2.2 Advice services

The programmes of many refugee community organisations focus mainly on asylum seekers from the same cultural backgrounds who face issues related to immigration, housing, welfare/benefits, health, childcare and the education of school age children. As most of these issues are pressing and most of these groups are underfunded and understaffed, they often have to put clients on a waiting list.

Refugee community organisations also emphasise that the social and cultural needs of refugees are equally as important as education. Indeed, the fulfilment of these needs can strengthen the effective-ness of employment and education advice and subsequent referral to other agencies. In most com-munities, employment and education advice tends to be given informally according to the immediate needs of their clients, though usually they do not have the capacity to properly advise those with higher qualifications. Sometimes people will be referred to the more specialist agencies but if, as often happens, there are insufficient links, then the client will have to find their own way to the appropriate support.

Using advice skills gained in these areas, some RCOs have developed education and employment guidance services. These include the individual refugee training partnerships in central London, which have given their members direct access to careers advice services provided locally. Also, some of their members such as GHARWEG and African Council Immigration Service (ACCIS) offer services for clients from more than one country, a trend which funders seem increasingly keen to see.

The Refugee Council’s Training and Employment Section (TES) provides a major vocational and self-employment advice service to refugees, seeing over 2,500 individuals a year. RETAS, though tending to concentrate on professional refugees, is also a major provider of advice on training and employment. In 2000, it saw over 100 clients for job search and 30 each for business start up and NVQ level 3 in advice work. Meanwhile, the Refugee Employment Advice Service at Hounslow Law Centre deals with a cross section of enquiries, ranging from rights to study and work to ESOL to re-qualification and job seeking. Even here, 44 per cent of clients are from professional back-grounds.

In other agencies like Enterprise Careers Services and South Bank Careers the number of refugee clients does not exceed 5 per cent, as their mandate is to primarily offer services to non-refugees. They were initially set up to serve young people between the ages of 16 and 21, irrespective of ethnic and racial background or whether a person is a refugee or an asylum seeker. Quite a lot of young refugees will go to these services as they have been referred through the education system. In contrast to these agencies, there is no age limit for the services offered by refugee community organi-sations, though most of their clients are over the age of 25.

7.2.3 Training

Most refugee community organisations and refugee agencies run similar training programmes al-though the level and scale of the training may vary from one organisation to the other. The most common are basic skills training (literacy and numeracy); ESOL and IT levels I and II; job search skills such as writing application forms and CVs; conducting mock interviews, mentoring, offering work placements and referrals.