Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Asthma

Effects of Medical and Surgical Antireflux Therapy on Asthma Control

David J. Bowrey, FRCS(Engl), Jeffrey H. Peters, MD, and Tom R. DeMeester, MDFrom the Department of Surgery, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California

Objective

To critique the English-language reports describing the effects of medical and surgical antireflux therapy on respiratory symptoms and function in patients with asthma. Methods

The Medline computerized database (1959 –1999) was searched, and all publications relating to both asthma and gastroesophageal reflux disease were retrieved.

Results

Seven of nine trials of histamine-receptor antagonists showed a treatment-related improvement in asthma symptoms, with half of the patients benefiting. Only one study identified a ben-eficial effect on objective measures of pulmonary function. Three of six trials of proton pump inhibitors documented im-provement in asthma symptoms with treatment; benefit was

seen in 25% of patients. Half of the studies reported improve-ment in pulmonary function, but the effect occurred in fewer than 15% of patients. In the one study that used optimal anti-secretory therapy, asthma symptoms were improved in 67% of patients and pulmonary function was improved in 20%. Combined data from 5 pediatric and 14 adult studies of anti-reflux surgery indicated that almost 90% of children and 70% of adults had improvement in respiratory symptoms, with ap-proximately one third experiencing improvements in objective measures of pulmonary function.

Conclusions

Fundoplication has been consistently shown to ameliorate reflux-induced asthma; results are superior to the published results of antisecretory therapy. Optimal medical therapy may offer similar results, but large studies providing support for this assertion are lacking.

Population-based studies have reported that one third of Western populations have symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) at least once a month, with 4% to 7% of the population having daily symptoms.1,2 Analogous studies have reported a 10% to 15% prevalence of asthma in the community.3–12Given these observations, it would not be surprising if the two conditions coexisted in some pa-tients. Several reports have indicated that up to 50% of patients with asthma have either endoscopic evidence of esophagitis or increased esophageal acid exposure on 24-hour ambulatory pH monitoring.13–19This suggests that the frequency of dual pathology is higher than would be ex-pected by serendipity alone. In addition, antireflux therapy may reduce the severity of respiratory symptoms in patients with both asthma and GERD.

Despite the ubiquitous nature of both diseases and the documented association between asthma and GERD,

con-troversy remains regarding the value of antireflux therapy in asthma. This reflects the small number of reports, the pau-city of controlled studies, and the conflicting findings of many studies. With this in mind, the current study aimed to answer the following questions:

● Does medical therapy improve asthma control? ● If yes, what is the optimal medication and dosage? ● Does antireflux surgery improve asthma control? ● Is surgery superior to medical therapy?

To address these questions, a literature search of the Ovid Medline database was performed to identify all English-language publications (1959 –1998) relating to both asthma and GERD.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF REFLUX-INDUCED ASTHMA

Two mechanisms have been proposed as the pathogenesis of reflux-induced asthmatic symptoms. The first, the so-called “reflux” theory, maintains that respiratory symptoms are the result of the aspiration of gastric contents. The

Correspondence: Jeffrey H. Peters, MD, Dept. of Surgery, University of Southern California, HCC Suite 514, 1510 San Pablo St., Los Angeles, CA 90033-4612.

Accepted for publication September 14, 1999.

© 2000 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc.

second or “reflex” theory maintains that vagally mediated bronchoconstriction follows acidification of the lower esophagus.

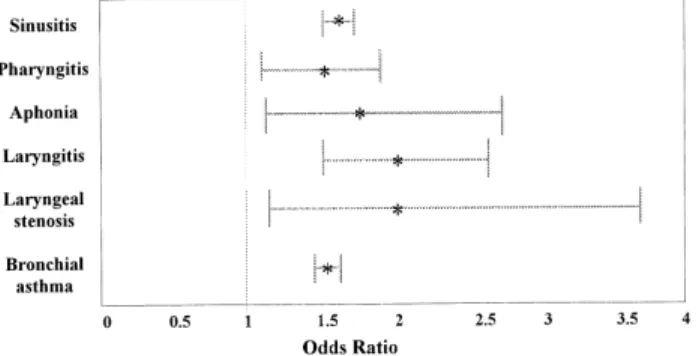

The evidence supporting a reflux mechanism is fivefold. First, clinical studies have documented a strong correlation between idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and hiatal hernia.20 Complicated GERD was shown to be highly associated with several pulmonary diseases, including asthma, in a recent Department of Veterans Affairs study (Fig. 1).21 Second,

pathologic acid exposure in the proximal esophagus is often identified in patients with respiratory symptoms and GERD (Fig. 2).16,19Third, scintigraphic studies have shown aspi-ration of ingested radioisotope in some patients with reflux and respiratory symptoms.22 Fourth, simultaneous tracheal and esophageal pH monitoring in patients with GERD has documented tracheal acidification in concert with esopha-geal acidification.23,24 Finally, animal studies have shown that tracheal instillation of hydrochloric acid profoundly increases airways resistance.25 A reflex mechanism is pri-marily supported by the fact that bronchoconstriction occurs after the infusion of acid into the lower esophagus.26 –29 This can be explained by the common embryologic origin of the tracheoesophageal tract and a shared vagal innervation. Also, patients with respiratory symptoms and pathologic distal esophageal acid exposure but normal proximal esoph-ageal acid exposure may show an improvement in their respiratory symptoms after antireflux therapy.

DIAGNOSIS OF REFLUX-INDUCED ASTHMA

The forme fruste of this condition is establishing the diagnosis. In patients with predominantly reflux symptoms

Figure 1. Odds ratio for pulmonary or laryngeal disease in a large study of military veterans with complicated gastroesophageal reflux disease (data from El-Serag et al21).

Figure 2. A combined proximal (upper) and distal (lower) esophageal pH tracing. The distal probe is positioned 5 cm above the lower esophageal sphincter, the proximal probe 1 cm below the upper esoph-ageal sphincter. (A) A reflux episode to both the proximal and distal esophagus. (B) A reflux episode to the distal esophagus only. There are approximately half the number of proximal reflux events as there are distal events. Each proximal event is preceded or associated with a distal reflux event.

and secondary respiratory complaints, the diagnosis is straightforward. However, in a substantial number of pa-tients with reflux-induced asthma, the respiratory symptoms predominate in the clinical scenario.30 Gastroesophageal

reflux in these patients is often silent and is uncovered only when investigation is initiated. A high index of suspicion is required, notably in patients with poorly controlled asthma despite the use of appropriate pulmonary medications (Ta-ble 1). Supportive evidence for the diagnosis can be gleaned from endoscopy and stationary esophageal manometry. En-doscopy may show erosive esophagitis or Barrett esopha-gus.31Manometry may indicate a hypotensive lower

esoph-ageal sphincter or ineffective body motility, defined as 30% or more contractions in the distal esophagus of 30 mmHg or less in amplitude.32–36

Technetium sulfur colloid scintigraphy has been used to detect microaspiration of gastric contents, but the test has not found favor.22,37– 40 Radioisotope is given either in a

meal or by a nasogastric tube at night. The thorax and abdomen are scanned the next morning. Tracer uptake over the thorax is deemed to indicate aspiration. Studies using scintigraphy have reported a low prevalence of confirmed aspiration among patients with respiratory symptoms and suspected gastroesophageal reflux. The technique probably lacks sufficient sensitivity to be of clinical value.

The gold standard for the diagnosis of reflux-induced asthma is ambulatory dual-probe pH monitoring. One probe

is positioned in the distal esophagus, the other at a more proximal location. The site for this proximal probe place-ment has included the trachea23,24,41; the pharynx42– 45; and

the proximal esophagus, both above and below the upper esophageal sphincter.45,46Three articles reporting on a total

of 30 patients have described simultaneous esophageal and tracheal pH monitoring.23,24,41 These studies were able to

document tracheal acidification after esophageal reflux events. However, in each instance the probes were posi-tioned under general anesthesia. Although this is an appeal-ing technique, patient discomfort will likely limit its wide-spread application. It may be useful in the complex case. Pharyngeal pH monitoring has gained some popularity with ear, nose, and throat surgeons investigating laryngeal dis-orders.42– 45

Most would agree that the proximal esophagus is the preferred site for proximal probe location. It is the least uncomfortable for the patient, especially when positioned below the upper esophageal sphincter. Whether probe placement here should be relative to the upper or lower esophageal sphincter is unclear. Placing the probe 15 cm above the upper border of the lower esophageal sphincter allows assessment of the “height” of reflux. However, probe placement 1 cm below the lower border of the upper esoph-ageal sphincter allows reflux at the highest point in the esophagus to be assessed. In practice, it seems unlikely that the amount of reflux will differ significantly between these two locations, which are within 2 to 4 cm of each other. This is borne out by the similarity of the reference ranges for acid exposure just below the upper esophageal sphincter between different centers (Table 2).

Although ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring allows a direct correlation between esophageal acidification and re-spiratory symptoms, the chronologic relation between reflux events and bronchoconstriction is a complex one. In an attempt to elucidate the nature of this interaction, De-Meester et al33evaluated 77 patients with recalcitrant

respi-ratory complaints (cough, wheezing, pneumonia) suspected of being reflux-related. The following patterns were dis-Table 1. CHARACTERISTIC FEATURES

OF REFLUX-INDUCED ASTHMA Adult onset

Nonsmoker Nonallergic Presence of cough

Predominance of nocturnal crises Worse with meals

Unresponsive to asthma therapy Responsive to antisecretory therapy

Table 2. PUBLISHED REFERENCE RANGES FOR pH MONITORING AT DIFFERENT SITES

Author Probe Location

Control Subjects (no.)

Time Spent at pH<4 (%)

Total Upright Supine

Distal to the UES

Gustafsson (1990)14 15 cm above LES 28* 0.6 0.7 0.8

Dobhan (1993)45 20 cm above LES 26 0.9 1.3 0

Vaezi (1997)46 1 cm below UES 11 1.1 1.7 0.6

Proximal to the UES

Wiener (1989)42 2 cm above UES 12 0 0 0

Paterson (1994)43 1 cm above UES 13 0 0 0

Kuhn (1998)44 2 cm above UES 11 0 0 0

* Pediatric study population.

cerned: reflux episodes preceded or concurred with respira-tory symptoms (22%), respirarespira-tory symptoms preceded re-flux events (16%), and rere-flux events and respiratory symptoms were unrelated (62%). Other reports have de-scribed similar findings,47 with the majority of respiratory symptoms being unrelated chronologically to reflux events. The poor correlation between these two parameters is not entirely unexpected. Wynne et al48 studied the effects of instilling hydrochloric acid (pH 1.5) and gastric juice (pH 1.5 and 5.9) into the trachea of rats. Saline-treated (pH 5.9) animals served as controls. Animals were allowed to re-cover and were killed at various time intervals. The most severe derangements in tracheal morphology and ultrastruc-ture occurred in those treated with gastric juice of pH 1.5. Epithelial desquamation occurred during the initial 48 hours with only partial mucosal regeneration by 1 week. Saline-treated animals had normal tracheal morphology at all time points. Even gastric juice at pH 5.9 caused some cellular loss, although the changes were mild compared with those resulting from instillation of gastric juice or hydrochloric acid solutions at pH 1.5.

If these observations are extrapolated to humans, it is easy to reconcile the high frequency of respiratory symp-toms when the esophageal pH exceeds 4. In this situation, the cough is likely to be caused by the bronchitis induced by infrequent and unrecognized aspiration episodes.

In practice, the diagnosis of reflux-induced asthma is an empirical one, resting on the documentation of increased distal or proximal esophageal acid exposure in patients with pulmonary function test results indicative of asthma. An improvement in respiratory symptoms with antisecretory therapy is additional powerful evidence implicating GERD as the cause of asthma.

DEFINITION OF ASTHMA

The current definition of asthma is based on a 1995 Global Initiative for Asthma/World Health Organization workshop report49 that defined asthma as

a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways in which many cells play a role, in particular mast cells, eosinophils, and T lymphocytes. In susceptible individuals this inflamma-tion causes recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, and cough, particularly at night and/or in the early morning. These symptoms are usually associated with widespread but variable airflow limitation that is at least partly reversible either spontaneously or with treatment. The inflammation also causes an associated increase in airway responsiveness to a variety of stimuli.

Demonstration of this altered airway responsiveness is commonly used as a diagnostic tool, although there is some overlap between the responses of healthy subjects and per-sons with asthma. Perper-sons with asthma typically show a 20% or more change in peak expiratory flow rate (PEF). The presence of reactive airway disease is confirmed if a

reduc-tion in PEF of at least 20% occurs with inhaled histamine or methacholine, or an increase of 20% or more occurs with inhaled bronchodilators.50

TREATMENT OF REFLUX-INDUCED ASTHMA

The concept that therapy for GERD might ameliorate the symptoms of asthma is not a new one. In 1892 Sir William Osler51 remarked on the deleterious effects of gastric

dis-tention in patients with asthma: “Diet, too, has an important influence, and in persons subject to the disease severe par-oxysms may be induced by overloading the stomach, or by taking certain articles of food.” With regard to treatment, he commented that “particular attention should be paid to the diet of asthmatic patients. A rule which experience gener-ally compels them to make is to take the heavy meals in the early part of the day and not to retire to bed before gastric digestion is completed.” In 1960 Belsey52 detailed “The

Pulmonary Complications of Esophageal Disease” in his series of more than 1,300 patients. His findings were sub-stantiated by several other papers published during the 1960s and 1970s that described the association between pulmonary pathology and both hiatal hernia and GERD,18,20,53–55as well as the dramatic relief of respiratory

symptoms after antireflux surgery.17,56 – 63

The 1980s heralded a new era in the treatment of acid-peptic disorders with the introduction of histamine (H2

)-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors. With their increasing use, trials of these agents in patients with reflux-induced asthma were reported.

Medical Therapy

Conservative Measures and Simple Antacids

Three studies have examined the therapeutic value of lifestyle measures and simple antacids. Two of these showed an improvement in asthma symptoms64,65and one

showed no effect.66Kjellen et al,64in the only randomized

study, evaluated 62 patients, 31 assigned to a treatment group and 31 to a control group. After 8 weeks of interven-tion, including elevation of the head of the bed and the use of antacids, dyspnea, wheezing, cough, and expectoration were decreased in 46% to 54% of the treatment group and in 4% to 16% of the control group. A reduction in use of asthma medications occurred in 75% of treated patients and in 42% of controls. Neither group had any improvement in objective measures of pulmonary function.

Prokinetics and H2-Receptor Antagonists

Three uncontrolled studies have examined the effect of cisapride at a dose of 0.8 to 0.9 mg/kg/day in pediatric patients.67– 69 Using symptomatic improvement as an end point, these studies reported an improvement in 83% to 95%

of the children treated. There have been no studies of the value of prokinetics in adult patients with GERD.

There have been nine trials70 –78evaluating the effects of H2-receptor antagonists. In the largest, Ekstrom et al

74

en-rolled 48 patients into a double-blind crossover study of ranitidine 150 mg twice daily for 4 weeks. There were significant reductions in nocturnal respiratory symptoms and the need for inhaled2-agonists. There were no

signif-icant changes in objective parameters of respiratory func-tion. The beneficial effects of therapy occurred in only 27 patients (56%) with a history of reflux-associated respira-tory symptoms, defined as a feeling of respirarespira-tory distress, wheezing, or cough in connection with heartburn or acid regurgitation.

The findings of most other studies of H2-receptor

antag-onists are similar to those of Ekstrom et al, despite wide variations in the duration of therapy (range 4 weeks to⬎1 year). Overall, seven of the nine studies reported a benefi-cial effect on asthma symptoms, with almost half of the treated patients experiencing an improvement in symptoms. PEF was unaltered in all except a study by Goodall et al,70 which found an 8% improvement in the nocturnal PEF. Similarly, forced vital capacity and forced expiratory vol-ume were unchanged in all except one of the studies. Proton Pump Inhibitors

Depla et al79 were the first to report the therapeutic potential of proton pump inhibitors in a 25-year-old man with uncontrolled asthma despite therapy with systemic corticosteroids, inhaled2-agonists and inhaled

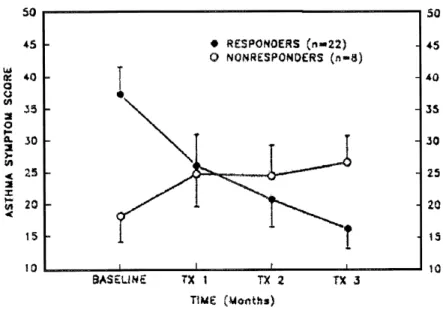

anticholin-ergics. Since this initial report in 1988, there have been six additional studies evaluating the effects of proton pump inhibitors in patients with asthma and GERD (Table 3).80 – 85In the best of the placebo-controlled trials, Meier et al81 studied improvements in pulmonary function in 15 patients with asthma and proven GERD. Success, defined as an improvement of at least 20% in forced expiratory vol-ume, was achieved in 4 of the 15 patients (27%). In the largest study, and the only one to use pH monitoring, Harding et al85 evaluated 30 patients before and after 3

months of omeprazole therapy. The dose of omeprazole was titrated to achieve “normalization” of the 24-hour pH study. An omeprazole dose of 40 mg or greater was required in eight patients (27%) to return esophageal acid exposure to normal. A favorable response to therapy was defined as a reduction of more than 20% in the asthma symptom score, an improvement in PEF of more than 20%, or a reduction in bronchodilator use of more than 20%. A reduction in the daily steroid dose of more than 40% was also considered a significant response. Using these criteria, 22 patients (73%) met at least one of the definitions of response (Figs. 3 and 4). Overall, treatment with omeprazole resulted in improve-ments in symptoms in 67% of patients, pulmonary function in 20%, and medication use in 17%. Four of the 15 patients receiving oral corticosteroids at the beginning of the study reduced their dose by more than 40%.

Overall, three of the six studies using proton pump in-hibitors found a treatment-related improvement in symp-toms. When a benefit was observed, it occurred on average in 25% of the patients. Half of the studies also reported a significant increase in objective measures of pulmonary function. When a benefit was seen, it occurred on average in 13% of patients. In the remaining studies, no beneficial effect was observed.

Antireflux Surgery

Through early reports52,53,63of the surgical treatment of GERD, in particular the work of Belsey,52,63the association between respiratory symptoms and gastroesophageal reflux was recognized. The increasing recognition of this associ-ation was exemplified by a 1967 article57in which Urschel and Paulson noted a 61% prevalence of respiratory symp-toms in patients with GERD. Five years previously, the same group had noted a 10% prevalence of respiratory symptoms.53The authors attributed this sixfold increase to a heightened awareness of the respiratory manifestations of GERD.

Subsequent papers by Overholt and Voorhees,56Babb et al,58 Lomasney,59 and Henderson and Woolfe60 reported Table 3. EFFECTS OF PROTON PUMP INHIBITORS

Study

Patients (no.)

Study Type

Daily Therapy & Duration (weeks)

Improvement in Asthma Parameter

Symptoms Medication Use PEF Spirometry

Ford, 199480 10 RX Omeprazole 20 mg (4) ⫾ ⫾ ⫾ NS Meier, 199481 15 RX Omeprazole 40 mg (6) ⫹ NS ⫹ ⫹ Teichtahl, 199682 20 RX Omeprazole 40 mg (4) ⫾ NS ⫹ ⫾ Harding, 199685 30 U Omeprazole 20–60 mg (13) ⫹ ⫹ ⫹ NS Levin, 199883 9 RX Omeprazole 20 mg (8) ⫹ NS ⫾ ⫾ Boeree, 199884 16 RC Omeprazole 40 mg (13) ⫾ NS ⫾ ⫾

PEF, peak expiratory flow rate; RX, randomized placebo-controlled crossover study; U, uncontrolled study; RC, randomized controlled study.

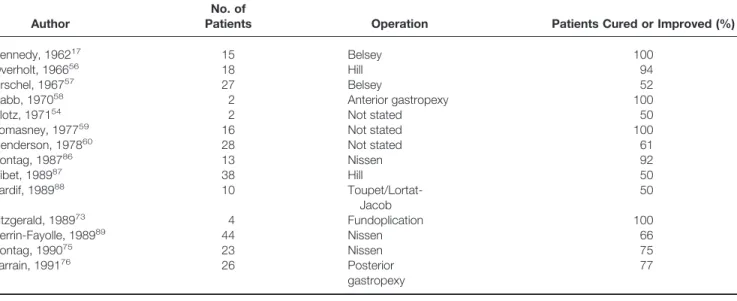

dramatic clinical improvements in some patients with asthma after antireflux surgery (Table 4).

Antireflux Surgery in Children

The outcome after antireflux surgery in children with reflux-induced asthma is summarized in Table 5. In an early study, Berquist et al65compared the outcome of 17 children after Nissen fundoplication with that of 25 children man-aged medically. Medical management, which was given for a minimum of 4 weeks, included elevating the head of the bed, refraining from solids or liquids in the 3 hours before bedtime, and using antacids. Fifteen of the surgically treated patients (76%) had an improvement in symptoms, with complete relief in two patients (12%). In comparison, only 35% of the nonsurgical group improved; no patient in this group was rendered asymptomatic.

In one of the larger studies, Andze et al92 reported the treatment outcome of 105 children with reflux-induced asthma. Medical therapy comprised upright posturing, the use of thickened feedings, and the use of antacids or

pro-kinetics. Patients who failed to respond to medical therapy were referred for fundoplication. Medical therapy was ef-fective in 72 children (69%) and inefef-fective in the remain-ing 33 (31%), who underwent fundoplication. Children younger than 3 years of age had a significantly better response to medical therapy than those 3 years and older (77% vs. 50%). After antireflux surgery, 88% of patients had either an excellent outcome (defined as the need for occasional intermittent medication) or a good outcome (de-fined as a decrease in the frequency of asthma attacks and medication use). After surgery, the annual number of hos-pital admissions (3.2 vs. 0.6), the annual number of emer-gency room visits (5.6 vs. 1.0), the number of asthma medications required, and corticosteroid use (73% vs. 12%) were all significantly reduced.

Antireflux Surgery in Adults

Table 4 summarizes reports of the outcome after antire-flux surgery in adults with asthma. Sontag et al86published the first study that used objective measures of pulmonary

Figure 3. Asthma symptom scores at baseline and after 3 months of therapy with omeprazole. (Left) Se-rial measurements for the 22 patients in whom a sponse to treatment was observed. (Right) Serial re-cordings for the eight patients in whom no substantial response was observed. (Data from Harding et al.85)

Figure 4. Serial mean symptom score for 22 patients with omeprazole-responsive asthma and 8 patients with omeprazole nonresponsive asthma during 3 months of treatment with a dose of omeprazole suf-ficient to normalize esophageal acid exposure. (Data from Harding et al.85)

function before and after fundoplication. Twelve of the 13 patients with asthma were either free of wheezing episodes (n ⫽ 6) or had significantly fewer episodes (n⫽ 6) after fundoplication. Ten of the 11 patients who required bron-chodilator therapy before surgery were able to discontinue their medication (n ⫽ 4) or reduce the dose significantly (n ⫽6). Six of the seven patients dependent on corticoste-roids were able to discontinue treatment (n⫽ 2) or reduce the dose (n ⫽ 4). Objective measures of pulmonary func-tion, including PEF, were significantly improved.

In the best uncontrolled study of surgery for reflux-induced asthma, Perrin-Fayolle et al89 described the long-term outcome of 44 patients after Nissen fundoplication. Follow-up was at least 5 years, with a mean follow-up of 7.9 years. In 29 patients (66%), respiratory symptoms were either cured (25%) or improved (41%). Symptomatic im-provement after surgery was more likely in younger patients (younger than 50 years) than in their older counterparts. Factors that predicted surgical success included nonallergic asthma, nocturnal asthma, and symptomatic improvement with prokinetics and H2-receptor antagonists.

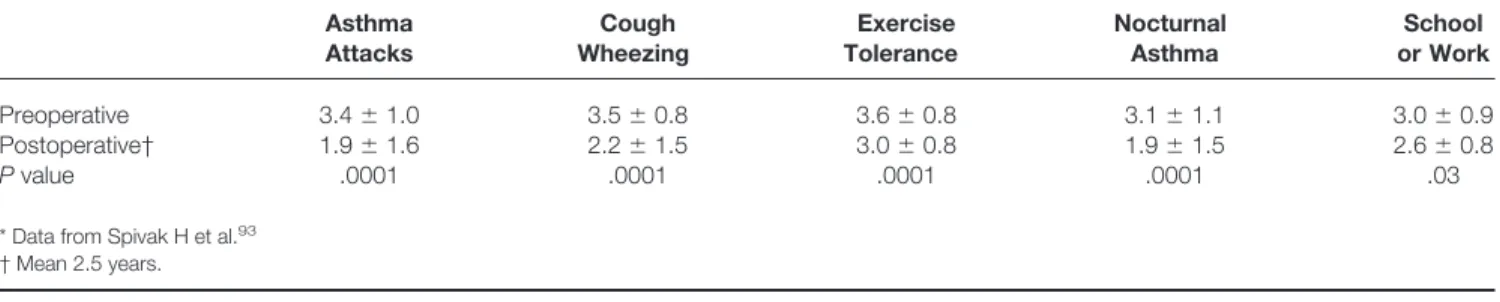

A recent study by Spivak et al93reported the long-term outcome (mean 2.5 years) of 39 patients with asthma after fundoplication (Table 6). After surgery, there were

signifi-cant reductions in the frequency of acute exacerbations and significant improvements in the symptoms of cough and wheezing, coupled with improved exercise tolerance. Fur-ther, the requirements for systemic bronchodilators and corticosteroids were reduced: seven of nine corticosteroid-dependent patients were able to discontinue treatment after surgery.

Antisecretory Therapy Versus Antireflux Surgery

Two randomized controlled trials of surgical versus med-ical antireflux therapy for reflux-induced asthma have been published.75,76In one study patients in the control group had no treatment; in the other they received placebo. Sontag et al75randomized patients to Nissen fundoplication, treatment with ranitidine 150 mg three times daily, or treatment with antacids on an as-needed basis. Asthma was strictly defined as both wheezing and a 20% or more increase in PEF with bronchodilators. The presence of GERD was defined as a positive 24-hour pH score and endoscopic or histologic evidence of esophagitis. Asthma symptom scores and bron-chodilator and steroid use were recorded monthly for 12 months. PEF was recorded for 1 week of each month; Table 4. EFFECTS OF ANTIREFLUX SURGERY IN ADULTS

Author

No. of

Patients Operation Patients Cured or Improved (%)

Kennedy, 196217 15 Belsey 100

Overholt, 196656 18 Hill 94

Urschel, 196757 27 Belsey 52

Babb, 197058 2 Anterior gastropexy 100

Klotz, 197154 2 Not stated 50

Lomasney, 197759 16 Not stated 100

Henderson, 197860 28 Not stated 61

Sontag, 198786 13 Nissen 92 Ribet, 198987 38 Hill 50 Tardif, 198988 10 Toupet/Lortat-Jacob 50 Fitzgerald, 198973 4 Fundoplication 100 Perrin-Fayolle, 198989 44 Nissen 66 Sontag, 199075 23 Nissen 75 Larrain, 199176 26 Posterior gastropexy 77

Table 5. EFFECTS OF ANTIREFLUX SURGERY IN CHILDREN

Author

No. of

Patients Operation Patients Cured or Improved (%)

Berquist, 198165 24 Nissen 92

Johnson, 198490 5 Nissen/gastropexy 80

Buts, 198691 2 Fundoplication 100

Andze, 199192 33 Nissen/Toupet 88

respiratory function tests, esophageal manometry, and en-doscopy were repeated annually. Follow-up was a minimum of 1 year.

Symptoms were completely relieved or improved in 75% of the surgically treated patients, 9% of those treated with H2-receptor antagonists, and 4% of the untreated controls

(Fig. 5). In contrast, asthma symptoms deteriorated in 48% of control subjects, 36% of patients treated with H2

-antag-onists, and 6% of surgically treated patients. Steroid therapy could be discontinued in 33% of the surgically treated patients, 11% of the ranitidine-treated patients, and none of the control subjects. A beneficial effect on PEF was ob-served significantly more frequently in patients treated by fundoplication compared with the other two groups. Six months after fundoplication, one third of the surgical pa-tients had experienced a 10% or greater improvement in maximal PEF, and these benefits were still evident 24 months after surgery.

In the only other randomized study, Larrain et al76 as-signed patients to posterior gastropexy, cimetidine 300 mg four times daily, or placebo. Patients with allergic asthma, defined as positive skin test results to common allergens, were excluded. Asthma was defined by symptoms and either a reduction in PEF of more than 20% after inhaled metha-choline or an increase in PEF of more than 20% after inhaled bronchodilators. GERD was defined as the demon-stration of free reflux on a barium meal examination or as reflux into the distal esophagus of hydrochloric acid

in-stilled into the stomach. This study can be criticized for the use of a gastropexy, which provides less of an antireflux barrier than a fundoplication, and for the relatively nonspe-cific criteria by which GERD was defined. Individual symp-toms were assessed using linear analog scales, from which a composite score was derived.

Composite symptom scores were improved in all three groups, with the greatest improvement seen after surgery. The composite score for medication use was markedly reduced in patients undergoing surgery and slightly reduced in patients receiving cimetidine. Overall, 77% of the surgi-cally treated patients, 74% of the cimetidine-treated pa-tients, and 36% of the placebo-treated patients had reduced wheezing. Complete relief of respiratory symptoms was reported by 35% of the surgically treated patients, 48% of the cimetidine-treated patients, and 4% of the placebo-treated patients. At the 6-month follow-up there were no significant improvements in objective measures of pulmo-nary function. Discontinuation of cimetidine resulted in a prompt return of symptoms. In contrast, 50% of surgically treated patients were free from symptoms more than 5 years after surgery. Virtually none of the placebo-treated patients were asymptomatic. The initial reduction in asthma medi-cation use seen at 6 months persisted in the postsurgical patients. In contrast, patients who had received placebo required increasing medication doses with time.

In summary, antireflux surgery improved respiratory symptoms in nearly 90% of children and 70% of adults with asthma and GERD. Objective improvements in pulmonary function were demonstrated in approximately one third of patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Does Medical Therapy Improve Asthma Control?

Most of the trials of medical therapy enrolled only small numbers of patients and are thus limited by having insuffi-cient statistical power. Further, most studies used relatively short courses of antisecretory therapy (3 months or less). This period may have been sufficient for symptomatic im-provement but insufficient for recovery of pulmonary func-tion, which may take up to 1 year. Mindful of these facts, Table 6. ASTHMA SYMPTOM SCORES BEFORE AND AFTER FUNDOPLICATION (NIH)*

Asthma Attacks Cough Wheezing Exercise Tolerance Nocturnal Asthma School or Work Preoperative 3.4⫾1.0 3.5⫾0.8 3.6⫾0.8 3.1⫾1.1 3.0⫾0.9 Postoperative† 1.9⫾1.6 2.2⫾1.5 3.0⫾0.8 1.9⫾1.5 2.6⫾0.8 Pvalue .0001 .0001 .0001 .0001 .03

* Data from Spivak H et al.93 † Mean 2.5 years.

Figure 5. Outcome in patients treated with fundoplication or ranitidine compared with untreated controls. Outcome was termed cure, marked improvement, improvement, or not improved. Response to treatment was determined after 12 months of therapy. (Data from Sontag et al.75)

the literature indicates that amelioration of respiratory symptoms can be anticipated in 25% to 50% of patients with reflux-induced asthma treated with antisecretory medica-tions. Fewer than 15%, however, can be expected to have objective improvement in pulmonary function. In the best study of antisecretory therapy and the only one to use what would currently be considered optimal treatment, Harding et al85 reported symptomatic and pulmonary function

im-provements in 67% and 20% of patients, respectively. This study may more accurately reflect the true therapeutic value of antisecretory therapy.

If Yes, What is the Optimal Medication and Dosage?

The chances of success with medical treatment are likely to be related directly to the extent of reflux elimination. The conflicting findings of reports of antisecretory therapy may well be due to the inadequate control of gastroesophageal reflux in some studies. Only one study85used on-treatment pH monitoring to ensure adequate acid suppression. Of note, 27% of patients required an omeprazole dose of 40 mg or greater to control reflux.

In patients with GERD, esophageal acid exposure is reduced by up to 80% with H2-receptor antagonists

94 –98

and up to 95% with proton pump inhibitors.95,98,99Despite the superiority of the latter class of drug over the former, emerging evidence suggests that periods of acid break-through still occur.100,101They are most common at night and provide some justification for a split rather than a single dosing regimen. Katzka et al100 studied 45 patients with breakthrough reflux symptoms while taking omeprazole (20 mg twice daily) and found that 36 patients were still having reflux, defined as a total distal esophageal acid exposure of more than 1.6%. Peghini et al101used intragastric pH mon-itoring in 28 healthy volunteers and 17 patients with GERD and identified nocturnal recovery of acid secretion (⬎1 hour) in 75% of studied subjects. Recovery of acid secretion occurred within 12 hours of the oral evening dose of proton pump inhibitor, the median recovery time being 7.5 hours. This is pertinent because it is during the night and early morning that asthma symptoms are most pronounced and that PEF is at its lowest. The same group102 also showed that ranitidine 300 mg at bedtime is superior to omeprazole 20 mg at bedtime in preventing acid breakthrough. The authors speculated that this observation was related to the abolition of histamine-mediated acid secretion in the fasting state.

Ideally, antisecretory therapy should be tailored to the patient by using dual gastric and esophageal pH monitoring during treatment, adjusting the dosage accordingly. How-ever, limited resources and financial constraints may well mandate empirical therapy. In this setting, the optimal an-tisecretory therapy comprises a proton pump inhibitor twice daily, one tablet before breakfast and the other before the

evening meal, along with a single dose of an H2-receptor

antagonist before bedtime.95

Does Antireflux Surgery Improve Asthma Control?

The literature indicates that antireflux surgery improves respiratory symptoms in nearly 90% of children and 70% of adults with asthma and GERD. Improvements in pulmonary function were demonstrated in approximately one third of patients.

Is Surgery Superior to Medical Therapy? Antireflux surgery has been shown to ameliorate respira-tory symptoms consistently in patients with reflux-induced asthma, and the results are superior to the published trials of antisecretory therapy. However, in the one medical study that used what would currently be considered optimal anti-secretory therapy, the success rate was comparable to that seen after fundoplication. This suggests that medical ther-apy may achieve similar results to surgery, although large studies to provide support for this assertion are lacking. Definitive large-scale studies comparing longer courses of antisecretory therapy (up to 12 months) with fundoplication are awaited.

The potential advantage of surgery over medical therapy is that the reduction in esophageal acid exposure is greater, at up to 98%,96 –98with equivalent protection being afforded throughout the circadian cycle. There are thus no concerns about nocturnal acid breakthrough. Moreover, a reduction in esophageal exposure to a pH of less than 4 by antisecretory medications may not be synonymous with a reduction in reflux.100 It may merely signify reflux of a more alkaline gastric juice. The antireflux machinery is still defective in medically treated patients with GERD. Experimental animal studies of the effects of gastric juice on the trachea show that even when the pH is 5.9, significant injury to the tracheal mucosa can occur.

It is also important to realize that in patients with asthma with a nonreflux-induced motility abnormality of the esoph-ageal body, performing an antireflux operation may result in the aspiration of orally regurgitated, swallowed liquid or food. This can result in respiratory symptoms and airway irritation that may elicit an asthmatic reaction. This factor may be why surgical results appear to be better in children than adults, because disturbance of esophageal body motil-ity is more likely in adult patients.

References

1. Howard PJ, Heading RC. Epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Surg 1992; 16:288 –293.

2. Locke GR, Talley NJ, Fett SL, et al. Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology 1997; 112:1448 –1456.

3. Adams R, Ruffin R, Wakefield M, et al. Asthma prevalence, mor-bidity and management practices in South Australia, 1992–1995. Aust NZ J Med 1997; 27:672– 679.

4. Farber HJ, Wattigney W, Berenson G. Trends in asthma prevalence: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1997; 78:265–269.

5. Lewis S, Hales S, Slater T, et al. Geographical variation in the prevalence of asthma symptoms in New Zealand. NZ Med J 1997; 110:286 –289.

6. Neukirch F, Pin I, Knani J, et al. Prevalence of asthma and asthma-like symptoms in three French cities. Respir Med 1995; 89:685– 692. 7. Austin JB, Russell G, Adam MG, et al. Prevalence of asthma and wheeze in the Highlands of Scotland. Arch Dis Child 1994; 71:211– 216.

8. Campbell K, Davis J, Kingston H, Milne GA. An all age group study of the prevalence of asthma in Golden Bay. NZ Med J 1993; 106: 282–283.

9. Capewell S. Asthma in Scotland: epidemiology and clinical manage-ment. Health Bull 1993; 51:118 –127.

10. Gellert AR, Gellert SL, Iliffe SR. Prevalence and management of asthma in a London inner city general practice. Br J Gen Pract 1990; 40:197–201.

11. Gerstman BB, Bosco LA, Tomita DK, et al. Prevalence and treatment of asthma in the Michigan Medicaid patient population younger than 45 years, 1980 –1986. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1989; 83:1032–1039. 12. Burr ML, Butland BK, King S, Vaughan-Williams E. Changes in asthma prevalence: two surveys 15 years apart. Arch Dis Child 1989; 64:1452–1456.

13. Sontag SJ, O’Connell S, Khandelwal S, et al. Most asthmatics have gastroesophageal reflux with or without bronchodilator therapy. Gas-troenterology 1990; 99:613– 620.

14. Gustafsson PM, Kjellman NIM, Tibbling L. Bronchial asthma and acid reflux into the distal and proximal oesophagus. Arch Dis Child 1990; 65:1255–1258.

15. Vincent D, Cohn-Jonathan AM, Leport J, et al. Gastro-oesophageal reflux prevalence and relationship with bronchial reactivity in asthma. Eur Respir J 1997; 10:2255–2259.

16. Balson BM, Kravitz EKS, McGeady SJ. Diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux in children and adolescents with severe asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1998; 81:159 –164. 17. Kennedy JH. Silent gastroesophageal reflux: an important but little

known cause of pulmonary complications. Dis Chest 1962; 42:42– 45.

18. Mays EE. Intrinsic asthma in adults associated with gastroesophageal reflux. JAMA 1976; 236:2626 –2628.

19. Gastal OL, Castell JA, Castell DO. Frequency and site of gastro-esophageal reflux in patients with chest symptoms. Chest 1994; 106:1793–1796.

20. Mays EE, Dubois JJ, Hamilton GB. Pulmonary fibrosis associated with tracheobronchial aspiration. A study of the frequency of hiatal hernia and gastroesophageal reflux in interstitial pulmonary fibrosis of obscure etiology. Chest 1976; 69:512–515.

21. El-Serag HB, Sonnenberg A. Comorbid occurrence of laryngeal or pulmonary disease with esophagitis in United States military veter-ans. Gastroenterology 1997; 113:755–760.

22. Ruth M, Carlsson S, Mansson I, et al. Scintigraphic detection of gastropulmonary aspiration in patients with respiratory disorders. Clin Physiol 1993; 13:19 –33.

23. Jack CIA, Calverley PMA, Donnelly RJ, et al. Simultaneous tracheal and oesophageal pH measurements in asthmatic patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux. Thorax 1995; 50:201–204.

24. Donnelly RJ, Berrisford RG, Jack CIA, et al. Simultaneous tracheal and esophageal pH monitoring: investigating reflux-associated asthma. Ann Thorac Surg 1993; 56:1029 –1034.

25. Tuchman DN, Boyle JT, Pack AI, et al. Comparison of airway responses following tracheal or esophageal acidification in the cat. Gastroenterology 1984; 87:872– 881.

26. Mansfield LE, Stein MR. Gastroesophageal reflux and asthma: a possible reflex mechanism. Ann Allergy 1978; 41:224 –226. 27. Mansfield LE, Hameister HH, Spaulding HS, et al. The role of the

vagus nerve in airway narrowing caused by intraesophageal hydro-chloric acid provocation and esophageal distention. Ann Allergy 1981; 47:431– 434.

28. David RS, Larsen GL, Grunstein MM. Respiratory response to in-traesophageal acid infusion in asthmatic children during sleep. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1983; 72:393–398.

29. Wright WA, Miller SA, Corsello BF. Acid-induced esophagobron-chial-cardiac reflexes in humans. Gastroenterology 1990; 99:71–73. 30. Irwin RS, Curley FJ, French CL. Difficulty to control asthma. Con-tributing factors and outcome of a systematic management protocol. Chest 1993; 103:1662–1669.

31. Sontag SJ, Schnell TG, Miller TQ, et al. Prevalence of oesophagitis in asthmatics. Gut 1992; 33:872– 876.

32. Fouad YM, Katz PO, Hatlebakk JG, Castell DO. Ineffective esoph-ageal motility: the most common motility abnormality in patients with GERD-associated respiratory symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:1464 –1467.

33. DeMeester TR, Bonavina L, Iascone C, et al. Chronic respiratory symptoms and occult gastroesophageal reflux. A prospective clinical study and results of surgical therapy. Ann Surg 1990; 211:337–345. 34. Patti MG, Debas HT, Pellegrini CA. Esophageal manometry and 24-hour pH monitoring in the diagnosis of pulmonary aspiration secondary to gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Surg 1992; 163::401– 406.

35. Johnson WE, Hagen JA, DeMeester TR, et al. Outcome of respiratory symptoms after antireflux surgery on patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Arch Surg 1996; 131:489 – 492.

36. Campo S, Morini S, Antonietta M, et al. Esophageal dysmotility and gastroesophageal reflux in intrinsic asthma. Dig Dis Sci 1997; 42: 1184 –1188.

37. Reich SB, Earley WC, Ravin TH, et al. Evaluation of gastro-pulmo-nary aspiration by a radioactive technique. J Nucl Med 1977; 18: 1079 –1081.

38. Ghaed N, Stein MR. Assessment of a technique for scintigraphic monitoring of pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents in asthmatics with gastroesophageal reflux. Ann Allergy 1979; 42:306 –308. 39. Crausaz FM, Favez G. Aspiration of solid food particles into lungs of

patients with gastroesophageal reflux and chronic bronchial disease. Chest 1988; 93:376 –378.

40. Fawcett HD, Hayden CK, Adams JC, Swischuk LE. How useful is gastroesophageal reflux scintigraphy in suspected childhood aspira-tion. Pediatr Radiol 1988; 18:311–313.

41. Hue V, Leclerc F, Gottrand F, et al. Simultaneous tracheal and oesophageal pH monitoring during mechanical ventilation. Arch Dis Child 1996; 75:46 –50.

42. Wiener GJ, Koufman JA, Wu WC, et al. Chronic hoarseness second-ary to gastroesophageal reflux disease: documentation with 24-h ambulatory pH monitoring. Am J Gastroenterol 1989; 84:1503–1508. 43. Paterson WG, Murat BW. Combined ambulatory esophageal manom-etry and dual-probe pH-mmanom-etry in evaluation of patients with chronic unexplained cough. Dig Dis Sci 1994; 39:1117–1125.

44. Kuhn J, Toohill RJ, Ulualp SO, et al. Pharyngeal acid reflux events in patients with vocal cord nodules. Laryngoscope 1998; 108:1146 – 1149.

45. Dobhan R, Castell DO. Normal and abnormal proximal esophageal acid exposure: results of ambulatory dual-probe pH monitoring. Am J Gastroenterol 1993; 88:25–29.

46. Vaezi MF, Schroeder PL, Richter JE. Reproducibility of proximal probe pH parameters in 24-hour ambulatory esophageal pH monitor-ing. Am J Gastroenterol 1997; 92:825– 829.

47. Laukka MA, Cameron AJ, Schei AJ. Gastroesophageal reflux and chronic cough: which comes first? J Clin Gastroenterol 1994; 19: 100 –104.

48. Wynne JW, Ramphal R, Hood CI. Tracheal mucosal damage after aspiration. A scanning electron microscope study. Am Rev Respir Dis 1981; 124:728 –732.

49. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Manage-ment and Prevention: NHLBI/WHO Workshop Report. National In-stitutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 1995. 50. Barnes PJ, Grunstein MM, Leff AR, Woolcock AJ, eds. Asthma.

Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997.

51. Osler W. Bronchial asthma. In: The principles and practice of med-icine. Edinburgh: Young J. Pentland; 1892.

52. Belsey R. The pulmonary complications of oesophageal disease. Br J Dis Chest 1960; 54:342–348.

53. Paulson DL, Shaw RR, Kee JL. Esophageal hiatal diaphragmatic hernia and its complications. Ann Surg 1962; 155:957–970. 54. Klotz SD, Moeller RK. Hiatal hernia and intractable bronchial

asthma. Ann Allergy 1971; 29:325–328.

55. Euler AR, Byrne WJ, Ament ME, et al. Recurrent pulmonary disease in children: a complication of gastroesophageal reflux. Pediatrics 1979; 63:47–51.

56. Overholt RH, Voorhees RJ. Esophageal reflux as a trigger in asthma. Dis Chest 1966; 49:464 – 466.

57. Urschel HC, Paulson DL. Gastroesophageal reflux and hiatal hernia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1967; 53:21–32.

58. Babb RR, Notarangelo J, Smith VM. Wheezing: a clue to gastro-esophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol 1970; 53:230 –233. 59. Lomasney TL. Hiatus hernia and the respiratory tract. Ann Thorac

Surg 1977; 24:448 – 450.

60. Henderson RD, Woolfe CR. Aspiration and gastroesophageal reflux. Can J Surg 1978; 21:352–354.

61. Pellegrini CA, DeMeester TR, Johnson LF, Skinner DB. Gastro-esophageal reflux and pulmonary aspiration: incidence, functional abnormality, and results of surgical therapy. Surgery 1979; 86:110 – 118.

62. Davis MV, Fiuzat J. Application of the Belsey hiatal hernia repair to infants and children with recurrent bronchitis, bronchiolitis, and pneumonitis due to regurgitation and aspiration. Ann Thorac Surg 1967; 3:99 –110.

63. Skinner DB, Belsey RHR. Surgical management of esophageal reflux and hiatus hernia. Long-term results with 1030 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1967; 53:33–50.

64. Kjellen G, Tibbling L, Wranne B. Effect of conservative treatment of oesophageal dysfunction on bronchial asthma. Eur J Resp Dis 1981; 62:190 –197.

65. Berquist WE, Rachelefsky GS, Kadden M, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux-associated recurrent pneumonia and chronic asthma in chil-dren. Pediatrics 1981; 68:29 –35.

66. Shapiro GG, Christie DL. Gastroesophageal reflux in steroid-depen-dent asthmatic youths. Pediatrics 1979; 63:207–212.

67. Saye Z, Forget PP. Effect of cisapride on esophageal pH monitoring in children with reflux-associated bronchopulmonary disease. J Pe-diatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1989; 8:327–332.

68. Tucci F, Resti M, Fontana R, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux and bronchial asthma: prevalence and effect of cisapride therapy. J Pe-diatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1993; 17:265–270.

69. Blecker U, de Pont SMHB, Hauser B, et al. The role of “occult” gastroesophageal reflux in chronic pulmonary disease in children. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 1995; 58:348 –352.

70. Goodall RJR, Earis JE, Cooper DN, et al. Relationship between asthma and gastro-oesophageal reflux. Thorax 1981; 36:116 –121. 71. Harper PC, Bergner A, Kaye DM. Antireflux treatment for asthma.

Improvement with associated gastroesophageal reflux. Arch Intern Med 1987; 147:56 – 60.

72. Nagel RA, Brown P, Perks WH, et al. Ambulatory pH monitoring of gastro-oesophageal reflux in “morning dipper” asthma. Br Med J 1988; 297:1371–1373.

73. Fitzgerald JM, Allen CJ, Craven MA, Newhouse MT. Chronic cough and gastroesophageal reflux. CMAJ 1989; 140:520 –524.

74. Ekstrom T, Lindgren BR, Tibbling L. Effects of ranitidine treatment on patients with asthma and a history of gastro-oesophageal reflux: a double-blind crossover study. Thorax 1989; 44:19 –23.

75. Sontag SJ, O’Connell S, Khandelwal S, et al. Antireflux surgery in asthmatics with reflux (GER) improves pulmonary symptoms and function [abstract]. Gastroenterology 1990; 98:A128.

76. Larrain A, Carrasco E, Galleguillos F, et al. Medical and surgical treatment of nonallergic asthma associated with gastroesophageal reflux. Chest 1991; 99:1330 –1335.

77. Gustafsson PM, Kjellman NIM, Tibbling L. A trial of ranitidine in asthmatic children and adolescents with or without pathological gas-tro-oesophageal reflux. Eur Resp J 1992; 5:201–206.

78. Eid NS, Shepherd RW, Thomson MA. Persistent wheezing and gastroesophageal reflux in infants. Pediatr Pulmonol 1994; 18:39 – 44.

79. Depla AC, Bartelsman JF, Roos CM, et al. Beneficial effect of omeprazole in a patient with severe bronchial asthma and gastro-oesophageal reflux. Eur Respir J 1988; 1:966 –968.

80. Ford GA, Oliver PS, Prior JS, et al. Omeprazole in the treatment of asthmatics with nocturnal symptoms and gastro-oesophageal reflux: a placebo-controlled cross-over study. Postgrad Med J 1994; 70:350 – 354.

81. Meier JH, McNally PR, Punja M, et al. Does omeprazole (Prilosec) improve respiratory function in asthmatics with gastroesophageal reflux ? A double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. Dig Dis Sci 1994; 39:2127–2133.

82. Teichtahl H, Yeomans ND, Kronborg IJ, Robinson P. Adult asthma and gastro-oesophageal reflux: the effects of omeprazole therapy on asthma. Aust NZ J Med 1996; 26:671– 676.

83. Levin TR, Sperling RM, McQuaid KR. Omeprazole improves peak expiratory flow rate and quality of life in asthmatics with gastro-esophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol 1998; 93:1060 –1063. 84. Boeree MJ, Peters FTM, Postma DS, Kleibeuker JH. No effects of

high-dose omeprazole in patients with severe airway hyperrespon-siveness and (a)symptomatic gastro-oesophageal reflux. Eur Respir J 1998; 11:1070 –1074.

85. Harding SM, Richter JE, Guzzo MR, et al. Asthma and gastroesoph-ageal reflux: acid suppressive therapy improves asthma outcome. Am J Med 1996; 100:395– 405.

86. Sontag S, O’Connell S, Greenlee H, et al. Is gastroesophageal reflux a factor in some asthmatics. Am J Gastroenterol 1987; 82:119 –126. 87. Ribet M, Pruvot FR, Mensier E, et al. Gastro-oesophageal reflux and respiratory disorders treated by Hill’s procedure. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1989; 3:414 – 418.

88. Tardif C, Nouvet G, Denis P, et al. Surgical treatment of gastroesoph-ageal reflux in ten patients with severe asthma. Respiration 1989; 56:110 –115.

89. Perrin-Fayolle M, Gormand F, Braillon G, et al. Long-term results of surgical treatment for gastroesophageal reflux in asthmatic patients. Chest 1989; 96:40 – 45.

90. Johnson DG, Syme WC, Matlak ME, et al. Gastro-oesophageal reflux and respiratory disease: the place of the surgeon. Aust NZ J Surg 1984; 54:405– 415.

91. Buts JP, Barudi C, Moulin D, et al. Prevalence and treatment of silent gastro-oesophageal reflux in children with recurrent respiratory dis-orders. Eur J Pediatr 1986; 145:396 – 400.

92. Andze GO, Brandt ML, St. Vil D, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux in 500 children with respiratory symptoms: the value of pH monitoring. J Pediatr Surg 1991; 26:295–300. 93. Spivak H, Smith CD, Phichith A, et al. Asthma and gastroesophageal

reflux: fundoplication decreases the need for systemic corticosteroids [abstract]. Gastroenterology 1998; 114:A1428.

94. DeMeester TR, Johnson LF, Bonavina L. Medical therapy of gastro-esophageal reflux disease assessed by 24-hour gastro-esophageal pH mon-itoring. Dis Esophagus 1990; 1152–1162.

95. Fiorucci S, Santucci L, Morelli A. Effect of omeprazole and high doses of ranitidine on gastric acidity and gastroesophageal reflux in

patients with moderate-severe esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1990; 85:1458 –1462.

96. Orr WC, Finn A, Wilson T, Russell J. Esophageal acid contact time and heartburn in acute treatment with ranitidine and metoclopramide. Am J Gastroenterol 1990; 85:697–700.

97. Russell J, Orr WC, Wilson T, Finn AL. Effects of ranitidine, given tds, on intragastric and oesophageal pH in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux. Aliment Pharmacol Therap 1991; 5:621– 630. 98. Cucchiara S, Minella R, Iervolino C, et al. Omeprazole and high dose

ranitidine in the treatment of refractory reflux oesophagitis. Arch Dis Child 1993; 69:655– 659.

99. Robinson M, Maton PN, Allen ML, et al. Effect of different doses of omeprazole on 24-hour oesophageal acid exposure in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux. Aliment Pharmacol Therap 1991; 5:645– 651. 100. Katzka DA, Paoletti V, Leite L, Castell DO. Prolonged ambulatory pH monitoring in patients with persistent gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: testing while on therapy identifies the need for more aggres-sive anti-reflux therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91:2110 –2113. 101. Peghini PL, Katz PO, Bracy NA, Castell DO. Nocturnal recovery of

gastric acid secretion with twice-daily dosing of proton pump inhib-itors. Am J Gastroenterol 1998; 93:763–767.

102. Peghini PL, Katz PO, Castell DO. Ranitidine controls nocturnal gastric acid breakthrough on omeprazole: a controlled study in nor-mal subjects. Gastroenterology 1998; 115:1335–1339.

103. Fouad YM, Katz PO, Castell DO. Adding ranitidine at bedtime controls nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux (GER) in patients taking proton pump inhibitors twice daily. Gastroenterology 1999;116: A208.

104. Hunter JG, Trus TL, Branum GD, et al. A physiologic approach to laparoscopic fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Surg 1996; 223:673– 687.

105. Peters JH, DeMeester TR, Crookes P, et al. The treatment of gastro-esophageal reflux disease with laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Ann Surg 1998; 228:40 –50.

106. DeMeester TR, Johnson LF. Evaluation of the Nissen antireflux procedure by esophageal manometry and twenty-four hour pH mon-itoring. Am J Surg 1975; 129:94 –100.

107. Vela M, Camacho-Lobato L, Hatlebakk J, et al. Effect of omeprazole (PPI) on ratio of acid to nonacid gastroesophageal reflux. Studies using simultaneous intraesophageal impedance and pH measurement. Gastroenterology 1999;116:A209.