Patients’ Needs Assessment Tools in

Cancer Care:

Principles & Practice

July 2005

Alison Richardson

Jibby Medina

Ann Richardson

King’s College London

John Sitzia

Vivienne Brown

Worthing and Southlands

Hospital NHS Trust

This report was commissioned by the Department of Health and the Cancer Action Team.

This report should be referenced as: Richardson A, Sitzia J, Brown V, Medina J, Richardson A. (2005) “Patients’ Needs Assessment Tools in Cancer Care: Principles and Practice”. London: King’s College London

Contents

1. INTRODUCTION... 1

Aims... 1

Background... 2

Methods ... 4

2. THE LITERATURE REVIEW... 6

The Tools ... 6

Purpose and population... 12

Content... 12

Question format and scoring ... 16

Validity... 17

Reliability ... 17

Responsiveness ... 18

Feasibility ... 18

Summary of tool evaluation ... 20

The Impact of Assessment Tools... 20

3. THE SCOPING EXERCISE... 23

Cancer Networks’ Response To Developing A Unified Approach: An Overview... 23

The development of policy and guidance on patient needs assessment... 24

Network leadership on patient needs assessment ... 25

Engaging with key stakeholders ... 26

Network Patient Needs Assessment: An Overview... 26

Specific assessment tools or approaches identified ... 26

Assessment development ... 27

Domains covered by network assessments ... 28

Type of assessment ... 28

The point at which assessments are made ... 29

Patient groups assessed ... 30

The process of selecting an assessment tool or approach... 30

Perceived benefits and limitations of identified assessment tools or approaches ... 31

Perceived cost implications of assessments ... 32

Perceived training requirements of assessments ... 32

How Assessment Tools Are Used In Clinical Practice ... 32

Who carries out the assessment? ... 32

Assessment method... 33

Assessment and recording format... 33

Setting in which assessments are completed... 33

Average completion time ... 33

Revisiting the assessment... 33

4. LEARNING FROM THE SINGLE ASSESSMENT PROCESS ... 36

Introduction ... 36

SAP Assessment Tools And Assessment Scales ... 37

The Aim Of The Research ... 37

Key Themes... 37

The ‘framework’ approach ... 37

The diversity of tools... 38

Electronic solutions ... 39

Inter-agency working ... 40

Some Recommendations... 41

5. REFLECTIONS ON PATIENT ASSESSMENT TOOLS AND APPROACHES .. 42

The Assessment Process ... 42

Purpose ... 42

Scope ... 44

Developing Assessment Tools... 44

Tools and frameworks ... 45

Features of tools... 45

The views of networks ... 46

Key issues ... 46

Using Assessment Tools... 47

Acceptability ... 47

Practical issues ... 49

Interagency working ... 49

Training ... 50

Options For The Department of Health and Cancer Action Team... 51

Conclusion ... 55

6. REFERENCES ... 56

7. ANNEXES ... 62

Annex 1. Research methods: A technical report ... 63

Annex 2. Directory of tools ... 76

The CARES... 76

The CCM ... 77

The CHOICES assessment... 79

The concerns checklist ... 80

The distress management tool ... 84

The IHA ... 85 The NEQ ... 86 The NEST... 89 The OCPC... 92 The PNAT... 95 The PNPC ... 101

The SCNS ... 108

The SPARC... 112

The symptoms and concerns checklist... 117

Annex 3. The questionnaires used in the scoping exercise ... 119

Questionnaire A... 120

Questionnaire B... 122

Annex 4. The Single Assessment Framework for Older People ... 126

Figures, Tables and Boxes

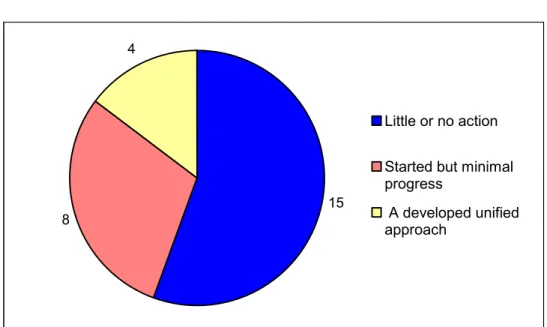

Figure 1. Stage in the development of a unified approach ... 24

Figure 2. Policy and guidance ... 24

Figure 3. The identified lead ... 25

Figure 4. Domains covered by the assessment tool ... 28

Figure 5. The point at which the assessment is made... 29

Figure 6. The patient group assessed ... 30

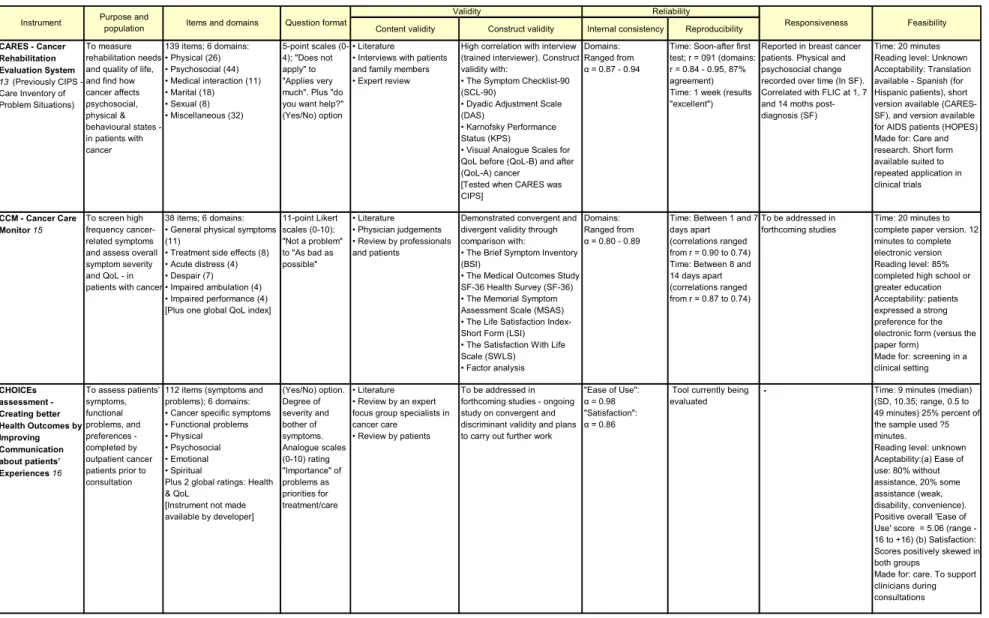

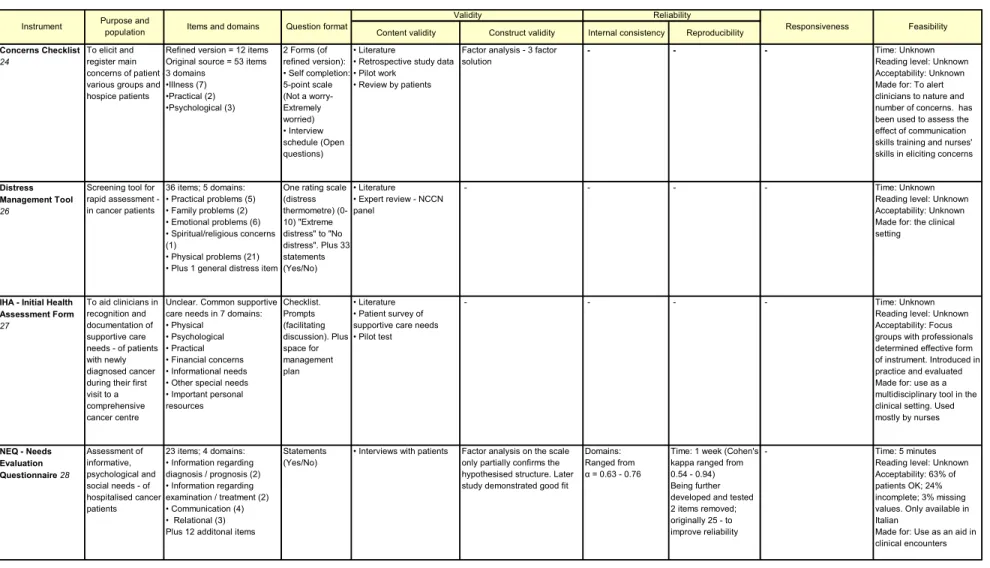

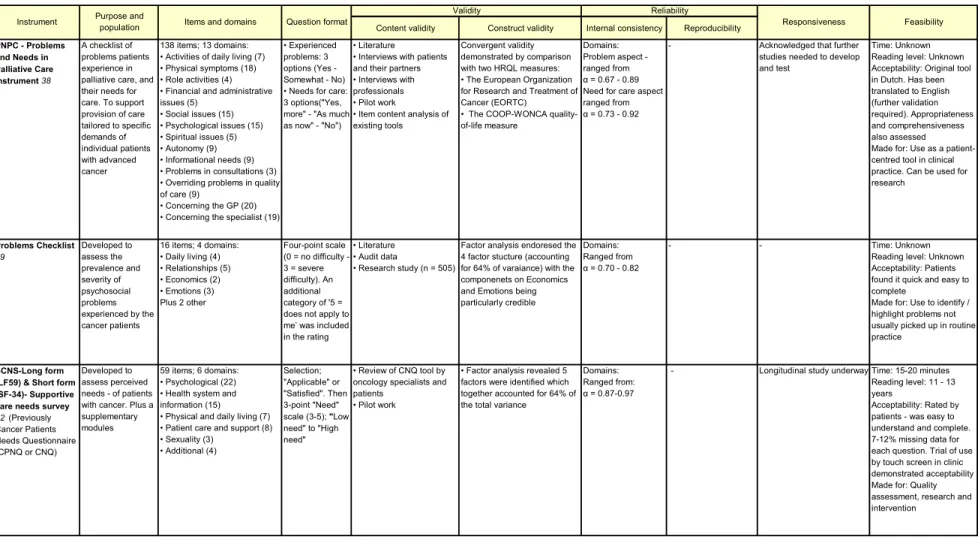

Table 1. Summary of tool properties... 7

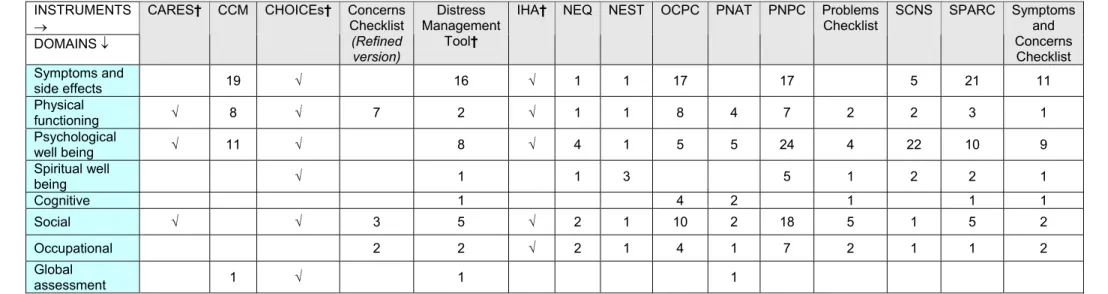

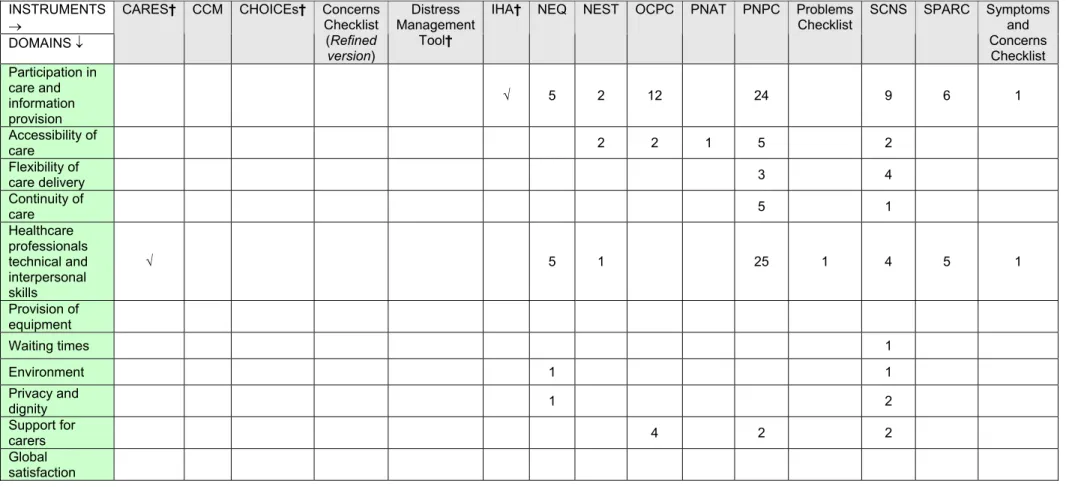

Table 2. Comparison of content of assessment instruments compared by reference to needs related to health status... 14

Table 3. Comparison of content of assessment instruments compared by reference to needs for and satisfaction with health care... 15

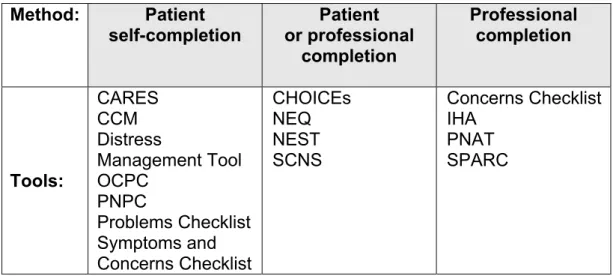

Table 4. Method of tool administration... 18

Table 5. Method of tool completion... 19

Table 6. Off the shelf assessment tools identified by cancer networks... 27

1. INTRODUCTION

Aims

There is currently considerable interest in developing tools for assessing the broad needs of patients with cancer. The Department of Health (DH) and the Cancer Action Team (CAT) have made a commitment to support a process to inform the

development of patient needs assessment approaches or tools for use in routine practice. As part of this process, research was commissioned to scope aspects of patient needs assessment and explore key issues that might impinge on the

development of an approach or tool; this includes some options on different models that might be pursued in order to reach a unified approach to assessment within a cancer network. This report is based on three strands of research: a rapid appraisal of the relevant literature, a scoping exercise on the actual use of assessment tools

among networks and discussions with those involved in the Single Assessment Process for older people to learn appropriate lessons from this context.

A working definition of patient needs assessment was developed early in the project, with an expectation that this might be refined as the appraisal unfolded. Assessment is about collecting information on a person’s needs and circumstances, and making sense of that information in order to identify needs and decide on what support or treatment to offer1. It was conceived as (i) a clearly defined process, done with, or by, the person with (or suspected as having) cancer; (ii) involving some form of consistent framework; (iii) involving regular comprehensive assessment at clearly defined

intervals; (iv) based on patients’ accounts of their needs and wishes which they expect professional care to meet; and finally (v) informing the decisions of a range of health care professionals involved in cancer care.

A patient needs assessment tool is defined here as a collection of questions, scales and other means of obtaining information which together provide a consistent and comprehensive system, through which patients’ range of needs for support and care can be explored. A tool should enable health care professionals to understand the specific needs patients would like to be met by professional care, following use at clearly defined points in the patient pathway. In addition to assisting professionals to determine appropriate care for a patient, the information arising from assessment might be used for a number of additional purposes, including audit and service planning.

Background

The current drive to improve the process of patient assessment stems from the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) Guidance on Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer2. This addressed the nature of the care that should be provided to help patients and their families to cope with both cancer and its treatment throughout their experience of the disease, covering a wide range of

services. It identified four distinct barriers to the provision of services for patients and carers. Needs may not be met because they are not recognised either by healthcare professionals or by patients themselves. The relevant services may not be available, because they had not been planned for or funded, or they may exist but not be

accessed because the key professionals are unaware of them. Finally, the relevant services may fail to bring maximum benefit, because of poor communication and co-ordination. The Guidance argued that there was a need for improved assessment of patient need, coordination across networks and training and support, as well as enhanced provision of services.

Although evidence suggests that patients want health care professionals to ask about their physical and emotional needs, current assessment often takes place in an

unsystematic manner and professionals frequently do not capture accurately what patients are trying to tell them3. The finding that some patients and families are

unsatisfied with the care received and feel that they are not getting what they need 4, 5, 6 may, in part, be related to inadequate assessment. Healthcare professionals vary widely in their ability to elicit relevant information7, 8 and, equally, patients vary in their ability to voice their concerns and anxieties. This can be due to beliefs that certain problems are inevitable with cancer or that clinicians do not wish to address them. Whatever the cause, needs can be poorly documented and result in unnecessary distress.

A careful assessment of patients’ needs, then, is central to the whole process of providing care. The Guidance argued that rigorous and systematic assessment should be the critical first step in supportive care, leading to the acquisition – and, in some cases, development – of appropriate services. Such assessment should be an ongoing process, with particular attention at key points, such as at the time of

diagnosis, start of treatment, completion of the primary treatment plan, when

incurability is recognised and when dying is diagnosed. In addition, an assessment should be offered at any other time requested by a patient. Yet every effort should be made to avoid unnecessary repeated assessments, with different professionals

collecting the same information. It was suggested that teams should develop a

common approach to assessment, examining the potential both for common tools and for systems to ensure that their results are shared across and between teams. The Guidance proposed that there should be a national steer on the development of approaches or tools for assessment in routine practice.

There has been some pressure to develop a national tool to create a common

approach across networks. This stems partly from networks themselves. Within the network action plan for the implementation of the NICE Guidance, they are required to provide a date by which policy will be in place, as well as an implementation date for a unified approach to assessing and recording patients’ needs. The CAT received requests for a national tool for assessment to be developed, reflecting a single assessment process. Further endorsement for the development of a national tool came from a recent report from the National Audit Office, Tackling Cancer: Improving the Patient Journey5. This recommended that the CAT should develop a

standardised approach to the assessment of patients’ physical, psychological, social and spiritual needs for use by all health professionals caring for people with cancer. In early 2005, the CAT, in conjunction with the DH, commissioned this review to inform the development of a national assessment tool. This included a review of the

literature on existing tools, a survey of networks to obtain information on current practice and discussions with those active in developing and managing the Single Assessment Process for the Elderly (a central aspect of the National Service Framework for Older People) to gain insights from that work. This work began in February and took six months. In addition, a workshop was held in Manchester in March as part of the national support and development programme for cancer

networks, in which many key issues were explored and some feedback obtained from networks.

It should be added here that this work takes place in the context of other related national work streams. Most significantly, the DH has commissioned United Health Europe (UHE) to manage the Integrated Cancer Care Programme (ICCP), currently being piloted at nine sites. Concerned to improve patient experience along the care pathway, the UHE program uses its own assessment tool, adapted from a tool initially developed for older people. The tool has been redesigned with a core to capture key components for ICCP, allowing site-specific modification to integrate with existing local practice. The tool is currently completed in paper form, with interventions and tracking supported by an electronic system. The assessment is interview-driven, with an interview guide covering all domains. Where indicated, interview results are

supplemented with findings from focused physical examinations. A key worker carries out the interview and may be supported by a care tracker under their direction. All participating staff receive training and mentoring in the use of the tool. It will be important to assess learning from this particular approach to assessment being rolled out across a number of primary care trusts.

The End of Life Care Initiative, although aimed at general palliative care (not

specifically cancer) may have some interest in assessment tools as well as training for assessment. Both the Gold Standards Framework [http://www.macmillan.org.uk/ healthprofessionals/disppage.asp?id=2062] and the Liverpool Care of the Dying Pathway [http://www.lcp-mariecurie.org.uk/] incorporate elements of assessment and have developed a number of tools. Skills for Health are currently developing

Advanced Communications Skills Training Programme for senior cancer professionals also has relevance. Finally, quality measures are currently being developed for

supportive and palliative care, based on the NICE Guidance, including measures on assessment of patient needs. These will need to be revised in the light of any approach or tool developed.

An even broader context can be seen in the recently published NHS and Social Care Model for Long Term Conditions9, setting out plans for a care management approach for the delivery of care, including a new Community Matron role. The National Service Framework (NSF) for Long-Term Conditions10 introduces new management

arrangements for transforming service delivery for people living with long-term

conditions; a central plank is that people with long-term neurological conditions should be offered integrated assessment and planning of their health and social needs. The Single Assessment Process advocated as part of the NSF for older people11 has undergone full-scale implementation. Whilst this report concerns itself with

assessment within the context of cancer care, it seems prudent to consider any future developments in the light of activity, now or in the future, in these other areas.

Methods

This study entailed three distinct methods, set out in full in Annex 1. It may be useful to provide a brief overview here.

The literature review comprised a rapid appraisal to identify currently available tools for patient assessment in cancer care, together with papers discussing the appraisal process. It focused on tools for the systematic assessment of an individual patient’s needs for help, care or support, to be used for clinical – not for research or other – purposes. Tools focused on a single domain of care, such as psychosocial needs, were excluded, as were studies of patient satisfaction. A wide list of search terms was used, with references stored and managed using bibliographic software. In all, 1803 papers were identified from the initial search, with 91 papers found to be relevant; although 36 tools were identified, only 15 tools were found to fit our criteria and are discussed here. These were appraised for their validity, reliability, responsiveness to change and feasibility, including acceptability to patients. The review was undertaken as systematically as time allowed, but was never intended to be fully comprehensive. The scoping exercise involved a two-part email survey of the 34 cancer networks in England. The Network Nurse Director of each cancer network was sent two

questionnaires in electronic format, together with a covering letter. The first questionnaire asked about the Network’s position on the development of a unified approach to assessment and about any assessment tools or approaches being considered for adoption across the network or considered particularly useful. The second asked specific questions about the nature of tools or approaches being used. Of the 34 cancer networks included in the survey, 27 responded, representing a response rate of 79%. Non-responding networks were followed up on two occasions.

Of the responding networks, 18 (67%) identified at least one assessment tool or

approach; in total, 40 questionnaires were returned detailing network assessments. In many cases, areas within networks were using a mixture of ‘off the shelf’ tools with additional assessments or questions developed locally to make the assessment more comprehensive or to meet local need. Details about the nature, scope and

administration of these assessments are reported. We were able to identify a total of 34 specific tools or approaches being used as part of the assessments. Of the identified tools or approaches, 20 (59%) were ‘off the shelf’ assessment tools and 14 (41%) had been developed by the network.

The consultations concerning the Single Assessment Process for older people entailed identifying 37 potential informants via contacts within the DH, the Centre for Policy on Ageing (CPA) website, source documents and literature. These informants were initially contacted by e-mail or telephone with an invitation to participate, with the option to provide information via a telephone interview or an electronic self-completion questionnaire. A total of 17 (46%) people agreed to participate. Of these, three had been involved in the development of the SAP, for example through membership of the ‘Assessment Task Group’ of the National Service Framework for Older People. The remaining 14 were involved in the implementation of the SAP; they provided a good cross-section of the professional constituencies involved, including SAP project managers, clinical development managers, service managers, older peoples’ network managers, and commissioning managers from social services directorates, local councils, NHS acute trusts, and NHS primary care trusts.

2. THE

LITERATURE

REVIEW

The Tools

The tools that fulfilled our inclusion criteria were as follows:

• Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System (CARES)12, 13 (previously Care Inventory of Problem Situations [CIPS]14)

• Cancer Care Monitor (CCM)15

• Creating Better Health Outcomes by Improving Communication about Patients’ Experiences assessment (CHOICEs)16, 17 18

• Concerns Checklist 19-22 (Originally developed by Devlen in 1984)23 • Distress Management Tool24

• Initial Health Assessment Form (IHA)25

• Needs Evaluation Questionnaire (NEQ)26, 27 28

• Needs at the End-of-Life Screening Tool (NEST)29 30, 31 • Oncology Clinic Patient Checklist (OCPC)32

• Patient Needs Assessment Tool (PNAT)33

• Problems and Needs in Palliative Care Instrument (PNPC) 34, 35, 36 • Problems Checklist37, 38

• Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS) 39, 40 (previously Cancer Patients Needs Questionnaire [CPNQ41 or CNQ])

• Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral to Care (SPARC)42,43 44 • Symptoms and Concerns Checklist45, 46 47

Table 1 summarises the evaluation of the tools located as a result of the searches. During the course of the review, tool developers were contacted to ascertain further details of tool development and key references. As part of this process, developers were also asked if the tool might be reproduced in this report. Annexe 2 contains brief details of each tool, in order that others might easily access these tools. Where

permission was obtained, the relevant tool has been reproduced; regrettably, we were unable to secure contact with every tool developer in the time available.

Table 1. Summary of tool properties

Content validity Construct validity Internal consistency Reproducibility

CARES - Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System 13 (Previously CIPS - Care Inventory of Problem Situations) To measure rehabilitation needs and quality of life, and find how cancer affects psychosocial, physical & behavioural states - in patients with cancer 139 items; 6 domains: • Physical (26) • Psychosocial (44) • Medical interaction (11) • Marital (18) • Sexual (8) • Miscellaneous (32) 5-point scales (0-4); "Does not apply" to "Applies very much". Plus "do you want help?" (Yes/No) option

• Literature • Interviews with patients and family members • Expert review

High correlation with interview (trained interviewer). Construct validity with: • The Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90) • Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) • Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) • Visual Analogue Scales for QoL before (QoL-B) and after (QoL-A) cancer [Tested when CARES was CIPS]

Domains: Ranged from

α = 0.87 - 0.94

Time: Soon-after first test; r = 091 (domains: r = 0.84 - 0.95, 87% agreement) Time: 1 week (results "excellent")

Reported in breast cancer patients. Physical and psychosocial change recorded over time (In SF). Correlated with FLIC at 1, 7 and 14 moths post-diagnosis (SF)

Time: 20 minutes Reading level: Unknown Acceptability: Translation available - Spanish (for Hispanic patients), short version available (CARES-SF), and version available for AIDS patients (HOPES) Made for: Care and research. Short form available suited to repeated application in clinical trials CCM - Cancer Care Monitor15 To screen high frequency cancer-related symptoms and assess overall symptom severity and QoL - in patients with cancer

38 items; 6 domains: • General physical symptoms (11) • Treatment side effects (8) • Acute distress (4) • Despair (7) • Impaired ambulation (4) • Impaired performance (4) [Plus one global QoL index]

11-point Likert scales (0-10); "Not a problem" to "As bad as possible" • Literature • Physician judgements • Review by professionals and patients

Demonstrated convergent and divergent validity through comparison with: • The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) • The Medical Outcomes Study SF-36 Health Survey (SF-36) • The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) • The Life Satisfaction Index-Short Form (LSI) • The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) • Factor analysis

Domains: Ranged from

α = 0.80 - 0.89

Time: Between 1 and 7 days apart (correlations ranged from r = 0.90 to 0.74) Time: Between 8 and 14 days apart (correlations ranged from r = 0.87 to 0.74) To be addressed in forthcoming studies Time: 20 minutes to complete paper version. 12 minutes to complete electronic version Reading level: 85% completed high school or greater education Acceptability: patients expressed a strong preference for the electronic form (versus the paper form) Made for: screening in a clinical setting CHOICEs assessment - Creating better Health Outcomes by Improving Communication about patients’ Experiences 16 To assess patients’ symptoms, functional problems, and preferences - completed by outpatient cancer patients prior to consultation

112 items (symptoms and problems); 6 domains: • Cancer specific symptoms • Functional problems • Physical • Psychosocial • Emotional • Spiritual Plus 2 global ratings: Health & QoL [Instrument not made available by developer] (Yes/No) option. Degree of severity and bother of symptoms. Analogue scales (0-10) rating "Importance" of problems as priorities for treatment/care • Literature • Review by an expert focus group specialists in cancer care • Review by patients

To be addressed in forthcoming studies - ongoing study on convergent and discriminant validity and plans to carry out further work

"Ease of Use":

α = 0.98 "Satisfaction":

α = 0.86

Tool currently being evaluated

- Time: 9 minutes (median) (SD, 10.35; range, 0.5 to 49 minutes) 25% percent of the sample used ?5 minutes. Reading level: unknown Aceptability:(a) Ease of use: 80% without assistance, 20% some assistance (weak, disability, convenience). Positive overall 'Ease of Use' score = 5.06 (range -16 to +-16) (b) Satisfaction: Scores positively skewed in both groups Made for: care. To support clinicians during consultations Instrument Purpose and

population Items and domains Question format

Validity Reliability

Table 1 continued

Content validity Construct validity Internal consistency Reproducibility

Concerns Checklist

24

To elicit and register main concerns of patient -various groups and hospice patients

Refined version = 12 items Original source = 53 items 3 domains •Illness (7) •Practical (2) •Psychological (3) 2 Forms (of refined version): • Self completion: 5-point scale (Not a worry-Extremely worried) • Interview schedule (Open questions) • Literature • Retrospective study data • Pilot work • Review by patients

Factor analysis - 3 factor solution

- - - Time: Unknown Reading level: Unknown Acceptability: Unknown Made for: To alert clinicians to nature and number of concerns. has been used to assess the effect of communication skills training and nurses' skills in eliciting concerns

Distress Management Tool

26

Screening tool for rapid assessment - in cancer patients 36 items; 5 domains: • Practical problems (5) • Family problems (2) • Emotional problems (6) • Spiritual/religious concerns (1) • Physical problems (21) • Plus 1 general distress item

One rating scale (distress thermometre) (0-10) "Extreme distress" to "No distress". Plus 33 statements (Yes/No) • Literature • Expert review - NCCN panel - - - - Time: Unknown Reading level: Unknown Acceptability: Unknown Made for: the clinical setting

IHA - Initial Health Assessment Form 27 To aid clinicians in recognition and documentation of supportive care needs - of patients with newly diagnosed cancer during their first visit to a comprehensive cancer centre

Unclear. Common supportive care needs in 7 domains: • Physical • Psychological • Practical • Financial concerns • Informational needs • Other special needs • Important personal resources Checklist. Prompts (facilitating discussion). Plus space for management plan • Literature • Patient survey of supportive care needs • Pilot test

- - - - Time: Unknown Reading level: Unknown Acceptability: Focus groups with professionals determined effective form of instrument. Introduced in practice and evaluated Made for: use as a multidisciplinary tool in the clinical setting. Used mostly by nurses NEQ - Needs Evaluation Questionnaire 28 Assessment of informative, psychological and social needs - of hospitalised cancer patients 23 items; 4 domains: • Information regarding diagnosis / prognosis (2) • Information regarding examination / treatment (2) • Communication (4) • Relational (3) Plus 12 additonal items

Statements (Yes/No)

• Interviews with patients Factor analysis on the scale only partially confirms the hypothesised structure. Later study demonstrated good fit

Domains: Ranged from

α = 0.63 - 0.76

Time: 1 week (Cohen's kappa ranged from 0.54 - 0.94) Being further developed and tested 2 items removed; originally 25 - to improve reliability

- Time: 5 minutes Reading level: Unknown Acceptability: 63% of patients OK; 24% incomplete; 3% missing values. Only available in Italian Made for: Use as an aid in clinical encounters Validity Reliability

Responsiveness Feasibility Instrument Purpose and population Items and domains Question format

Table 1 continued

Content validity Construct validity Internal consistency Reproducibility

NEST - Needs at the End-of-Life Screening Tool 33 Developed as a framework that is based on patients' experiences and perspectives regarding their care - to measure subjective experiences of patients at end-of-life 13 items; 10 dimensions: • Financial burden (1) • Access to care (1) • Social connectedness (1) • Caregiving needs (1) • Psychological distress (2) • Spirituality / religiousness (1) • Personal acceptance (1) • Sense of purpose (1) • Patient-clinician relationship (1) • Clinician communication (1) Plus 2 additional items

5-point Likert scale (strong agreement-strong disagreement) or discrete responses • Literature • Interviews • Focus Groups • Symptom items from other scales • Pilot work • Expert review - Domains: Baseline - ranged from α = 0.63 - 0.85 Follow up - ranged from α = 0.64 - 0.89 - - Time: Unknown Reading level: Unknown Acceptability: 69.2% patients found interview helpful. Equally reliable Short Form has 13 items Made for: Use as screening tool for the clinical setting, and possibly assess impact of interventions OCPC - Oncology Clinic Patient Checklist 34 To systematically assess problems related to cancer and its treatment - in adult patients in outpatients clinics 86 Items; 15 domains: • Information (12) • Fatigue (3) • Pain (3) • Nutrition (7) • Speech and language (4) • Respiration (3) • Bowel and bladder (9) • Transportation (2) • Mobility (5) • Self and home care (8) • Vocational and educational (5) • Interests and activities (6) • Emotional (7) • Family (5) • Interpersonal relationships (4) Plus 3 open-ended questions

Checklist for each item - to indicate prevalence of problem. Plus 3 open-ended questions

• Data from previous research • Based on items from other tool

- - - - Time: Unknown Reading level: Unknown Acceptability: Checklist was accepted for practical use - process evaluation by staff (100% response rate) and patients (78%) (after 4 months); positive response from nursing staff. Usefulness 82% (pilot work. n = 11 patients) Made for: Use in care

PNAT - Patient needs assessment tool 35

A tool to screen for potential problems in physical & psychological functioning - in cancer patients 16 items; 3 domains: • Physical (6) • Psychological (5) • Social (5) Overall discomfort (symptom distress) also measured

Five-item scale (no impairment - severe impairment) for each item, within context of stuctured interview • Literature • Clinical experience • Review by multi-professional group

Physical domain correlates with: • KPS Psychological domain correlates with: • Global Adjustment to Illness Scale (GAIS) • Memorial Pain Assessment Scale (MPAC) • Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) • BSI Social domain correlates with: •Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL)

Domains: Ranged from 0.85 - 0.94 Interrater reliability: Concordance co-efficient: 0.87 for physical, 0.76 for psychological, and 0.73 for social; Spearman rank order correlation coefficient: 0.59 - 0.98

- Time: 20-30 minutes Reading level: Unknown Acceptability: Item selection reviewed and rated by nurses, physicians, psychologists, and social work members of Service Made for: clinical practice; by oncology nurses and physicians (because it is the clinician who initially triages a patient's care), and social workers Validity Reliability

Responsiveness Feasibility Instrument Purpose and

Table 1 continued

Content validity Construct validity Internal consistency Reproducibility

PNPC - Problems and Needs in Palliative Care Instrument 38 A checklist of problems patients experience in palliative care, and their needs for care. To support provision of care tailored to specific demands of individual patients with advanced cancer 138 items; 13 domains: • Activities of daily living (7) • Physical symptoms (18) • Role activities (4) • Financial and administrative issues (5) • Social issues (15) • Psychological issues (15) • Spiritual issues (5) • Autonomy (9) • Informational needs (9) • Problems in consultations (3) • Overriding problems in quality of care (9) • Concerning the GP (20) • Concerning the specialist (19)

• Experienced problems: 3 options (Yes - Somewhat - No) • Needs for care: 3 options("Yes, more" - "As much as now" - "No")

• Literature • Interviews with patients and their partners • Interviews with professionals • Pilot work • Item content analysis of existing tools

Convergent validity demonstrated by comparison with two HRQL measures: • The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) • The COOP-WONCA quality-of-life measure

Domains: Problem aspect - ranged from

α = 0.67 - 0.89 Need for care aspect -ranged from

α = 0.73 - 0.92

- Acknowledged that further studies needed to develop and test

Time: Unknown Reading level: Unknown Acceptability: Original tool in Dutch. Has been translated to English (further validation required). Appropriateness and comprehensiveness also assessed Made for: Use as a patient-centred tool in clinical practice. Can be used for research Problems Checklist 39 Developed to assess the prevalence and severity of psychosocial problems experienced by the cancer patients 16 items; 4 domains: • Daily living (4) • Relationships (5) • Economics (2) • Emotions (3) Plus 2 other Four-point scale (0 = no difficulty - 3 = severe difficulty). An additional category of '5 = does not apply to me’ was included in the rating

• Literature • Audit data • Research study (n = 505)

Factor analysis endoresed the 4 factor stucture (accounting for 64% of varaiance) with the componenets on Economics and Emotions being particularly credible

Domains: Ranged from

α = 0.70 - 0.82

- - Time: Unknown Reading level: Unknown Acceptability: Patients found it quick and easy to complete Made for: Use to identify / highlight problems not usually picked up in routine practice

SCNS-Long form (LF59) & Short form (SF-34)- Supportive care needs survey

42 (Previously Cancer Patients Needs Questionnaire (CPNQ or CNQ) Developed to assess perceived needs - of patients with cancer. Plus a supplementary modules

59 items; 6 domains: • Psychological (22) • Health system and information (15) • Physical and daily living (7) • Patient care and support (8) • Sexuality (3) • Additional (4) Selection; "Applicable" or "Satisfied". Then 3-point "Need" scale (3-5); "Low need" to "High need" • Review of CNQ tool by oncology specialists and patients • Pilot work

• Factor analysis revealed 5 factors were identified which together accounted for 64% of the total variance

Domains: Ranged from:

α = 0.87-0.97

- Longitudinal study underway Time: 15-20 minutes Reading level: 11 - 13 years Acceptability: Rated by patients - was easy to understand and complete. 7-12% missing data for each question. Trial of use by touch screen in clinic demonstrated acceptability Made for: Quality assessment, research and intervention

Validity Reliability

Responsiveness Feasibility Instrument Purpose and

Table 1 continued

Content validity Construct validity Internal consistency Reproducibility

SPARC - Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral to Care 45

Developed to assess the distress caused by advanced illness, and to screen symptoms and problems to guide referrals to specialist and palliative care - For patients with advanced illness 45 items; 7 domains: • Communication and information (1) • Physical symptoms (21) • Psychological issues (9) • Religious and spiritual issues (2) • Independence and activity (3) • Family and social issues (4) • Treatment issues (5) • Items: Help / information / contact with professionals (Yes/No) • Remaining Items: 4-point rating scale (0-3); "Not at all" to "Very much" • Literature • Interviews with patients and professionals • Cognitive interviewing • Consultation with experts • Pilot work

- Inter-item correlations examined, and item-total correlation

- - Time: 45 minutes (median). Range of 15 to 105 minutes Reading level: Unknown Acceptability: Assessed during iterative process of development Made for: Professionals as a screening measure, to aid their referral decisions. Future version planned to allow patients and carers to use self-rated measure to support need for Specialist Palliative Care Symptoms and Concerns Checklist 50 To determine prevalence and severity of symptoms and concerns in routine practice as adjuvant to clinical assessment - of patients with advanced cancer 32 items (29-32 items); 4 domains: • Physical symptoms (11) • Cognitive / psychological (4) • Other concerns (14) • Patient defined (3) Rating scale - 'how much of a problem' (0-3); "not at all" to "very much" • Literature • Expert panel • Pilot work • Patient interviews Generally demonstrated convergent validity when compared with: • Symptom Distress Scale (SDS) • Palliative care Outcome Scale (POS) - Patient version

Overall: α = 0.85 Time: Over 2 consecutive days - weighted Kappa 0.35-0.77 Able to discriminate between different groups of patients (e.g. Outpatients vs. hospital inpatients)

Time: 5 minutes Reading level: Unknown Acceptability: 97% felt comprehensive, 82% felt easy to complete, 79% good idea, 98% participated, 97% completed all items Made for: Clinical use. Also for audit and research Validity Reliability

Responsiveness Feasibility Instrument Purpose and

Purpose and population

Table 1 shows the many different purposes for which the tools were developed. These include a focus on the health status of patients, providing information on particular symptoms or problems, personal resources and sources of support, care preferences and satisfaction with care. Often, the experience of a problem – or dissatisfaction with an element of care – is not clearly distinguished from a need for more or better care. A small number of instruments address needs for care (help or support), such as the CARES, the SCNS, the PNPC and the Distress Management Tool. Whilst developers imply that many tools may be used for screening (identifying those who might benefit from referral for more in-depth evaluation or who might warrant intervention), only three tools were specifically developed for this purpose. The CCM was designed to screen for high frequency cancer-related symptoms, side effects and current concerns at each clinic visit; the SPARC and Concerns Checklist identify palliative care needs of patients in order to guide referral of patients and families to palliative care. The CCM, the Concerns Checklist, the Symptoms and Concerns Checklist and the IHA are put forward as aids for clinicians to enable them to recognise and document supportive care needs as an adjunct to consultation. Most tools address the needs of the general population of cancer patients and have been developed with mixed groups. A few, however, were developed to address the needs of specific groups of patients, such as those with advanced cancer (PNPC, SPARC and Symptoms and Concerns Checklist) or, even more specifically, at the end of life (NEST). Most were developed for use in an outpatient clinic; the exceptions are the NEQ (designed for hospitalised cancer patients), the NEST (designed for the bed side) and the SPARC and Symptoms and Concerns Checklist (both of which can be used in a primary care setting).

Content

The content of tools was drawn from a number of sources, including existing literature, review of item content of existing tools, reliance on clinical experience of tool

developers, and in some cases research by the tool developers, such as interviews (for the NEST and CARES) or surveys (the IHA). Content was often refined (and reduced) through an iterative process, involving reference to the opinions of health care professionals and patients, pilot work and in some cases through recourse to statistical techniques, such as factor analysis (for example, for the SCNS and the NE Q).

Table 1 provides an indication of the domains covered by the tools and their relative emphasis in terms of different areas of need. The content of tools was compared using the domains of needs related to health status and needs for, and satisfaction with, health care. Tables 2 and 3 provide a more detailed examination of the content of the individual tools with respect to these domains.

Degree of coverage varied widely. The most comprehensive instruments with respect to health status (defined as covering to some degree the full range of needs related to health status) include the PNPC, OCPC, Symptoms and Concerns Checklist, SCNS and SPARC. In particular, the Distress Management Tool and SPARC covered all the dimensions in our classification related to health status. Coverage did not necessarily equate with length: some of the shortest instruments proved to have items across a number of domains. As noted above, only the CARES, SCNS and PNPC addressed the dual facets of how much a problem a particular issue presents, along with the degree to which patients wish help or attention in order to respond to this need. Broadly, symptoms and side effects, together with physical and psychological functioning, were more fully covered than were other aspects of need, such as spirituality (often purely confined to issues of religion), cognition and occupation.

Table 2. Comparison of content of assessment instruments compared by reference to needs related to health status

INSTRUMENTS

→

DOMAINS ↓

CARES† CCM CHOICEs† Concerns Checklist (Refined version) Distress Management Tool†

IHA† NEQ NEST OCPC PNAT PNPC Problems Checklist SCNS SPARC Symptoms and Concerns Checklist Symptoms and side effects 19 √ 16 √ 1 1 17 17 5 21 11 Physical functioning √ 8 √ 7 2 √ 1 1 8 4 7 2 2 3 1 Psychological well being √ 11 √ 8 √ 4 1 5 5 24 4 22 10 9 Spiritual well being √ 1 1 3 5 1 2 2 1 Cognitive 1 4 2 1 1 1 Social √ √ 3 5 √ 2 1 10 2 18 5 1 5 2 Occupational 2 2 √ 2 1 4 1 7 2 1 1 2 Global assessment 1 √ 1 1

† Unable to map accurately, as instrument not made available by tool developer. Information taken from publications

Table 3. Comparison of content of assessment instruments compared by reference to needs for and satisfaction with health care

INSTRUMENTS

→

DOMAINS ↓

CARES† CCM CHOICEs† Concerns Checklist (Refined version) Distress Management Tool†

IHA† NEQ NEST OCPC PNAT PNPC Problems

Checklist SCNS SPARC Symptoms and Concerns Checklist Participation in care and information provision √ 5 2 12 24 9 6 1 Accessibility of care 2 2 1 5 2 Flexibility of care delivery 3 4 Continuity of care 5 1 Healthcare professionals technical and interpersonal skills √ 5 1 25 1 4 5 1 Provision of equipment Waiting times 1 Environment 1 1 Privacy and dignity 1 2 Support for carers 4 2 2 Global satisfaction

† Unable to map accurately, as instrument not made available by tool developer. Information taken from publications

Both the SCNS and the PNPC possess a broader coverage of issues related to satisfaction with health care than the other tools reviewed, containing a significant number of items addressing quality of care. It is not surprising that the majority of tools did not cover this aspect in any depth, as their purpose was directed at needs with respect to health status, rather than assessing quality of care received.

Question format and scoring

Question formats reflect purpose. These include Likert-type scales (ranging from 4 to 100 point scales) that address particular aspects of need, such as the degree to which a problem is experienced, the degree of bother or the degree of importance. Checklists tend to utilise dichotomous items (Yes or No) to indicate wants for help or the presence or absence of a need. Many of the tools adopt a combination of

formats to accommodate different types of questions. The IHA does not appear to have a scoring system; it captures information about supportive care needs through clinical notes. Finally, the NEST consists of a set of questions to be used by

clinicians at the bedside to assess and screen patients and is designed so that questions unfold aligned to particular dimensions.

The majority of tools adopt some kind of scoring system, especially at the individual item and domain level (CCM, PNAT, SCNS, Problems Checklist, IHA). Most do not pursue an overall score, however the CARES, CCM and Concerns Checklist are exceptions to this.

In a few cases, tool developers adopted more sophisticated scoring algorithms that would require a computer to generate scores. For example, the CCM adopts a process whereby the raw score for each item is converted to a normalised T score. This is done in order to ensure that the same T score falls on the same percentile rank in a normal distribution, thus providing the clinician with information about the location of a particular patient within a normal distribution.

Some tool developers specifically discuss an intention to move to a system whereby the score might be used to distinguish those patients who warrant referral to different disciplines or specific services (Distress Management Tool, SPARC) or to provide a basis for targeted interventions (PNAT). Other tools, however, focus solely on revealing the presence or absence of a need that could then be examined more closely within a clinical encounter (NEQ, Symptoms and Concerns Checklist). But, on the whole, there was an absence of discussion of how the assessment results might be used to plan care, or how to facilitate clinical interpretation of individual scores for case-finding and monitoring purposes.

Finally, there was little reference to the interpretation of scores. The one exception is the PNAT, whose developers suggest caution when aggregating dimension scores in individual patients. They assert that a better knowledge is necessary of the clinical relevance of such scores and suggest that it might not be appropriate to use

aggregated scores in individuals, although they might well be best used for analysing problems and needs in groups of patients.

Validity

A wide variety of approaches were taken to ensure and examine tool validity. The extent to which validity was demonstrated also varied greatly.

For content validity, tools tend to rely heavily on existing literature; indeed, this was the most common approach (used in 10 cases). In one case (PNPC), the developer also selected items from existing tools. Panels of professionals and patients were frequently used to derive, select or review items. Pre-testing of items was

undertaken for some tools (SCNS, SPARC, Symptoms and Concerns Checklist, OCPC). The generation of items through interviews with patients was a feature of a number of tools, although the scale on which this was undertaken varied. Some authors used extensive procedures to derive items based on patients’ accounts; combined with literature reviews, review by patient and professional panels and pre and/or pilot testing procedures. The CARES and SPARC, Symptoms and Concerns Checklist, and PNPC are examples of the results of such careful procedures.

Construct validity was generally assessed by examining the relationship between the tool under development and a measure of another concept to which it was

theoretically related. On the whole, where this was examined, adequate construct validity was demonstrated. Further empirical validation of the tool beyond its initial construction by the original developers was undertaken only for the CARES and SCNS. These tools also feature successive verification by increasing numbers of researchers. A number of tool developers report plans to conduct further validation studies. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis was used at various stages of tool development in a small number of cases (SCNS, NEQ, NEST). Validity testing is absent for the distress management tool, IHA and OCPC.

Reliability

Data on the reliability of tools are shown in Table 1. Test-retest reliability was assessed in the CARES, CCM, NEQ, and Symptom Concerns Checklist. For some other tools, only internal consistency was demonstrated, mostly through computing Cronbach’s alpha. The majority fall well short of the recommended reliability

standards for individual patient application, which ranges from a low of 0.90 to a high of 0.95, the desired standard48. Internal consistency was also examined through resorting to Cohen’s kappa, a coefficient of agreement. Kappa has a value of 0 if agreement is perfect. Conventionally, values of kappa lower than 0.4 indicate poor reliability, from 0.4-0.6 moderate, from 0.6-0.8 substantial and from 0.8 – 1 almost perfect reliability49. This was undertaken for the NEQ and demonstrated that this tool had substantial reliability.

For scales designed for use by health care professionals, some investigators assessed inter-rater reliability (consistency of a measure when administered by different interviewers), through employing a coefficient of concordance, as was the case for the PNAT. The PNAT achieved moderate to strong concordance.

No data on reliability are available for the Concerns Checklist, Distress Management Tool, IHA or OCPC.

Responsiveness

Responsiveness (or sensitivity to change) has rarely been addressed. One

exception is the CARES-SF; a study following up patients one, seven and 13 months after surgery demonstrated its responsiveness to actual changes occurring over time50. Improvements in scores were demonstrated as time from surgery lengthened. Evidence was obtained to show that two instruments were able to discriminate

between different groups of patients, for example at different phases of illness (CARES) or different groups of patients (Symptoms and Concerns Checklist). Feasibility

Practical concerns are an important consideration in a clinical setting, affecting both the patients and professionals involved in the assessment process, especially as time is necessarily limited. Yet only limited data were found on feasibility. Wide ranges of completion times were recorded, ranging from 5 to 45 minutes. Electronic versions of assessment tools appear to have shorter completion times and there is some evidence that patients, if given the choice, prefer an electronic format (for example the CCM). Tools employ varying methods of administration, including both paper and pencil format and electronic solutions; some offer a choice on this issue. Moreover, some require self-completion by the patient, whereas others require an interview with a professional (two tools offer both options). See Table 4 and 5 for an analysis of the tools in terms of their method of administration and completion.

Table 4. Method of tool administration

Form: Paper form Touch-screen computer Pen-based computer Tools: CARES SPARC Concerns Checklist

Distress Management Tool IHA NEQ NEST OCPC PNAT PNPC Problems Checklist SCNS

Symptoms and Concerns Checklist

CCM

CHOICEs SCNS

Table 5. Method of tool completion

Method: Patient

self-completion or professional Patient completion Professional completion Tools: CARES CCM Distress Management Tool OCPC PNPC Problems Checklist Symptoms and Concerns Checklist CHOICEs NEQ NEST SCNS Concerns Checklist IHA PNAT SPARC

Of the professionally administered tools, only the developers of the PNAT and IHA had considered training issues. In the case of the PNAT, the question was explored of whether training in its use would enhance the degree of agreement between raters (including physicians, nurses and social workers), but it was found that the scores of the trained group did not differ significantly from the untrained group. Similarly, there was no difference between scores produced by physicians and nurses. In the

account of the IHA’s development, mention was made of training oncologists and nurses in its use, with further training provided for nurses on interviewing and assessment. Prompts were provided with this tool to facilitate discussion around personal and social issues.

The level of support required for people to complete a tool could be an important factor in determining the feasibility of a tool in practice. Only a few papers referred to this dimension. In those involving self-completion by patients, some mention was made of having help available for the CHOICES tool (computer-based) and the touch screen version of the SCNS.

Acceptability to the target group is clearly a prime consideration and there have been some attempts, albeit involving variable degrees of rigour, to collect information on the content, process and outcome of using a tool from the viewpoint of patients or health care professionals. Appraisals have been made, for example, of ease of use (CHOICES), degree of missing data (NEQ), and degree of patient satisfaction with the tool (CHOICES). During preliminary stages of development, information is often collected from patients on aspects such as format, completeness, and clarity. The suitability of tools for diverse populations has not been well explored; only a few developers have examined the reading level of their tool and still fewer have sought to develop versions in different languages. Some general comments on acceptability of these tools are provided in the concluding section of this report.

Summary of tool evaluation

The searches identified 15 tools for the assessment of patients’ needs. Most had been carefully constructed, but lacked generalisability across the cancer trajectory and most focused on one particular context for care (such as outpatients) or point in the cancer pathway. A few had been developed without recourse to patient input and thus are prone to assess needs seen to be important from a professional

perspective. All have very different organising structures, and few cover all the dimensions of care, failing to offer a comprehensive approach to assessment. Some topics generally regarded as important in cancer and palliative care, such as

spirituality, were often missing. Few discriminated between the assessment of health problems and the desire to receive care, resulting in ambiguity about whether or not a patient wanted help. This left clinicians needing to interpret the practical

consequences of information gathered as result of completing the assessment of the tool, and does not address ‘desire’ for support for care even when a need is

identified. Most tools employed a self-report format, and a number of computerised-assisted systems of assessment have been developed.

Validity and reliability have been addressed to varying degrees, some thoroughly, others not at all. It is disappointing that very few tools had been tested over time for their responsiveness to change. Without this information, it is not possible to

understand how the tools might perform over time and whether they are able to capture how effective a care intervention might be in addressing a particular need. Feasibility may be a critical factor determining the clinical possibilities of these tools, yet information on their feasibility for use in routine care was very scarce.

Whilst some of the tools appear to have considerable merit, there is nothing to suggest that one is more fit for purpose than another. The lack of testing for use in practical care is a severe limitation of the all the tools reviewed, although some of the developers of newer additions to the literature, such as the SPARC and PNPC, have plans to undertake such work in the near future. This leaves many questions

unanswered on how a particular tool might support patient management in the ‘real’ world of cancer care.

The Impact of Assessment Tools

During the course of reviewing the literature on the development and application of specific tools, some efforts to address the impact of such tools on practice were noted. This topic was not part of the initial scope for the review and hence our discussion here is neither exhaustive nor systematic. Nonetheless, as the principal function of tools is to improve clinicians’ understanding of patients’ needs and

therefore their ability to respond them, the impact of such tools on clinical practice is a central issue to any debate on assessment.

Surprisingly little research attention has been given to this issue. One review paper, however, pulled together evidence from 13 randomised controlled trials in the broad context of patient care, i.e. not specific to cancer51. The findings were quite diverse; in general, there was evidence that assessment tools improved the detection of psychological problems and, to a lesser extent, functional ones, but there was

relatively little impact on the subsequent management of patients. Only two studies found higher referral rates to other professionals compared to a control group and only two showed more changes in patients’ treatment. Conflicting results were found in relation to the impact on doctor-patient communication. Moreover, there was little evidence for any impact of such systems on outcomes in patient care or on patient satisfaction.

The review suggests that the impact of such measures on routine practice is likely to depend on the extent to which the information is seen to be clinically relevant. One study stressed that positive findings from one instrument were due to its specificity to a particular condition (in this case, depression) and that generic measures may not have the same impact. It is also argued that the use of this information will vary with the nature of patients’ problems, for instance their severity, although evidence on this issue varied. Some authors also suggested that nurses, compared to doctors, might make more use of the information. Few of the reviewed studies investigated the impact of a tool on doctor-patient communication and none addressed its impact on patient involvement in decision-making.

This issue has been addressed in more recent research in the specific context of cancer, with mixed results. In a study where 450 people with cancer were given a needs assessment, but the information was passed on to the health care team for only a proportion, no significant differences in needs or psychosocial functioning were found at a follow-up assessment, nor in satisfaction with care; there was,

however, a significant reduction in depression for the intervention group, compared to the others52. In contrast, another research team found that there was greater

congruence between patients’ reported symptoms and preferences and those discussed in the subsequent consultation where a tool was used, compared to a control group16. A paper on a very patient-centred assessment system (not a tool but ‘an opportunity for patients to tell their story’) at a complementary health centre found a large majority of patients reported improvement in their principal concern, but changes in mental and physical well-being were limited53. One early study found a significant change in the control of pain and other symptoms among palliative care patients in hospital following the use of a single domain assessment tool, together with a significant change in the ‘insight’ of patients and carers regarding their

situation54. Another found that the use of an assessment tool by nurses seemed to forestall increasing symptom distress among patients with lung cancer over time, compared to a control group55.

A recent paper addressed changes in the quality of life of cancer patients following the completion of an assessment tool56. The intervention was found to increase discussion of chronic symptoms and had a significant impact on patients’ well-being, compared to two control groups. There was, however, no discernable impact on patient management, i.e. medical decisions were not changed. The authors question whether involving doctors in this study sensitised them to issues for discussion, such as patients’ emotional problems, thereby affecting the results from their consultations with patients in the control group. Another paper by one of the authors57 argues for more research to understand the impact of assessments on the process of care. The review paper noted above51 also explored findings on barriers to the use of assessment tools. It proposed that attitudinal barriers might be expected, i.e. doctors would be hostile to their use. Potential problems cited included scepticism about the validity of measures, a preference for more informal methods of obtaining the

information, fear of compromising patient confidentiality and concern that the data might be used to compare doctors’ performance. In fact, most papers (covering 13 studies where measures were actually used in routine practice) found positive attitudes among doctors to the feasibility, acceptability and utility of using such measures. The review paper also noted several papers that identified practical barriers, such as a general lack of time and money for the collection, analysis and use of the data. Lack of information technology support (IT) could also be an issue. Some potential methodological barriers were noted, involving the psychometric properties of tools, such as their responsiveness to change, discussed above. More research to further understanding of the impact of assessment on the process of care is needed, together with research on health professionals’ responses to the use of assessment systems. Early research suggests that they appear to improve doctor patient communication, but their impact on patient outcomes is less clear56.

3. THE SCOPING EXERCISE

The following information is based on the 27 (out of 34) cancer networks responding to our survey. Of these, 18 (67%) identified at least one assessment tool or

approach, returning 40 questionnaires identifying assessment tools or approaches used in their area. These involved a total of 34 different assessment tools or approaches, of which 20 (59%) were ‘off the shelf’ tools and 14 (41%) had been developed by the Network itself.

Cancer Networks’ Response To Developing A Unified Approach: An Overview

A small proportion (15%; N=4) of cancer networks reported that they had both established a network-wide working group for this area and taken some action to review current practice and develop a unified approach to patient needs assessment. Examples of actions taken include:

• Agreeing a network unified approach to patient needs assessment;

• Developing guidelines;

• Identifying validated ‘off the shelf tools’ to be piloted across the network;

• Mapping the assessment tools used by individual specialist palliative care services that might be rolled out across the network;

• Developing and piloting a network wide assessment checklist to ensure that all specialist nurses are assessing the same areas of potential need.

• Looking at how assessment can link with the Single Assessment Process across primary care trusts and social services;

A further group of networks (30%; N=8) reported having identified a lead or project group to take forward the agenda of patient needs assessment but having made minimal progress to date. Examples of project groups include:

• Sub-groups working on T10 action plan topics which include developing assessment packages;

• Sub-groups set up across a network to examine the assessment tools currently being used, identify a network wide approach, develop supporting education and a roll-out programme;

• Work undertaken by a number of the work streams taking forward the NICE Supportive and Palliative Care Guidance.

Over half the cancer networks (55%; N=15) reported having taken little or no action towards the development of a unified approach to assessment. Many noted that they were waiting for national guidance on this issue.

Figure 1. Stage in the development of a unified approach

15 8

4

Little or no action Started but minimal progress

A developed unified approach

The development of policy and guidance on patient needs assessment

Only two cancer networks reported having established guidance on patient needs assessment, with an additional five reporting that they were in the process of developing some guidance. Specific details of the content of policy and guidance were not collected in this exercise. Just over half of the networks (52%; N=14) reported that they had no guidance, or guidance only in individual areas or organisations across the network (22%; N=6).

Figure 2. Policy and guidance

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 No guidance Guidance in individual areas Developing network guidance Established network guidance Number of Networks

Network leadership on patient needs assessment

Overall, a reasonable proportion of cancer networks (45%; N=12) could identify a lead or project group who were responsible for taking forward the development of a unified approach to patient needs assessment; the majority (55%; N=15), however, reported that they had not yet identified a lead.

Leads and project groups consisted of professionals from a range of fields. Some networks (42%; N=5) reported that they had established multi-disciplinary groups to take this area forward. In other networks, the Network Nurse Director (N=2) or Palliative Care Group (N=3) were reported to be leading the work.

Figure 3. The identified lead

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mult iprofe ssional group Palliative c are group Networ k Nur se Dir ector Supportive Car e Gr oup Primar y car e group Number of Networks

Areas currently being explored by lead or project groups included:

• Developing network-wide guidelines for patient assessment and exploring how such guidelines can link with specialist referral guidelines;

• Identifying validated tools and locally developed tools that are available, and looking at whether they are easy to administer in the clinical setting and acceptable to health professionals, patients and carers;

• Identifying key points in the care pathway for assessment;

• Development of a local proforma to ensure holistic needs assessment takes place;

• Exploring how needs assessment can link into the Single Assessment Process (SAP), and whether SAP assessments would be appropriate for patients under 65 years of age, or for use in cancer care

• Exploring how a unified network assessment could be integrated with existing local assessments

• Looking at compatibility of assessment with computer systems or software already in use;

• Looking at how assessment can be communicated between primary, secondary, and tertiary care;

• Identifying resource implications for introducing assessment, i.e. how to deal with implications of needs being identified;

• Identifying staff education/training needs relating to assessment;

• Identifying workforce issues related to implementing an assessment tool;

• Communication of assessment between primary secondary and tertiary care.

Engaging with key stakeholders

Almost half of the networks (48%; N=12) (all those who reported having identified a lead or project group for this area) reported having discussed the development of patient needs assessment with key stakeholders. The type of organisations engaged by the lead or project group included: social care organisations, voluntary sector organisations, service user groups, primary care and community nurses, Marie Curie Cancer Care and other charities.

Network Patient Needs Assessment: An Overview

Of the 27 responding cancer networks, 18 (67%) identified at least one assessment tool that they felt might contribute to a unified approach across their network or which they had used particularly successfully. The majority of responding networks

provided details of more than one assessment tool being used within their network. In total, networks returned 40 questionnaires detailing assessment tools used in their area. In many cases, areas within the networks were using a mixture of ‘off the shelf’ tools with additional assessment tools or questions they had developed locally to make the assessment more comprehensive or to meet local need. Details about the nature, scope and administration of these assessment tools are reported in the subsequent sections.

We were able to identify a total of 34 different specific tools or approaches being used for assessment. Of the identified tools and approaches, 20 (59%) were ‘off the shelf’ assessment tools and 14 (41%) had been developed by the network.

Specific assessment tools or approaches identified

Table 6. shows the ‘off the shelf’ assessment tools identified and the number of networks that reported using each tool.