DESIGN 2005 – The Industrial Design Technology

Programme

1

The field of design has many players

Industrial design has a growing connection to corporate image, branding, and other core business issues. Design is therefore a vital factor in gaining competitive advantage. Industrial design can also generate cost benefits in production through processibility and in use through usability. User orientation is currently a key trend in product design, while design as a broader concept also encompasses the design of objects such as art and craft products. Industrial design is not a branch of industry in the traditional sense. Rather, it is an activity and a mode of operation applicable over a wide array of branches. Despite their small number and wide range of activities, the players in the field share a common identity, which is largely based on education. The increasing significance and visibility of design is further underlined by the fact that Statistics Finland is currently devising ways to compile statistics on design-intensive business and developing uniform monitoring for the field. This report uses the term ‘design branch’, although in the traditional classification such a branch does not exist.

The key players in design can be classified as follows:

• Industrial and service companies utilising design

• Design firms

• Artisans and craftspeople

• Education and research

The group utilising design is very wide. Design plays a key role in design industries, such as the textile, clothing, leather and shoe industries, in the production of design-intensive consumer goods (such as tableware), and in the furniture industry. Design is, however, utilised in quite a number of other areas, such as in packaging. As much as one half of all industrial companies use design, with the metal industry leading the way in quantity. It seems that the use of design has slightly increased since 2002, but the number of in-house designers employed by industrial companies has remained low. 1

The website of Industrial Designers Finland lists more than 50 industrial design firms and freelancers, but most of the companies, up to 80%, are small one-man companies or employ a few people only. There are only half a dozen design firms employing more than ten people. 2The largest design firm in Finland and the Nordic countries is ED-Design Oy in Turku, which currently has a permanent staff of 36.3 Design firms are considered to have a key role in spreading scientific information, but due to their small size, performing this task is challenging.

1 Holopainen, M., Järvinen, J. (2006) Muotoilun toimialakartoitus 2006, The New Centre of Innovation in Design 2 Holopainen, M., Järvinen, J. (2006) Muotoilun toimialakartoitus 2006, The New Centre of Innovation in Design

Artisans are closely associated with the image of design, and design is an important part of their professional identity. Although they traditionally have a strong position in the design branch, the group is clearly outside the scope of this programme.

In the field of education and research, the University of Art and Design Helsinki is clearly the key player in Finland. As regards research, Designium, the New Centre of Innovation in Design, was established as a result of the same Government resolution on design policy that also formed the background to the DESIGN 2005 programme. The University of Art and Design Helsinki is large by international standards, and is also internationally recognised as a leader in education in the field. Expertise has also developed in old crafts schools and the polytechnic sector, but research in polytechnics rests mainly on the shoulders of individuals. Design is not research-intensive in the same sense as something like pharmaceutical R&D; instead, it consists of expert tasks. The connection between research and business has not been strong, although as with many other expert services, there are clear opportunities for this. In addition, the branch does not have actual research-driven business (spin-offs).4 Design is carried out both internally in the industry and externally by design firms. Design-related business means either selling expert services or selling products that have design as their key element.

2 Timing, objectives, and implementation of the programme

2.1 Conception and timing of the programme

Among public sector players, the Finnish National Fund for Research and Development (Sitra) has played a key role in putting design on the education and research agenda. The 1998 report on design, Muotoiltu etu,5 was one of the factors behind the rise of the theme. The project identified design as an untapped resource and recognised the need for business know-how and development of a critical mass in the branch.

Based on further reports on the branch, the Government issued a resolution on design policy on 15 June 20006 and launched the associated Design 2005! Programme, which have been important background factors for Tekes’ DESIGN 2005 programme. The resolution was based on the Government Programme and its objectives of strengthening the competitiveness of Finnish production. The programme gave priority to increasing expertise in design through education and research.

The resolution states that “The aim of universities, the Academy Of Finland, the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation Tekes and other sources of finance is to create a multidisciplinary research programme on design, which will connect research on design to research in other academic disciplines.” This crucial part of the resolution obliged Tekes and the Academy of Finland to take action to promote research in the design branch. Simultaneously, Tekes was also engaged in broadening its own vision to include such things as service business and business know-how, so the time was ripe for the creation of a technology programme also involving companies.

4 Kankaala, K. (2005) Kohti tutkimuslähtöisen yrityksen määritelmää, Ministry of Education publications 2005:1 5 Korvenmaa (1998) Muotoiltu etu I. Muotoilu, teollisuus ja kansainvälinen kilpailukyky : Designin tila ja

kehittämiskohteet, Sitra 1998

The Government resolution created a natural foundation for a joint programme with the Academy of Finland.

During the whole process, important opinion leaders in promoting the subject included Yrjö Sotamaa, Rector of University of Art and Design Helsinki, and, from the industry side, the Honorary Mining Counsellor Krister Ahlström in particular. The Confederation of Finnish Industry and Employers was also active in the matter (for instance, it signed a co-operation protocol on design policy with the Finnish Government on 7 December 2000).

Preparations for the DESIGN 2005 programme took place in 2001, and the programme was launched in the beginning of 2002. It realised the design policy programme from Tekes’ perspective, which is industrial design. DESIGN 2005 was the first Tekes programme directly concerned with design. Before that, design had been financed to some extent as part of product development projects. With the new programme, design research and the role of design in corporate R&D took centre stage.

During the preparation of DESIGN 2005, the Academy of Finland already expressed its interest in launching a joint programme. The Academy of Finland was also working on the design policy programme, but its research programme Industrial Design did not join the Tekes programme until later, in 2004. It will, however, continue until 2007 and aims at multidisciplinary research encompassing the entire system of industrial design and including research on engineering and technology, economics, culture, and social sciences.

An essential background factor for the activity of the design branch was the fact that this was the first time Tekes had ventures clearly focused on design, and the branch wanted to seize the opportunity of having the prestige of Tekes behind its endeavours. Similarly, the branch desired the support and prestige of the Academy of Finland for design research. Discussions on the role of those providing funding were held at the highest level.

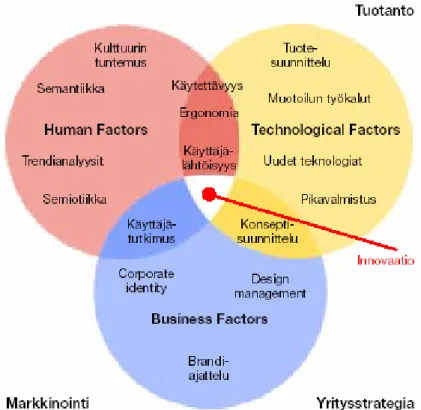

When preparation for the programme began, there was no clear view on the themes and the bigger picture of design research. A description of the research themes in industrial design (Figure 1) was used to clarify the idea. Of these themes, Tekes focused on Technology and Business Factors, and the Academy of Finland looked at Human Factors. Research themes were not, therefore, issues of basic research and subsequent applied research, but parallel and interlinked thematic fields. Several thematic areas are new to Tekes and fall beyond the scope of traditional technology-related research.

Figure 1. Thematic fields of research identified in the DESIGN 2005 programme.

2.2 Objectives of the programme and their development

The launch of the programme was backed by the view that the significance of design would be enhanced as products become more technologically advanced: the branch was seen as possessing great potential. It was estimated basic know-how and the utilisation of design competence in industry was still rather poor in Finland, apart from a few large international companies. Finnish design firms are also small and the research tradition in the branch slim. The motto for the programme was “making industrial design an important part of international competitiveness”. This meant making design an integral part of the Finnish innovation system. One of the central aims was to enhance competence in the branch. Based on these ideas, the objectives of the DESIGN 2005 programme were set down as:

• Developing the standard of research on design;

• Developing the utilisation of design in product development and business strategies;

• Developing the competence of design firms and strengthening their service operations. The idea behind these general objectives was to bring together three different groups: research bodies, design firms, and the industries utilising design. The aim was to revitalise design by both producing new, scientifically-based services, and increase demand by developing the utilisation of design expertise. The programme, furthermore, aimed at

increasing industry awareness of industrial design and, linked with this, broadcasting the results of the programme.

From the perspective of research, the key starting point was that design has traditionally been an expert service. As in many other fields of expertise, knowledge and competence have not been explicit, but have consisted of problem-solving skills gained through practical work. Therefore, the aim was to systematise and formalise this competence and understanding of the expert activities and provide generic knowledge on such matters as the possible impact of design and the practices of user-oriented design. Scientific research in design does not have a strong academic tradition. As in other branches of art, the research tradition, paradigm, and frame of reference were still in their initial stages, particularly when the programme was launched. Contacts between the various fields of research and the corporate world also provided challenges.

From the perspective of design firms, a key objective was to enhance competence and broaden the service supply towards design consulting and strategic thinking. Knowledge and methods coming from research were seen as playing a key role in this. The structure of the branch was a central challenge: the majority of design firms are small companies run by a few professionals and are, thus, not in Tekes’ primary target group.

Although one of the objectives of the programme was to improve the competence of design firms, in practice the programme focused on the development of the utilisation of industrial design, that is, the perspectives and needs of the industry. Through the companies utilising design, the group of potential appliers is very wide. The objectives thus included creating wider awareness in the industry and, through that, renewing the design branch by increasing demand. Tekes’ strict definition on industrial design has also been criticised in the design world.

One of the objectives of the programme was the promotion of international contacts in the branch. International contacts, in both research and the operations of design firms, were limited, although design expertise as such is not bound to any specific culture. It is estimated that international competition in the provision of design services will increase, and that corporate structures in the branch will simultaneously become more international. The competitive strength of Finnish design firms is crucial in this development.

Interviews conducted in connection with the programme evaluation considered the objectives current and topical, and they remain so. The programme’s timing was good, as the significance of design as a competitive factor has increased in Finland as well as internationally. There were no major changes to the programme’s objectives or implementation during the programme period. The suggestions for redirection of the programme given in the interim evaluation did not lead to any major changes.

2.3 Programme contents and implementation

The DESIGN 2005 programme was launched in the beginning of 2002, and it ran until the end of 2005. Some enterprise projects still continued into 2006. All in all, the programme

implemented 73 projects.7 In addition, the Academy of Finland research programme funded eight projects. Counting both research and enterprise projects, evaluation interviewees estimated that a total of approximately 100 companies participated in the programme.

The total volume of Tekes’ share of the programme amounted to slightly over €22 million, with the share of Tekes project funding at €10.3 million. In addition to project funding, Tekes covered costs related to programme activities, such as co-ordination, to the amount of €0.9 million. The Academy of Finland funding for research projects amounted to €2 million. The distribution of Tekes funding between enterprise and research projects and the funding share of various financial sources is given in Table X.1.

Table 1. Realised project funding in the DESIGN 2005 programme, € million.

Enterprise projects 6.1 Research projects 4.1 Tekes funding Tekes total 10.3 Enterprises 11.1 Academy of Finland 2.0

Funding by other parties

Research institutes 0

Total 23.4

Continuous application for enterprises

Enterprise projects were not subject to a separate application procedure. Instead, new projects were accepted to the programme throughout its duration. The programme had a total of 48 enterprise projects. The enterprise projects mainly involved only the largest design firms. There were eight projects led by design firms. The small size of design firms clearly restricted their participation in the programme with a project of their own, which leads to a limited impact on the development of the branch as regards the transfer of information and knowledge.

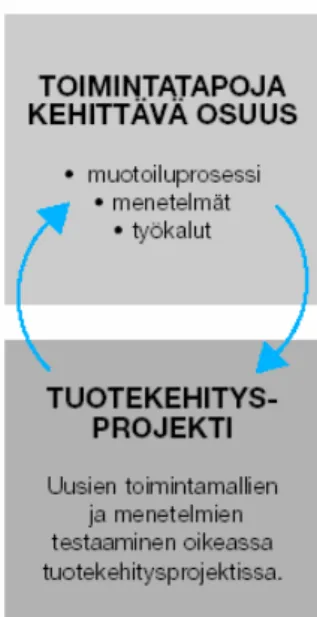

What was important in the enterprise projects was that their objective was not only to generate new products (that is, funding was not only given to projects on product design), but also to promote the integration of design competence, usability, concept design and so on in product development. In other words, the central aim was to strengthen the utilisation of design through the development of the R&D process. This aspect, aiming at developing procedures, is illustrated in Figure X.2.

Possible enterprise project types included:

• Strategic utilisation of design in companies

o Considering design at different stages of business

• Development of design resources (organisation, people, expertise, tools)

• Identifying and anticipating user needs o Trend and user surveys

7 Information on the number of projects is based on the programme’s final report in Finnish, MUOTO 2005 –

• Refining design firm concepts into products o Defining new procedures

According to the evaluation interviews, the requirement on the development of new procedures clearly restricted the number of companies participating in the programme. Thus, the majority of participating companies already had experience in using design services and the will and resources to invest in developing procedures and processes associated with design. The theme, design, also attracted companies new to Tekes and these companies did not always have a clear picture of the way Tekes works. This resulted in some negative funding decisions. Simultaneously, some aspects of design were also part of other R&D projects outside the DESIGN 2005 programme.

Figure 2. The structure of enterprise projects.

Applications for research projects

Applications for research projects were held once a year (four times in total). There was no separate call for project proposals as regards research, but the proposals were given feedback and efforts were made to develop them further. The programme implemented 25 research projects funded by Tekes and a further eight projects funded by the Academy of Finland. The research projects involved all central research bodies in the design branch. Considering the general research volume in the branch, this investment in research was highly significant. The value of the Academy of Finland research programme amounted to approximately €2 million. The projects funded by the Academy of Finland were integrated in the DESIGN 2005 programme by including them with the DESIGN 2005 research projects co-ordinated by the Programme Manager hired by Tekes.

The year 2004 saw the interim evaluation of the research programmes.8 It compared the programme’s objectives and the expected results of the research projects and was based on a survey targeting the projects and expert interviews. The evaluation resulted in the following recommendations:

• Expand the research themes to the fields of business and usability and from the user perspective to a wider customer relations perspective

• Give more prominence to international aspects

• Take the results to grass roots level through activities such as company clubs

• Develop the branch from the perspective of small design firms, for instance by developing partnerships, networks and potential for international relations

• Promote anticipation methods that support business

However, according to evaluation interviews, the objectives or activities of the programme did not see any major changes as a result of the interim evaluation.

Programme activities

The programme organised a well-attended seminar approximately twice a year. The seminars typically attracted up to a couple of hundred people, as did the final seminar. This way, the seminars also reached many of the programme’s project participants. The programme also explained its activities to external bodies, such as the management and R&D directors of member companies of Technology Industries of Finland, members of the SME Foundation, advertising agencies and the Association for Finnish Work. In addition, regional events to market the programmes were organised early on in co-operation with Tekes’ MASINA technology programme. Other events included the ABC (A=academics, B=business, C=consultants) meetings organised in autumn 2004 and spring 2005, which presented research results. Researcher meetings were also organised under the auspices of the Academy of Finland part of the programme. Considering the total volume of funding, the programme invested substantially in the various events and activities. Interviewees agreed that the projects put a lot of money into such activities.

The programme’s communication activities were also more extensive than usual. They consisted of a monthly newsletter, a comprehensive website, and other communications to interest groups. As the hosting organisation for the Programme Manager, Technology Industries of Finland played a crucial role in promoting the programme. Research results were also presented in the Designfacts gazettes issued in 2005 and 2006, and Technology Industries of Finland publications. The programme’s publications have a dual role as textbooks and enhancers of corporate competence. As the programme progressed, the focus of programme activities and communications shifted from marketing the programme to taking the results to grass roots level and increasing interaction.

8 Auno, S., Maja, P., Oksanen, M., Vaittinen, V. (2004) MUOTO 2005 –Teknologiaohjelman väliarviointilausunto,

The programme promoted internationalisation by fact-finding missions to Japan and the USA and by encouraging the projects to engage in international co-operation. The programme was unique by European standards and has attracted much international attention.

3 Evaluation of the programme’s implementation and results

3.1 Projects that responded to the survey

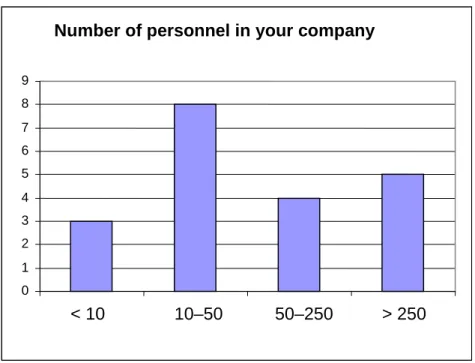

A total of 35 projects (17 research institutes and 18 companies) responded to the web survey and the supplementary interviews. Nine of the respondent projects were still ongoing. Of the research institutes, 16 respondents were universities and one a polytechnic. The funding for the majority of the respondents came from Tekes, with the Academy of Finland funding two projects. Most of the respondents represented small companies with 10–50 employees (Figure x.3). Comparison of the distribution of the respondents with the size distribution of all the companies that received funding shows that the respondents are representative of the project participants as regards their size.

Figure 3. Number of respondent companies by size.

The nature of the projects relative to the other activities of the organisation are illustrated in figures x.4 and x.5. As regards research projects, the results indicate that the subject matter was quite new to many of the research project implementers. It was new to many of the companies as well. The company responses indicate a slightly smaller research orientation than in other evaluated Tekes programmes. This is a natural illustration of the development of new procedures required in the programme.

Number of personnel in your company

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 < 10 10–50 50–250 > 250

Figure 4. The nature and significance of research projects relative to the other activities of the organisation (1=very low… 5=very high, N=17)

Figure 5. The nature and significance of enterprise projects relative to the other activities of the organisation (1=very low… 5=very high, N=18)

Companies: Relative to your organisation’s other activities,

assess the project’s … (1=very low … 5= very high)

0 % 20 % 40 % 60 % 80 % 100 %

strategic business significance

technological demands

research orientation

association with completely new areas of expertise

association with existing area of expertise

connection to other projects in your organisation

level of risk relative to achieving goals

1 2 3 4 5 no opinion

Research bodies: Relative to your organisation’s other activities,

assess the project’s … (1= very low … 5= very high)

0 % 20 % 40 % 60 % 80 % 100 %

strategic business significance

technological demands

research orientation

association with completely new areas of expertise

association with existing area of expertise

connection to other projects in your organisation

level of risk relative to achieving goals

1 2 3 4 5 no opinion

3.1 Programme results relative to the objectives

The objectives set for the programme were quite general in their nature. Their role was further specified as the programme progressed. Below, we will first look at the results of the programme from the perspective of three general objectives and then highlight some other observations about the results.

Developing the standard of research on design

As regards research, the programme endeavoured to cover the thematic fields set for the programme (Figure 1). This was a new field of research to both research organisations and Tekes, and many projects therefore produced basic scientific knowledge on design. Tekes also aimed at strengthening research in the field. The roles of Tekes and the Academy of Finland complemented each other in covering the entire field of research on the chosen themes. However, this research cannot be clearly defined into basic or applied.

At this point, the content of research has largely explicated procedures and systemised methods. New knowledge has been generated in design process management, the methods of user-oriented design and, in particular, thanks to research by the Research Institute of the Finnish Economy, ETLA, into the significance of industrial design in business. Some of the themes, such as user-oriented design, seem to have become emphasised. The programme’s interim evaluation, for instance, criticised the way research questions were limited to user analysis instead of a broader view of customer orientation. According to the interviews, not all the themes attracted sufficiently good project proposals. This is indicative of the lack of research in that particular area. Indeed, it can be estimated that allocating available funding to only some of the themes was a better solution research-wise than dispersing the funds to all the various themes.

In addition to actual research results, the interviews highlighted the fact that the significance of research in the branch has become clearer. The roles of various research bodies have become better defined and co-operation has increased. Funding by the programme has created critical mass and volume to research. Approximately 100 researchers have been involved in research linked with the programme, and this has given rise to a new research community. Indeed, it can be estimated that, considering previous research in the field, research funded by the programme attracted an exceptionally large number of researchers. This clearly increased the number of researchers with experience in the branch. As the research volume and tradition were quite limited when the programme began, it can be assumed that a major portion of the funding went into creating research prerequisites in the field: increasing general research competence, building teams, increasing awareness of the themes, and selecting the focuses of the teams. However, as regards polytechnics, the responsibility for research largely rested on individuals. This field of scientific research is also new to Tekes, so it has been a time of searching for best practices.

It is estimated that the programme promoted work on approximately 20 doctoral dissertations, although many of them are, as yet, unfinished. As the completion of doctoral

dissertations within the technology programme is a challenge, their completion is largely dependent on other funding. The publications generated by the programme are listed in an appendix to the final report. What strikes the eye in the list is the small number of articles in refereed international journals. This is partly due to the research tradition in design and the emphasis on conferences as a channel for making research results public. Some of the conferences in the field have strict peer reviews and selection based on articles but for the most part, it is a question of the limited experience of the programme’s participant researchers with international scientific publications. This kind of research culture is not created instantaneously. Part of the programme has been to create research tradition, but maintaining a community of researchers after the programme is a challenge. The fact that the Academy of Finland part of the programme continues until 2007 mitigates this effect for some research groups.

According to the evaluation interviews, the results of the programme had not, research-wise, reached the level of top international standard yet. However, the investments by Tekes and the Academy of Finland have been significant and raised the standard of research, and Finnish researchers have largely achieved the international standard. Although the investment has, at his point, been in strengthening Finnish competence, the number of international research contacts has also significantly increased. The research projects have actively encouraged international co-operation and the fact-finding missions organised within the framework of the programme have also contributed to international networking although the programme did not target any funds specifically towards internationalisation. Dissemination of the results both academically, particularly in international forums, and among companies, is still going on. One of the research project bottlenecks has been the scarcity of companies with experience in strategic design issues, resulting in few potential partners.

The results of the survey reveal that the benefits of the research projects are widely distributed among general awareness of the branch, the development of research services by research institutes, and the enhancement of corporate processes and competence. The impact on education has been negligible. (Figure X.6)

Figure 6. Assessment of the most important impacts of the research projects (percentage of those who mentioned the benefit of all the respondents, N=17)

Developing the utilisation of design in product development and business strategies

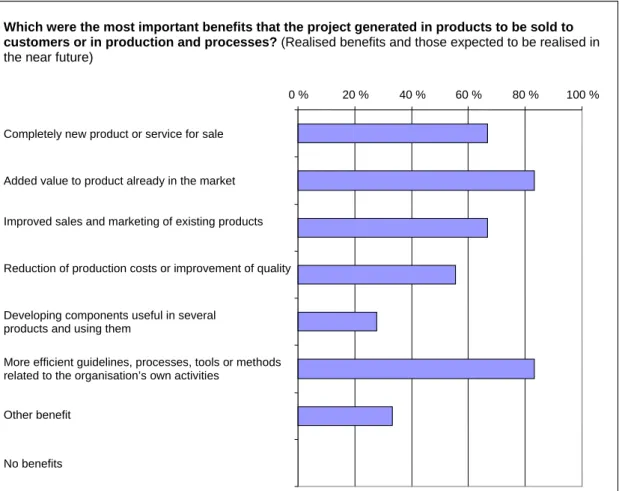

Enterprise projects (including both design firms and industry companies which utilise design) have given rise to both direct benefits associated with products and production, and more efficient procedures in corporate processes, for instance in product development (Figure xx). A great many of the projects have been able to produce entirely new products or added value to existing products. Operating procedures have also improved in 80% of the respondent companies. It can be assumed that this will have a long-term impact on the participant organisations. Several examples of successful new procedures came from the boat industry, for instance. In addition to concrete benefits in product design, the companies also widely reported on desired changes in procedures. Thus, the programme can be said to have achieved its objectives well in this respect. The decision to exclude projects only concerned with product design was, with hindsight, a good idea, as judged by the results achieved by participant companies.

The most important effect of new knowledge or expertise created by the project are generally…

0 % 20 % 40 % 60 % 80 % 100 %

Increasing awareness of the importance

Increasing standards of Finnish research in the branch

Improving education in the branch

Improving ability of research institutes to offer research services of interest to customers

Producing or developing products or service innovations

Improving production or processes by companies (incl. product development)

Increasing know-how of companies

Figure 7. Assessment of the benefits of the enterprise projects (percentage of those who mentioned the benefit of all the respondents, N=18)

According to the evaluation interviews, the number of companies that participated in the programme was somewhat restricted by their limited scope of design competence. The requirement of developing new procedures therefore resulted in more limited participation by companies which already had activities associated with design. This limited participation by SMEs with little previous experience of design. However, such initial design projects can benefit from the supported Design Start expert service provided by the TE Centres. The lack of concrete design experience was also evident in the fact that design issues were not in the domain of R&D management, which is the traditional Tekes contact within companies. This will be a challenge for Tekes in programmes associated with the development of business know-how. In general, experience shows that industries utilising design are difficult to actively involve in Tekes programmes. Therefore, taking the results of this programme to grass roots level in a wider selection of companies will be difficult.

However, it is estimated that the visibility of design has considerably increased due to this programme and other related actions. For instance, media visibility of the branch has increased. It is safe to assume that the companies that became involved with the programme from the beginning were already interested in the theme, regardless of the programme. Towards the end of the programme, new small companies were showing an interest.

Which were the most important benefits that the project generated in products to be sold to customers or in production and processes? (Realised benefits and those expected to be realised in the near future)

0 % 20 % 40 % 60 % 80 % 100 %

Completely new product or service for sale

Added value to product already in the market

Improved sales and marketing of existing products

Reduction of production costs or improvement of quality

Developing components useful in several products and using them

More efficient guidelines, processes, tools or methods related to the organisation’s own activities

Other benefit

Developing the competence of design firms and strengthening their service operations

The programme reached a limited number of design firms. A great number of small design firms were left outside the programme and the participants were mostly larger ones. However, those who participated reported that the projects brought them new products or added value to existing products. These results are given together with other enterprise projects in Figure 7.

According to the evaluation interviews, the more strategic role of design firms is still mainly only emerging. Likewise, the capability of such agencies to receive scientific information and utilise it in their business is still poor. From the perspective of renewing the branch, the programme has been hampered by its limited coverage. The objective of changing the structures in the branch should therefore, particularly as regards small design firms, have been tackled with means other than traditional enterprise projects. On the other hand, the programme has added to the potential to establish research-based companies, and this can have a renewing effect on the branch, together with existing companies.

Other results of enterprise projects

All the companies that responded to the survey felt that the enterprise projects had an impact on their competitive position. Eight of the 11 companies that responded to the question chose the alternative “We have developed new products or achieved savings in costs, which have resulted in an advantage or opened up entirely new business opportunities”. This can be considered an outstanding result.

In addition to benefits related to concrete products, production or procedures, the general level of expertise and competence in the companies improved. Approximately 60% of the respondent companies reported an increase in technological know-how, and information about potential partners, the market, customers, and competitors.

The programme’s added value

Looking at the benefits the programme gave to research projects, the results indicate that the programme’s activities, other than funding, supported a surprisingly small share of the projects. This situation is illustrated in Figures X.8 and X.9.

Figure 8. Evaluations by research projects on the significance of the various forms of programme activities relative to the results achieved by the project (N=17).

As regards research bodies, the most important benefits of the programme were associated with co-operation with other research bodies as well as the information and knowledge produced by them. According to the survey, mutual co-operation by research institutes has been significantly more important for the project’s results than co-operation between companies and research institutes. Other benefits of the programme were concentrated on a small number of the projects.

Assess the significance of the following from the perspective of the benefits gained through the project on a scale from 1 to 5

0 % 20 % 40 % 60 % 80 % 100 %

Financial support through programme

Co-operation with research bodies created by programme

Co-operation with companies created by programme Programme’s support in finding partners during preparation stage

Knowledge generated by programme’s research bodies

Information transfer from other projects (seminars, publications etc.) New ideas offered by programme outside project, which resulted or will result in further development projects Co-operation partners for further projects outside programme found through programme Reports and studies carried out within programme (e.g. market analyses, strategy work in the branch) Contacts to customers provided by programme or better understanding of customer needs

Assistance in internationalisation provided by programme

1 2 3 4 5 no opinion

1=low, the same results would have been achieved in the same time even without the programme 5=high, the results would have been impossible without this

Figure 9. Evaluations by companies on the significance of the various forms of programme activities relative to the results achieved by the project (N=18).

Judging by responses, the average benefit of the programme to companies was greater than that to research bodies. The most important benefits were (in addition to funding) co-operation with other companies and contacts with customers. However, no specific form of programme activities emerged as especially important.

Other benefits of the programme

Naturally, not all the benefits of the programme were realised through the programme projects. The respondents thought the role of the programme projects and the general impact of the programme was significant in increasing competence and expertise in the branch.

Companies: Assess the significance of the following from the perspective of the benefits gained through the project on a scale from 1 to 5

1=low, the same results would have been achieved in the same time even without the programme 5=high, the results would have been impossible without this

0 % 20 % 40 % 60 % 80 % 100 %

Financial support through programme

Co-operation with research bodies created by programme Co-operation with companies created by programme

Programme’s support in finding partners during preparation stage Knowledge generated by programme’s research bodies

Information transfer from other projects (seminars, publications etc.) New ideas offered by programme outside project, which resulted or will result in further development projects

Co-operation partners for further projects outside programme found through programme Reports and studies carried out within programme

Contacts to customers provided by programme or better understanding of customer needs Assistance in internationalisation provided by programme

1 2 3 4 5 no opinion

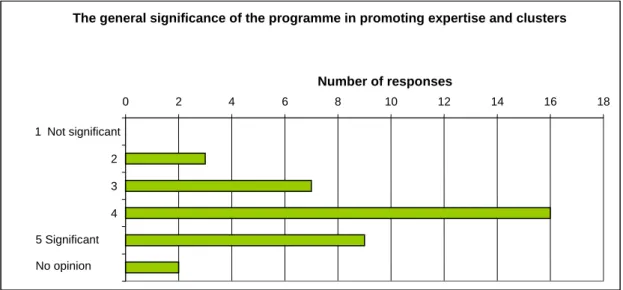

Figure 10. Evaluation of respondents on the general significance of the programme in promoting expertise and clusters.

The interviews suggest that the key benefit of the programme was that the branch became more organised and concrete contacts were created, especially among researchers. The interviewees also thought that design firms became more ambitious and more business-oriented. People in the branch also became more willing to learn new things.

Interviewees felt that the programme succeeded in reaching the various players in the design branch and making them more active. People and institutions in the branch were aware of the programme, although not all participated in it. Important actors, both smaller design firms and users, were left outside.

The programme also developed the identity of industrial design. Applied art, such as fashion, furniture and tableware, has traditionally been seen as the core of the branch, although industrial design also has strong traditions. The programme, however, focused on more traditional manufacturing industries, such as the metal industry, which are active customers of Tekes. The programme was apparently able to increase awareness of industrial design in these industries.

The interviewees emphasised the change in strategic thinking which was promoted by the programme. Their view of the role of design had changed. It was not only seen as mere aesthetics, but as part of innovation. As the programme progressed, more concept design was included. Expertise consists of the ability to visualise what is needed and being able to combine it with what is technically possible. The aim is to create an overall view of what is necessary for a product (which can naturally also be a service product) that works both internally and externally. This is a new way of thinking. In this programme, Tekes assumed a new, wider role in addition to its traditional one that emphasised technology.

3.2 Deployment of the results in companies

The general significance of the programme in promoting expertise and clusters

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 1 Not significant 2 3 4 5 Significant No opinion Number of responses

Programme activities and communication were exceptionally extensive in the DESIGN 2005 programme. There were also sufficient resources for this. The prerequisites for deploying the results were good as far as the programme activities were concerned.

At the project level, significant resources were spent in developing prerequisites and tradition. According to the survey, the results of the research projects did not generally play a major role in the benefits generated by the programme’s enterprise projects. The companies that participated in the research projects felt that the benefits were mostly in improved knowledge and awareness. Research results were also mostly quite far removed from the everyday life of the companies.

A general observation from the interviews is that companies lack structures to receive design information and knowledge. Most companies do not have experience of a more strategic handling of design issues and few companies have a separate design unit. On the other hand, design firms are not able to give advice on developing procedures and structures as the more strategic role is still in the background. However, awareness and interest have increased. Good examples of companies that invest in design, such as Nokia, Metso, Suunto, Finn Power and Lappset, are also beginning to emerge.

Deploying the programme’s results in design firms has been and will be a challenge. Changing their role towards design consultancy will presumably be slow because the companies have only limited resources and basic business know-how. How to change the structures of the branch should also be addressed. Design firms are not traditional Tekes customers, so the role of Tekes in developing the branch needs to be reassessed.

An important result from the perspective of the design branch and later utilisation of the results is that it has been possible to integrate design into the innovation system, including Tekes’ activities. Tekes can use such sources as TUPAS funding to spread the results and take them to grass roots level. This has also been applied in the design branch. The design theme will remain on the culture, education, and research policy agenda, as the Ministry of Education is currently drawing up a Design 2010 programme. Continuing and postgraduate education centres at universities could play a major role in taking the results to grass roots level. The role of polytechnics in the deployment of results still needs to be clarified. Although polytechnics have strengths in teaching product design in particular, and are able to produce related services, they have limited resources and capability to transfer their research know-how to their teaching and on to companies. In this sense, the polytechnics are still searching for their role in the field of design-related innovation.

3.3 Programme management and the functionality of the joint programme model

According to the interviews, co-operation between Tekes and the Programme Manager was smooth and the Programme Manager’s interaction with Tekes was active. From the point of view of the joint programme, it was considered particularly good that the Academy of Finland projects were co-ordinated by the same person.

As usual, the Programme Manager from the outside was not concerned with the details of the enterprise projects. His role was mostly to market the programme and provide support for research projects. Communications in particular played a key role in this programme and were the responsibility of the Programme Manager. The contact network of Technology Industries of Finland proved useful and brought credibility to the programme.

In accordance with Tekes’ normal procedure, the management group did not handle enterprise projects but focused in the general direction of the programme and research projects. Work by the management group was given a good grade in the interviews, although its role perhaps was not completely clear, especially towards the end of the programme. In practice, the management group mainly acted as a sounding board for the programme’s daily management and, thus, helped to draw programme policies. In the beginning, the management group also discussed research project applications and sought to improve and combine them. It comprised some of the most important people in the branch, who lent credibility to the programme. They had a crucial role in the beginning of the programme because design as a branch was not yet established at Tekes. The management group showed the way, especially in the initial stages of the programme. However, the prestigious group had limited opportunities for assuming a more active and operative role. In general, work by a programme’s management group underpins the fact that management groups are an important resource for Tekes.

The Academy of Finland programme had its own management group. It was crucial for the reconciliation of activities that some people were members of both management groups. A shared Programme Manager was also important for successfully combining the two programmes. The Academy of Finland supervised the projects across the board to a lesser degree than Tekes. Nevertheless, following a suggestion by the Programme Manager, the projects funded by the Academy of Finland also engaged in annual performance negotiations. They were an important element in binding the projects to Tekes’ DESIGN 2005 programme.

On a general level, the Academy of Finland and Tekes shared a common view on the objectives and methods of the programme. On a practical level, information flowed freely: for example, the Academy assessed Tekes applications and vice versa. The fact that the Academy of Finland application process was not continuous reduced the need for constant contacts.

Co-ordination of the programme continued until the end of 2006. It is a happy solution for the aftercare of Tekes’ programme. However, organising information dissemination and other activities at the end of the Academy of Finland programme in 2007 will be a challenge.

4 Programme impact from the perspective of joint programme

evaluation

Tekes had no previous experience of programme activities in industrial design, so the DESIGN 2005 programme differed from other evaluated Tekes programmes in this respect. One of the main impacts of the programme was to create a vision of the research activities

connected to the design branch (Figure 1). It is a strategic vision of the necessary areas of expertise. Co-operation with the Academy of Finland was mostly associated with funding complementary research themes. A joint programme creates a critical mass and credibility while promoting wider coverage and co-ordination.

A central challenge in programme co-operation was the timing of the programmes. The Academy of Finland programme began approximately two years after the Tekes programme. This delay thus poses a challenge in the deployment of research results as the projects continue after the Tekes programme wraps up. On the other hand, this evens out the transitional phase after the technology programme funding ends. It is also probable that researchers will seek other Tekes programmes, such as LIITO and SERVE to ensure continuity.

In conclusion, we can say that expertise and know-how in many areas of design has improved and strengthened. The branch has seen the emergence of new research bodies, such as the Institute for Design Research and MUOVA, which became a joint research and product development centre of the University of Art and Design Helsinki and University of Vaasa this spring. All universities have commented on the activities in the branch, but the key question for developing expertise and know-how in the field is where to find funding for research and development in the future.

Then again, design cannot be thought of as a separate field of expertise independent of other fields of expertise and applications. Design experts should therefore be involved in several branches.

5 Summary and conclusions

The objectives of the DESIGN 2005 programme were to promote design research, renewal of design firms, and expansion of service provision towards a more strategic direction, and the utilisation of design in industrial companies. The programme thus took a broad view of the renewal of the design branch, encompassing basic scientific knowledge, service

provision, and demand for design services. The programme was very timely, considering recent international developments in the field of design.

The programme has been a success from the point of view of research and general expertise in the branch. When the programme began, research know-how in the branch was scarce and the programme has significantly promoted its growth. Research themes and the role of research in the branch have also become clearer. New research capabilities have been created. However, disseminating the research results, both in the academic and business worlds, is not yet finished. Utilisation of the results and combining research and business are still a challenge. Investment in the development of tools and methods will be necessary in the future.

As the programme draws to a close, a central question is how to best make use of the body of researchers trained during the programme. The programme was a short, intensive

benefits can be gained either by continued research activities, or by people with research experience offering their services to the corporate world.

It is important for the future development of the branch that design has now been included in Tekes’ agenda. However, the role of Tekes in the overall development of the branch is still open, especially as regards research and the development of design firm operations. More measures and positive examples are necessary for design to really take root in the industry. In this area, Tekes clearly has a lot to offer.

When looking at the benefits gained by design firms and industrial companies that

participated in the programme, the results indicate that the programme was successful in the development of new procedures as well as new products. The requirement on enterprise projects to develop procedures was a good choice from the point of view of participant companies and the benefits they received. Development of procedures and support for SMEs in this programme will benefit Tekes’ new programmes pertaining to business know-how. However, the requirement of developing new procedures somewhat limited

participation, and taking the things learned in the programme to grass roots level, especially to SMEs, is a challenge for the future. Possible ways of spreading the results could be:

• Taking the results to grass roots level through such channels as company clubs, as suggested in the programme’s interim report

• Integrating the results in the Design Start service offered by TE Centres

• Compiling the procedures created in the programme into a best practices report that would promote the development of corporate activities

Participation by design firms was clearly limited by their small size. Engaging in Tekes projects of their own may not be the best way. Renewal of the branch would require partnerships and the development of networks and international contacts, which were already called for in the interim report. International competition can be expected to become stiffer and, as a result, the corporate structure in the branch will change, like it has in other consultancy and business service branches. Developing the branch in a more strategic direction, taking into account the perspective of small design firms, is a key challenge in the future.

The programme played a key role in increasing awareness of the function of industrial design, and simultaneously, the programme succeeded in creating co-operation in a branch that comprises many different players. The benefits of co-operation have best been realised in the collaborative work between various research bodies. Fostering the emergent cluster and research know-how is, however, a central challenge for the future.