Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=wscs20

Download by: [148.251.235.206] Date: 14 February 2016, At: 07:21

Smith College Studies in Social Work

ISSN: 0037-7317 (Print) 1553-0426 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wscs20

Rising to the Challenge of Treating OEF/OIF

Veterans with Co

‐

occurring PTSD and Substance

Abuse

Alan Bernhardt

To cite this article: Alan Bernhardt (2009) Rising to the Challenge of Treating OEF/OIF Veterans with Co‐occurring PTSD and Substance Abuse , Smith College Studies in Social Work, 79:3-4, 344-367, DOI: 10.1080/00377310903115473

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00377310903115473

Published online: 22 Oct 2009.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 3312

View related articles

Rising to the Challenge of Treating OEF/OIF

Veterans with Co-occurring PTSD and

Substance Abuse

ALAN BERNHARDT

Northampton Veteran Affairs Medical Center, Leeds, Massachusetts, USA

This article reviews data on the relatively high incidence of Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) veterans reporting mental health and substance abuse problems, and some perceived barriers that may account for low rates of their engaging in treatment. Treatment outcomes for veterans with co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance use disorder (SUD) are generally poorer than for those with PTSD or substance abuse alone. Several evidence-based individual therapy approaches offered by VA Medical Centers are described along with how they conceptualize the relationship of substance abuse to PTSD. Problems with sequential treatment for persons with PTSD and substance abuse in specialized programs are discussed, including notably the practice of requiring veterans to be completely drug and alcohol free for a month or longer prior to entering PTSD treatment. Several integrated treatment programs are described along with a brief summary of evidence supporting their effectiveness. Some recent policy changes from the Department of Veterans Affairs that bode well for the future of PTSD/SUD treatment are described. Differences between younger and older veterans were cited along with their implications for treatment. Recommendations regarding how to better engage and retain OEF/OIF veterans with PTSD/SUD in treatment are presented together with examples of their implementation. The author concludes that to rise to the challenge of treating this difficult population it is necessary to adapt treatment to meet their

344 This article not subject to US copyright law. Received February 9, 2009; accepted May 29, 2009

Address correspondence to Dr. Alan Bernhardt, Northampton Veteran Affairs Medical Center, 421 North Main Street, Leeds, MA 01053, USA. E-mail: alan.bernhardt2@va.gov Copyright#Taylor & Francis

ISSN: 1753-5654 print / 1753-5662 online DOI: 10.1080/00377310903115473

needs rather than requiring them to adapt to therapies that may not be a good fit.

KEYWORDS trauma, addiction, engagement, integrative treatment

To date, the United States has deployed more than 1.7 million Americans to Iraq and Afghanistan. Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) began in Afghanistan in October 2001 and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) began in Iraq in March 2003. Veterans who have returned from these wars present special challenges for mental health professionals attempting to engage them in treatment. This article will (1) review data on the frequency with which OEF/OIF veterans report mental health and substance abuse problems; (2) review how the co-occurrence of posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorders (PTSD/SUD) affects treatment outcomes; (3) summarize how several treatment modalities for PTSD currently practiced within the VA system conceptualize the relationship between PTSD and substance abuse and approach treatment; (4) discuss problems with sequential treatment of PTSD/SUD; (5) describe several integrated treatment programs and their results in treating PTSD/SUD; (6) describe some promising developments within the VA system and future challenges for treating veterans with PTSD/SUD; and (7) make recommendations for successfully engaging and retaining OEF/OIF veterans with PTSD/SUD in treatment along with examples of how they can be implemented.

Because the majority of Veterans with PTSD/SUD currently are male, to avoid unnecessary verbiage, the male gender is used throughout when referring to clients. The views expressed in this article represent the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U. S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

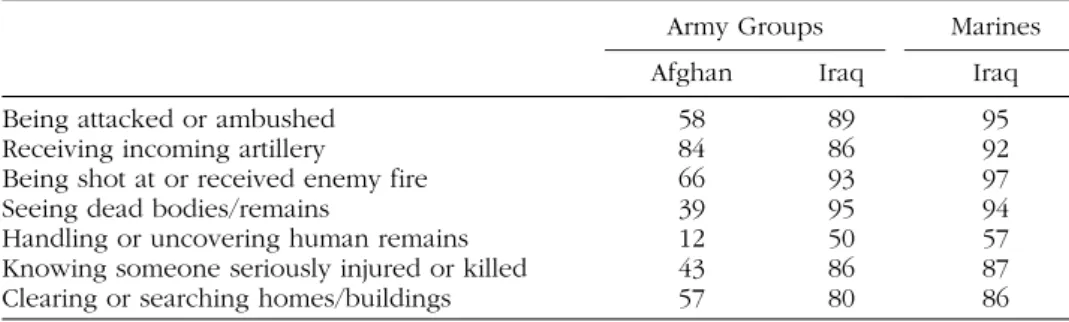

According to one survey (Hoge et al., 2004), a high percentage of Army and Marine soldiers serving in Iraq and Afghanistan experienced heavy combat trauma. For example, 95% of Marines and 89% of Army soldiers serving in Iraq experienced being attacked or ambushed, and 58% of Army soldiers serving in Afghanistan experienced this. High percentages for these three groups also experienced incoming artillery, rocket, or mortar fire (92%, 86%, and 84%, respectively), saw dead bodies or human remains (94%, 95%, and 39%, respectively), or knew someone seriously injured or killed (87%, 86%, and 43%, respectively). (See Table 1 below for data on other combat stressors.) Clearly a very large number of combatants returning from these two wars meet ‘‘Criterion A’’ for a diagnosis of PTSD: ‘‘Exposure to extreme

traumatic stressor with response of extreme fear, helplessness or horror’’ (American Psychiatric Association, 1994, p. 424). OEF/OIF soldiers are also subjected to a variety of other stressors that, although they do not meet this criteria for the diagnosis of PTSD, contribute to their overall level of stress and undoubtedly increase the likelihood of their having PTSD symptoms. These include hearing loud noises from gunfire and artillery, fatigue and exhaustion, sexual harassment, fear of the unknown, loss of control, austere living conditions, separation from family, and lack of sleep (Committee on Gulf War and Health, 2008).

It is important to acknowledge that many Veterans, male and female, suffer from PTSD as a result of sexual abuse experienced either in the military or in civilian life or both. It is beyond the scope of this article to report statistics on the incidence of this problem or the number of Veterans who have experienced combat and sexual trauma. The VA offers treatment to all Veterans with PTSD regardless of the source of their trauma, although some programs specialize in treating combat trauma. Several therapies that are currently being promoted by the VA, cognitive processing therapy and prolonged exposure, were developed with victims of sexual assault.

In their landmark study, Hoge and colleagues (2004) studied the prevalence of various mental health problems among thousands of Army and Marine soldiers prior to and 3 to 4 months following their deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan. The study found that 17% of soldiers returning from the Iraq war (OIF) and 11% of those returning from Afghanistan (OEF) met criteria for a diagnosis of PTSD on the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL) (Blanchard et al., 1996). A subsequent study by Hoge, Auchterlonie, and Milliken (2006) reported that 19% of all Army soldiers and Marines returning from Iraq and 11% of those returning from Afghanistan reported a mental health problem on a post-deployment mental health screening during a 12-month period from May 1, 2003 to April 30, 2004.

Hoge et al. (2004) found 24% of returning OEF/OIF service members responded affirmatively when asked if they ‘‘used alcohol more than they

TABLE 1 Percentage of Military Combatants in Iraq and Afghanistan who Experienced Various Kinds of Combat Trauma

Army Groups Marines

Afghan Iraq Iraq

Being attacked or ambushed 58 89 95

Receiving incoming artillery 84 86 92

Being shot at or received enemy fire 66 93 97

Seeing dead bodies/remains 39 95 94

Handling or uncovering human remains 12 50 57

Knowing someone seriously injured or killed 43 86 87

Clearing or searching homes/buildings 57 80 86

Source: Hoge et al. (2004).

meant to?’’ Twenty-one percent of OIF and 18% of OEF service members responded affirmatively when asked if they felt they ‘‘wanted or needed to cut down?’’ indicating high rates of alcohol abuse in this population. Milliken, Auchterlonie, and Hoge (2007) reported 12% of soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan endorsed alcohol misuse. In a large scale study, Jacobson et al. (2008) reported that Reserve or National Guard personnel who were deployed and had combat exposure in Iraq or Afghanistan were significantly more likely to experience ‘‘new onset’’ heavy weekly drinking, binge drinking, and alcohol-related problems (9%, 53%, and 15 %, respectively) compared with ‘‘new onset’’ rates for nondeployed personnel (6%, 26.6%, and 4.8%, respectively).

Estimates of the percentage of OEF/OIF Veterans in substance abuse treatment, who also concurrently meet criteria for PTSD, are typically around 30%. Seal et al. (2008) reported that of 750 OEF/OIF Veterans screened at a VA Medical Center from June 2004 through September 2006 for mental health problems, 59% screened positive for depression, 50% for PTSD, 46% for high risk alcohol abuse, and 19% were positive for all three. Brady, Back, and Coffey (2004) reported that between 36% and 50% of individuals (not necessarily veterans) seeking treatment for an SUD meet criteria of lifetime PTSD. Zatzick et al. (1997) reported that approximately one third of male Vietnam Veterans with alcohol abuse or dependence, and 56% of those with drug abuse or dependence met criteria for PTSD. Estimates of the percentage of Veterans seeking PTSD treatment, who also have some history of substance abuse, are between 60% to 80% (Kofoed, Friedman, & Peck, 1993). Aside from data confirming the high incidence with which these two disorders co-occur, patients themselves frequently report the functional relationship between their substance abuse and PTSD symptoms (Back, Brady, Jaanimagi, & Jackson, 2006).

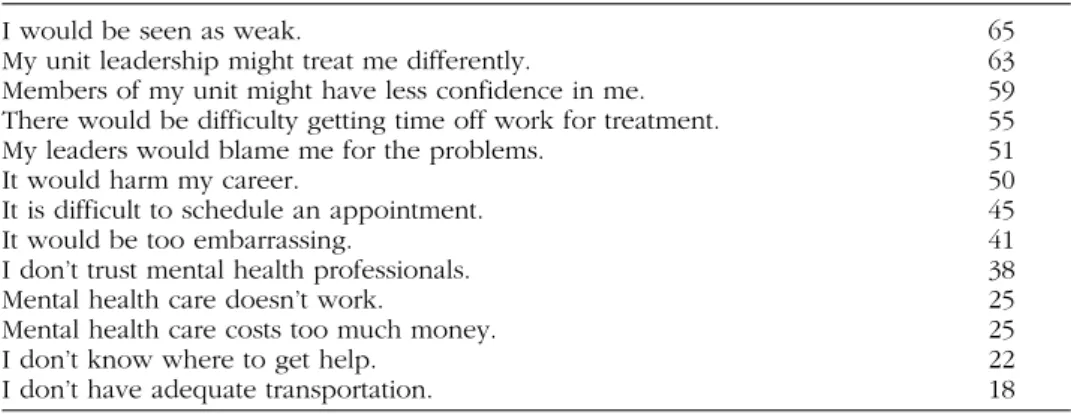

THE EFFECT OF DUAL DIAGNOSIS ON TREATMENT OUTCOME Persons dually diagnosed with PTSD and substance abuse more often avoid treatment than seek it. Hoge et al. (2004) reported that only 38% to 40% of OEF/OIF soldiers whose responses on a post-deployment mental health screening met strict criteria for a mental disorder (i.e., required substantial self report of functional impairment or a large number of symptoms) indicated an interest in receiving help, and only 23% to 40% received professional mental health care in the previous year. The stigma associated with seeking help was cited as an important barrier to Veterans receiving the care that they need. (See Table 2 for a list of other perceived barriers to seeking mental health cited by soldiers participating in Hoge’s study.) These barriers are compounded by the presence of a substance abuse problem.

There are clear implications for policy makers and clinicians to reduce the perception of stigma and other barriers to mental health care.

For those persons with PTSD/SUD who do seek treatment, there is evidence that their prognosis is poorer than for persons diagnosed with only one or the other disorder. Hien, Nunes, Levin, and Fraser (2000) reported that substance abuse treatment patients with PTSD report significantly more drug use at admission, have poorer treatment adherence, and exhibit more substance use at 3-month follow-up. Back et al. (2000) reported higher rates of Axis I and II diagnoses and more severe symptomatology in a sample of cocaine-dependent individuals with PTSD compared to those without PTSD. Ouimette and colleagues (Ouimette, Ahrens, Moos, & Finney, 1998; Ouimette, Finney, & Moos, 1999) reported that treatment outcomes for PTSD/SUD patients are worse than for other dually diagnosed patients as well as for patients with substance abuse alone. Ouimette, Moos, and Finney (2003) reported that the exacerbation of PTSD symptoms may be the most important factor in predicting relapse to illicit drug use or problematic alcohol use following intensive SUD treatment among those dually diagnosed with PTSD and substance abuse.

HOW INDIVIDUAL PTSD TREATMENTS WORK AND HOW THEY VIEW SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Cognitive processing therapy (CPT) (Monson et al., 2006; Monson & Rizvi, 2007; Resick, 2001; Resick & Schnicke, 1992), one of two evidence-based therapies promoted by the Department of Veterans Affairs (2008), views the PTSD sufferer’s substance abuse as one of many forms of ‘‘externalizing’’ avoidance strategies that seek to reduce strong negative emotions. Other avoidance strategies include ‘‘internalizing,’’ such as social withdrawal,

TABLE 2 Perceived Barriers to Seeking Mental Health Services among Soldiers: Percentage of Respondents Who Met Screening Criteria for a Mental Disorder

I would be seen as weak. 65

My unit leadership might treat me differently. 63

Members of my unit might have less confidence in me. 59

There would be difficulty getting time off work for treatment. 55

My leaders would blame me for the problems. 51

It would harm my career. 50

It is difficult to schedule an appointment. 45

It would be too embarrassing. 41

I don’t trust mental health professionals. 38

Mental health care doesn’t work. 25

Mental health care costs too much money. 25

I don’t know where to get help. 22

I don’t have adequate transportation. 18

Source: Hoge et al. (2004).

anhedonia, numbing, and behavioral inhibition. The model views the ‘‘success’’ of the PTSD sufferer’s various avoidance strategies in escaping or avoiding negative emotions, notably by abusing substances, as obstructing the normal recovery process from occurring. CPT seeks to reduce the need to avoid strong negative feelings by altering the PTSD sufferer’s irrational thinking, which adds ‘‘manufactured emotions’’ to the natural emotions in response to their traumatic experience. CPT is a 12-session manualized therapy, which involves the client’s targeting his or her most traumatic event, writing a detailed account of it and how it affected his or her views regarding five areas: safety, trust, power and control, esteem, and intimacy. The client is then assisted in challenging his or her faulty thinking in each of these areas utilizing education and Socratic questioning. To the extent that CPT successfully reduces the client’s overall negative emotions, they will experience less need to avoid through substance abuse. The interested reader will find a thorough review of the evidence supporting CPT as well as a wide range of other treatment modalities including those summarized below and one that conspicuously is not, Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) in Foa et al. (2009). See Silver et al. (2008) for further information about EMDR.

Prolonged exposure (PE) therapy (Foa, Keane, Friedman, & Cohen, 2005; Riggs, Cahill, & Foa, 2006) is another evidence-based treatment of PTSD that the VA offers. PE, like CPT, emphasizes the role of avoidance and negative beliefs in impeding a natural recovery from PTSD. PE is based on emotional processing theory that states that PTSD results when a traumatic event becomes represented in memory as a ‘‘fear structure’’ that includes a large number of stimulus items associated with danger. The resulting erroneous cognitions about the world and the self contribute to the view that the world is dangerous and lead to avoidance. Therapy involves activating the fear structure through imaginal exposure to the traumatic event and in vivo exposure to avoided people, places, and activities along with information that is incompatible with the fear network (safety and absence of feared consequences) that repeatedly disconfirm the negative associa-tions. PE typically consists of 9 to 12 sessions of 90-minute duration. The client repeatedly describes his imaginal experience of the traumatic event following which the therapist assists him in processing the resulting thoughts and feelings. Homework is then given to listen to a recording of the session and engage in in vivo exposure to previously avoided situations. PE has been shown to be an effective treatment for PTSD in numerous studies with a wide range of traumatic experiences. To the extent that PE decreases the fear structures, PTSD symptoms improve, and the clients would have less need to avoid through substance abuse. Back et al.’s (2006) finding that 63% of individuals with cocaine dependence and PTSD interviewed by the researchers reported that improvement in their PTSD symptoms was associated with a decrease in cocaine use provides support for this

hypothesized relationship. More research is needed to document whether improvements in substance abuse occurs following PTSD/SUD clients participation in PTSD treatment.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) (Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006), currently considered an evidence-based treatment for anxiety and depression and probably soon to be considered evidence based for PTSD, has gained widespread use in VA Medical Centers for PTSD. ACT views the PTSD sufferer’s substance abuse as an example of ‘‘experiential avoidance,’’ that is, an attempt to avoid unwanted and painful thoughts, feelings, and memories (private internal events) directly and indirectly related to the trauma. Private events that are directly related to the trauma may include vivid memories of the trauma and its associated feelings. Private events that are indirectly related to the trauma may include thoughts and feelings that are related to the pain associated with not living a life that is valued. Another problem that ACT focuses on is the clients ‘‘fusing’’ with painful memories such as flashbacks or with ‘‘rules’’ that instead of being viewed as merely thoughts are viewed as being literally true and prevent them from taking steps in a valued direction. ACT attempts to help clients accept internal experiences and ‘‘defuse’’ from thoughts that are keeping them stuck and preventing them from moving forward toward their values. Although recent studies of ACT suggest that it may be effective for a variety of disorders, including several anxiety disorders, depression, pain, and drug abuse (Pull, 2009), more research is needed to demonstrate its effectiveness as a standalone therapy for PTSD (Cahill, Rothbaum, Resick, & Follette, 2009).

PROBLEMS WITH SEQUENTIAL TREATMENT OF PTSD/SUD Specialized PTSD programs offered by VA Medical Centers have generally required that to be admitted veterans be abstinent of all drug and alcohol use for up to one month or more prior to entering treatment. To help them achieve sobriety they were generally referred to an intensive outpatient substance abuse treatment program. The problem with this approach is that many Veterans, who are in the habit of self-medicating for their PTSD symptoms with drugs and/or alcohol, find it difficult to give up their drug of choice to participate in a substance abuse program without getting help to deal with their PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, veterans, whose diagnosis is alcohol or drug abuse rather than dependency, often do not accept that they have a substance abuse problem or, even if they do, are generally not willing to commit to an abstinence-based 21-day intensive outpatient substance abuse program.

A key reason given for deferring PTSD treatment has been concern that focusing on PTSD while the client is in early recovery and does not possess requisite coping skills to handle the anxiety that will likely arouse may result

in relapse. This is evidenced by the following statement from a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) on the treatment of co-occurring disorders (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2005, p. 410): ‘‘By exploring trauma memories, well intentioned counselors inadvertently may drive a client back to the substance by urging her to ‘tell her story.’’’ To minimize the risk of relapse and/or exacerbation of an existing substance abuse problem, clients can be provided training in emotion regulation skills, such as grounding (Najavits, 2002) or elements of dialectic behavior therapy (Wagner & Linehan, 2006) to help clients tolerate trauma-focused interventions.

A major problem with requiring PTSD/SUD Veterans to completely abstain from alcohol and illicit drugs prior to engaging in treatment is that they often refuse treatment and continue to use substances to self-medicate for their PTSD symptoms. Alternatively, they may lie about their use to enter treatment or abstain from their drug of choice by ‘‘white knuckling’’ it, that is, with continued craving and poor lifestyle choices. Another possibility is that they enter treatment with an ‘‘attitude’’ that interferes with their benefitting from treatment. Because specialized PTSD programs typically do not address other factors that play an important role in maintaining the PTSD/SUD sufferer’s substance abuse, many program participants who remain abstinent prior to and during their PTSD treatment program continue their substance abuse in the long term.

Just as has been the case with dually diagnosed patients with serious mental illnesses and substance abuse, Veterans with PTSD/SUD have ‘‘ping-ponged’’ back and forth between settings that specialize in substance abuse treatment and settings that specialize in treating their psychiatric problem with neither setting adequately addressing the ‘‘other’’ problem. Furthermore, it appears that clinicians treating PTSD are from Mars and clinicians treating substance abuse are from Venus, because there generally has been no overlap between the staff of the substance abuse and PTSD programs, and staffs of both programs generally have little or no training and experience treating the ‘‘other’’ problem.

INTEGRATED TREATMENT APPROACHES

Concern that specialized programs, which fail to address the ‘‘other’’ problem, may not produce sufficient improvement in whichever problem (PTSD or substance abuse) is not specifically addressed, led to the development of various integrated treatment programs. These programs have combined successful elements of existing therapeutic programs for substance abuse and PTSD with promising results. The literature on the most effective treatment for patients diagnosed with serious mental illness and substance abuse clearly favors integrated treatment (Drake, Mueser,

Brunette, & McHugo, 2004; Mueser, Noordsy, Drake, & Fox, 2003). The same is likely to be true for the treatment of PTSD and substance abuse. For this reason, the National Center for PTSD recommends:

Treatment for PTSD and substance use problems should be designed as a single consistent plan that addresses both sources of difficulty together. Although there may be separate meetings or clinicians devoted primarily to PTSD or to substance problems, PTSD issues should be included in substance use treatment, and substance use (‘‘addiction’’ or ‘‘sobriety’’) issues should be included in PTSD treatment. (NCPTSD website)

As a result of accumulating evidence for the effectiveness of integrated approaches and policy changes based on this research, such as those cited below, we are likely to see movement in this direction in the future.

Lisa Najavits’ Seeking Safety program (Najavits, 2002), has gained popularity within VA Medical Centers over the past decade and is now widely adopted. This approach consists of up to 25 coping skill topics divided among four content areas: cognitive, behavioral, interpersonal, and case management. A key feature of this approach is that it addresses PTSD and substance abuse disorders simultaneously, usually in a group format. Each session teaches the client skills to work with both disorders as they are looking at the particular coping skill. Examples of topics are ‘‘Safety,’’ ‘‘PTSD: Taking back your power,’’ ‘‘Detaching from emotional pain,’’ ‘‘When substances control you,’’ ‘‘Asking for help,’’ ‘‘Getting others to support your recovery,’’ ‘‘Healthy relationships,’’ ‘‘Self-nurturing,’’ ‘‘Healing from anger,’’ and ‘‘Life choices.’’ The approach also focuses on ideals such as honesty, respect, and self-care, attention to therapist processes, uses everyday language rather than psychological jargon, and emphasizes practical solutions. Seeking Safety can easily be integrated with other treatment approaches. The approach has been empirically validated in numerous studies, including one with veterans in a VA Medical Center (Desai, Harpaz-Rotem, Najavits, & Rosenheck, 2008; Desai, Harpaz-Harpaz-Rotem, Rosenheck, & Najavits, 2009). Although early studies were conducted with female clients, several recent outcome studies have been conducted with men (Cook, Walser, Kane, Ruzek, & Woody, 2006; Najavits, Schmitz, Gotthardt, & Weiss, 2005; Najavits et al., 2009; Weaver, Trafton, Walser, & Kimerling, 2007). Currently it is the only model for PTSD/SUD defined as an ‘‘effective’’ approach based on research (Najavits et al., 2009).

Transcend, developed by Donovan and colleagues (Donovan, Padin-Rivera, & Kowaliw, 2001) begins with 12 weeks of intensive treatment with group and individual sessions focusing on decreasing PTSD symptoms and promoting an addiction-free lifestyle. It includes education on the relation-ship between PTSD and substance abuse, behavioral skills training, narrative type exposure emphasizing the meaning of the trauma, self-acceptance,

forgiveness, relapse prevention training, and gaining peer support. During the second phase of treatment clients attend a weekly group for six months, during which time they work on PTSD symptom management and relapse prevention. An uncontrolled pilot investigation with 46 Vietnam combat Veterans with substance abuse yielded significant reductions in PTSD symptoms upon completion of the program but substance use was not assessed as participants were required to be abstinent for 30 days prior to and for the duration of treatment (Donovan et al., 2001).

Substance dependence PTSD therapy (SDPT), developed by Triffleman, Carroll, and Kellogg (1999), consists of twice-weekly individual therapy over a month period designed for use in mixed-gendered civilians with varied sources of trauma. During the first phase of treatment clients meet individually with their therapist with the focus on cognitive-behavioral treatment utilizing relapse prevention and coping skills training for substance abuse. During phase two the focus is on psycho-education, stress inoculation training, andin vivoexposure for PTSD. A preliminary open trial had mixed results. More work is needed to support its efficacy.

Brady and colleagues’ (Brady, Dansky, Back, Foa, & Carroll, 2001; Coffey, Schumacher, Brimo, & Brady, 2005) concurrent treatment of PTSD and cocaine dependence combines imaginal andin vivo exposure therapy for PTSD adapted from Foa’s prolonged exposure therapy (Foa & Rothbaum, 1998) with cognitive-behavioral relapse prevention techniques. The manualized treatment includes 16 individual 90-minute sessions including six to nine sessions that include imaginal exposure. Improvements reported in PTSD and cocaine use were maintained at a 6-month follow-up, suggesting that exacerbation of substance use does not necessarily occur following exposure therapy. Coffey et al. (2005) provided recommendations regarding which clients are most likely to benefit from exposure therapy as well as when caution is justified.

SOME PROMISING DEVELOPMENTS AND CHALLENGES FOR THE FUTURE

For there to be meaningful change in the way PTSD/SUD is treated there must be leadership from the highest levels of administration within the VA. In recent years that leadership has been forthcoming as evidenced by the following new policies issued by VA’s headquarters in Washington, D.C. Collectively they hold great promise for improved treatment for our newest, OEF/OIF, PTSD/SUD Veterans.

In June 2004, the Veterans Administration issued a national directive to initiate the Afghan and Iraq Post-Deployment Screen to detect symptoms of PTSD, depression, and high-risk alcohol use among OEF/OIF Veterans seeking VA health care. Seal et al. (2008) reported that Veterans who

screened positive were far more likely than Veterans who screened negative or who were not screened at all to attend follow-up mental health appointments within 90 days of screening leading them to conclude that ‘‘VA screens may help overcome a ‘don’t ask; don’t tell’ climate that surrounds stigmatized mental illness.’’

In November 2007 a memorandum (Deputy Under Secretary of Health for Operations and Management, November 23, 2007) provided the following guidance on the management of patients awaiting admission to inpatient, residential, or other specialized treatment or rehabilitation programs: ‘‘Patients should not be denied admission or have admission delayed based solely upon length of current abstinence from alcohol and/or non-prescribed controlled substances, the number of previous treatment episodes, the time interval since the last residential admission, the use of prescribed controlled substances and/or legal history’’ (p. 6).

In June of 2008 the Department of Veterans Affairs distributed a new Veterans Health Administration Handbook (Veterans Health Administration, June 2008) specifying mental health services to be made available to all veterans. The directives contained in this document will have long-lasting beneficial effects for PTSD/SUD sufferers including (1) ‘‘All patients identified with alcohol use in excess of National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism guidelines need to receive education about drinking limits and the adverse consequences of heavy drinking. Additionally, they should receive brief motivational counseling by a health care worker with appropriate training in this area’’ (p. 20); (2) ‘‘Motivational counseling needs to be available to patients in all settings to support the initiation of (substance abuse) treatment’’ (p. 21); (3) ‘‘All veterans with PTSD must have access to Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) or Prolonged Exposure Therapy (CBT)’’ (p. 29); and (4) ‘‘VA medical centers must have integrated mental health services that operate in their primary care clinic on a full-time basis’’ (p. 33), which will result in shorter wait times for veterans seeking help for mental health problems.

The Department of Veterans’ Affairs has recently increased staffing to treat the expected ‘‘epidemic of mental health disorders’’ among OEF/OIF veterans that Seal and colleagues (Seal, Bertenthal, Miner, Sen, & Marmar, 2007; Seal et al., 2008) forecast. In the past 2 years positions for Suicide Prevention Coordinators and Recovery Coordinators have been created at all VA Medical Centers, as well as new positions for PTSD therapists and psychologists with expertise in PTSD and substance abuse treatment at many centers. Finally the SAMHSA launched a national awareness public service announcement campaign in December 2007 designed to decrease negative attitudes toward mental illness. SAMHSA has published a resource guide titled ‘‘Developing a Stigma Reduction Initiative’’ that can be ordered by phone at (800) 789–2647. These initiatives along with the policy develop-ments have already contributed to needed changes in how we treat OEF/OIF

veterans with PTSD/SUD and bode well for continued improvement in the future.

Implementing evidence-based practices presents challenges, such as overcoming resistance to change, the need for training and organizational changes. Another challenge regarding implementation is the fact that available evidence-based practices do not necessarily apply to the full spectrum of co-occurring disorders that may accompany PTSD other than substance abuse, including, notably, depression, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, chronic pain, and traumatic brain injury (TBI). Recognizing these obstacles to implementing evidence-based programs for persons with co-occurring disorders, SAMHSA’s Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (2006) advocates, ‘‘for the foreseeable future, the clinician will need to use evidence-based thinking to determine the optimal course of action for each patient. . . . Inputs to evidence-based thinking include research, theory, practice principles, practice guidelines, and clinical experience’’ (p. 4). Accordingly, when it is not possible to implement an evidence-based integrated program, specialized PTSD programs should add evidence-based elements from traditional substance abuse programs such as motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2002) and substance abuse treatment programs should consider adding evidenced-based individual treatment for PTSD, such as cognitive processing therapy (Monson & Fredman, 2008), prolonged exposure therapy (Foa et al., 2005), eye movement desensitization reprocessing (Shapiro, 1996), or imaginal rehearsal therapy for nightmares (Krakow et al., 2001; Krakow & Zadra, 2006).

THE CHALLENGE OF ENGAGING AND RETAINING YOUNGER VETERANS IN TREATMENT

More than one half (54%) of OEF/OIF Veterans seen at VA health care facilities are younger than 30 years old, and one half of that group are between the ages of 18 and 24 (Seal et al., 2007). Thirteen percent of the 103,788 OEF/OIF Veterans who enrolled for treatment with the VA between 2001 and 2005 received a diagnosis of PTSD, and 5% received a diagnosis of SUD (Seal et al., 2007). Age was the only demographic that yielded a significant difference, with 18- to 24-year-olds being at greater risk for receiving mental health or PTSD diagnoses compared with Veterans 40 years or older. According to the National Survey of Drug and Health (SAMSHA, 2007) conducted between 2004 and 2006, the youngest group of Veterans are at much greater risk for serious psychological distress (SPD), SUD, and co-occurring SPD and SUD than older Veterans.

As OEF/OIF Veterans seek mental health services in greater numbers, it is necessary to adapt treatment strategies to meet their needs. OEF/OIF

Veterans in their 20s and 30s face challenges that are unique and quite different from those facing older Vietnam Veterans, even though they may carry the same diagnoses. Unlike the Vietnam Veterans currently in treatment, who have been out of the military for 30 years or more, OEF/ OIF Veterans, having returned home from combat relatively recently, face the difficult challenge of adjusting from military to civilian life. Younger Veterans face very different developmental challenges than older Veterans. They must figure out what they want to do with their lives in terms of education, career, and starting a family. In addition, they must begin to differentiate from their families of origin while they remain dependent on them for emotional and in some cases financial support.

Compared to the current Vietnam-era Veteran, who has typically been married (and in some cases divorced) at least once, and is nearing retirement age, OEF/OIF Veterans are typically either looking for a date or in the early stages of a relationship or marriage, and trying to figure out what kind of work they are best suited for. If they are parents, the children are generally preschool age compared to Vietnam-era Veterans, who have been in the empty nest for some time already. Unlike Vietnam-era Veterans, they are most likely entering treatment for the first time, have fewer significant medical issues, and are highly mobile. Access to the Internet, computer games, and high technology has resulted in their having reduced ability to delay gratification (Owen, 2008). Younger veterans want one-stop shopping and quick and easy access to care and become frustrated when they are faced with a complex system of care that was not designed with those needs in mind. For this reason, VA Medical Centers have recently created positions for case managers of OEF/OIF Veterans at every medical center to assist these veterans in navigating through the maze of services offered with the expected result of higher rates of their participation in mental health treatment.

To engage and retain OEF/OIF Veterans with PTSD/SUD in treatment, we need to not only assess for the presence of psychiatric and substance abuse disorders, but also identify and address life stage struggles. We must listen empathically to what is important to them and link treatment directly to their life goals. By offering choices regarding treatment we will accommodate their need to gain greater control over their lives. Choices might include specialized versus integrated treatment, which of several PTSD treatment approaches they prefer (e.g., CPT, ACT, or PE), and abstinence-based versus harm reduction substance abuse treatment. We also need to be flexible regarding when and where treatment can take place. If we want to engage veterans who work during the day, we need to offer evening hours. Another important difference between older and younger Veterans has to do with the fact that the social life of young adults in the United States, particularly males, tends to revolve around drinking. Sixty-four percent of 21- to 25-year-olds drink, and the percentage for 26- to 34-year-olds is only

slightly lower at 60%. Twenty-one percent of young males 18 to 25 years old admit to heavy drinking and 22% to illicit drug use (Owen, 2008). These facts make it easy for OEF/OIF Veterans facing postdeployment stress and wanting to ‘‘fit in’’ to indulge in alcohol or drug use. The fact that drinking is rampant among their peer group makes it difficult for them as well as for mental health professionals to determine when they have crossed the line from social drinking to abuse. According to a recent study 25% of Veterans aged 18 to 25 meet criteria for an SUD (SAMSHA, 2007). For those who are willing to engage in a 28-day intensive outpatient program with the goal of achieving and maintaining sobriety, there are existing programs to address their needs.

For those who are unwilling to commit to an intensive ‘‘substance abuse’’ treatment program upon entering the system, we must find other ways to engage them in services while continuing to assess the impact of their substance use and, if applicable, building motivation for treatment targeting their substance use. We need to offer alternative treatments for OEF/OIF Veterans who are not ready to embrace traditional abstinence-based treatment. Although they are not motivated to quit drinking or using street drugs entirely, they may be motivated to make some changes to reduce the negative consequences of their substance abuse. For example, they may be willing to give up their use of drugs while continuing to drink or to cut back on their drinking. To better accommodate the needs of these Veterans, mental health and substance abuse treatment providers should consider a harm reduction approach advocated by Marlatt and colleagues (Marlatt, 2001; Marlatt & Witkiewitz, 2003). For Veterans who are at the precontemplation or contemplation stages identified by Prochaska and DiClemente (1984) regarding their drinking and/or drug use, a motivational interviewing approach described by Miller and Rollnick (2002) is recom-mended. We can greatly decrease dropout rates by offering Veterans who are ambivalent about change a motivational enhancement group or individual therapy with a professional trained in motivational interviewing. Najavits et al. (2009) have made several accommodations to their finding that men are more difficult to engage in groups initially than women. They offer men an opportunity to sit in on a few sessions of Seeking Safety, after which they can decide if they want to join. Another strategy they have adopted is to conduct an orientation group in a lecture format covering a few key topics, following which participants are invited to join a Seeking Safety group. They do not insist that men commit up front to a specific number of sessions and call treatment ‘‘training’’ to help overcome resistance to the idea of treatment. In addition to these measures, OEF/OIF Veterans may be more likely to participate in groups where age peers are well represented (Owen, 2008).

Because PTSD and substance abuse adversely affect relationships, it is important to involve partners and/or parents in treatment. This can increase

the likelihood that Veterans will remain in treatment. The finding that ‘‘partner burden’’ caused by PTSD can in turn adversely affect the course of treatment for the partner with PTSD (Tarrier, Sommerfield, & Pilgrim, 1999) provides further justification for including the PTSD Veteran’s partner in treatment. McNulty (2008) has opined that better understanding of the deployment and post-deployment stressors that families experience, and the positive affect that resiliency factors can have, will help treatment providers minimize the harmful psychological effects of war on families. Several authors have described couples treatment for PTSD. Monson and Fredman (2008) employed a cognitive-behavioral approach with OEF/OIF Veterans. Basham (2008) utilizes a multimodal, phase-oriented model based on a combination of social and psychological theories including notably attachment theory. Rotunda, O’Farrell, Murphy, and Babey (2008) reported equally good results in applying behavioral couples therapy to couples in which the veteran partner was dually diagnosed with PTSD and an SUD as to couples in which the Veteran had an SUD only.

A vignette is included here to illustrate the challenge of engaging PTSD/ SUD Vets in therapy which addresses their psychiatric and substance abuse issues. The material is based on an actual recent case at the VA Medical Center where the author is employed. Several details were altered to protect the confidentiality of the client.

Carl, a 28-year-old single, White, Iraq and Afghanistan War Veteran, presented himself for treatment 2 years after returning from Iraq. He was living with his parents while attending a local community college. On his initial visit to our Primary Care Mental Health (PMHC) Clinic he was screened by a psychology technician, himself an Iraq War Veteran. Carl had recently dropped several of his college courses due to symptoms of depression including feelings of hopelessness, loss of interest, sleep and appetite disturbance, and passive suicidal ideation. He also screened positive for PTSD and alcohol abuse. He acknowledged drinking a six pack or more daily, smoking marijuana occasionally, and overeating. He had been given a General Discharge from the military due to repeatedly testing positive for marijuana. After meeting with the psychology technician, Carl was seen by the PMHC psychiatrist, who prescribed an antidepressant medication and a nonaddictive sleeping medication, recommended that he cut down on his drinking, and gave him information regarding the suicide prevention hotline. He was then introduced to an OEF/OIF case manager, who offered to help him with several administrative problems including information related to benefits he was eligible for and steps he could take to upgrade his discharge to Honorable. On his second visit with the PMHC psychiatrist 3 weeks later, Carl’s response to the medications was evaluated and changes made accordingly. At that time he agreed to see a psychotherapist and was referred to the psychologist specializing in PTSD/SUD. During her initial meeting with Carl the psychologist established rapport and further evaluated his

depression, PTSD, and substance abuse. He endorsed various PTSD symptoms (including nightmares, intrusive thoughts, avoiding discussion of traumatic events, physiological arousal when reminded of events, angry outbursts, irritability, and feeling numb and detached from others) and drinking five to six beers daily plus shots of hard alcohol twice per week. He expressed the view that if he got help for his depression, his drinking would not be a problem. In his second session he acknowledged that his daily drinking might be contributing to his depressed mood but stated ‘‘I don’t know what else to do.’’ He was encouraged to conduct an ‘‘experiment’’ to not drink for one week and see how it affected his mood. On his third session he stated that he had not drank for the week but had resumed drinking. He admitted to feeling worse when he got up in the morning after drinking the previous evening and being unmotivated to do anything. Pros and cons of continued drinking were discussed as a way to continue to draw out the ambivalence. The therapist provided information about the interrelationship among depression, PTSD, and substance abuse and suggested that he set a realistic goal regarding cutting down on his drinking. He was willing to commit to not drinking for 4 days during the coming week. In his fourth session he reported that he had been successful in achieving his goal regarding drinking but admitted to purchasing marijuana, which he had not used for several months. He expressed concern about his substituting marijuana for alcohol but was ambivalent about abstaining from both substances. He was challenged to be abstinent from both for the next few days to see if he was able to do it and how he felt about it. Carl agreed that if he was unable to meet his own goals regarding his use of alcohol and marijuana that he would consider attending the substance abuse treatment program, supplemented by a twice weekly group for veterans who are dually diagnosed with PTSD and SUDs. Future treatment will utilize motivational interviewing techniques and ACT to help Carl address his avoidance and commit to chosen values.

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS WITH EXAMPLES OF THEIR APPLICATION

The following is a summary of the author’s recommendations for increased success for engaging and retaining OEF/OIF Veterans with PTSD/SUD in treatment:

1. Make treatment easily accessible with a minimum of red tape and delays. When possible offer evening hours to accommodate those clients who are unable to make daytime appointments due to their work schedule.

An OEF/OIF Veteran’s first contact with the VA is generally with a primary care provider (PCP) (Seal et al., 2008). At our facility, if the PCP identifies the need to be evaluated by a mental health provider, that is

accomplished the same day through our Primary Care Mental Health Clinic (PMHC), modeled after the White River Junction VA’s model (Pomerantz, Cole, Watts, & Weeks, 2008). There he or she will be screened for a wide range of potential problems including PTSD, substance abuse, depression, anxiety, TBI, and relationship problems. He will meet with a prescriber and if indicated will leave with a prescription and instructions regarding follow-up. He may also be assigned a case manager and meet with her the same day. OEF/OIF Veterans are informed about an ongoing evening walk-in group to address post-deployment adjustment issues. Because the PMHC is located within a medical clinic, the potential stigma associated with initiating mental health treatment is avoided. The veteran can be seen several times in our PMHC while he is waiting for an initial appointment in the Mental Health Clinic.

2. During initial sessions use ‘‘people skills’’ to good advantage to make the veteran feel welcomed and comfortable.

Listening empathically to struggles with post-deployment adjustment, family, friend and intimate relationships, work, housing and any other issues that are important to the client facilitates ‘‘joining’’ and builds trust. A phone call prior to an initial session and following a ‘‘no-show’’ or a particularly difficult session goes a long way toward communicating caring.

3. Consider ways to overcome resistances to being in therapy by discussing them openly, involving parents, significant others, and other treatment providers.

The writer routinely invites clients to bring their girlfriend or parent(s) with them to a treatment planning session with the goals of providing them with information about PTSD and the recommended treatment and to elicit their support for the client to follow through with therapy.

4. Offer choices regarding treatment modalities and include the Veteran in treatment planning by providing informed consent. When indicated, Veterans should be offered conjoint therapy to address relationship problems in addition to several types of individual and group treatment. After joining with a client and completing the initial assessment, the author generally provides a capsule summary of several alternative ways that he is prepared to work with the client including CPT, ACT, conjoint therapy, or anger management. The client is then given an opportunity to ask questions and express his feeling about which approach fits him best. If the author feels other specific interventions may be warranted (e.g., eye movement desensitization reprocessing or nightmare therapy) or the Veteran inquires about such, he is referred accordingly. A treatment plan identifying symptom reduction as a means of reducing obstacles to specific life goals is then discussed and agreed upon.

5. Offer integrated treatments that address PTSD and substance abuse in the same program rather than requiring extended periods of sobriety as a requirement for entering PTSD treatment. Include in such programming education regarding the reciprocal relationship between PTSD and substance abuse, training on relapse prevention and coping skills to deal with triggers to drink or use illicit drugs, along with treatment specifically targeting PTSD symptoms.

At our facility the PTSD/SUD psychologist leads a group which meets twice per week as a part of the inpatient PTSD program for all participants who have been identified as having a substance abuse diagnosis. The group provides education, coping skills, and an opportunity for participants to explore their own situation. A second group called ‘‘Problem Area Review’’ promotes discussion of a wide range of problems other than PTSD and is conducted along the lines of motivational interviewing principles. A Seeking Safety group is in the planning stage. The requirement of sobriety prior to initiating treat-ment has been eliminated for OEF/OIF Veterans although program participants are required to remain abstinent during the duration of their inpatient stay. If they are unable to accomplish this the treatment team meets to consider which of several options to implement, including referral to the substance abuse treatment program for assessment and treatment, continuation in the program with additional one-on-one counseling regarding their reasons for using, or discharge.

6. Provide cross-training for staff in specialized programs.

One possible way to accomplish this over time would be for staff of one program to provide in-service training on key topics to staff of the ‘‘other’’ program.

At our facility the director of the substance abuse treatment program has provided staff of the inpatient PTSD program with training on motivational interviewing. Another possibility would be for staff members from PTSD and substance abuse programs to sit in on the ‘‘other’’ program for several hours per week. This would not only allow the left hand to know what the right hand is doing but ultimately could result in clinicians in specialized programs providing services previously only available in the ‘‘other’’ program.

7. Meet clients where they are regarding substance abuse issues by employing harm reduction and motivational interviewing as alternatives to abstinence-based programs for Veterans who do not meet criteria for dependency and/or are at lower stages of motivation regarding their use.

Our substance abuse program offers motivational interviewing individually and in groups. The writer attempts to get clients to view their alcohol and/or illicit drug use as one of many possible avoidance strategies which have hindered their recovery from PTSD and to set a

goal regarding future use. When their use interferes with progress in therapy this is pointed out and focused upon until it can be resolved.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

A large number of veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan suffer from PTSD (roughly 11%–19%) and most of those who seek treatment for their PTSD (60%–80%) also meet criteria for substance abuse or dependency. Due to various factors related to the culture of the military, notably the stigma associated with seeking help for mental health issues, only around 40% of those who report significant postdeployment mental health issues receive the help they need. For those veterans with both PTSD and substance abuse who do seek help, their prognosis is poorer than for those with only one or the other disorder. Although VA Medical Centers offer several evidence-based individual therapies for PTSD the date supporting a reduction in substance abuse as a result of participating in these therapies this is lacking at the present. Historically veterans with PTSD/SUD have been required to address their substance abuse issues first in specialized substance abuse treatment programs that do not address their PTSD symptoms. This is problematic as many veterans with long histories of self-medicating for their PTSD either refuse substance abuse treatment or find it impossible to remain abstinent of their drug of choice without receiving help in coping with their PTSD. Several integrated programs have been shown to be effective in treating PTSD/SUD and represent the wave of the future. Recently the Department of Veteran Affairs has initiated policies which hold promise for increasing the number of veterans with PTSD/SUD who receive effective treatment and have access to programs which address PTSD and substance issues concurrently. Younger veterans present special problems which the author describes and offers suggestions for how to successfully engage this group in treatment. Specific recommendations for how to engage and retain OEF/OIF veterans with PTSD/SUD were summarized and examples of how they are being implemented at the author’s VA Medical Center described. The author’s suggestions range from making treatment more user friendly, offering a range of treatment options to accommodate clients with different needs, and ‘‘meeting clients where they are’’ regarding substance abuse issues by employing harm reduction and motivational interviewing. To rise to the challenge of treating this difficult population we must be willing to adapt our treatment to meet their needs rather than requiring them to adapt to therapies that may not be a good fit.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author wishes to thank the following persons who provided valuable input and feedback during the preparation of this manuscript: Kathryn

Basham, Editor, Smith College Studies in Social Work; Nancy Bernardy, National Center for PTSD (NCPTSD), White River Jct., VT; Scott Cornelius, Psychologist, Inpatient PTSD program, Northampton VAMC; Lisa Najavits, National Center for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare System; Ted Olejnik, Suicide Prevention Coordinator, Northampton VAMC; Henry Rivera, Clinical Director, Substance Abuse Treatment Program, Northampton VAMC; and Jennifer Sparrow, PTSD/SUD Psychologist, Northampton VAMC.

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders(4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Back, S. E., Brady, K. T., Jaanimagi, U., & Jackson, J. L. (2006). Cocaine dependence and PTSD: A pilot study of symptom interplay.Addictive Behaviors,31(2), 351– 354.

Back, S. E., Dansky, B. S., Coffey, S. F., Saladin, M. E., Sonne, S., & Brady, K. T. (2000). Cocaine dependence with and without posttraumatic stress disorder: A comparison of substance use, trauma history and psychiatric co-morbidity.

American Journal of Addictions,9(1), 51–62.

Basham, K. (2008). Homecoming as safe haven or the new front: Attachment and detachment in military couples.Clinical Social Work Journal,36, 83–96. Blanchard, E. B., Jones-Alexander, J., Buckley, T. C., & Forneris, C. A. (1996).

Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL).Behavior Research and Therapy,34(8), 669–673.

Brady, K. T., Back, S. E., & Coffey, S. F. (2004). Substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder.Current Directions in Psychological Science,13(5), 206–209. Brady, K. T., Dansky, G. S., Back, S. E., Foa, E. B., & Carroll, K. M. (2001). Exposure

therapy in the treatment of PTSD among cocaine-dependent individual: Preliminary findings.Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment,21, 47–54. Cahill, S. P., Rothbaum, B. O., Resick, P. A., & Follette, V. M. (2009).

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adults. In E. B. Foa, T. M. Keane, M. J. Friedman, & J. A. Cohen (Eds.),Effective treatments for PTSD(2nd ed., pp. 139–222). New York: Guilford Press.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2005). Substance abuse treatment for persons with co-occurring disorders, treatment improvement protocol (TIP) Series 42 (DHHS Publication No. [SMA] 05-3992). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2006).Treatment, volume 1: Understanding evidence-based practices for co-occurring disorders(COCE Overview Paper 6). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and Center for Mental Health Services. Available at: http://coce.samhsa.gov/ cod_resources/PDF/Evidence-BasedPractices(OP6).pdf

Coffey, S. F., Schumacher, J. A., Brimo, M. L., & Brady, K. T. (2005). Exposure therapy for substance abusers with PTSD.Behavior Modification,29, 10–38.

Committee on Gulf War and Health. (2008). Gulf War and health, Volume 6: Physiologic, psychologic, and psychosocial effects of deployment-related stress. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press.

Cook, J. M., Walser, R. D., Kane, V., Ruzek, J. I., & Woody, G. (2006). Dissemination and feasibility of a cognitive-behavioral treatment for substance use disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder in the Veterans Administration. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs,38, 89–92.

Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Operations and Management. (2007, November 23). Memorandum: Management of substance use disorders. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

Desai, R. A., Harpaz-Rotem, I., Najavits, L., & Rosenheck, R. (2008). Seeking Safety therapy: Clarification of results.Psychiatric Services,60(1), 125.

Desai, R., Harpaz-Rotem, I., Rosenheck, R., & Najavits, L. (2009). Treatment of homeless female veterans with psychiatric and substance abuse disorders: Impact of ‘‘Seeking Safety’’ on one-year clinical outcomes.Psychiatric Services,

59, 996–1003.

Donovan, B., Padin-Rivera, E., & Kowaliw, S. (2001). Transcend: Initial outcomes from a posttraumatic stress disorder/substance abuse treatment program.

Journal of Traumatic Stress,14(4), 757–772.

Drake, R. E., Mueser, K. T., Brunette, M. F., & McHugo, G. J. (2004). A review of treatments for people with severe mental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders.Psychiatric Rehabilitation,27(4), 360–374.

Foa, E. B. (1999). Expert consensus guideline series: Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder.Journal of Clinical Psychiatry,60(Suppl. 16), 3–76.

Foa, E. B., Hembree, E. A., Cahill, S. P., Rauch, S. A., Riggs, D. S., Feeny, N. C., et al. (2005). Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: outcome at academic and community clinics.Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,73(5), 953–964.

Foa, E. B., Keane, T. M., Friedman, M. J., & Cohen, J. A. (Eds.). (2009). Effective treatments for PTSD(2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Foa, E. B., & Rothbaum, B. O. (1998). Treating the trauma of rape: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD. New York: Guilford Press.

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes.Behavior Research and Therapy,44(1), 1–25.

Hien, D. A., Nunes, E., Levin, F. R., & Fraser, D. (2000). Posttraumatic stress disorder and short-term outcome in early methadone treatment.Journal of Substance Abuse,19(1), 31–37.

Hoge, C. W., Auchterlonie, J. L., & Milliken, C. S. (2006). Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. Journal of the American Medical Association, 295, 1023–1032. Available at http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/ content/full/295/9/1023

Hoge, C. W., Castro, C. A., Messer, S. C., McGurk, D., Cotting, D. I., & Koffman, R. L. (2004). Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine, 351, 13–22. Available at: http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/351/1/13

Jacobson, I. G., Ryan, M. A. K., Hooper, T. I., Smith, T. C., Amoroso, P. J., Goyko, E. J., et al. (2008). Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems before and after military combat deployment. Journal of the American Medical Association,

300(6), 663–675.

Kofoed, L., Friedman, M. J., & Peck, R. (1993). Alcoholism and drug abuse in patients with PTSD.Psychiatric Quarterly,64(2), 151–171.

Krakow, B., Hollifield, M., Johnston, L., Koss, M., Schrader, R., Warner, T., et al. (2001). Imagery rehearsal therapy for chronic nightmares in sexual assault survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder.Journal of the American Medical Association,286(5), 537–545.

Krakow, B., & Zadra, A. (2006). Clinical management of chronic nightmares: Imagery rehearsal therapy.Behavioral Sleep Medicine,4(1), 45–70.

Marlatt, G. A. (2001). Should abstinence be the goal for alcohol treatment? Negative viewpoint.American Journal of Addictions,10(4), 291–293.

Marlatt, G. A., & Witkiewitz, K. (2003). Harm reduction approaches to alcohol use: Health promotion, prevention, and treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 27, 867–886.

McNulty, P. A. F. (2008, October). Reunification: The silent war of families and returning troops.Federal Practitioner,25, 15–20.

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2002).Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change(2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Milliken, C. S., Auchterlonie, J. L., & Hoge, C. W. (2007). Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. Journal of the American Medical Association,

298(18), 2141–2148.

Monson, C. M., & Fredman, S. J. (2008). Cognitive-behavioral conjoint therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: Application to operation enduring and Iraqi freedom veterans.Journal of Clinical Psychology,64(8), 958–971.

Monson, C. M., & Rizvi, S. L. (2007). Posttraumatic stress disorder. In D. H. Barlow (Ed.),Clinical handbook of psychological disorders(4th ed., pp. 65–122). New York: Guilford Press.

Monson, C. M., Schnurr, P. P., Resick, P. A., Friedman, M. J., Young-Xu, Y., & Stevens, S. P. (2006). Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,74, 898–907.

Mueser, K. T., Noordsy, D. L., Drake, R. E., & Fox, L. (2003).Integrated treatment for dual disorders: A guide to effective practice. New York: Guilford Press. Najavits, L. M. (2002).Seeking Safety: A treatment manual for PTSD and substance

abuse. New York: Guilford Press.

Najavits, L. M., Ryngala, D., Back, S. E., Bolton, E., Mueser, K. T., & Brady, K. T. (2009). Treatment for PTSD and comorbid disorders. In E. B. Foa, T. M. Keane, M. J. Friedman, & J. A. Cohen (Eds.),Effective treatments for PTSD (2nd ed., pp. 508–535). New York: Guilford Press.

Najavits, L. M., Schmitz, M., Gotthardt, S., & Weiss, R. D. (2005). Seeking Safety plus exposure therapy for dual diagnosis men.Journal of Psychoactive Drugs,27, 425–435. Najavits, L. M., Schmitz, M., Johnson, K. M., Smith, C., North, T., Hamilton, N., et al. (2009). Seeking Safety therapy for men: Clinical and research experiences. In

L. J. Kaflin (Ed.) Men and addictions (pp. 37–58). Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

National Center for PTSD (NCPTSD). (n.d.).PTSD and problems with alcohol use. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs. Available at: http://www. ptsd.va.gov/public/pages/ptsd-alcohol-use.asp

Ouimette, P. C., Ahrens, C., Moos, J. W., & Finney, J. W. (1998). During treatment changes in substance abuse patients with posttraumatic stress disorder.Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment,15(6), 555–564.

Ouimette, P. C., Finney, J. W., & Moos, R. H. (1999). Two-year post-treatment functioning and coping of substance abuse patients with posttraumatic stress disorder.Psychology of Addictive Behaviors,13(22), 105–114.

Ouimette, P. C., Moos, R. H., & Finney, J. W. (2003). PTSD treatment and 5-year remission among patients with substance use and posttraumatic stress disorders.Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,71(2), 410–414. Owen, C. L. (2008, May 7). Substance abuse and treatment for young veterans.

Paper presented originally at the Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center at U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Portland, OR, VISN 20. Pomerantz, A., Cole, B. H., Watts, B. V., & Weeks, W. B. (2008). Improving efficiency and access to mental health care: combining integrated care and advanced clinical access.General Hospital Psychiatry,30(6), 546–551.

Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1984). The transtheoretical approach: Crossing traditional boundaries of therapy. Homewood, IL: Dow Jones-Irwin. Pull, C. B. (2009). Current empirical evidence of acceptance and commitment

therapy.Current Opinion in Psychiatry,22(1), 55–60.

Resick, P. A. (2001). Cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder.

Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy,15(4), 321–329.

Resick, P. A., & Schnicke, M. K. (1992). Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims.Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,60(5), 748–756.

Riggs, D. S., Cahill, D. S., & Foa, E. B. (2006). Prolonged exposure treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. In V. M. Follette & J. I. Ruzek (Eds.), Cognitive behavioral therapies for trauma(2nd ed., pp. 65–96). New York: Guilford Press. Rotunda, R. J., O’Farrell, T. J., Murphy, M., & Babey, S. H. (2008). Behavioral couples therapy for comorbid substance use disorders and combat-related posttrau-matic stress disorder among male veterans: An initial evaluation. Addictive Behaviors,33, 180–187.

Seal, K. H., Bertenthal, D., Maguen, S., Gima, K., Chhu, A., & Marmar, C. R. (2008). Getting beyond ‘‘Don’t ask; Don’t tell’’: An evaluation of US Veterans Administration postdeployment mental health screening of veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. American Journal of Public Health,

98(4), 714–720.

Seal, K. H., Bertenthal, D., Miner, C. R., Sen, S., & Marmar, C. (2007). Bringing the war back home: Mental health disorders among 103,788 US veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan seen at Department of Veterans Affairs facilities.

Archives of Internal Medicine,167(5), 476–482.

Shapiro, F. (1996). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): Evaluation of controlled PTSD research. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry,27(3), 209–218.

Silver, S. M., Rogers, S., & Russell, M. (2008). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) in the treatment of war veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychology,64(8), 947–957.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2007).

National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies. Available at: www.oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/2k7nsduh/ 2k7Results.pdf

Tarrier, N., Sommerfield, C., & Pilgrim, H. (1999). Relatives expressed emotion (EE) and PTSD treatment outcome.Psychological Medicine,29(4), 801–811. Triffleman, E., Carroll, K., & Kellogg, S. (1999). Substance dependence

posttrau-matic stress disorder therapy: An integrated cognitive-behavioral approach.

Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment,17(1/2), 3–14.

Veterans Health Administration. (2008). Uniform mental health services in VA medical centers and clinics.Veterans Health Administration Handbook, 1160.01. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs. Available at: www1.va.gov/ vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID51762

Wagner, A. W., & Linehan, M. M. (2006). Applications of dialectic behavior therapy to posttraumatic stress disorder and related problems. In V. M. Follette & J. I. Ruzek (Eds.),Cognitive-behavioral therapies for trauma(2nd ed., pp. 117– 146). New York: Guilford Press.

Weaver, C. M., Trafton, J. A., Walser, R. D., & Kimerling, R. E. (2007). Pilot test of Seeking Safety treatment with male veterans. Psychiatric Services, 58(7), 1012–1013.

Zatzick, D. F., Marmar, C. R., Weiss, D. S., Browner, W. S., Metzler, T. J., Golding, J. M., et al. (1997). Posttraumatic stress disorder and functioning and quality of life outcomes in a nationally represented sample of male Vietnam veterans.

American Journal of Psychiatry,154, 1690–1695.