As therapies and interventions to support critically ill children advance, so does the prevalence of children who survive with multiple conditions and are dependent on technologies (such as home ventilation and enteral feedings) for daily function and quality of life. This population (called “children with medical complexity”1) requires the expertise of pediatric specialists and children’s hospitals but may lack primary care to provide preventive, acute, and chronic care

management (CCM) over their life span.2 The etiologies of their medical complexities are heterogeneous, so knowing the population, regularly assessing and addressing their gaps in care, and coordinating with their medical community and suppliers are essential.

Outpatient pediatric primary care is oriented to services for healthy, typically developing children with episodic illness. Children with

Quality Improvement Strategies

for Population Management of

Children With Medical Complexity

Jennifer Lail, MD, FAAP, a Elise Fields, MBA, b Pamela J. Schoettker, MSaBACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES: Children with medical complexity require the expertise of specialists and hospitals but may lack primary care to provide preventive, acute, and chronic care management. The Complex Care Center (CCC) at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center employed quality improvement methodologies in 3 initiatives to improve care for this fragile population.

METHODS: Improvement activities focused on 3 main areas: population identification and stratification for care support, reliable delivery of preventive and chronic care, and planned care to identify and coordinate needed services.

RESULTS: The percent of patients who attended a well-child care visit in the previous 13 months increased 91% and was sustained for the next year. The median monthly no-show rate remained unchanged. Within 10 months of implementing the interventions, >90% of CCC patients <7 years of age were receiving all recommended vaccines. Seventy-two percent of all CCC patients received their annual influenza vaccine. A sustained 98% to 100% of children with a complex chronic disease received previsit planning (PVP) for their well-child care and chronic condition management visits, whereas only 1 new patient did not receive PVP.

CONCLUSIONS: Children with medical complexity require adaptations to typical primary care processes to support preventive health practices, chronic and acute care management, immunization, and collaborative care with their multiple specialists and support providers. We used quality improvement methodology to identify patients with the highest needs, reliably deliver appropriate preventive and chronic care, and implement PVP.

abstract

To cite: Lail J, Fields E, Schoettker PJ. Quality Improvement Strategies for Population Man agement of Children With Medical Complexity. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20170484

aJames M. Anderson Center for Health Systems Excellence

and bDivision of General and Community Pediatrics,

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio

Dr Lail led the project, participated in its design, led the application of quality improvement methodologies, helped to draft the original manuscript, and contributed to its critical revision; Ms Fields participated in the design of the project, completed data collection, data analysis, and data interpretation, helped to draft the original manuscript, and contributed to its critical revision; and Ms Schoettker helped to draft the original manuscript and contributed to its critical revision; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

DOI: https:// doi. org/ 10. 1542/ peds. 2017 0484 Accepted for publication May 3, 2017

Address correspondence to Jennifer Lail, MD, FAAP, Clinical Pediatrics, Complex Care Center, James M. Anderson Center for Health Systems Excellence, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave, Mail Location 7014, Cincinnati, OH 45229. Email: jennifer.lail@cchmc.org

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 00314005; Online, 10984275).

Copyright © 2017 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: No external funding.

multiple chronic conditions require longer appointments, bidirectional communication with specialists, and management of complicated medication, equipment, and therapy regimens within a care plan. In 2012, 43% of responding primary care pediatricians endorsed subspecialty care as the best source of a medical home for children with complex or rare conditions and cited time and cost as barriers to caring for these children in their practices.3 Outpatient primary care programs for children with medical complexity are emerging to meet these unique needs, and they provide collaboration and care coordination with specialists and the community and serve as the medical home.4–8 Nonetheless, a recent study by Berry et al2 found that 40% of children with medical complexity did not have an annual primary care visit, although they may have had inpatient hospitalizations, procedures, and emergency department (ED) visits. Baseline data collected from patients who were treated at the Complex Care Center (CCC) at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) showed that only 48% had received a well-child care (WCC) visit in the previous 13 months. As a result, CCC clinicians and frontline staff used quality improvement (QI) methodologies in 3 practice-transformation initiatives to standardize processes, increase reliable preventive care, and support planning and care coordination for this fragile population. The CCC team saw regular, templated WCC encounters (including CCM) as an opportunity to both deliver preventive care and identify and support the closure of care gaps.

PATIENTS AND METhODS Setting

CCHMC is a large, urban, pediatric, academic medical center. The CCC, in the Division of General and

Community Pediatrics, serves as the primary care medical home for 457 children with medical complexity. Nine clinical sessions are held weekly, and a medical provider (a physician or nurse practitioner) is on call 24 hours per day. The CCC helps families coordinate their extensive network of home care equipment, nursing, and supply services. Patients eligible for CCC meet at least 1 of 3 criteria: they are dependent on some item of technology to stay alive, 9 have ≥3 chronic medical conditions, or need access to ≥3 major-organ–system specialists. Seventy-two percent of patients are Medicaid-insured, and 35% have alternative state-based funding through Medicaid or a waiver. The 2 clinic locations employ 4 physicians and 1 nurse practitioner (a total of 3.3 full-time equivalents [FTEs]). The support teams consist of 2.0 FTE social workers, 1.5 FTE dieticians, 3.0 FTE registered nurse care managers, 3.8 FTE registered nurses, 1.2 FTE medical assistants, and 2.6 FTE administrative team members. Their leadership group includes a medical director, clinical nurse manager, and business manager, with input on strategy from a pediatrician trained in QI. QI strategies are taught and implemented as part of ongoing staff education.

human Subjects Protection The CCHMC Institutional Review Board determined that this project did not meet the regulatory criteria for research involving human subjects and that ongoing oversight was not required.

Planning the Intervention

Different members of the CCC team worked on the 3 initiatives and were led by a medical provider, a nurse, and/or a business manager. CCHMC QI consultants, data analysts, and experts on the CCHMC electronic medical record (EMR) provided additional support as needed.

The separate teams used similar strategies of current state analysis with baseline data collection, process mapping, creation of a key driver diagram, consensus building and team education, role optimization for tasks, and standardization of processes and documentation. Improvement was supported by repeated series of plan-do-study-act cycles, 10 weekly data feedback, and investigation of failures.

Improvement Activities

During the planning stage, 3 main areas were prioritized as needing improvement to standardize preventive care processes for high reliability.11

Identifying and Defining the Population for Improved Management

activation, care gap reporting, and care team identification were built into the registry to permit data retrieval to support daily care and population management.

Delivering Preventive and Chronic Care Reliably

CCC staff also mapped the patient-scheduling process, standardized visit types, and defined appropriate intervals for face-to-face outpatient encounters by using the American Academy of Pediatrics’s Bright Futures Guidelines for preventive care standards.14 This work identified the need for both WCC and semiannual CCM encounters to support reliable care delivery for such medical complexity.

CCC team members reviewed coding practices and educated staff and families with written, updated standards of care through weekly staff meetings, a patient newsletter, and personal interactions.

Completion of WCC and CCM visits were linked to medication refills and state-mandated care plans to promote adherence. Staff scheduled follow-up visits before the family left the clinic and established monthly outreach calls to schedule routine visits. Administrative and clinical staff developed electronic tracking formats to prompt needed visits. Families who missed appointments were called to inquire about the child’s safety and reschedule. Daily morning huddles by providers, care managers, dieticians, and social workers allowed for previsit planning (PVP) (more below). A templated chart review before visits promoted collaboration with families to identify and close gaps in care and assess unmet dietary and psychosocial needs.

Missed immunizations are common in this population because of medical contraindications and frequent and protracted hospitalizations. A CCC provider and nurse led a workgroup to ensure all eligible vaccines were

given by adapting the timeline for immunization completion to age 7 years. They used failure modes and effects analysis15 (a systematic approach to anticipate what could go wrong with a process and how to take corrective actions to prevent failure) to identify opportunities for improvement, which included previsit immunization reviews by nursing staff, clinic huddles to highlight needed immunizations, and coding education to document and retrieve vaccine refusals.

Stickers were applied to clinic computers to prompt vaccine discussions and identify billing codes to indicate a declined vaccination. Medical assistants reviewed charts before clinic huddles to identify which vaccines were needed for scheduled patients. Weekly data that were reported at a provider-specific level prompted remediation for missed vaccines or improper coding and again underscored the importance of vaccine completion for this high-risk population.

Similar surveillance and remediation processes for vaccines were applied to CCHMC’s annual influenza vaccine initiative in 2015 and 2016. In addition, an electronic prompt was posted in the EMR, and standing orders allowed staff to pend the order for an influenza vaccine. In the fall of 2015 and 2016, CCC staff made outreach calls to the families of all patients whose influenza vaccine was not documented in the EMR to offer nurse visits, vaccine kiosks, and vaccines given at specialty encounters.

Planning and Coordinating Care With Specialists

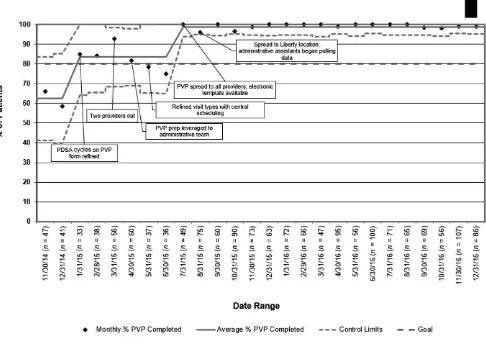

Because these patients see ≥3 specialists, they require meticulous PVP to identify all health care services received since the last visit. As part of a 6-month QI training project, 16 1 CCC physician worked with care managers to map the process for previsit preparation,

identify necessary interventions (Fig 1), and build and test a paper PVP tool. During plan-do-study-act cycles, the lead physician, business manager, and nurse care managers identified and analyzed process failures. Eventually, rapid-cycle testing was spread to all providers to refine the core elements and format of the PVP tool. The resulting standard PVP tool collected a review of interim ED visits and/or hospitalizations, gaps in needed care, specialty consult visits, procedures, vaccines, imaging studies, and laboratory tests that were used to inform a WCC or CCM visit. After establishing high reliability11 with nonelectronic processes, the CCC team worked with EMR experts to build an electronic PVP note that allowed autopopulation of some of the desired elements, could be incorporated into encounter documentation, and informed the after-visit summary.

In November 2015, the

administrative team was trained to identify assessments and plans from interim encounters with specialists in the child’s electronic record and copy them into this PVP template. Recent laboratory tests, imaging, and ED visits were also electronically incorporated. Providers then reviewed the template, synthesized and summarized consultant recommendations, and identified gaps in care. Patient needs, tests, vaccines, procedures, and specialty follow-up identified during PVP were addressed during the visit and included in the after-visit summary for follow-up.

Measures

of patients who had had a WCC visit in the previous 13 months; the percent of patients aged 0 to 7 years that had received all recommended vaccinations for which they were eligible17; the percent of all patients who had received their annual influenza vaccine; and the percent of patients who met the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm definition of children with a complex chronic disease12 who had PVP for their WCC and CCM visits.

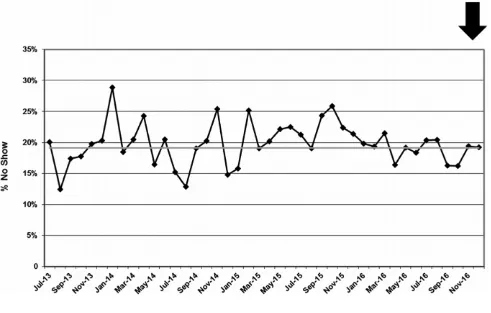

The CCC monthly no-show rate, which was defined as the percent of patients who did not come to their appointment or canceled within 24 hours of their scheduled

appointment, was monitored as a balancing measure to the WCC outreach measure to ensure that improvement activities did not create a disruption in other areas of the system. The percent of PVP that was completed for new patient visits was monitored to ensure that expanding PVP to WCC and/or CCM visits did not erode the existing high levels of PVP for new patients.

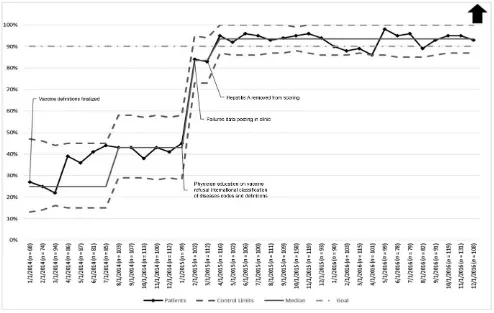

Data Collection and Analysis Baseline data were collected before starting 3 of the improvement interventions. The baseline period for the WCC outreach project was July 1, 2013–June 30, 2014, and the study

period was July 1, 2014–December 31, 2016. The baseline period for the standard childhood immunizations project was January 1, 2014– February 28, 2014, and the study period was March 1, 2014–December 31, 2016. The baseline period for the PVP project was November 1, 2014–December 31, 2014, and the study period was January 1, 2015– December 31, 2016. Baseline annual influenza vaccine administration data were not available for the CCC population; the study period was from September to December of 2015 and 2016. Run charts and statistical process control charts18–20 were used to track changes in outcomes over

FIGURE 1

time. Standard industry criteria (8 consecutive points above or below established centerline, 6 consecutive rising or falling points, or points outside control limits) were used to distinguish random, common cause variation from significant, special cause change attributable to the interventions.18–20

RESULTS

Delivering Preventive and Chronic Care Reliably

The percent of active patients who attended a WCC visit in the previous 13 months increased from an average of 47.8% at baseline to 91.3%, an increase of 91%, by December 2015 and was sustained for the next year (Fig 2). The median monthly no-show rate remained unchanged (Fig 3).

At baseline, only 28% of CCC patients <7 years of age received all of the recommended vaccines for which they were eligible. Within 10 months of implementing the interventions, this value exceeded the 90% goal established by the team and was sustained for the next 21 months (Fig 4). Seventy-two percent of all CCC patients in 2015 and 2016 received their annual influenza vaccine, 6% refused the vaccine, the vaccine was contraindicated for 1% of patients, and 21% were unable to be contacted.

Planning and Coordinating Care With Specialists

During the baseline period, when templates and PVP processes were under development, a mean of 62% of patients meeting the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm definition of children with a complex

chronic disease12 received PVP for their WCC and CCM visits. During the 6-month intervention period, the established goal of 80% completion was achieved. After the implementation of electronic templates and administrative support to facilitate the spread of PVP to all providers at both sites, the completion rate was sustained at 98% to 100% (Fig 5). Expanding PVP to WCC and CCM visits had no deleterious effect on PVP for new patient visits. Only 1 new patient did not receive PVP during the study period.

DISCUSSION

The growing population of children with medical complexity and technological dependence requires adaptations to typical primary care processes and collaborative care

FIGURE 2

with their multiple specialists and support providers. Although children with medical complexity need recommended health maintenance services and screenings, their complex medication schedules, input from specialists, and medical instability may supersede needed preventive care. QI strategies that have been found to be effective in such practice transformation include the application of policies, procedures, and processes to deliver organized, evidence-based, and coordinated care, guided by a population registry.21, 22

Although CCHMC provided support for our project through access to internal QI and information technology experts, no new staff

were added to the CCC and no additional funding was provided. The effort was driven by CCC clinicians and frontline staff, who worked to transform and standardize provided care. One CCC pediatrician also simultaneously led a CCHMC strategic plan initiative application of the Chronic Care Model.23–27 The CCC was not a participant in the initiative, but learnings from that initiative (such as targeted interventions for highest needs, timely data feedback, and leveraging work to appropriate team members to enhance provider efficiency28, 29) helped shape the CCC efforts. We also used QI tools and serial tests of change to identify the children most likely to benefit; assess patients’ individual needs; develop

a care plan around their needs and preferences; engage and educate patients, families, and providers; connect patients to appropriate follow-up and support services; coordinate care and facilitate communication among all providers; and monitor progress. The well-child and vaccine initiatives were applied to the entire CCC population, namely children with medical complexity and their siblings. The PVP interventions were directed only to patients who met the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm definition of children with complex chronic disease.12 Because children with medical complexity have varying conditions and different etiologies for their conditions, identifying and

FIGURE 3

risk-stratifying them were critical steps in managing each child’s needs. Simplifying and standardizing visit types and documentation as well as administrative and clinical processes helped all team members to apply their unique skills for the benefit of the child and family. Frequent data feedback with use of Pareto charts30 to identify failures, followed by remedial plan-do-study-act cycles, helped with staff education and drove ongoing improvement and reliability of the processes.

Challenges included staff attrition, finding dedicated time for QI work, and reaching consensus. Leaders committed to standardization and accountability among colleagues and willing to dedicate staff time to improvement were essential. Mapping processes, eliminating unnecessary and duplicative efforts,

and optimizing each staff member’s contributions saved time and made work flow more efficient. Because of such activities, patients completing a WCC visit have increased, reaching 91% in February 2017.

Our study highlighted a primary care (rather than a consultative or comanagement) approach to managing children with medical complexity. A randomized clinical trial of an enhanced medical home for children at high risk in which a dedicated pediatric gastroenterologist, neurologist, and allergist and/or immunologist attended the clinic once a month achieved decreases in both the rate of children with a serious illness and total hospital and clinic costs.31 A program that linked clinics for children with medical complexity at 2 community hospitals with a tertiary care center decreased cost.32

Those clinics were staffed by local community pediatricians and a nurse practitioner associated with the tertiary care center. Both parents and providers considered the ability to receive care close to the patient’s home as a key benefit.

Generalization of our results is limited by setting the interventions in a tertiary children’s hospital clinic for children with medical complexity. The fact that CCC patients are comanaged principally by pediatric specialists within CCHMC, with a shared medical record, certainly facilitated

implementation. Social service, care management, and nutrition support for WCC may not be present in other settings. Also, we did not measure patient, family, or staff satisfaction with the changes made. Information systems and data analytic support for this work were valuable, but all

FIGURE 4

processes, tools, and data collection were developed by CCC clinicians and frontline staff, were first tested in nonelectronic formats, and could be applied in a less-resourced setting. Initial concern about family objection to required WCC visits was not confirmed in the implementation. Leadership changes and staff attrition challenged the work, and evolving federal and state funding models for children with medical complexity will likely impact clinic operational infrastructure.

CONCLUSIONS

We used QI methodologies to identify patients with the highest needs, reliably deliver appropriate

preventive and chronic care, and implement PVP. Providers willingly applied standards of prepared, proactive care when supported by team-based efforts to standardize care and template documentation. Data collection with regular feedback on process completion drove ongoing improvement and promoted process reliability. The next steps will include work to evaluate the impact of preventive and planned care on clinical and functional outcomes, satisfaction, health care costs, and utilization.

ACkNOWLEDGMENTS

All of the work represented in this article was facilitated by the providers, leadership, and staff of the CCC.

REFERENCES

1. Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, et al. Children with medical complexity: an emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):529–538

2. Berry JG, Hall M, Neff J, et al. Children with medical complexity and Medicaid: AbbREvIATIONS

CCC: Complex Care Center CCHMC: Cincinnati Children’s

Hospital Medical Center CCM: chronic care management ED: emergency department EMR: electronic medical record FTE: full-time equivalent PVP: previsit planning QI: quality improvement WCC: well-child care

FIGURE 5

spending and cost savings. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(12):2199–2206 3. Van Cleave J, Okumura MJ, Swigonski

N, O’Connor KG, Mann M, Lail JL. Medical homes for children with special health care needs: primary care or subspecialty service? Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(4):366–372 4. Berry JG, Agrawal R, Kuo DZ, et al.

Characteristics of hospitalizations for patients who use a structured clinical care program for children with medical complexity. J Pediatr. 2011;159(2):284–290

5. Kuo DZ, Berry JG, Glader L, Morin MJ, Johaningsmeir S, Gordon J. Health services and health care needs fulfilled by structured clinical programs for children with medical complexity.

J Pediatr. 2016;169:291–296.e1 6. Hamilton LJ, Lerner CF, Presson

AP, Klitzner TS. Effects of a medical home program for children with special health care needs on parental perceptions of care in an ethnically diverse patient population. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(3):463–469 7. Lerner CF, Kelly RB, Hamilton LJ, Klitzner

TS. Medical transport of children with complex chronic conditions. Emerg Med Int. 2012;2012:837020

8. Klitzner TS, Rabbitt LA, Chang RK. Benefits of care coordination for children with complex disease: a pilot medical home project in a resident teaching clinic. J Pediatr. 2010;156(6):1006–1010

9. US Congress, Office of Technology Assessment. TechnologyDependent Children: Hospital v. Home care. A Technical Memorandum, OTATMH38. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1987. Available at: http:// ota. fas. org/ reports/ 8728. pdf. Accessed March 21, 2017

10. Langley GJ, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The Improvement Guide. A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. San Francisco, CA: JosseyBass; 1996 11. Luria JW, Muething SE, Schoettker PJ,

Kotagal UR. Reliability science and patient safety. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53(6):1121–1133

12. Simon TD, Cawthon ML, Stanford S, et al; Center of Excellence on Quality of Care Measures for Children With

Complex Needs (COE4CCN) Medical Complexity Working Group. Pediatric medical complexity algorithm: a new method to stratify children by medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6). Available at: www. pediatrics. org/ cgi/ content/ full/ 133/ 6/ e1647

13. Lail J, Schoettker PJ, White DL, Mehta B, Kotagal UR. Applying the chronic care model to improve care and outcomes at a pediatric medical center. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43(3):101–112

14. Hagen JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, eds.

Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 3rd ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008 15. Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

Failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA) tool. Available at: www. ihi. org/ resources/ Pages/ Tools/ FailureModesandEf fectsAnalysisTool . aspx. Accessed February 10, 2017 16. Kaminski GM, Britto MT, Schoettker

PJ, Farber SL, Muething S, Kotagal UR. Developing capable quality improvement leaders. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(11):903–911

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practice (ACIP). Available at: https:// www. cdc. gov/ vaccines/ acip/ index. html. Accessed December 20, 2016

18. Amin SG. Control charts 101: a guide to health care applications. Qual Manag Health Care. 2001;9(3):1–27

19. Benneyan JC, Lloyd RC, Plsek PE. Statistical process control as a tool for research and healthcare improvement. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(6):458–464

20. Provost LP, Murray SK. The Health Care Data Guide: Learning From Data for Improvement. San Francisco, CA: JosseyBass; 2011

21. National Center for Medical Home Implementation. Building your medical home. An introduction to pediatric primary care transformation. Managing your patient population. Available at: https:// medicalhomes. aap. org/ Pages/ Managing Your Patient Population. aspx. Accessed March 21, 2017

22. Wagner EH, Coleman K, Reid RJ, Phillips K, Sugarman JR. Guiding

transformation: how medical practices can become patientcentered medical homes. The Commonwealth Fund. Available at: www. commonwealthfund. org/ ~/ media/ Files/ Publications/ Fund%20 Report/ 2012/ Feb/ 1582_ Wagner_ guiding_ transformation_ patientcentered_ med_ home_ v2. pdf. Accessed March 21, 2017

23. Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1775–1779

24. Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, part 2. JAMA. 2002;288(15):1909–1914

25. Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1(1):2–4

26. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20(6):64–78 27. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511–544

28. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The playbook. What are key elements to redesigning care? Available at: www. bettercareplayboo k. org/ questions/ what are key elements redesigning care. Accessed December 21, 2016 29. Anderson GF, Ballreich J, Bleich S,

et al. Attributes common to programs that successfully treat highneed, high cost individuals. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(11):e597–e600

30. Tague NR. The Quality Toolbox. 2nd ed. Milwaukee, WI: American Society for Quality, Quality Press; 2005

31. Mosquera RA, Avritscher EB, Samuels CL, et al. Effect of an enhanced medical home on serious illness and cost of care among highrisk children with chronic illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(24):2640–2648 32. Cohen E, LacombeDuncan A, Spalding

K, et al. Integrated complex care coordination for children with medical complexity: a mixedmethods evaluation of tertiary carecommunity collaboration.

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2017-0484 originally published online August 29, 2017;

2017;140;

Pediatrics

Jennifer Lail, Elise Fields and Pamela J. Schoettker

Medical Complexity

Quality Improvement Strategies for Population Management of Children With

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/140/3/e20170484

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/140/3/e20170484#BIBL

This article cites 22 articles, 6 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/quality_improvement_

Quality Improvement

_management_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/administration:practice

Administration/Practice Management

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/medical_home_sub

Medical Home

_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/community_pediatrics

Community Pediatrics

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2017-0484 originally published online August 29, 2017;

2017;140;

Pediatrics

Jennifer Lail, Elise Fields and Pamela J. Schoettker

Medical Complexity

Quality Improvement Strategies for Population Management of Children With

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/140/3/e20170484

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.