Sexual Intercourse Among Adolescents Maltreated

Before Age 12: A Prospective Investigation

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: Sexual abuse is a risk factor for early initiation of sexual intercourse. Although other forms of maltreatment may also increase children’s emotional distress, there has been limited attention given to the role of other forms of maltreatment in the initiation of intercourse.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: Our study is one of the first to use a prospective methodology to demonstrate that other forms of maltreatment increase the likelihood of sexual intercourse by 14 and 16 years of age in a high-risk sample.

abstract

OBJECTIVE:To examine whether child maltreatment (physical, emo-tional, and sexual abuse, and neglect) predicts adolescent sexual in-tercourse; whether associations between maltreatment and sexual intercourse are explained by children’s emotional distress, and whether relations among maltreatment, emotional distress, and sex-ual intercourse differ according to gender.

METHODS:The Longitudinal Studies of Child Abuse and Neglect was a multisite, longitudinal investigation. Participants ranged from at-risk to substantiated maltreatment. Maltreatment history was assessed through Child Protective Service records and youth self-report at age 12. Youth reported emotional distress by using the Trauma Symptom Checklist at the age of 12 years and sexual intercourse at ages 14 and 16. Logistic and multiple regressions, adjusting for gender, race, and site, were used to test whether maltreatment predicts sexual intercourse, the explanatory effects of emotional distress, and gender differences.

RESULTS:At ages 14 and 16, maltreatment rates were 79% and 81%, respectively, and sexual initiation rates were 21% and 51%. Maltreatment (all types) significantly predicted sexual intercourse. Maltreated youth re-ported significantly more emotional distress than non-maltreated youth; emotional distress mediated the relationship between maltreatment and intercourse by 14, but not 16. At 14, boys reported higher rates of sexual intercourse than girls and the association between physical abuse and sexual intercourse was not significant for boys.

CONCLUSIONS:Maltreatment (regardless of type) predicts sexual inter-course by 14 and 16. Emotional distress explains the relationship by 14. By 16, other factors likely contribute to intercourse. Maltreated children are at risk for early initiation of sexual intercourse and sexually active adoles-cents should be evaluated for possible maltreatment.Pediatrics2009;124: 941–949

CONTRIBUTORS:Maureen M. Black, PhD,aSarah E. Oberlander, PhD,aTerri Lewis, PhD,bElizabeth D. Knight, MSW,cAdam J. Zolotor, MD, MPH,cAlan J. Litrownik, PhD,d Richard Thompson, PhD,eHoward Dubowitz, MS, MD,aand Diana E. English, PhDf

aDepartment of Pediatrics, University of Maryland School of

Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland;bDepartment of Social Medicine,

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina;

cUniversity of North Carolina Injury Prevention Research Center,

Chapel Hill, North Carolina;dDepartment of Psychology, San

Diego State University, San Diego, California; andeJuvenile

Protective Association, Chicago, Illinois; andfSchool of Social

Work, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington

KEY WORDS

child maltreatment, adolescent sexuality, sexual intercourse, neglect, sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, emotional distress

ABBREVIATIONS

CPS—Child Protective Services

TSC-C—Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children CI— confidence interval

OR— odds ratio

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2008-3836 doi:10.1542/peds.2008-3836

Accepted for publication Mar 2, 2009

Address correspondence to Maureen M. Black, PhD, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, 737 W Lombard St, Room 161, Baltimore, MD 21201. E-mail: mblack@peds.umaryland.edu

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275). Copyright © 2009 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

Sexual intercourse among adolescents increases their risk for inconsistent con-traception and multiple partners,1,2

be-haviors that expose them to sexually transmitted infections and pregnancy.3

Initiation of sexual intercourse begins before the age of 14 years, with lower rates for white (4%) than for black (15%) youth.4,5 Rates of initiation

in-crease throughout adolescence; by 16 to 17 years, 52% of white and 74% of black youth have had intercourse.6

Maltreatment, specifically sexual abuse, is a risk factor for early initiation of intercourse,7 possibly attributed to

maltreatment-related emotional dis-tress. Although other forms of mal-treatment may also increase chil-dren’s emotional distress,8 there has

been limited attention to the role of other forms of maltreatment in the ini-tiation of intercourse.

Gender differences in the link between sexual abuse history and sexualized behavior have been reported. Tarren-Sweeney9reported that maltreated girls

are more likely than boys to display sexualized behaviors. Others have found no gender differences.10,11

How-ever, much of the research has been ret-rospective, potentially confounding sex-ual abuse with consenssex-ual intercourse.

In our investigation we used a prospec-tive design to examine whether maltreat-ment increases the likelihood of sexual intercourse, whether the relationship is explained by children’s emotional distress, and whether there are gender differences. We tested the following 3 hy-potheses: (1) maltreatment is associ-ated with sexual intercourse by the ages of 14 and 16 years, with stronger associ-ations at 14 years, when sexual inter-course is less common4,6; (2) the

associ-ation between maltreatment and sexual intercourse at 14 and 16 years of age is mediated by children’s emotional dis-tress8 (Fig 1); and (3) relations among

maltreatment, emotional distress, and

sexual intercourse are stronger for girls than for boys.9

METHODS

Study Overview

The Longitudinal Studies of Child Abuse and Neglect include a coordinating center and 5 independent prospective longitudinal studies of maltreatment. Participants represent a continuum of maltreatment at recruitment, ranging from being at risk (ie, demographic or medical risk factors of maltreatment) to being subjects with substantiated cases severe enough to warrant placement.12

Sites use common protocols approved by local institutional review boards, in-cluding informed consent.

Children were enrolled at the age of 4 years and followed in face-to-face interviews, as were their caregivers. In-terviews were administered by us-ing an audio computer-assisted self-interviewing system, with information presented visually on a screen and au-rally over headphones.13 Interviews

were conducted at ages 12, 14, and 16 years.* Maltreatment information was collected from Child Protective Ser-vices (CPS) records.

Participants

Two samples of youth with data on maltreatment and emotional distress at 12 years of age are included. One has sexual intercourse data according to age 14 years (n⫽637) and the other by age 16 years (n⫽493); 411 youth are included in both samples. The sam-ples have similar demographics. They are evenly divided by gender (boys: 50.0% in age 14 sample, 49.0% in age 16 sample) and race/ethnicity (black: 54.0% and 52.0%) and have median family income of $20 000 to $24 999, and few live with foster parents (4.3% and 5.7%). Retention from the age of 12 years was 81% and 68%. Attrition anal-yses at 14 and 16 years revealed no dif-ferences in gender, race, or maternal ed-ucation. Adolescents who returned at 16 years of age were slightly older than those who did not (12.55 vs 12.38;P⬍ .01). Attrition varied according to site, from 11% to 28% at 14 years and from 16% to 38% at 16 years.

Measures

Independent Variables

Maltreatment History

Although many investigators use CPS reports to define maltreatment, relying exclusively on reports may in-troduce biases and limit the sample to

*Interviews were designed to be conducted when youth were aged 12, 14, and 16 years. However, their actual ages varied.

Age 14 y Age 16 y <Age 12 y Age 12 y

Emotional distress

Sexual intercourse

Sexual intercourse

History of maltreatment

FIGURE 1

children with problems severe or chronic enough for referral to CPS.14

Conversely, relying exclusively on youth self-report may miss children who have been reported to CPS. Fol-lowing the recommendations of inves-tigators who have examined multiple sources of maltreatment information,8,15

we used both CPS records and youth self-report to determine maltreatment history.

CPS Reports

Maltreatment was assessed via CPS case records, which were abstracted and recoded.16 Interrater reliability

(90%) was established before field en-try and was maintained through anal-yses of a random sample of records across sites (⬎0.70). Maltreatment was defined as a CPS report by the age of 12 years for physical, sexual, or psy-chological abuse or neglect17,18; 63%

and 68% met criteria at ages 14 and 16 years.

Youth Self-report of Maltreatment Project developed measures of self-report of physical, sexual, and psycho-logical abuse, were administered at 12 years to assess lifetime abuse.15

Half of the subjects, 49% at 14 years of age and 50% at 16 years of age, met criteria for abuse.

Maltreatment was defined by either a CPS report or a youth-defined re-port. If either data source was missing and the other indicated no maltreat-ment, the youth was removed from the analysis. Subtypes were not mutually exclusive.

Dependent Variables

Sexual Intercourse

Sexual intercourse was measured at 14 and 16 years by asking, “Have you ever had sex?”19This item was

intro-duced by a statement defining sex as sexual intercourse. Qualitative analy-sis in other samples have indicated that youth interpret this question as indicating vaginal intercourse.20

Emotional Distress

Emotional distress was measured at the age of 12 years by using the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Chil-dren (TSC-C),21a standardized, 54-item

checklist for 8- to 16-year-old children. The child reports the frequency for each item on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (almost all the time). Raw scores are transformed into gender- and age-specifictscores. The scales have excellent internal consistency, reliability, and concur-rent validity (J. Briere, C. B. Lanktree, The Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (TSC-C): Preliminary Psycho-metric Characteristics, unpublished manuscript, 1995).21,22An overall TSC-C

score was created by averaging thet scores for anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, anger, and dissociation. The ␣ values were .93 and .94.

Data Analysis

Adolescent gender, age, race, and re-search site were included as covari-ates. Race was dichotomized into mi-nority and nonmimi-nority (white). Site was collapsed into 2 categories on the basis of recruitment criteria: CPS-documented maltreatment and mix-ture of maltreated, at-risk, and control participants. Family income was en-tered as a covariate and removed be-cause it was not a significant predictor.

The association between maltreat-ment history and sexual intercourse was tested by regressing sexual in-tercourse by age 14 or 16 years on maltreatment history by using logistic regression. The mediating effects of emotional distress were tested by us-ing linear regression23 and

signifi-cance tests of the indirect effect.24

Mediation was considered to occur if the association between maltreat-ment history and sexual intercourse at 14 or 16 years of age was attenuated by emotional distress and if indirect

effects were significant.25Regression

coefficients were standardized26,27 to

allow for significance tests of the in-direct effects.†

To investigate gender moderation, a gender ⫻ maltreatment interaction term was included in all of the analy-ses. Significant interactions were probed to determine the locus of ef-fect.29 All of the analyses were

con-ducted by using SPSS 15 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).30Statistical

sig-nificance was set at aPvalue of⬍.05.

RESULTS

The mean ages of the samples were 14.34 years (SD: 0.42) and 16.32 years (SD: 0.42). Seventy-nine percent at 14 years of age and 81% at 16 years of age had a history of maltreatment by the age of 12 years (Table 1). Rates of mal-treatment subtypes were as follows: 26% and 29% (sexual abuse), 45% and 49% (physical abuse), 59% and 62% (psychological abuse), and 57% and 61% (neglect). Twenty-one percent and 19% of participants at 14 and 16 years had no history of maltreatment and composed the comparison group.

The mean TSC-C scores at 14 and 16 years were 40.81 (SD: 7.27) and 41.08 (SD: 7.93), respectively. Twenty-one percent at 14 years of age and 51% at 16 years of age had engaged in sexual intercourse. At 14 years, boys were more likely to have engaged in sexual intercourse than girls; at 16 years of age, there was no gender difference.

Sexual Abuse and Sexual Intercourse

At the age of 14, youth with a history of sexual abuse were 3.26 times (95%

†The test of the mediated effect was calculated as

follows:z⬘ ␣

冑␣

2S

2⫹2S

␣

2⫹S

␣

2S

2.

25This

meth-od has low power because of the nonnormal distribu-tion of␣and. Therefore, the table of critical values provided by MacKinnon et al28was used to determine

confidence interval [CI]: 1.73– 6.15; P⬍.001) more likely to report sexual intercourse than comparison youth. Youth with a history of sexual abuse had higher TSC-C scores than com-parison youth; TSC-C scores mediated the association between sexual abuse history and sexual intercourse by the age of 14 years. After including emotional distress in the model, the link between sexual abuse history and sexual intercourse by 14 years of age

approached statistical significance (⫽.67;P⫽.08), and the test of the mediation effect was statistically signifi-cant (z⬘ ⫽2.19;P⬍.01; Table 2).

Gender did not moderate the associa-tion between sexual abuse history and sexual intercourse at the age of 14 years. However, there was a signifi-cant interaction of gender and sexual abuse history on TSC-C scores (t389⫽

⫺3.26; P ⫽ .001). Among sexually abused youth, girls had higher TSC-C

scores than boys. The overall mediation model was not moderated by gender.

At the age of 16 years, youth with a history of sexual abuse were 2.54 times (95% CI: 1.35– 4.76;P⬍.01) more likely to have had sexual intercourse than comparison youth. There was no sup-port for either mediation by emotional distress or gender moderation.

Any Maltreatment (Excluding Sexual Abuse) and

Sexual Intercourse

To examine the relation between any maltreatment except sexual abuse and sexual intercourse by 14 or 16 years, the sample subjects were limited to youth with no history of sexual abuse, (age 14:n⫽473; age 16:n⫽348). At 14 years of age, youth with a history of maltreatment other than sexual abuse were 2.15 times (95% CI: 1.28 –3.60; P⬍.01) more likely to have sexual in-tercourse than comparison youth. Mal-treatment history was a significant predictor of TSC-C scores ( ⫽2.00; P⬍.01); youth with a history of mal-treatment had higher TSC-C scores than comparison youth (40.72 vs 38.83;

TABLE 1 Sample Characteristics

Characteristic Age 14 y (n⫽637) Age 16 y (n⫽493) Any Maltreatment

(N⫽504)

No Maltreatment (N⫽133)

Any Maltreatment (N⫽401)

No Maltreatment (N⫽92) Youth gender (female), % 50 50 54 51 Ethnicity/race, %

Black 51 67 49 67

White 29 25 28 26

Mixed race 13 5 14 2

Hispanic 6 2 7 3

Other 1 1 2 2

Sexual abuse, % 32 — 36 —

Physical abuse, % 56 — 60 —

Psychological abuse, % 74 — 77 —

Neglect, % 73 — 75 —

Sexual intercourse (yes), % 22 16 52 45 Mean TSC-C score (SD) 41.47 (7.75) 38.30 (4.21) 41.59 (8.07) 38.87 (6.89)

— not applicable.

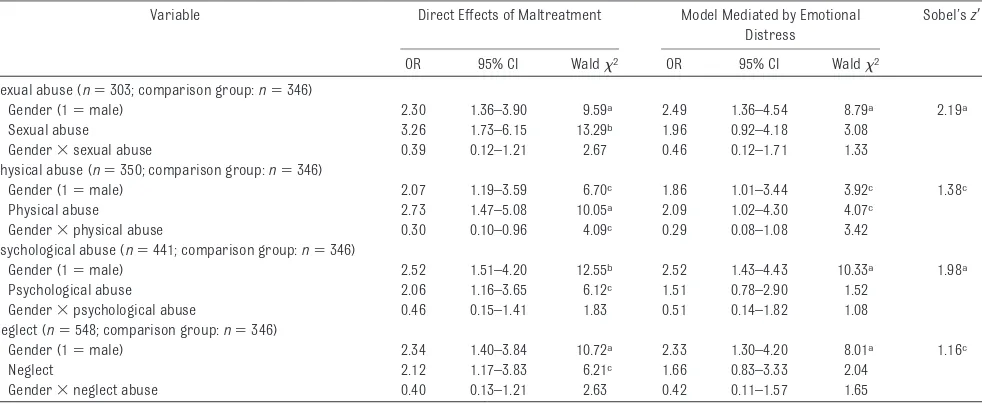

TABLE 2 Logistic Regression Models Predicting Sexual Intercourse by the Age of 14 Years According to Maltreatment Subtype With and Without Emotional Distress

Variable Direct Effects of Maltreatment Model Mediated by Emotional Distress

Sobel’sz⬘

OR 95% CI Wald2 OR 95% CI Wald2

Sexual abuse (n⫽303; comparison group:n⫽346)

Gender (1⫽male) 2.30 1.36–3.90 9.59a 2.49 1.36–4.54 8.79a 2.19a

Sexual abuse 3.26 1.73–6.15 13.29b 1.96 0.92–4.18 3.08

Gender⫻sexual abuse 0.39 0.12–1.21 2.67 0.46 0.12–1.71 1.33 Physical abuse (n⫽350; comparison group:n⫽346)

Gender (1⫽male) 2.07 1.19–3.59 6.70c 1.86 1.01–3.44 3.92c 1.38c

Physical abuse 2.73 1.47–5.08 10.05a 2.09 1.02–4.30 4.07c

Gender⫻physical abuse 0.30 0.10–0.96 4.09c 0.29 0.08–1.08 3.42

Psychological abuse (n⫽441; comparison group:n⫽346)

Gender (1⫽male) 2.52 1.51–4.20 12.55b 2.52 1.43–4.43 10.33a 1.98a

Psychological abuse 2.06 1.16–3.65 6.12c 1.51 0.78–2.90 1.52

Gender⫻psychological abuse 0.46 0.15–1.41 1.83 0.51 0.14–1.82 1.08 Neglect (n⫽548; comparison group:n⫽346)

Gender (1⫽male) 2.34 1.40–3.84 10.72a 2.33 1.30–4.20 8.01a 1.16c

Neglect 2.12 1.17–3.83 6.21c 1.66 0.83–3.33 2.04

Gender⫻neglect abuse 0.40 0.13–1.21 2.63 0.42 0.11–1.57 1.65

All of the models included covariates of age, race, and site. aP⬍.01.

t632⫽ ⫺2.99; P⬍ .01). TSC-C scores

mediated the association between maltreatment history and sexual inter-course by the age of 14 years. After including emotional distress in the model, maltreatment history was not a significant predictor of sexual inter-course by the age of 14 years (⫽.44; P⬎.15), and the test of the mediation effect was statistically significant (z⬘ ⫽1.80;P⬍.05; Table 3). There was no gender moderation.

At the age of 16 years, youth with a history of maltreatment (excluding sexual abuse) were 2.03 times (95% CI: 1.25–3.29;P⬍.01) more likely to have had sexual intercourse than compari-son youth. There was no support for mediation by emotional distress or gender moderation.

Subtypes of Maltreatment and Sexual Intercourse

Analyses were conducted to determine whether subtypes of maltreatment (physical abuse, psychological abuse,

or neglect) were associated with sex-ual intercourse by 14 years of age, and whether that association was medi-ated by emotional distress (Table 2). The associations between subtypes of maltreatment and sexual intercourse by the age of 16 years were examined, but mediation models were not tested, because emotional distress was not associated with sexual intercourse by the age of 16 years.

Physical Abuse

Youth with a physical abuse history were 2.73 times (95% CI: 1.47–5.08;P⬍ .01) more likely to report sexual inter-course by 14 years of age than com-parison youth. Physical abuse history predicted TSC-C scores (⫽4.90;P⬍ .001), and emotional distress partially mediated the association between physical abuse history and inter-course by 14 years of age. When TSC-C scores were included in the model, the indirect effects were statistically sig-nificant (zscore⫽1.38;P⬍.05), and

physical abuse predicted sexual inter-course (⫽.74;P⫽.04; Table 2).

This association between physical abuse and intercourse by the age of 14 years was moderated by gender. The association was significant for girls (odds ratio [OR]: 5.18 [95% CI: 1.81– 14.78]) but not for boys (OR: 1.80 [95% CI: 0.82–3.98];P⬎.10). Neither the as-sociation between physical abuse his-tory and emotional distress nor the overall mediation was moderated by gender.

At the age of 16 years, youth with a physical abuse history were 2.40 times (95% CI: 1.28 – 4.50; P ⬍ .01) more likely to report sexual intercourse than comparison youth. The association did not differ according to gender.

Psychological Abuse

At the age of 14, youth with a psycho-logical abuse history were 2.06 times (95% CI: 1.16 –3.65;P⫽.01) more likely to have had sexual intercourse than comparison youth. Psychological abuse predicted TSC-C scores ( ⫽ 2.70; P ⬍ .001). The association be-tween psychological abuse history and sexual intercourse by 14 years of age was fully mediated by emotional dis-tress. When TSC-C scores were intro-duced into the model, the relationship between psychological abuse and in-tercourse was not significant (⫽.41; P⫽ .22), and the indirect effect was statistically significant (z⬘ ⫽1.98;P⬍ .01; Table 2). There was no evidence of gender moderation.

At 16 years of age, youth with psycho-logical abuse history were 1.80 times (95% CI: 1.06 –3.05;P⫽.03) more likely to report sexual intercourse than com-parison youth. The association did not differ according to gender.

Neglect

By 14 years of age, youth with a neglect history were 2.12 times (95% CI: 1.17– 3.83;P⫽.01) more likely to have had

TABLE 3 Logistic Regression Models Predicting Sexual Intercourse by the Ages of 14 and 16 Years According to Any Maltreatment Except Sexual Abuse With and Without Emotional Distress

Variable Direct Effects of Maltreatment

Model Mediated by Emotional Distress OR 95% CI Wald2 OR 95% CI Wald2

Sexual intercourse by age 14 y (n⫽637) Step 1

Gender (1⫽male) 2.30 1.48–3.57 13.69a 2.36 1.43–3.91 11.23b

Age 2.04 1.29–3.22 9.43b 2.23 1.26–3.92 7.68b

Race (1⫽nonwhite) 2.93 1.55–5.54 10.94b 4.08 1.91–8.68 13.24a

Site (1⫽CPS) 0.51 0.31–0.84 6.88b 0.57 0.33–1.01 3.68

Emotional distress — — — 1.04 1.01–1.08 3.18c

Any maltreatment 2.15 1.28–3.60 8.41b 1.55 0.85–2.83 2.03

Step 2

Gender⫻maltreatment 0.44 0.15–1.26 2.36 0.47 0.14–1.62 1.41 Sexual intercourse by age 16 (n⫽493)

Step 1

Gender (1⫽male) 1.39 0.94–2.04 2.71 1.36 0.87–2.13 1.87 Age 1.59 0.98–2.57 3.55 1.60 0.92–2.78 2.72 Race (1⫽nonwhite) 1.37 0.86–2.17 1.76 1.47 0.87–2.47 2.11 Site (1⫽CPS) 0.49 0.31–0.77 9.32b 0.50 0.30–0.84 6.98b

Emotional distress — — — 0.99 0.96–1.02 0.42 Any maltreatment 2.03 1.25–3.29 8.33b 1.90 1.08–3.32 4.99c

Step 2

Gender⫻maltreatment 0.89 0.38–2.05 0.08 0.75 0.28–2.03 0.31

— variable not included in the model. aP⬍.001.

sexual intercourse than comparison youth. Neglect history predicted TSC-C scores (⫽1.81;P⫽.02). The associ-ation between neglect history and sex-ual intercourse at 14 years of age was fully mediated by emotional distress. When TSC-C scores were introduced into the model, the association be-tween neglect and sexual intercourse by the age of 14 years was not signifi-cant (⫽.51;P⫽.15), and the indi-rect effect was statistically significant (z⬘ ⫽1.16;P⬍.05; Table 2). There was no evidence of gender moderation.

By 16 years of age, youth with a neglect history were 2.58 times (95% CI: 1.45– 4.60;P ⫽.001) more likely to report sexual intercourse than comparison youth. The association did not differ according to gender.

DISCUSSION

This study confirms our first hypothe-sis that child maltreatment, defined as sexual abuse, physical abuse, emo-tional abuse, or neglect, before the age of 12 years predicts adolescent sexual intercourse at 14 years, when sexual intercourse is less common (21%), and at 16 years, when sexual inter-course is more common (51%). These findings replicate and extend previous findings that linked childhood sexual abuse and sexual behavior in adoles-cence,31including early intercourse,32

multiple partners,33lack of birth

con-trol,34and adolescent pregnancy.35

Although there is previous evidence that maltreatment other than sexual abuse predicts engagement in sexual activity36 and sexual risk behavior,37

our study is one of the first to use a prospective methodology to demon-strate that other forms of maltreat-ment increase the likelihood of sexual intercourse by 14 and 16 years of age in a high-risk sample.

A recent review concluded that there are multiple theorized pathways asso-ciated with adolescent sexual activity,

often differentiated by adolescent age.38

For example, on the basis of problem behavior theory,39 early sexual

inter-course frequently occurs, in combina-tion with other risk behaviors, when adolescents feel disenfranchised from social norms and institutions. Another possibility is that adolescents may en-gage in early sexual intercourse to al-leviate feelings of isolation or to en-hance their perceived social position with peers.40 This is a possible

path-way in maltreated youth who may feel disconnected from institutions or families that did not protect them and may be trying to alleviate mental health symptoms or to gain support. Not only is maltreatment victimization commonly associated with emotional distress as a child’s safety and family connections are threatened,8,41but

trau-matic events in childhood have been associated with sexual risk taking.42

The hypothesized pathway among child maltreatment, emotional distress, and initiation of sexual intercourse was supported at the age of 14 but not 16 years. The mediating effects of emo-tional distress at the age of 14 years are consistent with findings from ado-lescent development that sexual inter-course by 14 years of age is not a com-mon event and is often associated with behavior or school problems.38In other

words, at 12 years of age, maltreated youth reported symptoms of emotional distress that were associated with in-creased risk of sexual intercourse by 14 years of age. There are several possible explanations for the lack of effects at 16 years of age. It is possible that sexual intercourse by the age of 14 is more influenced by emotional health than during the later adoles-cent years, when intercourse is more normative. The time lapse between the measurement of emotional dis-tress (12 years of age) and the record-ing of sexual intercourse at the age of

16 years may have attenuated this relationship.

Gender Differences

Our finding that boys were more likely than girls to report sexual intercourse by the age of 14 years is consistent with reports from national data sets that boys initiate sexual intercourse earlier than girls.43,44 However, by 16

years, when sexual intercourse was more common, there were no gender differences. Although adolescent atti-tudes toward sexual intercourse differ according to gender,45,46we found only

minimal support for our third hypoth-esis that the association between mal-treatment and intercourse differed ac-cording to gender. The relation between physical abuse before the age of 12 years and sexual intercourse at the age of 14 years was stronger for girls than for boys. There were no other gender differences in the rela-tionship between child maltreatment and intercourse at either 14 or 16 years of age. In other words, child mal-treatment generally increased the like-lihood of intercourse regardless of gender.

Methodologic Strengths and Weaknesses

moderated by gender. Many studies of adolescent sexuality have been limited to 1 gender,47,48 with no attention to

gender moderation.38 Finally, a

high-risk sample was used, allowing for ad-equate power to examine the effects of maltreatment on sexual intercourse.

There are also limitations to consider. First, because the sample included children at high risk and across-site– attrition differences, similar effects may not hold in the general population. However, the association between mal-treatment and emotional distress has been demonstrated across multiple samples, suggesting that the relation-ships are not limited to children at high risk. Second, the mediated rela-tionship should be interpreted in light of possible confounding and time-related issues, with the recognition that emotional distress may not be the only possible mediator. That is, attach-ment difficulties, disorganization, and variations in social support may also mediate the relationship, and other as-pects of maltreatment (eg, severity, age, and duration) may predict both emotional distress and intercourse.

Emotional distress was not measured at the age of 14 years, and it is unclear when sexual initiation occurred. Third, self-report was used for several inde-pendent and deinde-pendent variables, raising concerns of measurement bias. The inclusion of CPS records re-duces this possibility. Fourth, the inclu-sion of both self-report and CPS records, although recommended,8,15

may increase the number of mal-treated youth. Finally, although chil-dren with higher scores regarding emotional distress were more likely to have been maltreated and to have had intercourse by the age of 14 years, the actual scores were not elevated on the basis of published norms. Thus, the children would meet independent cri-teria for emotional distress.

Clinical Implications

This article has several clinical impli-cations. First, findings lend support to the theory that primary prevention of maltreatment, among other benefits, might lead to less emotional distress and delay sexual intercourse among adolescents. The benefits of delaying intercourse extend beyond avoiding

the risk of pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections to include be-havioral and mental health concerns.49

Second, by understanding the mediat-ing role of emotional distress, clini-cians can focus their attention on ame-liorating the negative health effects of child maltreatment. Trauma-focused behavioral treatments have improved the psychological and behavioral health of maltreated children.50,51

Fi-nally, this study highlights that evalua-tions of young, sexually active adoles-cents should not be limited to risks of pregnancy and infection but should in-clude a comprehensive psychosocial assessment that addresses the possi-bility of maltreatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was funded by grants from the US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children and Families, Office on Child Abuse and Neglect, and funds from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to the Univer-sity of North Carolina Injury Prevention Research Center.

REFERENCES

1. Manning WD, Longmore MA, Giordano PC. The relationship context of contraceptive use at first intercourse.Fam Plann Perspect.2000;32(3):104 –110

2. Santelli JS, Lowry R, Brener ND, Robin L. The association of sexual behaviors with socioeconomic status, family structure, and race/ethnicity among US adolescents.Am J Public Health.2000; 90(10):1582–1588

3. Manlove J, Terry E, Gitelson L, Papillo AR, Russell S. Explaining demographic trends in teenage fertility, 1980 –1995.Fam Plann Perspect.2000;32(4):166 –175

4. Abma JC, Martinez GM, Mosher WD, Dawson BS. Teenagers in the United Status: sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing, 2002.Vital Health Stat.2004;23(24):1– 48

5. Guttmacher Institute. Facts on American teens’ sexual and reproductive health. September 2006. Available at: www.guttmacher.org/pubs/fb㛭ATSRH.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2008

6. MacKay AP, Duran C. Adolescent health in the United States. February 2008. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/misc/adolescent2007.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2008

7. Putnam FW. Ten-year research update review: child sexual abuse.J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psy-chiatry.2003;42(3):269 –278

8. Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Child maltreatment.Annu Rev Clin Psychol.2005;1:409 – 438

9. Tarren-Sweeney M. Predictors of problematic sexual behavior among children with complex maltreatment histories.Child Maltreat.2008;13(2):182–198

11. Holmes GR, Offen L, Waller G. See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil: why do relatively few male victims of childhood sexual abuse receive help for abuse-related issues in adulthood?Clin Psychol Rev.1997;17(1):69 – 88

12. Runyan DK, Curtis PA, Hunter WM, et al. LONGSCAN: a consortium for longitudinal studies of child maltreatment and the life course of children.Aggress Violent Behav.1998;3(3):235–245 13. Black MM, Ponirakis A. Computer-assisted interviews with children about maltreatment.J

Inter-pers Violence.2000;15(7):682– 695

14. Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. How the experience of early physical abuse leads children to become chronically aggressive. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, eds.Developmental Perspectives on Trauma: Theory, Research, and Intervention. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1997:263–288 15. Everson MD, Smith JB, Hussey JM, et al. Concordance between adolescent reports of childhood

abuse and Child Protective Service determinations in an at-risk sample of young adolescents.

Child Maltreat.2008;13(1):14 –26

16. English DJ; LONGSCAN Investigators. Modified Maltreatment Classification System (MMCS). 1997. Available at: www.iprc.unc.edu/longscan/pages/mmcs/LONGSCAN%20MMCS%20Coding.pdf. Ac-cessed December 15, 2008

17. Drake B, Jonson-Reid M, Way I, Chung S. Substantiation and recidivism.Child Maltreat.2003;8(4): 248 –260

18. Hussey JM, Marshall JM, English DJ, et al. Defining maltreatment according to substantiation: distinction without a difference?Child Abuse Negl.2005;29(5):479 – 492

19. Knight ED, Smith JS, Martin L, Lewis T; LONGSCAN Investigators. Measures for assessment of functioning and outcomes in longitudinal research on child abuse: volume 3— early adolescence (aged 12–14). 2008. Available at: www.iprc.unc.edu/longscan/pages/measures/Ages12to14/ index.html. Accessed December 15, 2008

20. Stanton B, Black M, Feigelman S, et al. Development of a culturally, theoretically and developmen-tally based survey instrument for assessing risk behaviors among African-American early ado-lescents living in urban low-income neighborhoods.AIDS Educ Prev.1995;7(2):160 –177 21. Briere J.Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children, Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological

Assessment Resources, Inc; 1996

22. Evans JJ, Briere J, Boggiano AK, Barrett M. Reliability and validity of the Trauma Symptom Check-list for Children in a normal sample. Presented at: the San Diego Conference on Responding to Child Maltreatment; January 28, 1994; San Diego, CA

23. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations.J Pers Soc Psychol.1986;51(6): 1173–1182

24. Sobel ME. Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In: Leinhart S, ed.Sociological Methodology 1982. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1982:290 –312

25. MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis.Annu Rev Psychol.2007;58:593– 614 26. MacKinnon DP.Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates; 2008

27. MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies.Eval Rev.1993;17(2): 144 –158

28. MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects.Psychol Methods.2002;7(1):83–104

29. Aiken LS, West SG.Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1991

30. SPSS for Windows[computer program]. Release 15.0.0. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc; 2006

31. Ohene S, Halcon L, Ireland M, Carr P, McNeely C. Sexual abuse history, risk behavior, and sexually transmitted diseases: the impact of age at abuse.Sex Transm Dis.2005;32(6):358 –363 32. Boyer D, Fine D. Sexual abuse as a factor in adolescent pregnancy and child maltreatment.Fam

Plann Perspect.1992;24(1):4 –19

33. Luster T, Small SA. Sexual abuse history and number of sex partners among female adolescents.

Fam Plann Perspect.1997;29(5):204 –211

34. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Childhood sexual abuse, adolescent sexual behaviors and sexual revictimization.Child Abuse Negl.1997;21(8):189 – 803

35. Roberts R, O’Connor T, Dunn J, Golding J; ALSPAC Study Team. The effects of child sexual abuse in later family life; mental health, parenting and adjustment of offspring.Child Abuse Neglect.

2004;28(5):525–545

37. Luster T, Small SA. Factors associated with sexual risk-taking behaviors among adolescents.

J Marriage Fam.1994;56(3):622– 632

38. Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Helfand M. Ten years of longitudinal research on U.S. adolescent sexual behavior: developmental correlates of sexual intercourse, and the importance of age, gender and ethnic background.Dev Rev.2008;28(2):153–224

39. Jessor R, Jessor S.Problem Behavior and Psychosocial Development: A Longitudinal Study of Youth. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1997

40. Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Bauer D, Ford CA, Halpern CT. Which comes first in adolescence: sex and drugs or depression?Am J Prev Med.2005;29(3):163–170

41. Meyerson LA, Long PJ, Miranda R Jr, Marx BP. The influence of childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse, family environment, and gender on the psychological adjustment of adolescents.Child Abuse Negl.2002;26(4):387– 405

42. Smith DK, Leve LD, Chamberlain P. Adolescent girls’ offending and health-risking sexual behavior: the predictive role of trauma.Child Maltreat.2006;11(4):346 –353

43. Santelli JS, Kaiser J, Hirsch L, Radosh A, Simkin L, Middlestadt S. Initiation of sexual intercourse among middle school adolescents: the influence of psychosocial factors.J Adolesc Health.2004; 34(3):200 –208

44. Grunbaum JA, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance: United States, 2003 [published corrections appear inMMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(24):536; andMMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(24):608].MMWR Surveill Summ.2004;53(2):1–96

45. Kalmuss D, Davidson A, Cohall A, Laraque D, Cassell C. Preventing sexual risk behaviors and pregnancy among teenagers: linking research and programs.Perspect Sex Reprod Health.2003; 35(2):87–93

46. Miller KE, Sabo DF, Farrell MP, Barnes GM, Melnick MJ. Athletic participation and sexual behavior in adolescents: the different world of boys and girls.J Health Soc Behav.1998;39(2):108 –123 47. Capaldi DM, Crosby L, Stoolmiller M. Predicting the timing of first intercourse for at-risk

adoles-cent males.Child Dev.1996;67(2):344 –359

48. Halpern CT, Udry JR, Campbell B, Suchindran C. Effects of body fat on weight concerns, dating, and sexual activity: a longitudinal analysis of black and white adolescent girls.Dev Psychol.1999;35(3): 721–736

49. Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Ford CA, Halpern CT, Brodish PH, Iritani B. Adolescent depression and suicide risk: association with sex and drug behavior.Am J Prev Med.2004;27(3):224 –231 50. Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Cohen JA, Steer RA. A follow-up study of a multisite, randomized,

controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms.J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.2006;45(12):1474 –1484

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-3836 originally published online August 10, 2009;

2009;124;941

Pediatrics

English

Zolotor, Alan J. Litrownik, Richard Thompson, Howard Dubowitz and Diana E.

Maureen M. Black, Sarah E. Oberlander, Terri Lewis, Elizabeth D. Knight, Adam J.

Investigation

Sexual Intercourse Among Adolescents Maltreated Before Age 12: A Prospective

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/124/3/941

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/124/3/941#BIBL

This article cites 39 articles, 0 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

ub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/child_abuse_neglect_s Child Abuse and Neglect

icine_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/adolescent_health:med Adolescent Health/Medicine

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-3836 originally published online August 10, 2009;

2009;124;941

Pediatrics

English

Zolotor, Alan J. Litrownik, Richard Thompson, Howard Dubowitz and Diana E.

Maureen M. Black, Sarah E. Oberlander, Terri Lewis, Elizabeth D. Knight, Adam J.

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/124/3/941

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.