Infant Regulation and Child Mental

Health Concerns: A Longitudinal Study

Fallon Cook, PhD,aRebecca Giallo, PhD,a,bHarriet Hiscock, PhD,a,b,cFiona Mensah, PhD,a,b,cKatherine Sanchez, SpPath(Hons),a,c,d Sheena Reilly, PhDa,b,e

abstract

OBJECTIVES:To examine profiles of infant regulatory behaviors and associated familycharacteristics in a community sample of 12-month-old infants and mental health difficulties at 5 and 11 years of age.

METHODS:Items relating to demographic characteristics, maternal distress, and infant regulation

were completed by 1759 mothers when their infants were 8 to 12 months old. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire was completed by mothers at child ages 5 (n= 1002) and 11 (n= 871) years.

RESULTS:Analyses revealed 5 profiles ranging from the most settled infants (36.8%) to those

with mainly sleep problems (25.4%), isolated mild-to-moderate tantrums (21.3%), complex regulatory difficulties (13.2%), and complex and severe regulatory difficulties (3.4%). Compared with those in the settled profile, children in the moderately unsettled profile were more likely to score in the clinical range for total difficulties at 11 years of age (odds ratio [OR] 2.85; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.28 to 6.36; P,.01), and children in the severely unsettled profile were more likely to score in the clinical range at 5 (OR 9.35; 95% CI: 2.49 to 35.11;P,.01) and 11 years of age (OR 10.37; 95% CI: 3.74 to 28.70; P,.01).

CONCLUSIONS:Infants with multiple moderate-to-severe regulatory problems experience

substantially heightened odds of clinically significant mental health concerns during

childhood, and these symptoms appear to worsen over time. Clinicians must inquire about the extent, complexity, and severity of infant regulatory problems to identify those in the most urgent need of intervention and support.

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT:Disturbed infant sleep and persistent crying have been associated with poor child outcomes. However, patterns of comorbidity across a wide range of regulatory behaviors and their combined impact on child mental health have not been examined.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS:Infants with multiple moderate-to-severe regulatory problems (3.4%) have

.10 times greater odds of experiencing significant mental health concerns during childhood compared with infants who are settled.

To cite:Cook F, Giallo R, Hiscock H, et al. Infant Regulation and Child Mental Health Concerns: A Longitudinal Study. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20180977

aMurdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia;bDepartments of Paediatrics anddAudiology and

Speech Pathology, School of Health Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia;cThe Royal

Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia; andeMenzies Health Institute Queensland, Griffith University, Gold Coast,

Australia

Dr Cook conceptualized the design of the study, drafted the manuscript, analyzed and interpreted the results, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs Giallo and Mensah conceptualized the design of the study, assisted with the data analysis and interpretation of the results, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Hiscock and Ms Sanchez conceptualized the design of the study, assisted with the interpretation of the results, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Reilly conceptualized the design of the study, supervised data collection, assisted with the interpretation of the results, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved thefinal manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0977 Accepted for publication Nov 28, 2018

Address correspondence to Fallon Cook, PhD, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Royal Children’s Hospital, 50 Flemington Rd, Parkville, VIC 3052, Australia. E-mail: fallon.cook@mcri.edu.au

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Infant behavioral dysregulation is characterized by persistent crying, irritability, and problems with feeding and sleeping.1,2These problems are common (15%–30% of infants) and result in increased help-seeking behavior and cost to the health care system.3,4Infant sleep problems are associated with poor sleep across early childhood and increased hyperactivity and emotional

difficulties at school age.5Infants with crying or sleeping problems have been consistently found to experience more internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in childhood.6Dysregulated behavior across childhood (age 4–9 years) strongly relates to early crying, sleeping, and feeding problems.1

Infant regulatory problems are likely to coexist (14.6%)7,8and involve several forms of dysregulation (eg, tantrums, mood swings, and problems sleeping, crying, and feeding). Comorbid infant regulation problems (specifically sleeping, crying, and feeding problems) have been linked to behavioral and mental health concerns during childhood, prompting the suggestion that early intervention may subvert the development of chronic dysregulated behavior throughout childhood.1,6,9 Exactly which infants should be targeted for intervention is somewhat unclear. Few researchers have examined patterns of comorbidity and severity across a broad range of infant regulatory behaviors, yet this approach may provide a more precise indication of the severity and specific combinations of regulatory problems that place some infants at greater risk for childhood mental health

difficulties.

In a large, prospective, community-based study of 1-year-old infants, we aimed to qualify the profiles of infant regulatory behaviors that were present and examine the familial and child characteristics associated with these profiles. In addition, we aimed

to examine mental health difficulties for children from each profile at 5 and 11 years of age.

METHODS

Sampling and Participants

Maternal and child health nurses across 6 local government areas of Melbourne, Australia, consecutively approached all mothers who were attending the 8-month, free well-child appointment between September 2003 and April 2004 and invited them to take part in the Early Language in Victoria Study.10The mothers of 1910 infants (82% of those approached) consented to take part. Data in the current study were drawn from questionnaires that were administered to mothers at child ages 8 to 10 months (wave 1:n= 1759), 12 months (wave 2:n= 1759), 5 years (wave 6:n= 1002), and 11 years (wave 10:n= 871). Infants with serious disabilities or

developmental delays (eg, Down syndrome or cerebral palsy) were excluded. Ethical approval was obtained from the Royal Children’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (27078 and 33195) and the La Trobe University Human Ethics Committee (03–32). All participants provided written, informed consent.

Measures

Data on child age, sex, birth weight, weeks’gestation, whether the child was admitted to the special care nursery (SCN) or NICU, and birth order were gathered from the participating mothers. Participating mothers also reported their own ages; whether they were partnered, born in Australia, and of non– English-speaking background (NESB); and whether they completed secondary school. At child age 12 months, participating mothers also completed the Kessler 6 Psychological Distress Scale (K6), which is a measure of psychological distress with strong psychometric properties.11In keeping

with previous studies, scores$8 indicated significant psychological distress.12The Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) index of relative socioeconomic disadvantage was assigned on the basis of 106 unique home postal codes, which gave a broad indication of the relative disadvantage within the geographic area of each participant (higher scores indicated less disadvantage).13

Infant Regulation at 12 Months of Age

Several measures relating to infant regulation that have been used in previous research14were completed by participating mothers.

Participating mothers indicated the presence and severity of their children’s sleep problems, excessive crying, temper tantrums, and mood swings by scoring each as either none (0), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3).15,16Global infant temperament was measured by using the following item:“Compared with other children, I think my child is: 1 = much easier than average, 2 = easier than average, 3 = average, 4 = more difficult than average, 5 = much more difficult than average.”15,16Participating mothers were asked whether their infants coughed and/or choked or gagged (yes or no) on pureed or smooth foods (eg, yogurt), mashed foods or solids (eg, potatoes), or lumpy foods (eg, peas). These items were scored with 1 point for each problem that was indicated, and this score was collapsed to form 1 variable that we used to indicate the number of feeding problems (0 for no feeding problem, 1 for 1 feeding problem, 2 for 2 feeding problems, and 3 for 3 feeding problems).

Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Outcomes

(0–40), and scores were categorized within normal (,14), borderline (14–16), or clinical (17–40) ranges. The SDQ was shown to be a reliable and valid measure for identifying children who met theDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Editioncriteria for requiring psychological treatment.18A score in the clinical range indicates a child would likely receive a diagnosis of a mental disorder.

Analyses

Latent class analysis was conducted to identify profiles of regulation at 12 months of age (Mplus version 8; Mplus Development Team, Los Angeles, CA). All 6 items in the Early Language in Victoria Study 12-month questionnaire (wave 2) pertaining to infant regulation (infant sleep problems, excessive crying, feeding problems, mood swings, temper tantrums, and global temperament) were used as indicators in the model. We aimed to identify the smallest number of profiles by starting with a parsimonious 1-class model and

fitting successive models with increasing numbers of profiles. The likelihood-ratio statistic (L2), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and Akaike information criterion (AIC) were examined across each model, with lower L2, BIC, and AIC values indicating a better modelfit. Entropy values were also examined (higher probability values indicated greater certainty in allocating participants to the profiles that were identified), and the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio (VL) indicated the significance of

differences in modelfit between each model compared with the model with 1 less profile. Each infant was classified according to his or her most likely profile membership for subsequent analyses.

Linear and logistic regression models were used to compare the

sociodemographic characteristics of infants in each identified profile with

those of the infants in the most settled profile (the profile with few or no regulatory problems). Linear regression was conducted by comparing each of the identified profiles with the most settled (reference) profile on the SDQ total difficulties score at 5 and 11 years of age. Multinomial logistic regression was conducted to compare the proportion of children who met borderline and clinical categories on the SDQ total difficulties score between each profile and the settled profile, and estimates reflecting relative odds were calculated. Estimated associations between regulatory profiles and behavior scores and/or clinical categories were controlled for potential confounders (identified a priori through an examination of previous research), including maternal characteristics (age, marital status, country of birth, NESB, school completion, and socioeconomic disadvantage), child characteristics (age, sex, birth weight, weeks’gestation, NICU or SCN admittance, and birth order), and maternal mental health (K6 score$8).

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

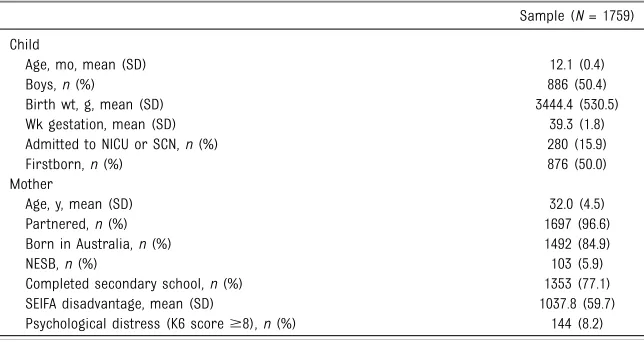

As is indicated in Table 1, our study sample comprised 1759

12-month-old infants who were of average birth weight overall (mean 3444.38 g; SD 530.49 g), with 50% being boys and 50% beingfirstborn infants.

Participating mothers were on average∼32 years old (SD 4.46),

∼97% were partnered, and 6% were NESB. Overall, the mothers in the sample lived in areas of slightly less socioeconomic disadvantage (mean 1037.80; SD 59.72) than the state average (mean 1000; SD = 100).

Profiles of Infant Regulation

Latent class models for 1 to 6 classes were estimated (Table 2). The 5-class model had the indexes with the best

fit (lower L2, BIC, and AIC values), and the VL indicated a significant difference between the 4- and 5-class models, which suggests the latter was a more appropriatefit for the data. The 5-class model had an acceptable entropy value (0.74), which indicates high certainty in allocating

participants to their most likely profile.

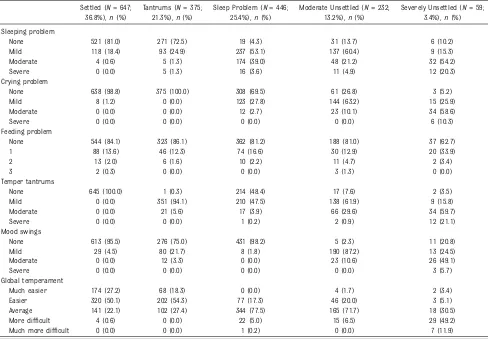

Profiles of infant regulatory behavior for each of the 5 profiles are demonstrated in Table 3. Names given to each profile are necessarily brief and indicate the predominant regulatory feature that was reported. The largest group of infants (36.8%) indicated few problems and as such was termed the settled profile. Infants in another group reported mostly

TABLE 1Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample

Sample (N= 1759)

Child

Age, mo, mean (SD) 12.1 (0.4)

Boys,n(%) 886 (50.4)

Birth wt, g, mean (SD) 3444.4 (530.5)

Wk gestation, mean (SD) 39.3 (1.8)

Admitted to NICU or SCN,n(%) 280 (15.9)

Firstborn,n(%) 876 (50.0)

Mother

Age, y, mean (SD) 32.0 (4.5)

Partnered,n(%) 1697 (96.6)

Born in Australia,n(%) 1492 (84.9)

NESB,n(%) 103 (5.9)

Completed secondary school,n(%) 1353 (77.1)

SEIFA disadvantage, mean (SD) 1037.8 (59.7)

mild, isolated temper tantrums (referred to as the tantrums profile; 21.3%), and a group characterized by mild-to-moderate sleep problems was termed as the sleep problem profile (25.4%). Infants in a moderately unsettled profile (13.2%) predominantly reported mild-to-moderate sleep problems, mild crying problems, mild-to-moderate

tantrums, and mild-to-moderate mood swings. Infants in the smallest profile (3.4%) were identified as being severely unsettled because of

greater rates of moderate-to-severe sleep problems, moderate crying problems, moderate-to-severe temper tantrums, more difficult temperament, and feeding problems. Of note, infants with severe tantrums tended to fall into the severely unsettled profile rather than the tantrums profile, and similarly, those with moderate-to-severe sleep problems tended to fall into the severely unsettled profile rather than the sleep problems profile. Those with more severe sleep or tantrum

problems tended to have many other regulatory problems, and, if mild, tantrums and sleep problems only tended to occur in isolation.

Family and Child Characteristics Associated With Infant Regulation Profiles

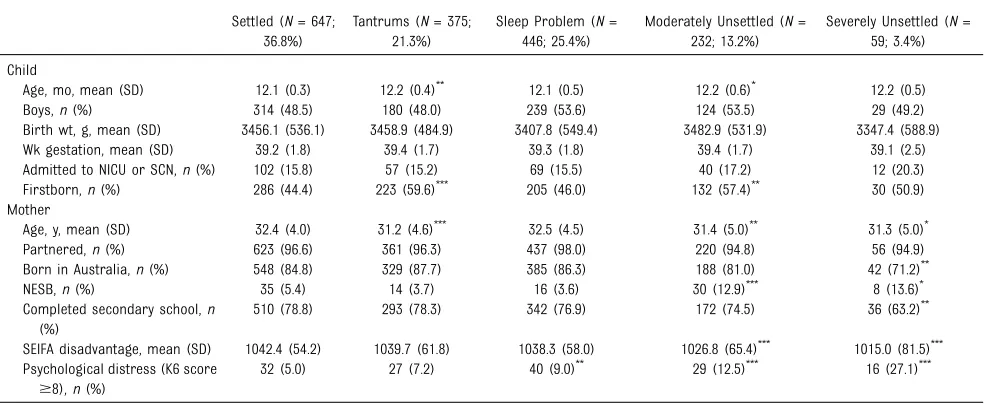

As is indicated in Table 4, mothers with infants in the severely unsettled profile compared with those who had infants in the settled profile were slightly younger (mean age 31.27 years [SD 4.98] versus TABLE 2Model Fit Information for the Latent Class Analysis

No. Profiles

L2 AIC BIC Entropy VL

2 28196.25 16 470.49 16 683.82 0.74 0.00

3 28109.86 16 337.73 16 660.60 0.70 0.00

4 28062.85 16 283.71 16 716.04 0.71 0.03

5a 28028.31 16 254.61 16 796.39 0.74 0.03

6 28015.22 16 268.45 16 919.68 0.71 0.58

aRepresents the selected model.

TABLE 3Infant Regulation Item Ratings for Each of the 5 Regulatory Profiles

Settled (N= 647; 36.8%),n(%)

Tantrums (N= 375; 21.3%),n(%)

Sleep Problem (N= 446; 25.4%),n(%)

Moderate Unsettled (N= 232; 13.2%),n(%)

Severely Unsettled (N= 59; 3.4%),n(%)

Sleeping problem

None 521 (81.0) 271 (72.5) 19 (4.3) 31 (13.7) 6 (10.2)

Mild 118 (18.4) 93 (24.9) 237 (53.1) 137 (60.4) 9 (15.3)

Moderate 4 (0.6) 5 (1.3) 174 (39.0) 48 (21.2) 32 (54.2)

Severe 0 (0.0) 5 (1.3) 16 (3.6) 11 (4.9) 12 (20.3)

Crying problem

None 638 (98.8) 375 (100.0) 308 (69.5) 61 (26.8) 3 (5.2)

Mild 8 (1.2) 0 (0.0) 123 (27.8) 144 (63.2) 15 (25.9)

Moderate 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 12 (2.7) 23 (10.1) 34 (58.6)

Severe 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 6 (10.3)

Feeding problem

None 544 (84.1) 323 (86.1) 362 (81.2) 188 (81.0) 37 (62.7)

1 88 (13.6) 46 (12.3) 74 (16.6) 30 (12.9) 20 (33.9)

2 13 (2.0) 6 (1.6) 10 (2.2) 11 (4.7) 2 (3.4)

3 2 (0.3) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 3 (1.3) 0 (0.0)

Temper tantrums

None 645 (100.0) 1 (0.3) 214 (48.4) 17 (7.6) 2 (3.5)

Mild 0 (0.0) 351 (94.1) 210 (47.5) 138 (61.9) 9 (15.8)

Moderate 0 (0.0) 21 (5.6) 17 (3.9) 66 (29.6) 34 (59.7)

Severe 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 1 (0.2) 2 (0.9) 12 (21.1)

Mood swings

None 613 (95.5) 276 (75.0) 431 (98.2) 5 (2.3) 11 (20.8)

Mild 29 (4.5) 80 (21.7) 8 (1.8) 190 (87.2) 13 (24.5)

Moderate 0 (0.0) 12 (3.3) 0 (0.0) 23 (10.6) 26 (49.1)

Severe 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 3 (5.7)

Global temperament

Much easier 174 (27.2) 68 (18.3) 0 (0.0) 4 (1.7) 2 (3.4)

Easier 320 (50.1) 202 (54.3) 77 (17.3) 46 (20.0) 3 (5.1)

Average 141 (22.1) 102 (27.4) 344 (77.5) 165 (71.7) 18 (30.5)

More difficult 4 (0.6) 0 (0.0) 22 (5.0) 15 (6.5) 29 (49.2)

32.39 years [SD 4.02]), less likely to be born in Australia (71.2% vs 84.8%), more likely to be NESB (13.6% vs 5.4%), less likely to have completed secondary school (63.2% vs 78.8%), more likely to live in an area of comparative socioeconomic disadvantage (although still greater than the state average; mean 1014.95 [SD 81.47] versus 1042.42 [SD 54.20]), and more likely to have significant mental distress (27.1% vs 5.0%). Infants who were moderately

unsettled were more likely to be

firstborn (57.4%) than the infants who were settled (44.4%). Mothers of infants in the sleep problems profile were more likely to be experiencing mental distress than mothers with infants in the settled profile (9.0% vs 5.0%). Mothers of infants in the tantrums profile were younger (mean maternal age 31.15 years [SD 4.55]) than those in the settled profile (mean maternal age 32.39 years [SD 4.02]), and infants in the tantrums

profile were more likely to be

firstborn (59.6%) than those in the settled profile (44.4%).

Associations Between Infant Regulation Profiles and Children’s Mental Health

Adjusted regression analyses

(Table 5) revealed that the 4 profiles of regulatory problems in infancy were associated with greater total behavioral difficulties at 5 years of age than the settled profile (tantrums: TABLE 4Associations Between Family and Child Characteristics and the 5 Regulatory Profiles

Settled (N= 647; 36.8%)

Tantrums (N= 375; 21.3%)

Sleep Problem (N= 446; 25.4%)

Moderately Unsettled (N= 232; 13.2%)

Severely Unsettled (N= 59; 3.4%)

Child

Age, mo, mean (SD) 12.1 (0.3) 12.2 (0.4)** 12.1 (0.5) 12.2 (0.6)* 12.2 (0.5)

Boys,n(%) 314 (48.5) 180 (48.0) 239 (53.6) 124 (53.5) 29 (49.2)

Birth wt, g, mean (SD) 3456.1 (536.1) 3458.9 (484.9) 3407.8 (549.4) 3482.9 (531.9) 3347.4 (588.9) Wk gestation, mean (SD) 39.2 (1.8) 39.4 (1.7) 39.3 (1.8) 39.4 (1.7) 39.1 (2.5) Admitted to NICU or SCN,n(%) 102 (15.8) 57 (15.2) 69 (15.5) 40 (17.2) 12 (20.3) Firstborn,n(%) 286 (44.4) 223 (59.6)*** 205 (46.0) 132 (57.4)** 30 (50.9) Mother

Age, y, mean (SD) 32.4 (4.0) 31.2 (4.6)*** 32.5 (4.5) 31.4 (5.0)** 31.3 (5.0)* Partnered,n(%) 623 (96.6) 361 (96.3) 437 (98.0) 220 (94.8) 56 (94.9) Born in Australia,n(%) 548 (84.8) 329 (87.7) 385 (86.3) 188 (81.0) 42 (71.2)**

NESB,n(%) 35 (5.4) 14 (3.7) 16 (3.6) 30 (12.9)*** 8 (13.6)*

Completed secondary school,n (%)

510 (78.8) 293 (78.3) 342 (76.9) 172 (74.5) 36 (63.2)**

SEIFA disadvantage, mean (SD) 1042.4 (54.2) 1039.7 (61.8) 1038.3 (58.0) 1026.8 (65.4)*** 1015.0 (81.5)*** Psychological distress (K6 score

$8),n(%)

32 (5.0) 27 (7.2) 40 (9.0)** 29 (12.5)*** 16 (27.1)***

*P,.05. **P,.01. ***P,.001.

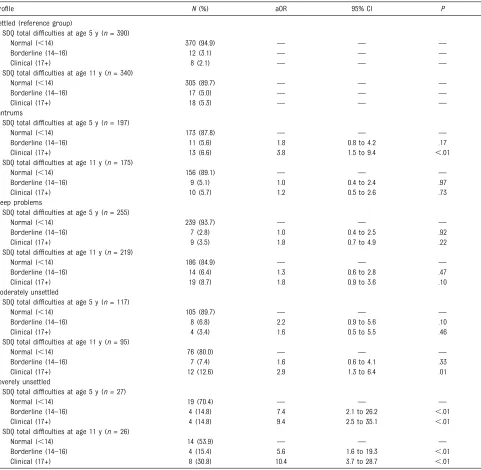

TABLE 5Total Difficulties for Each Profile at 5 and 11 Years of Age With the Settled Profile as the Reference Group

Mean (SD) AMD 95% CI P

Settled (reference group)

Total difficulties at age 5 y (n= 390) 6.1 (4.1) — — —

Total difficulties at age 11 y (n= 340) 6.4 (5.1) — — —

Tantrums

Total difficulties at age 5 y (n= 197) 7.3 (4.9) 1.1 0.4 to 1.9 .01 Total difficulties at age 11 y (n= 175) 7.2 (5.5) 0.7 20.4 to 1.8 .19 Sleep problems

Total difficulties at age 5 y (n= 255) 7.1 (4.4) 0.9 0.2 to 1.6 .02 Total difficulties at age 11 y (n= 219) 7.7 (6.0) 1.3 0.3 to 2.3 .02 Moderately unsettled

Total difficulties at age 5 y (n= 117) 8.4 (4.1) 2.2 1.2 to 3.1 ,.01 Total difficulties at age 11 y (n= 95) 8.1 (6.6) 2.0 0.6 to 3.4 .01 Severely unsettled

Total difficulties at age 5 y (n= 27) 10.4 (5.1) 3.7 1.9 to 5.4 ,.01 Total difficulties at age 11 y (n= 26) 12.1 (6.8) 5.4 3.1 to 7.7 ,.01

adjusted mean difference [AMD] 1.14 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.35 to 1.93;P= .01]; sleep problems: AMD 0.87 [95% CI: 0.15 to 1.59;P= .02]; moderately unsettled: AMD 2.17 [95% CI: 1.20 to 3.14;P,.01]; severely unsettled: AMD 3.65 [95% CI: 1.87 to 5.42;P,.01]). At 11 years of age (Table 5), infants in the sleep problems profile, moderately unsettled profile, and severely unsettled profile were associated with greater total behavioral difficulties than those in the settled profile (sleep problems: AMD 1.27 [95% CI: 0.25 to 2.29;P= .02]; moderately unsettled: AMD 1.96 [95% CI: 0.57 to 3.35;P= .01]; severely unsettled: AMD 5.42 [95% CI: 3.10 to 7.74;P,.01]), but no differences were evident for infants in the tantrums profile.

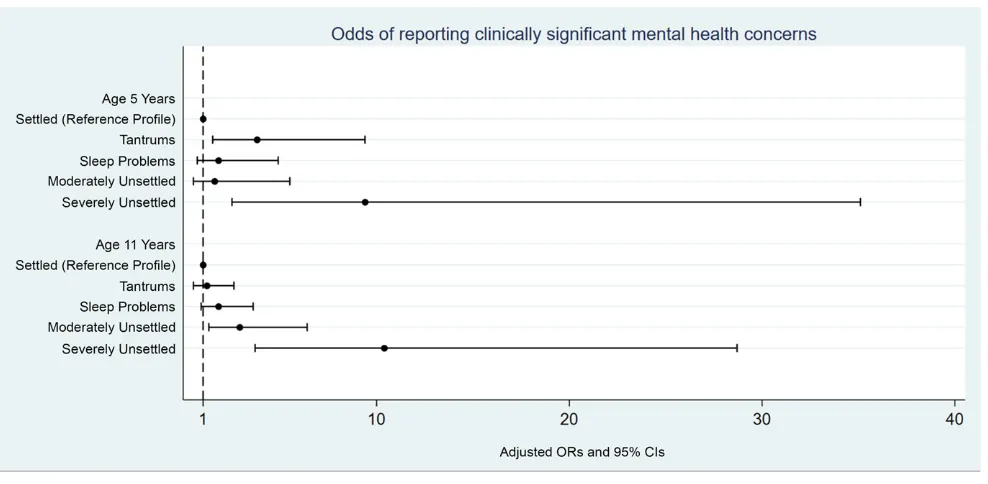

In adjusted analyses (Table 6, Fig 1), children in the tantrums profile had higher odds of scoring in the clinical range (odds ratio [OR] 3.79; CI: 1.53 to 9.41;P,.01) for total difficulties at 5 years of age. Children in the severely unsettled profile had higher odds of scoring in the borderline range (OR 7.44; CI: 2.11 to 26.22;

P,.01) and clinical range (OR 9.35; CI: 2.49 to 35.11;P,.01) for total difficulties at 5 years of age. At 11 years of age, children in the moderately unsettled profile had higher odds of scoring in the clinical range for total difficulties (OR 2.85; CI: 1.28 to 6.36;P,.01). Children in the severely unsettled profile had higher odds of scoring in the borderline range (OR 5.56; CI: 1.61 to 19.25;P,.01) and clinical range (OR 10.37; CI: 3.74 to 28.70;P,.01) for total difficulties at 11 years of age.

DISCUSSION

In a community cohort of 12-month-old infants and their mothers, an analysis of 6 brief items pertaining to multiple facets of infant regulation revealed 5 distinct profiles. In comparison with infants in the settled

profile, those in each profile reported greater total behavioral difficulties at 5 and 11 years of age (except for the tantrums profile at 11 years of age). Broadly, as the complexity and severity of reported infant regulatory problems increased, so did the tendency to report mental health difficulties during childhood. At 5 years of age, infants from the severely unsettled profile in

comparison with those in the settled profile staggeringly had 7.44 and 9.35 times higher odds of scoring in the borderline and clinical ranges for mental health concerns, respectively, even after accounting for potential confounding variables. Previous research suggests that those scoring in the clinical range would be likely to receive a formal diagnosis of a mental disorder.17,18The odds of scoring in the clinical range further increased for this profile to 10.37 at 11 years of age, which indicated that on average, symptoms for the severe profile worsened over time. Notably, infants in the moderately unsettled profile had 2.85 times greater odds of scoring in the clinical range for total

difficulties at 11 years of age than those in the settled profile. Although infants in the tantrums profile had 3.79 times greater odds of scoring in the clinical range at 5 years of age, this was no longer apparent at 11 years of age, which indicates a shift toward recovery during the early school years. For infants in this profile, early tantrums and the associated poor outcomes in early childhood seem to be outgrown by middle childhood.

To our knowledge, the 5 profiles of infant regulation that we have identified and described here have not been identified in the scientific literature. Our results confirm that sleep and tantrum problems do seem to occur in isolation for some infants (25% and 21%, respectively), but these tend to be only mild in intensity and have few repercussions for mental health during early-to-middle childhood. However, for∼16% of

infants, regulation difficulties tend to be complex and involve multiple, overlapping symptoms of moderate-to-severe intensity. Examining a single component of regulation in isolation (such as sleep) may not provide enough detail to identify those at risk for later mental health difficulties. Although infants in each profile had increased total difficulties in comparison with those in the settled profile, only infants with multiple moderate-to-severe problems had greater odds of scoring in the clinical range for mental health problems at 11 years of age. That is,

∼30% of the infants in the severely unsettled profile had mental health concerns in the borderline or clinical ranges at 5 years of age, and this increased to.46% by 11 years of age.

Infants from the moderately unsettled profile and tantrums profile were more likely to befirstborns, and mothers of infants in the severely unsettled profile, moderately unsettled profile, and tantrums profile were slightly younger than those who had infants in the settled profile. Mothers offirstborn infants and younger mothers may report more problematic infant behavior because of unfamiliarity with normal infant behavior. Previous research indicates young mothers may engage in fewer positive parenting practices and report more difficult child behavior.19Mothers of infants in the severely unsettled profile compared with those who had infants in the settled profile were less likely to be born in Australia, more likely to be NESB, less likely to have completed secondary school, and more likely to live in areas of comparative

profile. These mothers may have less social and familial support and face language barriers when seeking help for their infants who are unsettled.20

Approximately 5% of mothers of infants in the settled profile reported clinically significant psychological distress; however, this number was significantly greater in the sleep problems profile (∼9%), moderately

unsettled profile (12.5%), and severe profile (∼27%). Previous research has repeatedly revealed an association between infant sleep problems and maternal depression and distress.21–25Ourfindings indicate that multiple moderate-to-severe infant regulatory problems are associated with greatly increased rates of maternal distress, with approximately one-third of mothers

with infants who are severely unsettled reporting distress in the clinical range. Interventions that are targeted at the mother-infant dyad rather than the infant regulatory problem in isolation may be the most appropriate for these families.

The infant regulation items that we administered in the current study are not exhaustive and may not TABLE 6Borderline and Clinical Cutoff Points for the Total Difficulties Score at 5 and 11 Years of Age for Each Profile

Profile N(%) aOR 95% CI P

Settled (reference group)

SDQ total difficulties at age 5 y (n= 390)

Normal (,14) 370 (94.9) — — —

Borderline (14–16) 12 (3.1) — — —

Clinical (17+) 8 (2.1) — — —

SDQ total difficulties at age 11 y (n= 340)

Normal (,14) 305 (89.7) — — —

Borderline (14–16) 17 (5.0) — — —

Clinical (17+) 18 (5.3) — — —

Tantrums

SDQ total difficulties at age 5 y (n= 197)

Normal (,14) 173 (87.8) — — —

Borderline (14–16) 11 (5.6) 1.8 0.8 to 4.2 .17

Clinical (17+) 13 (6.6) 3.8 1.5 to 9.4 ,.01

SDQ total difficulties at age 11 y (n= 175)

Normal (,14) 156 (89.1) — — —

Borderline (14–16) 9 (5.1) 1.0 0.4 to 2.4 .97

Clinical (17+) 10 (5.7) 1.2 0.5 to 2.6 .73

Sleep problems

SDQ total difficulties at age 5 y (n= 255)

Normal (,14) 239 (93.7) — — —

Borderline (14–16) 7 (2.8) 1.0 0.4 to 2.5 .92

Clinical (17+) 9 (3.5) 1.8 0.7 to 4.9 .22

SDQ total difficulties at age 11 y (n= 219)

Normal (,14) 186 (84.9) — — —

Borderline (14–16) 14 (6.4) 1.3 0.6 to 2.8 .47

Clinical (17+) 19 (8.7) 1.8 0.9 to 3.6 .10

Moderately unsettled

SDQ total difficulties at age 5 y (n= 117)

Normal (,14) 105 (89.7) — — —

Borderline (14–16) 8 (6.8) 2.2 0.9 to 5.6 .10

Clinical (17+) 4 (3.4) 1.6 0.5 to 5.5 .46

SDQ total difficulties at age 11 y (n= 95)

Normal (,14) 76 (80.0) — — —

Borderline (14–16) 7 (7.4) 1.6 0.6 to 4.1 .33

Clinical (17+) 12 (12.6) 2.9 1.3 to 6.4 .01

Severely unsettled

SDQ total difficulties at age 5 y (n= 27)

Normal (,14) 19 (70.4) — — —

Borderline (14–16) 4 (14.8) 7.4 2.1 to 26.2 ,.01

Clinical (17+) 4 (14.8) 9.4 2.5 to 35.1 ,.01

SDQ total difficulties at age 11 y (n= 26)

Normal (,14) 14 (53.9) — — —

Borderline (14–16) 4 (15.4) 5.6 1.6 to 19.3 ,.01

Clinical (17+) 8 (30.8) 10.4 3.7 to 28.7 ,.01

accurately encompass all aspects of infant regulation. Children did not complete diagnostic interviews for mental disorders. Replication of this work in other longitudinal cohorts is required. This study has several strengths, including a prospective design and large community sample. We used a data-driven approach that allowed for a more comprehensive examination of the overlap and severity of regulation problems than has been conducted previously.

Infants with multiple moderate-to-severe regulatory problems are at greatly increased risk of later mental health concerns and as such may benefit from targeted intervention and referral to support services. Infants with 1 or 2 mild regulatory problems should be closely

monitored. Providers inquiring about the presence and severity of multiple regulatory problems may identify infants with a high burden of comorbidity that extends into

childhood. The presence of multiple moderate-to-severe infant regulatory problems may indicate the beginning of a trajectory toward poor child mental health. Subsequent research should investigate whether early intervention can improve outcomes for these children and potentially curtail the rising trend of emergency department attendance for child mental health problems.26,27

CONCLUSIONS

Infants with multiple moderate-to-severe regulatory problems experience.10 times the odds of clinically significant mental health concerns during childhood, and these symptoms appear to worsen over time. Six brief items pertaining to the presence and severity of regulatory problems may be used to identify infants who require more in-depth assessment. When parents report concern about a regulatory problem in their 12-month-old infant,

clinicians must inquire about the extent, complexity, and severity of other regulatory problems to identify those in most urgent need of intervention and support.

ABBREVIATIONS

AIC: Akaike information criterion AMD: adjusted mean difference BIC: Bayesian information

criterion

CI: confidence interval K6: Kessler 6 Psychological

Distress Scale

L2: likelihood-ratio statistic NESB: non–English-speaking

background OR: odds ratio

SCN: special care nursery SDQ: Strengths and Difficulties

Questionnaire

SEIFA: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas

VL: Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio

FIGURE 1

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE:The authors have indicated they have nofinancial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING:Supported by project grants 237106, 9436958, and 1041947 from the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) and grants from the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and the La Trobe University Faculty of Health Sciences. Drs Reilly, Hiscock, Giallo, and Mensah were supported by fellowships from the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia). Ms Sanchez was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Research at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute is supported by the Government of Victoria’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program. The funding organizations are independent of all researchers and had no role in the design and conducting of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the decision to submit the article for publication; or the preparation, review, or approval of the article.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST:The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

COMPANION PAPER:A companion to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2018-3922.

REFERENCES

1. Winsper C, Wolke D. Infant and toddler crying, sleeping and feeding problems and trajectories of dysregulated behavior across childhood.J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42(5):831–843

2. Hyde R, O’Callaghan MJ, Bor W, Williams GM, Najman JM. Long-term outcomes of infant behavioral dysregulation. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/ 130/5/e1243

3. Morris S, James-Roberts IS, Sleep J, Gillham P. Economic evaluation of strategies for managing crying and sleeping problems.Arch Dis Child. 2001; 84(1):15–19

4. St James-Roberts I. Infant crying and sleeping: helping parents to prevent and manage problems.Prim Care. 2008; 35(3):547–567, viii

5. Williams KE, Nicholson JM, Walker S, Berthelsen D. Early childhood profiles of sleep problems and self-regulation predict later school adjustment.Br J Educ Psychol. 2016;86(2):331–350

6. Hemmi MH, Wolke D, Schneider S. Associations between problems with crying, sleeping and/or feeding in infancy and long-term behavioural outcomes in childhood: a meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(7):622–629

7. Hiscock H, Cook F, Bayer J, et al. Preventing early infant sleep and crying problems and postnatal depression: a randomized trial.Pediatrics. 2014; 133(2). Available at: www.pediatrics. org/cgi/content/full/133/2/e346

8. Wolke D, Meyer R, Orth B, Riegel K. Co-morbidity of crying and feeding problems with sleeping problems in infancy: concurrent and predictive

associations.Infant Child Dev. 1995;4(4): 191–207

9. Barnevik Olsson M, Carlsson LH, Westerlund J, Gillberg C, Fernell E. Autism before diagnosis: crying, feeding and sleeping problems in the

first two years of life.Acta Paediatr. 2013;102(6):635–639

10. Reilly S, Cook F, Bavin EL, et al. Cohort profile: the Early Language in Victoria Study (ELVS).Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(1): 11–20

11. Furukawa TA, Kessler RC, Slade T, Andrews G. The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for

psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being.Psychol Med. 2003;33(2): 357–362

12. Martin J, Hiscock H, Hardy P, Davey B, Wake M. Adverse associations of infant and child sleep problems and parent health: an Australian population study. Pediatrics. 2007;119(5):947–955

13. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas. Canberra, Commonwealth of Australia; 2001. Available at: http://abs.gov.au/ AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/2033.0. 55.0012001?OpenDocument. Accessed June 23, 2006

14. Sanson A, Nicholson J, Ungerer J, et al. Introducing the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Institute of Family Studies; 2002

15. Prior M, Sanson A, Oberklaid F. The Australian Temperament Project. In: Kohnstamm G, Bates J, Kleyjord Rothbart M, eds.Temperament in Childhood. Oxford, England: John Wiley and Sons; 1989:639

16. Fullard W, McDevitt SC, Carey WB. Assessing temperament in one- to three-year-old children.J Pediatr Psychol. 1984;9(2):205–217

17. Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note.J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997; 38(5):581–586

18. Goodman R, Scott S. Comparing the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and the Child Behavior Checklist: is small beautiful?J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1999;27(1):17–24

19. Fox RA, Platz DL, Bentley KS. Maternal factors related to parenting practices, developmental expectations, and perceptions of child behavior problems. J Genet Psychol. 1995;156(4):431–441

20. May KM. Middle-Eastern immigrant parents’social networks and help-seeking for child health care.J Adv Nurs. 1992;17(8):905–912

21. Smart J, Hiscock H. Early infant crying and sleeping problems: a pilot study of impact on parental well-being and parent-endorsed strategies for management.J Paediatr Child Health. 2007;43(4):284–290

22. Giallo R, Dunning M, Gent A. Attitudinal barriers to help-seeking and

preferences for mental health support among Australian fathers.J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2017;35(3):236–247

23. Armitage R, Flynn H, Hoffmann R, Vazquez D, Lopez J, Marcus S. Early developmental changes in sleep in infants: the impact of maternal depression.Sleep. 2009;32(5):693–696

Maternal mental health and the quality of infant sleep.Soc Sci Med. 2013;79: 101–108

25. O’Connor TG, Caprariello P, Blackmore ER, Gregory AM, Glover V, Fleming P; ALSPAC Study Team. Prenatal mood disturbance predicts sleep problems in

infancy and toddlerhood.Early Hum Dev. 2007;83(7):451–458

26. Hiscock H, Neely RJ, Lei S, Freed G. Paediatric mental and physical health presentations to emergency

departments, Victoria, 2008–15.Med J Aust. 2018;208(8):343–348

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2018-0977 originally published online February 8, 2019;

2019;143;

Pediatrics

Sheena Reilly

Fallon Cook, Rebecca Giallo, Harriet Hiscock, Fiona Mensah, Katherine Sanchez and

Infant Regulation and Child Mental Health Concerns: A Longitudinal Study

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/143/3/e20180977 including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/143/3/e20180977#BIBL This article cites 24 articles, 5 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/sleep_medicine_sub

Sleep Medicine

y_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/psychiatry_psycholog

Psychiatry/Psychology

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2018-0977 originally published online February 8, 2019;

2019;143;

Pediatrics

Sheena Reilly

Fallon Cook, Rebecca Giallo, Harriet Hiscock, Fiona Mensah, Katherine Sanchez and

Infant Regulation and Child Mental Health Concerns: A Longitudinal Study

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/143/3/e20180977

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.