Abstract: The study of archaeological plant remains from Castelo Velho, is used to investigate the wood and food resources available in the area during the period from the Copper to the Bronze Age. Results obtained show clear discrepancies in taxa frequencies through the sequence. The paucity of the carpological remains is particularly noticed. The importance of Arbutus unedo (wood and fruits) is pinpointed in layer 2 (Bronze Age).

Key-words: Plant remains; Copper Age; Bronze Age; wood and food resources; Mediterranean vegetation.

Resumo: O estudo de vestígios vegetais recolhidos na estação de Castelo Velho é utilizado na inves-tigação dos recursos lenhosos e alimentares nesta área, durante o Calcolítico e a Idade do Bronze. Os resultados obtidos mostram que a abundância dos taxa varia ao longo da sequência. A pobreza em vestígios carpológicos é particularmente notada assim como a importância de Arbutos unedo (carvões e frutos) na camada 2 (Idade do Bronze).

Palavras-chave: Vestígios vegetais; Calcolítico; Idade do Bronze; recursos lenhosos e alimentares; vegetação mediterrânica.

I. INTRODUCTION

The study of the plant remains from Castelo Velho (Freixo de Numão) offers the opportunity to investigate the vegetation and the environment surrounding the settlement during its occupation and furthermore to evaluate the availability of wood and food resources and how they might have been used by the local populations.

The site is situated on a hill top (681m) dominating the surrounding region. At present, this area is assigned to the Submediterranean – Iberian/Mediterranean phytoclimatic

SIGNIFICANCE

byIsabel Figueiral*

* ESA 5059, Institut de Botanique, 163, Rue A. Broussonet, 34090 Montplellier, France. E-mail: figueir@crit.univ-montpr.fr

zone characterized by Juniperus oxycedrus (Juniper), Olea europaea var. sylvestris (wild Olive tree), Quercus rotundifolia (Holm Oak) and Quercus suber (Cork Oak) (Albuquerque, 1954). Part of the archaeological site has been destroyed by recent Eucalyptus plantations and nearby, cultivated fields include olive trees, vines and fruit trees.

Sampling of charcoal and fruits/seeds was carried out mostly by means of dry sieving of sediments (2mm mesh) collected from the three archaeological levels identified (Jorge, 1993): – Layer 4 (Copper Age) – related to the 1st phase of occupation, prior to the building

of the defensive wall.

– Layer 3 (Final Copper Age) – phase during which the defensive walls and several domestic structures are built. Areas possibly linked with activities such as weaving, crop processing and storage are also recognized.

– Layer 2 (Early-Middle Bronze Age) – last phase of occupation when structures built during the 2nd phase (layer 3) are used again.

II. RESULTS OBTAINED

II.1. The charcoal fragments

A total of 1868 fragments of charcoal has been analysed. Quantitative results are summarised in Tables 1 and 2. Taxa identified include (in alphabetic order):

Arbutus unedo (Strawberry-tree), Cistaceae, Clematis vitalba (Vide-branca), Daphne gnidium (Trovisco), Erica arborea (Heath), cf.Ericaceae , Fraxinus angustifolia (Ash), Juniperus type oxycedrus /phoenicea (Juniper), Leguminosae (Legumes), Monocotyledo-neous, Prunus sp., Quercus (deciduous) (Deciduous Oak), Quercus (evergreen) (Evergreen Oak), Quercus suber (Cork Oak), Quercus sp., Rhamnus/Phillyrea (cf. Mediterranean Buckthorn), Rosaceae Pomoidea (Rosacea), Indetermined 1.

The taxonomic list obtained is mainly composed of mediterranean elements as should be expected in this particular area of northern Portugal. Results show:

Layer 4 (Table 1): dominance of Quercus (evergreen), followed by Leguminosae and Rosaceae Pomoidea (most probably hawthorn). The presence of Fraxinus, Quercus (deciduous) and Arbutus is also noted.

Layer 3 (Tables 1 and 2): dominance of Quercus (evergreen), both in the scattered and concentrated charcoal (relative frequency slightly lower than in layer 4). The sporadic presence of Juniperus and the importance of Cistaceae in the two fireplaces identified are also noted.

Layer 2 (Tables 1 and 2): Clear dominance of Arbutus both in the scattered and concentrated charcoal, followed by Leguminosae.

The main changes observed in this short sequence are summarized in figure 1. Ecological significance of plant record

Three different species of a same genus may be concerned by the nomination Quercus (evergreen) – Quercus rotundifolia, Quercus coccifera and Quercus suber. The distinction of these species, based on the wood anatomy characters alone, is very difficult.

In some fragments, issued from mature trees, it was possible to distinguish clearly Quercus suber. Some other fragments seem closer to Quercus rotundifolia. These two species grow spontaneously in Portugal either forming monospecific populations known as

“montados” or in mixed communities. Both species require direct light and relatively warm climate. Quercus suber, however, needs higher humidity than Quercus rotundifolia.

The fragments of deciduous Quercus identified may belong to the species Quercus faginea, a mediterranean oak which sheds its leaves very late in the year.

Other mediterranean elements include Juniperus (most probably Juniperus oxycedrus), Rosaceae Pomoidea (anatomical characters appear to be similar to those of Crataegus monogyna ) and Arbutus. The importance of Arbutus in the site is quite clear. It grows in the midst of the evergreen forest taking advantage of clearances and fire to spread, prefering humid or sudhumid climates (as characterized by Emberger); it may also grow in drier climates when local conditions provide greater edaphic or climatic humidity (Costa Tenorio, Mora Juaristi y Sainz Ollero, eds, 1998).

Most of the remaining taxa fall within the range of heliophilous plants characterizing woodland clearance: Leguminosae, Erica, Cistaceae , Daphne.

All taxa refered to above are thermophilous elements. The only mesophilous taxa identified are Fraxinus and Salix.

Similarities and discrepancies in the different levels

The first similarity concerns the length of the taxonomic lists themselves with only short lists obtained for all layers; the five main taxa – Quercus (evergreen), Quercus (deciduous), Quercus suber, Arbutus unedo, Leguminosae and Rosaceae Pomoidea – are present in all three layers.

Other similarities concern only two of the levels: predominance of Quercus (evergreen), importance of Rosaceae and presence of Quercus (deciduous) in layers 4 and 3, while Cistaceae and Daphne are common to layers 3 and 2.

It is therefore possible that the human communities using this settlement might have had relatively similar (qualitative) range of wood resources for their activities. However, clear quantitative discrepancies are evident, the most noticeable being the increased frequency of Arbutus unedo, which becomes dominant in layer 2, at the expense of Quercus (evergreen) and Rosaceae Pomoidea (Figure 1).

General comments

The overall picture that emerges from our results is that of a spectrum of taxa composed of mostly thermophilous and heliophilous woody plants.

The most remarkable feature from the data assembled here comes from the last layer (Level 2) when Arbutus suddenly takes over and dominates the taxonomic spectrum both in the scattered and concentrated charcoal samples. If we are to believe the accuracy of relative frequencies of charcoal for palaeoenvironmental reconstructions, the image obtained in the level 2 would be similar to some present-day Iberian plant communities which are dominated by Arbutus. Some of the best examples of these communities are refered to in “Los bosques ibéricos” (Costa Tenorio, Mora Juaristi y Sainz Ollero, eds, 1998): in the northwestern area of the province of Badajoz and in the Sierra de la Peña de Francia.

In terms of ecology, the presence of Arbutus is a sign of forest degradation due to either repeated clearance of evergreen oaks or fire. The spread of Arbutus also requires the existence of a decarbonatation process.

In general terms we may consider that the two first archaeological layers correspond to a period when the climax vegetation of the area (evergreen forest with Quercus rotundifolia and Quercus suber) was still important. The composition and structure of this forest undergoes clear changes following anthropogenic disturbance as shown by the

presence of pioneer elements, such as Arbutus, Leguminosae, Erica, and Cistaceae, representing open conditions.

What is surprising is that, in level 2, there is a sharp change from dominance of Quercus (evergreen) to dominance of Arbutus without a transition phase with relatively high frequencies of Erica. We recall that this taxon was not identified in layers 4 and 3 and that from the 25 samples analysed in layer 2 only one had charcoal fragments issued from Erica arborea. Cleared soils from a former evergreen forest are usually colonised by Erica (pioneer stage), while Arbutus only spreads during a later phase.

How may we explain this situation? To start with, two main hypotheses concerning the significance of our results may be put forward:

1. Results from layer 2 reflect the reality and are therefore an indicator of a real ecological change following extensive woodland clearance

2. Results from layer 2 reflect only a selection of a favoured species during a certain period

If the first hypothesis is taken into account, how can we explain the near absence of Erica? One explanation is possible: an occupation gap might have occurred between layers 3 and 2; the last occupation phase could have taken place in a moment when Arbutus had already replaced the heathers as main species. If the second hypothesis is considered four main possibilities should be taken into account:

a) a different technical exploitation of the natural vegetation takes place during layer 2.

b) a clear woodland management policy (such as coppicing) might have been carried out, favouring the exploitation of Arbutus. However, in the long run, this would most likely be noticed while analysing the growth rings of the charcoal fragments (as normal growth is slowed down).

c) layer 2 corresponds to a short-term occupation and Arbutus is over-represented probably as a result of being collected preferentially on account of its fruits or some other unknown reason. We recall that the use of Arbutus as fuel for baking bread (ovens) and metalurgy has been refered to by Rivera y Obón (1991) and López González (1983). Also, in Greece, the use of its bark for tanning has been refered to by Fournier (1947).

d) charcoal from layer 2 is linked with ritual practices of some kind and Arbutus was especially chosen. The fact that the fruits are supposedly narcotic should be taken into account (Fournier, 1947).

Only the study of additional material from this same site and from other settlements in the region will give us the key to interpret our results further. We recall however that similar results have been recorded at Cueva de los Murciélagos (Andaluzia) (Rodriguez Ariza, 1995, Gavilan et al., 1997). In this settlement the importance of Arbutus is noted since the Middle Palaeolithic (Gavilan et al . 1997). During the Middle Neolithic a peak of Arbutus is recorded (layer A – 56,7% ; layer B – 50,18%) followed by a decrease in the subsequent layers (layer C (final Neolithic) – 42%, Copper Age – 32,5%, Bronze Age – 35,5%) (Rodriguer Ariza, 1995).

Another aspect should be taken into consideration, that is the sparcity of mesophilous taxa. In fact, and although the site is situated in the vicinity of two small waterlines, only two elements clearly related to the riverside vegetation (Fraxinus and Salix) are identified.

We recall that Fraxinus is identified only in layer 4 while Salix is identified in layer 2 (concentrated charcoal).

II.2. Fruits / Seeds

Apart from charcoal fragments, the carbonised plant remains fall into 3 categories: fruits, pulses and cereals. They are rare and occured only in five of the samples from layer 2. The results are as follows:

Hordeum vulgare (barley) – 1; Lathyrus sativus (grass pea) – 1; Lathyrus cicera / sativus – 2; Lathyrus sativus / Pisum sativum – 1; Lens culinaris (lentil) – 1; Pisum sativum (field pea) – 10, Rosaceae (fragment) – 1; Arbutus unedo (arbutus berry) (fragments) – 11; Arbutos unedo (arbutus berry) (whole) – 3.

Only one grain of cereal was identified in this study – Hordeum vulgare L (six-row barley). This cultivated species is reported in Portuguese archaeological contexts from the Copper Age onwards (Hopf, 1991). Barley is sensitive to soil acidity and grows best in regions of moderate rainfall and where the ripening season is relatively long and cool (Renfrew, 1973).

Pulses are represented by field pea (Pisum sativum), grass pea (Lathyrus sativus) and lentil ( Lens culinaris). The presence of Pisum sativum in Portuguese sites has been pointed out, for the first time, by Pinto da Silva (1988), in Vila Nova de S. Pedro (Copper Age). It requires a cool growing season and absence of severe frosts. It grows best under a relatively humid climate (Renfrew, 1973).

The presence of Lathyrus cicera has been frequently recorded in archaeological contexts from Portugal. According to Pinto da Silva (1988) it would have been used mostly as fodder. Its use as humam food would concern only very poor populations and / or periods of food shortage.

Concerning Lens culinaris, rarely mentioned in Portuguese sites, its presence had already been noted in a Bronze Age level at Buraco da Pala (Serra de Passos), (Rego and Rodriguez, 1993). Lentils are susceptible to frost and grow best in a warm dry climate (Renfrew, 1973).

The most important find concerns the berries of Arbutus unedo, seldom recorded in archaeological sites. Its sporadic presence has been recorded in northern Spain, Italy (Mesolithic), southern France (Final Neolithic – Bronze Age) (Hopf 1991). In Portugal, the presence of two carbonized berries had been already pinpointed at Castro do Zambujal (in a Copper Age / Early Bronze Age context) (Hopf, 1981). The berries, which have a high content of sacarose, reach their maturity in the autumn.

III. CONCLUSIONS

Only the study of additional material (and further sites) will allow us to understand more fully the results obtained so far and to recognize the real role of this settlement in the region. In terms of the palaeoecology, taxa identified appear to suggest the existence of climatic conditions slightly different from those of today. At present, this area is characterized by a very dry climate, while the presence of deciduous oak, cork oak and strawberry-tree in the taxonomic spectrum seems to indicate the existence of a sub-humid climate (600 – 1000mm).

Concerning the carpological remains we can but be surprised with their scarcity, as crop processing and storage areas have been identified in the settlement. We may ask ourselves if the structures identified really concerned the storage of cereals, and if so whether they were consumed in situ or used mostly in trade.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

ALBUGUERQUE, J. P. M. Carta ecológica de Portugal. Dir. Geral Serv. Agric., Lisboa, 52 pp, 1 map 1/500 000.

FABIÃO, A. M. D. (1987) – Árvores e florestas, col. Euroagro, publ. Europa-América, 228 pp.

FOURNIER, P. (1947) – Le livre des plantes médicinales et vénéneuses de France, vol. I: 104-106.

GAVILLAN, B.; VERA, J. C.; CEPILLO, J. J.; DELGADO, M. R.; MARFIL, C.; MARTINEZ, M. J.; MOLINA, A.; MORENO, M.; RAFAEL, J. J.; RODRIGUEZ-ARIZA, M. O. (1997) – El poblamiento prehistorico del Macizo de Cabra y la Alta Campiña (Córdoba). Bases de partida y primeros resultados de um proyecto arqueo-lógico sistemático. in BALBIN BERHMAM, R. and BUENO RODRIGUEZ, P. (eds) II Congresso de Arqueologia Peninsular. Neolitico, Cobre y Bronce., Zamora, T. II: 165 – 176.

HOPF, M. (1981) – Pflanzlich Reste aus Zambujal. in SANGMEISTER, E. & SCHUBART, H., Zambujal, Die Grabungen 1964 bis 1973: 315 – 340.

HOPF, M. (1991) – South and Southwest Europe. in VAN ZEIST,W., WASYLIKOWA, K., BEHRE K.-E. (eds) Progress in Old World Palaeoethnobotany, Balkema, Rotterdam, PP. 241-277.

JORGE, S. O. (1993) – O povoado de Castelo Velho (Freixo de Numão, Vila Nova de Foz Côa) no contexto da Pré-história Recente do Norte de Portugal. Trabalhos de Antro-pologia e Etnologia, vol. 33 (1-2): 179 – 216.

LOPEZ GONZALEZ, G. (1982) – La guia de Incafo de los árboles y arbustos, Incafo, Madrid.

PINTO da SILVA (1988) – A paleobotânica na arqueologia portuguesa. Resultados desde 1931 a 1987. in QUEIROGA, F., SOUSA, I. and OLIVEIRA, C. (eds) Paleoecologia e Arqueologia: 5 – 36, 14 estampas.

RENFREW, J. (1973) – Palaeoethnobotany. The prehistoric food plants of the Near East and Europe. Methuen & Co Ltd, London, 248 pag, 48 pl.

RIVERA, D.; OBON C. (1991) – La guia incafo de las plantas útiles y venenosas de la Península Ibérica y Baleares (excluidas medicinales). Incafo, Madrid.

REGO, P. R.; RODRIGUEZ, M. J. A. (1993) – A palaeocarpological study of Neolithic and Bronze Age levels of the Buraco da Pala rock-shelter (Bragança, Portugal). Veget. Hist. and Archaeobot., 2: 173-186.

RODRIGUEZ-ARIZA, M. O. (1995) – Análisis antracológicos de yacimientos neolíticos de Andalucía. Actas I Congrés del Neolític a la Península Ibérica, Gavà-Bellaterra, pp. 73-83.

ROZEIRA, A. (1944) – A flora da província de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro (estudo de distribuição geográfica). Trab. Inst. Bot. Gonçalo Sampaio, 54 pp.

Table 1 – Dispersed charcoal – absolute and relative frequencies of taxa Castelo Velho

(Results based on scattered charcoal)

Layer 4 Layer 3 Layer 2

Taxa n° % n° % n° % Arbutus unedo 19 7.1 43 20.3 296 42.6 Cistaceae 2 0.9 38 5.5 cf. Clematis sp. 1 0.1 Daphne gnidium 4 1.9 5 0.7 Erica arborea 30 4.3 Fraxinus angustifolia 8 3

Juniperus type oxycedrus/phoenicea 2 0.9

Leguminosae 42 15.7 19 8.9 160 23 Monocotiledoneous 5 0.7 Prunus sp. 6 0.9 Quercus (deciduous) 2 0.9 Quercus (evergreen) 124 46.3 80 37.7 36 5.2 Quercus suber 4 1.5 15 7.1 52 7.5 Quercus sp. 1 0.4 1 0.5 3 0.4 Rhamnus/Phillyrea 4 0.6 Rosaceae Pomoidea 43 16 21 9.9 8 1.2 Indetermined 12 1.7 Indeterminable 27 10 23 10.8 39 5.6 TOTAL 268 212 695

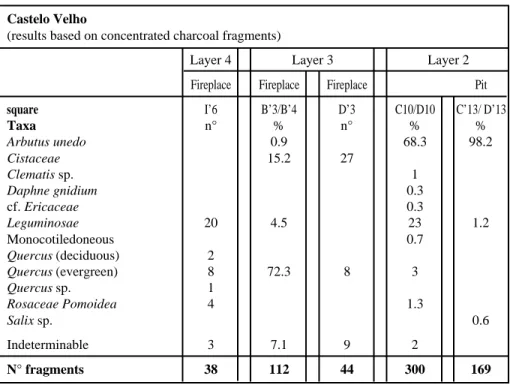

Castelo Velho

(results based on concentrated charcoal fragments)

Layer 4 Layer 3 Layer 2

Fireplace Fireplace Fireplace Pit

square I’6 B’3/B’4 D’3 C10/D10 C’13/ D’13 Taxa n° % n° % % Arbutus unedo 0.9 68.3 98.2 Cistaceae 15.2 27 Clematis sp. 1 Daphne gnidium 0.3 cf. Ericaceae 0.3 Leguminosae 20 4.5 23 1.2 Monocotiledoneous 0.7 Quercus (deciduous) 2 Quercus (evergreen) 8 72.3 8 3 Quercus sp. 1 Rosaceae Pomoidea 4 1.3 Salix sp. 0.6 Indeterminable 3 7.1 9 2 N° fragments 38 112 44 300 169