Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology

Volume 5 | Issue 1

Article 4

1914

Sex Morals and the Law in Ancient Egypt and

Babylon

James Bronson Reynolds

Follow this and additional works at:

https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc

Part of the

Criminal Law Commons

,

Criminology Commons

, and the

Criminology and Criminal

Justice Commons

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons.

Recommended Citation

SEX MORALS AND THE LAW IN ANCIENT EGYPT AND

BABYLON.

JAMEs BuoNsoN REYNoLDS.'

EGYPT.

Present knowledge of the criminal law of ancient Egypt relating to sex morals is fragmentary and incomplete in spite of the fact that considerable light has been thrown upon the subject by recent excava-tions and scholarship. We have not yet, however, sufficient data to de-termine the character or moral value of Egyptian law, or of its in-fluence on the Medeterranean world.

Egyptian law was, however, elaborately and carefully expanded during the flourishing period of the nation's history.2 Twenty thousand volumes are said to have been written on the Divine law of Hermes, the traditional law-giver of Egypt, whose position is similar to that of Manu in relation to the laws of India. And while it is impossible to trace the direct influence of Egyptian law on the laws of later nations, its indirect influence upon the founders of Grecian law is established beyond ques-tion. Both Lycurgus and Solon visited Egypt and are said to have made special study of its laws and particularly of its Criminal code.3

Our present sources of information regarding the criminal laws of Egypt are limited chiefly to descriptive narratives of ancient writers of alien nations, which are incomplete, superficial and often contradic-tory. The Egyptian monuments up to the present time have contributed but scant information on the subject. Strabo, Herodotus and

Athen-aeus (who quotes Ctesias) are our chief informants regarding Egyp-tian penal law in relation to sex morals. All we are warranted to be-lieve as to Egyptian laws relating to public morality fron these meagre and somewhat questionable authorities may be briefly summarized.

According to the "unwritten law" of the best public sentiment, as stated in the Maxims of Ani on a Boulaq papyrus, immorality was strongly condemned. The' wise man thus warns the youth: "Guard thee from the woman from abroad who is not known in her city; look not on her, know her not in the flesh; for she is a flood great and deep, whose whirling no man knows. The woman whose husband is far away, 'I am beautiful,' says she to thee every day. When she has no witnesses

10f the New York Bar. General Counsel, American Social Hygiene Association, Inc.2

Historical Jurisprudence. Guy Carlton Lee. 3

she stands and ensnares thee. 0 great crime worthy of death when one hearkens, even when it is not known abroad, (for) a man takes up every sin (after) this one."4 Yet it is said that along with these wholesome and righteous ideals, widespread and gross immorality flourish.' The warning just quoted seems to suggest that the scarlet woman was well known in the land. Prostitution was probably common and among the ranks of the courtesans were many married women whose husbands had left them, and who wandered about the country practising their profes-sion.6 An overlord might and probably did at times abuse his power by making the daughters of his inferiors subjects of his passion, yet such ac-tion is openly condemned by a nobleman in proclaiming his own right-cous record. "There was no citizen's daughter whom I misused."'7

The king also might freely exercise his power to gratify his pas-sion as was possible in Europe in the Middle Ages. A king is described as "the man who takes women from their husbands whither he wills and when his heart desires."8

Adultery.-Adultery with a married woman was a moral wrong and a crime. The standards of the time in relation to sex morality are set forth in a document entitled the Negative Confession (part of Chapter

125 of the Book of the Dead.) In Clause 19 we read: "I have not defiled the wife of a husband," that is, the wife of another man. That adultery was a legal offence against the law is evidenced by a text of the reign of Ramses V (about 1150 B. C.) containing a list of the crimes charged against a shipmaster at Elephantine. The list includes a charge of adultery with two women, each of whom is described as "mother of 11. and wife of N." The didactic papyri also warn against adultery as well as against fornication. Ptahhotep says: "If thou desirest to prolong friendship in a house which thou enterest as master, as colleague or as friend, or wheresoever thou enterest, avoid approach-ing the women; no place prospereth where that is done. ... A

thousand men have been destroyed to enjoy a short moment like a dream; one attaineth death in knowing it." This text is not later than

the Middle Kingdom.

The story of Ubaaner turns on the adultery of his. wife with a peas-ant, who is given to a'crocodile to be devoured. The woman is burned.

4

Development of Religion and Thought in Ancient Egypt. p. 357. James Henry Breasted.

'History of the Ancient Egyptians. p. 84 James Henry Breasted. Ctesias, Athenaeus, XIII, 10.

0

Osiris and the Egyptian Resurrection. E. A. Wallis Budge.

7Ancient Records of Egypt. Vol. I, p. 523. James Henry Breasted. 8

Hlerodotus tells of a King, Pheron,-who gathered his unfaithful wives into one town and destroyed them by fire.

That the husband had no obligation to the wife if he divorced her on the ground of adultery may be inferred from two marriage contracts of the 26th Dynasty. In the latter Ptolemaic marriage contracts, writ-ten in Greek, adultery and all forms of marital infidelity are forbidden

to both husband and wife. The penalty for the husband is the forfeiture of the dowry, that of the wife is not specified. The contracts of mar-riage during the Roman period also prescribe a blameless life, but less ih detail.10

The laws of Egypt in relation to public morals and particularly to adultery were harsh and cruel." They were, however, no more severe, so far as we know, than those of Europe in the Middle Ages.

A married woman convicted of adultery was punished by slitting the 'nose, for the reason that that feature was the most conspicuous and

the loss thereof would be most severely felt and be the greatest detri-ment to personal charms.'2

The maleaccomplice of a woman guilty of adultery was punished by a thousand blows of the lash.

Rape.-Rape was punished by death. In the case of foreigners this

punishment was sometimes commuted to exile. The violation of a free woman was punished by mutilation of the male offender, on the al-leged ground that the crime involved three great wrongs: Insult, de-filement and bastardy.3

Prostitution.-Prostitution apparently was tolerated. A foreign writer cites the instance of one king said to have prostituted his daugh-ter in order to discover a robber, and of another king, Cheops, ",ho pros-tituted his daughter to obtain money for the construction of the pyramid bearing his name. Such tales, however, are justly subject to suspicion and savor more of court scandals than of serious history.

. Temple prostitution is believed to have been practiced and certain

religious festivals were accompanied by immoral dances. But the re: ligious and secular authorities sought to prevent its practice as appears in a law mentioned by Rerodotus forbidding sexual intercourse within the walls of a temple.'4

From the above review of the survivals of Egyptian criminal law

9Herodotus II. 60, 64.

10Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics. Art. Adultery. F. L. Griffith. "'Ancient Egyptians. Sir John Gardner WilknsQn. Vol. I, p. 303.

12Idenm Vol. I, p. 304.

"3Thonissen, J. 3. Etudes sur l'histoire de droit criminel des peoples an-dens. Vol. I, p. 153. (See also Diodorus Book I, Chap. VI, Laws 12 and 13.)4

it appears that prostitution existed but was penalized probably, only. when practiced in sacred places; that adultery was punished by criminal and civil penalties and that rape was punished by death.

LAWS CITED. Law against Adultery.

Law against Rape.

Law against Temple Prostitution.

PRINCIPAL AUTHORITIES ON EGYPT.

Athenaeus, XIII. 190-240 A. D. (about). Diodorus, Book I, Chap. 6. First Cent. B. C. Herodotus, Vol. II. 484-425 B. C.

Breasted, James Henry.-History of the Ancient Egyptians. New York, 1908. Idem.-Development of Religion and Thought in Ancient Egypt. New

York, 1912.

Idem.-Ancient R cords of Egypt. 5 vols. Chicago, 1905, 1907.

Budge, E. A.-Wallis.-Osiris and the Egyptian Resurrection. London, 1911. Capart, Jean.-Esquisse d'une histoire de Droit p6nal 6gyptien. Revue de

l'Universite de Bruxelles. Feb., 1900. Erman, Adolf.-Life in Ancient Egypt. London, 1894.

Griffith, F. L.-Art. "Crimes and Punishments," Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics. New York, 1912.

Lee, Guy Carlton.--Historical Jurisprudence. New York, 1900. Sethe, Kurt.-Die altaegytischen Pyramidentexte. Leipzig, 1908.

Thonissen, J. J.-M6moire sur l'organisation judiciaire, les lois p~nales et la procedure criminelle de l'Egypte -ancienne. M6moires de l'Academie royale de Belgique. Brussels, 1865. Vol. 35.

Idetr.-Etudes sur l'histoire de droit ciiminel des peoples anciens. Brus-sels, 1869. 2 vols.

Wilkinson. Sir John Gardner.-Ancient Egyptians. New York, 1879.

BABYLON.

The Code of Ejammurabi, the fotainder of the Babylonian Empire, is the most ancient code of laws dealing with sexual vice of which we have definite knowledge and is supposed to have been proclaimed about 2000 B. C.

Even this Code was not the first law of the land. It is a compila-tion of existing laws and of still older Sumerian laws. How far back the foundations of the laws of Babylon reach, no one knows. Long be-fore the Code of Etammnrabi, possibly as early as 3500 B. C., a single

Sumerian tablet contained a brief reference to sex morality:

"If a wife hate her husband and say to him 'Thou art not my hus-band,' they may throw her into the river."

"If a husband say to his wife 'Thou art not my wife' he shall pay her one-half a mana of silver."

The Code is recognized as the work of a ruler of great wisdom and foresight who sought equal justice for the strong and the weak. Itis laws 'reveal a devout paternal ruler, actuated by the principles that un-derlie all just legislation.

The central purpose of the Code is explained on a tablet accom-panying iammurabi's likeness: "That the great should not oppress the weak, to counsel the widow and orphan-to judge the judgment of the land,- to decide the decisions of the land (and) to succor the in-jured."1

The Code of Elammurabi endured for more than 1500 years as the fundamental law of the Babylonian and Assyrian Empires.2 It em-braced both civil and criminal law, no distinction being made between the two. Discovered but recently, its historical relations to universal criminal jurisprudence are little known.3 Its influence on Roman and Greek law has yet to be determined. There is already, however, little doubt that the Code contributed to the Mlosaic Law, though their parallels and analogies may be due to the common Semitic origin of the two systems.4 The resemblance between the Mosaic law and the Babylonian code is particularly manifest in their statutes relating to the rape of a betrothed maiden, though the contrast in details is perhaps as notable as the resemblances.

The difference between the two systems is also striking. Ham-murabi, in dealing with seduction or rape, does not handle the case of the unbetrothed virgin, as does the Hebrew law, while his treatment of the betrothed virgin differs from that of the Eebrew law. Hammurabi inflicts the penalty of burning (incest with mother, Section 157), of drowning (adultery with neighbor's wife, Section 129, and of daughter-in-law for incest, Section 155), of banishment (incest with daughter, Section 154) and of disinheritance (incest with step-mother, Section

158.) In the Old Testament the punishments are death (incest with step-mother or daughter-in-law, Lev. 20:11 and 12), burning (bigamy, marriage of woman and her mother, Lev. 20:14), disinheritance (incest with sister, Lev. 20:17) and even childlessness (incest with wife of uncle or brother, Lev. 20:20 and 21.)'

The Code must be understood as having been devised for a people not fully emerged from the patriarchal state. Incest, so elaborately

'Johns, C. H. W. Babylonian and Assyrian Laws, Contracts and Letters. P. 393.2

Kent, Charles F. Israel's Laws and Legal Precedents. p. 5.

3Discovered in Susa the ancient Persepolis, by De Morgan, in December,

1901, and January, 1902.

4Cook, S. A. The Laws of Moses and the Code of Hammurabi.

5

handled and so severely punished, frequently occurred under that so-cial order. The careful determination of the varying duties of the wife, during the absence of the husband as a soldier revealed a people in whose life war was a chief concern. Nevertheless, there is evidence of a rel-atively settled national existence. Courts were well established and rules of legal procedure determined, though extreme reliance on the testimony of eye-witnesses indicates the immaturity of legal development.

In the interpretation of the Code, two points of procedure must be borne in mind. First, most mandates were permissive rather than peremptory. "Shall," for instance, denotes often not the imperative mode but the future tense. In some cases it is clearly permissive, as when the Code says a widow "shall" marry again. Second, the judge appears to have liberal powers as to the infliction of penalties. Hence, the apparent harshness of certain penalties may have been softened in practice through the exercise of judicial discretion. The judge, for in-stance, might grant a defendant six months' grace to find witnesses to save his life from a death sentence. When these points are considered, the Code apparently is not more drastic than those of the Middle Ages, or even of a later period, when a man was hanged for sheepstealing.

We may now consider sections of the Code relating directly and indirectly to our subject.

Lawful Marriage.7-We find in the Code that marriage retained the form of purchase, but was essentially a contract, the woman legally not becoming a wife until the contract had been executed.8

Abandonment.--Abandonment by the husband was condemned. It was regarded as violation of the marriage contract, releasing the wife from her obligation of fidelity. The wife of a man guilty of abandon-ment was not compelled to return to her husband should he come back to his own city.

Desertion.'0-- The right of the absent soldier to the fidelity of his

OThe Code may be found in full in Babylonian and Assyrian Laws, Con-tracts and Letters. Johns, C. H. W.

7Sec. 128. If a man has taken a wife and has not executed a marriage contract, that woman is not a wife.

sEncyclopaedia Britannica. Art. Babylonian Law.

wife was scrupulously protected, if he had made suitable provision for

his family. In the event of such provision, if the wife were unfaithful, her punishment was drowning, and this punishment was inflicted even though the husband had been taken captive. Probably some litigation was recognized as to the length of time during which a woman was required to assume that her hsuband was still living. The Code, however, in-dicates no period of time which created a presumption that the hus-band was dead.

If the husband had failed to provide for his wife, she was then free to seek another husband. In other words, it appears that the con-1 ract of marriage imposed upon the husband the obligation to provide for his wife in order to retain his right to her fidelity..

If the man taken captive subsequently returned, though he had made no provision for his family, his wife was obliged to go back to him. The children of the second husband, however, remained with the latter.

0

Divorce.1 1-The wife could divorce the husband only for open adultery. The legal grounds stated in the Code under which the hus-band could divorce his wife were barrenness, aeglect of domestic duties

lOSec. 133. If a man has been taken captive, and there was maintenance in his house, but his wife has left her house and entered into another man's

house; because that woman has not preserved her body, and has entered into the house of another, that woman shall be prosecuted and shall be drowned.

Sec. 134. If a man has been taken captive, but there was not maintenance in his house, and his wife has entered into the house of another, that woman has no blame.

Sec. 135. If a man has been taken captive, but there was no maintenance in his house for his wife, and she has entered into the house of another, and has borne him 'children, if in the future her (first) husband shall return and regain his city, that woman shall return to her first husband, but the children shall follow their own father.

"iSec. 137. If a man has determined to divorce a concubine who has borne

htm children, or a votary who has granted him children, he shall return to that woman her marriage portion and shall give her the usufruct of field, garden and goods, to bring up her children. After her children have grown up, out of whatever is given to her children, they shall give her one son's share, and the husband of her cohice shall marry her.

Sec. 138. If a man has divorced his wife, who has not borne him children, he shall pay over to her as' much money as was given for her bride-price, and the marriage portion which she brought from her father's house, and so shall divorce her.

Sec. 141. If a man's wife, living in her husband's house, has persisted in going out, has acted the fool, has wasted her house, has belittled her husband, he shall prosecute her. If her husband has said: "I divorce her." she shall go her way; he shall give her nothing as her price of divorce. If her husband has said, "I will not divorce her," he may take another woman to wife; the wife shall live as a slave in her husband's house.

and the broad ground of acting the fool. On this last pretext almost any incident displeasing to the husband could be adduced as cause, but a concubine or a votary might be divorced without cause, provided her marriage portion were returned and provision were made for herself and her children.

A concubine was a woman who cohabited with a man without the legal or social standing of a wife.

A votary was a semi-priestess or vestal virgin whose life had been consecrated to religion. She might marry, but must remain a virgin. She could, however, give her maid to her husband and he might have children by the latter, the children being regarded as legally the children

of the votary.

Adulter.1 2-- Adultery among the Babylonians was solely the crime of the wife. The wife, if caught in the act, was punished by strangling, to-gether with her paramour. The husband, however, might condone the offence of his wife, but in that event, lie could not call for the punishment of her male accomplice. If the wife, though accused by the husband, were

not caught in the act, she might return home, but if she had become a subject of scandal, her guilt or innocence might, upon the demand of the hsuband, be tested by requiring her to plunge into the sacred river. In that event it was assumed that if innocent, she would float; if guilty, she would drown.

The nearest approach to punishment of the husband for adulter-ous acts seems to have been that in the event of his immoralities be-coming open and scandalous, the wife might take her marriage portion and return to her parental home. The respective rights and duties of husband and wife are summarized in the doctrine that if the husband

12Sec. 129. If a man's wife be caught lying with another, they shall be strangled, and cast into the water. If the wife's husband would save his wife, the king can save his servant.

Sec. 131. If a man's wife has been accused by her husband, and has not been caught lying with andther, she shall swear her innocence and return to her house.

Sec. 132. If a man's wife has the finger pointed at her on account of another, but has not been caught lying with him, for her husband's sake she shall plunge into the sacred river.

Sec. 142. If a woman has bated her husband and has said, "You shall not possess me," her past shall be inquired into, as to .what she lacks. If she has been discreet, and has no vice, and her husband has gone out, and has greatly belittled her, that woman has no blame, she shall take her marriage portion and go off to her father's house.

belittled the wife, she might desert him. If the wife belittled the hus-band she should or might be drowned.

Incest.'3-Incest was punished by banishment, strangling or burn-ing, according to the closeness of relationship between the offenders. In the severity of the punishment we may note the care taken to protect family morals.

Rape.14-- Rape was seduction of the betrothed wife of another, pro-vided she were a virgin and living in the house of her father. The pun-ishment was death, to be inflicted only if the offenders were caught in the act. Direct evidence was required. Circumstantial evidence was not admitted or was~not concliusive. Conviction was probably rare and the severity of the penalties of the law in unusual instances was the guarantee of its efficiency.

Prositution.15-The nearest approach to reference to prostitution is in sections relating to beer houses kept by women. These seem to have been places of ill-repute and probably were frequently houses of prostitu-tion. A votary not dwelling in a convent who lived in a beer house or entered a beer house to drink was put to death. The severity of this penalty inflicted upon the votary who thus compromised her reputa-tion for scrupulous morality is in striking contrast to the temple pros-titution of a later period. But neither prospros-titution itself nor commer-cialized vice in any form was penalized in the Code of E'ammurabi. The prostitute was literally an abandoned woman, ignored by the law.

To summarize, the Code of ilammurabi pre-eminently protected family morals, ruthlessly penalized any immoral dereliction of the wife of improper intimacy within forbidden degrees of consanguinity, mildly condemned the open infidelity of the husband if the wife objected, and there halted its injunctions. Defective in -some points, ruthlessly severe in others, it was nevertheless superior in its treatment of sex morality to the laws of Greece and Rome, and probably affected substantially the

later Semitic codes.

13See Code of Hammurabi, Section 154 to Section 158.

14Sec. 130. If a man 'has ravished another's betrothed wife, who is a virgin, while still living in her father's house, and has been caught in the act, that man

shall be put to death; the woman shall go free.

1 5

SEX MORALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT AND BABYLON

In the later history of Babylon, as given by the Greek, Roman and Hebrew authorities, there are indications that the earlier laws failed to protect public morals when the simpler conditions of the pastoral and patriarchal state were superceded by the luxuries of conquest and the complexities of urban development. Warfare was succeeded by general debauchery, and the decadent Babylon of the time of Alexander had long ceased to be restrained by the laws of the stern and righteous

Ham-murabi. /

Mluch less is known as to the laws of Babylon relating to sex of-fences in later centuries. Babylon was denounced in the Apocalypse as "the mother of the harlots and of the abominations of the earth."10 Herodotus, Strabo and Baruch made the definite and serious charge that temple prostitution of all Babylonian women was ordained by law and universally practiced. It was also later asserted that at the time of Alexander the Great the gross immorality of the Babylonian people reached its climax, and women of the best families were notoriously guilty of acts of glaring immodesty.7 Yet, in spite of these declara-tions, the extreme depravity of the social status of Babylon is less well established than has been supposed. Among the ancient records the tale of Herodotus as to the universal prostitution of Babylonian women is the most circumstantial and elaborate. lie is authority for the state-ment that every Babylonian female was required by law to prostitute herself once in her life in the temple of Mlylitta, the Chaldean Venus.'8

Strabo'8 and the Book of Baruch20

bear similar testimony. But Strabo is believed to have borrowed most of his details as to Babylonian customs

.JORevelations 17:5. "--and upon her forehead a name written, Mystery, Babylon the great, the mother of the harlots and of the abominations of the earth." (American Standard Version.)

"7Quintus Curtius Rufus, The Life of Alexander the Great. (Eng. trans-lation). p. 140.

"sHerodotus I, 199: "The most disgraceful of the Babylonian customs is the following: Every native woman is obliged once in her life to sit in the temple of Venus and have intercourse with some stranger." Herodotus then proceeds to describe the method by which this surrender was made, declaring that the obligation was universal and obeyed by women of all classes.

19Strabo, Book XVI, Chap. 1:20. "There is a custom prescribed by an oracle for all Babylonian women to have intercourse with strangers." The main details given by Herodotus are then repeated.

0

from Elerodotus, and the author of the Book of Baruch quite possibly obtained his information from the same source. At most he refers only to certain indeterminate practices, not, as does Herodotus, to a gen-eral custom. Denunciatory exaggerations of conditions in Babylon by returned Hebrew captives and their descendhnts were not unnatural, and it is probable that the writer of Baruch was strongly influenced by them. The captive sees the worst side of life, and his judgments arc inevitably biased by his experience and point of view. Phat considerable immorality existed after the nation had acquired wealth and captives, easily debauched, is probable. Erotic references in the cuneiform litera-ture of Babylonia equally fail to corroborate the sweeping accusations of Herodotus against the entire nation.

Erotic language relating to certain temple rites is mystical and sym-bolic, and its significance as an actual record of conditions and laws in relation to sex morality may easily have been exaggerated. The charges in Herodotus appear, therefore, to rest in part on exaggeration, in part on a misunderstanding of religious rites and are unsupported by any in-dependent and competent evidence, either local or foreign, and until such evidence is furnished may justly be regarded as unproven.2' In

any event, it must be borne in mind that Herodotus writes of a period hundreds of years later than the age of Hammurabi. Certainly there is no hint of such customs or conditions in the austere laws of Elammurabi, and we may fairly hold that the period of Hammurabi's reign a repu-table inhabitant of a modern city 'would find the moral condition of ancient Babylon less shocking than that of mediaeval Europe.

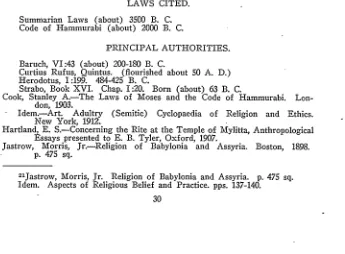

LAWS CITED.

Summarian Laws (about) 3500 B. C. Code of Hammurabi (about) 2000 B. C.

PRINCIPAL AUTHORITIES.

Baruch, VI:43 (about) 200-180 B. C.

Curtius Rufus, Quintus. (flourished about 50 A. D.) Herodotus, 1:199. 484-425 B. C.

Strabo, Book XVI. Chap. 1:20. Born (about) 63 B. C.

Cook, Stanley A.-The Laws of Moses and the Code of Hammurabi. Lon-don, 1903.

- Idem.-Art. Adultry (Semitic) Cyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics. New York, 1912.

Hartland, E. S.-Concerning the Rite at the Temple of Mylitta, Anthropological Essays presented to E. B. Tyler, Oxford, 1907.

Jastrow, Morris, Jr.-Religion of Babylonia and Assyria. Boston, 1898. p. 475 sq.

2"Jastrow, Morris, Jr. Religion of Babylonia and Assyria. p. 475 sq.

Idem. Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice. pps. 137-140.

[image:12.612.41.386.394.648.2]SEX MORALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT AND BABYLON

Idem.-Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice. New York, 1911. pps. 137-140

Johns, C. H. W Babylonian and Assyrian Laws, Contracts and Letters. New York, 1904.

Idem.-Art. Babylonian Law. Encyclopaedia Britannica. London, 1910. Kent, Charles F.-Israel's Laws and Legal Precedents. New York, 1907. Lyon, D. G.-Structure of the Hammurabi Code. Journal of the American

Oriental Society, Vol. XXV, pps. 248-278. New Haven. Conn., 1904. MacCulloch, J. A.-Art. Crimes and Punishments. Cyclopaedia of Religion

and Ethics. New York, 1912.

Rogers, Robert W.-Cuneiform Parallels to the Old Testament. New York, 1912.