Adolescent Medicine Training in Pediatric Residency Programs: Are We

Doing a Good Job?

S. Jean Emans, MD*§; Terrill Bravender, MD*§; John Knight, MD‡§; Carolyn Frazer, MD‡§; Maria Luoni, BA*; Carol Berkowitz, MDi; Elizabeth Armstrong, PhD¶§; and Elizabeth Goodman, MD*§

ABSTRACT. Objectives. To determine how pediatric residency programs are responding to the new challenges of teaching adolescent medicine (AM) to residents by assessing whether manpower is adequate for training, whether AM curricula and skills are adequately covered by training programs, what types of teaching methodol-ogies are used to train residents in AM, and the needs for new curricular materials to teach AM.

Design. A 3-part 92-item survey mailed to all US pe-diatric residency training programs.

Setting. Pediatric residency programs.

Participants. Residency program directors and direc-tors of AM training.

Main Outcome Measures. AM divisional structure,

clinical sites of training, presence of a block rotation, and faculty of pediatric training programs; training materials used and desired in AM; perceived adequacy of coverage of various AM topics; competency of residents in per-forming pelvic examinations in sexually active teens; and manpower needs.

Results. A total of 155/211 (73.5%) of programs com-pleted the program director and the AM parts of the survey. Ninety-six percent of programs (size range, 5–120 residents) had an AM block rotation and 90% required the AM block; those without a block rotation were more likely to be larger programs. Only 39% of programs felt that the number of AM faculty was adequate for teaching residents. Almost half of the programs reported lack of time, faculty, and curricula to teach content in substance abuse. Besides physicians, AM teachers included nurse practitioners (28%), psychologists (25%), and social work-ers (19%). Topics most often cited as adequately covered included sexually transmitted diseases (81.9%), confiden-tiality (79.4%), puberty (77.0%), contraception (76.1%), and menstrual problems (73.5%). Topics least often cited as adequately covered included psychological testing (16.1%), violence in relationships (20.0%), violence and weapon-carrying (29.7%), and sports medicine (29.7%). Fifty-eight percent of 137 respondents thought that all or nearly all of their residents were competent in perform-ing pelvic examinations by the end of trainperform-ing; there was no difference between perceived competence and the residents’ use of procedure books. Seventy-four percent

used a specific curriculum for teaching AM; materials included chapters/articles (85%), lecture outlines (76.1%), slides (41.9%), videos (35.5%), written case studies (24.5%), computerized cases (6.5%), and CD-ROMs (3.2%). Fifty-two percent usedBright Futures, 48% used the Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services, and 14% used the Guide to Clinical Preventive Servicesfor teaching clinical preventive services. Programs that used

Bright Futures were more likely to feel that preventive services were adequately covered in their programs than those who did not (78% vs 57%). A majority of programs desired more learner-centered materials.

Conclusions. Although almost all pediatric programs are now providing AM rotations, there is significant vari-ability in adequacy of training across multiple topics important for resident education. Programs desire more learner-centered materials and more faculty to provide comprehensive resident education in AM. Pediatrics

1998;102:588 –595;pediatric residency training, adolescent medicine, medical education, clinical preventive services, pelvic examinations.

ABBREVIATIONS. STD, sexually transmitted diseases; GAPS, Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services; AAP, American Acad-emy of Pediatrics; RRC, Residency Review Committee; AM, ado-lescent medicine; Med/Peds, Medicine/Pediatrics.

A

dolescents in the United States have high rates of morbidity and mortality stemming from intentional and nonintentional injuries, depression, substance abuse, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), including human immunodefi-ciency virus infection, and unplanned pregnancies. Improving the delivery of clinical preventive services to adolescents and the training of primary care pro-viders in adolescent health have been identified as mechanisms to help address some of these public health problems. New health supervision guidelines includingGuidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services (GAPS),1Bright Futures: Guidelines for HealthSupervi-sion of Infants, Children and Adolescents,2 and the

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Guidelines for Health Supervision III3have been published in the

past 5 years. To improve residency training, the Am-bulatory Pediatric Association published curricular goals and objectives for residency programs.4A

com-pendium,Adolescent Medicine: Residency Training Re-sources,5 was distributed to residency training

pro-grams in 1996 to help propro-grams comply with the 1997 Residency Review Committee (RRC) guidelines From the *Divisions of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine and ‡General

Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; the §Department of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts;iHarbor UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California; and the ¶Office of Educational De-velopment, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

Presented in part at the Society on Adolescent Medicine, March 6, 1998, Atlanta, GA.

Received for publication Jan 2, 1998; accepted Mar 5, 1998.

Reprint requests to (S.J.E.) Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine, Children’s Hospital, 300 Longwood Ave, Boston, MA 02115.

requiring a 1-month block rotation in adolescent medicine (AM).

The need for specific training in AM is not a recent phenomena. J. Roswell Gallagher in 1957 called for enhanced pediatric education in adolescent medi-cine6:

“The inclusion of care of adolescents in pediatric education offers a unique opportunity to acquire skill in combining an understanding of a patient’s characteristics and needs with a knowledge of his disorder when planning his management and care . . . If one doesn’t—if one treats only his illness and disregards him— he will ignore advice, break his next ap-pointment, lose his pills, or break his brace . . . ”

In 1978, the Task Force on Pediatric Education7

declared that “The health needs of adolescents are being inadequately met. Pediatrics should now take upon itself the full responsibility for improving the health care and research for this segment of the American population . . . There should be increased emphasis on the biosocial aspects of pediatrics and adolescent health.” Two years later, Michael Cohen, a member of the Task Force, provided specific guid-ance for the implementation of a curriculum in AM for pediatric residency programs, including develop-mental, medical model, and multidisciplinary ap-proaches.8

In a 1983 survey of pediatric residency programs, Comerci and colleagues9reported favorable trends in

a number of indicators after the Task Force Report was published. They noted a 10% increase in AM wards, a 33% increase in AM clinics, a 29% increase in programs having a block devoted to AM, an in-crease in adolescent inpatients and outpatients served, and increased mastery of curricular objec-tives. In contrast, in a survey of 46 programs, Wein-berger and Oski10found little change from before to

after the Task Force Report was published; less than half of the programs had a required AM rotation before (12/29) or after (14/29 in 1983) the report was published.

Despite curricular changes in some training pro-grams and residents’ avowed intent to provide health care for teens, pediatric residents have shown low self-assessed competency in many areas of AM, including pelvic examinations and contraceptive and substance abuse counseling.11,12Surveys of practicing

pediatricians revealed similar deficiencies in self-as-sessments of skills13–16with most studies finding little

change even for those who were more recent grad-uates of residency programs. In the survey by Chastain and colleagues,14members of the AAP

Sec-tion on Adolescent Health were more likely to pro-vide gynecologic examinations and contraceptive counseling than other pediatricians, but much of the training had occurred postresidency in fellowship programs or continuing education courses. A 1989 survey of 3000 pediatricians by Wender and col-leagues17 found that many believed their training

was insufficient although those graduating in the past 5 years were less likely to consider their training in AM insufficient (50.9%) than earlier graduates (59.1%). Studies based on self-assessment of skills by residents or pediatricians, however, have limitations in demonstrating the effect of training on skills. Only

a few small studies have examined the effect of train-ing on improvement in actual skills. Rabinowitz, Neinstein, Slavin and others have demonstrated that structured AM rotations can increase skills in pelvic examinations, interviewing, and psychosocial assess-ments.18 –20

Today, pediatric residency programs face new training challenges including teaching about a myr-iad of topics in adolescent health, using newer prin-ciples of adult learning,21–23 responding to the RRC

requirement of the 1-month block rotation in AM, and providing sufficient faculty resources in a time of increasing economic constraints on academic health centers. The objectives of this study were to assess progress in meeting these challenges and to determine current teaching methodology and ade-quacy of curricula and faculty in teaching AM in pediatric residency programs in the United States.

METHODS

A new Pediatric Residency Program Survey was developed with input from experts in pediatric training and medical educa-tion, preventive services, AM, and behavioral pediatrics. Two members of the current Task Force on the Future of Pediatric Education, two Fellows who had just completed chief residencies in pediatrics, and three pediatricians gave further invaluable con-tributions. The survey was pilot-tested to assure that questions were clearly worded and to determine the time needed for com-pletion.

The 9-page 92-item survey consisted of three sections: a Resi-dency Program Director Survey, a Behavioral Medicine Survey, and an Adolescent Medicine Survey. Only the Program Director and Adolescent Medicine Surveys are discussed here. The Resi-dency Program Director Survey included questions about the person answering the survey and his/her position, the structure of AM within the department of pediatrics, the locations of resident training, the total number of PL1– 4 residents including separate columns for categorical and primary care residents, the total num-ber of Medicine/Pediatrics (Med/Peds) residents rotating through the program each year, the existence and duration of a block rotation in AM and whether it was required, the presence of a rotation through an inpatient AM service, texts and materials being used for teaching clinical preventive services, use of the Bright Futures text in continuity clinics, use of substance abuse curricula, desire for additional resources in and barriers to teach-ing about substance abuse, and the use of curricula in racial/ ethnic diversity.

The Adolescent Medicine Survey included questions about the person completing the form, the presence of formal curricula in AM, curricular materials currently being used in teaching AM and what resources the program would find helpful in their program, the frequency of use of materials scored on a 5-point scale from never to very frequently, the location of clinical settings for resi-dents in AM scored from never to very frequently, the number of pediatric residents believed to be competent in performing routine pelvic examinations for sexually active adolescent girls scored on a 5-point scale from none to all, the use of a procedure book for residents to record the number of pelvic examinations, the faculty responsible for supervising residents in their clinical work, and the adequacy of current faculty (“Do you have an adequate num-ber of faculty in your department to provide excellent AM training for your residents?”). Programs were also given a list of 24 topics in AM and asked “Please tell us what AM topics you feel are currently covered adequatelyin your residency program (please check all that apply).”

or Behavioral Pediatrics be mailed to increase resources for resi-dency programs. The survey was mailed in January 1997 to all programs identified by mailing labels from the Association of Pediatric Program Directors. An instructional video in pelvic ex-amination was offered as an incentive for completion; reminder telephone calls were made if surveys were not returned within 3 months. Forms were refaxed or mailed to programs that could not locate their forms. Ten programs names on the mailing list were duplicates. Five residency directors and seven AM directors re-turned two forms as a result of the first duplicate or second follow-up mailing; the first form only is included in the data analysis.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 6.1 statistical software (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL, 1993). Categorical variables were analyzed using Pearson x2 or Fisher’s exact tests if expected values were ,5.

Grouped comparisons of ordinal variables were analyzed using Mann-WhitneyUtests for those with distributions that were not normally distributed andttests for variables that were normally distributed.

RESULTS

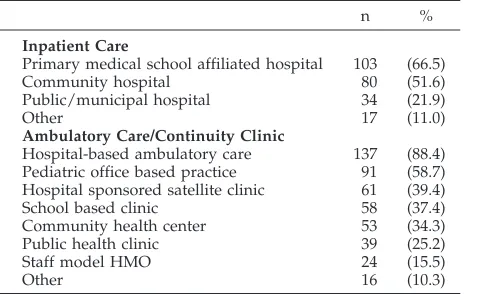

One hundred fifty-five of 211 (73.5%) programs responded to both the Residency Program Director Survey and the Adolescent Medicine Survey, with 123 (79%) of the Residency Program Director Survey completed by the residency director and the other 21% completed by the chief resident or residency coordinator. The Adolescent Medicine Survey was completed by residency director in 51 (32.9%) and by the director of AM in 88 (56.8%). Programs trained between 5 and 120 PL1-PL3 residents and between 0 and 52 Med/Peds residents. The responding pro-grams had a separate Division of Adolescent Medi-cine in 70 (45.2%), a combined Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine (or Ambulatory Pediatrics) in 72 (46.5%), and some other structure in the remaining programs. Sixty programs (38.7%) felt that there were adequate numbers of faculty in their department to provide excellent AM training. Resi-dents trained in a variety of settings (Table 1), in-cluding pediatric office practices, school-based clin-ics and community health centers. Locations of the rotations included urban (85%), suburban (61.3%), and rural (25.2%).

Of the 155 programs, 149 (96.1%) had a block rotation in AM with 143 (92%) having a duration of 4 or more weeks and 139 (89.7%) having a required block rotation. One hundred eleven (71.6%) had res-idents rotating through an inpatient adolescent med-ical service. Those without a block rotation were

more likely to have a higher total number of pediat-ric residents (P 5 .026). When the Med/Peds resi-dents were added to the total number of resiresi-dents, the association between program size and having a block rotation in AM became not statistically signif-icant but trended in the same direction (P 5 .068). Overall, 48.9% of programs had Med/Peds residents. Training Med/Peds residents was not significantly associated with having an AM block (P 5 .087). Three of the four programs without a block rotation that answered the question assessing adequacy of AM faculty reported adequate faculty. In fact, among the 60 programs reporting adequate faculty, those without a block rotation were still more likely to be larger programs (P5.017). Faculty supervising res-idents are noted in Table 2. There was no difference between programs with adequate and those without adequate AM faculty in the inclusion of either nurse-practitioners alone to teach or the inclusion of all non-MD professionals (including nurse practitio-ners) to teach residents. An AM clinic was the site most likely to be used frequently or very frequently in resident training (Table 3).

Bright Futures was used by 81 (52.2%) programs,

GAPS was used by 75 (48.4%), the Guide to Clinical Preventive Services24was used by 21 (13.5%),Put

Pre-vention Into Practice25 was used by 7 (4.5%), and 20

(12.9%) used other texts or resources for teaching clinical preventive services; 112 (72.3%) were using

GAPS, Bright Futures, or both. Overall, 111 (71.6%) programs were familiar withBright Futures; 62/111, (56.9%) reported that interns had a copy of Bright Futures; and 83/111 (75.5%) had a copy of Bright Futures as a resource in the conference room or li-brary. Seventy-two of the 111 (65%) were using

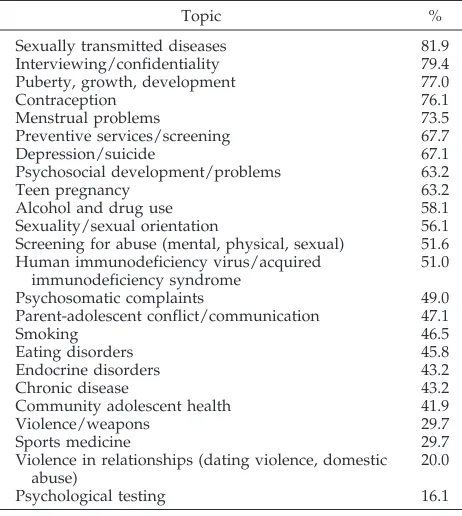

Bright Futuresin the continuity clinic, almost half of whom (48%) used it occasionally to very frequently. A formal curriculum in AM was reported by 115 (74.2%) programs but varied from a single page or outline to more extensive readings and case confer-ences. Proportions of programs believing that vari-ous topics in AM were being adequately covered are presented in Table 4. Most programs felt that STDs, interviewing, and puberty were adequately covered, and fewer believed that training in chronic disease, violence, and sports medicine was adequate. Three factors were associated with the belief that preven-tive services were adequately covered in the resi-dency program: use ofBright Futuresas a text in the residency program, use of this text for teaching in continuity clinic, and increased frequency of Bright

TABLE 1. Locations in Which Residents Receive Training in Ambulatory and Inpatient Pediatrics

n %

Inpatient Care

Primary medical school affiliated hospital 103 (66.5)

Community hospital 80 (51.6)

Public/municipal hospital 34 (21.9)

Other 17 (11.0)

Ambulatory Care/Continuity Clinic

Hospital-based ambulatory care 137 (88.4) Pediatric office based practice 91 (58.7) Hospital sponsored satellite clinic 61 (39.4)

School based clinic 58 (37.4)

Community health center 53 (34.3) Public health clinic 39 (25.2)

Staff model HMO 24 (15.5)

Other 16 (10.3)

TABLE 2. Faculty Supervising Residents in Their Clinical Adolescent Medicine Training Programs

n %

Adolescent medicine specialist 121 (78.1) General pediatrician 90 (58.1)

Nurse practitioner 44 (28.4)

Psychologist 39 (25.2)

Teaching resident/fellow 30 (19.4)

Social worker 29 (18.7)

Psychiatrist 28 (18.1)

Internist 11 (7.1)

Futures use. Seventy-eight percent of those using

Bright Futures as a text felt that preventive services were adequately covered, compared with 57% of programs who were not using this text (P 5 .007). Among those using Bright Futuresto teach in conti-nuity clinic, 79% believed preventive services were adequately covered versus 54% not using it (P,.01). For those usingGAPS alone as a text, there was no difference in the belief that preventive services were adequately covered (71% vs 65%;P5.45). However, when looking at programs using GAPS and/or

Bright Futures compared with those using neither, adequacy of preventive services coverage was again judged higher by the former group (72% vs 56%;P5

.049). Those programs that believed preventive ser-vices were adequately covered used Bright Futures

more frequently than those programs that believed preventive services were not adequately covered (mean, 3.160.8 vs 2.660.9;P5.005). The findings regarding the use ofBright Futuresand/orGAPSalso held when the data was analyzed looking only at those programs in which a different individual an-swered the Residency Program Director Survey that assessed Bright FuturesandGAPSuse and the Ado-lescent Medicine Survey that assessed adequacy of coverage of preventive services.

The majority of respondents (76.1%) were using curricula to teach about substance abuse in adoles-cents; however, fewer programs had resources to teach about substance abuse by parents/caregivers (27.1%) or by health professionals (23.2%). However, over 85% of those without curricular materials in these areas felt that these subjects should be covered. Of all programs, 83.9% desired additional materials for teaching about substance abuse in adolescents, 84.5% about substance abuse by parents/caregivers, and 74.5% about substance abuse by professionals. Barriers to teaching substance abuse included lack of time in 83 (53.5%), lack of curricula in 65 (41.9%), and lack of faculty in 66 (42.6%). Programs using a cur-riculum in substance abuse were more likely to feel that alcohol and drug use was adequately covered for residents than those without curricula (63% vs 38%;P5.0005). Only 36 programs (23.2%) had cur-ricular materials that addressed issues of racial/eth-nic diversity.

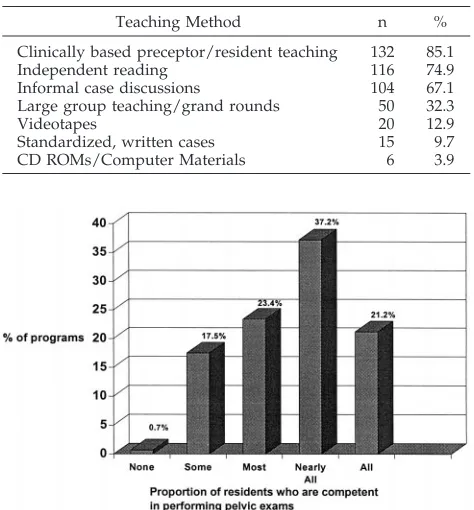

The materials currently being used to teach AM and those for which additional resources are needed are listed in Table 5. Of note, most programs are using lecture outlines, review/articles, and book chapters and would not find additional resources in these areas useful. In contrast, interactive resources were less available and highly desired. As noted in Table 6, methods most commonly used to teach AM include informal case discussions, clinically based preceptor/resident teaching, and independent read-ing.

Fifty-two percent of the 155 programs responded that nearly all to all of their residents were competent in pelvic examinations for sexually active teens (Fig 1). Residents recorded pelvic examinations in a pro-cedure book in 45 (29%) programs. There was no difference between programs that did or did not use procedure books and perceived competency of resi-dents in pelvic examination.

TABLE 3. Clinical Practice Settings in Which Residents Get Experience “Frequently” or “Very Frequently” With Adolescent Patients

Site n %

Adolescent medicine clinic 111 71.6 General pediatrics continuity clinic 65 41.9 Adolescent inpatient ward 60 38.7

School-based clinic 42 27.1

University health services 28 18.1 Juvenile detention center 10 6.5

TABLE 4. Percent of Pediatric Residency Programs Who Feel That Adolescent Medicine Topics areAdequatelyCovered

Topic %

Sexually transmitted diseases 81.9 Interviewing/confidentiality 79.4 Puberty, growth, development 77.0

Contraception 76.1

Menstrual problems 73.5

Preventive services/screening 67.7

Depression/suicide 67.1

Psychosocial development/problems 63.2

Teen pregnancy 63.2

Alcohol and drug use 58.1

Sexuality/sexual orientation 56.1 Screening for abuse (mental, physical, sexual) 51.6 Human immunodeficiency virus/acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome

51.0

Psychosomatic complaints 49.0

Parent-adolescent conflict/communication 47.1

Smoking 46.5

Eating disorders 45.8

Endocrine disorders 43.2

Chronic disease 43.2

Community adolescent health 41.9

Violence/weapons 29.7

Sports medicine 29.7

Violence in relationships (dating violence, domestic abuse)

20.0

Psychological testing 16.1

TABLE 5. Materials Used to Teach Adolescent Medicine and Need for Additional Resources

Programs Currently Using These Resources

Programs Would Find Additional Resources Helpful

n (%) n (%)

Review articles/book chapters 132 (85.0) 4 (2.6)

Lecture outlines 118 (76.1) 11 (7.1)

Slide sets 65 (41.9) 59 (38.1)

Videos 55 (35.5) 69 (44.5)

Standardized, written cases for group discussion 38 (24.5) 90 (58.1)

Self-administered computerized cases 10 (6.5) 100 (64.5)

DISCUSSION

In the 20 years since the publication of the Task Force Report,7numerous surveys and commentaries

have suggested that residents and practicing pedia-tricians have deficiencies in their knowledge and skills in caring for adolescent patients.9,11–17,26 –28. This

study suggests that while residency programs ap-pear to have made major changes in response to today’s health care challenges and the new RRC requirements, major educational needs persist. Many programs are seeking additional curricular materials, indicating a need for the creation of new materials and resources. Although the number of programs with separate AM sections (45%) has changed little from the Comerci survey of 1983 (50%), the number of programs with a block rotation in AM has dra-matically increased. Comerci and colleagues re-ported that the number of programs with a required block rotation increased from 32% in 1978 to 58% in 1983. In this 1997 survey, 97% of programs offered a block rotation, and 90% of programs required the block. Of note, the four programs not offering a block rotation were larger programs. It is possible that the logistics of major changes in large programs, includ-ing the provision of clinical experiences for large numbers of residents in an ambulatory setting with adequate numbers of patients or the need to fulfill service requirements in inpatient settings are partic-ularly problematic. Because three of these four pro-grams indicated that they had adequate faculty, shortage of teaching faculty does not appear to ex-plain the difference observed on the basis of program size.

Adequacy of faculty to teach AM had not been addressed in previous surveys. In this survey, we found that only 39% of programs reported adequate numbers of faculty for teaching excellent AM. In many programs, nonpediatrician faculty including nurse practitioners, social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists and others are providing teaching to residents. The use of non-MD faculty was not asso-ciated with adequacy of available AM faculty to train residents. It is unknown whether these interdiscipli-nary faculty are recruited because of the recognized multidisciplinary needs of adolescents, the diverse sites in which residents provide clinical care (eg, school-based clinics), a shortage of AM faculty, or insufficient financial resources to recruit AM faculty to enhance teaching. Further study of manpower requirements and interdisciplinary resources are needed because increasing numbers of primary care residents desiring AM training may put further de-mands on AM clinical settings and faculty and po-tentially compromise continuity of care for adoles-cent patients. Whether new fellowship requirements for AM subspecialists will decrease available faculty also needs to be assessed.

The extent to which hospitals and training pro-grams have increased or decreased the use of inpa-tient AM wards over the past 20 years also is not known. The previously reported numbers of training sites with inpatient AM wards have ranged from 41% to 46%9(Blizzard RM. Training of pediatric

res-idents in adolescent medicine. Memorandum to pe-diatric department chairman, March 14, 1978). In this survey, .70% of program directors reported that residents rotated through an inpatient AM service, but only 39% of respondents to the AM section listed an AM inpatient ward as a clinical setting in which residents frequently or very frequently received ex-perience with adolescent patients. Shortened length of stay in hospitals and fiscal constraints have re-cently called into question age-based services that in the past have facilitated adolescent specific care and provided an additional opportunity for teaching res-idents about adolescents with chronic illness. Further study is needed to assess benefits of these services to patients, families, and residency training and whether other inpatients services such as psychiatric wards, detention centers, or residential settings might provide additional training experiences.

The number of curricular objectives felt to be op-timal to enhance competency in the field of AM has dramatically increased from the time of the Comerci survey to the publication of the 1996 Ambulatory Pediatric Association Educational Guidelines. Programs today are expected to teach about many new or recently recognized morbidities (eg, violence, do-mestic abuse) and to expand the number of topics covered. Residents have low self-perceived compe-tencies in a number of areas, particularly gynecologic care and contraceptive and substance abuse counsel-ing.12 The current study reveals that topics most

likely to be felt by programs to be adequately cov-ered included STDs, confidentiality, puberty, contra-ception, and menstrual problems with slightly lower percentages for preventive services, depression, psy-TABLE 6. Percent of Residency Programs Using the

Follow-ing Methods “Frequently” or “Very Frequently” in TeachFollow-ing Adolescent Medicine

Teaching Method n %

Clinically based preceptor/resident teaching 132 85.1

Independent reading 116 74.9

Informal case discussions 104 67.1 Large group teaching/grand rounds 50 32.3

Videotapes 20 12.9

Standardized, written cases 15 9.7 CD ROMs/Computer Materials 6 3.9

chosocial problems, and teen pregnancy. Topics that were least likely to be adequately covered included violence in relationships, violence and weapon-car-rying, and, surprisingly, sports medicine. Only about half of the programs felt that important topics such as screening for abuse, human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, smok-ing, eating disorders, and parent/adolescent con-flict/communication were adequately covered. Al-though most programs taught about substance abuse, many programs did not feel the subject was adequately covered and desired further curricular materials.

Approximately two-thirds of programs felt that clinical preventive services were adequately covered by their training curriculum. About half of the pro-grams were usingBright Futuresand a similar num-ber were using GAPS, and 70% were using one or both of these resources. TheGuide to Clinical Preven-tive Services24appears to be less well-known to

pedi-atric programs. Our data indicate that programs us-ing Bright Futures were more likely to feel that preventive services were adequately covered in their programs than those who were not using this text. How Bright Futures is used in these programs and why this resource and not GAPS alone was associ-ated with a greater likelihood that programs would feel preventive services are adequately covered are unknown. The trigger questions provided byBright Futuresmay be particularly helpful as residents try to formulate actual implementation of preventive guidelines. In addition, the small number of pro-grams using justGAPSmay have limited our power to show statistical significance when observing the associations between GAPSand preventive services coverage. We did not ask about the use of theGAPS Clinical Evaluation and Management Handbook,29which

provides clinical algorithms and extensive interview questions or the use of theGAPSquestionnaires.30It

is thus unknown if programs were referring only to theGAPSmonograph with the 24 recommendations or other materials that would enhance teaching and clinical application. It is also possible that because the survey was sponsored by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, programs would perceive that if they usedBright Futuresthey should give responses sug-gesting that preventive services were adequately covered. However, only 50% of programs were using

Bright Futuresand only 71% were familiar withBright Futures. In addition, when observing only the pro-grams that had different people completing the Res-idency Program Director Survey, which included questions about Bright Futures, and the Adolescent Medicine Survey, which included the questions about adequacy of curricula, were analyzed, the same findings held.

The importance of residents learning how to per-form pelvic examinations to provide clinical preven-tive services and to evaluate pelvic and abdominal symptoms in adolescent girls has been emphasized over the past two decades.14 –16Using a 5-point Likert

scale of self-perceived competency in pelvic exami-nations, Chastain and colleagues14 reported that

more recent graduates (1976 –1985) believed that

they were more competent in pelvic examinations that those graduating before 1976 but the mean rat-ing was still relatively low (2.65). Neinstein15

re-ported that 68% of Los Angeles pediatricians rated their competence in the pelvic examinations as aver-age or below averaver-age. In this study, 58% of the 137 programs responding to the question regarding com-petency in pelvic examinations thought that nearly all to all of their residents were competent in pelvic examinations, and slightly.80% felt that most to all of their residents were competent in pelvic examina-tions. Although how programs define competent is not clearly determined, these data suggest that more programs are teaching gynecologic care to pediatric residents with expectations for their achieving com-petency. Procedure books used by almost one third of programs for recording pelvic examinations may help program directors assess whether residents are actually performing sufficient numbers of pelvic ex-aminations throughout their training in the AM ro-tation, emergency ward, and other clinical sites. Bar-riers to teaching gynecologic examinations to pediatric residents include the impact of inexperi-enced examinations on patient satisfaction, the im-pact of recent guidelines about the involvement of attendings in repeating examinations, time con-straints in busy clinics, and preferences of patients for a female examiner. Innovative teaching tech-niques are needed to meet curricular objectives in gynecology and may include videotapes, live models for pelvic examination teaching, and structured teaching with direct feedback from attending level physicians and nurse practitioners on actual skills of performing pelvic examinations.18,20

This survey found that ambulatory care/continu-ity clinics for residents frequently occurred outside of hospital-based centers including pediatric offices (59%), school-based clinics (37%), and in community health centers (34%). As more residents receive am-bulatory training in pediatric offices, residency pro-grams need to assess in which sites modeling gyne-cologic care and skills as well as general skills of adolescent health care can be accomplished. Given the surveys of pediatricians’ self-assessed compe-tency and their busy office schedules, block rotations in AM remain particularly important to assure that curricular goals and objectives are met and that ad-equate structured teaching is provided by AM fac-ulty including interview techniques, the establish-ment of a rapport with teens and their families, and psychosocial assessment.18,20Expanding clinical sites

to college health (reported by 18% of programs), health maintenance organizations, school-based clin-ics, and clinics that serve youth who are homeless, incarcerated, or in foster care will benefit residents, but the need for adolescents to have continuity of care cannot be overstated. Because adolescents may have only one visit per year, designing a program for longitudinal care within a resident’s schedule is a particular challenge and dependent on incorporating some principles of AM training into the continuity clinic experience.

train-ing of physicians. Techniques such as problem-based tutorials, lectures, and laboratory exercises have be-come more common in medical school curricula.21–23

In the Comerci survey, teaching methodologies in-cluded clinical outpatient teaching (42%), small group conferences on interview techniques (42%), self-instructional materials (30%), and videotapes (28%). Our data indicated that 74% of programs were using a specific curriculum (often only a single page of objectives). Teaching materials included predom-inantly chapters/articles and lecture outlines. Clini-cally based preceptorships, informal case-based teaching, and independent reading were the most frequently used methods for teaching AM. Although much research has examined medical student expe-riences, less is known about how to maximize resi-dent learning, especially in ambulatory rotations that are not linked to bedside teaching and morning at-tending rounds.31,32 In this survey, residency

pro-grams overwhelmingly desired learner-centered ma-terials over additional books and outlines, suggesting the need for further curricular develop-ment and the incorporation of the principles enumer-ated in the Adolescent Medicine: Residency Training Resources.5 The data also suggest significant gaps

between available resources and those methods shown in studies of medical student learning to re-sult in more acquisition of knowledge and skills. Although not a specific goal of this project, future research on measurable methods of evaluation be-yond faculty and resident self-assessment is needed to promote skills and knowledge.

There are a number of limitations in this study. Although the response rate was significantly better than the survey by Comerci and colleagues,9we do

not have information on 25% of programs. In the Comerci survey, programs responding had higher rates of block rotations and AM clinics than nonre-sponders, and thus our survey may have overesti-mated the number of programs providing block ro-tations. In addition, busy faculty and chief residents completing surveys may have had variable knowl-edge of the program. Their responses may not rep-resent the true adequacy of curricular coverage of materials or the real competency of residents in areas such as pelvic examinations. We did, however, en-courage the most knowledgeable person to complete the forms and provided multiple stamped envelopes to assess curricula and program objectives. The pro-gram director completed almost 80% of the Resi-dency Program Director Surveys and the director of Adolescent Medicine, completed almost 57% of the Adolescent Medicine Surveys. The questions were worded to allow programs to feel that residents did not need to have adequate curricula on all the topics in the list.

CONCLUSION

This survey found that although a large number of pediatric training programs are meeting the new RRC requirement for a block rotation in AM, many desire more knowledge of available resources and techniques of training. Structured goals and objec-tives combined with clinical teaching methodology

and skills must take into account the constraints of time in the daily lives of residents and their faculty teachers,32 and yet have the potential to be

imple-mented across programs. Written case-based materi-als and interactive Web- and computer-based clinical scenarios that foster decision-making are resources urgently in need of further development and dissem-ination. Ongoing and updated cataloguing of re-sources for all programs, development of evaluation techniques that will allow programs to do more crit-ical self-appraisals, and surveys of residents and pe-diatricians trained in the new block rotations are additional needs. As the AAP and other national groups set priorities, resources for curriculum devel-opment and dissemination of the materials should figure high in assisting the.200 programs training the next generation of pediatricians.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by Project MCJ 259368 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (Title V, Social Security Act), Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services.

We thank James Simon, MD, Russell Chesney, MD, Robert DuRant, PhD, Frederick Lovejoy, Jr, MD, Jonathan Finkelstein, MD, Estherann Grace, MD, Henry Bernstein, DO, Arthur Elster, MD, Christopher Reif, MD, MPH, MA, Richard Kreipe, MD, and Gwendolyn Gladstone, MD, for help in developing the question-naire; all the program directors and adolescent medicine faculty who responded so promptly and with urging to the survey; Laura Degnon (Association of Pediatric Program Directors) for the as-sistance with the mailing; and Ortho Pharmaceutical Corporation for the pelvic examination videotapes.

REFERENCES

1. American Medical Association Department of Adolescent Health.

Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services (GAPS).Chicago, IL: Amer-ican Medical Association; 1993

2. Green M, ed.Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents.Arlington, VA: National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health; 1994

3. American Academy of Pediatrics.Guidelines for Health Supervision III.

Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 1997 4. Kittredge D and APA Education Committee, eds.Ambulatory Pediatric

Association (APA) Educational Guidelines for Residency Training in General Pediatrics.McLean, VA: Ambulatory Pediatric Association; 1996 5. American Academy of Pediatrics, Section of Adolescent Health.

John-son J, ed.Adolescent Medicine: Residency Training Resources.Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 1995

6. Gallagher JR. Adolescent and pediatric education.Pediatrics.1957;19: 937–939

7. Task Force on Pediatric Education. Report on the Future of Pediatric Education.Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 1978 8. Cohen MI. Importance, implementation, and impact of the adolescent medicine components of the report of the Task Force on pediatric education.J Adolesc Health Care.1980;1:1– 8

9. Comerci GD, Witzke DB, Scire AJ. Adolescent medicine education in pediatric residency programs following the 1978 Task Force on pediat-ric education report.J Adolesc Health Care.1987;8:356 –364

10. Weinberger HL, Oski FA. A survey of pediatric resident training pro-grams 5 years after the Task Force report.Pediatrics.1984;74:523–526 11. Figueroa E, Kolasa KM, Horner RE, et al. Attitudes, knowledge, and

training of medical residents regarding adolescent health issues.J Ado-lesc Health.1991;12:443– 449

12. Slap GB. Adolescent medicine: attitudes and skills of pediatric and medical residents.Pediatrics.1984;74:191–197

13. Blum R. Physicians’ assessment of deficiencies and desire for training in adolescent care.J Med Educ.1987;62:401– 407

14. Chastain DO, Sanders JM, DuRant RH. Recommended changes in pe-diatric education: the impact on pepe-diatrician involvement in health care delivery to adolescents.Pediatrics.1988;82:469 – 476

health care training, skills, and interest.J Adolesc Health Care.1986;7: 18 –21

16. Key JD, Marsh LD, Darden PM. Adolescent medicine in pediatric practice: a survey of practice and training.Am J Med Sci.1995;309:83– 87 17. Wender EH, Bijur PE, Boyce WT. Pediatric residency training: ten years

after the Task Force report.Pediatrics.1992;90:876 – 880

18. Rabinovitz S, Neinstein LS, Shapiro J. Effect of an adolescent medicine rotation on pelvic examination skills of pediatric residents.Med Educ.

1987;21:219 –226

19. Slavin SJ, Anderson MM, Nyquist JG, et al. Improving the care of adolescents: an innovative curriculum for pediatrics residents.Acad Med.1992;67:S48 –50

20. Neinstein LS, Shapiro J, Rabinovitz S. Effect of an adolescent medicine rotation on medical students and pediatric residents.J Adolesc Health Care.1986;7:345–349

21. Armstrong EG. A hybrid model of problem-based learning. In: Boud D, Feletti G, eds.The Challenge of Problem Based Learning.2nd ed. London, England: Kogan Page Publishers; 1997:137–150

22. Glick TH, Armstrong EG. Crafting cases for problem-based learning: experience in a neuroscience course.Med Educ.1996;30:24 –30 23. Wetzel MS. Problem-based learning. An update on problem-based

learning at Harvard Medical School.Ann Comm Orient Educ.1994;7: 237–247

24. US Preventive Services Task Force.Guide to Clinical Preventive Services.

2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins; 1996

25. US Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service.

Clinician’s Handbook of Preventive Services. Put Prevention Into Practice.

Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1994 26. Biro FM, Siegel DM, Parker RM, Gillman MW. A comparison of self-perceived clinical competencies in primary care residency graduates.

Pediatr Res.1993;34:555–559

27. Strasburger VC. Pediatric residency training: time for a change.Clin Pediatr.1993;546 –547

28. Graves CE, Bridge MD, Nyhuis AW. Residents’ perception of their skill levels in the clinical management of adolescent health problems.J Ado-lesc Health Care.1987;8:413– 418

29. Levenberg PB, Elster AB.Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services. Clinical Evaluation and Management Handbook.Chicago, IL: American Medical Association Department of Adolescent Health; 1995 30. American Medical Association Department of Adolescent Health.

Im-plementation forms. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 1995 31. Neber JO, Gordon KC, Meyer B, et al. A five-step “microskills” model

of clinical teaching.J Am Board Fam Pract.1992;5:419 – 424

32. Zimmerman RK, Barker WH, Strikas RA, et al. Developing curricula to promote preventive medicine skills.JAMA.1997;278:705–711

AMERICANS CAN’T STOP BUYING STUFF

Schor JB.The Overspent American: Upscaling, Downshifting, and the New Consumer.New York, NY: Basic Books. $25. 253 pp (Illustrated.)

There must be a reason some Americans have so little sense of themselves that they buy a shirt emblazoned with Tommy Hilfiger’s phony coat of arms. There must be reasons they pay a premium for a designer lipstick instead of the anon-ymous equivalent at Walgreen’s, buy desert-ready Land Rovers to commute over asphalt, generate the world’s largest per capita volume of trash and, even in today’s lush job-rich economy, pack the bankruptcy courts.

It is not because they need this stuff (if “need” still means their lives depend on it). Thorstein Veblen attributed conspicuous consumption among the rich to be a desire to define social positions, and later James Duesenberry attributed it to “keeping up with the Joneses.” In The Overspent American, Juliet B. Schor, a Harvard economist, has identified a more recent variation of our materialism, an insidiously ruinous form of “competitive spending” and “competitive acquisition” that she calls “the new consumerism.”

DOI: 10.1542/peds.102.3.588

1998;102;588

Pediatrics

Berkowitz, Elizabeth Armstrong and Elizabeth Goodman

S. Jean Emans, Terrill Bravender, John Knight, Carolyn Frazer, Maria Luoni, Carol

Good Job?

Adolescent Medicine Training in Pediatric Residency Programs: Are We Doing a

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/102/3/588

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/102/3/588#BIBL

This article cites 20 articles, 5 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

icine_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/adolescent_health:med

Adolescent Health/Medicine

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/workforce_sub

Workforce

ev_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/teaching_curriculum_d

Teaching/Curriculum Development

ub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/career_development_s

Career Development

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.102.3.588

1998;102;588

Pediatrics

Berkowitz, Elizabeth Armstrong and Elizabeth Goodman

S. Jean Emans, Terrill Bravender, John Knight, Carolyn Frazer, Maria Luoni, Carol

Good Job?

Adolescent Medicine Training in Pediatric Residency Programs: Are We Doing a

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/102/3/588

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.