Infections in North Carolina NICUs

abstract

OBJECTIVE:Central lines in NICUs have long dwell times. Success in reducing central line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) requires a multidisciplinary team approach to line maintenance and insertion. The Perinatal Quality Collaborative of North Carolina (PQCNC) CLABSI project supported the development of NICU teams including parents, the implementation of an action plan with unique bundle elements and a rigorous reporting schedule. The goal was to reduce CLABSI rates by 75%.

METHODS:Thirteen NICUs participated in an initiative developed over 3 months and deployed over 9 months. Teams participated in monthly webinars and quarterly face-to-face learning sessions. NICUs reported on bundle compliance and National Health Surveillance Network infec-tion rates at baseline, during the interveninfec-tion, and 3 and 12 months after the intervention. Process and outcome indicators were analyzed using statistical process control methods (SPC).

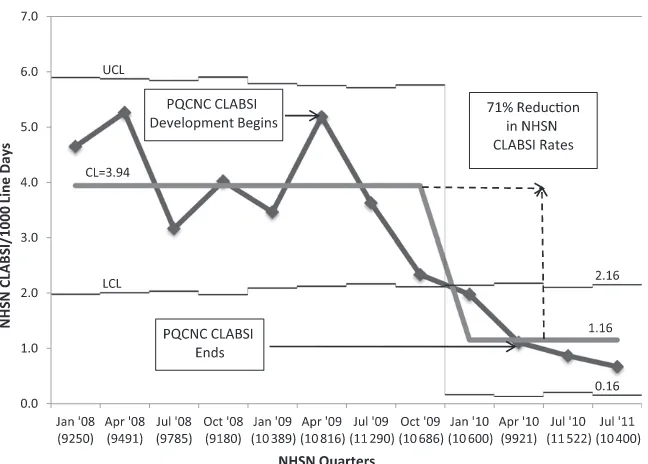

RESULTS:Near-daily maintenance observations were requested for all lines with a 68% response rate. SPC analysis revealed a trend to an increase in bundle compliance. We also report significant adoption of a new maintenance bundle element, central line removal when en-teral feedings reached 120 ml/kg per day. The PQCNC CLABSI rate de-creased 71%, from 3.94 infections per 1000 line days to 1.16 infections per 1000 line days with sustainment 1 year later (P5.01).

CONCLUSIONS:A collaborative structure targeting team development, family partnership, unique bundle elements and strict reporting on line care produced the largest reduction in CLABSI rates for any multi-institutional NICU collaborative.Pediatrics2013;132:e1664–e1671

AUTHORS:David Fisher, MD,aKeith M. Cochran, MA, MLT (ASCP), CABM(C), NPM, LSSBB, PMP,b Lloyd P. Provost, MS,c Jacquelyn Patterson, MD,bTara Bristol, MA,bKaren Metzguer, RN,bBrian Smith, MD, MPH, MHS,dDaniela Testoni, MD, MHS,dand Martin J. McCaffrey, MD, CAPT USN (Ret)b

aDepartment of Pediatrics, Levine Children’s Hospital at Carolinas

Medical Center, Charlotte, North Carolina;bDepartment of

Pediatrics, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina;cAssociates in Process Improvement,

Austin, Texas; anddDuke Clinical Research Institute, Durham,

North Carolina

KEY WORDS

quality improvement, central line–associated bloodstream infection, CLABSI, infant, family-centered care, enteral feeding

ABBREVIATIONS

CDC—Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CLABSI—central line–associated bloodstream infection LCL—lower control limit

LS—learning session

NHSN—National Health Surveillance Network PDSA—Plan Do Study Act

PQCNC—Perinatal Quality Collaborative of North Carolina QI—quality improvement

SPC—statistical process control VLBW—very low birth weight

Dr Fisher led the Perinatal Quality Collaborative of North Carolina (PQCNC) Central Line–Associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI) Expert Team, which developed the collaborative action plan. He was the principal speaker for 3 of 6 monthly webinars and led the 3 face-to-face learning sessions (LSs). He contributed to and reviewed manuscript development and assisted Dr McCaffrey in the primary drafting of the manuscript and in data analysis. Mr Cochran assisted in the development of the initial action plan outline. He was a member of the PQCNC CLABSI Expert Team, developed the data collection system for the project, was responsible for triaging questions and day-to-day support of teams participating in the collaborative, and contributed to and reviewed thefinal manuscript. Mr Provost was responsible for regularly reviewing data and analyzing outcomes and process indicators using statistical process control (SPC) analysis. His expertise in SPC was vital in delineating the impact of PQCNC CLABSI. He reviewed the manuscript and suggested revisions that were incorporated into thefinal manuscript. Ms Bristol was responsible for developing family participation at all levels in PQCNC CLABSI. She recruited family members from 4 centers to support the larger collaborative work. She identified and mentored families presenting at all LSs. She coproduced, in conjunction with Mr Cochran, the“Gabby”video, reviewed manuscript drafts, and made suggestions that were incorporated as revisions in thefinal manuscript. Dr Patterson was responsible for collecting and analyzing data for PQCNC CLABSI.

Central line–associated bloodstream in-fection (CLABSI) is a significant source of hospital morbidity and mortality. Quality improvement (QI) projects have attemp-ted to spread central line best practices in multiple clinical environments.1–4The

concept of bundles has developed, which defines compliance as an all or none phenomenon for all recommended-care elements. The most notable successes in CLABSI reduction have occurred in adult ICUs, where lines have shorter dwell times and the major emphasis has been on insertion bundles. Neonatal and pe-diatric central lines have longer dwell times, and line maintenance likely plays a critical role in the prevention of CLABSIs.5–7Miller et al clearly

dem-onstrated the importance of mainte-nance bundle compliance in PICUs and NICUs, but significant variation in cen-tral line care practice exists.8The

var-iable success in QI initiatives to reduce CLABSIs and nosocomial infection in PICUs and NICUs highlights the chal-lenges of developing best collaborative structures, supporting multidisciplin-ary hospital team formation, identify-ing best line care bundles, and trackidentify-ing compliance with those bundles.10–14

State collaboratives have gained increas-ing prominence in efforts to improve neonatal care and offer tremendous advantages as quality laboratories.15

Collaboratives offer the opportunity for shared learning. Although in large part due to payment, each state has de-veloped unique networks of care. Col-laboration amongst stakeholders within these unique laboratories offers the opportunity to improve care across the continuum of multiple systems. The Perinatal Quality Collaborative of North Carolina (PQCNC) aimed to unite these stakeholders in a collaborative offering hospital teams structured facilitation as they implemented and measured the deployment of insertion and mainte-nance bundles to reduce NICU CLABSIs for all infants by 75%.

METHODS

In March 2009 the PQCNC general membership identified NICU CLABSI prevention as a statewide initiative. A general proposal for a PQCNC CLABSI project was approved. A neonatologist volunteered to lead the CLABSI Expert Team in developing the PQCNC CLABSI action plan. The action plan would in-clude an aim statement, insertion and maintenance bundles, and process and outcome metrics that would guide hospitals in efforts to reduce CLABSIs for all infants in all types of NICUs. The expert team was composed of PQCNC members who reviewed background materials and attended webinars in which the action plan would be de-veloped.16,17In March of 2009 an expert

team assembled that included neo-natologists, parents, nurses, neonatal nurse practitioners, and infection control specialists.

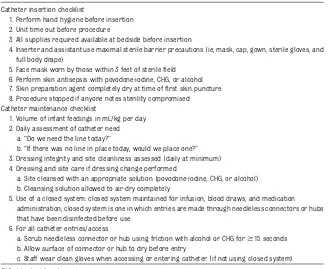

From April through June 2009, 3 expert team webinars were attended by 30 to 55 members. The expert team identified its primary goal as the reduction in CLABSIs by 75%. Insertion and mainte-nance bundles were developed, as well as process measures to reflect bundle adherence (Table 1). NICUs would be asked to report on process indicators for every line insertion. Maintenance indicators would be reported by staff for all lines for 7 shifts per week. In reporting maintenance indicators, cen-ters were required to include at least 1 weekend shift and 1 night shift per week. All NICU centers used 12-hour

nursing shifts. NICUs were free to es-tablish their own reporting schedule within these constraints.

The insertion bundle included recom-mended elements in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) line in-sertion guidelines as well as a“unit time out”(Table 2). The unit time out included checking patient identification and an-nouncing the procedure, the type of line to be inserted, and the site of line sertion. The maintenance bundle in-cluded CDC recommendations and 2 additional elements18:first was a

rec-ommendation that central lines be dis-continued when an infant’s enteral feedings reached 120 mL/kg per day; second was the requirement that teams evaluate lines daily with the added question,“If a line was not in place to-day, would one be placed?”

Enrollment and Roll Out

PQCNC CLABSI was approved at all site institutional review boards, or it was determined that the study was exempt from review. In June of 2009 PQCNC invited all hospitals in the state with an NICU and on-site neonatologist to join PQCNC CLABSI. Centers agreeing to par-ticipate formed an NICU team (recom-mended to include a neonatologist, nurse, executive leader, parent, and infection control specialist), obtained senior ex-ecutive support, reviewed the action plan, and received a start-up kit including guidance on implementation, data man-agement, and prework. Prework for the

first face-to-face learning session (LS)

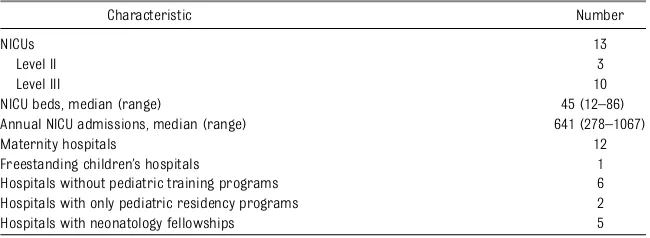

TABLE 1 Characteristics of PQCNC CLABSI NICUs

Characteristic Number

NICUs 13

Level II 3

Level III 10

NICU beds, median (range) 45 (12–86)

Annual NICU admissions, median (range) 641 (278–1067)

Maternity hospitals 12

Freestanding children’s hospitals 1

Hospitals without pediatric training programs 6 Hospitals with only pediatric residency programs 2

Hospitals with neonatology fellowships 5

included identifying an executive sponsor, formal review of 2 local CLABSI cases, and review of current line practice.

Three quarterly LSs were 1- to 2-day in-person events that included pre-sentations by teams and parents, data review, and QI education. Monthly 1-hour Web conferences were held and focused on staff engagement, NICU culture and leadership, progress reports, local Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) rapid-improvement intervention cycles, and sharing suc-cesses and challenges. Weekly e-mail newsletters supplemented key learning elements. Teams received data reports for all metrics on a quarterly basis.

Data and Analysis

The expert team identified process and outcome measures. The outcome measure identified for this initiative was CLABSIs per 1000 line days for all NICU patients. CLABSI during the in-tervention was defined by using CDC National Health Surveillance Network (NHSN) criteria. NHSN data for CLABSIs and line days were supplied by centers.

Any centers not participating in the NHSN would review hospital records to identify infections and report on line days on the basis of internal data. A Web-based commercial data entry system was identified (StudyTrax) to collect process measures. Process measures were elements of the insertion and maintenance bundles. These were ag-gregated. Insertion data were reported by a member of the team performing line insertion. Maintenance data were reported by bedside nurses engaged in patient care. All hospitals collected paper copies of data forms for later entry by a team member. Our data system would only accept forms with all bundle elements completed.

Statistical process control (SPC) charts were used to track process and out-come changes.19,20 For the primary

outcome of CLABSIs per 1000 line days, baseline NHSN data were obtained for the period January 2008 through Sep-tember 2009. The mean (center line) and upper and lower control limits (LCLs) were calculated and displayed

Redmond, WA). The mean was carried forward and displayed throughout the intervention (October 2009 through June 2010). Evaluation of the inter-vention occurred for 1 quarter after the intervention and 1 year later in July through September 2011 by using baseline data for PQCNC CLABSI NICUs entering a national CLABSI project.

There were no baseline data for process measures, and compliance measures were limited to 9 points. SPC guidelines suggest a minimum of 12 data points to determine significant changes in con-trol limits on the basis of trends of$7 points, but that would not limit our ability to detect signals of change and draw conclusions.

Adjustments to control limits were made by using SPC guidelines including 1 point outside the upper control limits or LCLs, 2 of 3 successive points in the outer third of the control limit, 8 successive points above or below the center line, or 6 consecutive points on an increasing or decreasing trend line.20

RESULTS

Thirteen NICUs participated in PQCNC CLABSI. Their characteristics are pre-sented in Table 1. Ten of the 13 centers were reporting NHSN data from January 2008 onward. The other 3 centers were lower volume NICUs with a mean of 105 line days per quarter. Chart and laboratory review at these centers from January 2008 through September 2009 revealed no infections based on NHSN criteria. At the time of PQCNC CLABSI initiation in October 2009, all centers were reporting NHSN data.

During the intervention period, there were 1308 line insertions reported. The majority of NICUs chose to report matenance activities for all weekdays, in-cluding 1 night, and for 1 weekend shift. This regimen represented a maximal opportunity to report on line maintenance

1. Perform hand hygiene before insertion 2. Unit time out before procedure

3. All supplies required available at bedside before insertion

4. Inserter and assistant use maximal sterile barrier precautions (ie, mask, cap, gown, sterile gloves, and full body drape)

5. Face mask worn by those within 3 feet of sterilefield 6. Perform skin antisepsis with povodone-iodine, CHG, or alcohol 7. Skin preparation agent completely dry at time offirst skin puncture 8. Procedure stopped if anyone notes sterility compromised Catheter maintenance checklist

1. Volume of infant feedings in mL/kg per day 2. Daily assessment of catheter need

a.“Do we need the line today?”

b.“If there was no line in place today, would we place one?” 3. Dressing integrity and site cleanliness assessed (daily at minimum) 4. Dressing and site care if dressing change performed

a. Site cleansed with an appropriate solution (povodone-iodine, CHG, or alcohol) b. Cleansing solution allowed to air-dry completely

5. Use of a closed system: closed system maintained for infusion, blood draws, and medication administration; closed system is one in which entries are made through needleless connectors or hubs that have been disinfected before use

6. For all catheter entries/access

a. Scrub needleless connector or hub using friction with alcohol or CHG for$15 seconds b. Allow surface of connector or hub to dry before entry

c. Staff wear clean gloves when accessing or entering catheter (if not using closed system)

6 days per week. Maintenance reports were received for 17 801 line days. There were a total of 30 587 catheter days reported during the intervention. On the basis of a maximal number of mainte-nance reports of 26 217, we achieved a response rate of 68%.

Insertion and maintenance bundles were analyzed for all or none compli-ance. Baseline insertion compliance was relatively high at 76%, peaked at 93%, and showed an overall trend to in-creasing insertion compliance (Fig 1). Baseline maintenance compliance was initially low at 32% and ranged as high as 56%. There was a trend to an in-crease in answering“yes”to the query,

“If a central line were not already present one would be placed that day.” The maintenance bundle element of line removal when enteral feedings reached 120 mL/kg per day showed a significant change with reporting dropping con-sistently below the 3-sLCL. This special cause variation directs adjustment of control limits for this bundle element despite only 9 data points (Fig 2 A–C).

There were a total of 57 CLABSIs during the intervention. The primary outcome

measure, CLABSI rate, was evaluated by measuring changes in quarterly col-laborative CLABSI rates with a baseline starting in January 2008 and ending in July 2011. Twelve of 13 NICUs showed a reduction in CLABSI rates. The CLABSI rate for the collaborative showed a significant decline during the initia-tive. The mean was adjusted from a baseline mean of 3.94 infections per 1000 line days to a mean of 1.16 infec-tions per 1000 line days through July 2010, which was a reduction of 71% in the collaborative CLABSI rate (Fig 3). The CLABSI reduction was analyzed by us-ing Mann-WhitneyU test and was sig-nificant atP= .01.

DISCUSSION

PQCNC CLABSI used rigorous collabora-tive building efforts over a 12-month period to reduce CLABSIs by 71% in 13 North Carolina NICUs caring for 62% of North Carolina’s very low birth weight (VLBW) infants. To our knowledge, this is the largest CLABSI reduction ever re-ported by an NICU collaborative. Where-as insertion and maintenance bundle compliance showed clear indications of

improvement, the length of the in-tervention period limited our ability to definitively report that increased com-pliance with insertion and maintenance bundles led to the significant improve-ments we noted for CLABSI rates during the period. Despite this limitation, we speculate that the success of this ini-tiative relates to at least 4 factors.

First, formal education, training of hos-pital teams in QI, and shared learning were vital to PQCNC CLABSI success. The face-to-face LSs and webinars included QI education regarding the role of rapid cycles of change and PDSAs, parent pre-sentations, team time to discuss initiative execution, evaluation of culture and leadership, discussion of challenges, and sharing of innovations developed by teams. Innovations were achieved via in-tensive campaigns to apprise staff of the impact of CLABSI in their NICUs and target specific areas of practice using PDSA methodology. Examples of such inter-ventions included creation of g-charts reporting days between infection, de-ployment of line insertion carts, family members monitoring provider hand hy-giene, using videography to spread the concept of the infant’s sterile “sacred space,” spreading methods to ensure that line hubs were properly scrubbed, role-playing unit time outs, and stealth assessments of practice by local NICU teams.

Second, PQCNC CLABSI required forma-tion of committed teams that regularly interacted with the purpose of in-creasing compliance with insertion and maintenance bundles. Daily reporting by bedside providers on adherence to maintenance bundle elements has not been reported previously and required engagement of multiple providers. We required reporting for at least 1 week-end and 1 night shift to increase the likelihood that all nursing rotations would engage in the initiative. PQCNC CLABSI had as a short-term goal im-proving measured compliance with

FIGURE 1

Aggregate insertion bundle compliance during the course of the initiative. For each month, the total number of line insertion observations is reported in parentheses. CL, center line.

bundles as the initial step to incor-poration of bundles into practice. We believed bundle compliance reporting would represent true adherence, but speculated that rigorous documentation requirements would make best line care a daily focus for providers. Significant effort was required by teams to meet reporting goals. Observations were captured by the bedside nurse on paper forms with data later entered online. In an NICU with 300 line days per month, there was 7 hours of monthly data entry time. PQCNC CLABSI NICUs are to be lauded for a reporting rate of 68%.

Our measured maintenance compliance rates were lower than those reported by others.8,12,13We speculate that

large-scale anonymous reporting by bed-side nurses led to a more accurate estimate of bundle compliance than

higher estimates reported in other stud-ies. Whereas overall compliance rates for both insertion, and especially mainte-nance, showed improving trends, these trends did not achieve SPC significance. One limitation in establishing significance was our 9-month observation period. Based on the trend line and significant reduction in PQCNC CLABSI rates, a longer period of observation might have re-vealed a significant relationship between bundle compliance and CLABSI reduction. The significance of the actual data aside, centers confirmed that the process of bedside provider reporting was critical in daily engaging multiple bedside pro-viders in the initiative and contributed to the reduction in CLABSI rates.

Third, the inclusion of family members as expert team and local team members was critical in building powerful teams. Four

hospitals (30%) had a parent as a team member. At LSs and webinars these parents offered a unique perspective on CLABSI and the deployment of bundles. A powerful motivator was the “Gabby” video produced by a parent team mem-ber and PQCNC staff.21In“Gabby”a father

recounts the birth, life, and death by a methicillin-resistant staphylococcus au-reus (MRSA) CLABSI of his premature daughter, Gabby, in a PQCNC NICU.“Gabby” pointedly brings urgency to the case for NICUs to improve central line practices.

Fourth, the expert team based PQCNC CLABSI bundles on others’toolkits16–18but

no best evidenced recommendation for the point at which a central line should be discontinued in these cases, the ex-pert team identified enormous variation. Line removal was occurring at feeding volumes from 100 to 150 mL/kg per day in participating NICUs. The expert team agreed to standardize this practice and established a recom-mendation for line removal at enteral feedings of 120 ml/kg per day. There was a statistically significant adoption of this guideline. The expert team also recommended that teams assess the need for a central line with the ques-tion“Do we need the line today?”and a second question,“If a line was not in place today, would one be placed?” This phrasing reframes the real ne-cessity for a central line.

The addition of these elements to our maintenance bundle accounts for our relatively low maintenance compliance. When we removed these elements, PQCNC CLABSI maintenance compliance at in-tervention end increased from 56% to 72%. It is likely that for neonatal central lines a focus on reliable implementation of neonatal specific bundles that includes

standardization of practices related to line removal offers the greatest opportunity to reduce CLABSIs.22These 2 new elements

required providers to daily consider line necessity in a more standardized fashion. We believe adding these elements to the standard maintenance bundle on the basis of the trend to state positively that

“if a line were not in place today one would be placed” and the significant adoption of our enteral feeding guideline made the bundle a key factor in the re-duction we report in CLABSI rates.

The concern in any successful QI project is sustainability. On the basis of 1 planned quarter of follow-up data, PQCNC CLABSI sustained its gains. We achieved a mean reduction to 1.16 infections per 1000 line days. CLABSI rates in the quarter after PQCNC CLABSI decreased to 0.87 per 1000 line days, and we are also able to report that baseline data obtained for a national CLABSI prevention project in the July quarter of 2011 revealed that our 13 PQCNC CLABSI centers had an aggregate CLABSI rate of 0.67 infections per 1000 line days.

The impact of PQCNC CLABSI on the bur-den of NICU infection in North Carolina

cannot be overstated. In the year after PQCNC CLABSI (July 2010 to June 2011), based on a sustained mean CLABSI rate of 1.16 per 1000 line days and an annual number of line days based on the average of our 12 quarters of observation (41 110), the 13 PCQCNC CLABSI centers avoided 114 CLABSIs. The financial im-pact of nosocomial bloodstream in-fection has been analyzed by Donovan et al.23Most CLABSIs observed in PQCNC

CLABSI were in VLBW infants, but modi-fying the observed 30% mortality rate reported by Donovan et al for VLBW infants in Ohio to 15% for our collabo-rative, which included all infants, and applying their cost differential of $16 800 for hospital charges in infected infants, we can estimate that PQCNC CLABSI saved 17 lives and $1 915 2000 in hospital charges.

There are several possible limitations to our report. First, our baseline NHSN data extend back only to January 2008. As a result, 7 points establish our stable baseline infection rate. Although a longer baseline period would offer more con-vincing evidence of a stable baseline, our baseline extended over 21 months and included 113 000 line days in 13 NICUs. We are confident that this baseline is representative given the dramatic change over the course of the initiative. Second, this initiative was undertaken without the opportunity to record base-line activity for adherence to bundles. Although October 2009 serves as our baseline for process indicators, this ini-tiative was intensively developed with expert team members from all centers over the preceding 3 months. Some fa-cilities began early adoption of bundle elements, but it is impossible to assess the extent of early adoption in the July through September development period. Third, all bundle and NHSN data were self-reported with no requirement to validate NHSN or process data accuracy. The potential inaccuracies of NHSN data have been described by others.24

FIGURE 3

PQCNC CLABSI rates based on aggregate NHSN reporting expressed as CLABSIs per 1000 line days per quarter. For each quarter, total line days are reported in parentheses. CL, center line.

reporting facility in their state collabo-rative, but PQCNC CLABSI did not have this capability. Finally, of great interest in NICUs are not only CLABSI rates but the impact of CLABSI prevention efforts on non-CLABSI and overall nosocomial in-fection rates. Although we did not mea-sure these directly in PQCNC CLABSI, we do have Vermont Oxford Network PQCNC data, which reveal a 28% decrease in all nosocomial infection rates for VLBW infants at participating centers from 2009 to 2010.

CONCLUSIONS

PQCNC CLABSI demonstrated that, al-though an ambitious timeline was used, it was possible to execute a successful NICU collaborative with a well-designed action plan, committed hospital lead-ership, structured team support, and an effective data system that supported the largest repository of reporting on central line maintenance care. Keys to PQCNC CLABSI success were the en-gagement of multiple providers on broad-based teams in NICUs, active partnership with families, the inclusion of bundle elements that focused the teams on line maintenance care and reduction in catheter dwell time, and a data-reporting system that required multiple NICU providers daily to review line maintenance care. Although we did not achieve a 75% CLABSI reduction rate, our 71% reduction rate is the

As CLABSI rates decrease due to ongo-ing QI efforts, large collaboratives will be needed to identify methods to fur-ther reduce, and possibly eliminate, increasingly rare NICU CLABSIs. The success of PQCNC CLABSI should inspire investigators to intensify efforts to as-sess the individual elements and role of maintenance checklists in reducing CLABSIs, evaluate the impact of CLABSI reduction on nosocomial infection rates, further define the impact of dwell times on CLABSI rates for different line types, measure the impact of NICU culture on CLABSI reduction, enhance methods to improve the development of truly multi-disciplinary hospital QI teams, and strengthen partnerships with parents. Our reported experience with checklists, and our appreciation for the manpower requirements of secondary data entry, should further be a call to all interested in QI to pursue methods that support bed-side data entry and real-time clinical decision support tools applicable within and across health care systems to sup-port health care improvements. Such advances will allow us to make QI efforts aimed at reducing the burden of NICU infection an opportunity to not only prevent infection in future infants but to avoid infections in the infants we care for today.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PQCNC participating hospitals and key perinatal QI team members included

Felisa Perkins-Lewis, and Sheri Carroll; Brenner Children’s Hospital: Tammy Haithcox, Cherrie Welch, and Patricia Harold; Caromont Regional Medical Cen-ter: Laura Magennis, Millie Home, and Kevin Coppage; Catawba Valley Medical Center: Andrea Flynn, Trish Beckman, Rachel Wetz, Lori McNeely, Michelle Mace, and David Berry; Cone Health Women’s Hospital: Tina Hunsucker, Helen Mabe, Nancy Micca, Lisa Maxson, Amanda French, and John Wimmer; Duke Children’s Hospital and Health Center: Martha Schaub-Bordeaux, Nicole Cas-tle, Mary Laura Smithwick, and Mike Cotten; First Health of the Carolinas Moore Regional Hospital: Nicholas Lynn, Maryellen Lane, Lisa Valverdes, Jayne Lee, Maggie Craft, and Nicholas Lynn; Jeff Gordon’s Children’s Hospital at Carolinas Medical Center North-east: Christie Baggarly, Brandi Newman, Charlene Head, Tinky Whittington, and Robert Silver; Levine Children’s Hospital: Callie Dobbins, Pamela Spivey, Gail Har-ris, Lori Erwin, Julie Barfield, and Andrew Hermann; North Carolina Children’s Hos-pital: Carol Manenti, Joebeth Bongares-Brown, Linda Denton, Joanne Kilb, Jean-Paul Dame, Karen Wood, and Wayne Price; Novant Health Forsyth Medical Cen-ter: Ann Smith, David Lambert, Jane Aghai, and Robert Dillard; Vidant Children’s Hos-pital: Rhonda Creech, Sharon Buchwald, and Jim Cummings; and WakeMed Children’s: Heidi Gallart, Susan Gutier-rez, and Tom Young.

REFERENCES

1. Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An intervention to decrease

catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU.N

Engl J Med. 2006;355(26):2725–2732 2. Weber DJ, Brown VM, Sickbert-Bennett EE,

Rutala WA. Sustained and prolonged

re-duction in central line-associated blood-stream infections as a result of multiple

interventions. Infect Control Hosp

Epi-demiol. 2010;31(8):875–877

3. Marsteller JA, Sexton JB, Hsu YJ, et al. A multicenter, phased, cluster-randomized

controlled trial to reduce central

line-associated bloodstream infections in in-tensive care units.Crit Care Med. 2012;40

(11):2933–2939

4. Wheeler DS, Giaccone MJ, Hutchinson N, et al. A hospital-wide quality-improvement

collabo-rative to reduce catheter-associated

blood-stream infections. Pediatrics. 2011;128(4).

Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/ full/128/4/e995

5. Sengupta A, Lehmann C, Diener-West M, Perl TM, Milstone AM. Catheter duration

and risk of CLA-BSI in neonates with PICCs. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):648–653

6. Advani S, Reich NG, Sengupta A, Gosey L,

Milstone AM. Central line-associated blood-stream infection in hospitalized children

catheters: extending risk analyses outside the intensive care unit.Clin Infect Dis. 2011; 52(9):1108–1115

7. Raad I, Costerton W, Sabharwal U, Sacilowski M, Anaissie E, Bodey GP. Ultrastructural analysis of indwelling vascular catheters: a quantitative relationship between luminal colonization and duration of placement. J Infect Dis. 1993;168(2):400–407

8. Miller MR, Griswold M, Harris JM II, et al. Decreasing PICU catheter-associated bloodstream infections: NACHRI’s quality transformation efforts.Pediatrics. 2010;125 (2):206–213

9. Sharpe E, Pettit J, Ellsbury DL. A national survey of neonatal peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) practices. Adv Neonatal Care. 2013;13(1):55–74

10. Wirtschafter DD, Pettit J, Kurtin P, et al. A statewide quality improvement collaborative to reduce neonatal central line-associated blood stream infections. J Perinatol. 2010; 30(3):170–181

11. Wirtschafter DD, Powers RJ, Pettit JS, et al. Nosocomial infection reduction in VLBW infants with a statewide quality-improvement model.Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):419–426 12. Kaplan HC, Lannon C, Walsh MC, Donovan EF;

Ohio Perinatal Quality Collaborative. Ohio statewide quality-improvement collaborative

to reduce late-onset sepsis in preterm infants.Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):427–435 13. Schulman J, Stricof R, Stevens TP, et al; New

York State Regional Perinatal Care Centers. Statewide NICU central-line-associated bloodstream infection rates decline after bundles and checklists. Pediatrics. 2011; 127(3):436–444

14. Miller MR, Niedner MF, Huskins WC, et al; National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Central Line-Associated Blood-stream Infection Quality Transformation Teams. Reducing PICU central line-associated bloodstream infections: 3-year results. Pedi-atrics. 2011;128(5). Available at: www.pediat-rics.org/cgi/content/full/128/5/e1077

15. Li S, Bizzarro MJ. Prevention of central line associated bloodstream infections in critical care units.Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011;23(1):85–90 16. The California Perinatal Quality Care Col-laborative. The CPQCC/CCS Healthcare As-sociated Infection (HAI) Collaborative. Available at: http://bit.ly/128GZv9. Accessed August 5, 2013

17. The Ohio Perinatal Quality Collaborative. Neonatology Decreasing Bloodstream Infections Project. Available at: https:// opqc.net/node/144. Accessed August 5, 2013

18. O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Dellinger EP, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Pre-vention. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51(RR-10):1–29 19. Gerald JL, Moen R, Nolan KM, Nolan TW,

Norman CL, Provost LP. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009:23–25 20. Benneyan JC, Lloyd RC, Plsek PE. Statistical

process control as a tool for research and healthcare improvement. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(6):458–464

21. Gabby. The Perinatal Quality Collaborative of North Carolina (PQCNC). Available at: www.pqcnc.org/?q=node/12878. Accessed August 5, 2013

22. Richter JM, Brilli RJ. It’s all about dwell time—reduce it and infection rates de-crease?Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):820–821 23. Donovan EF, Sparling K, Lake MR, et al; Ohio

Perinatal Quality Collaborative. The in-vestment case for preventing NICU-associated infections.Am J Perinatol. 2013;30(3):179–184 24. Thompson DL, Makvandi M, Baumbach J. Validation of central line-associated blood-stream infection data in a voluntary reporting state: New Mexico. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(2):122–125

(Continued fromfirst page)

She cleaned the enormous data set, identified inconsistencies, was responsible for regularly contacting facilities to retrieve missing data and to assist facilities with questions regarding data submission, and reviewed and contributed to revisions of thefinal manuscript. Ms Metzguer was the quality improvement advisor for the project. She assisted in the development of the action plan and helped facilitate the PQCNC CLABSI Expert Team. She assisted in the development of teams at all hospitals, facilitated LSs and reviewed thefinal manuscript. Dr Testoni conducted statistical analysis on all PQCNC CLABSI data. She reviewed the manuscript, made suggestions regarding data presentation in thefinal manuscript, and approved thefinal submission. Dr Smith reviewed the manuscript, the complete PQCNC CLABSI data set, and made key suggestions regarding data analysis. He made suggestions for revisions to manuscript drafts that were incorporated into thefinal manuscript. Dr McCaffrey championed the selection of CLABSI as thisfirst PQCNC project. He oversaw the development of the project outline and facilitated the formation of the expert team. He led recruitment of teams statewide, led 3 monthly webinars, presented at all LSs, and conducted the initial data analysis, which was refined with the critical assistance of Mr Provost and Drs Testaroni and Smith. He was the primary draft author with support from all of the above-mentioned authors.

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2013-2000 doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2000

Accepted for publication Aug 21, 2013

Address correspondence to Martin J. McCaffrey, MD, CAPT USN (Ret), Division of Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, CB 7596, 4th Floor, UNC Hospitals, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7596. E-mail: martin_mccaffrey@med.unc.edu

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275). Copyright © 2013 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE:The authors have indicated they have nofinancial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING:Funding for PQCNC CLABSI was provided by a Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services Neonatal Outcomes Improvement Project Transformation grant administered by the North Carolina Division of Medical Assistance (1UOCMS030303-NC MTG grant); an Investments for the Future (IFF) grant administered by the Dean of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC; and legislative funds directed by the North Carolina General Assembly to the Perinatal Quality Collaborative of North Carolina.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST:The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2013-2000 originally published online November 18, 2013;

2013;132;e1664

Pediatrics

Karen Metzguer, Brian Smith, Daniela Testoni and Martin J. McCaffrey

David Fisher, Keith M. Cochran, Lloyd P. Provost, Jacquelyn Patterson, Tara Bristol,

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/132/6/e1664

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/132/6/e1664#BIBL

This article cites 20 articles, 9 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

ent_safety:public_education_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/patient_education:pati Patient Education/Patient Safety/Public Education

b

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/hospital_medicine_su Hospital Medicine

_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/hematology:oncology Hematology/Oncology

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2013-2000 originally published online November 18, 2013;

2013;132;e1664

Pediatrics

Karen Metzguer, Brian Smith, Daniela Testoni and Martin J. McCaffrey

David Fisher, Keith M. Cochran, Lloyd P. Provost, Jacquelyn Patterson, Tara Bristol,

NICUs

Associated Bloodstream Infections in North Carolina

−

Reducing Central Line

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/132/6/e1664

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.