COMMENTARY

Weighing the Risks of Consumer-Driven Health Plans

for Families

Margaret A. McManus, MHSa,b, Stephen Berman, MDc,d, Thomas McInerny, MDe,f, Suk-fong Tang, PhDg

aConsultant, American Academy of Pediatrics, Elk Grove Village, Illinois;bMaternal and Child Health Policy Research Center, Washington, DC;cChair, American Academy

of Pediatrics Private Sector Advocacy Advisory Committee, Elk Grove Village, Illinois;dDepartment of Pediatrics, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver,

Colorado;eChair, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Health Financing, Elk Grove Village, Illinois;fDepartment of Pediatrics, University of Rochester

Medical Center, Rochester, New York;gDepartment of Practice and Research, American Academy of Pediatrics, Elk Grove Village, Illinois

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

O

NCE a year most employed families must choose which health insurance benefit plan best meets their health and financial needs. Most often these deci-sions are made on the basis of premium price, antici-pated health care requirements, past experience, and network physicians and hospitals. In the last couple of years, in response to persistent double-digit premium inflation, new insurance products and spending ac-counts have been added to the mix of choices that are offered to families. The most popular of the new “con-sumer-driven” health options are high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) coupled with health savings accounts (HSAs). To many families, consumer-driven health plans (CDHPs) are attractive because premiums in HDHPs are typically lower than in preferred provider organization (PPO) or health maintenance organization (HMO) plans and money in tax-free HSAs can be accumulated over time. To many employers, they are attractive because more financial decision-making and risk can be shared with employees.Here we weigh the coverage, cost, quality, and prac-tice management trade-offs that may result when fami-lies select CDHPs. Using a case study of a real Midwest company’s health insurance offering and a hypothetical family with 2 children, it is possible to understand both the lure and trap of these products, especially for low-income families and previously uninsured families, as well as for healthy families. Becoming informed about HDHPs and HSAs (and other CDHP options) is essential for families and pediatricians. Although in 2004 only 10% of employers offered an HDHP, a much higher proportion of employers (27%) are considering offering such coverage by 2006.1At this point, most employers

are offering HDHPs as one of several choices, not as the only option. Unfortunately, there are no reliable na-tional estimates of the number of adults and children enrolled in HDHPs with HSAs.

According to the Internal Revenue Code, an HDHP is an insurance plan, typically a PPO plan, that has a de-ductible of at least $2000 per family and $1000 per individual along with annual out-of-pocket expenses (including deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance) that cannot exceed $10 000 per family and $5000 per individual. Except for preventive care, an HDHP cannot reimburse covered benefits until the deductible for that year is met. This exception, referred to as a “safe harbor,” was created for preventive care services such that an HDHP may (but not must) pay for preventive care ben-efits without having exceeded the deductible. Preventive care is defined to include, but is not limited to, routine well-child care, immunizations, screening for pediatric conditions, vision- and hearing-disorders screening, and metabolic, nutritional, and endocrine conditions screen-ing, mental health conditions and substance abuse screening, and infectious disease screening. Generally

Abbreviations:HDHP, high-deductible health plan; HSA, health savings account; CDHP, consumer-driven health plan; PPO, preferred provider organization; HMO, health maintenance organization

Opinions expressed in these commentaries are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the American Academy of Pediatrics or its Committees.

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2005-1409

doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1409

Accepted for publication Sep 19, 2005

speaking, HDHPs are designed to cover catastrophic ex-penses and, as such, tend to offer less comprehensive benefits and have more stringent cost-sharing require-ments than conventional health insurance products.

HSAs, which became available on January 1, 2004, with the Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act, are tax-free investment accounts for qualified medical expenses2 and are available only to families and individuals in HDHPs. Annual contributions (deducted from the employee’s paycheck) can be made of up to $5150 per family and $2600 per individual and will increase with inflation in future years. Families and individuals own and control the money in their HSAs, although employers may contribute, and unused funds are automatically rolled over year after year.

CASE STUDY OF COMPANY “HEALTHY” AND ITS CDHP Company Healthy, an actual company renamed for the purpose of this article, offers its Midwest employees the choice of a conventional PPO plan and an HDHP with an HSA. Table 1 compares the coverage and costs under these 2 plans. (Note that prescription drugs have to be purchased through a separate rider and, as such, are not factored into the comparison.)

Table 1 shows the advantages of the “PPO Xtra” HDHP product with its no-cost premium and $400 em-ployer HSA contribution and the advantages of the PPO product with its lack of deductible, more generous an-nual out-of-pocket maximum protection, broader bene-fit coverage, and lower cost sharing. Despite the distinct cost and coverage advantages and disadvantages of each type of plan, research reveals that families often make their insurance-purchase decision primarily on the basis of premium price, and in this case, Company Healthy clearly priced its product to attract employees.3Families often do not factor into their insurance decisions the implications that a significant deductible, coinsurance rather than copayments, and a high out-of-pocket max-imum will have on their financial ability to access cov-ered benefits.

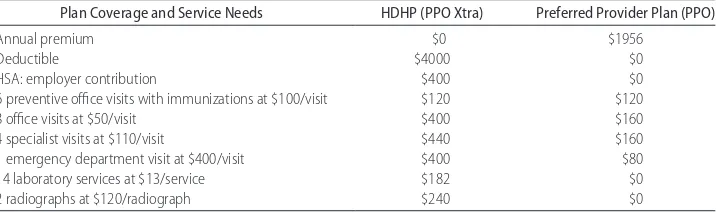

So how might a hypothetical family of 4, with 2 children (aged 1 and 4 years, with the older child having asthma) fare under each of these plans? Table 2 shows the difference. Although this is a typical family, the impact of an HDHP may be greater when the family has a child(ren) with special needs whose care is likely to exceed the maximum out-of-pocket expense. In addi-tion to this difference, families with special-needs chil-dren need to consider what benefits are covered as well as their scope and duration. For example, limitations on home health care services and ancillary therapy services may be a more important consideration than the differ-ence in the out-of-pocket maximum.

The total estimated medical expenditures for this hy-pothetical family of 4 (taking into account premium and visit fees, deductibles, HSA amounts, and cost-sharing requirements) is $1382 in the HDHP (PPO Xtra) and $2486 in the PPO. The main factor accounting for this price difference is the premium, which is fully paid for by the employer in the HDHP. Out-of-pocket service costs in the form of copayments and coinsurance, however, are significantly lower in the PPO. Clearly, the healthier the family, the more financial advantages accrue under this HDHP compared with the PPO. Should this family have a child (or a parent) with more significant chronic conditions or persistent acute conditions, the differential between these 2 plans would be more significant, likely favoring the PPO. The following discussion on coverage, cost, quality, and practice administration associated with HDHPs attempts to highlight the potential risks associ-ated with these new products.

COVERAGE RISKS

Coverage in HDHPs is usually less comprehensive than PPO or HMO coverage, which is why they are often referred to as “catastrophic plans.” Take the example of Company Healthy’s PPO Xtra: coverage for prescription drugs is not included and mental health visits are cov-ered but limited. With respect to physician and hospital services, benefits are similar but not cost sharing; pro-vider networks may be different, as well. The remaining

TABLE 1 Comparison of Coverage and Costs in Company Healthy’s HDHP and PPO Benefit Choices

Features HDHP (PPO Xtra) Preferred Provider Health Plan (PPO)

Premium None $1956

HSA: employer contribution $400 None

Deductible (family) $4000 None

Annual out-of-pocket maximum $8000 $5000

Preventive care $20 copay $20 copay

Office visit 20% after deductible $20

Specialist visit 20% after deductible $40

Hospitalization 20% after deductible 20%

Emergency department visit 20% after deductible 20%

benefits are similar, but cost sharing differs substantially. Coverage of preventive care and immunization benefits may be more difficult to assess because HDHP benefit contracts often provide limited information about the periodicity and content of covered well-child services. They may, for instance, simply reference coverage of preventive care that adheres to the US Preventive Ser-vices Task Force. This may sound impressive to families, but these standards are not consistent in content or periodicity with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommended preventive care standards.3Another cov-erage concern with preventive care and immunizations under HDHPs is that employers are not required to forego deductible requirements, although many seem to be electing this option.

It is important to note that in the 19 states with mandates for preventive care (referred to as CHIRP man-dates [Child Health Improvement Reform Plan laws]), HDHPs are required to cover preventive care but not necessarily before the deductible is met (depending on state law). Exemptions from these state CHIRP mandates include self-funded firms and insurers in states that al-low the sale of “bare-bones” plans. Since 1999, at least 12 states have passed legislation allowing insurers to sell bare-bones policies that do not adhere to mandated state benefit requirements, and since 2004 several more states have introduced similar legislation.4Half of the 12 states, however, allow only for small businesses or those in the individual market to purchase such policies. Other states allow sale of bare-bones policies to a larger market on a demonstration basis.

FINANCIAL RISKS

Families insured through HDHPs undoubtedly will face greater exposure to financial risk, with higher deduct-ibles and annual out-of-pocket maximums and also higher cost-sharing requirements for certain services. Imagine a family earning $35 000 and expending $4000 or more of their own money (either from their HSA or directly out of pocket) each year before insurance reim-burses them for any care except preventive care.

Predict-ably, lower-income families will forego all but significant acute or emergent care, which in the long run may lead to higher costs. In fact, national data reveal that⬍5% of families with incomes ⬍200% of the federal poverty level expend more than $4000 for medical care (S.f.T., unpublished data [special analysis of pooled 1996 –2002 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey data conducted for this article, American Academy of Pediatrics], September 15, 2005). Another volatile group is families whose chil-dren have special health care needs, who can expect to face higher out-of-pocket costs in HDHPs than in con-ventional insurance products and have less catastrophic protection in the form of annual and lifetime maxi-mums.

Financial benefits of HDHPs can accrue to healthy families who use health services sparingly. In fact, there is some literature suggesting that individuals with low annual health care expenditures will also have lower expenditures under HDHPs than under managed care plans.5 If families only use preventive care for their children, which is likely to be exempt from deductible requirements, and consume very few other services, they will likely be able to save money in their HSAs. Of course, should these same families encounter a serious acute or ongoing chronic condition, the financial advan-tages of HDHPs will disappear.

Families also may find that per-service health care charges are higher when the insurance “middleman” is removed and they are paying providers directly, which is what they will be doing until their high deductibles are met. That is, families will not be able to negotiate or obtain discounted charges from providers that are cur-rently available through most conventional health plans. In addition, families will have to keep careful records of their HSA expenditures, in some cases through check-books and credit cards and in other cases through a “shoebox.” Another significant financial risk is the im-pact of healthier families choosing HDHPs, leaving con-ventional HMO and PPO plans with a sicker population and higher premium prices.

TABLE 2 Comparison of the Hypothetical Family’s Out-of-Pocket Expenses Under Company Healthy’s HDHP and PPO Benefit Plans

Plan Coverage and Service Needs HDHP (PPO Xtra) Preferred Provider Plan (PPO)

Annual premium $0 $1956

Deductible $4000 $0

HSA: employer contribution $400 $0

6 preventive office visits with immunizations at $100/visit $120 $120

8 office visits at $50/visit $400 $160

4 specialist visits at $110/visit $440 $160

1 emergency department visit at $400/visit $400 $80

14 laboratory services at $13/service $182 $0

QUALITY RISKS

Probably the most significant risks under HDHPs are quality risks. Families, especially those with low in-comes, who have high deductibles are likely to delay or avoid seeking care, including preventive care. Previous research has shown that the greater the level of cost sharing, the lower the level of service utilization.6–8 In addition, continuity of care and compliance with recom-mended referrals to specialists, treatments, laboratory tests, and radiographs may be affected adversely. In addition, in-network provider panels in HDHPs that include pediat-ric subspecialists and hospitals specializing in the care of children may be more expensive than those that include primarily adult specialists and community hospitals.

Families that are concerned about future medical ex-penses may seek to preserve money in their HSAs. For example, they may decide not to immunize their chil-dren because the perceived risks of contracting infec-tious diseases are low. Alternatively, they may use their HSAs for elective services not otherwise covered in con-ventional health insurance plans or turn to lower-cost alternative treatment options (eg, over-the-counter drugs versus prescription drugs). Clearly, families will be called on to make many more decisions, relying on Internet-based support systems and other online infor-mation to guide them and also turning to the pediatri-cians and other physipediatri-cians for advice and guidance on the cost/quality trade-offs.

PRACTICE-ADMINISTRATION RISKS

Moving from the perspective of families to those of physicians, a growing number of pediatricians are re-porting that their patients have HDHPs and HSAs and these families expect to manage their payments differ-ently than under conventional health plans. Physicians in some participating HDHPs have been notified not to collect copays at the time of service but rather to wait until an explanation of benefits is received before billing patients for deductible and coinsurance amounts. This obviously adds more administrative and collections bur-den to the practice, significantly retards cash flow, and creates an unfortunate tension between the family and the practice. Also, credit or debit cards or HSA checking accounts are being used to pay for care, and practices may incur financial risk depending on the balance of available HSA funds. Other practice-administration issues relate to how seamless reimbursement will be when families have exceeded their deductible and insurance finally “kicks in.” Although health care providers have more freedom to price and market their services differently in HDHPs than in conventional insurance plans, with this indepen-dence comes a substantial responsibility to inform fam-ilies about service charges, the value of specific services,

and other customer service activities. Legal and ethical concerns may be raised about tiered pricing in which individuals pay higher prices than do the health plans. It is also likely that there may be an increased demand for telephone and e-mail assistance, because families, pre-dictably, are going to be more cautious about making in-person visits.

CONCLUSIONS

Although CDHPs may represent an important insurance option for single adults and high-income families, they pose serious potential risks for many, if not most, fami-lies, especially those whose children have special needs. We have outlined some of the most obvious coverage, financial, quality, and practice-administration risks. It is clear that pediatricians and other health care providers will need to become more aware of the mix of HDHPs (with their varied benefit designs, different cost-sharing requirements, and tiered provider networks) and at-tempt to work with families each year when insurance decisions are made.

There are countless considerations that families will need to take into account. For example, what is the gap between their HSA and their HDHP? Will spending on preventive care be counted against the HSA, and will the full cost of preventive care be covered through their HDHP? What if unanticipated health problems develop; will needed services be covered? What is the differential between coinsurance and copayments? What pediatric providers are in the network, what providers are out of the network, and what are the cost differentials between the 2? What are the maximum out-of-pocket costs that families are responsible for in 1 year, and what is the maximum lifetime benefit? Will the plan cover all ser-vices that doctors say are medically necessary? These are just a few of the most obvious questions that should be considered when comparing HDHPs and conventional health insurance plans.

better than no coverage at all, CDHPs, as they are cur-rently designed, represent a serious departure from the basic tenets of health insurance, namely, shared risk, comprehensive coverage, and financial protection.

REFERENCES

1. The Kaiser Family Foundation and the Health Research and Educational Trust.Employer Health Benefits: 2004 Annual Survey. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; and Chicago, IL: Health Research and Educational Trust; 2004

2. Internal Revenue Service. Publication 502 (2005), medical and dental expenses. Available at: www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p502. pdf. Accessed February 27, 2006

3. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Practice and

Ambulatory Medicine. Recommendations for preventive pedi-atric health care.Pediatrics.1995;96:373–374

4. Walter D.State “Bare Bones” Health Insurance Policy Legislation.Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2004 5. Buchmueller TC, Feldstein PJ. Consumer’s sensitivity to health

plan premiums: evidence from a natural experiment in Califor-nia.Health Aff (Millwood).1996;15:143–151

6. McNeill D. Do consumer-directed health benefits favor the young and healthy?Health Aff (Millwood).2004;23(1):186 –193 7. Lurie N, Manning WG, Peterson C, Goldberg GA, Phelps CA, Lillard L. Preventive care: do we practice what we preach?Am J Public Health.1987;77:801– 804

8. Newhouse JP, Manning WG, Morris CN, et al. Some interim results from a controlled trial of cost sharing in health insurance. N Engl J Med.1981;305:1501–1507

CORD BLOOD LAW SIGNED

“An inventory of 150,000 high-quality umbilical cord blood units will be created following President Bush’s signing of the Stem Cell Therapeutic & Research Act of 2005 (HR 2520) on December 20. The new law provides $79 million in federal funding to increase the number of cord blood units. The law also reauthorizes the existing national registry for marrow donors, said the National Marrow Donor Program. According to a statement from the New York Blood Center (NYBC), which led a 3-year campaign for the legislation, cord blood provides a source for blood stem cells equivalent or superior to bone marrow. Unlike bone marrow, cord blood does not have to be a perfect match to a patient’s tissue type, making it easier to find matches for patients with various blood diseases, as well as certain immune and metabolic dis-eases. Another advantage to cord blood is that it is banked, fully tested, and ready to go whenever it is needed, the NYBC said. It is estimated that the national cord blood inventory will provide suitable matches for up to 90% of patients, regardless of ethnic background. This is equivalent to a marrow donor registry of several million volunteers.”

Mitka M.JAMA.2006;295:617

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2005-1409

2006;117;1420

Pediatrics

Margaret A. McManus, Stephen Berman, Thomas McInerny and Suk-fong Tang

Weighing the Risks of Consumer-Driven Health Plans for Families

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/117/4/1420 including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/117/4/1420#BIBL This article cites 4 articles, 2 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

_management_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/administration:practice

Administration/Practice Management

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2005-1409

2006;117;1420

Pediatrics

Margaret A. McManus, Stephen Berman, Thomas McInerny and Suk-fong Tang

Weighing the Risks of Consumer-Driven Health Plans for Families

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/117/4/1420

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.