Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) was identified more than 100 years ago.1 It is a degenerative disease of the brain and the most common cause of dementia in older people, accounting for 60% to 80% of cases of late-life cognitive dysfunction.1,2,3 There is a common misconception that dementia is merely a natural consequence of aging. Yet, dementia is a condition that impairs the cognitive brain functions of memory, language, perception and thought, significantly interfering with the ability to maintain activities of daily living.4,5,6 The risk of developing dementia increases significantly with age; however, it is not a predictable consequence of aging.7

Alzheimer’s disease/dementia is contributing to the global non-communicable disease burden, and it is a leading source of morbidity and mortality in the aging population.4 According to the latest statistics, Alzheimer’s disease/dementia is amongst the top 50 causes of death in South Africa, ranking 27th with an age adjusted death rate of 7.67 per 100 000 and accounting for 2 664 annual deaths (0.48%). South Africa is ranked 31st in the world in terms of Alzheimer’s as the cause of death.8

Dementia, including AD, is considered one of the major health challenges of current times and a global public health priority.4,9 It affects individuals, families and communities and is a growing cause of disability. Often dementia is hidden, misunderstood and underreported.4,9

Dementia has a major negative effect on people’s functioning, independence, and the need for care. This in turn is placing a heavy burden on families, communities and society, with the cost of care often paid for out-of-pocket. The personal, social and economic consequences of dementia are enormous. Dementia leads to

increased care costs for governments, communities, families and individuals, and to losses in productivity for economies. The cost of care for dementia, estimated at US$ 604 billion per year in 2010, is growing at a faster rate than the prevalence of the disease.4 In 2015 the cost of care was estimated to be US$ 21.6 billion in the African region, which was one of the greatest increases observed since 2010.10

Prevalence and incidence

Worldwide, the overall burden of AD is substantial with an increasing prevalence in the aging population.2,11,12,13 Globally, an estimated 47.5 million people are living with dementia, with 62% of the disease burden in low and middle-income countries, where access to social protection, services, support and care are very limited.9 In future, the number of dementia cases is expected to nearly double every 20 years with the increasing aging population.4,6

In 2016, an estimated 5.4 million people of all ages in the United States were living with AD. This figure includes an estimated 5.2 million people ≥ 65 years and 200 000 people < 65 years, who have younger-onset Alzheimer’s.14 According to the latest evidence from the ongoing Framingham Heart Study in Massachusetts, with more than 5 200 participants, cases of Alzheimer’s are still increasing at an alarming rate, however the rate of increase seems to be declining.15

The incidence of dementia is age-dependent, varies across countries and in general doubles every 10 years after age 60 years.6,12 In Africa, an estimated 818 106 people are developing dementia each year, currently affecting more than 4 million people. This figure is expected to be more than 7 million by 2013 and double to 14 million by 2050. The ageing population

Overview of Alzheimer’s disease and its

management

Johanna C Meyer, Pamela Harirari, Natalie SchellackDepartment of Pharmacy, Faculty of Health Sciences, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University

Correspondence to: Hannelie Meyer, e-mail: hannelie.meyer@smu.ac.za

Keywords: Alzheimer’s, dementia, risks, prevention, care, pharmacotherapy, non-pharmacological

Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease is a degenerative disease of the brain, the most common cause of dementia in the geriatric population, and a major cause of death. Alzheimer’s disease places a heavy burden on families, communities and society, in terms of care and costs. This is compounded by the fact that populations across the world are having a longer life expectancy. An overview of Alzheimer’s as a disease state and its pharmacological and non-pharmacological management is provided in the paper. Caring for the person diagnosed with Alzheimer’s may be taxing and thus caring for the carer is also described.

is considered to be a major contributing factor to the increased prevalence.10

The incidence and prevalence of AD or dementia is not associated with a particular gender. Although in terms of numbers, particularly over the age of 85 years, more females than males have the disease. This is explained by the better life expectancy amongst women.8,16

There is a paucity of published epidemiological data on the prevalence of dementia and AD in South Africa and in other low- and middle-income countries.17,18 According to estimates in the World Alzheimer Report 2015 there were almost 186 000 people living with dementia in South Africa, of whom nearly 75% were women. This number is expected to rise to nearly 275 000 by 2030.6 A pilot study conducted in a rural black community of 2000 households in Bloemfontein, South Africa, showed a prevalence of 6.4% for dementia diagnosed by DSM-IV criteria.18

Disorders associated with neurodegeneration such as traumatic brain injury, alcohol dependence and HIV infection are increasingly affecting adults in South Africa. HIV-associated dementia (HAD) is prevalent in 15–30% of untreated adults with late-stage disease. Older adults, who already have an increased risk of non-AIDS-related dementias, are most likely to have untreated HIV. This might further impact the numbers of people with dementia.17

Risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease

Bearing in mind the projected increase in the number of people who will be affected with AD and dementia within the next 20–30 years, there is an urgent need to identify opportunities for effective prevention to mitigate this.9

Genetic risk factors

Apart from age as the major risk factor for AD, the most clearly established risk factors, although not fully understood yet, are a family history of dementia, rare dominantly-inherited mutations in genes that impact amyloid in the brain, and the apolipoprotein E (APOE) epsilon 4 (e4) allele.19 Evidence has shown that family history of dementia as a risk factor for the development of AD varies with the type of family relationship, the age of onset of disease and the race. The risk of developing AD increases with 10-30% if an individual has a first degree relative with dementia. Compared to the general population, where two or more siblings are affected with late-onset AD, the risk of AD increases three-fold.19 With late-onset AD, APOE is the main genetic risk factor involved. Compared to non-carriers, people who are carriers of one or two e4 allele are respectively at a 2- to 3-fold and 8- to 12-fold increased risk of developing AD.19 The strength of the association is further modified by factors such as gender, race and vascular risk factors.19

Acquired risk factors

There are a number of acquired factors that may influence the risk for Alzheimer's disease.15,19,20,21 Risk factors include hypertension,

lipoproteins, cerebrovascular disease, altered glucose metabolism, and brain trauma, of which many appear to be most relevant when present in midlife.19 Hence, a key strategy to reduce the risk, progression and severity of AD would be to manage these factors during midlife.19,20

Published evidence from various studies suggested an association between certain pharmacological classes (e.g. benzodiazepines, anticholinergics, antihistamines, opioids) and cognitive impairment in older adults. The relationship, however, is not fully understood yet. In most cases the effects have been recognised to be temporary and reversible, while in other studies, especially in the case of long-term exposure, cognitive effects may not be reversible in some patients.19,22

Environmental risk factors

Apart from apolipoprotein E (APOE) epsilon 4 (e4), genetic studies showed limited predictive effects on Alzheimer’s onset. This sparked renewed interest in directing resources towards investigating environmental and toxic exposures as potential risk factors for AD.23 Potential environmental risk factors being investigated include second hand smoke, air pollution and pesticides.19

Protective factors and prevention

While treatments to prevent or cure AD are urgently needed, evidence has shown that steps can be taken to delay the onset of AD.15 Recent epidemiological data from the Framingham Heart Study in the United States, suggest that the onset of dementia might be prevented, or at least delayed, by higher levels of education and heart-healthy lifestyle measures.15 A decline in the risk for developing dementia was observed amongst those who had at least a high-school education.15 Higher levels of education together with intellectual or cognitive stimulation assist in building a robust connection of brain cells or cognitive reserve.5 In the case of degeneration of brain cells, there will be sufficient brain cells remaining to keep memory and thinking intact and help to limit the onset of AD. This also explains why previous studies recommend activities such as crossword puzzles, reading books, learning a new language or playing a musical instrument, which may help to curb Alzheimer’s in old age.15 Evidently, higher levels of education alongside cognitive activity produce a cognitive reserve that decreases the impact of neurodegeneration on cognitive function.5

Three components of lifestyle, i.e., social, mental, and physical activity, are evidently inversely associated with the risk for dementia and AD.15,23-25 Although more data and robust studies are needed to confirm this relationship, lifestyle activities play a role in other preventative strategies such as cognitive function and healthy-heart lifestyle.15

yet.4 The Framingham Heart Study also observed risk factors for heart disease like smoking, high blood pressure and obesity. Evidently, the risk of developing dementia was also decreased where cardiovascular factors were better controlled. Regular physical activity is known to improve blood vessel health, including in the brain, and may stimulate levels of nerve growth factors in the brain. Furthermore, regular exercise controls obesity and diabetes, which both are associated with an increased risk for developing AD.15

Pathophysiology

Alzheimer’s disease is a degenerative brain disorder characterised by the destruction of nerve cells and neural connections in the cerebral cortex of the brain.26 It is also characterised by aggregation of amyloid β (Aβ) in extracellular senile plaques, and formation of intraneuronal neurofibrillary tangles consisting of hyperphosphorylated tau protein. This results in progressive and irreversible memory deterioration, as well as deterioration of various cognitive functions, leaving the patient dependent on other people and requiring full-time medical care.27

Epidemiological studies have shown AD to be the leading cause of dementia.27 According to Dumanski et al. (2016),28 AD is complex and may have a number of pathways contributing to its pathology. The majority of early-onset AD patients do not illustrate a clear autosomal pattern of inheritance. However, rare autosomal dominant forms of AD exist, predominantly manifesting as early-onset AD.26 Although the pathogenesis of AD remains unclear, all forms of AD appear to have overproduction and/or decreased clearance of amyloid β peptides in common.19 Mutations in three genes – amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin 1 (PSEN1) and presenilin 2 (PSEN2) – were identified to cause AD, even though they are accountable for less than 1% of AD cases.29

Although late-onset AD is regarded as multifactorial, it involves a strong genetic predisposition.26 The genetic component itself is complex and heterogeneous (i.e. more common but less penetrant), because there is no single model that explains the mode of disease transmission, and gene mutations or polymorphisms may interact with each other and with environmental and other non-genetic influences, such as, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease and brain trauma.19,29 The common genetic risk factor associated with late-onset AD is apolipoprotein E (APOE). The genetic predisposition of the non-Mendelian form of AD is quite substantial, even for late-onset AD patients, with a heritability estimate of 60–80%. Family history can be considered as a risk factor for the development of AD.19 The translation of genetic findings into functional mechanisms that are biologically important in disease pathogenesis and treatment design has proven to be difficult as the genetic contribution to AD risk remains poorly understood.26

Prospective clinical and biomarker studies have shown that AD pathology (asymptomatic phase) usually presents decades before clinical symptoms appear.30 Clinical diagnosis of AD focuses on the development of dementia rather than on the underlying

neuropathological changes.31 Usually, early cognitive changes may be subtle or non-existent. This makes it difficult for early diagnosis, and thus requires highly sensitive tests targeting specific brain regions affected in the early disease progression. The data regarding structural brain changes in preclinical AD remain unclear. Cortical thinning or hippocampal atrophy has been associated with brain amyloidosis, in some studies, whereas other studies have found no relationship or have reported increased cortical thickness.30 According to Pegueroles et al. (2016),30 another challenge in diagnosing subjects is the fact that brain structure is highly dynamic and evolves with age, making it difficult to distinguish whether effects on brain structure are age-related or disease-specific.

Evidence from previous studies indicates that cognitive decline can be associated with extensive changes across the brain regions responsible for temporally correlated activity at rest and suppression of activity during task-related behaviours, i.e. posterior cingulate and temporoparietal regions, also known as the default mode network (DMN).31 The dysfunction of the DMN may be used as a neuroimaging marker of cognitive decline in preclinical populations. These subjects may present with lack of verbal fluency and sound reasoning, low processing speed and poor function of episodic memory.31

Clinical features, diagnosis and care

There is a long asymptomatic period between the onset of biochemical changes in the brain and the presentation of clinical symptoms of AD.19 A decline in amyloid β 1-42 in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) has been perceived to precede disease onset by 25 years, whereas cognitive impairment seems to manifest only 5 years prior to clinical diagnosis.19

The most common hallmark of AD is memory impairment.32 Deterioration of other cognitive functions is usually accompanied by, or appears after, memory decline. Development of symptoms occurs gradually. Early symptoms of the disease include visuospatial abnormalities and executive dysfunction. Language deficits and behavioural changes are usually noticeable in the later stages of the disease.32

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), patient history and clinical assessment of patients with dementia indicate significant cognitive impairment in one or more of the following cognitive areas; learning and memory, language, executive function, complex attention, perceptual-motor function and social cognition.25

Declarative episodic memory is usually affected in the early stages of AD, whereas, semantic memory tends to be affected at a later stage.32 Diagnosis is usually conducted by testing memory by asking patients to recall series of words or objects immediately, and then after a 5-10 minute delay. Patients may present with the inability to retain new information.25

Diagnosis is done by interviewing the patient’s family, friends or colleagues. The patient may seem to have become disorganised or demotivated, with loss of insight over time. Spatial ability and orientation may be impaired such that patients get lost in familiar places.25

Alzheimer's disease patients may present with neuropsychiatric symptoms such as, apathy, irritability and social disengagement, especially in the later stages of disease.32 It can be difficult to distinguish between apathy and depression, therefore diagnosis should be thorough to rule out depression. Patients with depression tend to visit a physician on their own and may complain of memory loss, whereas patients with AD are usually brought to physicians by family, friends or colleagues, and are unaware of their memory loss.25

Other signs and symptoms are difficulty to handle complex tasks, inability to cope with unexpected events and sleep disturbances, which manifest in the early stages of AD, whereas seizures and apraxia, which can be assessed by asking the patient to perform ideomotor tasks, usually present in the later stages.25,32 The progression of AD is inevitable; however, the progress of disease can be measured using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).25,32

A detailed clinical assessment can provide an accurate diagnosis of AD, but it lacks sensitivity and specificity.32 It is therefore imperative to carry out a detailed cognitive and general neurologic examination. Other diagnostic modes that can be beneficial in identifying AD are neuropsychological assessments,

MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination

Figure 1: Warning signs and stages of Alzheimer’s disease 1,33

Memory problem NOT caused by alcohol abuse / head injury; worsening over time Language problems i.e. difficulty naming objects, finding right word to use Difficulty in fastening zips and buttons or to dress themselves

Personal hygiene not important; may not want to bath; do not care about image Extreme mood swings; change in mood for no reason e.g. being calm then suddenly

scared or angry and aggressive, within minutes

Impaired judgement; strange behaviour e.g. wearing underclothes over top clothes or taking clothes off in public

Get lost in familiar places such as their own neighbourhood Even recognition of their own family and friends becomes difficult

Recalls memories of childhood at times; cannot remember what happened the same day

WARNING SIGNS FOR ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

MODERATE/MIDDLE STAGE (MMSE 10-17)

Problems are more apparentand disabling

LATE/SEVERE STAGE (MMSE 0-9) People are more disabled and need a great deal of help

Loss of speech Misidentifies or is

unable to recognise familiar people Urine and faecal

incontinence Progresses to total

dependence on caregiver e.g. feeding,

toileting, walking Requires care 24 hours a

day, 7 days a week

Crying, screaming, groaning Needs help with basic

activities of daily living e.g. feeding,

dressing, bathing EARLY/MILD STAGE

(MMSE 18-26) Symptoms might only be

apparent in retrospect

Problems with routine tasks

Inability to manage finances

Changes in personality

Confusion & memory loss Misplacing objects Forgetting names and

recent events Disorientation Denial of memory loss

Anxiety, suspicion, pacing, insomnia, agitation, wandering,

paranoid, delusional

Ac

tiv

itie

s o

f

da

ily

liv

in

g

Co

gn

itio

n

Be

ha

vi

our

Difficulty recognising family and friends Chronic loss of recent

memory of events Severe impairment of

recall for recent events

neuroimaging, biomarkers and genetic testing. The most common disorders considered in the differential diagnosis of AD are other neurodegenerative dementias, and vascular dementia, which is caused by ischaemic or haemorrhagic strokes.32

Stages of Alzheimer’s disease

The progression of AD is divided into three main stages namely the mild (early-stage), moderate (middle-stage), and severe (late-stage) (see Figure 1).1,33 Symptoms of AD can be divided into cognitive symptoms, non-cognitive (behavioural) symptoms and activities of daily living.1 Cognitive symptoms present throughout the illness, while behavioural symptoms and activities of daily living are less predictable and depend on the individual patient.1 Understanding what these stages entail, can assist with the personal treatment plan for the patient.1,33

Caring for a person with Alzheimer’s disease

A critical component of an AD patient’s treatment plan is to ensure the patient and the caregiver/s are involved in the care and related decision-making process. Hence, education on the course of illness, prognosis, available treatments, legal decisions, and quality-of-life issues, upon initial diagnosis, is essential.1 The caregiver should also understand how AD changes people, what are the challenges as a result of these changes and how to cope with the subsequent challenges.

Basic principles of care for the patient with AD1,33

• Help family members, friends and others understand the disease. • Find the optimal level of autonomy and adjust expectations for

patient performance over time. • Changes in communication skills

◦ Consider vision, hearing, or other sensory impairments to adapt.

• Changes in personality and behaviour ◦ Avoid confrontation.

◦ Remain calm, firm, and supportive, if the patient becomes upset.

◦ Keep the person with AD safe: In the home, when going out and when driving.

◦ Reduce choices, keep requests and demands of the patient simple, and avoid complex tasks that lead to frustration. ◦ Identify the symptom and causative factors, and adapt the

caregiving environment to remedy the situation.

◦ Personal discomfort may trigger behaviours: Monitor for pain, hunger, thirst, constipation, full bladder, fatigue, infections, skin irritation, comfortable temperature, fears, and frustrations.

◦ Environmental triggers: Noise, glare, an insecure space, and too much background distraction, including television. • Changes in activities of daily living

◦ Provide everyday care: Activity and exercise, healthy diet, personal hygiene, dressing and grooming.

◦ Adapt daily activities: Daily household chores, going out, music, eating out, travel, spiritual activities, holidays, visitors. ◦ Provide frequent reminders, explanations, and orientation

cues.

◦ Employ guiding, demonstration, and reinforcement.

◦ Maintain a consistent, structured environment with stimulation level appropriate to the individual patient.

◦ Interventions should redirect the patient’s attention rather than be confrontational and should specifically address known triggers. Creating a calm environment and removing stressors and triggers is key.

• Attend to medical problems

◦ Commonly include falls, incontinence, constipation, flu, pneumonia, dehydration.

◦ Bring sudden declines in function and the emergence of new symptoms to professional attention.

• Changes in intimacy and sexuality

◦ Address or adapt to changes in intimacy and sexuality. ◦ Reassure the person of love and safety.

• End-of-life care: Moving the person, prevent hurting themselves, swallowing problems, skin problems, foot care.

• Future planning: Plan ahead in terms of health, legal and financial issues.

Caring for the caregiver

Caregivers must be prepared, and able to, face the challenges that will occur as the patient is progressing through the degenerative stages of the disease.1,33 One of the most important aspects of the AD patient’s care is to ensure that the caregiver is taking care of himself/herself.1,33 A number of actions that the caregiver can take, which could potentially bring some relief, improve his/her quality of life and prevent physical and mental illness, are shown in Figure 2.1,33

Management of Alzheimer’s disease

Treating the symptoms of cognitive impairment and maintaining the patient’s functionality for as long as possible are the primary goal of AD treatment.1 This can assist in preserving the patient’s independence and dignity for a longer period of time, as well as assist and encourage caregivers.1,33 Secondary goals include treating psychiatric and behavioural sequelae.1 Presently, there is no cure for AD, neither evidence of available pharmacological treatment to prolong life, nor halt or reverse the pathophysiological processes of the disease.1

REVIEW

clinical trials and further research are being conducted to find a treatment that targets the gene responsible for AD progression.35 A recent study showed that manipulating an early trafficking protein pathway (COPI) which affects APP – a protein that causes the development of Alzheimer’s, amyloid plaques responsible for memory loss and other symptoms of Alzheimer’s can be decreased significantly. The decrease of COPI resulted in some improvement of memory impairment, showing promise for the development of future Alzheimer’s treatments that will slow the progression of the disease.36,37

Non-pharmacological therapy

Non-pharmacological therapies have become more important over the last number of years, as evidence of the role of certain protective factors against the progression of dementia have become available, e.g. physical activity, life style factors and educational stimuli.15 Since there is no current cure for AD – a degenerative disease that negatively affects the quality of life of the patient as well as of the family or carer – non-pharmacological treatment interventions should be considered.

Non-pharmacological strategies to slow disease progression

In view of the slow onset of AD, early intervention has potential benefits for patients. Research evidence has shown that there are non-pharmacological strategies, which may help slow the progression of AD. However, more research is needed in patients with AD. A summary of these strategies appears in Table I.34

A multi-factorial approach to the non-pharmacological strategies in Table 1 is recommended as no one cause has been identified as exclusively contributing to neurodegeneration.34 Many of these strategies are modifiable life-style factors which can be implemented by patients themselves, with support from their caregivers as well as the multi-disciplinary health care team.34 Evidence in this field of AD management is showing promise, hence further research should be encouraged, especially considering that disease modifying pharmacological treatment is still evasive.34

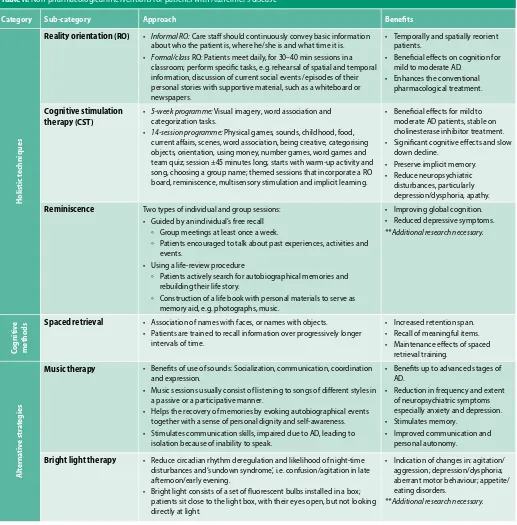

Non-pharmacological interventions to improve cognition and autonomy

Evidence from the literature over the last 10 years identified various interventional tools, which could be used as part of

Table I: Non-pharmacological strategies to slow disease progression34

Strategy Role in slowing disease progression

Blood pressure

• Blood pressure monitoring may have direct benefit on patient’s physical and cognitive health. • Anti-hypertensive medications which manipulate the RAS may be neuroprotective.

Diet

• Adherence to a healthy diet should be advised and supported. • Lower rate of mortality in those who follow a Mediterranean diet.

• Personalised supplementation to address specific dietary deficiencies, e.g. vit D, vit B12 and folate, may be useful. • Sunlight exposure for improving vit D intake.

Exercise

• Almost any physical activity maintained by AD patients may have a role in slowing the progression of cognitive and functional symptoms.

• Exercise helps to protect from consequences of frailty.

Cognitive stimulation therapy (CST)

• Improvements in MMSE. • Improvement in quality of life. • See Table II

Social networks • Maintaining social networks help maintain independence and quality of life.

• Social engagement can reduce agitation - encourage ways to improve social interaction.

Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD)

• Medicines used for behavioural and psychological symptoms have limited effect in AD population.

Non-pharmacological interventions for symptoms of agitation, depression and psychosis need to be investigated further. • Social engagement and steps taken to improve quality of life via diet, physical activity and pain management to protect

from distressing symptoms.

Figure 2: Strategies for caregivers to take care of themselves33

progressing through the degenerative stages of the disease.1,33 One of the most important aspects of the AD patient’s care is to ensure that the caregiver is taking care of himself/herself.1,33 A number of actions that the caregiver can take, which could potentially bring some relief, improve his/her quality of life and prevent physical and mental illness, are shown in Figure 2.1,33

Figure 2: Strategies for caregivers to take care of themselves33

Management of Alzheimer’s disease

Treating the symptoms of cognitive impairment and maintaining the patient’s functionality for as long as possible are the primary goal of AD treatment.1 This can assist in preserving the patient’s independence and dignity for a longer period of time, as well as assist and encourage caregivers.1,33 Secondary goals include treating psychiatric and behavioural sequelae.1 Presently, there is no cure for AD, neither evidence of available pharmacological treatment to prolong life, nor halt or reverse the pathophysiological processes of the disease.1

In the past, a considerable amount of research on developing disease-modifying treatments for AD was conducted.34 Despite many promising preclinical research results, the human clinical trials were unsuccessful. Subsequently, the focus shifted to preventative measures to delay the onset of AD rather than treating the disease. However, it remains imperative to identify strategies that may slow

Get Help with the Caregiving

Build a Support Team Join a Support

Group for AD Caregivers

Take Breaks and Spend Time with

Friends

Get Exercise and Eat Healthy Food

Keep Up with Hobbies and

Interests

Get Counselling to Deal with Stress, Own Feelings and to Plan for Unexpected

Events Consider

Nursing Home or Hospice

Services

Keep Own Health, Legal and Financial Information Up

AD patients’ personalised treatment plan, to improve the cognition and autonomy of daily living and reduce behavioural and psychological symptoms.38 A summary of these non-pharmacological interventions is shown in Table II.38

Non-pharmacological interventions are complementary techniques which should be tailored to the needs of each specific patient considering the individual needs; medical condition; patient’s resilience and adherence to treatment; available health, social services and professional resources; caregiver care commitment; and support.38

Pharmacotherapy (PH)

An important consideration in the treatment of AD patients is the fact that they are older patients and therefore may be taking multiple medicines for other acute or chronic conditions. As the number of medicines increases, the risk for potential adverse drug effects and non-adherence also increases.1 Aside from medicines that temporarily relieve symptoms, there is no curative treatment available for AD.35 This is due to the complex nature of AD pathogenesis.39 Most of the symptomatic treatment attempts to improve or maintain cognition.1

Table II: Non-pharmacological interventions for patients with Alzheimer’s disease38

Category Sub-category Approach Benefits

H

olistic t

echniques

Reality orientation (RO) • Informal RO: Care staff should continuously convey basic information about who the patient is, where he/she is and what time it is. • Formal/class RO: Patients meet daily, for 30–40 min sessions in a

classroom; perform specific tasks, e.g. rehearsal of spatial and temporal information, discussion of current social events /episodes of their personal stories with supportive material, such as a whiteboard or newspapers.

• Temporally and spatially reorient patients.

• Beneficial effects on cognition for mild to moderate AD.

• Enhances the conventional pharmacological treatment.

Cognitive stimulation therapy (CST)

• 5-week programme: Visual imagery, word association and categorization tasks.

• 14-session programme: Physical games, sounds, childhood, food, current affairs, scenes, word association, being creative, categorising objects, orientation, using money, number games, word games and team quiz; session ±45 minutes long; starts with warm-up activity and song, choosing a group name; themed sessions that incorporate a RO board, reminiscence, multisensory stimulation and implicit learning.

• Beneficial effects for mild to moderate AD patients, stable on cholinesterase inhibitor treatment. • Significant cognitive effects and slow

down decline.

• Preserve implicit memory. • Reduce neuropsychiatric

disturbances, particularly depression/dysphoria, apathy.

Reminiscence Two types of individual and group sessions: • Guided by an individual’s free recall

◦ Group meetings at least once a week.

◦ Patients encouraged to talk about past experiences, activities and events.

• Using a life-review procedure

◦ Patients actively search for autobiographical memories and rebuilding their life story.

◦ Construction of a life book with personal materials to serve as memory aid, e.g. photographs, music.

• Improving global cognition. • Reduced depressive symptoms. **Additional research necessary.

Co

gnitiv

e

metho

ds Spaced retrieval • Association of names with faces, or names with objects.• Patients are trained to recall information over progressively longer

intervals of time.

• Increased retention span. • Recall of meaningful items. • Maintenance effects of spaced

retrieval training.

A

lterna

tiv

e str

at

egies

Music therapy • Benefits of use of sounds: Socialization, communication, coordination and expression.

• Music sessions usually consist of listening to songs of different styles in a passive or a participative manner.

• Helps the recovery of memories by evoking autobiographical events together with a sense of personal dignity and self-awareness. • Stimulates communication skills, impaired due to AD, leading to

isolation because of inability to speak.

• Benefits up to advanced stages of AD.

• Reduction in frequency and extent of neuropsychiatric symptoms especially anxiety and depression. • Stimulates memory.

• Improved communication and personal autonomy.

Bright light therapy • Reduce circadian rhythm deregulation and likelihood of night-time disturbances and ‘sundown syndrome’, i.e. confusion/agitation in late afternoon/early evening.

• Bright light consists of a set of fluorescent bulbs installed in a box; patients sit close to the light box, with their eyes open, but not looking directly at light.

• Indication of changes in: agitation/ aggression; depression/dysphoria; aberrant motor behaviour; appetite/ eating disorders.

The discovery that amyloid β protein activates the complement system has indicated that inflammatory pathways somehow contribute to the pathogenesis of AD.40 This has resulted in studies exploring the use of anti-inflammatory agents in preventing and in slowing down the progression of AD. Studies showed that patients who were on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) were spared from AD, i.e. had reduced risk of getting AD. The longer the NSAIDS were used prior to clinical diagnosis, the greater the sparing effect.40 The mechanism behind this effect is not fully understood, however, some hypotheses accredit the regulation of cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and COX-2 as the driving force behind the effect, since COX-1 and COX-2 levels are elevated in AD patients.41 Lipid-lowering agents, especially the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A-reductase inhibitors, such as pravastatin and lovastatin (but not simvastatin) have been associated with lower prevalence of AD, and hence they may also be used to prevent the onset of AD.1

Medication such as cholinesterase inhibitors and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-receptor antagonists are quite effective in managing cognitive symptoms, whereas antipsychotics and

antidepressants are more effective in non-cognitive symptoms. Cholinesterase inhibitors, namely donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine, have been shown to improve cognition.1 Donepezil is a piperidine derivative which specifically inhibits acetylcholinesterase, but not butyrylcholinesterase. Rivastigmine acts centrally at acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase sites, but has low activity at these sites in the periphery. Galantamine is a cholinesterase inhibitor that also has activity as a nicotinic receptor agonist. Memantine is an NMDA-receptor antagonist which blocks glutamatergic neurotransmission, which may prevent excitotoxic reactions. It can be used as monotherapy, or in combination with a cholinesterase inhibitor. Their synergistic effect has been shown to improve cognition and activities of daily living.1 Antipsychotics, especially atypical antipsychotics, have been used to treat disruptive behaviours and psychosis in AD patients. Antidepressants, especially selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, have also been used to treat depression and anxiety in AD patients.1 Paroxetine, however, causes more anticholinergic side effects than the other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Tricyclic antidepressants are usually avoided due to their severe anticholinergic side effects.1

Table III: Pharmacological management in Alzheimer’s disease1,40-42

Drug class Drug Use Side effects

Co

gnitiv

e S

ympt

oms

Cholinesterase Inhibitors Donepezil Rivastigmine

Galantamine

Mild to moderate AD Donepezil also used for severe AD

Mild to moderate gastro-intestinal disturbances including; nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea, urinary incontinence, dizziness, headache, syncope, bradycardia, muscle weakness, salivation, and sweating.

Abrupt discontinuation may worsen cognition and behaviour in some patients.

N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-receptor antagonists

Memantine Moderate to severe AD Constipation, confusion, dizziness, hallucinations,

headache, cough and hypertension.

N

on-co

gnitiv

e sympt

oms

Antipsychotics (Atypical) Clozapine Risperidone

Disruptive behaviour and psychosis in AD

Somnolence, extrapyramidal symptoms, abnormal gait, worsening cognition, cerebrovascular events, hypotension and increased risk of death.

Antipsychotics (Typical) Haloperidol Disruptive behaviour and psychosis in AD

Antidepressants Paroxetine Venlafaxine

Depression and anxiety in AD Gastro-intestinal disturbances including; nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, abdominal pain, diarrhoea and constipation, anorexia, anaphylaxis, arthralgia, myalgia, dry mouth, insomnia, tremor, dizziness, hallucinations, drowsiness and urinary retention.

Long-t

erm pr

e-tr

ea

tmen

t -

pot

en

tial pr

ev

en

ta

tiv

e option

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS)

Ibuprofen Indomethacin

Patients at risk of developing AD (potential preventative option before cognitive impairment)

Gastro-intestinal disturbances including; discomfort, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and occasionally bleeding and ulceration, rashes, angioedema, bronchospasm, headache, dizziness, drowsiness, nervousness, depression, insomnia, vertigo, tinnitus, photosensitivity, haematuria and fluid retention.

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A–reductase inhibitors

Pravastatin Lovastatin

Patients at risk of developing AD (potential preventative option before cognitive impairment)

Conclusion

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia in older adults. The disease is extremely complex, with causes not fully understood. Patients progress through degenerative, irreversible phases of the disease, while cognitive functioning (memory, thinking and reasoning) and behavioural abilities are affected, up to the point where the person must depend completely on others for basic activities of daily living. Current pharmacological treatment used in the management of AD may ease the symptoms for a period of time, but do not stop the persistent downward progression of the disease. Patients may benefit from non-pharmacological strategies tailored to the needs of the individual person. Ongoing research indicated that specific precautionary measures, i.e. higher education and improved heart health, are most likely to delay the onset of AD. The urgent need for drug development is echoed by the words of Margaret Chan, the Director-General, World Health Organization “I can think of no other disease where innovation, including breakthrough discoveries to develop a cure, is so badly needed.” 4

References

1. Slattum PW, Peron EP, Hill A. Chapter 38. Alzheimer's Disease. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Posey L. eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach, 9e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2014:817-34.

2. Alzheimer’s Association. 2012 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(2):131-168. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2012.02.001

3. Wilson RS, Segawa E, Boyle, PA, et al. The natural history of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychol Aging. 2012;27(4):1008-17.

4. World Health Organization (WHO). First WHO ministerial conference on global action against dementia: meeting report. Geneva, Switzerland, 16-17 March 2015.

5. Prince M, Acosta D, Ferri CP, et al. Dementia incidence and mortality in middle-income countries, and associations with indicators of cognitive reserve: a 10/66 Dementia Re-search Group population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380(9836):50-8.

6. Prince M, Wimo A, Guerchet M, et al. World Alzheimer Report 2015. The Global Impact of Dementia. An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost & trends. Alzheimer's Disease Interna-tional, London, UK. 2015.

7. Tschanz JT, Norton MC, Zandi PP, et al. The Cache County Study on Memory in Aging: Fac-tors Affecting Risk of Alzheimer's disease and its Progression after Onset. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013;25(6):673-85. doi:10.3109/09540261.2013.849663

8. World Life Expectancy. World Health Rankings. [homepage on the Internet]. Available from: http://www.worldlifeexpectancy.com/world-rankings-total-deaths.

9. Alzheimer’s Disease International. Policy Brief for Heads of Government. The Global Impact of Dementia 2013-2050. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/GlobalImpactDementia2013.pdf. 10. Alzheimer’s Disease International. African Regional Conference calls to raise priority of de-mentia. 22 September 2016. Available from: https://www.alz.co.uk/news/african-regional-conference-calls-to-raise-priority-of-dementia.

11. Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, et al. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010-2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80(19):1778-83.

12. Sosa-Ortiz AL, Acosta-Castillo I, Prince MJ. Epidemiology of dementias and Alzheimer's dis-ease. Arch Med Res. 2012;43(8):600-8.

13. Chan KY, Wang W, Wu JJ, et al. Epidemiology of Alzheimer's disease and other forms of de-mentia in China, 1990-2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9882):2016-23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60221-4

14. Alzheimer’s Association. 2016 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(4).

15. Satizabal Cl, Beiser AS, Chouraki V, et al. Incidence of Dementia over Three Decades in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:523-32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504327 16. Prince M, Comas-Herrera A, Knapp M, et al. World Alzheimer Report 2016. Improving

healthcare for people living with dementia. Coverage, quality and costs now and in the future. Alzheimer Dis Int (ADI), London. 2016.

17. De Jager CA, Joska JA, Hoffman M, et al. Dementia in rural South Africa: A pressing need for

epidemiological studies. South African Med J; 105(3):189-190.

18. Radebe M. Higher than expected prevalence of dementia in South African urban black population. Media release, Media Liaison. 22 September 2010. Available from: http://www. ufs.ac.za/templates/archive.aspx?news=1871&cat=1.

19. Keene CD, Montine TJ, Kuller LH. Epidemiology, pathology, and pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease. In: UpToDate, DeKosky ST (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2016. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-pathology-and-pathogenesis-of-alz-heimer-disease?source=search_result&search=alzheimer&selectedTitle=2~150. 20. Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, et al. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer's

disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(8):788-94. 21. Banerjee S. Good news on dementia prevalence - we can make a difference. Lancet.

2013;382(9902):1384-6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61579-2

22. Tannenbaum C, Paquette A, Hilmer S, et al. A systematic review of amnestic and non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment induced by anticholinergic, antihistamine, GABAergic and opioid drugs. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(8):639-58.

23. Dekosky ST, Gandy S . Environmental exposures and the risk for Alzheimer disease: can we identify the smoking guns? JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(3):273-5.

24. Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Yu L, et al. Total daily physical activity and the risk of AD and cogni-tive decline in older adults. Neurology. 2012;78(17):1323-9.

25. Larson B. Risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia. In: UpToDate, DeKosky ST (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2016. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/risk-factors-for-cognitive-decline-and-dementia?source=see_link.

26. Van Cauwenberghe C, Van Broeckhoven C, Sleegers K. 2016. The genetic landscape of Alz-heimer disease: clinical implications and perspectives. Genet Med. 18(5):421-30. 27. Dong S, Duan Y, Hu Y, et al. Advances in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: a

re-evaluation of amyloid cascade hypothesis. Transl Neurodegener. 2012;1:18:1-12. 28. Dumanski JP, Lambert J, Rasi C, et al. Mosaic Loss of chromosome Y in blood is associated

with Alzheimer disease. Int J Hum Genet. 2016;98:1208-19.

29. Sherva R, Kowall NW. 2016. Genetics of Alzheimer disease. In: UpToDate, DeKosky ST (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2016. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/ genetics-of-alzheimer-disease?source=see_link§ionName=EARLY-ONSET%20ALZ-HEIMER%20DISEASE&anchor=H6562978#H6562978.

30. Pegueroles J, Vilaplana E, Montal V, et al. Longitudinal brain structural changes in preclini-cal Alzheimer disease. Alzheimers Dement. 28 Sep 2016;pii:S1552-5260(16)32890-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.08.010 [Epub ahead of print]

31. Mortamais M, Ash JA, Harrison J, et al. Detecting cognitive changes in preclinical Alz-heimer’s disease: A review of its feasibility. 1 Oct 2016;pii:S1552-5260(16)32901-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.06.2365 [Epub ahead of print]

32. Wolk DA, Dickerson BC. Clinical features and diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. In: UpToDate, DeKosky ST (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2016. Available from: https://www.uptodate. com/contents/clinical-features-and-diagnosis-of-alzheimer-disease?source=see_link. 33. National Institute on Aging (NIA). Caring for a Person with Alzheimer’s Disease Your

Easy-to-Use Guide from the National Institute on Aging. 2012. Available from: https://www.nia. nih.gov/alzheimers/publication/caring-person-alzheimers-disease/about-guide. 34. Nelson L, Tabet N. Slowing the progression of Alzheimer’s disease; what works? Ageing Res

Rev. 2015;23:193-209.

35. Schuster R. Alzheimer’s effects reversed in mice by targeting ‘bad’ gene, not plaque. Haaretz Daily Newspaper, 6 Oct 2016. Available from: http://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/science/1.746170.

36. Bettayeb K, Hoolo BV, Parrado AR. et al. Relevance of the COPI complex for Alzheimer's disease progression in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;13(9):5418-23. doi: 10.1073/ pnas.1604176113

37. Bettayeb K, Chaang JC, Luo W, et al. δ-COP modulates Aβ peptide formation via retro-grade trafficking of APP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(19):5412-17. doi: 10.1073/ pnas.1604156113

38. Cammisuli DM, Danti S, Bosinelli F, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for people with Alzheimer’s Disease: A critical review of the scientific literature from the last ten years. Eur Geriatr Med. 2016;7:57-64.

39. Amtul Z. Why therapies for Alzheimer’s disease do not work: Do we have consensus over the path to follow? Ageing Res Rev. 2016;25:70-84. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.09.003 40. McGeer PL, Rogers J, McGeer EG. Inflammation, antiinflammatory agents, and Alzheimer's

disease: The last 22 years. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54(3):853-7. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160488 41. Vlad SC, Miller DR, Kowall NW, et al. Protective effects of NSAIDs on the development of

Alz-heimer disease. Neurology. 2008;70(19):1672-7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000311269.57716.63 42. Rossiter D, ed. South African Medicines Formulary. 11th ed. Cape Town: Health and Medical