White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/1722/

Article:

Sloper, P., Greco, V., Webb, R. et al. (1 more author) (2006) Key worker services for disabled children: the views of staff. Health & Social Care in the Community. pp. 445-452. ISSN 1365-2524

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2006.00617.x

eprints@whiterose.ac.uk

Reuse

Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item.

Takedown

If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by

Key worker services for disabled children: the views of staff

Short title: Views of staff in key worker services

Authors: Veronica Greco, D. Phil., Social Policy Research Unit, University of York;

Patricia Sloper, PhD, Social Policy Research Unit, University of York;

Rosemary Webb, PhD, Department of Educational Studies, University of York;

Jennifer Beecham, PhD, Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent

at Canterbury.

This is the authors’ version of the article published as Greco, V., Sloper, P., Webb, R.

and Beecham, J. (2006) Key worker services for disabled children: the views of staff,

Health and Social Care in the Community, 14, 6, 445-52.

The definitive version is available at www.blackwell-synergy.com

Author to whom correspondence can be addressed:

Veronica Greco, Social Policy Research Unit, University of York, YO10 5DD

Tel: 01904 321950

Fax: 01904 321953

Abstract

Provision of ‘key workers’ for disabled children and their families, working across

health, education, and social services, has been recommended in the Children’s

National Service Framework. This study investigated the views of staff of key worker

services concerning the organisation and management of the services. Interviews

were carried out with key workers (N=50), managers (N=7) and members of

multi-agency steering groups (N=32) from seven key worker services in England and

Wales. A response rate of 62% was obtained. Major themes emerging from the

interviews were identified, a coding framework was agreed upon, and data were

coded using the qualitative data analysis programme Max QDA. Results showed that

although the basic aims of the services were the same, they varied widely in the key

workers’ understanding of their role, the amount of training and support available to

key workers, management and multi-agency involvement. These factors were

important in staff’s views of the services and inform recommendations for models of

service.

Key workers: key workers, care coordination, disability, children, multi-agency

working.

Introduction

Families with disabled children are in contact with many different agencies and

professionals. Many families report problems in understanding what services are

available and how to access them, understanding the roles of the different agencies

and professionals, getting professionals to understand their situation, and delays in

receiving services (Sloper, 1999). An answer to these problems, recommended in

official reports from the Court Report (1976) onwards, is that families should have

one person who acts as their main point of contact, collaborates with professionals

from their own and other services and ensures that access to and delivery of services

from the different agencies and professionals is co-ordinated. This person has been

termed a 'key worker', 'named person' or 'care coordinator. In this paper, the term key

worker is used.

Research has shown that less than a third of families with a disabled child has a key

worker (Beresford, 1995; Chamba et al., 1999) and when this does occur, it is often a

professional who takes on the role on their own initiative. Until recently, the

development of key working as part of a multi-agency system has been rare.

However, with the implementation of the Early Support Programme (Department for

Education and Skills/Department of Health, 2004) for families with young disabled

children, there has an upsurge of interest in key worker services.

A review of evidence on the effects of having a key worker (Liabo et al., 2001) has

shown that families with key workers report better relationships with services,

reduced stress, improvements in receipt of information and access to services, fewer

have reported that the role of the key worker encompasses: providing information

and advice to the family, identifying and addressing needs, accessing and

coordinating services for the family, providing emotional support, and acting as an

advocate for the family (Mukherjee et al., 1999; Tait & Dejnega, 2001).

A few studies have investigated views of staff in key worker services. Two studies

(Prestler, 1998; Tait & Dejnega, 2001) showed that there was an increase in job

satisfaction for those who acted as key workers. Other studies have looked more

broadly at professionals' views of the key worker service and their role in it. Appleton

et al. (1997) reported that key workers felt that they needed more time to dedicate to

care coordination and specific training for the role. In an evaluation of two key worker

schemes, Mukherjee et al. (1999) found that half the key workers saw no differences

between the key worker role and their everyday work. Key workers felt that the role

produced benefits in multi-agency working and improved relationships with parents.

However, difficulties were also encountered: not having enough time for the role,

confusion for staff and families about the key worker's role and, in one site, a lack of

training and supervision for key workers.

In a recent study exploring the impact of multi-agency working on professionals

supporting disabled children (Abbott et al., 2005), professionals from six care

coordination schemes, four of which provided key workers to families, were

interviewed. Results showed that overall, working with families as part of a

multi-agency team was felt to be enjoyable and rewarding. Professionals enjoyed better

relationships with families and could be more effective in supporting them.

to meet families’ needs, and they had broadened their own sense of role and identity,

although this sometimes raised concerns about erosion of expertise, and some

experienced uncertainty about the key worker role. Staff also reported that

multi-agency work did not appear to have a detrimental impact on their workload, although

there did not seem to be clear guidelines for staff on how much time commitment

should be made available to the care coordination service.

The aim of the study reported here was to investigate the views of staff from seven

key worker services which differed in their management and operation. This was part

of a larger project evaluating key worker services, involving parents, children and

staff in the services, and exploring the effectiveness of different models of service

(Greco et al., 2005).

Methods

Selection of key worker schemes

Seven key worker services were selected from 30 that were identified from a national

survey (Greco & Sloper, 2004). The rationale for selection of the seven services was

to represent variation in terms of models of service and types of locality covered.

Results of the survey indicated that an important difference between services was

the type of key workers employed, with non-designated key workers (who key work

for a few families on top of their ordinary role) being the most common (21 services),

and five services employing designated (full-time) key workers and three using both

types of workers. Thus, services were selected to reflect these different models: four

used only non-designated key workers, two used only designated key workers, and

funding to no dedicated funding; two services were longstanding and five were more

recently set up. Four of the catchment areas were predominantly rural, two were

predominantly urban, and one encompassed both urban and rural areas. Four of the

services were in England and three in Wales. The study aimed to investigate the

selected services as cases viewed from the perspectives of key workers, service

managers, and members of the steering group.

Procedure

The study was approved by a Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee. Packages,

each containing a cover letter, information sheet, response form and postage-paid

return envelope, were sent to managers of the services, who distributed these to key

workers and all members of steering groups. The project aimed to interview all

managers, up to 10 key workers and up to 8 members of steering groups in each

service. Where services included a large number of key workers, managers were

asked to send packages to 20 key workers from a variety of professional

backgrounds. Where services included large steering groups (over ten), packages

were sent to ten members, selected to cover a variety of backgrounds, including

parents. If willing to take part, recipients provided contact details on the response

form, and were contacted by researchers to arrange an interview. Interviews lasted

approximately one hour and, with participants' consent, were tape-recorded.

Interview schedules

The interview schedules set out a list of questions and possible prompts to guide

interviewers but were used flexibly in order to respond to the issues raised by the

interviewees.

Key workers were asked questions about: their professional background, typical day,

training and supervision received, and problems encountered.

Interviews with steering group members included questions about their role on the

steering group; procedures for steering group meetings; multi-agency involvement;

involvement of parents and children in setting up and overseeing the service; and

funding for the service.

Interviews with service managers covered: their professional background and role in

the service; history of the service; multi-agency involvement; parent and child

involvement in the service; and funding of the service. All interviewees were asked

about the role of key workers, advantages and disadvantages of the service and

suggested improvements.

Data analysis

The interviews were analysed following established qualitative analysis procedures

(Taylor & Bogdan, 1984). This involved three researchers each reading a set of

transcripts to identify major themes emerging from the interviews. A coding

framework was agreed and themes were coded, employing the qualitative analysis

and views of the different models of services and then comparing these. Initially, a

report on the interviews for each service was produced, and these were checked by

another researcher and sent to the service manager in the appropriate site for further

checking. These reports were then drawn together, identifying differences and

similarities between views in the different services for a full report on the study

(Greco et al., 2005).

Results

Sample

One hundred and fifty-five packages were handed out to service managers.

Ninety-six responses were received. This represents a response rate of 62%. However, in

two services, it was not clear whether all packs were distributed to staff. In addition,

eight respondents were not included as they exceeded the number of interviews

planned for their services. In one interview, the tape was faulty and could not be

transcribed. Eighty-seven interviews, between six and 16 per site, were analysed

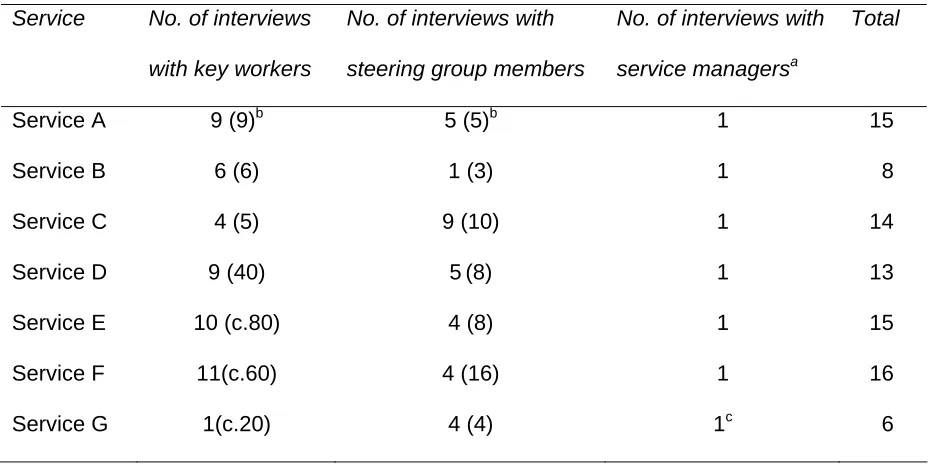

Table 1: Interviews conducted with staff

Service No. of interviews

with key workers

No. of interviews with

steering group members

No. of interviews with

service managersa

Total

Service A 9 (9)b 5 (5)b 1 15

Service B 6 (6) 1 (3) 1 8

Service C 4 (5) 9 (10) 1 14

Service D 9 (40) 5(8) 1 13

Service E 10 (c.80) 4 (8) 1 15

Service F 11(c.60) 4 (16) 1 16

Service G 1(c.20) 4 (4) 1c 6

a

In all sites except E, there was one service manager.

b

( ) = no. of key workers/steering group members in service

c

Joint interview with service manager and administrator who carried out much of the day to day running of the service.

Key workers came from a range of professional backgrounds. Social workers, health

visitors and community nurses were the most common professions, but therapists,

teachers, workers with voluntary agencies, Portage workers, nursery nurses, youth

workers, paediatricians and a dietician were also represented. In one service, a few

parents acted as key workers for themselves, supported by the service manager.

Service managers had professional backgrounds in health or social services.

Members of the steering groups included parents as well as representatives from all

Aims of the services

The basic aims of the services were similar across all seven services. These were:

identifying the needs of the child; providing key workers as a main point of contact for

the child and family; drawing up and reviewing a multi-agency care plan; working with

other professionals; providing information to families; and providing support for

families and helping them to access services.

Understanding of the key worker’s role

In four services, interviews with all staff showed clear agreement about what the key

worker role encompassed. These services defined the role as being the main source

of information, advice and support for families, enabling and empowering families,

overseeing and coordinating the implementation of the care plan and information

sharing between professionals. These services all had a clear written job description

for key workers. However, in the other three services different key workers

interpreted their role in different ways. Many key workers felt that the role was not

clear to them or they did not see any difference between the key worker role and

what they had always done. Some key workers expressed uncertainty about how

families and other professionals understood the role.

…and the key worker role I think is, is a little bit fuzzy, well I think

in everybody’s mind, certainly in mine.

In services where there were problems understanding the role, considerable

were clearly undertaking the role defined in earlier research (Mukherjee et al., 1999;

Tait & Dejnega, 2001) but others saw their role as more limited. Some did not feel

that they should be proactive in contacting families or that liaising with other

professionals on behalf of the family was part of their role. The following contrasting

accounts from workers in the same service illustrate this diversity in understanding:

I suppose my main idea of it is that it’s my responsibility to communicate

with all other professionals involved and make sure everyone’s up-to-date

…..and you’d like to feel that you’re the first person the family would turn to

if they’ve got worries. And I’d also feel a responsibility in getting the

problem sorted, even if it wasn’t in my area I would feel that was my job to

be acting as an advocate really for the family.

I’m not checking up on other professionals and their involvement in

families, that’s not my role.

Training

Three services had induction and regular ongoing training for key workers. Two

currently had no initial or ongoing training, although one of these had training

sessions in earlier years and plans were being made to reintroduce them. In another

service, some induction training was provided, consisting of one workshop when the

service first started; in the seventh service, each new key worker met the service

manager who explained the aims and nature of the service and what was expected

of them. This service manager also ran occasional sessions to explore key working in

In services with regular training, a wide range of topics was covered, including: law

relating to children, disability rights legislation, child protection, direct work, life story

work, charging policy, presentation skills, housing grants and benefits, Disability

Living Allowance, Motability, direct payments, statementing, the roles and working of

different agencies, what services are available and where to get information, and

team building. In addition to topics identified by service managers, key workers often

identified issues on which they required training and they spoke very positively about

the training received.

The training we've been given has been wonderful, it really has,

we've learnt a lot from it.

In services where key workers did not receive regular training, views were mixed.

Some felt that the training they received in their every day professional role was

sufficient; others expressed a need for training.

Supervision

The three services with regular training also had regular supervision specific to key

working. This was provided by the service managers between fortnightly and

six-weekly and was highly valued by the key workers.

It's excellent, you know. So...there are issues we go through,

issues about key working generally and, you know, the team, the

I need to, you know, I can go through every one of them and it's

really useful to say look I'm at loggerheads here, which she'll say

well have you tried doing that, you know.

In the other services, most key workers found that the supervision they received from

their line managers in their day-to-day professional role and support from other

professional colleagues was sufficient. However, some wanted more support and

guidance that related specifically to their key worker role.

Regular supervision was provided in services with between five and nine key

workers. In the larger services (40-80 key workers) the managers' contact with key

workers was more erratic. In some services, supervision was limited to the possibility

of telephoning the manager when a crisis occurred.

Peer support

In the three services that had key worker-specific training and supervision, there

were also regular opportunities for peer support. Members of two designated key

worker teams shared accommodation with each other, and one service with

non-designated key workers arranged regular training and group support meetings. Key

workers in these services particularly valued opportunities to meet and share

information and support. Key workers said having a diversity of professional

backgrounds in the team was an asset in providing a range of expertise. However

this synergy was possible only when key workers were given the opportunity to meet

Nobody knows everything and everybody has their weaknesses,

and that is the advantage of a true team where people are aware of

the weaknesses of others but they have their own strengths, which

compensate. So I think that’s the advantage of having people from

different disciplines…

Caseloads and contact with families

There was considerable variation in caseload size. Designated key workers

commonly worked with 20 to 40 families. In four of the services, non-designated key

workers worked with between one and five families in addition to their usual role and

caseload. In the other service, workers spent a greater proportion of their time on the

key worker part of their role and caseloads ranged from two to 25 families.

Key workers emphasised that the amount of time they spent on the key worker role

varied according to families’ levels of need at the time. Both designated and

non-designated key workers could struggle to cope if more than one family had a crisis at

the same time. Key workers found it difficult to estimate how much time they spent in

direct contact with families. Those who did make an estimate suggested that contact

with families took up about 25 to 50 per cent of their time, with related administration

and contacts with other services taking up the remainder.

Funding

Service managers and members of the steering group expressed that lack of funding

experiencing the most difficulties, there was no dedicated multi-agency funding for

the service. Managers and steering group members saw this as meaning that there

was no ownership of the service:

…but the problems have always been because no-one owns it,

there’s no money. I don’t know what it’s like in other areas but I

think my own view is that unless everyone’s on board with it then

it’s a very lopsided service…

Even where there was some multi-agency funding, problems could still arise over

which agency should fund resources or equipment needed by families. This was

frustrating for key workers who felt that these problems still needed to be sorted out

at strategic levels.

Where funding was committed from the three statutory agencies, inequities in

funding and the separation of funding streams, rather than pooled budgets, were

seen as barriers to good collaboration.

Role of the service manager

All services but one had a service manager who was responsible for the key worker

service. In three services, the role of the manager was to lead and develop the

service, supervise, support and organise training for key workers. In some cases,

managers also chaired planning and review meetings for children and families. Two

of these services had teams of designated key workers and one had both designated

related roles, however, it did not appear that these detracted from their management

of the key worker service. Supervision from these managers was highly valued.

They also saw developing a strong team spirit and motivating key workers as part of

their role and key workers valued this.

In one service with 40 non-designated key workers, the manager’s role included

organising planning and review meetings for families, chairing meetings, taking

minutes and preparing and distributing reports. She also provided support for key

workers and was regarded by them as very accessible and helpful. However, the

manager felt that it was not possible to provide regular supervision for such a large

number of key workers.

Service managers in the two remaining services had somewhat different roles. Both

had a role in overseeing the service but neither supervised, trained or had regular

contact with key workers. Both services had large numbers of non-designated key

workers (60-80). In one case, the manager chaired and coordinated planning and

review meetings for children, and some key workers felt that if a problem arose they

could contact the service manager. In the other case, one manager was responsible

for the implementation of four key worker teams in four areas of the county. Each

team had a manager, but responsibility for supervision of key workers rested with line

managers in their own agencies. Some key workers in this service felt that the team

managers were too busy to be contacted.

It was clear from interviews with key workers that accessibility of the service manager

was an important aspect of the service, but in non-designated key worker services

provide support or supervision and organise training.

Roles of the steering groups

In the initial stages of developing the services, multi-agency steering groups had

been instrumental in defining criteria and finding funding for the service. Most

continued to have a role in monitoring the service, reviewing and developing policies

and practices, and finding funding for new developments or expansion of the service.

A number of members highlighted the role of the group in ensuring a multi-agency

focus, raising awareness of the service in other agencies and addressing barriers to

multi-agency working.

All groups met regularly, varying between quarterly and once every two weeks.

However, in two areas there were concerns about poor attendance. Replacing

agency representatives who had left their agencies was identified as problematic in

both areas. In one area, poor attendance was also attributed to the fact that the

service was well established so people did not feel the need to prioritise the

meetings. In the other, there were concerns about lack of representation from some

agencies which meant that decisions could not be made, and it was felt that there

was a need for involvement from higher levels of management so that decisions

could be acted upon. In two areas, the groups' responsibilities were much wider than

the key worker service and the service was only a small part of the agenda.

Parent and child involvement

Five steering groups had between two and eight parent members per group, one

parent members but was planning to have parent representation. Nine parents were

interviewed in their capacity as steering group members. In all services, parents were

seen as an important force in keeping the group ‘grounded’, focussing on things that

affect families most, and providing a user perspective on the service. Generally,

parents felt that their views were listened to and respected, but a few suggested that

in reality they had little power and those who ‘hold the purse strings’ are the real

decision makers. None of the groups had children or young people involved,

although in one scheme young people had been involved when initially planning the

service. In one scheme, children were too young to be involved in consultation. In the

others, the high level of expertise and the considerable amount of time and effort

required to involve disabled children and young people in consultation meant that this

had not yet taken place. However, four groups were currently looking at ways for this

to happen.

Constraints and problems of the key worker role

A consistent theme among non-designated key workers was having insufficient time

to devote to the role. Many did not have dedicated key working time, and some felt

they were not doing justice to either role. Other constraints were engendered by gaps

in the provision of services in the areas and lack of resources. Problems in making

contact with other professionals, both to pass on and to obtain information, were

common. Some key workers felt that it was difficult to get other professionals to

understand their role and liaise with them.

Where key workers did not have regular supervision in their key worker role, lack of

support was at times problematic. Lack of relevant information and knowledge was a

confusion about the role of the key worker was cited as a problem in three areas.

Type of key worker: designated or non-designated

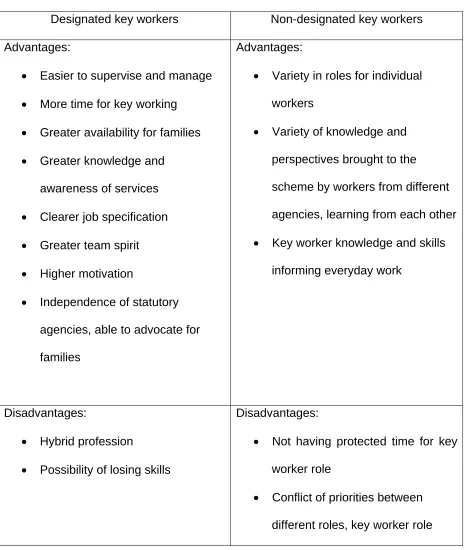

Views on the advantages and disadvantages of designated and non-designated key

[image:20.595.67.535.225.775.2]workers are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2: Advantages and disadvantages of different types of key workers

Designated key workers Non-designated key workers

Advantages:

• Easier to supervise and manage

• More time for key working

• Greater availability for families

• Greater knowledge and

awareness of services

• Clearer job specification

• Greater team spirit

• Higher motivation

• Independence of statutory

agencies, able to advocate for

families

Advantages:

• Variety in roles for individual

workers

• Variety of knowledge and

perspectives brought to the

scheme by workers from different

agencies, learning from each other

• Key worker knowledge and skills

informing everyday work

Disadvantages:

• Hybrid profession

• Possibility of losing skills

Disadvantages:

• Not having protected time for key

worker role

• Conflict of priorities between

taking second place

• Not being 'an expert in everything'

• Not using key worker skills all the

time

• Uncertainty about role

• Little contact with other key

workers

• Juggling two roles

• Failure to know difference

between two roles

The disadvantages identified for designated key workers were seen as a risk of the

role but had not been experienced by the key workers interviewed. Some of the

disadvantages identified for non-designated workers may be overcome by better

management of the services, for example, by having a clear job description, training

and supervision, and agreements on protected time for key working with line

managers.

Advantages, disadvantages and suggested improvements to the service

Key workers identified a number of advantages for themselves: opportunities to build

good relationships with families; being able to 'make a difference' for families;

learning new skills and increased knowledge about children and families and other

services; and developing effective frameworks for information exchange with other

Perceived advantages for families of having a key worker were centred around

having one person to contact about any concerns, someone who was in charge of

coordinating services and making sure needs were met, and not having to keep

telling their story to different professionals. Respondents felt that this resulted in

greater consistency and continuity of care and thus stress was alleviated.

Advantages of the service for other professionals also centred around having one

point of contact regarding a family, being a source of information and knowing what

all agencies were doing with regard to a family. Key workers were seen as ‘lightening

the load’ and reducing pressure on other professionals.

Most of the disadvantages mentioned for key workers themselves concerned

non-designated key workers (see above). It was also acknowledged that key working is a

demanding role, key workers were at risk of becoming too emotionally involved and

having appropriate support in the role was important.

Improvements needed in some services were already valued features of other

services. These include:

• Clear description of the role of the key worker

• Administrative support

• Regular training and supervision for key workers

• Register of information about services for key workers and families

• Opportunities for key workers to exchange information and experiences

• A manager who can devote time to supervising the service.

There were some improvements that none of the services had fully managed to

achieve. Non-designated key workers wanted protected time for key working and, in

some cases, more negotiation with their line managers about how much time they

could spend on their key worker role and reductions in case loads in their main jobs

to allow this. Some services recognised the need to involve children and young

people in planning the service but none had done this as yet, and key workers

wanted guidance on consulting with disabled children and young people.

Discussion

The research is timely given the recent emphasis on providing key workers for

families with disabled children in the Early Support Programme (Department for

Education and Skills/Department of Health, 2004), the Children's National Service

Framework (Department of Health/Department for Education and Skills, 2004) and

Improving the Life Chances of Disabled People (Cabinet Office, 2005).

Findings show similarities with Abbott et al's. (2005) study on the impact of

multi-agency working on professionals. For example, Abbott et al. showed that clear

guidelines on the nature of the key worker role were often not available and having

peer support with key workers from other professional backgrounds was helpful.

However, that study found that key workers did not report a detrimental impact on

their ability to manage their workload. On the contrary, staff in this study found key

working required extra time and effort, and lack of time to perform this role was a

The findings of the study must be viewed in the context. The study is limited to a

snapshot in time and some of the services will already have changed by expanding

their staff or instituting training. The services in this study were focused on disabled

children with complex needs and we are not able to comment on issues concerning

key working for other groups of children. In addition, interviewees were self-selecting

and interviews with steering group members were difficult to achieve in one service

and in another only one key worker agreed to be interviewed. Potentially a more

varied perspective might have been obtained in services where a higher proportion of

staff was interviewed. However, overall there was a wide range of views within and

between staff in the different services.

The study showed that although the basic aims of the services were very similar, the

processes used to achieve those aims were different. Many staff were positive about

the advantages of the services for families and for themselves. However, there were

some crucial differences between services affecting how well they were viewed and

the problems encountered by staff. Services varied in the understanding of the key

workers’ role, the amount of training key workers received, whether they received

supervision or not, their opportunities to meet other key workers, level and stability of

funding, and the roles of the service manager and steering group.

Based on these findings, a number of recommendations can be made. Having a

clear, written job description for key workers helps to clarify the key worker role for

key workers themselves and other professionals. Key workers also need to have a

clear understanding of their role in order to explain it to parents, so that families know

showed that in services where there was confusion among key workers about the

role, parents were equally confused and different parents had very different

experiences of the same service (Greco et al., 2005).

Key working crosses the boundaries of different agencies and disciplines. The key

worker is the main point of contact for families, and needs to have a broad

knowledge of disability, other agencies' and professionals' roles, what services are

available locally and nationally, and where to find information. The role can also be

very demanding, and support structures need to be in place for key workers. These

include specific and ongoing training focused on the key worker role; supervision

specific to the role; opportunities for contact with other key workers; and agreement

on time for key workers to undertake the role. The findings suggested that the service

manager plays a central part in leading and developing the service and supporting

key workers, and needs sufficient time for running the service.

Staff in services with no dedicated funding spoke of the problems of lack of

ownership of the service and it is clear that dedicated funding, at least for a manager

and a training budget, is crucial. Steering groups could provide strong multi-agency

backing for the service and facilitate collaboration. However, managers on these

groups should be senior enough to make decisions, and able to prioritise steering

group meetings. Efforts must be made to ensure that parent representatives on the

steering group have a say in decision-making and do not feel powerless when

The findings indicate that staff in services where the above factors were in place

were most positive about the service. Where they were not in place, they were

identified as improvements needed in the service. Professionals interviewed in this

research generally felt that, as indicated in earlier research (Liabo et al., 2001), key

working was a way of providing a better and more effective service. However, with

the recent growth in key worker services (Care Coordination Network UK, 2005) it is

References

Abbott D., Townsley R., & Watson D. (2005) Multi-agency working in services for

disabled children: what impact does it have on professionals? Health and Social Care

in the Community 13, 155-163.

Appleton P., Boll V., Everett J.M., Kelly A.M., Meredith K.H. & Payne T.G. (1997)

Beyond child development centres: care coordination for children with disabilities.

Child: Care, Health and Development 23, 29-40.

Beresford B. (1995) Expert Opinions: a national survey of parents caring for a

severely disabled child. Policy Press, Bristol.

Cabinet Office (2005) Improving the Life Chances of Disabled People. Prime

Minister's Strategy Unit, London.

Care Coordination Network UK (2005) Survey of care coordination schemes.

www.ccnuk.org.uk

Chamba R., Ahmad W., Hirst M., Lawton D. & Beresford B. (1999) On the Edge:

minority ethnic families caring for a severely disabled child. Policy Press, Bristol.

Court Report (1976) Fit for the Future: The Report of the Committee on Child Health

Department for Education and Skills/Department of Health (2004) Early Support:

Professional Guidance. DfES Publications, Nottingham.

Department of Health/Department for Education and Skills (2004) National Service

Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services: Disabled Children

and Young People and those with Complex Health Needs. Department of Health,

London.

Greco V. & Sloper P. (2004) Care coordination and key worker schemes for disabled

children: results of a UK-wide survey. Child: Care, Health, and Development 30,

13-20.

Greco, V., Sloper, P., Webb, R. & Beecham, J. (2005) An Exploration of Different

Models of Multi-Agency Key Worker Services for Disabled Children: Effectiveness

and Costs. DfES Publications, Nottingham.

Liabo K., Newman T., Stephens J. & Lowe K. (2001) A Review of Key Worker

Systems for Disabled Children and the Development of Information Guides for

Parents, Children and Professionals. Office of R&D for Health and Social Care,

Cardiff, Wales.

Mukherjee S., Beresford B. & Sloper P. (1999) Unlocking Key Working. Policy Press,

Prestler B. (1998) Care coordination for children with special health needs,

Orthopaedic Nursing March/April (Supple.)

Sloper P. (1999) Models of service support for parents of disabled children: What do

we know? What do we need to know? Child: Care, Health and Development 25,

85-99.

Tait T. & Dejnega S. (2001) Coordinating Children’s Services. Mary Seacole

Research Centre, De Montfort University, Leicester.

Taylor S. & Bogdan R. (1984) Introduction to qualitative research methods: The

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the Department of Health, Department for Education and

Skills, HM Treasury, and Welsh Assembly Government. The views expressed here

are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funders. We would like to

thank all the staff who gave their time to participate in interviews, Sheila Sudworth

who carried out some of the interviews, and the project advisory group who provided