RIT Scholar Works

Theses

Thesis/Dissertation Collections

6-30-1998

ABA/Lovaas treatment for autism and pervasive

developmental disorders in the Monroe County

area

Kelly Byrne

Follow this and additional works at:

http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses

This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion

in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact

ritscholarworks@rit.edu.

Recommended Citation

ABA/-

Lo.w.a,s

1

ABA/ Lovaas Treatment for Autism and Pervasive Developmental

Disorders in the Monroe County Area

Master's Project

Submitted to the Faculty

of the School Psychology Program

College of Liberal Arts

ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

By

Kelly

J.

Byrne

In

Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of

Rochester, New York

June

30, 1998

Approved: _ _....;:.:Je:.:..;n:.:..:n~ife~r...;;;L~u~ko~m~s;.;.;k~i

:--

:--_

(Comm ittee.. Chair)

Nicholas DiFonzo

School Psychology Program

Permission to Reproduce Thesis

jf\

K

~

VY\v

f\

(cJ

£

(,{ )V\

V"\k-r----=:...!..:...~e...::.~~---I

k!

fld

J

~

A1<.1

Aff~

hereby grant permission to the

Wallace

Me~bra';ymhe

Rochester Institute of Technology to reproduce my

thesis in whole or in part. Any reproduction will not be for commercial use or profit.

Date:

tR

I

~

I

q

~

Signature of Author:

PERMISSION FROM AUTHOR REQUIRED

Title of thesis

_

I

prefer to be contacted

each time a

request for reproduction is made. I can be reached at the following address:

PHONE:

_

Date:

_

Signature of Author:

_

________________________________________________________________________________~~ O O__~"_._.Q~~Q_0 _

I

PERMISSION

DENIED

TITLE OF THESIS

_

I

hereby deny permission to theWallace

Memorial Library of the Rochester Institute of Technology to reproduce my

thesis in whole or in part.

ABA^

Lovaas 2

Table

ofContents

List

ofTables

andFigures

/

4

Abstract

/

5

literature

Review

/

6

Introduction

/

6

Autism

/Pervasive

Developmental Disorder

/

7

Description

ofLovaas

Therapy

/

8

History

ofLovaas

Therapy

/

11

Controversy Surrounding

Research

andLovaas Behavioral

Interventions/

15

Current Legal Issues

/

16

Introduction

to

Other Treatment

Approaches

/

17

Rational

for

Project

onABA/

Lovaas

Treatment

for

Children

withAutism/

19

Project

Overview

/

22

Community

Contribution

/

22

Project

Design

andReview

ofObjectives

/

24

Rptuilts/DiqnistJnrL

Section./

29

Sample Demographics

/

29

Applied Behavior Analysis Programs

/

31

Additional Treatment Methods

/

39

Making

the Decision to

Use ABA

/Lovaas

/

41

ABA

/Lovaas'Impact

onthe

Family

/

45

Positives

andNegatives

ofABA /Lovaas

/

45

What Parent's

Need From

the

Monroe

County

Community

/

46

Parent's Experiences

withFunding

ABA /Lovaas Programs

/

46

Summary

/

47

References^

49

Appendix A:

Letter

from

RACE

Group

/

54

Appendix B:

ABA/Lovaas Parent

Survey

/

56

ABA/

Lava

a^s4

List

ofTables

1.

Sample

Demographics

/

30

2.

Information

onApplied Behavior Analysis

Programs

/

32

3.

Reasons

for

Change in Program Hours

/

34

4.

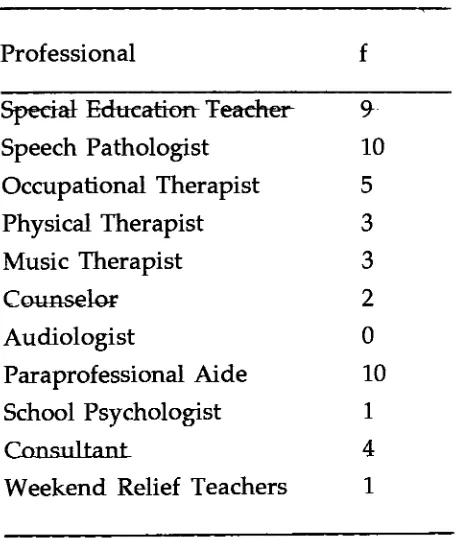

Professional

Composition

ofABA

Teams

/

37

5.

Consultant Hours

/

38

6.

Other Treatment Programs

/

40

7-

Source

ofEirst

Laformation-

on-ABA

/

42

8.

Reasons

for

Choosing

ABA/

Lovaas Treatment

/

43

Abstract

The

purpose ofthis

project wasto

provide schoolpsychologists,

and otherprofessionals,

an overview ofthe

ABA/

Lovaas

programsbeing

implemented

in

the

Monroe

County

area(upstate

New York). Parents

weresurveyed,

in

orderto

gatherinformation

onthe

Applied Behavior

Analysis/

Lovaas

methodthey

areusing

to

treat

their child.To

provide additionalinformation

aboutthe

childrenparticipating

in

the project,

adirect

observation ofthe

child was conducted and arating

scale wascompleted

(Childhood

Autism

Rating

Scale). Ten families

participatedin

the

project,

with the child's agesranging

from

37

monthsto

66

months.Project

resultsindicate

that

parent's areinvesting

large

amounts oftime

andenergy

in

these

programs.

In

allcases,

parents reportedcombining

ABA/Lovaas

programs withother

forms

oftreatment

(i.e.,

preschool,

drug

therapy,

musictherapy,

dietary

treatments,

etc.).Parents

aregenerally reporting

positivefeelings

aboutthe

treatment,

althoughthey

areexperiencing

some concerns around programfunding,

ABA/

Lovaas

6

Literature

Review

Introduction

"Scarcely

a monthhad

passed sinceAnne-Marie's

first diagnosis [of

autism],

but

it

felt

morelike

six.Every

single nightMarc

andI

readbooks

and articles aboutautism,

racing

againstthe

days,

racing

to

find

someway

ofhalting

her

inexorable

progressionbackwards"(Maurice,

1993).

The

above words were writtenby

Catherine

Maurice,

author ofthe

book Let

Me Hear Your

Voice.

Ms.

Maurice

writes ofthestruggle she andher

family

faced

while

trying

to

find

away

to

help

their autisticdaughter. These

words couldhave

been

writtenby

any

parentfacing

the

struggle ofraising

andeducating

a child withautism.

The Maurices

optedto teach

Anne-Marie

using behavioral

principals,

specifically

the

behavioral

educational plandeveloped

by

O.

Ivar

Lovaas. In

her

book

she writes ofthe

success and gainsboth

ofher

autistic children made whentaught

by

this

method.In

additionto

Ms. Maurice's

descriptive

account ofher

children's

recovery,

casestudy

articleshave

been

printed onthe two

siblings(Perry,

Cohen,

&

DeCarlo,

1995b). Although

professionalsin

the

field

have

warnedthe

public notto

viewthe

Maurices'

progress as

typical,

her book has become

a catalystfor many

parentsto

research andemploy

Lovaas

methods withtheir

children(Shapiro

&

Hertiz, 1995; Ryan,

1995).

As

more and more children arediagnosed

with autism/Pervasive

Developmental Disorder

(PDD),

the

question ofhow

to

treat

the

disorder

becomes

more urgent.

In

the

Monroe

County,

located in

upstateNew

York,

parents and professionals areturning

to

treatments

based

onbehavioral

principles(Applied

treatment

methodsbecome

morepopular,

county

agencies and schooldistricts

arefaced

withthe

challenge offunding

the

programs anddeciding

whobenefits

from

such services.

This has

created muchcontroversy

and muchdiscussion

overthe

appropriateness and effectiveness of

Lovaas/

ABA

programs.Autism

/Pervasive Developmental

Disorder

Fifty

yearsago,

Leo Kanner identified

"autism" as a syndrome ofdisorders

characterized

by

socialisolation,

language

problems,

and a restricted range ofinterests

(Bauer,

1995a &

1995b;

Diagnostic

andStatistical Manual Fourth

Edition,

1994).

Autism

has been

misunderstood andclinically hard

to

define.

Historically

it

was considered a

"childhood

schizophrenia,"and

thought

to

be

causedby

poorparenting (Rutter

&

Schopler,

1987).

Other

theories

onthe

"single

coredeficit" of

autism are

that

it is

causedby

sensory

difficulties,

biological

problems,

language

andcognitive

deviances,

and socialimpairments

(Smith,

McEachin,

&

Lovaas,

1993).

Today,

autismis

seen asexisting

more on a spectrum(Rimland,

1993;

Wing

&

Gould,

1979).

The

term

Pervasive Developmental Disorder

(PDD)

is

frequently

usedto

describe

the

range andseverity

ofthe

"autistic

like"symptoms a child

displays

(Rutter

&

Schopler,

1992).

Many

researchersfeel

that

there

is

no singleetiology

for

autism,

and childrenmay

have different

impairments

that

arecausing

the

autisticcharacteristics

(Wing

&

Gould, 1979;

Phelps &

Grabowski, 1991;

"Interview

withIvar

Lovaas,

1994).

In

1980,

autism was recognized as adistinct developmental

disorder

in

the

DSM-III

(Bauer,

1995a & 1995b).

Initially,

autism was placed onAxis

II,

indicating

that

it

wasconsidered astable,

unchanging

conditionthat

had

a poorprognosis.In

ABA/

Lovaas

8

transient

conditions(Edelson).

This

movement,

along

withthe

acceptanceby

many

professionals ofthe"autism

spectrum"has

resultedin

more childrenbeing

diagnosed

as autistic orPDD

(Bauer,

1995a

&

1995b). Treatment

modalitieshave

been

revisedto

address abroader

range ofbehaviors

associated withautism,

but

nosingle

therapeutic

intervention has

yetbeen

identified

asthe

"cure"for

autism.As

aresult, the

professionalcommunity

andfamilies

of children with autism aregrappling

withthe

choice of whattreatment

strategiesto

use.Description

ofLovaas

Therapy

Behavioral

treatments,

such asthat

developed

by

Ivar

Lovaas,

arebased

ontheories

of operantconditioning

and appliedbehavior

analysis(ABA) (Lovaas,

1981). Rutter

describes

it

as"a

matter of ....encouraging

progressin

the

rightdirection

through the

use ofdifferential

reinforcement and ofdirect

teaching

that

providethe

skillsneeded"

(1985).

Techniques

such asshaping, prompting,

fading,

extinction,

andthe

use ofprimary

andsecondary

reinforcers are usedto

teach the

child a wide range ofbehaviors

and skills(Rutter,

1985; Lovaas,

1981). In

addition,

Lovaas

endorsedthe

use ofaversives,

particularly

to

end self-injuriousbehavior.

The ABA

approachto

teaching

children with autism stemsfrom

the

belief

that

they

do

not appearto

learn

from

their

environmentlike

typical

childrendo. While

the

average child

takes in information

continuously

(every

waking

minute,

365

days

ayear),

the

child with autism needsto

be

taught the

skillsto

learn

from

the

world aroundthem.

The

structure andintensity

ofthe

Lovaas

programis

an attemptto

teach them

basic

learning

principals,

andto

"make-up"for lost

learning

time

(Lovaas,

1987;

Lovaas,

1981).

philosophy,

techniques,

and educational programsthat

arethe

foundation

for

today's

Applied Behavior Analysis

(ABA)

approachto

treating

autism.The book

is

organized

into

five

sections,

which are asfollows:

(1)

Unit I

teaches

parents andteachers

the

basics

of appliedbehavior

analysistechniques,

(2)

Unit II

containsprograms

(of

individual

lessons)

that

preparethe

childto

learn,

(3)

Unit III

introduces

basic

verballanguage

andplay

skills,

(4)

Unit IV

teaches

self-help

skills,

(5)

Unit V

presents more advanced and complicated verballanguage,

(6)

Unit

VI

focuses

on abstract verballanguage,

and(7)

Unit

VII

teaches the

studenthow

to

function

in

school andcommunity

settings.Parents

are advisedto

order a series ofvideo

tapes,

to

help

supplementthe

instructions

containedin

the

training

manual(Lovaas,

1981).

Although

parents are consideredthe

main serviceproviders,

it is

recommended

that

they

develop

a"treatment

team"

of at

least

three

peopleto

help

provide services

to their

child("Lovaas

revisited: should wehave

everleft?,

1995;

Lovaas

1981). Parents

andtreatment teams

are guidedby

a consultanttrained

in

Lovaas

/ABA

therapy.

Each

programis

designed

to teach

suchthings

assitting,

receptivelanguage,

and verbal

imitation. Within

each program are smaller stepsthat

they

child mustmaster

before

the

skillis learned.

These

smaller steps are called"discrete trail

training,"

because

they

start with ateacher's

instruction

and end withthe

child'sresponse

(Lovaas,

1981).

A

well coordinatedteam

mustensure,

by

the

use of videotaping

orby

direct

observation, that

they

are allusing

the

same commands and samelanguage

whileteaching

the

child(Lovaas,

1981).

In his

originalstudies,

Lovaas

recommended

that

the

child receive a-minimum-of 40-hours-

ofdirect

one-oiv-Qneinstruction

per week(Lovaas,

1987).

As

willbe

discussed,

the

evolution ofABA

ABA/

Lovaas, 10

instruction is

appropriatefor

eachindividual

child.Discrete

trial

training

consists ofthree

components.They

are asfollows:

"

(1)

presentation of a

discriminative

stimulus(i.e.,

a request or acommand);

(2)

aresponse

(what

the

individual does

following

the

request orcommand);

and(3)

presentation of

reinforcing

stimulus,

defined

in

this

program as a rewardif

correct,

saying

"no"if

incorrect"("Lovaas

revisited: should we everhave

left?,"1995).

Although individual

needsvary from

childto child,

instruction

usually

consists of4

to

6

hours

perday,

5

to

7

days

perweek,

for

a minimum oftwo

years.Within

asession

the

child might workfor

2

to

5

minutes,

andthen

be

rewardedfor working

appropriately

anywherefrom

several secondsto two

minutes .After

eachhour,

the

child

is

generally

given a15 to

20

minutebreak

("Lovaas

revisited: should we everhave

left?/'1995^.

Lovaas^

L981X-

ba

orderto

makethismodel work,,it is.

essentiaLforparents and

teachers

to

identify

whattypes

ofthings

are "rewards"for

their

child.Some

children mightbe

willing

to

workfor

food,

while others will preferbeing

rewarded

for

the

opportunity

to

engagein

some physicalactivity

(Lovaas,

1981).

Another

emphasis ofthe

Lovaas

methodis

early

intervention. Lovaas

proposed

in

his first

study

(1973)

that

the

youngerthe

childwas,

the

better

progressthey

would make(Lovaas,

Koegel, Simmons,

&

Long,

1973).

Some

researchershave

suggested

that

thisis

true

because

the

brain

plasticity

of younger childrenis

greaterthan that

of older children(Perry,

Cohen,

&

DeCarlo,

1995a).

Early

intervention

is

successful

for

avariety

ofreasons,

such as:(1)

Early

development

is

a criticaltime

to

acquire communication

skills,

for both

the typical

child andthe

child withautism;

(2)

Younger

childrenhave limited

learning

histories,

andtheir

behaviors

areless

complex;

(3)

Since

younger children need much care andattention,

parents arechildren are easier

to

physically

control(Dunlap

&

Fox,

1996).

Although

Lovaas'book does

notdelineate

anideal

ageto

startbehavioral

intervention,

in

his 1987

study he limited his

subjectsto

children under the age of40

monthsif

mute,

and underthe

age of46

monthsif

echolalic.Most

childrenin

ABA

programs are aroundthe

age of3 1/2

years("Lovaas

revisited: should we everhave

left?,"1995).

As

willbe

discussed,

there

is

muchcontroversy

over what agethe

child stops

benefiting

from

intensive behavioral

intervention.

Although

it

wasthought

to

be

appropriateonly

for

young

children,

researchers arestarting

to

suggestit

may benefit

older autistic students as well("Intervention:

it

doesn't

needto

be

early,"

1995).

History

ofLovaas

Therapy

O. Ivar

Lovaas

had many

years of experienceworking

with children withautism

before

he

presentedthe

ABA

program asit

existstoday.

He

dedicated his

professional careerto

researching

andtreating

children with autism.When Lovaas

first

began his

research,

he

wasinterested in

learning

abouthow

acquiring language

effects a child's non-verbal

behavior

(Lovaas,

1993). While

searching

for

agroup

ofchildren who were

lacking

meaningfullanguage,

Lovaas

wasintroduced

to

childrenwith autism.

From

that

point onhis

careerfocused

ontreating

andresearching

this

population.

(Lovaas,

1993).

Using

his

training

as abehavioral

clinicalpsychologists,

Lovaas

workedto

establish empirical evidenceto

supporthis

claimthat

abehavioral

method ofintervention

wasthe

best way

to

improve

the

lives

ofthese

children

(Lovaas,

1993).

Using

behavioral

principalsto

educate childrenis

nota new concept.Researchers

have found

behavioral

techniques to

be

effective withtypical children,

ABA/

Lovaas,

12

revisited: should we ever

have

left?,"1995). Lovaas

acknowledgesthat

his

approachto

treating

autismis

notbased

on newlearning

techniques

(Lovaas,

1993).

As

willbe

discussed,

his

programis

most notablefor

its

intensity

and structureddelivery.

Various

treatments

have been developed

to

help

children with autism(i.e., "play

therapy,

operantconditioning,

specialdiets,

megadoses ofvitamins,

psychoactivedrugs,

electricshock,

signlanguage

training,

residentialtreatment,

perceptualtraining,

motortraining,

mainstreaming,

specialeducation,

andothers")

(Schopler,

Mesibov,

&

Baker,

1982).

However,

many

professionals agreethat

using

abehavioral

approachto

treating

autismholds

the

most promise(Rutter,

1985;

Lovaas,.

1987;

"Lovaas

revisited: should we everhave

left?,"199,5).

Lovaas'

first

attemptto

usebehavioral

principalsto treat

children withautism

had limited

success(Lovaas, Koegel, Simmons,

&

Long,

1973).

In 1973

Lovaas

designed

abehavioral

programto treat

20

children with autism.Specific

ages ofthe

children

involved in

the

study

were not reportedin

the

literature.

Students

wereidentified

onthe

basis

of apparentsensory

deficits,

affectiveisolation,

self-stimulatory

behavior,

mutism,

echolalicspeech,

and a poor receptivelanguage

(Lovaas,

Koegel, Simmons,

&

Long,

1973).

The

use of aversives(such

asspanking,

aslap

onthe

thigh,

or aloud

"no")

was usedto

eliminate self-injuriousbehavior

(Lovaas,

Koegel, Simmons,

&

Long, 1973; Lovaas,

1993).

The

children were placedin

four

treatment

groups.The

groups variedin

the

intensity

ofthe

treatment

delivered,

amount ofinstruction

they

received,

and whodelivered

the treatment

(therapist

vs. parents).Overall,

the

study

suggestedthat

whentaught

using behavioral

principles,

subjects made great gains

in

learning

appropriatebehavior

and communicationmade

during

treatment.

Lovaas

concludedthe

following:

(1)

Age

may

be

animportant

factor

in

determining

which childrenbenefit

from behavioral

treatment.

Lovaas

noted thatthe

older childrenin

his study

had

difficulty

withgeneralizing

new skillsto

different

environments.He

proposedthat

younger children would

"discriminate

less

wellthan

olderchildren,

hence

generalize and maintain

the therapeutic

gainsto

a more optimal degree"(Lovaas,

Koegel, Simmons,

&

Long, 1973);

(2)

The

treatment

is

most successfulif

it

nrnirsin

rhp rhild's nahiralenvironment.

The

childrenin

the

study

who returnedto

stateinstitutions

aftertreatment

regressedto

a greaterdegree

than

children who returnedhome

to

parentstrained

in

behavioral

techniques.

(Lovaas, Koegel,

Simmons,

&

Long,

1973).

Lovaas

concluded

that

the

environmentthe

childfunctions

in.

mustbe

structured sothat

it

maintains

the therapeutic

gains madeby

the

childduring

treatment;

and(3)

Parents

canbe

utilized astreatment therapists.

As

mentionedabove,

the

parents

trained

in behavioral

techniques

helped

their

children maintaintreatment

gains.

Lovaas identified

the

following

parent characteristics as essential:"A

willingness

to

usestrong

consequences...,

a willingnessto

deny

that

their

childrenare'ill'

[put

responsibility

onthe

child]...., the

willingnessto

commit a major part oftheir

lives

to their

children andto

exercise somedegree

of contingent managementthroughout

the

day"(Lovaas,

Koegel, Simmons,

&

Long,

1973).

Lovaas

appliedthis

knowledge

to

his

1987

study.The

Young

Autism

Project

began in

1970

atthe

University

ofCalifornia

atLos Angeles

(UCLA).

Subjects

wereassigned

to

an experimentalgroup

and a controlgroup,

onthe

basis

ofthe

availability

of staff members.Random

placement was not ethical or acceptableto the

ABA/Lovaas,

14

with autism

from

atreatment

program not connectedto

UCLA. Participants

had

achronological age of

less

than

40

monthsif

they

weremute,

andless

than

46

monthsif

they

possessed echolalic speech.Intelligence

was also afactor.

Participants

had

aprorated mental age

(deviation

IQ)

of11

months or more.The

childrenin

the

experimental

group (n

=19)

received over40

hours

ofintensive

behavioral

treatment

per weekin

the

home,

for

a minimum oftwo

years.An

emphasis wasplaced on parent

involvement

and parent education.The

childrenin

controlgroup

#1

(n

=19)

received10

hours

ofbehavioral

treatment

perweek,

and wereinvolved

in

community based

interventions

(special

education,

preschool).The

childrenin

control

group

#2

(n

=21)

were nottreated

by

any

professionals associated with theYoung

Autism Project

(Lovaas,

1987).

The

results ofthis

study

wereto

create muchcontroversy among

professionals who specialized

in

autism(Schopler,

Short,

&

Mesibov,

1989; Foxx,

1993;

Kazdin,

1993;

Mesibov,

1993;

Mundy,

1993

).

Lovaas

claimedthat

out ofthe

19

subjects

in

the experimentalgroup,

9

children,

or47%

ofhis

sample,

achievednormal

functioning. Normal

functioning

was measuredby

placementin

a regulareducation

first

gradeclassroom,

andby having

averageintellectual

functioning

(as

measured

by

a standardizedtest).

In

Control

Group

#1,

only

one student achievednormal

functioning.

In 1993

anotherstudy

was conductedto

look

atthe

long

term

effects,of

Lovaas'

method of

behavioral

intervention.

(McEarhin,.

Smith, &_Lavaas,

1993;

"Long

term

follow-up:

early

intervention

effectslasting,"

1993).

Approximately

six years after

the

participants ofthe

1987

study

achieved"normal

functioning,"they

were evaluated

to

assessif

the

gainsthey

made were permanent.Only

one studentfrom

the

best

outcomegroup

neededto

be

movedfrom

a regular education classto

aautism was successful and created permanent positive change

(McEachin,

Smith,

&

Lovaas, 1993;

"Long

term

follow-up: early

intervention

effects lasting,"1993).

Controversy

Surrounding

Research

andLovaas Behavioral

Interventions

Although

Lovaas'claim of a

47%

success rate generated muchexcitement,

it

also generated much controversy.Concerns

and additional explanations aboutLovaas'

research, andmethods si i rfa rpd

in

thrppmain areas:(a)

Assignment

to the

Experimental

Group

was notRandom. One

ofthe

major criticisms of

the

1987

study

wasthat

subjects were not assignedto

the

experimentalgroup

or controlgroup

in

a randomfashion

(Schopler,

Short &

Mesibov,

1989).

Schopler, Short,

andMesibov

(1989)

questioned whether or notthe

controlgroup

was comparableto

the

experimentalgroup, in

terms

of parentalinvolvement

andthe

amount of attentionthey

received.(b)

Subjects

Not

anAverage Sample

ofChildren

withAutism.

Schopler,

Short,

andMesibov

(1989)

madethe

argumentthat

Lovaas

choose agroup

of subjectsthat

had

abetter

prognosisthan

the

average population of children with autism.The

claimhas

been

madethat tests that

generally

yieldlow

scoresfor

children with autism were chosenfor

pretreatmentdata

collection.His

samplehad

an average

IQ

higher

than

the

average child with autism.The

older childrenin

the

study (40

monthsto

46

months)

were chosenonly

if

they

were echolalic(generally

considereda sign of abetter

prognosis).(c)

Follow-Up

Measures

Did

notMeasure "Normal

Functioning."

Several

professionals

have

questioned whether"school

placement,

standardizedIQ

measures^

andasranHarHi7pHsocial/

emotionalmeasure"

were

true

measures,of whether or notany

residual autistic characteristics remained(Schopler,

Short,

andABA /Lovaas

16

many

flaws,

because districts vary

in

their

inclusion

andmainstreaming

policies.In

addition,

many

ofthe

childrenin

the

"best

outcome"group had strong

parent andteacher

advocates(Foxx,

1993; Schopler, Short,

andMesibov,

1989).

Lovaas

was alsocriticized

for

overlooking

several elevated scores onthe

social/emotional

measurethat

suggestedthese

studentshad

some emotional and cognitive problems(Mundy,

1993).

In

various responsearticles,

Lovaas

has

answered each concern raisedby

other professionals

(Lovaas,

Smith,

&

McEachin, 1989; Lovaas,

1993). In

many

instances

he

refersback

to

his

original research as evidencethat

his

methodologieswere sound.

Although

there

is

controversy

over the47%

success rate ofthe

1987

study,

all professionals agreethat the

study

needsto

be

replicated andimproved.

As

of1993,

three

replication sites were established acrossthe

country

(Smith,

McEachin,

&

Lovaas,

1993).

There

aremany

concerns aboutreplicating,

such asthe cost, the

length

oftime that

mustbe

dedicated

to the

study,

andthe

lack

of professionals whohave

intensive

training

in

behavior

modification(Smith,

McEachin,

&

Lovaas,

1993).

In

a1993

article,

Alan

Kazdin

proposedthat

replication studies shouldhave

the

following

things:

(1)

Random

assignmentto the

experimentalgroup

and controlgroup;

(2)

A

larger

samplesize;

and(3)

Use

of a standarddiagnostic

battery

thatsamples a

full

range ofdisorders

and evaluatesthe

severity

ofthe

child's autisticfeatures.

(Kazdirv

1993).

Current

Legal Issues

As

was mentionedpreviously,

Lovaas

programshave

createdlegal issues

for

parents and school

districts.

According

to

PL94-142,

districts

are requiredto

provideall students with

"Free

andAppropriate Public

Education"

(FAPE)

("When

methodologies

collide,"

the

issue

of whatis

an "appropriate" and effective programfor

children withautism.

Due

to the

intensity

and specializedtraining

ofthe

Lovaas

consultants,

ABA

programs are costly.

It is

reportedthat

in

Maryland

programs can rangefrom

$20,000

to

$22,000

at year("Requests

for Lovaas

therapy,"1995). In California

services canrange

from $1,000

a monthto

$6,000

amonth,

depending

uponthe

expertise ofthe

consultant

("Requests for Lovaas

therapy,"1995). Although

the

decision

about whatconstitutes

FAPE

is

left up

to

state agencies andlocal

schooldistricts,

many

parentsare

initiating

due

process andentering

into impartial

hearings

("When

methodologies

collide,"

1995).

If

parents can convince ahearing

officerthat

the

Lovaas

methodis

superior and more effectivethan

programs providedby

the

district,

they

are awarded reimbursement and/or

funding

for

their

home-based

therapy

("When

methodologiescollide,"

1995). As

parents startto

winthese

hearings

(i.e.,

Delaware

County

Intermediate Unit

v.Martin

andMelinda

K.

andMA.

v.Vorhees

Township

Board

ofEducation),

districts

arefaced

withchoosing

between

costly

court expenses orfunding

an expensive program with unknowneffectiveness

("Requests

for

Lovaas

therapy,"

1995).

Introduction

to Other Treatment Approaches

As

was mentionedpreviously,

there

aremany

treatment

choicesfor

autismand

Pervasive Developmental Disorder.

Many

parents choose avariety

of strategiesto

addresstheir

children'sneeds.In

additionto

Lovaas/

ABA

therapy,

they

may be

utilizing

otherinterventions. The

following

is

adescription

of some ofthe

morepopular

treatment

choices:(A)

Psychopharmacology

(Drug

Treatment).

The

purpose ofusing drugs

to

control autistic

symptomology is

to

better

prepare the childto

respondto

specialABA/

Lovaas

18

Drugs

are usedto

increase

attention,

reduceself-stimulatory

behavior,

and reducetantrums

(Campbell,

Anderson, Deutsch,

&

Green,

1984).

The

drugs

most often prescribedinclude

the

following:

haloperidol,

fenfluramine,

naltrexone,

clomipramine, clonidine,

and various stimulants(Campbell,

Schopler, Cueva,

&

Hallin,

1996).

(B)

TEACCH. Treatment

andEducation

ofAutistic

and relatedCommunication

handicapped

Children. This

is

a program establishedby

Eric

Schopler

of theUniversity

ofNorth Carolina

atChapel Hill

(Campbell,

Schopler,

Cueva,

&

Hallin,

1996).

Schopler is

skeptical ofthe

dramatic

"recovery"claims

made

by

Lovaas

("Requests for

Lovaas,"1995).

The TEACCH

programis

acommunity

based

program,

located

in

public school classrooms.The

maintenants

ofthe

programinclude

high

amounts of parentparticipation,

on-going

evaluationand

diagnostic

work,

and structuredteaching (Schopler,

1987; Campbell,

Schopler,

Cueva,

&

Hallin,

1996).

(C) Auditory

andSensory

Integration Training. These

theories

arebased

onthe

premisethat

some people with autismhave

anover-sensitivity

orunder-sensitivity

to

sounds and/or

textures.

Through

variousinterventions

andactivities,

an attemptis

madeto

"desensitize"the child,

and makethem

better

ableto

handle

different

soundfrequencies

andtextures

(Campbell,

Schopler,

Cueva,

&

Hallin,

1996).

(D)

Greenspan Techniques.

Stanley

Greenspan

views autism as a"multi

systemdevelopmental

disorder,"

in

whichthe

child experiencesdelays

across allareas of

development

("Alternatives

to

behaviorism,"

1995).

He

advocatesfor

atherapy

called"floor

time,"

in

which the parent ortherapist

attemptsto

understandself-stimulatory

behavior)

("Alternatives

to

behaviorism,"1995).

The

childis

thought to

learn

through the

interaction,

andthrough

the

relationship

that

is

developed

during

time

spent withthe

adult("Alternatives

to

behaviorism,"1995).

(E)

Dietary

/Vitamin

Interventions. Of

allthe

areasdiscussed

thus

far,

this

area

is

the

mostcontroversial andlpast

rpsparrhpd,Most

ofthe

information

available on

this treatment is

found

onthe

internet

(Lewis,

1997). The

premisebehind

this treatment

is

that

one ofthe

causes of autismis

anallergy

to

gluten andcaseine.

These

two

substances arefound

in

many foods commonly

introduced

atthe

age of

approximately

18

months.Advocates

ofthis treatment

claimthat

whenfoods

with gluten and caseine are removed

from

the

child'sdiet,

many

oftheir

autisticsymptoms abate

(reduction

in tantrums

andself-stimulation,

improved

eye-contact,

better

attentionskills)

(Lewis,

1997). The

diet

is

often usedin

conjunction withvitamin

therapy.

Two

vitamin supplementscommonly

administeredin

large

amounts

include

B6

anddimethylglycine

(DMG) (Aman,

1995).

Rational

for

Project

onABA

/Lovaas

Treatment

for Children

withAutism

The

changing

definitions

for

autism andPervasive Developmental Disorder

(PDD)

have

resultedin

the

development

ofmany

treatment

options.Parents

ofpreschoolers

diagnosed

with autismface

the

challenging decision

of whatinterventions

to

use withtheir

child.As

indicated

by

the

aboveliterature

review,

O.

Ivar Lovaas has developed

a program whichis

based

on principals ofApplied

Behavior

Analysis,

consists of alarge

amount oftreatment

hours

(40+

perweek),

and

demands

intense

parentalinvolvement.

This

treatment

approachhas

createdmuch

controversy,

for

both

professionalsin

the

field

and schooldistricts.

With

the

increasing

number of childrenbeing

diagnosed

with autism/PDD,

it

ABA/

Lovaas,

20

over

the

course oftheir

career.In

orderto

serve as a consultant and source ofinformation

for

these

families,

professionals needknowledge

ofthe

history

andcurrent structure of

ABA

/Lovaas

programsin

the

Monroe

County

Area.

Due to

the

expense ofthese

intensive

programs,

schooldistricts

andcommunity

groups areraising

questions aboutthe

effectiveness and appropriateness ofthis treatment.

Community

groups and school professionalshave

startedto

collaborate onresearching

these

programs(i.e.,

Community

Task Force

onAutism:

Research

andEvaluation

Cnmmiftpp)

This

project was conductedin

orderto

provide professionalsin

the

field

anoverview of

both

the

composition ofthe

currentABA

/Lovaas

programsbeing

implemented

in

the

Monroe

County

area,

and asummary

ofthe

collective concernsof parents

implementing

such programs.The

literature

reportsthat

ABA/

Lovaas

programs aretime intensive

(40

hours+),

require much parentinvolvement,

and arebest

utilizedwith younger children.I

wantedto

assessif

these

characteristics aretrue

ofMonroe

County

families utilizing

these

programs.Parents

of children withautism

/PDD

weresurveyed,

using

asurvey

form developed

by

the

research student.The

children wereobserved,

and ratedin

terms

ofthe

severity

oftheir

autisticsymptoms

(Childhood

Autism

Rating

Scale).

The information

wasthen compiled,

in

orderto

get adescriptive

account ofthe

ABA/

Lovaas

programsin the

Monroe

County

area.In

addition,

as a school psychologistworking

in

this

community,

I

wantedto

have

abetter

understanding

ofthe

following:

(1)

What

sourcesdo

parents consultwhen

choosing

anABA/

Lovaas

treatment

programfor

their

child?;

(2)

What

professionals areincluded

onABA

/Lovaas

treatment

teams?;

(3)

What

otherdoes

ABA impact

family

life?;

(5)

What

do

parents needfrom

the

professionalcommunity?;

and(6)

What is

the

(approximate)

cost offunding

ABA/

Lovaas

programs?

This

knowledge

willhelp

schoolpsychologists,

and other professionalsABA/ Lovaas,

22

Project

Overview

Community

Contribution

With

the

rising

number of requestsfor

ABA

/Lovaas

treatments

for

autism,

professionals

in Monroe

County

have begun

to

ask questions aboutthe

efficacy

andcost-effectivenessof such programs.

Monroe

County

is

the

secondlargest county

in

upstate

New York. It's

populationis

approximately

750,000

people,

with aland

areaof

663.21

square miles.The

county

is

comprised of19

towns,

10

villages,

andthe

city

of

Rochester.

Rochester,

New York

is

famous for

its

exportindustry

(Eastman

Kodak,

Bausch

andLomb,

General

Motors, Xerox,

ITT Automotive).

On

a per capitabasis,

more products are exportedfrom

Monroe

County

than

any

othercommunity

in

the

United States

(above

information

located

athttp://www.co.monro.ny.us/

aboutmc

/

mchistory

.html).Through

professionalnetworking, in October

of1996 I

learned

of a committeeforming

to

addressthe

issue

ofABA

/Lovaas

servicesin

the

Monroe

County

area.A

group

ofprofessionals,

consisting

ofadministrators,

schoolpsychologists,

andspecial education

coordinators,

werecollaborating

to

gatherdata

and start somepreliminary

research onABA

/Lovaas

programs.The

chairpersonfor

this

committee was affiliated with

New

York's

Board

ofCooperative

Education Services.

In November

of1996 this

group

metto

formulate

their

purpose anddraft

up

asurvey.

They

intended to

look

at whattypes

of programs children whohad

receivedABA/

Lovaas

were placedin

uponentering

the

public school system.The

committeewanted

to

determine if

children who receivedABA

/Lovaas

as preschoolers weretypically

placedin

regular education or mainstreamedprograms,

ordid

they

stillThey

collectedthis

data

via a written survey.Each

committee member committedto

contacting

aMonroe

County

schooldistrict

andeliciting

their

cooperationin

providing

thedesired information.

As

willbe discussed

later,

some ofthe

questionsfrom

this

originalsurvey

were utilizedin

the

course ofthis

project.The

researchmethod and

survey

results were notutilized,

due

to the

fact

that

program placementcan

be

highly

subjective andinfluenced

by

many factors (such

asdistrict

policy

andthe

level

of parent advocacy).While

attending

this

November

24,

1996

meeting

I

learned

of anotherlocal

committee

forming

to

addressthe

issue

ofABA/

Lovaas. This

committee was calledthe

Community

Task Force

onAutism:

Research

andEvaluation

Committee. The

chairperson

for

this committee was affiliated withthe

University

ofRochester

/Strong

Hospital's Center

for

Developmental

Disabilities.

Although

the

make-up

ofthe

committee variedfrom meeting

to meeting, the

primary

memberswere as

follows:

two

parents of children withautism, two

pediatricians connectedto

the

Strong

Center

for

Developmental

Disabilities,

aNYS Board

ofCooperative

Educational

Services

(BOCES)

representative,

aCommittee

ofPreschool Special

Education

chairpersonfrom

aMonroe

County

schooldistrict,

and a schoolpsychologist

from

aMonroe

County

schooldistrict. I

attendedthree

meetings ofthis

committee

(December

20, 1996;

January

27, 1997;

January

31,

1997). The intent

wasto

work with

these

professionalsin

orderto

draft

up

a specific research questionthat

would

be

appropriatefor

a master's project onABA

/Lovaas

treatment

for

autism.This

provedto

be

achallenging

task.

The

long

term

objective ofthis

committee was

to

researchthe

effectiveness ofABA /Lovaas

programs asthey

compare

to

moretraditional

ways oftreating

autism(predominantly

specialABA/

Lovaas

24

limitations

in time

and personalresources, this

was not afeasible

researchtopic.

Through

much negotiation anddiscussion,

the topic

waslimited

and narrowed.It

was

decided

that

I

would conduct a series ofinterviews,

rating

scale observations(Child

Autism

Rating

Scale),

and recordreviews,

in

an attemptto

generate a generalidea

ofhow

much progress each childhas

made whilereceiving

Lovaas

therapy.

The

design

ofthe

final

project willbe discussed

at alater

point.In

orderto

gainthe

support ofMonroe

County

parents,

I

attended severalReaching

Autistic Children

Early

(RACE)

support groups.The

purpose ofthis

organization

is

to

promoteABA

/Lovaas

as a viabletreatment

optionfor

childrenwith autism.

They

provide support andinformation

to

families

implementing

ABA

programs.

The

long-term

goal ofRACE is

to

establish anApplied Behavior Analysis

school

for

children with autism.This

organization provided an excellent pool offamilies for

the

researchthat

wasto

be

conducted.On

February

1,

1997 1

presentedmy

projectdesign

to

the

parents present atthe

meeting.On

May

3,

1997

I

contactedthe

RACE

presidentfor

assistancein

promoting

my

project.The

president signed aletter

ofsupport,

andhad

parentssign-up

if

they

wereinterested in

participating

in

the

project(see

Appendix

A).

On

October

11,

1997

1

attended athird

RACE

meeting.At

this

meeting

I

scheduledfamilies

to

be

interviewed

and observed.Throughout

the

course ofthe

project,

close contact was maintained withthe

RACE

group

president and various members.

Project Design

andReview

ofObjectives

The

design

ofthis

project changed overthe

course ofits

completion.The

original

design,

mentionedabove,

was a series ofinterviews,

observations(CARS),

and recordreviews.

The

goal wasto

comparethe

length

oftime

the

child receivedmeasured

by

adifference

score,

obtainedby

comparing

the

child's score onthe

Childhood Autism

Rating

Scale

(CARS)

priorto

receiving

ABA

andto

the

child'sscore on the

CARS

afterbeing

in

anABA

program.Again,

due

to

limitations

oftime

andpersonal

resources, the

projectwas altered.During

the

period oftime

from

October,

1997

to

December, 1997,

interviews

and observations offamilies using

the

ABA

program were conducted.The information

gathered was usedto

develop

adescriptive

picture ofMonroe

County

ABA

programs.The

rating

scales were usedto

examine the

level,

orseverity,

ofthe

disability

demonstrated

by

this

particulargroup

of children with autism.

As

wasdiscussed

earlier, the

purpose ofthis

project wasto

give professionals and parents a "cross-section" or

description

ofthe

ABA

servicesbeing

delivered

to

children with autism/PDD

in

the

Monroe

County

Area.

The

Childhood

Autism

Rating

Scale

was administeredto

supplementthis

description,

and

to

provide some more specificinformation

aboutthis

sample of childrenreceiving

ABA

therapy.

The

originalintent

ofthe

project wasto

stay

withinthe

age range of3

to

5

years old.

After

consultation withprofessionals andparents,

it

wasdecided

that

amore appropriate age range was

birth

to

5

years old.Members

ofthe

Monroe

County

Committee,

The

Community

Task

Force

onAutism: Research

andEvaluation

Committee,

andthe

RACE

group

estimatedthat there

wereapproximately

50

children with

autism/

PDD

classifications withinMonroe County. It

wasthen

estimated

that

out ofthose

50

families,

approximately

30

ofthem

wereimplementing

ABA

programs.These

numbers were rough estimates.Due

to

thefact

that

there

are no centralizedrecordskept

onlocal

incident

rates of autism/PDD,

oron

the

enrollment of such childrenin

treatment programs,

estimations neededto

be

ABA/

Lovaas,

26

At

the

RACE

meetings(May

andOctober),

14

families

signedup

to

be

partofthe

project.Another 21

families

were contactedby

phone(personal

conversation orphone message).

For

various reasons(i.e.,

child wastoo

oldfor

the

study,

child wasno

longer

doing

ABA,

child wasmultiply

disabled,

parent never returnedthe

phonecall,

parentstoo

busy,

etc.),

only

11

families

wereinterviewed

and observed.Out

ofthese

11

families,

10

were usedto

calculatethe

descriptive

account ofABA

treatment

in

the

Monroe

County

area.One

childinterviewed

and observedby

the

researchstudent was out of

the

birth

to

5

age range.Interviews

and observationstypically

took

approximately

onehour

andfifteen

minutes.After

the parent(s)

completedthe

survey, the

research studentinterviewed

them

in

orderto

gather additionalinformation

to

accurately

scorethe

Childhood

Autism

Rating

Scale

(CARS).

The interview

wasdesigned

to

be filled

outby

the

parent whilethe

Childhood Autism

Rating

Scale

(CARS)

observation wasbeing

conductedby

the

research student.

The

average completiontime

ofthe

survey

was ahalf-an-hour

to

forty-five

minutes.The

questionnaire consisted oftwenty-four

questions,

withresponses

being

recordedin

narrativeform

andin

check-listform

(see

Appendix

B).

During

the

development

ofthe survey,

feedback

was collectedfrom

the

two

parentson

the

Community

Task

Force

onAutism: Research

andEvaluation

Committee.

As

previously

mentioned,

questions wereborrowed from

the

Monroe

County

survey

on program placement

for

preschoolers who receivedABA

treatment.

Care

wastaken

to

makethe

survey'slanguage

andformat

accessibleto the

parent.Questions

included the

following:

demographic information

onthe child,

number of monthsin

anABA

program,

number ofhours

ofABA

servicedelivered

weekly,

othertreatment

approachesbeing

utilized,

andthe

parentsimpression

ofdifferent facets

The Child Autism

Rating

Scale

(CARS)

was chosen as a measure ofthe

children's autistic symptoms.

The

scale consists of15

subscales:"relating

to

people;

imitation;

emotionalresponse;

body

use;

objectuse;

adaptationto

change;

visualresponse;

listening

response;

taste,

smell,

andtouch

response anduse;

fear

ornervousness;

verbalcommunication;

non-verbalcommunication;

activity

level;

level

andconsistency

ofintellectual

response;

and general impressions"(Van

Bourgondien,

1992;

Schopler,

1995). The

scale wasdeveloped

to

assistin

evaluating

children-referred

to the

Treatment

andEducation

ofAutistic

and relatedCommunication

handicapped

Children

(Division

TEACCH; Schopler,

1995).

The

CARS is

a compilation of several accepteddefinitions

anddescriptions

of autism.Schopler

drew

from

the

following

existing

criteria:"Kanner

(1943)

criteria,

the

Creak

(1961)

points, the

definition

ofRutter

(1978),

that

ofthe

National

Society

for

Autistic

Children

(NSAC,

1978),

andthe

DSM-IV

(1994)"(Schopler,

1995).

The

scale wasoriginally

createdin

1973,

andthen

revisedin 1988

(Schopler,

1995). The

manualused

for

this

projectwas reprintedin 1995.

The

norm samplefor

the

Childhood

Autism

Rating

Scale

(CARS)

was1,606

children,

reflecting

the

economic and racialmake-up

ofthe

North Carolina

population

that

TEACCH

services(Schopler,

1995).

As

reportedin

the manual,

theCARS has

adequatelevels

ofinternal

consistency

(.94),

interrater

reliability

(.71),

test-retest

reliability

(.88),

and criterion-relatedvalidity

(.80) (Schopler,

1995).

The

scale was

intended to

be

used as part of afull

evaluationfor

the

TEACCH

program.The

scale was scored after a cliniciandirectly

observed a child withinthe

laboratory

setting

(Schopler,

1995).

In

orderto

determine

if

the

scale was valid and reliableunder other circumstances,

further

studies were conducted.It

wasfound

that ratingsABA/

Lovaas,

28

and after record review

(r=.82),

adequately

correlated with ratingsdone

atTEACCH

Centers

(Schopler,

1995). For

thisproject, the

scale was scored afterdoing

adirect

observation of

the

childin

the

home

andinterviewing

the

parent.The CARS

was notthe

only

instrument

availableto

ratethe

severity

ofautistic symptoms.

Other

measures usedfor

this

purposeinclude

the

Autism

Behavior Checklist

(ABC)

andthe

Real Life

Rating

Scale

(RLRS).

A

pilotstudy done

by

Sevin

et al.(1991)

analyzedthese three scales, in terms

ofinterrater

reliability,

correlations

between

the

instruments,

accuracy

of cut-off scoresfor

classification,

and

the

relationship

ofthese

scalesto

adaptivebehavior

measures.Sevin

et al.(1991)

reportedthat

the

interrater

reliability

they

achievedfor

the

CARS

wasslightly

less

than

originally

reportedby

Schopler

(1995).

The

CARS

alsodid

not correlatewell with

the

adaptivebehavior

measure(Vineland).

The

authors attributedthese

discrepancies

to

a small sample size and adifference

in

behaviors

assessedby

the

Vineland

andthe

CARS. As

for

correlationsbetween

the, scales, the.

CARS

correlatedwith

the

RLRS,

but

notthe

ABC. The

cut-off scorefor

the

CARS

appearsto

be

appropriate,

asindicated

by

the

fact

that

92%

ofthe

subjects werecorrectly

identified.

The

authors conclude thatthe

CARS

andthe

RLRS

are adequatescreening

measurefor

identifying

children with pervasivedevelopmental

disorders

(Sevin,

1991). The

ABC fared less

well,

and wasconsideredless

"technically

sound"

than

the otherscales

(Sevin,

1991).

This CARS

was chosenfor

this

projectbecause,

when comparedto

otherinstruments,

it

is time

efficient andtechnically

superiorto

other autismDiscussion/Results

Section

Sample

Demographics

The

original goal of this project wasto

interview

and observe30 families.

Due

to

personallimitations

and parentavailability, the

final

sample size was10. This

sample size

is inadequate

to

make generalizations aboutthe

entireMonroe

County

area population of childrenwith autism.

Observations

willbe limited

to

this

uniquesample of

families

and children withautism/

PDD.

As

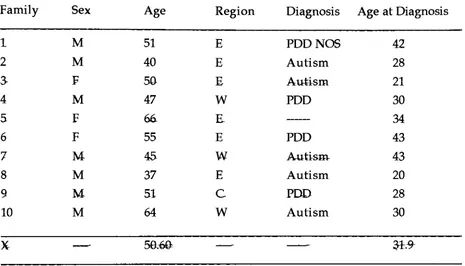

shownin Table

1, 30%

ofthis

sample was

female,

and70%

was male.Pervasive Developmental Disorders

mostfrequently

occurin

males(75%),

asis

reflectedin

this

particular sample(Schopler,

1995). Another

factor

I

attemptedto

look

at was wherein

Monroe

County

these

services are

being

delivered

withthe

mostfrequency.

Sixty

percent ofthe

families

live in

the

eastern part ofthe county,

30%

ofthe

families live

in

the

western part ofthe

county,

and10%

ofthe

families live

in

the

city

ofRochester.

The

average age ofdiagnosis

for

this

sample was31.9

months(with

a range of22

months;

youngest =21

months and oldest =43

months).The

average ageis in

accordancewith

the

DSM-IV

criteriafor

diagnosing

autism/PDD

before

the

age of3

years

(DSM-IV).

Two

childrenin

the

sample werediagnosed

afterthat

cut off point.As

for

the

specificdiagnoses

assignedto these

children,

they

included Pervasive

Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise

Specified,

(PDD

NOS),

Pervasive

Developmental Disorder

(PDD),

andAutism.

This

mostlikely

reflectsthe

"autism

spectrum,"

and

broadening

ofthe

definition

for

autism(Rimland,

1993; Bauer,

1995a

& 1995b).

The different

classifications reflectthe

heterogeneous

nature ofthis

population and

the

overalldifficulty

withdiagnosis.

Lovaas

(1973)