Theses

Thesis/Dissertation Collections

12-22-1977

My Snapshots

Arnold Sorvari

Follow this and additional works at:

http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses

This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion

in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact

ritscholarworks@rit.edu.

Recommended Citation

Arnold Sotiva.nl

Candidate

for

the

Master

ofFine

Arts

Degree

in

the

College

ofFine

andApplied Arts

ofthe

Rochester

Institute

ofTechnology

ZkX.2.{

Advi.A2.si:

Fl2.d2.siA.ck

R.

M2.y2.fi

December

22,

1977

It

Ia

not uAualto

worktoward

an advancedde.Qti2.2- In

a new{leld

a{terdecadeA

o{

a careerIn

another{leld.

Such

adven-tatiou^nc^i,

couldreadily

yieldtxa.Ap2.ttatX.0n,

l{

nottttauma,

but

I

have

been

fortunate.

It

haA

InAtead

producedjoy

andexciting

InAlgktA

,Including

Aome valuable. oneAInto

Aelfi-dlAclpllne.I

amparticularly

gratefulthat

my

workhaA

btiought

meto

thlA

patitlculatiCollege,

andInto

adialogue

withItA

unique andtalented

{acuity.

The

atmoAphereol

the.

uncommon,

Aepatiated,

graduatepainting

AtudlohaA

pttovldedhaven

{rom

workaday

concernA and aAtlmulatlng

memberAhlp

Into

awonderfully dlvetiAe

company

o{

fellow

palntetiA .My

pro^eAAlonal

poAltlonIn

aAlbllng

College

atthlA

InAtltute

Ia

highly

valued,

having

madethe.

participationIn thlA

ptLogttam poAAlbleboth

phyAlcally

andeconomically

.Encouragement

by

both

admlnlAtttato

ttA and colleagueAhaA

been

genettouA .Even

Aomeoft

my

colleagueA'puzzlement

that

a long-committed photographer Ahould

devote

Auch attentionto

the

"adverAary" arto&

painting

haA

Aerved aA adelightful

AtlmuluA.The

abAorblng

Atruggleofi

making

paintedImageA

andthe

accompanying

reAearch whichthlA

paper reportAhave

combinedInto

a newkind

ofi

experience{or

me.The

dlAcoverleA

wlll--lthlnk--make me a

better

teacher

In

that

other "adverAary"fileld.

ThlA

TkeAlA

reportdealA

with whatIa

the

moAt valuableImage-making

experienceo{

my

llfie.

The

perAonalquality

o{

that

experiencerequlreA

frequent

uAeo{

the

{IrAt-perAon

pronoun,

whichI

hope

the

reader will accept aAIndication

o{

the

IntenAlty

o{

my

perAonal excitement.

PREFACE

Ill

LIST

OF

ILLUSTRATIONS

INTRODUCTION

1

PRIMITIVISM

3

NAIVE

REALISM

ROUSSEAU

MORANVJ

PERSPECTIVE

11

TO

THE

BEGINNINGS

TWO

KINVS

Of

SPACE

ILLUMINATION

HOW

IT

WORKS

REALISM

40

PHOTO

REALISM

PAINTERL1NESS

T0REGR0UNV1NG

SUMMARY

52

QEUVRE

55

THE

MECHANICS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

75

[1]

Curvilinearity

ofRetinal

Image

13

[2]

The

Vanishing

Axis

System

20

[3]

A

Fully

Curvilinear

Perspective

system21

[4]

Synthetic

andArtificial

Perspective

23

[5]

Ground-Plans

ofSome

Perspective

Systems

24

[6]

The

Annunciation

oft

the

Death

o{,

the

Virgin

26

[7]

The

VeAcent

{rom

the

CroAA

27

[8]

The

Arrival

otf

the

Emperor

CharleA

IV

29

[9]

The

ConAtructlon

ofa

the

Temple

o^

JeruAalem

30

[10]

Leonardo's

Theory

31

[11]

Flat

andSpherical

Planes,

One-Point

Perspective.

. .33

[12]

"Normal"Wide-Angle

Photograph

34

[13]

Lateral

Synthesis

ofSuccessive

Fixation

Points

...37

[14]

Vertical

Synthesis

ofSuccessive

Fixations

38

[15]

"Fish-Eye

Lens"Photograph

39

[16]

Toronto

Market

58

[17]

Toronto

Market

sketch59

[18]

Unlonvllle,

Ontario

61

[19]

Unlonvllle,

Ontario

sketches62

[20]

CooperAtown

Shop

63

[21]

CooperAtown

Shop

sketches64

[22]

ChokoloAkee

PoAt

0lce

66

[23]

ChokoloAkee

PoAt

O^lce

sketches67

[25]

Toronto

BeacheA

sketch69

[26]

Key

WeAt

HouAe

70

[27]

Key

WeAt

HouAe

sketches71

[27C]

A

Softer

Palm Tree

72

[28]

Key

WeAt

HouAe

II,

unfinished74

My

Thesis

Proposal

spoke ofexploring

"the

use ofthe

photographicimage

as abasis

for

painting,

along

with research andstudy

ofhistoric,

ethic and aesthetic attitudestoward

such use ofthe

photographic image."The

Proposal

also mentioned

"the

classicallinear

image,""metaphorical

reality"and

"highly-detailed

andperspectivally

accurate image" as ele ments ofmy way

of painting.Looking back,

these topics seemto

be

but

fragments

of a more specificissue:

"What

kind

of paintingshave

I

been

making?"That

is

the

question which thisThesis

Report

undertakes to answer.That

questionis

particularly

important

to mebecause

I

approachpainting

for

somewhatdifferent

reasonsthan

do

many

studentsin

this program.Having

an established vocation as ateacher

ofphotography,

painting

has

become

a majoravocation;

I

do

not planto

become

a "professional" painter.I

have

muchsympathy

for

thedeveloping

painters who areforced

to:. . . clamor

for

akilling,

with somerule-breaking

novelty,

before

they

reachtwenty-five.

Otherwise

they

may

neverbe

noticed.They

want to usethe

last

glimmer of avantgarde mystique

to

gain afew

collectorsbefore

everyone sees throughthe

threads onthe

elbow ofthe

tradition ofthe

new.lInstead,

the

process andjoys

ofpainting

areluxurious

endsin

themselves;

they

allow meto

paint asboth

aninquiry

into

and an enhancement ofmy

ownlife.

My

way

ofpainting

has

risenintuitively,

and out of thesensory

pleasures ofusing

the

materials--without conscious

intellectual

or movement-based choices.I

have

therefore

felt

the

needto

think

moreanalytically

aboutpainting,

to

reflectfurther

onpainting

in

an art-historicalsense,

andto

make athat

photography

here

is

in

the

service of painting.The

early

parts ofthis

reporttherefore

presentmy

reflections and rediscoveries on some "isms" ofpainting

which seem to meto

be

relatedto

my

own work andto

the "photographic"qualities of

that

work.A

fresh

look

is

also taken at perspective

andthe

cameraimage,

whichhas

caused me tofind

new excitementin

every

rememberedpainting

from

past arthistory

courses,

andin

the

photographicimage

itself.

Then

the

report reviewsmy

procedure ofusing

photo graphs asthe

basis

for

painting,

together with comments on thepaintings shown

in

theThesis

Exhibit--and a

few

others.Repro

ductions

ofthe

original photographic color slides ofthe

paint ings'subjects are

shown--they served as

"sketches"

for

thepaintings.

Color

reproductions ofthe

paintings areshown,

andthere

is

a speculation onfuture

directions

.NOTES

iGerald

Sykes

,The

perennialAvantgarde

(Englewood

. . .

Throughout

the

nineteenthcentury

there

wererecurring

tendencies

toward

the

oriental andthe

generally

exotic,

toward

the

Christian

and classicalnaive,

andtoward

the

provincial. . . . theirideal

ofthe

primitive,

imbued

withthe

old conception of a returnto

anharmonious

golden day-- ....differs

from

the

ferocious

primitivizing

ofthe

last

thirty

years ...What

is

Goldwater

getting

at?The

doyen

ofprimitiv-ist

criticism explainsthat

strains of primitivismhave

persisted

for

morethan

acentury

but

that

the

nineteenth-century

ethnographicdiscoveries

had

little

to

do

withthe

direction.

The

interest

in

primitiveart,

he

feels,

is

only

one ofthe

recent revivals ofinterest

in

historically-removed art,

suchas

the

eighteenth-century

love

ofChlnolAerle,

oflater

influ

encesfrom Japan

andPersian,

the

mid-east,

and classicalRome

andGreece.

The

nineteenth-century

Sunday

painters--the

"modern

primitives"--had no

knowledge

ofthe

ethnographicdis

coveriesbut

were called primitivesbecause

their

paintingshad

the

samekind

of appeal tothe

advanced artists asdid

the

primitive artifacts.

Picasso,

for

example,

discovered Rousseau

almostsimultaneously

withhis

discovery

ofIvory

Coast

sculp

ture

and archaicIberian

figures.

The

term

"modern

primitive"should

therefore

be

usedcautiously,

urgesGoldwater;

"naive" mightbe

better

for

contemporary

painters.NAIVE

REALISM

A

colleagueasked,

"What

did

youthink

ofJackie

Schuman's

calling

your paintings 'naive'?"Actually

shesaid,

"In

this

painting

. . .there

is

a naivequality

that

basically

is

extremely

sophisticated,"

Research

was calledfor.

The

ambiguity became

alittle

clearer with a comment

by

Stev,

who waswriting

aboutthe

Ameri

can

Primitive

(!)

painterHorace

Pippin:

Unlike

the

famous

mirror,

mirror onthe

wall,

folk

arttoo

oftentells

you what you wantto

hear.

Looking

ata "naive"

painting,

modern criticsdiscern

elements of "sophisticated"abstraction;

. . .It's

too

bad,

because

folk

artdoesn't

deserve

thiskind

ofsloppy

looking. 3

What

atfirst

seemed a condemnation ofSchuman's

remarkis

softened

in

the

concluding

paragraph:. . .

the

trick,

in

looking

at good naiveart,

is

to savorthe

sophistication andthe

naivete together.4

That

turned

out not tobe

entirely

clear,

either,

soGoldwater

had

to

be

consulted.He

calls attention tothe

prevalence

of"evenly

distributed

pattern and . . . contrasts andbalances

of pure andbrilliant

color,

whose enjoymentis

the

basis

of one side ofthe

admirationfor

[naive]

work"^for

both

painter and viewer.

He

points outthat

the characteristic patterns

in

all the naives ' paintings"would

seemto

indicate

that

they

take

pleasurein

the

rhythmic movementsnecessary

for

their

production as well as

in

the

final

visual effect."6As

a resultthe

"exaggeration

of realisticdetail

andin

its

making

rigid allthe

forms

that

it

renders givesits

scenesto

the

sophisticatedeye a symbolic permanence."'

In

thisway

the

naives'painting

is

related tothe

African

sculptures,

whoseformal

qualitiesare

the

cause ofthe

"relative

permanence ofthe

state offeeling

which

it

renders."8Fascinating!

With

these commentsI

begin

toenjoy

the

designation

of"naive"

and

I

alsofind

arelationship

between

twodissimilar

painters whose work

I

have

long

admired:Rousseau

andMorandi.

Rousseau

naively

made picturesfrom his

isolated

andlimited

experience.

Morandi

made anintellectual

choice which wasinfluenced

by

his

understanding

of past painters.The

work ofboth

suggests"permanence

of the state of feeling."Archaism

and primitivism of

the

twentiethcentury

callfor

further

study.The

arthistorian

Haftmann

attributesto

Kandinsky

anin

The

first,

followed

by

Delaunay

andhimself,

is

that

of"the

Greater

Ab

straction";

the

other,

followed,

for

example,

by

the

Neo-Primitive

Henri

Rousseau,

is

that

of"the

Greater

Reality".

The

secondpath,

like

the

first,

leads

beyond

visiblereality

and reveals a newaspect of

it,

whichKandinsky

calls"the

fantastic

in

the

hardest

matter".9

What

atantalizing

idea--to

be

making

representations ofsolidly

and

carefully

defined

things,

allthe

whilehinting

atideas

which

may

notbe

definable

at all.I

feel

comfortable withthat.

But

how

is

it

that

Rousseau,

called retardatalreby

his

contemporaries,

earns suchhigh

standing

from

Kandinsky?

And

how

canmy

painting

have

drawn

nourishmentfrom

Rousseau?

We

shall see.Haftmann

notesthat

modernart,

in

the

work of painterslike

Delaunay

andKandinsky,

had

turned

away

from

"the

familiar

world ofthings",

away

from

the

positivism of nineteenth century

art,

to

searchfor

spiritual valuesby

means of abstraction.But

the

inanimate

object was notwholly

eliminated,

being

perceived as a potential new symbolic experience.

Attention

to

isolated

objects was promptedby

turn-of

-the-centurydiscov

eries of primitive and peasant arts.Their

color andform

inspired

Kandinsky

and othersto

abstraction while onthe

otherhand

Picasso

and others wereimpressed

by

the

magicalimpli

cations ofAfrican

andIberian

figurative

art."The

primitive,

the

daemonic,

the

archaic:behind

them

the

modern mind sensedthe

old magicalunity

between

man andhis

environment.A

yearning

wasborn

to

returnto

this

magical world."In

the

resulting

searchfor

appropriateforms

to

expressthese

feelings

the

Italian

Primitives

were rediscovered:Giotto,

Masaccio,

Uccello,

Piero.

"They

did

not paintthe

thing

in

its

unique,

accidentalcontexts,

but

the

objectiveidea

they

formed

ofit.

They

brought

the

image

ofthe

thing

into

conformity

12

with

their

definition

of it."The

excitement offinding

anal ogiesbetween

archaicpainting

andthe

new anthropologicaldis

ity

presenting

images

of"the

hardest

-of magicalrealism-

brought

outthe

unexpecteddiscovery

that

a number ofcontemporary

painters existed whose worksdemonstrated

just

this

quality:the

non-professional painters--theSunday

painters--of

the

turn

ofthe

century.The

naive realism ofSeraphine

de

Senlis,

ofAndrg

Bauchant

, ofLuis

Vivin,

ofCamille

Bombois,

and

especially

ofHenri

Rousseau,

demonstrated

the

"minute

styleof

the

lay

paintersintent

onthe

cleardefinition

of each13

separate thing."

"Like

the

early

Italian

Primitives,

[the

Neo-Primitive]

brings

the

visibleimage

ofthings

into

conformity

with

his

idea

ofthem.

His

paintingsdo

notmerely

reproducethings,

but

define

them."In

the

sameway,

the

cruel and sometimes -confusingexcesses of

the

photographicimage

canbe

selectively

alteredto

present"things

ofthe

hardest

matter"as a

fantasy

of whatthey

oughtto

be;

to

redefinethem;

orperhaps,

to

show them asI

like

to

think

they

actually

were."The

mentalimage

correctsnature

[which

is

alltoo

redundantly

presentedby

the

camera]

and

becomes

representation of reality."ROUSSEAU

The

naive painteris

known

to

satisfy

his

intent

by

very

systematic procedures.He

generally

considershimself

acraftsman and goes about

his

work withthe

care of a cabinetmaker;

no action painteris

he!

The

way

ofworking

ofHenri

Rousseau

is

typical,

andis

welldescribed

by

Shattuck:

Rousseau's

primitivism andhis

modernismfinally

came

into

focus

mostrevealingly

in

his

method--forhe

had

a method.It

involved

a regular sequence ofprocedure,

andrested,

despite

his

estimate ofhim

self,

far

more on plane composition andinterplay

of color than on conventions of optical representation.Usually

he

began

with a smallrudimentary

version ofhis

subject: a photograph,sketch,

or engraving.The

subjectshe

chose wereformal

and(except

for

the

tropicalscenes,

whichhe

rapidly

madehis

own)

famil

iar.

His

basic

method wasfree

copying,

a techniquethat

allows a painterto

workquietly

in

his

studiohe

outlined a general scheme ofthe

composition andindicated

areas of color.Then,

starting

atthe

top

andworking

towardthe

bottom

"like

pulling

down

a window shade,"he

filled

in

color and

detail.

In

huge

paintingslike

the

tropical

scenes,

he

found

it

preferableto

apply

one color at atime,

. . .Yetin

generalthe

making

ofthe

finished

work was a matter ofsteadily

applied

craftsmanship

during

whichhe

could reckonthe

number ofdays

or weeks requiredto

completethe

task.

We

owehis

unfailing

meticulousness ofdetail

to

anability

to

sustainthe

craftsman'srole

throughout

the

long

labor

oftransferring

onto canvas

the

compleximage

in

his

imagination.

Speed

of executionis

notthe

flavor

ofhis

art.17Rousseau's

decorative

senseis

almost as sure ashis

sense of colorand,

like

it,

servesthe

luxury

effect as well asthe

needfor

order.(The

terms

areRoger

Fry's).

In

both

color andform,

decorative

stylesfall

into

two

general cat egories: repetition and variation. . . .The

for

mertends

toward

simple rhythmical patterns ,like

arow of

trees;

the

latter

tends

toward

whatFocillon

calledthe

"system

of labyrinth"--Arabicdecorative

borders,

baroque

devices,

and old-fashioned stencils.Most

"primitive"art

favors

repetitivedecoration;

Rousseau

employedboth

techniques

.18

Reading

this

was astunning

experience.But

for

afew

minordetails

this

couldbe

adescription

ofhow

I

have

worked onthe

paintings of

the

recent period!In

asurprising

analogy

this

craftsmanlike method wasnot

too

remotefrom

that

ofthe

Italian

Primitives,

whose wallpaintings

involved

simplification of naturein

favor

ofdesired

didactic

and symbolic religious scenes.Their

execution wasusually

guidedby

a cartoon andthe

final

executionleft

to

the

craftsmanship

ofthe

designer's

assistants.White

also remindsus

that

Giotto's

Arena

Chapel

murals wereindeed begun

atthe

top

and were completedin

registerstoward

the

bottom

"like

pulling

down

a window shade."No

actionpainting

there!

M0RANV1

need

to

redefinethe

"world

ofthings"--a

reflection ofthe

need

for

a"greater

reality"--was stimulated

by

the

availability

of works of

the

Italian

Primitives.

To

somedegree

the

patri oticfervors

ofthe

First

War

developed

a new sense ofItallanlta

which madethose

archaic painters even more seemto

be

the

source of a new and vitalphilosophy

of painting.To

the

outsideworld,

archaic realism washeld

to

be

the

only

valid

Italian

contributionto

modern art.At

the

time

ofhis

break

withFuturism,

"Carra

spoke ofGiotto's

'magical

serenity

of form' and of

Uccello's

"brotherly

relation with things'."In

apainting

called"Daughters

of Lot"Carra

"attempted

to

rediscover

Giotto's

greatness on a modern plane, whichhe

iden-20

tified

with Rousseau."Carra

became

philosophicalleader,

the

protagonist of archaic realism andthe

principleItallano

, of a quiet andformal

grandness.Morandi,

a reclusiveBolognese,

had

contacts withthe

Metaphysical

painters,

althoughhe

never "joined"the

group,

preferring

anindividual

direction

andfreedom

from

polemics.He

had

abandoned studiesin

the

local

artacademy

in

1913

to

become

apractising

painter,

. . . procendo

dalla

nativa comprensionedei

grandimaestri

italiani,

fra

cuiil

gravePiero

della

Fran-cesca,

da

lui

forse

considerato pernod'un

linguaggio

pittorico strettamentogeometrico,

idea

precisa nelle venientifasi

della

sua opera.Incontratosi

con . . .Carlo

Carra,

. .and was attracted

to

Pittura

Metafisica

by

his

interest

in

the

Italian

Primitives

whomCarra

extolled.Carra

himself

says ofMorandi

that:. . . above all

he

found

justification

in

his

study

of

the

Renaissance

painters andprimitives,

Giotto,

Piero

della

Francesca,

Masaccio.

His

'exile

in

the

past'

was

the

exile of a man whoproudly

knew

that

he

was capable ofinterpreting

his

owntime,

but

who,

in

avoiding

both

the

adventitious andthe

merely

polemi cal, sought ease and comfortin

the

lucid

geometry

ofArezzo,

Florence

andPadua,

in

the

'sweet

perspective'[Uccello's

words]

thatinduced

the

solitude of poetic meditation.22

Critics

agree thatMorandi

'the

archaic masters.His

emotionalinvolvement

withthe

singleobject

led

to

constructionsin

aGiottesque

pictorialspace,

often as

if

curtains weredrawn

acrossthe

back.

Most

ofthe

paintings--even

the

few

landscapes--weredesigned

to presentthe

objectsfrontally

andin

shallow,

receding

planes.White's

comment

"In

all primitive artsthe

first

stagein

the

representation

ofany

cubic objectis

invariably

to

showonly

a singleside of it"23 explains

Morandi 's

compositionby

way

ofhis

admiration

ofItalian

Primitives.

It

is

seen"throughout

his

art."24There

it

is.

Naives--primitivists--tend

to

present theiremotive objects

frontally,

in

shallowlayered

pictorial space.Usually

there

is

an elaboration of the painted surfaceby

complexpattern and

there

is

a stillness, a sense oftime

suspended.Morandi

adoptedthese

qualitiesfrom

study

ofthe

Italian

Primi

tives.

Rousseau

arrived at themby

naiveintuition.

For

having

seen some of

these

naive and archaic attributesin

my

work,

Jackie's

commentis

gratefully

accepted.NOTES

Robert

J.

Goldwater,

PrlmltlvlAm

In

Modern

Painting

(New York:

Harper

Brothers

Publishers,

1938),

p. xx.Jackie

Schuman,

NewAroom

(Rochester:

Channel

21,

April

27,

1977),

review ofR.I.T.

Graduate

Thesis

Exhibit.

Mark

Stev,

"Pippin's

Folk

Heroes,"NewAweek

(August

22,

1977),

p.59.

4Ibid.,

p.60.

5Goldwater,

p.149.

Goldwater,

p.150.

7Goldwater,

p.124.

oGoldwater,

p.123.

lIbid.

, p.167.

Hlbid.

l2Ibid.

, p.168.

i3Ibid.

, p.172.

l4Ibid.

, p.168.

15Ibid.

, p.173.

l6Roger Shattuck,

The

Banquet

VearA

(Garden

City:

Doubleday

Company,

Inc.,

1961),

p.101.

17Ibid.

, p.103.

!8lbid.

, p.105.

l^Massimo

Carra,

MetaphyAlcal

art(New

York:

Praeger

Publishers,

19

),

p.175.

20lbid.

, p.176.

2lP.

M.

Bardi,

Giorgio

Morandi

(Milan:

Edizione

Del

Milano,

1957)

, p.XII.

22Carra,

p.24.

2

3john

White,

The

Birth

andRebirth

o

Pictorial Space

(Boston:

Boston

Book

andArt

Shop,

1967),

p.26.

Because

ofmy

reliance on photographs as sourcesfor

my

painting,

the

attributes ofphotographs--expecially

asI

choose

to

makethem

for

my

"sketchbook"--have a

strong

influ

ence on

the

painting.One

ofthe

strongest attributes ofthe

camera

is

its

perspectiverendition,

as notedby

Ivins

:Photography,

omitting

the

draughtsman,

produced pictures

in

which . . . mathematical perspective wasinherent.

. . .Today

we areflooded

withPhoto

graphicpictures,

i.

e.,

picturesin

which geometrical perspective

has

been

automatically

incorpo

rated.!

Somehow,

though,

I

find my painting

taking

little

advantage of2

"mathematical

perspective"--that

"Italian

perspective" whichso

meticulously

skewersits

multiplevanishing

points withits

receding

orthogonals.I

preferthe

simple, archaicfrontal

viewpoint

in

whichthe

orthogonals converge and unite out ofsight,

behind

the

central object.I

preferthe

simpletactile-3

muscular shapes of

facades

which are parallelto

the

pictureplane.

From

its

beginnings

photography

has

been

usedto

bypass

the

tedium

ofdraftsmanship,

andit

has

oftenbeen

attackedfor

permitting

this

laziness

in

painters.For

methe

answeris

notquite so simple.

The

camera makes avery

rapid sketch whichdoes

notdelay

travel;

it

provides all ofthe

detail

visibleto

close

scrutiny but

which a traditional sketchdoes

not;

it

allows

free

elimination ofdetails

whendesired but

does

notrequire symthesis

from memory

ofdetails

missing

in

the

originalsketch.

I

feel

comfortable withthose

painters"who

usethe

camera as

something

morethan

atranslation

device

....[and

who]

are aware ofits

shortcomings andgladly

make use ofthem

4

Because

I

find

in my painting

akind

of pleasurablepain which

has

to

do

withthe

viewpointinvariably

chosen,

andwhich

itself

encounters one ofthe

theorems

ofperspective,

it

became

important

to

find

whatis

in

print about perspectivewhich might enlighten me.

Ivins

suggests somedirections

by

stating

that:

. . . physiological optics and perspective are

actually

in many

waysdifferent

from

the

monocularoptics and perspective of

the

geometer andthe

photographic

lens,

andthat

our eyes, when we caninvent

situationsin

whichthey

are notdominated

by "conditioning",

give us returnsthat

frequently

are at variance withthe

constructions ofthe

draw

ing

board

andthe

camera.All

the

world talks about"photographic

distortion"but

withoutrealizing

that

the

"distortion"is

no morein

the photographthan

it

is

in

our mentalhabits

and our ownindividual

mechanisms.

5

As

in

looking

up

a single wordin

the

dictionary,

the

researchleads

to

successivefindings

about perspective which are allrelated

to

an analysis ofmy

painting.As

in

the

dictionary

search,

there are groups ofsynony

mous and

overlapping

and seemingly-synonymousterms

whichdeal

with

perspective,

depending

upon a writer's personal preference.Some

closely

related words whichdeal

primarily

withthe

function

of

the

eye--how

it

sees--are naturalperApectlve,

Euclidean

optlcA and phyAlologlcal optlcA or perApectlve.

The

dominant

naturalistic

discovery

ofthe

Renaissance

wears wordslike

artificial

perApectlve,

geometricperApectlve,

mathematicalperApectlve,

one-pointperApectlve,

monocularperApectlve,

central

perApectlve,

central projectlon

andlinear

perApectlve.A

less-known

Renaissance

conceptis

referred to as Aynthetlc perApectlve,

curvilinear perApectlve(this

is

complicatedby

find

ings

that

the

eyenormally

sees straightlines

ascurves,

asin

Illustration

1)

and naturalperApectlve,

whichis

Leonardo's

contradictory

termfor

the

sameproblem,

whichhe

grappled withinconclusively.

So

muchfor

ambiguity;

I

shalltry

to

keep

the

different

authors'terms

in

contextin

orderto

keep

meaningsVIEWING

DISTANCE

[1]

Curvilinearity

ofRetinal

Image.

When

looked

atirom

the

Indicated

dlAtance,

the

bowed

outerllneA

Aeemto

be

Atralght.

ThlA

Ia

becauAe

the

Image

formed

by

the

the

Apherlcal Aunfiaceofi

the

retina.A

Almllarly

viewed,

wouldbe

perceived aAbe dlfifilcult

to

acceptbecauAe

ol

priorAquareneAA .

Curvilinear

[or

Aynthetlc)

baAed

onthlA

phenomenonbut

rather onthe

lact

that the

turning

ofa

the

head

and eye cauAeAcontlnuouAly

varying

polntAoft

view.eye'A

lenA

{allA

uponnormal

checkerboard,

rounded,

but

thlA

wouldTHAT

INSISTENT SQUARENESS

Why

do

my

paintings seem so angular?So

aggressivly

square?

I

like

it

that

way,

of course, orI

wouldn'tdo

them

that

way.A

building's

facade

Ia

usually

formed

ofninety-degree

angles--as

nearly

so as artisan and materialspermit;

and of course

the

frontal

viewpointdoesn't

allowsoftening

by

the

variety

of angles whichlinear

perspectivebestows.

Moving

around anobject--a building--does

continuously

providevarying

perceptions ofthose

anglesbut,

even whenstanding

quietly

atthe

viewpoint whichI

invariably

select,

the

buildings

themselves

don't

seemto

insist

onthe

foursquare

flavor

to

my

senses.

Why

is

this

so?And why do

the

paintings soinsist?

Is

this

curiosity

about ninety-degree anglesmerely

a personalaberration?

I

can atleast

take

some comfortin

Kainz

' s remarkthat

"the

experiments ofthe

GeAtalt-Tpsychologists

showclearly

that

phenomenally

there

is

no angle of85

degrees

or of95

degrees,

but

that

instead

ofthese

there

are right anglesthat

aretoo

small or

too

large."White

takes

adifferent

direction

whenhe

statesthat

"it

seemsto

be

establishedthat

extensive use of straightlines

gives a cold effect to a work of art, and

that

a certainpsycho-7

logical

discomfort

is

involved,

No

matter;

my

curiosity

leads

rightinto

what othershave

observed or concluded aboutperceptions of visual

space,

andto

some speculations ofmy

own.How

far

back

shall welook?

TO

THE

BEGINNINGS

Homo

AaplenAhas

been

making

representationalimages

for

somethirty

thousand years.The

paintings ofAltamira

andLascaux

excitethe

admiration of sophisticated viewerstoday,

even

though

they

do

not seemto

showany

concernfor

that

representation of space called "perspective."

Did

paleolithic painters place their

figures

in

apurely

conceptualspace,

one notneeding

perspectivalrepresentation,

onedealing

with convenit

that

"the

space conception of primeval artis

one ofthe

one-ness of

the

world;

a world of unbrokeninterrelation,

whereeverything

is

in

association,

wherethe

sacredis

inseparable

Qfrom

the

profane"?Could

it

be

that

the

Renaissance

formu

lations

were at alower

conceptuallevel

than

the

primeval?Giedeon,

in

speculating

onthe

space representation ofprehistoric

painters,

holds

that

the

later

Renaissance

mode ofperspective

drawing

merely

showsthe

appearance ofthings

in

arestricted way:

In

linear

perspective--etymologically

"clearseeing"

-objects are

depicted

upon a plane surfacein

conformity

withthe

way

they

areseen,

without referenceto

their

actual shapes or relations.The

whole picture ordesign

is

calculatedto

be

validfor

one station or observation pointonly

. . .every

elementin

a perspective representation

is

related tothe

unique point of view ofthe

individual

spectator.Nothing

oh

thlA

Aort exlAted

In

prehlAtory

.(Emphasis

mine.)

Although writing in

a volumedevoted

to

Greek

andRen

aissance

art,

Ivins

supportsGiedeon 's

conclusionby

anotherline

of reasoning.He

speaks ofhis

conviction that one set ofhuman

perceptionsdepends

upontactile-muscular

information--the

kind

ofinformation

that

wouldbe

availableby

reaching

outand

touching

objects.Objects

sensedin

full

frontal

or profilepositions would

be

immediately

recognizedbut

those

in

obliquepositions would not so

easily

be

recognized;

"the

shapes ofobjects as

known

by

hand

do

not change with shiftsin

positionas

do

the

shapesknown

by

the

eye."In

contrast,

purely

visual

information,

receivedby

successive glances asin

a motionpicture

film,

provides that"objects

continually

changetheir

shapes as we move around them" and that visual

data

generally

is

of"shifting,

varying,

unbrokencontinuity

of quitedifferent

visual effects."

It

follows

that

to

the

tactile-muscular

senses objects exist almost

independently

and areknown

in

theirmost

identifiable,

most significantaspect,

as arethe

parts ofthe

body

in

ancientEgyptian

art.Even

whenvisually

perceived--out of touch and

reach--"tactile"

objects are recognized

by

their

tactile

attributesbecause

of previous eye-hand associationsThe

heart

ofIvins

'There

is

no sense of contactin

vision,

but

tactile

awareness exists

only

as conscious contact.The

hand,

moving

among

the

things

it

feels,

is

always"here",

and whileit

has

three

dimensional

coordinatesit

has

no point of view and

in

consequence novanishing

point;

the

eye,

having

two

dimensional

coordinates,

has

apoint of view and a

vanishing

point,

andit

sees"there'',

whereit

[the

eye]

is

not.The

resultis

that

visually

things

are notlocated

in

anindepend

ently

existing

space,

but

the

space,

rather,

is

aquality

orrelationship

ofthings

andhaA

noexlAt-ence without

them. 13

(Emphasis

mine.)

Thus

it

wouldbe

reasonableto

concludethat

primevalpainters were

object-oriented,

tactile-mindedthinkers,

concernedwith

the

animalto

eat,

its

significant-profileimage

in

magic ofprocreation,

and withthe

tactile-ly

round sun or moon as a signalof

time

to

gatherfood

or tomigrate;

tactile-muscularinfor

mation

certainly;

time

data

perhaps;

but

notdata

of visual spacereceding

to

avanishing

point.Tactile

images,

overlapping

and

transparent--animals

in

most-significantprofile--are

every

where

in

the

caves.If

square objectshad been

a part of thatworld

they

wouldundoubtedly have

been

shownfrontally

and withright-angled cornerAl

THE

ANCIENTS

The

leap

from

paleolithic art spans various selectedapplications of

isolated

parts ofthe

totaltheory

of perspective;

the

development

of a unifiedtheory

wasdeferred

by

lack

of

need,

intellectual

preference,

lack

ofcuriosity,

orintel

lectual

rigidity.It

seems tobe

agreedthat

the

workings of"natural"

perspective--the

functioning

ofthe

eyeto

relateobjects

in

space and to estimate distances--hasbeen

a properactivity

ofthe

eyefrom

the

arrival ofHomo

AaplenAto

his

present state of

development.

However,

the

needto

make pictures,

andthe

intended

use of thosepictures,

did

not callfor

the

representation ofthe

voldAbetween

objectA untilthe

early

Renaissance,

withthe

full

systemization ofthe

methodoccurring

during

the

rise ofhumanistic

concerns ofthe

high

Renaissance.

real-istic

representations--according

to

their

convictions--of carefully

observed objects and ofbeings

in nature, but

their

way

of

image-making

utilizedonly

alimited

portion of whatthe

natural perspective of

the

eye revealedto

them.

The

manner ofrepresentation

differentiated

socially,

withthe

images

ofthe

divine

rulersbeing

mostrigidly

prescribed;

lesser

beings

wereshown with clear evidence of

understanding

whatthe

eyesees,

figures

overlapping

to

show shallowdepth

andin

partialfore

shortening

to

show athird

dimension.

The

extent ofdeparture

from

prescribed modes showsthat

further

extensionsinto

full

perspective would not

have

been

technically

impossible.

Yet

"the

ancientEgyptians,

andtheir

contemporaries,

never usedlinear

perspectiveto

produce a unified picture of a whole scenegiving

a representationin depth

ofthe

component parts withtheir

apparent size and position."The

Gteeks,

according

toPirenne,

introduced

some partsof

the

total

theory

of perspectiveinto

theirwork,

possibly

ona

purely

empirical way.By

the

middle ofthe

sixthcentury

B.C.

there

were vase paintingsshowing

both

foreshortening

of thefigure

and other perspective effects atthe

sametime.

Unfor

tunately,

noGreek

paintings survive,but

"certain

architectural

views unearthed atPompeii

. . . areprobably based

onearlier

Greek

original paintings, and containthe

representationof parallel

lines

perpendicular tothe

pictureplane,

of whichmany

(but

notall)

converge towards a single point."With

the

knowledge

that

the

Romans

simply

adoptedGreek

forms

in

allthe

arts,

this

seemsto

be

a reasonable conclusion.Ivins

objectsto

crediting

theGreeks

withany

knowledge

of perspective at all.

The

first

step

ofhis

argumentis

that

there

is

no attributable example ofHellenic

painting,

andthat

much of

the

sculptureis

known

only

by

fragments

orby

Roman

copies.

Further,

he

holds

that

what wehave

long

held

up

for

admiration

is

conditionedby

nineteenth-century

archaeologists,

whose

training

was notin

aesthetic values.Among

the

mostcomplete

surviving

examples arethe

vase paintings;

these

are. . .

distinctly

a minor art ofdecoration,

in

general not

too

far

removedfrom manufacturing

crafts manship. . . .[they]

arethe

last

possible word ofstylized,

dandiacal

drawing,

decorative

spacing, andfashionable

arrangementin

two

dimensions

--butbeyond

that

they

do

not go.They

rarely have

morethan

the

mosttenuous

emotionalunity,

andthey

never repre sentthings

as seenrelatively

to each otherin

three-dimensional

space.I7

Then,

turning

to

his

previously

citedtheory

oftactile-muscular

mentality,

Ivins

examineshistorical

Greek

geometry

and points outthat

Euclid

andhis

followers

werelimited

by

tactile

and muscular

intuitions

and weretherefore

unableto

cope withthe

idea

ofinfinity.

"Infinity,

whereverit

is,

asby

defi

nition escapes

handling

and measurement.Intuitionally

it

belongs

in

the

field

of vision."Renaissance

perspectiveneeds

infinity

for

its

vanishing

points,

but

because

Euclid

wasable

to

heel

that

parallels nevermeet,

there

couldbe

no consideration of

infinity,

where parallelsvisibly

do

meet.As

another evidence of theGreek

mental setIvins

callsattention

to

the

meticulously

constructed models ofGreek

monumental sites which exist

in

our museums.Exclusive

concernfor

the

tactile

qualities of objectsis

displayed

by

the

fact

that:. . . each

monument,

statue,

theatre,

temple,

is

placed wherever room canbe

found

for

it,

like

potson an

untidy

shelf,

with nothought

of vistas orapproaches,

and no thoughtthat

one erection couldget

in

the

way

of or makeany

difference

in

another.The

fact

that

these

sites werebuilt

up

overthe

generations on agroup

of sacred placesdoes

notaccount

for

the

helter-skelter

arrangement.As

anexcuse

it

admitsthe

fact.

The

only

thing

that

canaccount

for

that

is

an obliviousness to aninter

related or organized visual order.1"

If

we assumethat,

asWhite

believes,

Pompeiian

fresco

painting

reflectsGreek

perspectivediscoveries,

we must alsoconcur with

his

comment thatthe

variousPompeiian

foreshortening

modes

"illustrate

[only]

the

partialunderstanding

of spatialrealism,

or[alternatively,]

the

limited

interest

in

it,

. . .This

disinterest

in

fundamental

realismcan,

attimes,

descend

into

a pure confusion."We

areleft

withthe

conjecturethat

squareness of structures and

the

way

they

wereactually

Aeenby

the

eye,

andthat

elements of avanishing

axis system ofperspective were

being

examined experimentally.(Illustration

2)

Such

a system would record successive eye-fixations while scanning

andblend

them

together

to

actually

depict

structuresto

the

right andleft

ofthe

viewer asreceding both

laterally

andback

from

the

viewer--on a curved

line.

Verticals

would alsohave

to

be

curved,

asin

Illustration

3,

but

to

avoid confusionin

representing

details

known

(to

the

tactile-muscular

senses)

to

be

square,

straight vertical chords weresubstituted,

asin

Illustration

2,

and straighthorizontal

lines

were represented asstraight chords of

the

curving

line

of recession."Here

thereis

no

confusion,

but

the

curving

composition whichboth

organizesand expresses

in

artisticform

the

everyday

experience of the21

turning

head

andthe

roving

eye."Even

if

we allow this argument on antique

perspective,

the

Pompeiian

Fourth

Style

was putto

an endbefore

its

paintings could serve as abasis

for

any

continuing

experiments todepict

unified space.TWO

KINVS

OF

SPACE

The

humanistic

concerns ofthe

Renaissance

requiredthat

the

voidsbetween

objects--buildings--be

represented,

for

that

was,

afterall,

wherethe

new mantravelled.

Although

the

camera oAcura was not

described

untilthe

mid-sixteenthcentury,

revealing

magical projections ofthe

visibleworld,

painterswere

already

concerned about naturalismin

the twopreceding

centuries.

Two

different

ways ofthinking

evolved,

one concerned with

the

experience of the eye andthe

other with whatwas

to

be

confirmedby

the

cameraOAcura,

in

which aflat

"window

into

space"would

be

usedto

alterthe

sphericaldomain

of

the

eye.As

Ivins

has

stated,

the

cameraway

has

become

the

universal

one;

I

am curious aboutthe

other way.The

conflictbetween

reality

andthe

eye was sensedby

Cimabue

in St.

Peter

Healing

the

Lame

atAssisi.

In

order notK

y

^ >^

V

A

N.

M

N

AL

x>'

/ /

/

7U\

/

s

\ s \ ^

\

\

\LM

[2]

The

Vanishing

Axis

System.

ThlA

Ia

a Acheme poAtulatedby

White

aAthe

empiricalbaAlA

oh

Pompeiian

h^^coeA

.The

AyAtem accountA

hofl

l&ck

oh

parallellty

In

painting;

the

eyeIa

claimedto

have

turned

toward

each Atructureto

give each adlhh<LH-<int

pointoh

view--ahoierunner

oh

Aynthetlc perApectlve.

The

phyAlcalknowledge

oh

Atralght architecturalhormA

waAtaken

careoh

by

uAeoh

Atralght AegmentA aAknown.

The

AyAtemhinted

at a cylindrical AyAtem with a vertical axlAInAtead

oh

& singlevanlAhlng

point.[At

the

leht.)

On

the

rightIa

the

adaptationoh

the

vanlAhlng

axlA AyAtemby

the

Italian

VrlmltlveA.

LlneA

known

to

be

parallelto

the

picture Aurha.ce were retained aA parallel.The

resulting

AenAeoh

Apace,

eApeclally

In

InterlorA

, reAultAIn

a^ee-Ltng

oh

"opening

outtoward

the

[3]

A

Fully

Curvilinear

Perspective

System.

The

conAtructlonoh

the

Image

oh

& rectangular object aA Aeenby

eyehfl0m the

centeroh

the

Aphere on whichIt Ia

projected.Compare

withIllustrations

11

and15.

From the

Aame poAltlonoh

the

eye,

the

rectangular object wouldbe

Imaged

aA rectangularlh

athrough

the

pictureplane,

the

sceneis

constructedfrom

three

separate viewpoints.

The

central structureis

presentedfront-ally

andthe

two

side structures arein

foreshortened

frontal

mode,

which preventsthe

viewerfrom escaping

by

running

the

foreshortened buildings

to

the

decorated

borders

ofthe

panel.The

effectis

that

ofinverted

linear

perspective,

withthe

vanishing

pointin

the

viewer's position.It

is

asif

the

viewer were

to

look

simultaneously

atthe

buildings

from

the

center and

from

the

extreme right andleft

ofthe

scene.It

was a

daring

experiment withthe

"turning

head

andthe

roving

eye."

(Illustrations

4

and5A)

The

early

fourteenth-century

Arena

Chapel

frescoes

by

Giotto

show great concerns with volumes andharmony

between

the

subject and

the

flat

wall whichvisibly

supportsthe

frescoes.

It

was apainterly

concern.One

panel,

The

TeaAt

atCana,

is

held

to

be

"the

first

clear-cut example of[the]

tendency

toapply

to

architecturaldetails

the

rules of natural visionbased

upon

the

turning

of eye andhead

to

look

directly

atthe

various2

3

objects

in

the

field

of vision."The

energy

expendedby

Giotto

and

his

followers,

unlikethe

experiments atPompeii,

remainedclearly

visiblefor

study

anddevelopment.

(Illustration

5B)

Giotto's

studentMaso

di

Banco

followed

thisidea

in

the

frescoes

ofSta.

Croce

atFlorence;

they:. . . seem

to

reveal aconsistent,

and ever moreclearly

expressedtendency

to

makethe

painted sceneconform

to

the

appearance ofthe

real world asboth

head

and eye are turnedto

focus

onits

multifariouscontents. . . .

The

end effectis

ofcompletely

curvilinear

compositions,

painted asif

onthe

surface ofa hemisphere.24

Paralleling

Maso's

curvilinearity

,Ambrogio

Lorenzetti

painted

City

oh

Good

Government

atSiena

andfollowed his

ownempirical experience of

vision,

which wasto

be

in

conflict withthe

invention

of a one-point perspective systemin

the

early

part of

the

fifteenth

century.(Illustration

5C)

Lorenzetti 's

fresco

. . . curves

backwards

from

the

centre,

asif

receding

softly

from

the

observer'sshifting

gaze- . .it

situa-_____ o

b

<?

c s>p>

i

M/

Synthetic Perspective

Artificial Perspective

Figure

ia.

Frontal

c.Foreshortened Frontal

b.

Complex Frontal

d.

Oblique

(Extreme)

e.

Softened Oblique

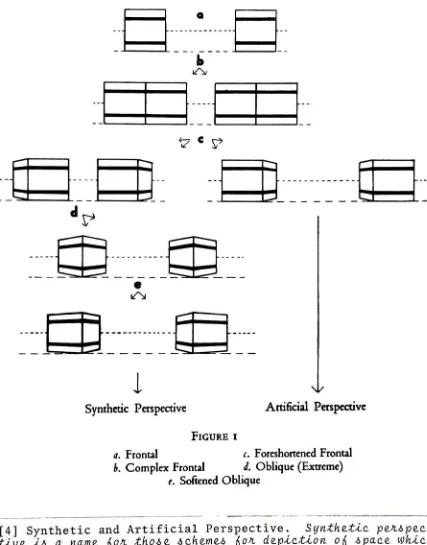

[4]

Synthetic

tlve

Ia

a namedo

notdepend

In

"c"above,

parallelto

th

the

AtructureA alAo parallelAldeA

oh

the

aand

Artificial

Perspective.

Synthetic

perApec-hor thoAe

AchemeAho!t

depletion

oh

Apacewhich

on

the

one-point photographic modeA.For

example,

the

right-hand view AhowAh^^tA

oh

AtructureAe picture plane and

the

nearer,

Inner

vlewAoh

' AldeA.The

Aynthetlc verAlon AhowAthe

h*-ontA

to

the

picture planebut

alAo AhowAthe

outer [image:31.541.48.475.78.623.2]T

T

T

B

T

T

T

\]>

[5A]

Cimabue.

The

Roving

Eye

Ia

taken

to

dramatically

Aepa-ratedvlewpolntA;

the

outer AtructureA, Aeenh,l0m their

har

AldeA,

reAultIn

a AenAeoh

convergence atthe

Apectator.

[5B]

Giotto.

Late

thirteenth- andearly

hu,t-teenth-century

palnterA uAed oblique vlewA

to

Ahow three-dlmenA

tonality;

adepletion

oh

unlhlcd Apace waA notthe

objective,

aothat the

Roving

Eye

waAtaken

to

polntA appropriatehofl

zachAtructure.

[5C]

Abrogio

Lorenzetti.

Turning

the

eyetoward

each Atructure

putA each at adlhherent

angle,

cauAlng

the

Atralght

line

tion,

alwayslooking

outwardsfrom

himself,

the

centre of

this

world.It

is

the

reverse ofthe

fro

zen stare ofthe

fifteenth-century

perspectivein

which

the

composition

is

suckedin

towards

a singlepoint

by

centring

[Ale]

orthogonals.26Uccello,

consideredto

be

one ofthe

inventors

ofthe

one-point

perspective

system,

nevertheless continuedto

strugglewith

the

ideas

putforth

by

his

predecessors,

to

try

to

reconcile visual

truth

to

nature with mathematical perspectivetheory,

The

Flood,

in

Sta.

Maria

Novella

atFlorence,

shows straightlines

as subtlecurves,

withvanishing

pointschanging

asthe

viewer scans

the

picture.He

was notmerely elaborating

ever more complexapplications of

the

theory

of artificial perspective

... .He wasinquiring

into

the

nature andvalidity

ofthe

newmethod,

andweighing

it

againsthis

experience ofthe

natural world.Brunelleschi

himself

[had]

apparently

felt

the

contradiction ofhis

eyes which seemedto

be

entailedin

his

new system.27

ILLUMINATION

The

boldest

experiments withthe

concept of synthetic(curvilinear)

perspective are shownin

the

manuscriptillumi

nations of

Jean

Fouquet

which were made afterhis

Roman

trip

of

1445-1448.

He

wouldhave

had

opportunity

to

seethe

early

Italian

solutionsto

the

questions of synthetic perspectivewhile

he

studiedthe

new one-point systemjust

then

emerging.The

Italian

experimentsturn

outto

have

been

very

cautiouswhen compared with

Fouquet 's

subsequent work.In

his

first

commission afterreturning

to

France,

The

Book

oh

HourA

oh

Etlenne

Chevalier,

Fouquet

boldly

curvedstraight

lines

to

makeforeshortenings

to

both

right andleft.

"Straight

lines

now curveovertly;

sodo

the

braided

tresses

of2 8

the

mat,

as well asthe

beams

ofthe

ceiling.""

"Sometimes,

29

the

dome

ofthe

sky

is

revealed as animmense

orb."(Illus

trations

6,

7)

Later,

having

given more attentionto

the

problem,

Fouquet

illustrated

LeA

GrandeA

ChronlqueA

de

France

andadvo-[6]

The

Annunciation

oh

the

Death

oh

Virgin.

Fouquet,

ca.1449.

cated

in his

theory

ofsynthetic

perspective."30 (Illustra-"tion

8)

In

LeA

AntlqulteA

JudalqueA

Fouquet

exploredthe

convergence of

tall

buildings

when see