P

EDIATRICS

Mar 2003VOL. 111 NO. 3

䡠䡠䡠 䡠䡠䡠 䡠䡠䡠 䡠䡠䡠 䡠䡠

Effectiveness of Pulse Oximetry Screening for Congenital Heart Disease

in Asymptomatic Newborns

Robert I. Koppel, MD*; Charlotte M. Druschel, MD, MPH‡; Tonia Carter, MS‡; Barry E. Goldberg, MD§; Prabhu N. Mehta, MD§; Rohit Talwar, MD§; and Fredrick Z. Bierman, MD*

ABSTRACT. Objective. To determine the sensitivity, specificity, predictive value, and accuracy of a program of pulse oximetry screening of asymptomatic newborns for critical congenital cardiovascular malformation (CCVM).

Methods. Pulse oximetry was performed on

asymp-tomatic newborns in the well-infant nurseries of 2 hos-pitals. Cardiac ultrasound was performed on infants with positive screens (saturation <95% at >24 hours). Data

regarding true and false positives as well as negatives were collected and analyzed.

Results. Oximetry was performed on 11 281

asymp-tomatic newborns, and 3 cases of CCVM were detected (total anomalous pulmonary venous return ⴛ2, truncus arteriosus). During the study interval, there were 9 live births of infants with CCVM from a group of 15 fetuses with CCVM detected by fetal echocardiography. Six in-fants with CCVM were symptomatic before screening. There was 1 false-positive screen. Two infants with neg-ative screens were readmitted (coarctation, hypoplastic left pulmonary artery with aorto-pulmonary collaterals). Other cardiac diagnoses in the database search were non-urgent, including cases of patent foramen ovale, periph-eral pulmonic stenosis, and ventricular septal defect. The prevalence of critical CCVM among all live births was 1 in 564 and among the screened population was 1 in 2256 (sensitivity: 60%; specificity: 99.95%; positive predictive value: 75%; negative predictive value: 99.98%; accuracy: 99.97%).

Conclusions. This screening test is simple, noninva-sive, and inexpensive and can be administered in con-junction with state-mandated screening. The false-nega-tive screen patients had lesions not amenable to detection by oximetry. The sensitivity, specificity, and

predictive value in this population are satisfactory, indi-cating that screening should be applied to larger popu-lations, particularly where lower rates of fetal detection result in increased CCVM prevalence in asymptomatic newborns. Pediatrics 2003;111:451– 455; pulse, oximetry, screening, newborn, heart.

ABBREVIATIONS. CCVM, congenital cardiovascular malforma-tion; CMR, Congenital Malformations Registry.

C

ongenital cardiovascular malformations (CCVMs) are relatively common with a prevalence of 5 to 10 in every 1000 live births.1In New York State,approximately 25% of malformations are CCVMs.2

With improvements in diagnosis and treatment, the outlook for newborns with CCVMs has changed con-siderably, but these malformations still contribute to significant morbidity and mortality in this age group. Children with CCVM are at approximately 12 times higher risk of mortality in the first year of life.3

Several life-threatening CCVMs are not recognized with screening level II obstetrical ultrasound4,5 or

clinically apparent in the early newborn period. Rou-tine neonatal examination fails to detect ⬎50% of infants with CCVM.6One in 10 infants with CCVM

who died in the first year did not have a diagnosis made of the malformation before death, and of those who died in the first week, 25% did not have the diagnosis identified before death.7With the average

length of stay of asymptomatic newborns reduced to 48 hours, many of these infants will already be at home at the time of onset of clinical signs.

Newborn screening is an essential, preventive public health program. For nearly 40 years, newborn screening programs have provided an important public health service by identifying newborns with congenital conditions that could be managed effec-tively with intervention early in life.8Screening

pro-grams have been developed for metabolic, hemato-logic, and endocrine disorders and more recently for

From the *Department of Pediatrics, Schneider Children’s Hospital, New Hyde Park, New York; ‡Department of Health, New York State, Albany, New York; and §Department of Pediatrics, Good Samaritan Hospital, West Islip, New York.

Received for publication Feb 7, 2002; accepted Aug 1, 2002.

Reprint requests to (R.I.K.) Division of Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine, Schnei-der Children’s Hospital, New Hyde Park, NY 11040. E-mail: rkoppel@lij.edu

hearing loss.9 The effectiveness of a screening

pro-gram is dependent on 1) prevalence of the disorder of interest, 2) simple and reliable methods, 3) avail-able treatment, and 4) favoravail-able cost/benefit ratio.10

On the basis of these criteria, CCVM represents a newborn condition that would be ideally suited to a screening program if simple and reliable methods were available.

The 4-chamber view screening performed by ob-stetricians does allow for prenatal detection of many, although not all, affected fetuses.4,5The costs

associ-ated with routine fetal echocardiography would make it impractical as a screening modality. At present, the only method available for screening large numbers of asymptomatic newborns for CCVM is the discharge physical examination, which has been shown to be ineffective.11,12Pulse oximetry has

been suggested as a method to screen newborns in the early neonatal period to detect these lesions and initiate therapy before they become life-threatening. Byrne et al13 reported the detection of desaturation

secondary to hypoplastic left heart syndrome, coarc-tation, and tetralogy of Fallot in a group of asymp-tomatic newborns through the use of simultaneous upper and lower extremity pulse oximetry. Kao et al14 reported similar findings but cautioned that

pulse oximetry may be inadequate as a screen for coarctation and aortic stenosis (Table 1). In view of the results of these preliminary studies, we were interested in extending the work of Byrne et al and Kao et al to determine the sensitivity, specificity, predictive value, and accuracy of a program of pulse oximetry screening of asymptomatic newborns for critical CCVM.

METHODS

Oximetric screening for critical CCVM was performed by ob-taining a single determination of postductal saturation on all asymptomatic newborns (n⫽11 281) in the well-infant nurseries of 2 participating hospitals during the study interval. All new-borns in the nursery at the time of New York State metabolic screening (hospital A) or all newborns who were being discharged from the well-infant nursery (hospital B) and did not manifest cyanosis, tachypnea (respiratory rate:⬎60/min), grunting, flaring, retraction, murmur, active precordium, or diminished pulses un-derwent oximetric screening. Any infant who did manifest any of these clinical findings was transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit for customary evaluation and was not included in the analysis. To ensure universal screening, the timing of the oximetry determination was linked to the state-mandated metabolic screen-ing (⬎24 hours of age) at hospital A (n⫽8642 [76%]). At hospital B (n⫽2639 [24%]), screening was performed immediately before discharge as part of the list of discharge procedures (average

length of stay for vaginal delivery: 56.9 hours; for cesarean section: 103.2 hours). Critical CCVM was defined as a lesion that would likely require surgical correction during the first month of life. All newborns found to have a postductal saturationⱕ95% underwent additional evaluation by echocardiography. Data were collected from May 1998 to November 1999.

Analyses

The number of true and false positives and the predictive value positive of the screening test were determined from data collected at the study sites. However, determining the false negatives and the sensitivity and specificity required follow-up for children who were readmitted for delayed diagnoses of CCVM. The New York State Congenital Malformations Registry (CMR) was used to as-certain these cases.

The CMR is a statewide birth defects registry. State law man-dates reporting by hospitals and physicians of a child who re-ceives a diagnosis of a birth defect before 2 years of age. CMR reports include the narrative description of the defect, and trained registry staff do the coding. The CMR monitors reporting and compares with hospital discharge data to ensure completeness of reporting. Malformation registration using capture-recapture analysis has been estimated to be 87% complete.15We also

sup-plemented our case finding using hospital discharge data and death certificates.

All CCVM cases in the CMR were matched to the birth file to determine the hospital of birth and to generate a list of children who were born at the participating institutions. This resulted in a list of children who passed the screening test but were later found to have CCVM (false-negative rate). From this the sensitivity and specificity were determined. The medical records of CCVM cases that screened negative were reviewed to determine the accuracy of the diagnosis.

Determination of oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry was the standard of care for all pediatric inpatients at our institution. Pulse oximetry was already in routine use in the well-infant nursery for symptomatic infants. The use of pulse oximetry as a routine vital sign was extended to the standard care of all infants in the nursery regardless of their symptoms. Therefore, informed consent was not requested. The New York State Department of Health Institu-tional Review Board approved the review of patients’ medical records by the CMR, and confidentiality of patient’s medical records was ensured.

RESULTS

Oximetric screening was performed on 11 281 asymptomatic newborns during the study interval: 8642 at hospital A and 2639 at hospital B (Table 2). Three cases of CCVM were detected, including 2 patients with total anomalous pulmonary venous return (oxygen saturation by pulse oximeter: 92%, 88%) and 1 patient with truncus arteriosus (oxygen saturation by pulse oximeter: 86%; Table 3). There-fore, 1 in 3760 asymptomatic newborns was found to have a CCVM by oximetric screening before dis-charge. There was no accrued cost as reusable oxime-ter probes were used with oximeoxime-ters already in place in the nurseries. There was 1 false-positive screen. An asymptomatic infant underwent echocardiogra-phy for postductal desaturation and was found to have a structurally normal heart with persistent right to left ductal shunting as a result of delayed transi-tion from the fetal to the neonatal circulatransi-tion. Two screened infants were readmitted (coarctation, hyp-oplastic left pulmonary artery with aorto-pulmonary collaterals). Other cardiac diagnoses in the database search were nonurgent, including cases of patent foramen ovale, peripheral pulmonic stenosis, and ventricular septal defect. The prevalence of all cases of critical CCVM in the total population was 1 in 564, whereas in the screened population it was 1 in 2256.

TABLE 1. CCVM Amenable to Detection by Oximetry Screen-ing

Ductal-dependent anomalies of the transverse aortic arch (ie, coarctation, interrupted aortic arch)

HLHS complex

Pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum D-transposition of the great arteries

Total anomalous pulmonary venous return Tricuspid atresia

Limitations of oximetry screening Coarctation with large VSD Aortic stenosis

Analysis of the screening test’s performance revealed sensitivity of 60%, specificity of 99.95%, positive pre-dictive value of 75%, negative prepre-dictive value of 99.98%, and accuracy of 99.97%.

At hospital A, echocardiography was performed on 798 fetuses with expected dates of confinement occurring during the study interval, yielding a diag-nosis of CCVM in 15 fetuses with 9 of these being delivered (Tables 2 and 3). Echocardiography per-formed on 108 fetuses at hospital B detected no major lesions (Table 2). Six infants became symptomatic before screening, and 3 infants who were readmitted from home were born at other hospitals where screening was not performed (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The discharge physical examination has been shown to be an inadequate screen for CCVM.6,11,12

An asymptomatic newborn may appear pink despite having clinically significant desaturation. With the incidence of critical CCVM being approximately 2.7 per 1000 live births,16we anticipated a higher yield

of CCVM case detection by oximetric screening of asymptomatic newborns. The detection rate at

hos-TABLE 4. New York State Newborn Screening Program An-nual Report, 1998

Disease Diagnosed Cases

Incidence

Phenylketonuria 6 1/43 200 Maple syrup urine disease 2 1/129 596

Homocystinuria 0 0

Galactosemia 8 1/32 399

Biotinidase deficiency 2 1/129 596 Hypothyroidism 228 1/1137

TABLE 2. Comparison of Results of Pulse Oximetry Screening for CCVM at the 2 Participating Sites

Total Hospital A Hospital B Population (fetal diagnosis live birth⫹screened

infants⫹symptomatic)

11 296 8655 2641

Total major CCVM 20 15 5

Fetal diagnosis 9 9 0

Symptomatic before screening 6 4 2

Number screened 11 281 8642 2639

Major CCVM cases in asymptomatic newborns 5 2 3 Prevalence of major CCVM in total population 1/564 1/577 1/528 Prevalence of major CCVM in asymptomatic population 1/2256 1/4321 1/880 Major CCVM detected by screening/number screened 1/3760 1/8642 1/1320

True positive 3 1 2

False positive 1 0 1

True negative 11 275 8640 2635

False negative 2 1 1

Number of fetal echos 906 798 108

Fetal echo/number screened 8% 9% 4%

TABLE 3. List of Patients, Type of CCVM, and Method of Detection

Patient Diagnosis Detection

Hospital A

1 HLHS Fetal echocardiography

2 Pulmonary atresia-VSD Fetal echocardiography

3 Ebstein’s anomaly Fetal echocardiography

4 HLHS Fetal echocardiography

5 Pulmonary stenosis Fetal echocardiography

6 Tetralogy of Fallot Fetal echocardiography

7 HLHS Fetal echocardiography

8 Coarctation, hypoplastic arch Fetal echocardiography

9 Interrupted aortic arch Fetal echocardiography

10 D transposition of the great arteries Cyanosis

11 Ebstein’s anomaly Respiratory distress

12 Transposition of the great arteries Cyanosis

13 Coarctation Tachypnea, murmur

14 Truncus arteriosus Screening (Spo286%).

Hospital B

15 D transposition of the great arteries Cyanosis

16 Pulmonary atresia Cyanosis

17 TAPVR Screening (Spo292%)

18 TAPVR Screening (Spo288%)

Born at hospitals without screening

19 Coarctation CHF, shock

20 HLHS Cyanosis, shock

21 Tetralogy of Fallot Murmur

False-negative screen

22 Coarctation CHF

pital B of 1 in 1320 is close to the predicted incidence of 2.7 in 1000 and is comparable to the incidence of congenital hypothyroidism. Despite the large num-ber of prenatally detected lesions, a detection rate by screening of 1 in 3760 for the 2 sites combined is far greater than the rates for most conditions included in the New York State screening program (Table 4).

Comparing the data for the 2 participating institu-tions reveals the impact of frequently performed fe-tal echocardiography on the yield from screening (Table 2). Our data suggest that in a center where fetal echocardiography is readily accessible, many lesions will be diagnosed prenatally and therefore will not require screening for detection. This phe-nomenon has the effect of decreasing the prevalence of CCVM in the population of asymptomatic infants undergoing oximetric screening. Centers where fetal echocardiography is performed less frequently are likely to demonstrate higher yields from oximetric screening.

It is impossible to know whether the newborns with fetal echocardiographic diagnoses in our series would have been detected by screening or would have become symptomatic before screening. How-ever, the prenatally diagnosed lesions in our series, with the possible exception of the case of coarctation, would have been amenable to oximetric detection (Tables 1 and 3). The 2 false-negative screen patients (coarctation, hypoplastic left pulmonary artery with aorto-pulmonary collaterals) had lesions that may not cause desaturation and therefore represent the limitations of screening for CCVM by oximetry (Ta-ble 1).

A total of 4 echocardiograms were performed on the basis of postductal desaturation at the time of screening of 11 281 asymptomatic infants. Three of these echocardiograms revealed major CCVM in asymptomatic infants. No unnecessary echocardio-grams were performed in the context of this study. Although the fourth echocardiogram did not detect a major CCVM, the infant did have delayed transition from fetal to neonatal circulation with evidence of increased pulmonary artery pressure and right-to-left ductal shunting. This infant remained hospital-ized for observation until the pulmonary hyperten-sion resolved.

Oximetric screening for CCVM seems to satisfy the requirements for a screening test: 1) the prevalence of

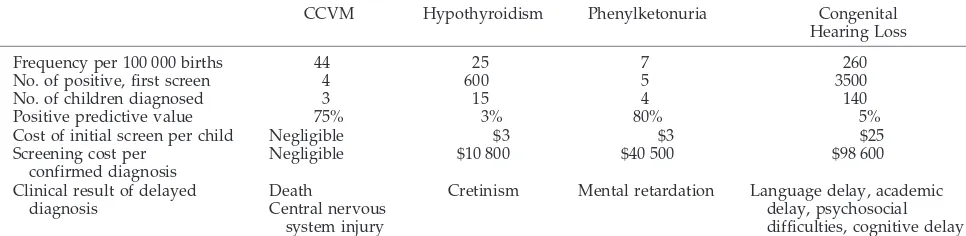

CCVM among asymptomatic newborns is high, par-ticularly in areas with lower rates of fetal echocardi-ography, 2) the technique of oximetric screening is simple and reliable, 3) effective cardiovascular inter-ventions are available, and 4) the cost/benefit ratio in our series was favorable. No costs were incurred for equipment, supplies, or personnel, and 3 asymptom-atic newborns were prevented from going home with undiagnosed CCVM. Oximetric screening for CCVM compares favorably to other newborn screen-ing programs already in place9(Table 5).

The issue of whether detection of critical CCVM by oximetric screening improves the perioperative and long-term outcomes for these infants is beyond the scope of this study. However, studies have shown a favorable impact on outcome with fetal detection of hypoplastic left heart syndrome17 and transposition

of the great arteries18compared with neonatal

detec-tion. These critical lesions are detectable by oximetric screening (Table 1), and, therefore, it is likely that infants with these lesions detected by screening be-fore discharge from the nursery would also have a better outcome than infants readmitted from home. It is important to note that 10% of the postnatally diagnosed cases in the hypoplastic left heart syn-drome study were readmitted from home.17

Pulse oximetry is already in widespread use in newborn nurseries, and normative data regarding saturation during the period of neonatal cardiopul-monary adaptation has been developed.19Oximetry

screening is not intended to serve as a substitute for a careful physical examination. Our screening test, based on a single determination of postductal satu-ration, is noninvasive, cost-effective, and readily co-ordinated with state-mandated screening tests. The sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value in this population are satisfactory, indicating that screening should be applied to larger populations, particularly where lower rates of fetal detection result in in-creased CCVM prevalence in asymptomatic new-borns. Despite its limitations, implementation of oximetry screening will increase the likelihood that newborns with clinically occult CCVM will be iden-tified in a timely manner.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by a cooperative agreement from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

TABLE 5. Comparison of Oximetric Screening for Critical CCVM Versus Screening for Hypothyroidism, Phenylketonuria, and Congenital Hearing Loss

CCVM Hypothyroidism Phenylketonuria Congenital Hearing Loss

Frequency per 100 000 births 44 25 7 260

No. of positive, first screen 4 600 5 3500

No. of children diagnosed 3 15 4 140

Positive predictive value 75% 3% 80% 5%

Cost of initial screen per child Negligible $3 $3 $25 Screening cost per

confirmed diagnosis

Negligible $10 800 $40 500 $98 600

Clinical result of delayed diagnosis

Death

Central nervous system injury

We acknowledge the nursing staff of the newborn nurseries at Long Island Jewish Medical Center and Good Samaritan Hospital for dedicated participation in this study. Oximeters were provided by Ohmeda Medical.

REFERENCES

1. Payne RM, Johnson MC, Grant JW, Strauss AW. Toward a molecular understanding of congenital heart disease.Circulation. 1995;91:494 –504 2. New York State Department of Health.Congenital Malformations Registry Annual Report. Albany, NY: New York State Department of Health; 1997 3. Druschel C, Hughes JP, Olsen C. Mortality among infants with congen-ital malformations in New York State, 1983–1988.Public Health Rep. 1996;111:359 –365

4. Sharland G. Changing impact of fetal diagnosis of congenital heart disease.Arch Dis Child.1997;77:F1–F3

5. Fernandez CO, Ramaciotti C, Martin LB, Twickler DM. The four-chamber view and its sensitivity in detecting congenital heart defects.

Cardiology.1998;90:202–206

6. Wren C, Richmond S, Donaldson L. Presentation of congenital heart disease in infancy: implications for routine examination.Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed.1999;80:F49 –F53

7. Kuehl KS, Loffredo CA, Ferencz C. Failure to diagnose congenital heart disease in infancy.Pediatrics.1999;103:743–747

8. Pass KA, Lane PA, Fernhoff PM, et al. US newborn screening system guidelines II: follow-up of children, diagnosis, management, and eval-uation. Statement of the Council of Regional Networks for Genetic Services (CORN).J Pediatr.2000;137:S1–S45

9. Mehl AL, Thomson V. Newborn hearing screening: the great omission.

Pediatrics.1998;101(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/ full/101/1/e4

10. American Academy of Pediatrics, Newborn Screening Task Force. New-born screening: a blueprint for the future.Pediatrics.2000;106:389 –397 11. Cartlidge PH. Routine discharge examination of babies: is it necessary?

Arch Dis Child.1992;67:1421–1422

12. Abu-Harb M, Wyllie J, Hey E, Richmond S, Wren C. Presentation of obstructive left heart malformations in infancy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed.1994;71:F179 –F183

13. Byrne BJ, Donohue PK, Bawa P, et al. Oxygen saturation as a screening test for critical congenital heart disease.Pediatr Res.1995;37:198A 14. Kao BA, Feit LR, Werner JC. Pulse oximetry as a screen for congenital

heart disease in Newborns.Pediatr Res. 1995;37:216A

15. Honein M, Paulozzi L. Birth defects surveillance: assessing the “gold standard.”Am J Public Health.1999;89:1238 –1240

16. Fyler DC. Report of the New England Regional Infant Cardiac Program.

Pediatrics.1980;65:375

17. Mahle WT, Clancy RR, McGuarn SP, Goin JE, Clark BJ. Impact of prenatal diagnosis on survival and early neurologic morbidity in neo-nates with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Pediatrics. 2001;10: 1277–1282

18. Bonnet D, Coltri A, Butera G, et al. Detection of transposition of the great arteries in fetuses reduces neonatal morbidity and mortality.

Circulation.1999;99:916 –918

19. Levesque BM, Pollack P, Griffin BE, Nielsen HC. Pulse oximetry: what’s normal in the newborn nursery?Pediatr Pulmonol.2000;30:406 – 412

LARGE OFFSPRING SYNDROME

“Most of us regard reproductive cloning—a procedure used to produce an entire new organism from 1 cell of an adult—as a technology riddled with problems. Why should we waste time agonizing about something that is far removed from prac-tical utility, and may forever remain so?

The nature and magnitude of the problems were suggested by the Scottish scientist Ian Wilmut’s initial report, 5 years ago, on the cloning of Dolly the sheep. Dolly represented 1 success among 277 attempts to produce a viable, healthy newborn. Most attempts at cloning other animal species—to date cloning has succeeded with sheep, mice, cattle, goats, cats, and pigs— have not fared much better.

Even the successes come with problems. The placentas of cloned fetuses are routinely 2 or 3 times larger than normal. The offspring are usually larger than normal as well. Several months after birth one group of cloned mice weighed 72% more than mice created through normal reproduction. In many species cloned fetuses must be delivered by cesarean section because of their size. This abnormal-ity, the reasons for which no one understands, is so common that it now has its own name—Large Offspring Syndrome.”

Weinberg RA.Atlantic Monthly. June 2002

Editorial Comment:The great “cloning” debate is going to grow—and grow and grow! Peer review is imperfect, but it’s certainly better than no review, and publication in the press and on television will result in chaos!

DOI: 10.1542/peds.111.3.451

2003;111;451

Pediatrics

Mehta, Rohit Talwar and Fredrick Z. Bierman

Robert I. Koppel, Charlotte M. Druschel, Tonia Carter, Barry E. Goldberg, Prabhu N.

Asymptomatic Newborns

Effectiveness of Pulse Oximetry Screening for Congenital Heart Disease in

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/111/3/451 including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/111/3/451#BIBL This article cites 17 articles, 6 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/cardiology_sub

Cardiology

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

DOI: 10.1542/peds.111.3.451

2003;111;451

Pediatrics

Mehta, Rohit Talwar and Fredrick Z. Bierman

Robert I. Koppel, Charlotte M. Druschel, Tonia Carter, Barry E. Goldberg, Prabhu N.

Asymptomatic Newborns

Effectiveness of Pulse Oximetry Screening for Congenital Heart Disease in

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/111/3/451

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.