Establishment of Conditioned Reinforcement for Reading Content and Effects on Reading Achievement for Early-Elementary Students

Lara M. Gentilini

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019

© 2019 Lara M. Gentilini All rights reserved

ABSTRACT

Establishment of Conditioned Reinforcement for Reading Content and Effects on Reading Achievement for Early-Elementary Students

Lara M. Gentilini

Reading interest is a significant predictor of reading achievement, with effects on both reading comprehension and vocabulary. We measured students’ interest in reading as an estimate of duration of observable reading using whole intervals of silent-reading time. In Experiment 1, we assessed associations among interest in reading (i.e., reinforcement value of reading) and the reading comprehension and vocabulary of 34 second-grade students. There were significant correlations between reading interest and these dependent measures. In Experiment 2, we simultaneously conducted a combined preintervention and postintervention design with multiple probe logic to test the effect of the establishment of a high interest in reading (i.e., conditioned reinforcement for reading) via a collaborative shared reading procedure with a teacher on reading comprehension and vocabulary. This procedure involved periods of reciprocal reading and related collaborative reading activities designed to increase students’ interest in reading. The establishment of a high interest in reading for 7 of the participants resulted in grade-level increases from 0.1 to 2.2 grades on various measures of reading achievement in less than 9 sessions (315 min). In Experiment 3, we implemented a combined small-n experimental-control simultaneous treatment design and a single-case multiple-probe design with multiple-probe logic. We tested and compared the effects of the establishment of conditioned reinforcement for reading, via the collaborative shared reading procedure with a teacher versus a peer, on

participants’ gains in reading comprehension and vocabulary. All participants for whom conditioned reinforcement for reading was established in Experiment 3 (n = 7) demonstrated

gains in reading achievement after a maximum of nine sessions (412 min), with grade-level increases between 0.2 and 2.5 on measures of reading comprehension and 0.3 to 3.1 on measures of vocabulary. Based on a comparison of the dependent variables included in both Experiments 2 and 3, the modified teacher-yoked collaborative shared reading procedure in Experiment 2 resulted in greatest relative average gains in reading achievement for participants who acquired conditioned reinforcement for reading (n = 3). However, the modified collaborative shared reading procedure with a peer required the least amount of teacher mediation and may be more viable for teachers. This trans-disciplinary effort proposes an account of motivation to read as conditioned reinforcement for reading content and its effects on reading achievement, with the educationally-significant goal of establishing reinforcers for continued learning.

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF TABLES ... vi

LIST OF FIGURES ...vii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS... ix

DEDICATION ... xi

CHAPTER I: ESTABLISHMENT OF A HIGH INTEREST IN READING AND EFFECTS ON READING ACHIEVEMENT FOR EARLY-ELEMENTARY STUDENTS ... 1

Abstract ... 1

Introduction ... 2

Experiment 1 ... 7

Method ... 8

Participants ... 8

Measures and Materials ... 8

Procedure ... 10

Interest in Reading ... 10

Reading Achievement ... 12

Interobserver Agreement for Reading Interest ... 12

Results ... 12 Discussion... 13 Measurement Strengths ... 15 Limitations ... 16 Implications ... 17 Experiment 2 ... 17

ii

Method ... 18

Participants ... 18

Design ... 19

Dependent Measures and Procedures ... 19

Collaborative Shared Reading (CSR) Procedure for Increasing Reading Interest ... 20

Step 1: Reciprocal Overt Reading ... 20

Step 2: Vocabulary Task ... 21

Step 3: Silent Reading ... 21

Step 4: Mental-Imagery Task ... 21

Interobserver Agreement ... 23

Results ... 23

Discussion... 25

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research... 26

Implications ... 28

Conclusions and Future Directions ... 28

References ... 30

Appendices ... 50

Appendix A. Data Sheet for Silent-Reading Probe Procedures for Reading Interest ... 50

Appendix B. Vocabulary Worksheet ... 52

iii

CHAPTER II: THE EFFECT OF THE ESTABLISHMENT OF CONDITIONED

REINFORCEMENT FOR READING CONTENT ON SECOND-GRADERS’ READING

ACHIEVEMENT ... 55

Abstract ... 55

Introduction ... 56

Method ... 60

Participants ... 60

Measures and Materials ... 61

Design ... 66

Procedure ... 67

Reinforcement Value of Reading ... 67

Reading Comprehension ... 68

Covert Reading Comprehension ... 69

Comprehension Drawing... 69

Vocabulary ... 69

Vocabulary Knowledge ... 70

Derived-Relational Responding ... 70

Preference Assessment for Teachers Versus Peers ... 70

Collaborative Shared Reading (CSR) Conditioning Procedure ... 70

CSR with a Peer ... 71

Step 1: Reciprocal Overt Reading ... 71

Step 2: Vocabulary Task ... 71

iv

Step 4: Comprehension Task ... 72

CSR with a Teacher ... 74

Interobserver Agreement and Treatment Fidelity ... 74

Results ... 75

Reinforcement Value of Reading ... 76

Reading Achievement ... 77

Progression Through the Intervention ... 79

Preference Assessment ... 79

Discussion ... 79

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research ... 83

Implications ... 87

References ... 89

Appendices ... 111

Appendix A. Data Sheet for Reinforcement Value of Reading Probe Procedures ... 111

Appendix B. Scoring Sheet for Conditioned Seeing and Derived-Relational Responding, Set A ... 113

Appendix C. Scoring Sheet for Conditioned Seeing and Derived-Relational Responding, Set B ... 115

Appendix D. Student Guide for CSR Procedure ... 117

Appendix E. Trade-in Menu for CSR Procedure ... 118

Appendix F. Sample Book Stimuli Used in the CSR Procedure ... 119

v

Appendix H. Sample Vocabulary Worksheet Answer Key ... 121

Appendix I. Comprehension Worksheet ... 122

Appendix J. Sample Intervention Set-up... 124

Appendix K. Checklist Used by Second Observer for Scoring Treatment Fidelity ... 125

CHAPTER III: GENERAL DISCUSSION... 127

Major Findings ... 128

Future Research ... 131

Educational Significance ... 137

Contributions to the Field ... 138

References ... 140

Appendices ... 144

Appendix A. Average-Increase Across Conditions (Table 1) ... 144

vi

LIST OF TABLES

1. Demographic Characteristics of Participants at Onset of Experiment 1 ... 38

2. Correlations for Reading Interest and Reading Comprehension and Vocabulary in Experiment 1... 39

3. Regression Results for ReadingInterest and Predictor Variables in Experiment 1... 40

4. Demographic Characteristics of Participants at Onset of Experiment 2 ... 41

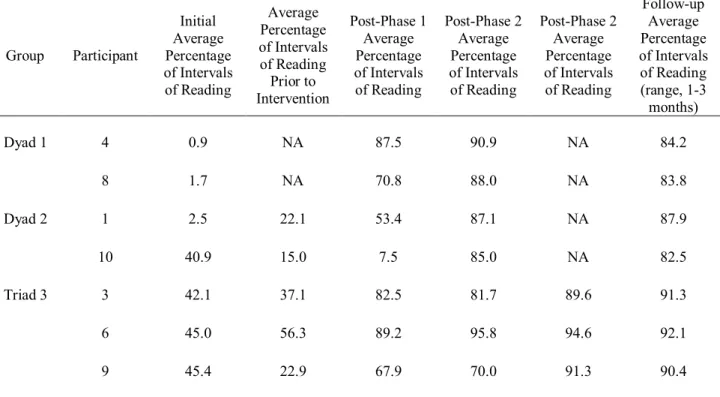

5. Participants’ Average Interest in Reading Per Probe Period in Experiment 2 ... 42

6. Grade-Level Increase in Comprehension and Vocabulary Between Probe Sessions Immediately Prior to and Following Intervention in Experiment 2 ... 43

7. Number and Duration of Intervention Sessions in Each Phase Across Participants in Experiment 2 ... 44

8. Demographic Characteristics of Participants at Onset (Experiment 3) ... 95

9. Participants’ Average Reinforcement Value of Reading Per Probe Period ... 96

10. Average Increase Across Measures of Reading Achievement for Participants in Teacher Versus Peer Condition Between Probe Sessions Immediately Prior to and Following Intervention ... 97

11. Grade-Level Increase in Comprehension and Vocabulary Between Probe Sessions Immediately Prior to and Following Intervention ... 98

12. Percentage Increase in Comprehension Drawing and Derived-Relational Responding Between Probe Sessions Immediately Prior to and Following Intervention ... 99

13. Number and Duration of Intervention Sessions Across Participants ... 100

14. Percentage of Relative Preference in a Stimulus Preference Assessment at Onset of Study ... 101

vii

LIST OF FIGURES

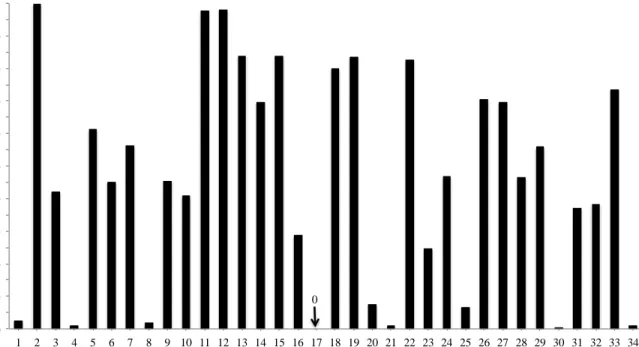

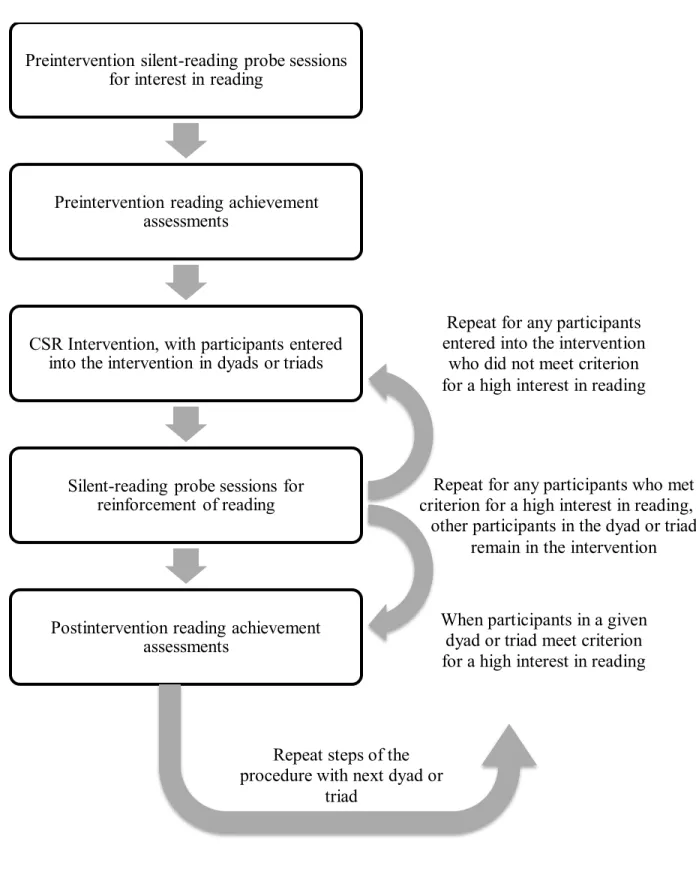

1. Average percentage of 5-s whole intervals of reading across participants in Experiment 1 ... 45 2. Sequence of design in Experiment 2 ... 46 3. Sequence of the teacher-pairing collaborative shared reading (CSR) procedure for establishing a high interest in reading in Experiment 2 ... 47 4. Implementation of the independent variable in Experiment 2, measured by the percentage of 5-s whole intervals of reading within each 10 min probe session ... 48 5. Participants’ grade equivalences on Woodcock-Johnson® Achievement Tests, Fourth Edition (WJ IV) Test 4: Passage Comprehension, Gray Silent Reading Test (GSRT), and WJ IV Test 17: Reading Vocabulary in the preintervention and postintervention probe sessions for Experiment 2... 49 6. Sequence of the design to test the effect of the establishment of conditioned reinforcement for reading via a collaborative shared reading (CSR) intervention with a teacher or peer on

participants’ reading achievement ... 102 7. Sequence of the collaborative shared reading (CSR) intervention conditioning procedure with a peer or teacher for establishing conditioned reinforcement for reading ... 103 8. Implementation of the independent variable, as measured by the percentage of 5-s whole intervals of reading within each 10 min probe session, or reinforcement value of reading ... 104 9. Participants’ grade equivalences on Woodcock-Johnson® Achievement Tests, Fourth Edition (WJ IV) Test 4: Passage Comprehension, Gray Silent Reading Test (GSRT), and WJ IV Test 17: Reading Vocabulary in the preintervention and postintervention probe sessions ... 105 10. Average grade-level increase on Woodcock-Johnson® Tests of Achievement, Fourth Edition (WJ IV) Test 4: Passage Comprehension, Gray Silent Reading Test (GSRT), and WJ IV Test 17:

viii

Reading Vocabulary between probe sessions ... 106 11. Participants’ percentage of accuracy in the comprehension drawing and derived-relational responding preintervention and postintervention probe sessions ... 107 12. Average increase in percentage of accuracy on the comprehension drawing and derived- relational responding tasks between probe sessions ... 108 13. Progression through the intervention for participants in Dyads 1 and 2 ... 109 14. Progression through the intervention for participants in Dyads 3 and 4 ... 110

ix

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To my mentors, students, friends, and family: you have made all of the difference, and to say that this was a group effort would be an understatement.

Dr. Greer, thank you for instilling in me the belief that I am capable and worthy of much more than I ever thought I could accomplish, and for never questioning my quietness. If

“education is what survives when what has been learned has been forgotten,” then you’ve truly given me the most meaningful education of all, and for that I am eternally grateful. Dr. Delgado, I look up to you in every possible sense. Thank you for being the very best role model, and for being there every single step of the way. Thank you to Dr. Wang, Dr. Fienup, Dr. Brassard, Dr. Ross, and Dr. Dudek for your guidance and feedback on my dissertation. Your intelligence and insight have been truly invaluable, and it has been an honor to learn from you.

Kelly Kleinert, thank you for being my life-long mentor, and for always being willing to help me in every way possible. Thank you to all of my mentees, without whom this research would never have been possible. Jen Bie and Alexis Finley, it is an understatement to say that I truly don’t know what I would have done without you, and I am forever indebted to you.

To the staff at Hillcrest School, including Greg Sumski, Carol Hoeg, Paola Hall, and Donna Sjovall: thank you for embodying what it means to put students first. Your patience, understanding, kindness, and mentorship made Hillcrest my absolute favorite place to be. To every student I’ve had the privilege of working with, thank you for teaching me more than I could have ever learned from any book. You’ve given meaning to the last five years, and I genuinely could not be more proud to have been your teacher.

To my cohort, Lenah, Shahad, Becca, Jessica, Ellie, Brittany, and Angela: I don’t know how I got so lucky to have spent the last five years with such a motivated, brilliant, passionate,

x

and collaborative group of people. I am so grateful to have gone through the program with you, and I’ll always be your #1 fan. Ellie, thank you for putting up with all of my questions, and for constantly reminding me that we’ve got this. Brittany and Angela, thanks for being my best buds, and for always believing that I can finish the entire stack of pancakes at Morristown Diner and actually stick to my Lent goals. I’m so grateful to be yoked with you two.

And thank you to my family for loving me unconditionally through every high and low. Nicole, thank you for always reminding me to see the good in things, and for somehow sticking with me from that very first bio test–almonds and all. Justine, thank you for being the most incredible older sister, and for being someone who I’ve genuinely looked up to my entire life. Meghan, thank you for believing in me when I didn’t believe in myself, and for never giving in or giving up (despite all the sass along the way). You have been the light at the end of this very long tunnel, and have proven time and time again that life is worth the wait. To my mom and dad, thank you for always prioritizing happiness above anything else. Cookie, thank you for constantly reminding me that happiness is a conscious choice, and for being my biggest supporter; most influential educator; favorite travel partner; and very, very best friend. You embody what it means to live life to the fullest, and I know without a doubt that nobody will ever have a bigger impact on my life than you. Lorenzo, thank you for every last-minute shopping trip (without a list!), every crazy art project, and every covered book. And most of all, thank you for worrying so I don’t have to, and for sacrificing so much to give me every opportunity in the world. You are all my heroes, and I will spend every day of the rest of my life paying forward the happiness that you’ve given me.

xi DEDICATION

“The sun, with all those planets revolving around it and dependent on it, can still ripen a bunch of grapes as if it had nothing else in the universe to do.” To my entire family, thank you for being my sunshine, and for somehow always putting me first. I love you endlessly.

1 Chapter I

Establishment of a High Interest in Reading and Effects on Reading Achievement for Early-Elementary Students

Abstract

Reading interest is suggested to be a key component of reading achievement, which affects later academic performance. We measured students’ interest in reading as an estimate of duration of observable reading behavior using whole intervals of silent-reading time. We assessed

associations among interest in reading and the reading comprehension and vocabulary of 34 second-grade students. There were significant correlations between reading interest and multiple measures of both reading comprehension and vocabulary. We simultaneously conducted a combined preintervention and postintervention design with multiple probe logic to test the effect of the establishment of a high interest in reading, via a collaborative shared reading intervention with a teacher, on reading comprehension and vocabulary. This procedure involved periods of reciprocal reading and related collaborative reading activities designed to increase students’ interest in reading. The establishment of a high interest in reading for 7 participants resulted in grade-level increases from 0.1 to 2.2 grades on various measures of reading achievement in less than 9 sessions (315 min). The results of this study suggest that it is not enough to learn the structure of reading: rather, one must learn to ‘love to read’ in order to derive meaning from text in his or her development of comprehension and vocabulary.

Keywords: reading achievement, reading comprehension, reading interest, reinforcement value, vocabulary

2

Establishment of a High Interest in Reading and Effects on Reading Achievement for Early-Elementary Students

Early reading abilities are a strong predictor of later reading achievement and overall academic performance. For example, three-fourths of students considered poor readers in third grade are also classified as poor readers in high school, demonstrating higher rates of retention in grade and more behavioral and social problems in successive grades compared to students with higher literacy achievement (Annie E. Casey Foundation; Miles & Stipek, 2006). Alas,only 36% of fourth-grade and 34% of eighth-grade students were considered to be on or above the

Proficient level on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reading assessment, which measures both reading and comprehension skills (U.S. Department of

Education, 2015). Furthermore, there was a decline in the overall average reading score for U.S. fourth-graders between 2011 and 2016, according to the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) report (Warner-Griffin, Liu, Tadler, Herget, & Dalton, 2017). Considering that reading competence is a prerequisite for a wide range of academic skills (Cunningham & Stanovich, 1997; Juel, 1988; Stanovich, 1993), it is critical to determine which factors are associated with literacy development. Extensive research has suggested that reading achievement is comprised of inherent overlap between both “skill and will” (Watkins & Coffey, 2004), such that “motivation is what activates behavior” (Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000, p. 406).

In terms of reading skill, the ability to accurately and fluently decode words and the ability to comprehend spoken language are two of the most significant contributors to reading achievement (Kamhi & Catts, 2012). Other skill-based factors that mediate reading achievement include students’ background knowledge, as well as their inferencing and metacognitive abilities (Kamhi & Catts, 2012). However, the expansion and maintenance of one’s motivation to read is

3

also a critical prerequisite to the derivation of meaning from text, with much of the educational-research literature using the constructs of motivation, preference, and interest interchangeably despite conceptual differences (Conradi, Jang, & McKenna, 2014; Mazzoni, Gambrell, & Korkeamaki, 1999; Petscher, 2010; Schiefele, Schaffner, Möller, & Wigfield, 2012). Several studies have demonstrated a significant relation between intrinsic reading preference, reading amount, and comprehension, when controlling for variables such as reading achievement, background knowledge, and self-efficacy (e.g., Durik, Vida, & Eccles, 2006; Guthrie, Wigfield, Metsala, & Cox, 1999; Stutz, Schaffner, & Schiefele, 2016; Wigfield, Gladstone, & Turci, 2016; Wigfield & Guthrie, 1997a). Moreover, both reading motivation and reading amount have been established as important predictors of reading achievement (e.g., Becker, McElvany, &

Kortenbruck, 2010; De Naeghel, Van Keer, Vansteenkiste, & Rosseel, 2012; Gottfried, Fleming, & Gottfried, 2001; Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000; Taboada, Tonks, Wigfield, & Guthrie, 2009). In addition to demonstrating that reading books is a primary predictor of increases in reading achievement, Anderson, Wilson, and Fielding (1988) reported that teachers significantly

influence how much time children engage in reading outside of school, although it is not enough to simply assign more time for silent reading in the classroom to procure such effects (Bryan, Fawson, & Reutzel, 2003).

The evidence of the relation between reading interest, reading amount, and reading achievement is extensive. However, a major limitation of the existing body of research is that it is heavily rooted in qualitative and descriptive observational methods, often relying on ad hoc

instruments such as retrospective self-report measures (Stutz et al. 2016; Wigfield et al., 2016).

For example, researchers commonly employ attitude scales as measures of reading interest and motivation, including the initial Motivations for Reading Questionnaire (MRQ; Wigfield &

4

Guthrie, 1995, 1997a), Motivation to Read Profile (Gambrell, Palmer, Codling, & Mazzoni, 1996), and Reading Motivation Questionnaire for Elementary Students (Stutz, Schaffner, & Schiefele, 2017). These questionnaires are based on self-assessments of various aspects of reading motivations, with students rating their agreement with items across dimension such as curiosity (e.g., “I like to read about new things”), involvement (e.g., “I enjoy a long, involved story or fiction books), and efficacy (e.g., “I am a good reader) (Wigfield & Guthrie, 1995, 1997a). Such measures differ in both their underlying motivational theories and constructs, lacking a consistent theoretical frame of reference both within and across questionnaires (De Naeghel et al., 2012; Watkins & Coffey, 2004). Another limitation of the existing research on the role of motivation in reading is in its ability to offer consistent definitions of reading motivation that capture the construct’s multidimensionality in a valid and reliable way (Conradi et al., 2014; Petscher, 2010). For example, Murphy and Alexander (2000) reported in their review of

motivation research that researchers explicitly defined only 38% of terms used, highlighting the need for a more precise and objective definition of such motivational constructs.

Whereas one might position ‘motivation,’ ‘preference,’ or ‘interest’ as the variables of interest from a psychological perspective, the theory of verbal-behavior development frames this construct in terms of the reinforcement value of reading (Catania, 1998; Greer & Ross, 2008; Greer & Speckman, 2009). This theory posits that when teaching a child to read, one must consider both the reinforcing value of reading, in addition to the functional features of the text (e.g., how the pictures relate to the corresponding sentences) and the structural organization of the behavior and environment (e.g., the details of the text and pictures) (Catania, 1998; Skinner, 1957). The student’s sustained choice of reading material constitutes a measure of reinforcement value or, in more general terms, his or her interest in reading (Skinner, 1945). We are therefore

5

defining interest in reading as the moment-to-moment selection of the student’s attention to reading material and the degree to which the text maintains this attention, such that this sustained behavior is controlled by the embedded reinforcement of the text’s content (Greer & Ross, 2008; Greer & Speckman, 2009; Skinner, 1957, 1969).

However, neither looking at books nor reading their content are automatically interesting or reinforcing to young children: rather, they become conditioned as reinforcers when observing book stimuli and early reading responses are experienced in close proximity with consequences that are added by others, such as positive social interaction (Vargas, 2013). Researchers often employ respondent or operant conditioning techniques to increase the reinforcement value of developmentally- and academically-functional stimuli by increasing students’ interest in activities or objects that were not previously reinforcing (Greer, 2002). Such procedures comprise stimulus-stimulus pairings, in which a stimulus that does not demonstrate reinforcing characteristics comes to do so through proximate association with a stimulus that is already established as a reinforcer (Pavlov, 1927). For example, several studies have demonstrated the use of contingent social attention to increase students’ interest in academic stimuli that were not initially highly preferred (e.g., Buttigieg, 2015; Lee, 2016; O’Rourke, 2006; Tsai & Greer, 2006). From a psychological perspective, the purpose of such conditioning procedures is to shift from extrinsic motivation, or an emphasis on some external reward or recognition that sustains a given behavior, to intrinsic motivation, or emitting a behavior for the sake of interest (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Deci, Vallerand, Pelletier, & Ryan, 1991). Through pairing with some form of social contact–whether direct reinforcement or the observation of peers–such procedures have been used effectively to condition a range of neutral stimuli as reinforcers (Delgado, Greer, Speckman, & Goswami, 2009).

6

While such pairing procedures are effective in increasing students’ interest in a range of stimuli, there are also collateral effects of conditioning new stimuli as reinforcers, including increased rates of acquisition of related skills (Buttigieg, 2015; Delgado et al., 2009; Keohane, Luke, & Greer, 2008; Tsai & Greer, 2006). In the early stages of learning, building

reinforcement intrinsic to stimuli that attract observing responses such as listening to voices (Greer, Pistoljevic, Cahill, & Du, 2011) or looking at faces (Maffei, Singer-Dudek, & Keohone, 2014) results in children being able to learn faster and in ways they previously could not. Furthermore, conditioned reinforcement for observing books also serves an academic function, considering that choosing to look at books is associated with reading readiness (Morrow, 1983). Children who look at books frequently and freely are more likely to be exposed to a variety of words, pictures, and concepts, with book stimuli selecting out the attention of these ‘voluntary readers’ (Buttigieg, 2015). It has also been demonstrated that the establishment of conditioned reinforcement for book stimuli (e.g., print symbols) via stimulus-stimulus pairing procedures with social reinforcers accelerates the rate of learning of learning to read words for preschool-aged students (Buttigieg, 2015; Tsai & Greer, 2006).

As students progress from the early stages of decoding to reading for aesthetic effects or reading to learn, content becomes the reinforcement needed to sustain the reader’s interest. To extend the work on conditioned reinforcement for looking at books, researchers have designed instructional consequences such that the content of the text selects out the attention of the student, thus enhancing students’ interest in reading. Researchers have previously included collaboration with peers and adults as a critical component of successful interventions for increasing the reading motivation of elementary students, in terms of gaining information and communicating understanding (Cumiskey Moore, 2017; Guthrie, Wigfield, & VonSecker, 2000).

7

In addition, researchers often include cooperative situations and activity-based reading tasks as components of interventions to increase students’ motivation for reading (Nolen & Nicholls, 1994; Pressley, Yokoi, Rankin, Wharton-McDonald, & Mistretta-Hampston, 1997; Turner, 1995). For example, Cumiskey Moore (2017) paired peer social interaction with periods of overt and covert reading to increase the reading interest of fifth-grade students who were above grade-level in reading, utilizing a procedure comprised of opportunities for back-and-forth shared reading between peers. In addition, the procedure involved collaborative activities related to the text for which partners were required to work together to each receive reinforcement (Greer & Ross, 2008; Hamann, Warneken, & Tomasello; 2012; Skinner, 1957). As a result, Cumiskey Moore reported grade-level increases of 0.7 to 3.8 on measures of reading comprehension within a period of a few months with fifth graders, further suggesting that the effects of conditioning procedures extend beyond increasing the reinforcement value of the intended stimuli to gains in related academic skills.

Experiment 1

Given the extensive research on reading motivation, reading amount, and reading comprehension and vocabulary, a goal of the present study was to determine which reading-achievement outcomes are associated with interest in reading amongst second-grade students. Based on previous findings, we hypothesized that there would be significant positive correlations between students’ interest in reading and measures of both reading comprehension and

vocabulary. We utilized the percentage of whole-interval recording of reading during assigned silent-reading periods as a measure of reading interest, with this observational procedure highly correlated with automatically recorded, continuous measurement in a highly-controlled setting

8

of previous methods of measuring reading interest, an experimental investigation of the

correlates of reading interest in the classroom setting can provide a more meaningful account of the factors that casually influence successful acquisition of repertoires underlying reading achievement (Sweet & Snow, 2003; Wigfield et al., 2016).

Method

Participants. We selected 34 second-grade students (52.9% male) with a mean age of 7.8 years (SD = 0.36 years) via a convenience sampling procedure across two cohorts of second-grade students in a Title I K-2 public elementary school (Table 1). The classroom utilizes the empirically-supported Comprehensive Application of Behavior Analysis to Schooling

(CABAS®) Accelerated Independent Learner (AIL) model of education

(www.cabasschools.org), which emphasizes an individualized system of instruction to promote accelerated learning for a wide range of students at varying academic and verbal levels (Greer, 2002; Greer, Keohane, & Healy, 2002; Singer-Dudek, Speckman, & Nuzzolo, 2010). At the start of the study, participants varied in reading level based on their performance on two reading assessments: the Developmental Reading Assessment, Second Edition® (DRA2®) (Pearson Education, 2006) and the i-Ready® K-12 Adaptive Reading Diagnostic (Curriculum Associates, LLC, 2017) (Table 1).

Measures and materials. As a measure of reading interest, the experimenter individually video-recorded participants during 10-min periods of class-wide silent reading. The experimenter set up a recording device (i.e., iPad, iPhone, video camera, or laptop) on each participant’s desk, 1 to 2 ft from the participant. The experimenter positioned the camera in such a way that the participant’s eyes were visible for the entirety of the reading session. Prior to the silent-reading probe sessions, the experimenter provided each participant with two to seven books in

9

the range of his or her reading level. We based the participants’ reading levels on his or her performance on the DRA2® immediately prior to the onset of the study, an assessment with excellent test-retest reliability among early-elementary students (Pearson Education, 2011). In addition, the experimenter covered the books’ pictures to control for the presence of picture stimuli, as the presence of pictures moderates comprehension (Mercorella, 2017). We divided each 10-min silent-reading session into 5-s intervals for the purposes of scoring the video recordings (Appendix A).

We utilized a multi-method approach in our assessment of reading achievement, in order to increase the rigor of our research. Asmeasures of reading comprehension, we included the participants’ scale scores on the i-Ready® K-12 Adaptive Reading Diagnostic domains of literature comprehension and informational text comprehension (Curriculum Associates, LLC, 2017). This adaptive diagnostic test is a computer-based, multiple-choice assessment that presents students with questions at their developmental level based on the accuracy of their previous responses. Within these i-Ready literature comprehension and informational text comprehension subtests, students are presented with various passages with corresponding multiple-choice questions. The i-Ready® K-12 Adaptive Reading Diagnostic is strongly correlated with standardized measures of the Common Core State Standards (Curriculum Associates, LLC, 2017; Educational Research Institute of America, 2016a, 2016b), and demonstrates excellent test-retest reliability to diverse populations of second-grade students (National Center on Response to Intervention, 2019).

As additional measures of covert reading comprehension, we included grade-level equivalence scores from Test 4: Passage Comprehension of the Woodcock-Johnson® Tests of Achievement, Fourth Edition (WJ IV) (Schrank, Mather, & McGrew, 2014) and Gray Silent

10

Reading Tests (GSRT) (Wiederholt & Blalock, 2000). Test 4: Passage Comprehension of the WJ IV assesses students’ understanding of written text, with the majority of text items requiring the student to vocally identify the missing word in sentences or paragraphs of increasing

complexity (e.g., “I like pizza. What do you like to _____?”). The GSRT is also an assessment of students’ covert reading comprehension, requiring students to read paragraphs of increasing difficulty and answer corresponding multiple-choice questions (e.g., “What goes next in this story?” “Which sentence does not fit in the story?”). Previous studies indicate that these

measures have excellent test-retest reliability among second-grade students (McGrew, LaForte, & Schrank, 2014; Wiederholt & Blalock, 2000). The experimenter conducted the WJ IV Test 4: Passage Comprehension in a one-to-one setting and the GSRT in a class-wide setting, utilizing Form A of both measures.

As measures of vocabulary, we included the participants’ scale scores on the i-Ready® K-12 Adaptive Reading Diagnostic vocabulary (Curriculum Associates, LLC, 2017), which assess students’ knowledge of Tier 2 (i.e., high-frequency words used across content areas and

contexts) and Tier 3 (i.e., domain-specific vocabulary) vocabulary words in context. We also measured students’ grade-level performance on Test 17: Reading Vocabulary of the WJ IV, which we conducted in a one-on-one setting (Schrank et al., 2014). This test assesses accuracy in providing synonyms and antonyms to decontextualized words of increasing difficulty. Test-retest reliability for Test 17: Reading Vocabulary of the WJ IV was deemed excellent when calculated using a diverse sample of second-grade students (McGrew et al., 2014).

Procedure.

Interest in reading. The sessions to measure reading interest took place during regularly scheduled periods of class-wide silent reading; however, the experimenter video-recorded each

11

participant separately. Prior to beginning the session, the experimenter instructed the class to read silently at their desks and allowed the participants to select the books they wanted to place on their desks. Throughout the silent-reading period, the experimenter presented behavior-specific approvals for self-management behaviors (e.g., “Great job staying quiet”) across students in the class, at a rate of approximately three approvals per minute.

We defined reading as the participant’s eyes moving across the page of the book from left to right, then returning to the leftmost side of the page after each line. In addition, we considered the participant to be reading if the same pattern of eye movement continued onto the successive page of the book after the participant reached the end of the current page, or if the participant (a) was reading immediately prior to closing a given book, (b) continued to visually attend to the book stimuli while selecting a new book, and (c) selected a new book and began to read (e.g., opening the cover and turning to the first page) within 20 s of closing the previous book (Cumiskey Moore, 2017). The experimenter did not consider the participant to be reading if, at any point within a given interval, he or she stopped engaging in reading, and instead engaged in behaviors such as: (a) uncovering and looking at the covered pictures, (b) interacting with peers, (c) attending to other stimuli, or (d) flipping through the book’s pages without demonstrating eye movements that indicated reading. If the participant engaged in any behavior other than reading during a given 5-s interval, we recorded a minus.

The experimenter recorded participants’ reading using 5-s whole interval recording across 10-min sessions, for a total of 120 intervals per session (Charlesworth & Spiker, 1975). We calculated the participants’ reading interest within each silent-reading session by calculating the percentage of time that each participant engaged in reading across 10 minutes separated into 120 5-s whole intervals. The experimenter video-recorded two silent-reading sessions per

12

participant and conducted additional sessions if there was not a stable level of responding, which we predefined as a difference of more than 25 intervals of reading between two consecutive sessions for a given participant. The experimenter measured reading interest continuously as mean percentage of intervals of reading across sessions (i.e., interest in reading).

Reading achievement. Participants completed the i-Ready® K-12 Adaptive Reading Diagnostic (Curriculum Associates, LLC, 2017) in a class-wide setting over the course of one to three 40-min diagnostic periods across consecutive school days. In WJ IV Test 4: Passage Comprehension, the experimenter instructed the participants to covertly read sentences with a missing word, then respond overtly with the corresponding word (Schrank et al., 2014). In the GSRT, the participants read a series of passages of increasing difficulty and answered related multiple-choice questions (Wiederholt & Blalock, 2000). The i-Ready® vocabulary subtest was part of the same diagnostic assessment as the i-Ready® literature comprehension and

informational text comprehension subtests (Curriculum Associates, LLC, 2017). For the WJ IV Test 17: Reading Vocabulary, the experimenter instructed the participant to read a list of words aloud and provide a synonym or antonym for each word (Schrank et al., 2014).

Interobserver agreement for reading interest. We calculated interobserver agreement (IOA) by dividing the interval-by-interval number of agreements by the total number of

agreements plus disagreements between the experimenter and a second observer, and multiplying that number by 100 to find the percentage. We calculated a mean agreement of 99.0% (range, 92.5-100%) for a random sample of 54.2% of sessions for reading interest.

Results

The average interest in reading across participants was 55.2%, with a range of 0 to 99.6% of 5-s whole intervals of reading across silent-reading probe sessions (Figure 1). Table 2 shows

13

the results of a bivariate Pearson correlation we conducted using SPSS (Version 25; IBM, 2017) to examine the relations between reading interest and the multiple measures of reading

achievement. There was a significant positive correlation between reading interest and all measures of reading comprehension, including WJ IV Test 4: Passage Comprehension (r = .41) and GSRT (r = .44) at the .05 level and i-Ready® literature comprehension (r = .49) and i-Ready® informational text comprehension (r = .61) at the .01 level (Table 2). There was also a significant positive correlation between reading interest and both measures of vocabulary at the .01 level: WJ IV Test 17: Reading Vocabulary (r = .51) and i-Ready® vocabulary (r = .60). All measures of reading comprehension were significantly correlated with all measures of vocabulary (Table 2).

Table 3 also shows the results of a multiple regression analysis we conducted in SPSS

(Version 25; IBM, 2017) to examine the relationship between several predictor variables and percentage of reading interest. Results indicated that multicollinearity was not a concern in these

data. The results of the regression were not significant (F(8, 24) = 0.67, p = 0.71). None of the

individual predictors were significant in the model. Discussion

Data from participants in the current study demonstrate that there are significant

correlations between reading interest and reading comprehension and vocabulary. The results of the current study with second-grade students support Cumiskey Moore’s (2017) findings with fifth graders and suggest a meaningful relation between the extent to which students prefer reading and various measures of reading proficiency. These findings also extend previous work by Stutz et al. (2016), given that we relied on objective behavioral observations instead of retrospective self-report measures to determine “liking of reading.”

14

There are several empirical explanations to support the relation between percentage of intervals engaged in silent reading and reading achievement or, more specifically, to understand why increased reading interest and amount may increase reading comprehension and vocabulary (Pfost, Dörfler, & Artelt, 2013). Considering that students with more highly-developed reading abilities report a higher interest in reading than poorer readers, these students may be more likely to attend to the text during assigned periods of silent reading (Leppänen, Aunola, & Nurmi, 2005; Mol & Bus, 2011). The increased print exposure would then further increase technical reading skills, as well as reading comprehension and vocabulary, thereby further increasing interest in reading (Cunningham, Stanovich, & West, 1994; Kush, Watkins, & Brookhart, 2005; Mol & Bus, 2011; Stanovich, 1986). This hypothesis is further supported by research

demonstrating that students who spend more time reading are more likely to learn new word meanings incidentally from the reading context (the input hypothesis; Krashen, 1989); have better comprehension skills; and are better able to integrate new information into existing schemas (Fletcher, Lyon, Fuchs, & Barnes, 2007; Pfost et al., 2013).

The correlation between reading interest and reading achievement may also be attributable to the expansion of students’ repertoire of background knowledge with increased amount and breath of reading (Anderson et al., 1988; Cipielewski & Stanovich, 1992;

Cunningham & Stanovich, 1991; Stanovich & Cunningham, 1993). Furthermore, the Matthew effect may also serve as an explanation for how increased reading interest drives the

development of reading comprehension and other competencies (Stanovich, 1986; Walberg & Tsai, 1983): “Small initial differences in reading achievement or reading-related skills may well increase over time due to the self-reinforcing mechanisms that drive this developmental pattern” (Pfost et al., 2013; p. 90). This Matthew effect model stresses the mutually dependent and

15

reciprocal causal relation between reading interest and reading achievement, as increased reading supports the development of reading competencies, as well as more efficient reading when reading volume is increased (Pfost et al., 2013).

Based on previous demonstrations of the reciprocal causal relation between reading interest, reading amount, and the acquisition of reading skills, one may expect the relation between these variables to strengthen as students age (Cunningham et al., 1994; Kush et al., 2005; Mol & Bus, 2011; Stanovich, 1986). Therefore, a potential area of future research may entail an analysis of the association between reading interest and reading achievement across the developmental trajectory. In addition, future studies of reading interest should include daily reading amount as a dependent variable in order to determine if students with a high interest in reading are similarly reading more often outside of assigned periods of silent reading.

Measurement Strengths. Our use of multiple tests of reading comprehension can be considering a strength of this study. That is, since tests of this measure assessed the same domain repertories (i.e., covert reading comprehension), “their relationship should capture the stability over time of students’ reading comprehension while not including measure-specific variance that would typically inflate stability estimates of a single instrument administered at two points in time” (Taylor, Frye, & Maruyama, 1990, p. 357). In addition, our inclusion of both WJ IV Test 17: Reading Vocabulary and i-Ready vocabulary as measures of vocabulary provides a more comprehensive account of students’ vocabulary abilities, as these measures separately present vocabulary words in contextualized and decontextualized formats, respectively.

With regard to the silent-reading probe procedures for reading interest, we utilized shorter observation intervals than in the pilot study of the CSR procedure to yield more accurate data (Cumiskey Moore, 2017). We also used whole-interval observation procedures, as opposed

16

to partial-interval recording, in which the observer considers the behavior to be present if it is present at any instance within a given interval. Whole-interval recording underestimates the occurrence of the behavior, thereby providing a more conservative estimate of reading interest (Green, McCoy, Burns, & Smith, 1982). Our silent-reading probe procedures can be considered a reliable measure of reading interest, based on the high degree of agreement amongst independent observers (Kazdin, 1977). In addition, previous research suggests that observations of

participants’ responses utilizing whole-interval recording is highly correlated with automatically recorded continuous responses under laboratory conditions (Greer, 1981; Greer et al., 1973),

further supporting the silent-reading probe procedures as a valid and reliable measure of reading interest. The use of whole-interval observation procedures provides a relatively low-cost and unobtrusive alternative to eye-tracking technology, without compromising the integrity of the data.

Limitations. Although we attempted to control the study environment as much as possible, we note several limitations. First, it is possible that participants’ reading interest was confounded by their reactivity to the presence of the camera on their desks, in spite of our attempts to adequately habituate them to the camera prior to the onset of the study. Another limitation is the restriction of measuring students’ interest in reading exclusively in the

classroom setting during assigned periods of silent reading. Previous studies have found mixed results regarding reading achievement when measuring the relationship between time spent reading at home versus school (Anderson et al., 1988; Greaney, 1980; Heyns, 1978; Taylor et al., 1990; Watkins & Edwards, 1992), and home variables may be different between children in high- and low-interest groups for voluntary reading (Morrow, 1983). Therefore, a limitation of direct observation within the constrained conditions of assigned silent-reading time is that it does

17

not capture reading amount or interest in other contexts (Wigfield & Guthrie, 1997a). Future researchers should measure reading interest in various settings and educational contexts–for example, whether students with a high interest in reading are more likely to select reading as a preferred activity during periods of leisure time. In addition, researchers should include the simultaneous measurement of reading amount, reading interest, and reading achievement, considering that reading amount predicts reading achievement, and that reading amount is also predicted by reading motivation for elementary students (Cox & Guthrie, 2001; Guthrie et al., 1999; Wigfield & Guthrie, 1997b).

Implications. Given that the stimuli that select a student’s attention are considered to be a function of what he or she has learned, education should be focused on the development of teaching procedures to expand students’ repertories of conditioned reinforcers, and in turn shift their interest to more academic behaviors (Greer, 2002). The results of the current study

demonstrate that there is a significant relation between students’ reading interest and reading achievement. However, the question remains as to whether establishing a high interest in reading will lead to successive gains in related repertories. Therefore, the purpose of the second

experiment in the current study was to determine if the procedures utilized in a pilot study on the use of collaborative reading activities would function to increase second-grade students’ interest in reading and, in turn, result in gains in reading achievement (Cumiskey Moore, 2017)..

Experiment 2

In the second experiment, we replicated and extended Cumiskey Moore’s (2017) pilot study conducted with older-elementary students by testing the effect of the establishment of a high interest in reading in second-grade students on the outcome measures examined in

18

the effect of the establishment of a high interest in reading on second-grade students’ reading comprehension and vocabulary? Based on the previous literature, we considered the participant to have a high interest in reading if he or she read for an average of at least 80% of the 5-s whole intervals across silent-reading sessions, such that his or her interest was consistently selected out by the text (Buttigieg, 2015; Cumiskey Moore, 2017; Nuzzolo-Gomez, Leonard, Ortiz, Rivera, & Greer, 2002). We hypothesized that increasing second-grade students’ reading interest to the point of establishing a high interest in reading would result in gains in theses students’ reading achievement.

Given that our study sample was comprised of younger students than the participants in Cumiskey Moore’s study, we employed a collaborative shared reading (CSR) procedure with an adult as opposed to a peer; that is, we paired the reciprocal reading and related activities with attention and collaboration from a teacher, as opposed to a classmate. We postulated that younger students would be reinforced to a greater degree by adults, based on reactivity in the students’ interest in reading in the presence of a teacher as well as prior research on the acquisition of adult attention as a reinforcer for various behaviors in early childhood (Greer & Du, 2015; Schmelzkopf, Greer, Singer-Dudek, & Du, 2017; Tomasello & Bates, 2001). To our knowledge, this is the first study to apply a CSR intervention with a teacher, as opposed to a peer, to establish a high interest in reading among early-elementary students.

Method

Participants. We recruited all participants (n = 7) from Experiment 1 who (a) did not meet the criterion for a high interest in reading, (b) were students in the classroom the first year of the study, and (c) had the lowest interest in reading relative to the other participants in the classroom (Table 4). We included these participants because they had the necessary prerequisite

19

repertoires at the onset of the study to participate, including relevant verbal-developmental milestones (Greer & Ross, 2008).

Design. We conducted a combined preintervention and postintervention single-case design with multiple probe logic to test the effect of the establishment of a high interest in reading via a CSR intervention on reading comprehension and vocabulary for second-grade students. We utilized multiple-probe logic to control for maturation and history by initiating the onset of intervention for selected participants as others remained in baseline or control

conditions. This can be likened to a wait-list control design applied at the level of the case, as opposed to the group. Once the effect of the intervention was present in the first dyad or triad of participants, we entered the next set of participants while the remaining participants continued in the baseline or control condition, therefore utilizing a between participants single-case design (Figure 2). We entered participants into the intervention in dyads or triads to increase the number of students who contact the intervention within the timeframe of the study. There was no change in the participants’ typical instructional environment outside of the context of the intervention.

Dependent measures and procedure. We utilized identical measures as in Experiment 1 for the dependent variables of reading comprehension and vocabulary, with the primary

procedural difference being the experimenters’ utilization of Form B of the GSRT Standard Test Book. In addition, we excluded the i-Ready® comprehension and vocabulary measures; the i-Ready® Reading Diagnostic was a school-wide assessment that could only be administered at mandated periods during the school year, such that we could not collect data on these measures both immediately before and after the intervention. We utilized the data from Experiment 1 as baseline and conducted the same procedures again (a) directly before entering the participants into the intervention and (b) immediately after all participants in the dyad or triad met criterion

20

for a high interest in reading. As a secondary dependent variable, we measured participants’ progress through the intervention partly as a function of the number of sessions required to meet criterion for a given phase; the number of phases required to meet criterion for a high interest in reading; and the duration of each session of the intervention.

Collaborative shared reading (CSR)procedure for increasing reading interest. The experimenter assigned participants to dyads or triads based on their average percentage of reinforcement value of reading in the initial preintervention unconsequated assessment (i.e., probe sessions), entering participants with the lowest reinforcement value of reading into the intervention first, and then assigning the remaining dyads or triads in a stepwise fashion. Prior to each session of the intervention, the teacher presented the participant with a choice of five to eight books; all of the pictures in the books were covered, and the books were within one to two levels of the participant’s reading placement based on the DRA2®. After selecting two to three books (depending on the length of the assigned reading interval), the participant completed all four steps of the CSR procedure with the teacher (Figure 3).

Step 1: Reciprocal overt reading. The participant and teacher first engaged in reciprocal overt reading, such that they rotated reading pages aloud for a given duration of time; that is, one participant read one page aloud, the other participant read the next page aloud, and so forth. Depending on the level of the text, each page had between one to three sentences or paragraphs. The experimenter assigned the duration of the reciprocal reading period based on the average amount of time the participant read silently in the probe sessions immediately prior to entering the intervention, which was dependent on the average number of intervals in which the

participant engaged in observable reading. The experimenter converted the average number of 5-s whole interval5-s of ob5-servable reading to a corre5-sponding number of minute5-s, rounded to the

21

nearest whole minute. If any participant read less than that average amount of time the teacher automatically entered into him or her into the intervention with a reading duration of 2-min.

Step 2: Vocabulary task. Following the reciprocal reading period, the teacher provided each participant with a vocabulary worksheet; the participant was required to write three words from the reciprocal reading period that he or she found interesting or confusing (Appendix B). The teacher also wrote three words from the reading period that he or she thought would be novel for the participant on a separate copy of the vocabulary worksheet. Next, the teacher and participant exchanged worksheets and wrote what they suggested to be the meaning of, and a synonym for, each of the words identified by their partner. After both the participant and teacher completed the vocabulary worksheet, they once again switched their worksheets and discussed each other’s responses–that is, each partner vocally explained why he or she considered each response correct or incorrect. The teacher delivered reinforcement in the form of vocal praise contingent upon the participant’s completion of the task, as opposed to the accuracy of the participant’s responding.

Step 3: Silent reading. The teacher then instructed the participant to read silently for the same duration of time as the reciprocal-reading period, and provided behavior-specific praise (e.g., “I like the way you are keeping your eyes on the book”) at a rate of one to three approvals per minute during the period of silent reading. The teacher did not sit at the same table as the participant during this portion of the intervention.

Step 4: Mental-imagery task. After the designated silent-reading time, the teacher and participant independently completed the mental-imagery worksheet, which required the participant to indicate a specific scene from the pages read during the preceding silent-reading period and then draw a picture of that scene (Appendix C). The teacher also completed a copy of

22

the mental-imagery worksheet. Once the participant and teacher folded their respective

worksheets along the dotted horizontal line (such that the partner would be able to see the picture drawn, but not the written description of the targeted scene), they switched papers and responded to the written antecedent on the back of the worksheet (“I think this drawing is from page

number ________, when the author writes ____________”). The teacher and participant then switched worksheets once again and indicated whether the partner had correctly guessed the targeted scene. If both the teacher and the participant guessed their partners’ scene correctly on the mental-imagery worksheet, the participant earned the previously agreed-upon consequence (e.g., tally towards having lunch with the teacher); if the teacher or participant responded

incorrectly, the partner (i.e., teacher or participant) who guessed incorrectly drew his or her own version of the scene after being told the correct response.

The criterion for each designated duration of reading required that both the teacher and participant correctly identifying the scene drawn by his or her partner. Upon meeting criterion for a session of a given reciprocal and silent reading duration, the teacher increased the duration of reciprocal and silent reading by 2 min. Once the participant had met criterion for three

increases in reading durations (e.g., 2 min, 4 min, 6 min), the experimenter conducted two probe sessions for reading interest, and conducted additional probe sessions until a stable level of responding was reached if the difference in responding between two consecutive probe sessions was greater than 25 intervals.

The experimenter considered the participants to have a high interest in reading if they read for at least 80% of the 5-s whole intervals across sessions in a given probe period. If the participant met criterion for a high interest in reading, the experimenter conducted the

23

did not meet criterion for a high interest in reading, the teacher entered him or her into another phase of the intervention, with the duration of reciprocal and silent reading continuing to increase by intervals of 2 min. The experimenter repeated these procedures after each phase of the intervention.

The experimenter continued to conduct the silent-reading probe procedures for any participants in a given dyad or triad who met criterion for a high interest in reading before the remaining participant(s) in that dyad or triad. If participants who exited the intervention prior to their peers did not maintain a high interest in reading, the teacher entered these participants into the next phase of the intervention. Once all participants in a given dyad or triad met criterion for a high interest in reading, the experimenter conducted the postintervention probe procedures for reading comprehension and vocabulary, while simultaneously conducting a second set of preintervention probe procedures for the next dyad or triad before entering them into the CSR procedure.

Interobserver agreement. Utilizing the same procedures as in Experiment 1, we calculated a mean agreement of 99.2% (range, 92.5-100%) for 55.7% of preintervention probe sessions for reading interest; 99.3% (range, 95.8-100%) for 100% of postintervention probe sessions for reading interest; and 95.8% (range, 86.9-99.2%) for 50.0% of follow-up probe sessions for reading interest.

Results

Table 5 shows changes in participants’ interest in reading as a measure of the

implementation of the independent variable. None of the participants demonstrated the criterion for a high interest in reading (i.e., an average of 80% of 5-s whole intervals across 10-min probe sessions) prior to entering the intervention (Table 5; Figure 4). Only one participant (Participant

24

10) demonstrated a decrease in reading interest after meeting criterion for the first phase of intervention. The majority of participants demonstrated an ascending or stable trend as they progressed through and exited the intervention, as well as in the one- to three-month follow-up probe sessions. All participants demonstrated an average reading interest of at least 80% of 5-s whole intervals in the follow-up probe sessions (Table 5; Figure 4).

Table 6shows grade-level increases across measures of reading achievement between probe sessions immediately prior to and following the CSR intervention. The majority of participants demonstrated increases on WJ IV Test 4: Passage Comprehension (n = 6) and the GSRT (n = 4) (Table 6; Figure 5) following the establishment of a high interest in reading. For the six participants who demonstrated increases on WJ IV Test 4: Passage Comprehension, the range of grade-level increases was 0.1 to 0.8 (Table 7). The range of grade-level increases for the four participants who demonstrated gains on the GSRT was 0.8 to 2.2 (Table 7). Based only on the amount of time that elapsed between the preintervention and postintervention probe periods (approximately 0.2 grade levels for Dyad 1, 0.1 grade levels for Dyad 2, 0.1 grade levels for Triad 3), the majority of participants demonstrated grade-level increases beyond the amount expected on WJ IV Test 4: Passage Comprehension (n = 5) and the GSRT (n = 4); that is, the participants’ change in grade level (the difference between the preintervention and

postintervention grade-level equivalent on these measures) exceeded the amount of time that had passed (in grade levels) between the two probe periods (Table 6). All participants also

demonstrated increases on WJ IV Test 17: Reading Vocabulary, with a range of 0.4 to 0.9 grade-level increases (Table 6; Figure 5). All participants demonstrated grade-grade-level increases beyond the amount expected based solely on elapsed time between the preintervention and

25

Table 7 shows the number and duration of intervention sessions in each phase of the CSR procedure across participants. The majority of participants entered the intervention with a target duration of 2 min, although there was variability in terms of number of phases required to meet criterion for a high interest in reading (Table 7). Participants 3, 4, and 6 required one phase of the intervention; Participants 1, 8, and 10 required two phases of the intervention; and Participant 9 required three phases of the intervention to meet criterion for a high interest in reading. It was necessary for the students to complete at least three sessions to exit a given phase, as criterion was three increases in reading durations. In this study, it took no more than three sessions for the majority of participants to meet criterion for a given phase, with Participant 10 being the only participant to require an additional session to meet criterion in any phase. The range of intervention-session length across Dyad 1, Dyad 2, and Triad 3 was 15.55 to 52.02 min. The range of total session durations per participant was 68:49 to 314:10 min (Table 7).

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that a CSR procedure may be effective in increasing early-elementary students’ interest in reading. Among the participants in this study, seven demonstrated educationally important increases in conditioned reinforcement for reading following the CSR procedure, with grade-level increases from 0.1 to 2.2 with a maximum of 9 intervention sessions totaling 314 min. We identified variable gains across participants between their preintervention and postintervention reading comprehension and vocabulary scores,

supporting the significant reading-achievement increases Cumiskey Moore (2017) reported with fifth-grade students. The relative stability of the participants’ reading interest during baseline assessment increases the internal validity of the results, as it suggests that the intervention was responsible for increases in the participants’ interest in reading. In addition, changes in the

26

participants’ reading comprehension and vocabulary from the immediate preintervention to postintervention assessments imply that the increases in reading achievement were attributable to the establishment of a high interest in reading, since the majority of participants did not

demonstrate an increase in interest in reading from the initial preconditioning probe sessions to the probe sessions immediately prior to entering the intervention. The results of this study therefore suggest that a CSR procedure with a teacher is effective for promoting the academic achievement of second-grade students, with the establishment of a high interest in reading resulting in gains in students’ reading comprehension and vocabulary.

Limitations and suggestions for future research. A limitation of this study is that we did not include a second group of participants paired with peers that would have allowed for the comparison of the CSR procedure with a teacher to Cumiskey Moore’s (2017) procedure

utilizing peers. Although the teacher-pairing CSR procedure was effective in establishing a high interest in reading, the use of peers in the CSR procedure would potentially maximize the number of students who are able to acquire conditioned reinforcement for reading while minimizing the need for teacher assistance within a classroom setting. Moreover, a direct comparison of the two types of conditioning procedures might also elucidate children's shift in preference from adults to peers in terms of efficacy in establishing a high interest in reading.

Another limitation of the current study is the use of Form A of the WJ-IV in both the preintervention and postintervention probe sessions, as the use of multiple forms would have better controlled for changes in the participants’ comprehension and vocabulary as a function of repeated testing. However, the overall stability of the participants’ performance on this measure across preintervention probe sessions within the delayed design suggests that their

27

items. An additional limitation of measurement was the lack of multiple measures of vocabulary, as the experimenter was required to exclude the i-Ready subtest measures to adhere to the school district’s predetermined diagnostic testing periods. Future studies of the CSR procedure should therefore consider including a second measure of vocabulary in order to provide a more complete profile of students’ contextualized and decontextualized vocabulary abilities.

In the current study, participants were permitted to refer back to the text during the mental imagery task before drawing their targeted scene or when guessing their partner’s scene. As a result, it is possible that participants might have guessed correctly without actually reading during the silent-reading period. Future iterations of this design might consider prohibiting reference to determine whether the words will more strongly select out their attention. In terms of the vocabulary task, a limitation of the study was the lack of a direct contingency linking the participants’ correct responding to access to a back-up reinforcer. Within the framework of behavior analysis, the meaning of a word is characterized by its function (e.g., effect on the listener), which is directly related to the effect of using that word as a speaker or responding to that word as a listener (Catania, 1998; Greer & Ross, 2008; Skinner, 1957). Considering that the meaning of a word changes based on reinforcement or punishment from a particular verbal community, the vocabulary component of the conditioning procedure should be consequated if the child is to acquire an expanded vocabulary (Skinner, 1957). The conditioning procedure in the current study failed to embed such contingencies in the vocabulary task, as access to back-up reinforcement was not contingent upon the accuracy of the participant’s responding (Cumiskey Moore, 2017). Therefore, a modified procedure in which the percentage of correct responding determines the reinforcement received may be more effective in promoting vocabulary

28

Implications. The purpose of education in the context of the application of behavior analysis to schooling is for students to come under new environmental control, so that stimuli that did not previously affect their behavior are now controlled by the causes of the behavior and its consequence (Greer, 1983, 2002). From this disciplinary perspective, expert teaching must include arranging instructional consequences such that the reading and comprehension of text select out the attention of the student, thus making reading reinforcing in and of itself (Vargas, 2013). Based on the results of the current experiment, the teacher-pairing CSR procedure adapted from Cumiskey Moore (2017) can be considered a systematic method for establishing a high interest in reading for the sample of second-grade students, with the acquisition of this intrinsic reinforcer promoting successive gains in a variety of advanced reading repertories as students’ covert reading comes under stimulus control.

Conclusions and Future Directions

The results of this study suggest that there is educational significance to establishing a high interest in reading via a CSR procedure with a teacher. Furthermore, the majority of participants who engaged in the intervention demonstrated increases in reading comprehension and vocabulary as a function of the establishment of a high interest in reading, with significant relations between reading interest and these measures of reading achievement. Although the CSR procedure with a teacher was effective in establishing a high interest in reading, the question remains as to whether a peer CSR procedure could be utilized with students in early elementary grades, which may significantly decrease average time required to enact the intervention

(Cumiskey Moore 2017).

A study comparing a CSR procedure with a teacher versus a peer could also provide insight into whether children are more reinforced by adults or peers, as well as at what age