Cite as: Cosh S, Zentner N, Ay E, Loos S, Slade M, Maj Mario, Salzano A, Berecz R, Glaub T, Munk-Jorgensen P, Krogsgaard Bording M, Rössler W, Kawohl W, Puschner B, CEDAR study groupClinical decision making and mental health service use in people with severe mental illness across Europe, Psychiatric Services, in press.

Running head: Clinical decision making and service use in severe mental illness

Title: Clinical decision making and mental health service use in people with severe mental illness across Europe

Disclosures and acknowledgments.

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

The CEDAR study is funded by a grant from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7-HEALTH: Improving clinical decision making; Reference 223290).

Word count. 2 967

Abstract

Objective: This study aims to explore relationships between preferred and experienced clinical decision making with service use, and associated costs, by people with severe mental illness.

Methods: Prospective observational study of mental healthcare in six European countries: Germany, UK, Italy Hungary, Denmark and Switzerland. Patients (N = 588) and treating clinicians (N = 213) reported preferred and experienced decision making at baseline using the Clinical Decision Making Style Scale (CDMS) and the Clinical Decision Involvement and Satisfaction Scale (CDIS). Retrospective service use was assessed with the Client Socio-Demographic and Service Receipt Inventory (CSSRI-EU) at baseline and 12-month follow-up. Negative binomial regression analyses examined the effects of CDMS and CDIS on service use and inpatient costs at baseline and multilevel models examined these relationships over time.

Results: At baseline, staff and patient preferences for active decision making and low patient satisfaction with experienced decisions were associated with longer hospital admissions and higher costs. Patient preferences for active decision making predicted increases in hospital admissions (b= .236,p=.043) over 12 months and cost increases were predicted by low patient satisfaction (b= 4803, p=.005). Decision making was unrelated to medication, outpatient, or community service use.

Conclusions: Decision making is related to inpatient service use and associated costs by people with severe mental illness. A preference for shared decision making may reduce healthcare costs via a reduction in inpatient admissions. Patient satisfaction with decisions is a crucial predictor of healthcare costs; therefore, clinicians should maximize patient satisfaction with decision making.

Introduction

There is widespread agreement that shared, rather than passive, clinical decision making between patients and staff is an ethical obligation (1–3). A collaborative process of decision making contributes to high-quality, patient-centered healthcare (4), with some evidence indicating that shared decision making might have positive effects on treatment outcomes (1,5,6). There is also growing evidence suggesting that, in medical settings, shared decision making may be associated with cost-effectiveness (7), by reducing hospital admissions and other associated medical costs (8).

Although the extant body of literature exploring decision making has largely focused on physical health conditions, decision making is a growing area of interest in psychiatric settings, especially in the treatment of severe mental illness (9–11) with psychiatric patients shown to be capable of (3) and expressing a preference for shared decision making (12–14,1,15). However it remains largely unknown if a preference for or experiences of shared decision making impacts upon service use. It has been suggested that higher involvement of mental health patients in decision making might increase their engagement with services (16), although empirical evidence remains equivocal (1). Likewise, some evidence indicates that satisfaction with decision making has a positive relationship with medication adherence (17), yet other studies have found no such relationship (18). Although there is limited evidence that shared decision making may reduce physical healthcare costs through the reduction of utilizing ineffective or undesirable treatments (19), whether such cost-effectiveness is seen in mental health care remains unknown.

involvement in decision making impact service use? d) Does satisfaction with experienced clinical decisions impact service use?

Method

Design

The study was undertaken as part of the European multicenter study, “Clinical decision making and outcome in routine care for people with severe mental illness” (CEDAR, ISRCTN75841675) (21); a prospective observational study of routine psychiatric care. Patients and staff were recruited from outpatient/community mental health services in six European countries (Germany, UK, Italy, Hungary, Denmark, and Switzerland) between November 2009 and December 2010. Ethical approval was obtained from all participating centers. We used CDM data collected at baseline and service use data that were collected at baseline and 12-month follow up.

Participants

Participants who presented with any psychiatric diagnosis - established by case notes or staff communication, based on SCID criteria (22,23) - were recruited from six European centers. Inclusion criteria were (a) aged 18-60, (b) presence of severe mental illness (Threshold Assessment Grid (24) ≥ 5 points and illness duration ≥ 2 year), (c) expected

contact with mental health services for one year, (d) sufficient language proficiency, and (e) capacity to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria were (a) main diagnosis of learning disability, dementia, substance misuse or organic brain disorder, (b) severe cognitive

Measures

Client Sociodemographic and Service Use Inventory (CSSRI-EU).The CSSRI-EU (25) provides self-report information in five areas: (a) sociodemographic data including ethnicity and education level, (b) living situation, (c) employment and income, (d) service receipt such as inpatient and outpatient hospital services, primary and secondary community care contacts, and (e) medication use. For pragmatic reasons, the data on medication was assessed using a shortened version of the CSSRI (Paul McCrone, personal communication), with patients being asked to indicate type

(psychotropic or non-psychotropic) and number of medications (while the original version also asks for brand name and dose). Community and outpatient services for the prior three months, and number of medications used in the previous one month, were collected. Number and duration of inpatient stays was collected for the previous 12 months. Total costs of inpatient days were calculated by allocating unit costs based on average costs per day of inpatient stays in each participating center during the observation period.

Clinical Decision Making Involvement and Satisfaction Scale (CDIS)(26).This instrument measures involvement and satisfaction with a recently experienced clinical

decision, as rated by both patient and staff. The Involvement (CDIS-INV) subscale is assessed through a single item rating the extent to which the decision was shared, passive or actively made by the patient (rated on a 5-point scale). The Satisfaction (CDIS-SAT) subscale is assessed by level of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale with six items regarding a) being informed, b) making the best decision, c) consistency with personal values, d) expectation of implementing the decision, e) whether this was the best decision to make, and f) overall satisfaction. The satisfaction score is then classified into three categories: high, moderate and low. CEDAR measures and scoring information can be downloaded at

www.cedar-net.eu/instruments.

Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows 23.0. Comparisons of service use, as assessed by the CSSRI-EU, at baseline and follow-up were conducted using non-parametric paired Wilcoxon rank tests, with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple analyses. Costs of inpatient admissions at baseline and follow-up were assessed via pairedt-tests. Predictors of baseline service use were assessed via negative binomial regression analyses, entering all baseline staff-rated and patient-rated subscales of the CDMS and CDIS as predictors, after controlling for age, gender, marital status, study site, diagnosis and duration of illness. To assess changes in service use over time, multilevel models were used with a random slope and intercept; controlling for the same covariates.

Results

the average duration of illness was 12.5 years (SD = 9.3). Each participant had an allocated staff member. Paired data for the 588 patients were obtained from staff members (N = 213); with some staff members providing data for multiple patients. Staff members had a mean age of 45.9 years (SD = 10.6) and 62% were female (n = 127). Of those participating, 37% were psychiatrists (n = 75), 9% psychologists (n = 19), 5% social workers (n = 11), whilst 49% were from another profession within mental health services (n = 100). On average, staff had worked in mental health for 15.0 years (SD = 9.7).

At baseline, the majority of both patients and staff expressed a preference on the CDMS-PD for shared (71%, 54% respectively) rather than active (8%, 16%) or passive (22%, 30%) decision making. The majority of patients reported a preference on the CDMS-IN for receiving high levels of information regarding decisions, whereas the majority of staff preferred patients to receive a moderate amount (high 61%, 35%; mod 35%, 57%; low 4%, 8%). When asked at baseline about the most recently experienced clinical decision on the CDIS-INV, nearly half of all patients and staff reported that the decision had been shared (50%, 47%; passive 27%, 23%; active 24%, 30%). The majority of staff and patients reported being moderately or highly satisfied with the decision on the CDIS-SAT (high 52%, 45%; mod 43%, 51%; low 6%, 4%).

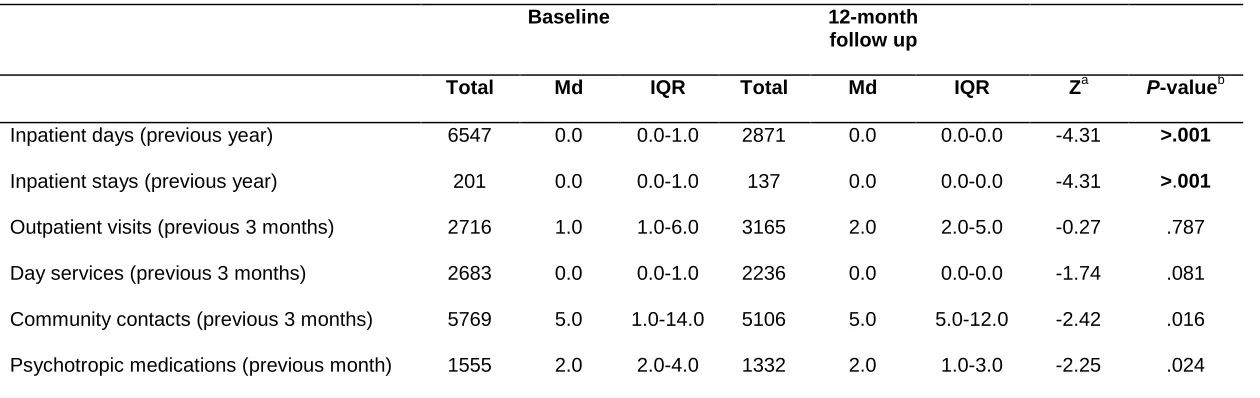

Community contacts and day services were the most commonly used services at both

baseline and follow-up, with a total of 201 inpatient admissions across the sample at baseline and 137 by follow-up (see Table 1). Comparison of self-reported service use showed that number and length of inpatient stays significantly decreased between baseline and follow-up. Likewise, total costs of

inpatient admissions significantly decreased from€2 512 330 at baseline to€807 803 at follow up (t= 3.82, df =519,p>.001). No significant changes were observed for the number of outpatient, day service and community contacts, nor for number of medications prescribed.

##Table 1 about here##

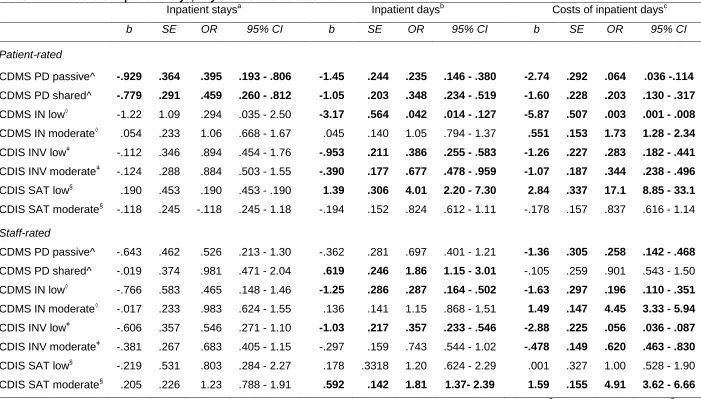

Relationship between decision-making and baseline service use

At baseline, a patient-rated preference on the CDMS-PD for an active style was associated with a higher number of inpatient stays than preferences for passive of shared style (see Table 2).

The duration and costs of such inpatient admissions were significantly predicted by all subscales, both staff- and patient-rated. Patient-rated CDMS preferences for passive or shared CDM style were associated with shorter admissions than preferences for active CDM style and, relatedly, with lower costs compared with preferences for active CDM. On the staff-rated CDMS-PD, a preference for shared CDM style predicted slightly longer admissions, and preferences for a passive style were related to decreased costs. A preference for low levels of information provision on the CDMS-IN (both staff- and patient-rated) predicted shorter

admissions and lower costs than high CDMS-IN. Similarly, both staff- and patient-reported passive involvement in a recent decision on the CDIS-INV predicted fewer days of inpatient admissions than active involvement, and passive and shared CDIS-INV predicted lower costs. Patient-rated low satisfaction on the CDIS-SAT predicted an increased number of admission days and increased costs, whereas a higher number of days and costs were associated with moderate staff-rated satisfaction. The number of outpatient contacts, day services, community contacts, and prescribed medications were not associated with the CDMS or CDIS subscales.

Relationship between decision-making and service use over time

Significant changes in service use were further examined to identify predictors thereof. Number of inpatient admissions was significantly predicted by both patient- and staff-rated CDMS-PD. An increase in the number of stays over time was predicted by patient preference for active decision making (b= .236,t= 2.03, df= 353,p=.043) and a staff preference for shared decision making (b= .181,t= 2.21, df= 353,p=.028). A longer length of inpatient stay was predicted by staff-rated preference for shared decision making compared with a patient preference for a passive style (b= 5.49,t= 2.17, df= 706,p=.030). The change in costs over one year was predicted by the patient-rated CDIS-SAT, with low satisfaction associated with an increase in costs (b= 4803,t= 2.83, df =752,p =.005).

This study contributes to the limited exploration of clinical decision making and its association with mental health service use amongst people with SMI. Decision making preferences and

experiences were associated with number and duration of inpatient admissions and associated costs, both at baseline and with changes over 12-months. Measures of decision making were, however, unrelated to use of medications, and community, day and outpatient services.

Consistent with a growing body of evidence suggesting that, in medical settings, decision making style may be associated with cost-effectiveness (7,8), the present findings also suggest that aspects of decision making are related to service use and costs. Specifically, both preferences for and experiences of passive and shared, as opposed to active, decision making were associated with reduced hospital admissions and costs. Although reduced costs do not equate to cost-effectiveness, such findings are in line with the observations from physical health settings (8) that shared decision making might improve cost-effectiveness, possibly via improved treatment and thus a reduction in the need for hospital admissions (4,7,8). This finding may also reflect shared factors that influence both decision making and treatment outcomes. Those who are less unwell are more likely to express a preference for shared decision making (1, 14) and, concomitantly, are less likely to have inpatient admissions, especially lengthy ones. Additionally, it has previously been reported that patients’ belief of their own decisional capacity influences CDM preferences (31). Thus, preferences for participation in decision making and level of involvement in decisions may be a marker for other factors such as insight, understanding about the illness, and illness severity, which are related to inpatient stays and costs. Our results showed that those preferring and experiencing active CDM had more admissions, thus active, as opposed to passive or shared CDM may be a marker for those who are less well. The extent to which the relationship between decision making and admission costs is mediated by insight and clinical presentation would be a beneficial avenue for future research. More rigorously designed studies are needed to ascertain if decision making has a causal association with reducing admissions and costs.

independently drives the association with costs and admissions, or whether dissatisfaction is associated with poorer wellbeing and greater illness severity and therefore higher costs remains unclear. Although evidence that decision making interventions improve satisfaction is currently limited, this finding provides further support that the ongoing development of

strategies to maximize patient satisfaction with CDM experiences (e.g., 33,34) may be beneficial in reducing admissions. Relatedly, the extent to which differential preferences of patient and treating clinician impact upon experienced CDM, especially patient satisfaction, would be a value avenue for future exploration. Given the relationship between satisfaction and service use, staff awareness of patient preferences and expectations would likely be valuable to assist in enhancing patient satisfaction.

The study lends support for the assertion that there is no relationship between preferred and experienced CDM and medication use in outpatient mental health settings (18), contrasting previous findings showing satisfaction is related to medication adherence (17). Additionally, despite previous evidence suggesting that involvement in decision making might increase engagement with community care services (16), in the present study, the use of outpatient and community services was unrelated to CDM preferences and experiences. Although engagement was not directly studied, outpatient service use may serve as a proxy indicator of engagement. Thus our results suggest that decision making, at least in those with SMI, may be largely unrelated to engagement with outpatient services. Such a finding may reflect that other factors contribute more to engagement with services, or may also reflect that those participating in the study and completing bimonthly questionnaires are already more engaged.

Limitations

cannot be certain. Additionally, only costs associated with inpatient admissions were assessed. Multivariate analyses controlled for a range of demographic and illness-related covariates, however, models are not exhaustive and additional factors which could impact the relationship between decision making and service use might have been overlooked.The sample examined was heterogeneous, with mixed diagnoses and co-morbidities and patients were treated in different clinics by different clinicians. The staff also came from a diversity of professional backgrounds. Whilst heterogeneity might limit the conclusions that can be drawn about the relationship between CDM preferences and experiences and service use, the real world nature of the study increases the generalizability of the findings and builds on the recommendation for naturalistic CDM research (2,4).

Conclusions

References

1. Laugharne R, Priebe S: Trust, choice and power in mental health: a literature review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 41:843–852, 2006

2. Drake RE, Cimpean D, Torrey WC: Shared decision making in mental health: prospects for personalized medicine. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 11:455–463, 2009

3. van der Krieke, Lian, Emerencia AC, Boonstra N, et al: A web-based tool to support shared decision making for people with a psychotic disorder: randomized controlled trial and process evaluation. Journal of Medical Internet Research 15:e216, 2013

4. Salyers MP, Matthias MS, Fukui S, et al: A coding system to measure elements of shared decision making during psychiatric visits. Psychiatric Services 63:779–784, 2012

5. Calsyn RJ, Winter JP, Morse GA: Do consumers who have a choice of treatment have better outcomes? Community Mental Health Journal 36:149–160, 2000

6. Duncan E, Best C, Hagen S: Shared decision making interventions for people with mental health conditions. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews:CD007297, 2010

7. Legare F, Witteman HO: Shared decision making: examining key elements and barriers to adoption into routine clinical practice. Health Affairs 32:276–284, 2013

8. Veroff D, Marr A, Wennberg DE: Enhanced support for shared decision making reduced costs of care for patients with preference-sensitive conditions. Health Affairs 32:285–293, 2013

9. Drake RE, Deegan PE, Rapp C: The promise of shared decision making in mental health. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 34:7–13, 2010

10. McCabe R, Priebe S: Communication and psychosis: it's good to talk, but how? The British Journal of Psychiatry 192:404–405, 2008

11. Torrey WC, Drake RE: Practicing shared decision making in the outpatient psychiatric care of adults with severe mental illnesses: redesigning care for the future. Community Mental Health Journal 46:433–440, 2010

12. De las Cuevas, Carlos, Rivero A, Perestelo-Perez L, et al: Psychiatric patients' attitudes towards concordance and shared decision making. Patient Education and Counseling 85:245–250, 2011 13. Woltmann EM, Whitley R: Shared decision making in public mental health care: perspectives from

consumers living with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 34:29–36, 2010 14. Hamann J, Cohen R, Leucht S, et al: Do patients with schizophrenia wish to be involved in

decisions about their medical treatment? The American Journal of Psychiatry 162:2382–2384, 2005

15. Edwards K: Service users and mental health nursing. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 7:555–565, 2000

16. Dwight-Johnson M, Unutzer J, Sherbourne C, et al: Can quality improvement programs for depression in primary care address patient preferences for treatment? Medical Care 39:934–944, 2001

17. Mahone IH: Shared decision making and serious mental illness. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 22:334–343, 2008

18. Stein BD, Kogan JN, Mihalyo MJ, et al: Use of a computerized medication shared decision making tool in community mental health settings: impact on psychotropic medication adherence. Community Mental Health Journal 49:185–192, 2013

19. Adams JR, Drake RE: Shared decision-making and evidence-based practice. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 42:87–105, 2006

20. Matthias MS, Salyers MP, Rollins AL, et al: Decision making in recovery-oriented mental health care. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 35:305–314, 2012

21. Puschner B, Steffen S, Slade M, et al: Clinical decision making and outcome in routine care for people with severe mental illness (CEDAR): study protocol. BMC Psychiatry 10:90, 2010

23. Möller HJ, Jäger M, Riedel M, et al: The Munich 15-year follow-up study (MUFSSAD) on first-hospitalized patients with schizophrenic or affective disorders: assessing courses, types and time stability of diagnostic classification. European Psychiatry 26:231–243, 2010

24. Slade M, Powell R, Rosen A, et al: Threshold Assessment Grid (TAG): the development of a valid and brief scale to assess the severity of mental illness. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric

Epidemiology 35:78–85, 2000

25. Chisholm D, Knapp MR, Knudsen HC, et al: Client Socio-Demographic and Service Receipt Inventory--European Version: development of an instrument for international research. EPSILON Study 5. European Psychiatric Services: Inputs Linked to Outcome Domains and Needs. The British Journal of Psychiatry:s28-33, 2000

26. Slade M, Jordan H, Clarke E, et al: The development and evaluation of a five-language multi-perspective standardised measure: clinical decision-making involvement and satisfaction (CDIS). BMC Health Services Research 28:323, 2014

27. Puschner B, Neumann P, Jordan H, et al: Development and psychometric properties of a five-language multiperspective instrument to assess clinical decision making style in the treatment of people with severe mental illness (CDMS). BMC Psychiatry 13:48, 2013

28 Clarke E, Puschner B, Jordan H, Williams P, Konrad J, Kawohl W, Bär A, Rössler W, Del Vecchio V, Sampogna G, Nagy M, Süveges A, Krogsgaard Bording M, Slade M Empowerment and satisfaction in a multinational study of routine clinical practice, Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, in press).

29. Jabbar F, Casey P, Schelten SL, et al: What do you think of us? Evaluating patient knowledge of and satisfaction with a psychiatric outpatient service. Irish Journal of Medical Science 180:195– 201, 2011

29. Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, Arora NK, Gueguen JA, Makoul G. Patient preferences for shared decisions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2012; 86(1): 9-18; Duncan E, Best C, Hagen S.

30. Decoux M: Acute versus primary care: the health care decision making process for individuals with severe mental illness. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 26:935–951, 2005

31. Hamann J, Mendel R, Reiter S, et al: Why do some patients with schizophrenia want to be engaged in medical decision making and others do not? The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 72:1636–1643, 2011

32. Cummings SM, Cassie KM: Perceptions of biopsychosocial services needs among older adults with severe mental illness: met and unmet needs. Health & Social Work 33:133–143, 2008 33. Hamann J, Mendel R, Meier A, et al: "How to speak to your psychiatrist": shared decision-making

training for inpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 62:1218–1221, 2011

Table 1. Self-reported service use at baseline and 12-month follow up (N =578)

Baseline 12-month

follow up

Total Md IQR Total Md IQR Za P-valueb

Inpatient days (previous year) 6547 0.0 0.0-1.0 2871 0.0 0.0-0.0 -4.31 >.001

Inpatient stays (previous year) 201 0.0 0.0-1.0 137 0.0 0.0-0.0 -4.31 >.001

Outpatient visits (previous 3 months) 2716 1.0 1.0-6.0 3165 2.0 2.0-5.0 -0.27 .787

Day services (previous 3 months) 2683 0.0 0.0-1.0 2236 0.0 0.0-0.0 -1.74 .081

Community contacts (previous 3 months) 5769 5.0 1.0-14.0 5106 5.0 5.0-12.0 -2.42 .016

Psychotropic medications (previous month) 1555 2.0 2.0-4.0 1332 2.0 1.0-3.0 -2.25 .024