Cowlitz County

Drug Court Evaluation

Prepared by

:Nick McRee, Ph.D.

Principal InvestigatorMark Krause, Ph.D. Laurie Drapela, Ph.D.

Consultants

Research Assistants:

Kate Wilson, Jillian Schrupp, Jen Haner

Department of Social & Behavioral Sciences

The University of Portland 5000 N. Willamette Blvd.

Portland, Oregon 97203 (P) 503-943-7258 (F) 503-943-7802 mcree@up.edu

Table of Contents

A. Report Overview . . . .3

B. Executive Summary . . . .4

C. Cowlitz County Drug Court . . . .6

D. Research Design & Methodology . . . .10

E. Findings . . . 15

F. Implications of Findings . . . 36

G. References . . . .46

A.

REPORT OVERVIEW

The Cowlitz County Drug Court was established by the Cowlitz County Superior Court in August 1999. The Drug Court is a diversion program for offenders charged with drug offenses or other qualifying crimes. The Drug Court team approached Dr. Nick McRee, an Assistant Professor of Sociology and Criminal Justice at the University of Portland, to conduct an evaluation of the program. Dr. Mark Krause, Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of Portland, and Dr. Laurie Drapela, Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice at Washington State University—Vancouver served as consultants to this research. Dr. McRee and his research team designed an outcome evaluation for the Cowlitz County Drug Court program.

This evaluation report contains several sections. An executive summary of major findings is presented in Section B. Section C presents an overview of the mission of the Cowlitz County Drug Court program and outlines program components. Section D describes the research design and methodology

employed in the evaluation, including data collection and data management procedures. Section E presents findings from the evaluation. Specifically, it: (1) provides descriptive information about Drug Court participants; (2) compares clients terminated from the program with clients who graduated from the program, and focuses special attention on the disciplinary

infractions each group received; and (3) investigates recidivism rates among Drug Court graduates, clients terminated from the program, and offenders who were identified as suitable for the program but declined to participate. Section F presents an analysis of key findings from this evaluation in light of past research on drug courts. It also describes several implications of this research for the future and makes recommendations for improving data collection and data management. References and appendices to the report are contained in Sections G and H, respectively.

B.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1. Nick McRee, Ph.D., conducted an evaluation of the Cowlitz County Drug Court. The evaluation involved clients who entered the Drug Court program between August 1999 and September 2003. The study also included offenders who declined to participate in the program and were processed through the traditional criminal justice system.

2. In most respects, Drug Court participants and the sample of offenders who declined to participate in the program were similarly constituted, according to an analysis of group demographics, living arrangements and employment history, prior drug use, and criminal history. Some important differences were discovered, however. Drug Court clients tended to be slightly younger. They were also more likely to be employed or actively seeking employment at the time they were first screened for the program, and a lower proportion of Drug Court clients received public assistance. Drug Court participants reported greater frequency of drug use in the month prior to their eligibility screening, but they were less likely to have a felony or misdemeanor criminal record.

3. The evaluation considered sanction activity among Drug Court graduates and clients who were terminated from the program. Both groups tended to receive a similar number of sanctions on average (6.59 sanctions for

graduates compared to 8.29 for those terminated from the program). However, a majority of graduates remained sanction-free during the first 30 days of the program, while less than 1/3 of clients terminated from Drug Court managed to receive no sanctions during their first month in the program. Indeed, 50% of non-graduates received a sanction within the first two weeks in Drug Court. By contrast, the graduate cohort spent approximately 6 weeks in the program before 50% had received a sanction.

4. The odds that a Drug Court client would successfully complete the program were computed to be 44.4%. This is essentially the same

graduation rate that has been observed in other evaluations of drug courts around the country. The study also discovered factors that are associated with the probability of graduation. Male clients were less likely than females to graduate. Married clients were almost 3 times more likely to graduate than those who were not married. A client who was working full-time when they began the program was over 4 full-times more likely to

graduate than others who were unemployed or working part-time. Clients who lived alone were about 1/3 less likely to graduate. Finally, clients who received two or more sanctions within the first 30 days of entering Drug Court were only half as likely to graduate. However, no association was observed between the number of sanctions a client received and the probability they would successfully graduate from Drug Court. This

suggests that the critical issue between sanctions and graduation may not be how many sanctions that offenders receive but rather how quickly

clients receive them after entering the program.

5. The study examined recidivism rates (measured as a new felony arrest) among Drug Court graduates, clients who entered Drug Court but failed to graduate, and offenders who declined to participate. The analyses revealed that recidivism was significantly lower among Drug Court graduates than the other groups. Over 90% of graduates had no felony arrest one year after release, and about 75% of graduates remained felony arrest-free up to three years after completing the program. The low rate of recidivism observed among Cowlitz County Drug Court graduates is

similar to results reported by other evaluations of drug courts in

Washington State and across the country. Clients who failed to complete Drug Court were approximately 3 times more likely than graduates to have a new felony arrest. Offenders who declined to participate in the program were almost 5 times more likely to recidivate than graduates were.

6. In light of the evaluation results, recommendations are offered to improve program efficiency and performance.

C.

COWLITZ COUNTY DRUG COURT

This section of the report outlines the mission of the Cowlitz County Drug Court and defines the policies and procedures of the program.

1. Mission

The Drug Court is a Cowlitz County Superior Court program that offers qualified offenders an opportunity to enter Court-supervised treatment for drug and alcohol addiction. The program is available to persons who have admitted problems with drugs and/or alcohol and have been charged with an eligible offense. Upon successful completion of the Drug Court program, offenders can have their current charge(s) dismissed.

The mission of the Drug Court is to provide effective drug/alcohol treatment to eligible non-violent/non-sex offenders, thereby reducing crime and

improving the quality of life in the community (Cowlitz County Drug Court Policies and Procedures Manual, 2003). The specific goals established for the program are:

• Reduce criminal recidivism by providing assessment, education and treatment to drug/alcohol addicted criminal offenders.

• Monitor treatment compliance through frequent court contact and supervision.

• Require strict accountability for program participants and impose immediate sanctions for unacceptable behavior.

• Reallocate resources to provide an effective alternative to

traditional prosecution and incarceration of non-violent/non-sex offenders.

• Reduce costs within the County’s criminal justice system.

• Concentrate available criminal justice resources on more violent offenders.

2. Process

Agents involved in the Cowlitz County Drug Court include the Superior Court Judge assigned to the Drug Court, the Superior Court Clerk, the Prosecuting Attorney’s Office and Defense Attorneys, the Drug Court Coordinator and additional members of the Department of Corrections, substance abuse and mental health treatment providers, and local law enforcement agencies.

The Cowlitz County Drug Court Policies and Procedures Manual (2003) identifies eligibility requirements and disqualifying factors for Drug Court candidates. Promptly after arrest, the County Prosecutor, the Defense

Attorney, or the Drug Court Coordinator may recommend an initial eligibility review to determine if offenders meet requirements to enter the Drug Court program. The County Prosecutor makes recommendations based on current charges and prior criminal history. The Drug Court Coordinator evaluates suitability of defendants for the program based on compliance and

community screening factors. If these screenings suggest suitability for the Drug Court program, the Drug Court Coordinator schedules a drug/alcohol assessment with a Drug Court treatment provider. The treatment providers ensure that offenders meet addiction and mental health criteria. Absent special circumstances, application for entry into Drug Court must be made within 30 days of the date that criminal charges are filed.

The Drug Court team continues to closely supervise and assist the

participant throughout their time in the program. The Drug Court Judge retains full jurisdiction of the entire process and oversees client progress. In particular, the Drug Court has established specific procedures regarding courtroom behavior and decorum, the collection from clients of court-ordered restitution and mandatory participation fees, supervision fees, and other program costs.

Consistent with standards established with other drug courts around the nation, the Cowlitz County Drug Court program consists of four treatment

phases: Phase I (stabilization, orientation, and assessment); Phase II (intensive outpatient treatment and assessment); Phase III (transitional, phased treatment and assessment); and Phase IV (aftercare). Each phase requires clients to attend Drug Court, keep scheduled appointments with the Drug Court Coordinator, participate in all required treatment and group therapy sessions, submit to urinalysis and other drug testing as required, and otherwise comply with all requirements established for the particular phase of treatment. Advancement of clients between phases is determined by the Drug Court Judge with the condition that the participant has satisfied the criteria established in the Cowlitz County Drug Court Policies and Procedures Manual (2003). Clients graduate from the program after

successful completion of all phases of treatment. Upon successful completion of Drug Court, clients are eligible to have the current criminal charges against them dismissed.

The Drug Court includes a plan for close monitoring of offender behavior and compliance with Drug Court policies. A system of progressive sanctions and rewards has been established to assist the Drug Court Judge to encourage client compliance with program requirements. Sanctions for non-compliance may include any or all of the following:

• Increased drug testing

• Increased participation in outpatient sessions

• Increased frequency of court appearances before the Drug Court Judge

• Increased attendance at community support groups

• Referral to other community resources

• Community service / Work Crew

• Commitment to community residential treatment

• Jail

• Electronic monitoring

The Drug Court Judge may also recognize client positive behavior and compliance with program requirements. Such recognition can include:

• Promotion to the next phase of the program

• Award of certificates marking progress in the program

• Award of coins to recognize continued sobriety

• Court Orders to waive supervision fees

• Gift certificates to reward certain tasks completed (e.g., gaining employment)

Clients who do not comply with Drug Court requirements are subject to termination from the program by the Drug Court Judge. Clients can be expelled from the Cowlitz County Drug Court for any of several reasons:

• Client accumulates new criminal charges

• Continual failure to comply with program requirements

• Tampering with drug tests or testing equipment

• Unsuccessful discharge from treatment

• Extended periods of time on warrant status

D.

RESEARCH DESIGN & METHODOLOGY

1. Outcomes Evaluation Goals

This section outlines the evaluation methodology used in the study. Evaluation research attempts to ascertain the impacts that an action or treatment has on society or an individual. It is also used to measure the impact of government policy or other social interventions (Schutt, 1999). A significant amount of research on drug courts in the US has demonstrated that they represent a cost-effective method for criminal justice systems to deal with offenders with drug problems. Indeed, as Marlowe, DeMatted and Festinger (2003) note, "drug courts outperform virtually all other strategies that have been attempted for drug-involved offenders." However, there is a significant amount of variation around the country with respect to how particular drug courts operate. This means that evaluation research is needed that is tailored to particular programs. The research conducted for this project focuses primarily on the effectiveness of the Cowlitz County Drug Court in meeting the goal of reducing criminal behavior. This is accomplished by profiling characteristics of Drug Court participants and others that did not participate in the program. The study explores whether those who graduated from the program had different experiences, levels of treatment, recidivism, and/or drug use than those that were terminated from the program.

Additional information is provided by comparing drug court clients with a sample of offenders identified as suitable candidates for the program but who declined to participate.

2. Study Design

The Cowlitz County Drug Court contracted with Dr. Nick McRee, of the University of Portland’s Department of Social & Behavioral Sciences, to design and implement an evaluation of the Drug Court program. Because the program had been in operation for several years when the evaluation was commissioned, it was not feasible to conduct a controlled experiment wherein

offenders were randomly assigned either to participate in the Drug Court or to be processed through the traditional criminal justice system. The inability to randomly assign offenders to participate in the program poses a challenge to determining program effectiveness. For example, offenders differ in

motivation and personal commitment to rehabilitation. They may also vary in other factors (such as prior participation in residential or outpatient drug treatment programs) that could be associated with program success or lower recidivism.

However, the Drug Court team retained a significant amount of data on offenders to allow four groups to be drawn for comparison. One group consists of offenders who were active in the program as of September 2003. A second group includes all graduates of the Drug Court since the program began in August 1999. A third group includes all offenders who were admitted to Drug Court but later terminated from the program. A final group contains a

sample of offenders that were identified as suitable candidates for Drug Court but who subsequently declined to participate. Although not as rigorous as a random assignment experimental design, the identification of these populations allows the evaluation to investigate the Drug Court program and its ability to reduce criminal recidivism.

3. Data Collection

The primary source of data for this evaluation is derived from the Cowlitz County Drug Court Database. This database is maintained by the Drug Court team. The data intake process begins when the Drug Court

Coordinator interviews potential candidates and evaluates their suitability for the program. A client status form in the database allows a member of the Drug Court Team to enter information about the referral process and the offender’s suitability for the program. A client demographic form contains demographic information, employment and residence status, and educational achievement at the time the candidate is assessed for program eligibility. History of substance abuse and medical history at time of intake are recorded, and a criminal history form allows the Drug Court team to note

prior conviction dates and types of convictions. For offenders who decline to participate in the program, this is the extent of data that is collected.

A court hearing form allows the Drug Court Coordinator to track each client’s progress in the Drug Court program. The form includes information about the phase of treatment a client was in, sanctions a client may receive, and special considerations that may be noted by members of the Drug Court team. In addition, each week the Drug Court team meets to discuss the status of the clients. Clients are evaluated by the members of the team each time they are scheduled to report to the Judge in open court, and at other times when circumstances warrant (e.g., if the client violates a condition of supervision).

In September 2003, deputies with the Cowlitz County Department of

Corrections conducted criminal background checks on all offenders not active in the Drug Court as of September 2003. The records generated from these background checks were used to calculate criminal recidivism. This study defines criminal recidivism in terms of new felony arrests.1 For Drug Court

graduates, criminal histories were reviewed after the date of graduation. For clients who were terminated from the Drug Court, criminal histories were checked after the date that the client was released from the program (and after any time of incarceration to which they had been sentenced). For offenders who declined to participate in Drug Court, criminal histories were checked after the date the offender declined to participate, including any period of jail or incarceration that was served for the current charge(s). 4. Data Management

Dr. McRee reviewed the criminal history data for each client or offender, and his research assistants input the criminal histories into a statistical analysis program. These data were then merged with data from the Cowlitz County Drug Court database. Reported totals may not equal 100% due to rounding or because some questions allow more than one answer per respondent.

1Some offenders are arrested but not subsequently convicted or incarcerated. Recidivism

rates based on measures of re-arrest will therefore be higher than recidivism measures derived from conviction rates or incarceration rates.

Additionally, two types of missing data occur in this study: 1) data was not gathered on all variables for all individuals; and, 2) information was not available for different types of clients on all variables.

There were 398 unique records in the master client table when it was downloaded from the Drug Court computer system on 04 September 2003 and provided to Dr. McRee for analysis. Active clients include individuals who were participating in the program at that time. A small number of these active clients many have been in jail serving a sanction or ordered by the Drug Court Judge to a period of residential treatment. The active offender group also includes clients who may have temporarily absconded from the program, or who may have been admitted to the program but not yet started treatment. The database also contained records for successful graduates, offenders who either had been terminated from the Drug Court or who decided to withdraw before completion of the program. In addition,

information was available for offenders who declined to participate in the program. Still other individuals were in the database but had temporary or unusual statuses (e.g., offenders who had absconded from the program but no final disposition on their case had yet been made). Table 1 provides a

breakdown of how offenders were recoded. Of the 398 cases in the original database, 4 had unidentifiable statuses and were excluded from the analysis.

Table 1: Drug Court Sample of Participants, Aug 1999—Sept 2003 Offender

Status

Original Status in

Drug Court Database N % 2

Active Active In Custody Inpatient Pending Warrant 112 70 7 4 8 23 28.1% Graduates Dismissal 91 91 22.8% Terminated Terminated/Neutral Terminated/Unsuccessful Participant Requested 114 3 105 6 28.6% Declined Declined 45 45 11.3% Denied Denied Ineligible3 32 31 1 8.0% Missing3 Missing Data

Transferred to other county

4

1 3

1.0%

TOTAL 398 100%

2

Percentages do not equal 100 due to rounding. 3 Cases are excluded from further analyses.

E.

FINDINGS

1. Comparison of clients who did / did not enter Drug Court

In this first portion of the analysis, we examine the characteristics of clients in the Drug Court program (N=317). This group includes offenders active in the program as of September 2003 (N=112), as well as program graduates (N=91) and those who entered the program but failed to graduate (N=114). We compare these clients with a group of offenders who did not participate in the program (N=77). In addition, we provide demographic data for Cowlitz County in 2000 for comparative purposes.

Table 2 reveals that the demographic characteristics of clients who entered Drug Court and the offenders who did not are similar in most respects. The ratio of males to females in both groups is close to 50/50, although there is a slightly greater proportion of males in Drug Court than in the group of offenders who did not participate in the program. The race and ethnic breakdown of both groups is similar as well, with more than 90% of each group identified as White. (The table also shows that the gender, race and ethnic characteristics of both groups are comparable to the Cowlitz County population in 2000.) However, differences are observed in the age

distributions for both groups. Offenders that did not enter Drug Court are (on average) older than Drug Court clients, while the Cowlitz County population as a whole is significantly older than both groups.

For marital status, the data reveal a greater proportion of Drug Court clients that are married. However, a substantial number of offenders who declined Drug Court had missing data for their marital status, rendering it difficult to draw any conclusions about this characteristic. It is not surprising to note that the Cowlitz County population in 2000 shows a much higher proportion of residents who are married. In terms of education, 46.2 % of Drug Court clients reported having a high school degree or a GED, a proportion slightly higher than the non-Drug Court group. Over one-half of those who did not enter Drug Court had no high school degree, while 43.8% of Drug Court

Table 2: Demographics of Clients Who Did/Did Not Enter Drug Court

Attribute

Entered Drug Court

(N=317)

Did not enter Drug Court (N=77) Cowlitz County Population (2000 census) Gender Female Male 47.9% 52.1% 53.2% 46.8% 50.7% 49.3% Race White Black Hispanic Native American Asian Other 93.1% 1.9% 1.6% 2.8% 0.0% 0.6% 92.2% 3.9% 1.3% 1.3% 1.3% 0.0% 91.8% 0.5% 4.6% 1.5% 1.3% 2.1% Age 18-19 20-29 30-39 40-49 50+ 14.8% 40.7% 30.6% 11.4% 1.6% 10.4% 33.8% 41.6% 11.7% 1.3% 19.3% 14.7% 14.6% 19.6% 38.1% Education High School / GED Associates Degree Vocational

BA / BS degree Post-Graduate No Degree 46.2% 5.0% 4.4% 0.3% 0.3% 43.8% 40.3% 0.0% 2.6% 1.3% 0.0% 55.8%

(82.3% of County residents age 25 and

older have at least a high school degree)

Marital Status Married Never Married Divorced Separated Widowed

Unknown / Missing Data

15.1% 52.1% 21.8% 6.3% 0.9% 3.8% 2.6% 37.7% 14.3% 11.7% 0.0% 33.7% (age 15+) 56.2% 20.7% 12.4% 3.9% 6.8% 2.1%

clients had not earned a high school degree or GED. County-level data in 2000 shows that 83.2% of Cowlitz County residents have a level of education at or above the high school level.

Table 3 provides additional data about residential characteristics and

employment status of offenders, as well as whether they were receiving some form of public assistance. These data report what the offenders in the sample looked like at the time they were first interviewed by the Drug Court team. If available, county-level data from the 2000 census are also provided. Table 3 reveals a significant amount of missing data concerning the living

arrangements of offenders who did not participate in Drug Court, making accurate comparisons with Drug Court clients difficult. However, the results tend to show that a substantial number of Drug Court clients were living in “non-household” arrangements (e.g., shelters or transient living) at the time they opted into the program. By contrast, over 98% of the Cowlitz County population resided in a household in 2000. The table also shows that the living arrangements of Drug Court clients and non-participants were quite varied.

Although more than 60% of the Cowlitz County population over 16 years of age were employed in some capacity during 2000, at their initial screening less than 20% of Drug Court clients and those who declined to participate reported working for pay in a full-time or part-time job. However, almost one-half of Drug Court clients were seeking work when they entered the program, while only about 1 in 3 non-participants reported seeking work when the Drug Court team interviewed them. Some of this discrepancy appears to be due to the fact that a much larger proportion of non-participants reported being disabled or otherwise unable to work, compared to Drug Court clients. More than 1 in 5 Drug Court clients received public assistance, compared to 45% of non-participants. (By comparison, slightly more than 8% of Cowlitz County residents received any form of government assistance in 2000.)

Table 3: Housing, Employment & Income of Clients Who Did/Did Not Enter Drug Court

Attribute

Entered Drug Court

(N=317)

Did not enter Drug Court

(N=77)

Cowlitz County Population

Type of Residence Household

Jail / Prison Shelter Transient

Unknown / Missing Data

85.2% 0.9% 8.8% 1.6% 3.5% 62.3% 0.0% 2.6% 2.7% 32.4% 98.5% 1.0% 0.5% ---Living Arrangement Alone With child Friends Parents

Parents & child Partner

Partner & child Other Family

Unknown / Missing Data

12.6% 5.7% 11.7% 9.1% 14.2% 7.3% 16.4% 18.9% 4.1% 7.8% 5.2% 10.4% 14.3% 2.6% 2.6% 13.0% 10.4% 33.7% Employment Status Full-Time Part-Time Student Seeking work Not Seeking Work Homemaker

Unable to work / Disabled

10.4% 9.2% 4.8% 45.7% 21.8% 1.6% 6.4% 9.0% 6.5% 0.0% 35.1% 28.6% 2.6% 18.2%

61% of persons over 16 years of age in Cowlitz County were

in the labor force (full-time or

part-time) in 2000

Public Assistance

In Table 4, we examine the drug use history of Drug Court clients and

offenders who did not participate in the program. Subjects were asked about 5 different types of substances: alcohol, cocaine, heroin, marijuana, and “other” drugs. (The Drug Court Coordinator has noted that the category of “other” typically refers to methamphetamine, and this was corroborated through a review of information contained in the Drug Court database.) Each person interviewed by the Drug Court team was asked which of these

substances represented their “primary” and “secondary” drugs of choice. The data in Table 4 show that the drug use history of Drug Court clients and offenders who did not participate in the program were similar in some respects. No meaningful differences were discovered between the groups in terms of their primary or secondary drug of choice. (It is important to note that data were missing for a large number of offenders who did not

participate in Drug Court, making firm conclusions difficult to draw about the similarity of this group to Drug Court clients.) More than 50% of both groups identified marijuana or other (methamphetamine) as their primary drug of choice. Most of the subjects also identified a different illicit substance as a secondary drug of choice, indicating that a majority of both groups

exhibit poly-drug consumption patterns.

If subjects reported ever having used a particular drug, they were asked to identify the age at which they first used the drug, as well as their frequency of use in the month prior to the interview. Table 4 shows that the average age at which offenders starting using particular substances is fairly similar

between the two groups. (The notable exception is average age at first use of heroin: among offenders who have used heroin, Drug Court clients tended to initiate use about 4 years earlier than non-participants.)

Significant differences were observed between Drug Court clients and non-participants in terms of the frequency of drug use in the month prior to the interview. For each drug, offenders were flagged as “frequent” users of a particular substance if they reported a frequency of consumption in the previous month equal to or greater than 1-2 times a week. The data in Table 4 show that for each type of drug, a larger proportion of Drug Court clients

Table 4: Drug History of Clients Who Did/Did Not Enter Drug Court

Attribute

Entered Drug Court

Did not enter Drug Court

Primary Drug of Choice Alcohol

Cocaine Heroin Marijuana

Other / Methamphetamine

(N = 303) 11.5% 10.2% 18.5% 22.1% 37.6%

(N = 47) 10.6% 17.0% 17.0% 21.2% 34.0%

Secondary Drug of Choice Alcohol

Cocaine Heroin Marijuana

Other / Methamphetamine

(N = 280) 18.6% 17.5% 5.7% 29.6% 28.6%

(N = 39) 23.1% 15.4% 2.6% 33.3% 25.6%

Age at First Use

Alcohol Cocaine Heroin Marijuana

Other / Methamphetamine

(N = 317) 14.2 19.0 20.9 14.0 19.7

(N = 77) 13.7 18.8 24.9 13.6 19.6

Frequency of Use in Past Month

Alcohol—more than 1-2 times / week Cocaine—more than 1-2 times / week Heroin—more than 1-2 times / week Marijuana—more than 1-2 times / week Other / Meth—more than 1-2 times / week

(N = 317) 27.1% 20.2% 19.2% 36.6% 43.5%

(N = 77) 13% 13% 11.7% 20.8% 24.7%

reported frequent use in the prior month. For example, about 1 in 4 non-participants reported regular consumption of methamphetamine/other drugs in the past month, while almost one-half of Drug Court clients reported frequent use of these substances.

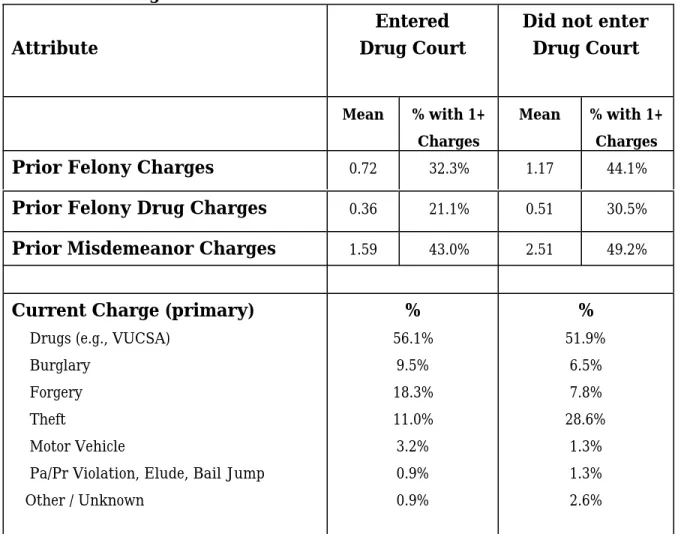

Table 5: Criminal History & Current Offenses of Clients Who Did/Did Not Enter Drug Court

Attribute

Entered Drug Court

Did not enter Drug Court

Mean % with 1+

Charges

Mean % with 1+

Charges

Prior Felony Charges 0.72 32.3% 1.17 44.1%

Prior Felony Drug Charges 0.36 21.1% 0.51 30.5%

Prior Misdemeanor Charges 1.59 43.0% 2.51 49.2%

Current Charge (primary)

Drugs (e.g., VUCSA) Burglary

Forgery Theft

Motor Vehicle

Pa/Pr Violation, Elude, Bail Jump Other / Unknown

%

56.1% 9.5% 18.3% 11.0% 3.2% 0.9% 0.9%

%

51.9% 6.5% 7.8% 28.6%

1.3% 1.3% 2.6%

In a final set of comparisons between Drug Court clients and non-participants, we examine the criminal histories and current (primary) charges for each group. These data are reported in Table 5. The Drug Court database contains information about the number of felony arrests, felony drug arrests, and misdemeanor arrests incurred by each offender prior to the current set of criminal charges. We calculated the mean number of arrests levied against Drug Court clients and non-participants, and also report the proportion of offenders in each group that had one or more prior arrests. The data in Table 5 clearly shows that, compared to non-participants, Drug Court clients have a lower average number of prior misdemeanor charges and felony charges (including felony drug charges). In addition, the proportion of Drug Court clients with one or more prior misdemeanor or felony charges is lower than the sample of offenders who declined Drug Court. In sum, Drug

Court clients are less likely to have a criminal history than non-participants, and among those that do have a prior record, it is typically less extensive than the number of offenses accumulated by those who decline to participate in the program. With respect to offenders’ current (primary) criminal charge, Table 5 shows that although offenders and clients were charged with a

variety of offenses, over 50% of both groups had a drug-specific charge pending (e.g., VUCSA, or Violation of Uniform Controlled Substances Act). 2. Comparison of Drug Court graduates and clients that did not complete Drug Court

One of the key objectives for this evaluation is to identify factors that are associated with successful completion of the Drug Court program. We turn our attention to this question in this section of the report. Offenders who declined to participate in the program are excluded from this portion of the analysis, as are clients who were still active in the program when the data collection process began. We examine the characteristics of Drug Court

clients who entered the program and either graduated successfully or did not complete the program.

Unfortunately, much of the database does not reflect changes that may occur for a client as they progress through the program (e.g., changes in

employment status or living arrangements). As a result, most of the variables we consider in this study are static, in the sense that the data represent what the clients looked like at the time they entered the program. Even so, it is important to consider whether these data may predict successful completion of the Drug Court program.

We are also interested in determining how a client’s behavior while in the program might predict program success. One measure of behavior is the record of sanctions that may be accrued as offenders move through the program. In Table 6, we evaluate the sanction history of Drug Court

graduates and clients terminated from the program, and look for differences in sanctioning events. At the top of Table 6, the mean number of sanctions received by each group is reported, along with the proportion of each group

Table 6: Sanction History of Drug Court Graduates & Clients Terminated From Program—Demographic Factors

Drug Court Graduates

Terminated From Program

Client Attribute Mean #

Sanctions

% Sanction-Free After 30 Days

Mean # Sanctions

% Sanction-Free After 30 Days

Total Sample 6.59 57.0% 8.29 31.8%

Gender Female Male 6.97 6.13 55.3% 51.3% 6.73 9.63 30.6% 29.5% Age 18-19 20-29 30-39 40-49 4.82 6.21 5.86 10.91 54.5% 55.2% 59.4% 53.8% 10.05 6.46 8.42 11.38 21.1% 39.0% 32.4% 23.1% Marital Status Married Never Married Divorced Separated 3.47 6.74 8.71 5.80 64.7% 53.8% 54.5% 50.0% 8.63 8.78 7.28 8.22 33.3% 33.9% 30.8% 11.1% Living Arrangement Alone With child Friends Parents

Parents & child Partner

Partner & child Other Family 11.57 9.11 10.00 4.00 5.29 4.00 4.53 6.90 12.5% 45.5% 57.1% 75.0% 66.7% 62.5% 63.6% 50.0% 11.56 8.00 8.94 7.53 6.87 5.00 7.87 8.75 5.6% 25.0% 17.6% 33.3% 40.0% 45.5% 44.4% 41.2% Employment Full-Time Part-Time Seeking Work Not Seeking work

6.70 11.00 5.58 7.40 60.0% 36.4% 59.0% 45.5% 6.86 15.29 7.30 9.22 14.3% 50.0% 24.1% 42.3%

that remained “sanction-free” during the first 30 days in the program.

Although clients who were eventually terminated from the program received approximately two more sanctions (on average) than eventual graduates, the results show that both groups tended to receive a rather large number of sanctions while in the program (6.59 for graduates, and 8.20 for non-graduates). On the other hand, the majority of Drug Court graduates remained sanction-free during the first 30 days in the program, while less than 1 in 3 of the terminated clients remained sanction-free during the first 30 days of Drug Court.

We also examine sanctions between graduates and non-graduates by selected demographic characteristics. (Race and ethnicity are not considered here because almost all of the offenders in the sample were White.) First, among terminated clients the mean number of sanctions is much higher for males than for females, even though the proportions of both genders that received one or more sanctions within the first 30 days of the program is essentially the same. Second, among graduates and non-graduates, clients aged 40-49 were least likely to remain sanction-free in the beginning weeks of the

program. Additionally, terminated clients between 18-19 years of age tended to receive many more sanctions than terminated clients between 20-29 and 30-39 years of age. Third, Drug Court graduates who were married had a lower average number of sanctions, on average, than graduates who were divorced, separated, or never married. Fourth, graduates and non-graduates who lived alone tended to receive many more sanctions than clients in other living arrangements, and very few clients who lived alone managed to stay sanction free during the first 30 days of the program. Finally, a somewhat perplexing set of results is observed among clients who worked part-time. Both graduates and clients terminated from the program who worked part-time tended to have many more sanctions than other subjects did. For instance, graduates with part-time employment when they started Drug Court received an average of 11 sanctions before completing the program, compared to 7.4 received by eventual graduates who were unemployed and not seeking work when they started the program. Without additional details about the nature of the employment, it is difficult to explain these results. One possibility is that part-time work doesn’t represent as great a stake in

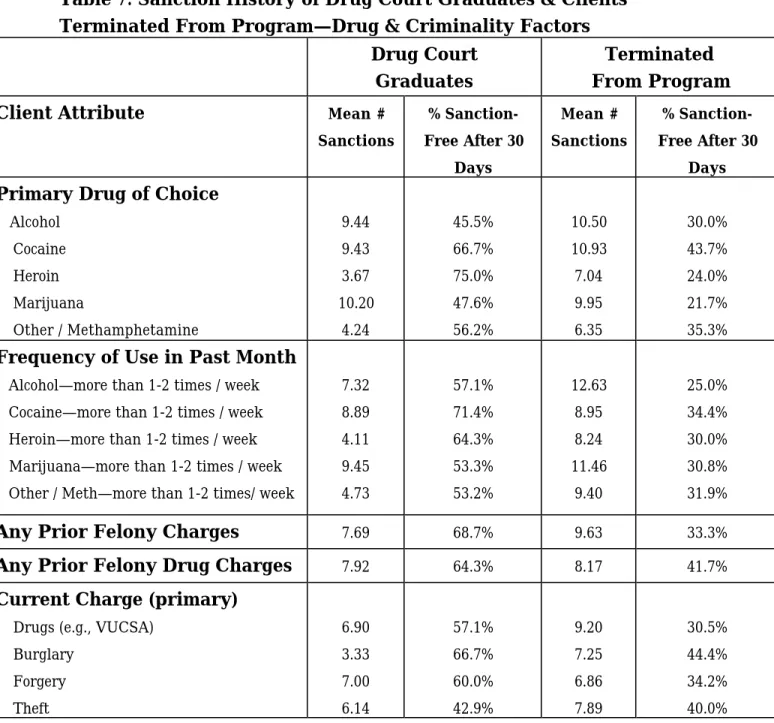

conformity as full-time work, but it may provide offenders with enough money to secure drugs and alcohol. It is also possible that some clients were attempting to simultaneously balance part-time work with school and/or family obligations, leading to role strain. Another limitation is that the data Table 7: Sanction History of Drug Court Graduates & Clients

Terminated From Program—Drug & Criminality Factors Drug Court

Graduates

Terminated From Program

Client Attribute Mean #

Sanctions

% Sanction-Free After 30

Days

Mean # Sanctions

% Sanction-Free After 30

Days

Primary Drug of Choice Alcohol

Cocaine Heroin Marijuana

Other / Methamphetamine

9.44 9.43 3.67 10.20 4.24 45.5% 66.7% 75.0% 47.6% 56.2% 10.50 10.93 7.04 9.95 6.35 30.0% 43.7% 24.0% 21.7% 35.3%

Frequency of Use in Past Month

Alcohol—more than 1-2 times / week Cocaine—more than 1-2 times / week Heroin—more than 1-2 times / week Marijuana—more than 1-2 times / week Other / Meth—more than 1-2 times/ week

7.32 8.89 4.11 9.45 4.73 57.1% 71.4% 64.3% 53.3% 53.2% 12.63 8.95 8.24 11.46 9.40 25.0% 34.4% 30.0% 30.8% 31.9%

Any Prior Felony Charges 7.69 68.7% 9.63 33.3%

Any Prior Felony Drug Charges 7.92 64.3% 8.17 41.7%

Current Charge (primary)

Drugs (e.g., VUCSA) Burglary Forgery Theft 6.90 3.33 7.00 6.14 57.1% 66.7% 60.0% 42.9% 9.20 7.25 6.86 7.89 30.5% 44.4% 34.2% 40.0%

only reflect the employment status of clients when they were initially

screened, and do not show how their employment history may have changed after starting Drug Court. Nevertheless, the data suggest it may be

somewhat premature to conclude that all forms of employment equally contribute to client success while in the program.

In Table 7, we extend our analysis of sanctions to consider client attributes relating to drug use and prior criminal history. A greater proportion of clients who eventually graduated from Drug Court (compared to non-graduates) remained sanction-free during the first 30 days of the program, regardless of the primary drug of choice. Moreover, graduates generally received a lower average number of sanctions than did terminated clients. (The only

exception—among offenders whose primary drug of choice was marijuana, graduates averaged 10.20 sanctions while non-graduates averaged 9.95—was not a statistically significant difference.) Among frequent drug users (i.e., more than 1-2 times per week in the previous month), non-graduates tended to receive more sanctions and were much less likely to remain sanction-free during the first month of the program. Among clients with prior felony charges, graduates were more likely to remain sanction-free during the first 30 days of the program, and they also tended to receive a lower average number of sanctions.

One central conclusion that can be drawn from the results in Tables 6 and 7 is that Drug Court graduates received fewer sanctions, and they were more likely to remain sanction-free during the first 30 days of the program. This tends to be the case regardless of particular demographic characteristics, drug use, criminal history, or current criminal charge. Although both

graduates and non-graduates on average tended to receive several sanctions during their time with Drug Court, a greater proportion of graduates

remained free of a sanction during the first 30 days of the program. Thus, it is conceivable that a client’s early behavior in Drug Court may be more

significant in predicting eventual graduation than a more general assessment of how many times their behavior may fall short of program expectations. In other words, the critical issue regarding the relationship between sanctions

and graduation may not be how many sanctions but rather how quickly do offenders receive sanctions after entering the program.

Table 8: Median Time to Sanction: Drug Court Graduates & Clients Terminated From Program

Drug Court Graduates

Terminated From Program

Median Days Before 1st Sanction

Median Days Before 2nd Sanction

Median Days Before 3rd Sanction

Median Days Before 1st Sanction

Median Days Before 2nd Sanction

Median Days Before 3rd Sanction 44 days 159 days 197 days 15 days 49 days 205 days

To consider this idea, we calculated the time that passed from the point that an offender entered Drug Court until the time that they received their first sanction. We continued this procedure for each sanction the client may have received before either graduating from Drug Court or being terminated from the program. In Table 8, we report the median number of days that passed before graduates and non-graduates received each additional sanction. The data in Table 8 support the conclusion drawn above: clients who eventually are terminated from Drug Court tend to receive their first two sanctions much earlier than graduates do. For non-graduates, the median number of days that elapsed before a first sanction was received was only 15 days. (This means that one-half of the non-graduates received at least one sanction within the first two weeks of entering Drug Court.) By contrast, the median time to first sanction for graduates was almost 3 times as long—44 days. An even larger difference is observed for second sanctions. The median amount of time that elapsed before Drug Court graduates received a second sanction was 159 days—about 5 months. For non-graduates, the figure is 49 days. Note that for third sanctions, the median figures are 197 and 205 for graduates and non-graduates, respectively. In essence, there is no meaningful difference between the groups in terms of the average time elapsed before the third sanction. (No substantive differences between the groups with respect to sanctions 4-10 were found, and thus these analyses are not presented.) These data tend to reinforce the notion that the behavior

of clients early in the program is a key distinguishing feature between individuals who will eventually graduate and those who will not.

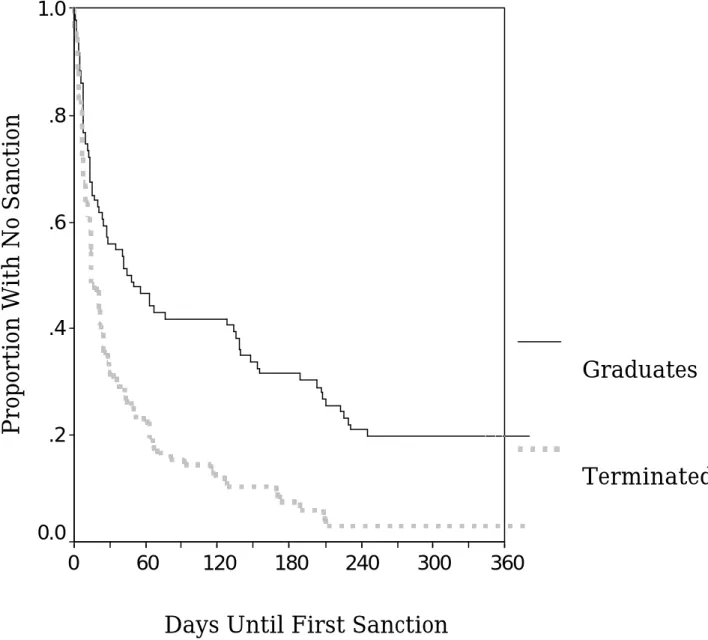

Figure 1: Survival Time to First Sanction: Drug Court Graduates & Clients Terminated From Program

To further illustrate the differences between the groups, Figure 1 shows the results of a survival analysis for time to first sanction among Drug Court graduates and non-graduates. When clients begin the Drug Court program, they are sanction-free. As time goes on, however, some of them will receive a

Days Until First Sanction

360

300

240

180

120

60

0

Proportion With No Sanction

1.0

.8

.6

.4

.2

0.0

Graduates

Terminated

sanction. Survival analysis is a statistical technique that allows us to calculate the probability that graduates and non-graduates will “survive” (i.e., remain sanction-free) within any particular period of time in Drug Court. Three conclusions can be drawn from Figure 1. First, it is apparent that most graduates and most non-graduates receive at least one sanction. Second, most graduates and non-graduates, if they do receive a sanction, tend to get it within the first 60 days of entering Drug Court. Third, it is clear that a greater proportion of graduates remain sanction-free throughout the first year of the program. Indeed, at about day 60, only about 20% of clients who will eventually be terminated from the program remained sanction-free. To complete our analyses of Drug Court clients, we perform a statistical procedure called logistic regression to identify factors that may predict whether a client admitted to Drug Court will successfully graduate from the program. In Table 9, we summarize the results of this procedure. (For

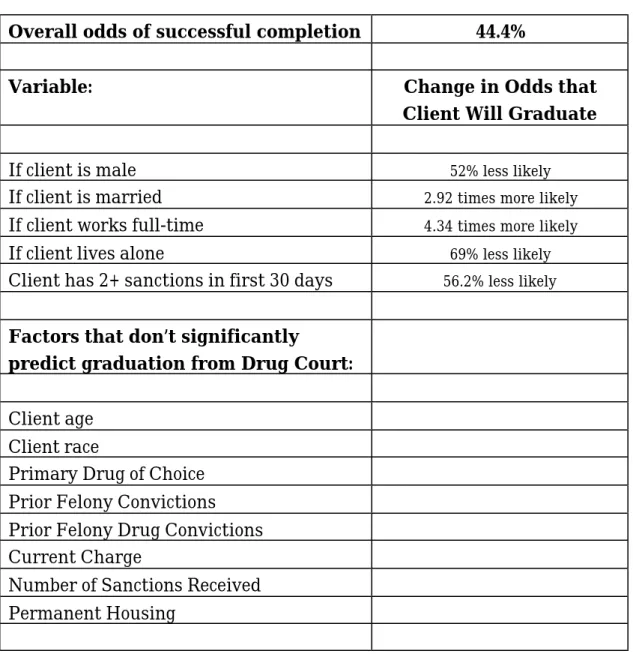

technically inclined readers, we provide the full results of the model and all statistical tests in Section H of this document.) Our analysis reveals that, without examining any other factors that might increase or decrease the probability that a client will graduate, the overall odds of successfully completing the program is 44.4%.

Our analysis also identified several factors that appear to predict graduation from the Drug Court. For example, other factors held constant, males were about half as likely as females to graduate. Another observed risk factor was if the offender lived alone at the time that they entered Drug Court.

Compared to clients with other living arrangements, these individuals were 69% less likely to graduate. A third risk factor was if the client received two or more sanctions with the first 30 days of entering Drug Court. These clients were less than half as likely to graduate, compared to others who did not earn multiple sanctions in the first weeks of the program. Interestingly, the total number of sanctions that a client received did not represent a

significant influence on the probability of graduation. Other factors

considered but found to not significantly alter the probability of graduation were client age or race, primary drug of choice, prior felony convictions (whether drug-related or not), or the primary criminal charge.

Table 9: Predicting Graduation From Drug Court Program

Overall odds of successful completion 44.4%

Variable: Change in Odds that

Client Will Graduate

If client is male 52% less likely

If client is married 2.92 times more likely

If client works full-time 4.34 times more likely

If client lives alone 69% less likely

Client has 2+ sanctions in first 30 days 56.2% less likely

Factors that don’t significantly

predict graduation from Drug Court:

Client age Client race

Primary Drug of Choice Prior Felony Convictions Prior Felony Drug Convictions Current Charge

Number of Sanctions Received Permanent Housing

3. Recidivism analysis for Drug Court clients and offenders who did not enter Drug Court

In this portion of the report, we describe analyses related to recidivism.

Although the Cowlitz County Drug Court provides assessment, education and treatment for drug offenders, the objective of the program is not merely

restricted to reducing future drug use or crimes specifically related to drugs. As a result, for this study recidivism is defined as a new felony arrest, and includes arrests for drug and non-drug felonies.

At a most basic level, one can simply identify the proportions of graduates, terminated clients, and offenders who did not enter the program that

received a new felony arrest. For Drug Court graduates, we count any felony arrest that may have occurred after graduation from the program. For

terminated clients, we look for any felony arrest that occurred after the client was terminated, and after any period of incarceration the client may have served to satisfy the original conviction(s). For offenders who declined to enter Drug Court, we consider any felony arrest that occurred after the date the offender refused the program, and after any period of incarceration the offender may have served to satisfy the original conviction(s).

Our analysis shows that 14.5% of Drug Court graduates received a new felony arrest after they successfully completed the program. This compares to a recidivism rate of 38% for clients who entered but did not graduate from the program, and 43.1% for offenders who did not enter the program. However, these data may be somewhat misleading, because not all groups had the same amount of time in which they could be arrested for a new crime. All else being equal, the more time that an offender is observed, the greater the

probability that a new arrest will occur. Clients terminated from Drug Court had a longer time to get arrested than graduates did because non-graduates tended to leave the program earlier. Moreover, offenders who did not enter Drug Court tended to serve a short period of time in jail or prison (if at all) after their decision not to participate, and thus they had an even greater amount of time in which a new arrest could occur.

One way to account for this problem is through the statistical procedure known as survival analysis (described above). In essence, survival analysis allows us to examine the probability that offenders will receive a new felony arrest over a specified period of time. Clients and offenders are “observed” only as long as they have been free to receive a new felony arrest, and these data are used to compute the probability of a new felony arrest during that time.

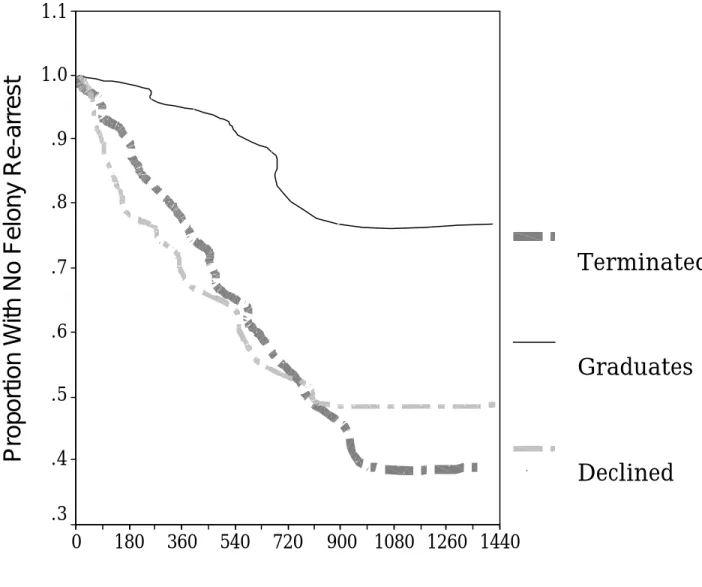

Figure 2: Survival Time to First Felony Arrest: Statistics for Clients Who Did/Did Not Enter Drug Court

Figure 2 provides results of a survival analysis that calculates the probability of a new felony arrest for Drug Court graduates, clients terminated from the program, and offenders who declined to participate in Drug Court. The data show that Drug Court graduates were significantly less likely than

terminated clients or offenders not in the Drug Court program to receive a new felony arrest within one, two, or three years of release from the program. A look at Figure 2 shows that over 90% of Drug Court graduates remained

Days Until Felony Re-arrest

1440 1260

1080 900

720 540

360 180

0

Proportion With No Felony Re-arrest

1.1 1.0 .9 .8 .7 .6 .5 .4 .3

Terminated

Graduates

felony arrest-free approximately one year after they left the program. This compares to a one-year survival rate of less than 80% for clients who were terminated from the program. (For offenders who did not participate in Drug Court, more than 30% received a felony arrest within the first year of their refusal to enter the program.) And at the end of three years, almost double the proportion of Drug Court graduates had avoided a new felony arrest, compared to the terminated and declined comparison groups.

We have previously seen that in most respects the characteristics of Drug Court participants and non-participants were similarly distributed. There are also relatively few characteristics that appear to distinguish Drug Court graduates from clients who didn’t complete the program. However, the three groups are not identically constituted, and it is possible that the reason graduates have a more favorable recidivism record than the other groups is because they are different in some respects that are unrelated to the Drug Court program. To consider this possibility, we perform a logistic regression statistical procedure. Just as our earlier model that examined factors that predict graduation from Drug Court, we consider whether these variables predict whether subjects would receive a new felony arrest. Our results are summarized in Table 10. (The full results of the procedure and all statistical tests are included in Section H of this document.)

Our results showed that, overall, the odds that an offender would receive a new felony arrest were a little more than 40%. However, we did confirm that there were statistically significant differences between graduates, terminated clients, and offenders who did not participate in the program. Indeed,

controlling for other factors, offenders who did not opt in to Drug Court were found to be over 5.5 times more likely to receive a new felony arrest,

compared to Drug Court graduates. Moreover, clients who failed to complete the program were almost 4 times more likely to receive a new felony arrest. We also discovered other factors that were associated with recidivism.

Offenders who had at least one prior drug-related felony conviction were 2.15 times more likely to receive a new felony arrest, controlling for other factors. In addition, we observed that clients who received 4+ sanctions during the

Table 10: Odds of New Felony Arrest: Graduates, Terminated Clients & Offenders Who Declined Drug Court

Overall odds of a New Felony Arrest

(N=255; Does not include active clients in Sept. 2003)

41.2%

Characteristic: Change in Odds For New

Felony Arrest:

Client declined Drug Court

(compared to Drug Court Graduates)

4.93 times more likely

Client failed to complete Drug Court

(compared to Drug Court Graduates)

3.01 times more likely

Each additional prior felony drug conviction 2.15 times more likely

Client received 4+ sanctions in first 60 days

(excludes non-participants)

2.73 times more likely

Factors that don’t significantly predict new felony arrest:

Client Age Client Race Client Gender

Primary Drug of Choice

Prior Felony Convictions (any type) Current Charge

Marital Status Employment Status

Total Number of Sanctions in Drug Court

first 60 days of entering Drug Court were 2.73 times more likely to receive a new felony arrest, compared to other Drug Court clients. On the other hand, several other factors were shown to have no significant association with recidivism. For example, the total number of sanctions a client received, and

the prior number of felony convictions (whether or not they were drug

felonies) did not predict re-arrest, nor did the available demographic or drug use variables.

F.

IMPLICATIONS OF FINDINGS

This section analyzes the main findings from this evaluation of the Cowlitz County Drug Court. The findings presented in this report should be

interpreted with caution for several reasons. First, all program evaluations have limitations. Some of the limitations of this particular project can be observed in most of the research on drug courts conducted nationwide (Belenko, 2001). For example, this study was unable to randomly assign participants to an experimental or control group. In addition, regional variation in population characteristics and drug abuse patterns make it difficult to compare results from this study with drug courts operating in different jurisdictions. Small sample sizes and missing data further

complicate efforts to generalize findings from particular programs. Therefore, comparisons of findings from this evaluation to other studies should be

undertaken with caution.

Nevertheless, the study has numerous strengths that do allow some conclusions to be drawn. We did have access to a sample of offenders who were deemed eligible to participate in drug court but declined to participate. These individuals were processed through the traditional criminal justice system. Thus, we were able to compare graduates and non-graduates who entered Drug Court with a pool of offenders who met the eligibility criteria but declined to participate. Although not as rigorous a study design as a classic experimental design, this study represents a significant improvement over many evaluations that merely look for differences among drug court participants. The data presented in this study reveal a great deal of information about the impact of the Cowlitz County Drug Court on this sample of offenders, in this jurisdiction. This study also provides evidence about a crucial aspect of drug courts—sanctioning activity—which has not received sufficient attention in previous research. As such, this investigation can be used to inform future studies on drug courts in other jurisdictions. Finally, one advantage of evaluation research is that it can highlight opportunities to improve program performance in the future.

The remainder of this discussion is broken into two parts. First, we highlight some of the key findings of the research. Second, we offer some specific

recommendations relating to data collection and client evaluation that may help to further improve what has been demonstrated to be an effective program.

1. Key Findings

The Cowlitz County Drug Court represents an important alternative to the traditional criminal justice approach for handling alcohol and drug-using offenders.

In 1989 the nation’s first drug court was established in Dade County, Florida (Aos & Barnoski, 2003; Burdon, Roll, Prendergast & Rawson, 2001;

Goldkamp, 2003). Since then the criminal justice system has witnessed a dramatic increase in the development of drug courts across the nation (Aos & Barnoski, 2003; Belenko, 2001; Brewster, 2001; Burdon et al. 2003;

Goldkamp, 2003). Accounts in the literature regarding the number of drug courts vary, but it appears that by the end of 2002 nearly 1,000 courts were in operation with another 400 or so in planning stages in all 50 states (Aos & Barnoski, 2003; Belenko, 2001; Brewster, 2001; Burdon et al. 2001; Harrell, 2003; Listwan, Koetzle-Shaffer, & Latessa, 2002). Drug courts vary both in terms of the services offered and the outcomes they produce (Belenko, 2001; Listwan et al. 2002; Sechrest & Shicor, 2001; Spohn et al. 2001; Wolfe, Guydish & Termondt, 2002), but they share similar goals of reducing future drug abuse and crime.

The primary rationale for the development of drug courts was to counter some of the unintended consequences of the “War on Drugs,” including increased demand of resources on the judicial system, jail overcrowding and the increased cost of the “revolving door” related to drug crime (Brewster, 2001; Cox, Brown, Morgan & Hansten, 2001). In addition, the criminal justice system experienced somewhat of a paradigm shift from crime control and deterrence-based approaches to “problem-solving” solutions focusing on

rehabilitation (Goldkamp, White & Robinson, 2001; Harrell, 2003; Longshore, Turner, Wenzel & Morral, 2001).

Drug courts do not exclusively focus on punishment for the offense; rather they integrate the crime control and rehabilitation objectives. Sechrest and Shicor (2001) note that drug courts focus on the potential cause of the crimes (i.e. addiction) and other social and environmental issues, but at the same time hold the offender accountable for his/her behavior with the use of sanctions. In a drug court program, the offender has the opportunity to participate in drug treatment with judicial oversight. In other words, the Cowlitz County Drug Court is used as a lever to get people into treatment to keep them engaged in treatment.

For alcohol and drug offenders, the Cowlitz County Drug Court is more effective at reducing future criminal behavior than the traditional criminal justice process.

Belenko has conducted reviews of existing research on drug courts (1998, 1999, 2001) and found reduced arrests and/or convictions in outcome

evaluations. Other studies not included in Belenko’s 2001 compilation have found similar successes regarding recidivism (Aos, 1999; Cox et al. 2001; Goldkamp et al. 2001; Harrell, 2003; Listwan et al. 2002; Miller & Shutt, 2001; Peters & Murrin, 2000). One outcome evaluation found an increase in recidivism for drug court participants ( Miethe et al. 2000;) and a few have been unable to document an effect of drug courts on recidivism (Aos & Barnoski, 2003; Listwan, Sundt, Holsinger & Latessa, 2003; Wolfe et al., 2002).

The results from the present study are consistent with the vast majority of previous investigations about the ability of drug courts to reduce criminal behavior. By the end of three years, the rate of recidivism (measured as a new felony arrest) for Cowlitz County Drug Court graduates is about half of that observed for offenders who did not participate in Drug Court and were instead adjudicated in the traditional criminal justice system. Graduates also fared considerably better than clients who failed to complete the program.

The fact that this study tracks offenders and former Drug Court clients for as long as four years indicates that the Drug Court program has a long-term effect on reducing criminal behavior among the drug and alcohol abusing population.

Client behavior in the early days and weeks of Drug Court predict successful program completion and lower recidivism

We discovered that 44.4% of offenders admitted to the Cowlitz County Drug Court eventually graduated from the program. The graduation rate observed in this study is consistent with data that has been collected from other drug court evaluations. Belenko (2001) conducted a review of 37 published and unpublished evaluations of drug courts across the nation, and discovered that about 47% of clients admitted to drug courts across the US eventually

graduate. Barnoski and Aos (2003), in a review of six Washington State drug court programs, observed graduation rates that ranged from 26% to 58%. One of the more interesting findings of this evaluation is that, holding constant other possible risk factors, the behavior of clients in the early days and weeks after admission to Drug Court is a powerful predictor in

determining whether they will eventually complete the program. We discovered that although Drug Court graduates received slightly fewer

sanctions (on average) than clients eventually terminated from the program, both groups tended to receive a significant number of sanctions. The more salient issue was whether a client received sanctions early in the program. Indeed, in a regression model predicting whether a client would graduate, the number of sanctions the client received was not a significant predictor, but if the client received 2 or more sanctions in the first 30 days of the program, the probability of graduation dropped by almost one-half.

2. Recommendations

One positive benefit of evaluation research is that it can identify ways in which programs may be improved. Many of the following recommendations relate to the maintenance of the Drug Court database. We believe that

changes in the structure of the database, and modification in data collection and entry procedures can increase the ability of the Drug Court team not only to evaluate the progress of individual clients but also to make continual

appraisals of the program. Based on our analysis of program outcomes, we also offer recommendations concerning how clients are assessed at intake and throughout the program.

Redesign the Drug Court database

The Cowlitz County Drug Court uses a Microsoft Access database to store information about all offenders associated with the program, from the time offenders are initially evaluated until their graduation or termination. The database is potentially a rich source of information not only for keeping track of a particular client’s progress, but also to provide aggregate data about all program participants. However, our review of the database structure

revealed several flaws that limit the ability of the database to provide the Drug Court team with information that can help to efficiently manage the program. Rather than provide an extensive list here, we highlight a few changes that might be considered.

For one thing, many of the database fields have not been designed to prevent null values from being entered. As a result, data fields for many offenders and clients have been left blank, leading to missing data. As we have noted elsewhere, a substantial number of offenders and clients had missing data for important demographic, residential, employment, and drug history variables, making it more difficult to investigate how these factors might be related to program effectiveness.

Second, when the Drug Court database was initially designed, many of the data structures that were created to record changes in client status were text fields. These fields allow members of the Drug Court team to make detailed notes about the status of the offender when new information was available. However, the Drug Court database should also be modified to include more categorical measures of offender progress (e.g., a ranking of client attitude toward treatment, on a scale from 1 [very negative] to 5 [very positive]).

Categorical variables would allow the Drug Court team to instantly generate summary measures about the progress and status of all clients.

Third, some of the data fields are constructed so that when an offender’s particular status is updated in the database, the previous data are deleted. For example, clients can be promoted or demoted between several phases during their participation in Drug Court. However, as the database is currently constructed, summary information about the client’s status is deleted when new information is recorded. (Of course, the data may exist if a Drug Court team member enters it in a text field, but it is exceedingly

difficult to efficiently extract this kind of data for multiple clients.) To

consider how useful this client history can be, it is instructive to consider our results that showed Drug Court graduates stay sanction-free for longer periods of time than terminated clients, but graduates still earn a similar number of sanctions. It is possible that a spike in sanctions occurs at about the time clients are promoted to a less-restrictive phase of the program. If data are overwritten, however, this possibility cannot be explored.

A related problem, mentioned earlier in this report, is that many of the clients’ characteristics that may change during their participation in the program is often not updated in the database. For example, client residence and living arrangements are recorded when an offender enters the program, but subsequent changes are not reflected in the database.

Ensure complete data collection for all offenders considered for Drug Court, even if they ultimately decline to opt in.

As we have noted elsewhere, a large number of offenders who were initially considered for Drug Court but declined to participate had missing data. For ongoing program review, it is important to have complete data on these subjects to compare them to Drug Court clients.

Incorporate data from pre-docket meetings into the Drug Court database

Members of the Drug Court team generate some of the most potentially important information about a client’s progress in Drug Court during weekly pre-docket meetings. These meetings typically include the Superior Court Judge, the Drug Court Coordinator and other members of the Corrections Department, and representatives from the drug and alcohol treatment providers. Before clients are scheduled to appear in court, the Drug Court team reviews all aspects of a client’s progress in the program and makes recommendations to the Judge. At the present time, a member of the Drug Court Team can enter a brief summary of the discussion into the database. We recommend developing a set of summary measures about each client that are made at the pre-docket meetings. For example, variables should be

developed that capture the Drug Team’s assessment of the client’s attitude in treatment, or their efforts to secure and maintain employment. The data should be recorded in the database in a way (e.g., 1-5; Very Unsatisfactory to Very Satisfactory) that will facilitate additional aggregate-level analyses. These data may illuminate additional ways in which the Drug Court team could improve program outcomes.

Conduct a rigorous review of each client after 30 days, paying

particular attention to the number of sanctions they received during this critical period.

One of the more interesting findings of this evaluation is the fact that a client’s behavior in the first few weeks of Drug Court is a powerful predictor of whether they will ultimately graduate from the program. We suggest that the Drug Court team conduct a rigorous review of each client 30 days after they begin the program. However, we do not recommend that clients should be summarily terminated from the program if they have several early sanctions. Although we discovered that clients who had 2 or more sanctions within the first 30 days were at significantly greater risk of not graduating, about 1 in 3 of these clients did eventually graduate. Rather, we suggest that the Drug Court team recognize that offenders with several early sanctions