§nanking Practices Among Mothers of Children Aged 0-2 Years

By

Thomas Walker Robinson

A Master's Paper submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial

fulfilhnent of the requirements for the degree of Master of Public Health in the Public Health

Leadership Program.

Chapel Hill

ABSTRACT

Objectives. To describe and compare spanking rates among a representative sample of North

Carolina mothers of 0-2 year old children.

Patients and Methods. A cross-sectional anonymous phone survey of mothers of children less

than 2living in North Carolina in 2007. Spanking (with open hand on the buttocks) occurrence

was assessed among all respondents. Multivariate logistic regression was used to examine the

association between spanking and specific maternal and child characteristics.

Results. The occurrence rate of spanking, in a state-wide sample of children less than 2 years of

age, among all maternal respondents was 30.8% (unweighted, 29.1%). Predictors of spanking

included increasing age of the child, decreased maternal age, non-Hispanic ethnicity, and

decreased family income. With every advancing month of age, a child had 20% increased odds

of being spanked. Mothers aged 14-20 had 2.32 times the odds of spanking than mothers aged

36 and older. Mothers aged 21-35 had 1.50 times the odds of spanking than older mothers.

Hispanic mothers had 0.48 times the odds of spanking compared with white or black mothers.

Families earning between $40,000-80,000 had 1.52 times the odds of spanking their child

compared with families earning greater than $80,000.

Conclusions. Many North Carolina mothers admit to spanking their very young children,

sometimes before their child reaches 6 months of age. The AAP should urge pediatricians to

begin their discussions about discipline during the 2 and 4- month well-child visits, continuing

the discussion at subsequent visits. Increased focus should be given to young mothers and those

in lower-to-middle income brackets. Media and legislative efforts may also be needed to meet

INTRODUCTION

Corporal punishment, especially the fine line between discipline and physical abuse, is a

controversial topic among doctors and patients alike. Notwithstanding the controversy, recent

US studies have reported that 70- 95% of children were spanked in the previous year.1' 2

Studies over the last decade reveal that 29 - 77% of parents admitted to spanking their children

before the age of 2.2·7 Regalado et al. noted that 6% of mothers responding to a survey reported

spanking their 4- 9 month old child "sometimes" or "rarely"7 No studies to date have specifically measured month-by-month patterns of spanking during the early developmental

period, nor have studies been conducted to characterize subsets of mothers who are most likely

to be early spankers.

In 1998, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that parents be encouraged

and assisted in the development of methods other than spanking for managing undesired

behavior.8 Two years earlier, in 1996, the AAP convened a panel which developed

recommendations against all physical punishment for children under age 2. 6 These

recommendations appear to initiate this discussion too late; pediatricians are not advised by the

AAP to begin discussions with parents about discipline until the 9-month well-child visit.9 Parents may be initiating their own disciplinary practices before that discussion is started.

The consequences of early spanking on the future development of the child attest to the

significance ofthis issue. Bugental et al. noted that infants who receive frequent physical

discipline showed high hormonal reactivity to stress and an altered

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which they note may increase the child's risk of sensitization to later stress,

meta-analyses posit an association between parental spanking and negative child outcomes such as

aggressiveness, anti-social behavior, psychological problems, and future delinquency.11.16

We conducted a serial cross-sectional analysis of parental spanking of children under the

age of 2 among mothers participating in a larger study examining discipline and shaking

practices among North Carolina parents. Mothers were surveyed about their own disciplinary

practices as well as the disciplinary practices of spouses or partners involved in the child's

upbringing. Spanking, for the purposes of this study, is defined as being hit on the buttocks with

the hand only. Our goal was to describe the pattern of use of spanking by parents as a

punishment approach to misbehavior in very young children. We also sought to examine trends

in the use of corporal punishment by comparing incidence rates to a similar 2002 study of

parental disciplinary practices in NC and SC.17 A secondary goal was to determine whether rates

of early spanking are significantly different among mothers with differing demographic profiles.

We hypothesized that mothers most likely to spank their very young children will be those most

stressed during the early months of the child's life, namely single mothers and mothers with low

socioeconomic status.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Participants: The NC Center for Health Statistics provided 28,751 names and addresses of

children below age 2. This sample was obtained from birth certificate data using a random

sample of children born between October 1, 2005 and July 31,2007. The names and addresses

of parents were sent to a survey research vendor (Genesys Sampling Systems, Fort Washington,

PA). This vendor searched publicly available databases for phone numbers that were then used

of the North Carolina population, including comparable proportions of minority groups including

African American, Hispanic, and Native American women.

Interviewers were trained by the investigators and the director of the UNC Survey

Research Unit at the start of the survey. All participants were offered "debriefing" regarding

concerns about child discipline or the answers that they gave by providing an 800 number for

Prevent Child Abuse North Carolina. They were also given an 800 number to call one of the

authors (DR) if they would like to debrief with him or his staff regarding any concerns triggered

by the survey. All study procedures were approved by and complied with policies of the

Institutional Review Boards at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and Duke

University.

Survey Design: We conducted a probability-based telephone survey between October 2007 and

April2008 of households in North Carolina to ask about the parenting behaviors of parents of

children under the age of 2. The instrument elicited the frequency of specific child disciplinary

behaviors used by parents. To standardize the questions and sample, we surveyed mothers who

were living in the home with one or more children below the age of 2.

Our sampling protocol called for up to 12 calls, at differing hours of the day and days of

the week, before a number was dropped. Approximately 10% of randomly selected calls were

monitored for quality control. The 25-minute interview was entered into BLAISE, a computer

administered interview system, by the Survey Research Unit of the UNC Department of

Biostatistics. The survey was administered anonymously, with deletion of phone numbers

immediately after assessment of inclusion criteria, and was conducted in either Spanish or

Outcomes and other measures: Parents were administered the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics

Scale18· 19, a validated instrument designed to collect disciplinary behaviors. This instrument

covers a range of parent discipline practices from "time out" to yelling, spanking, shaking, and

choking. Respondents are asked to respond how many times they have used each practice in the

last year, from none to more than 20 times. Then, if the answer is "not in the past year," they are

asked if they have ever used this tactic. Additional questions include family composition,

employment, ethnicity, and religion so that the data can be weighted to provide population

estimates for the state. Mothers were asked to respond separately for themselves and for their

husbands or partners about what each has done for discipline.

Statistical Analysis: All analysis used estimates weighted by socioeconomic status and

race/ethnicity, in order to be representative of the NC population. Spanking frequencies were

determined for each month-long age category, for a total of22 categories between 3 and 24

months. Mothers were dichotomized as spankers or non-spankers of the index child to examine

variations in maternal discipline according to selected parental and demographic characteristics

one at a time. These included maternal age, marital status, educational level, ethnicity, family

income, as well as age and sex of the child. Survey-weighted bivariate logistic regression

analyses were conducted initially for each independent variable separately. Survey-weighted

multiple logistic regression was then used to examine the potential associations between

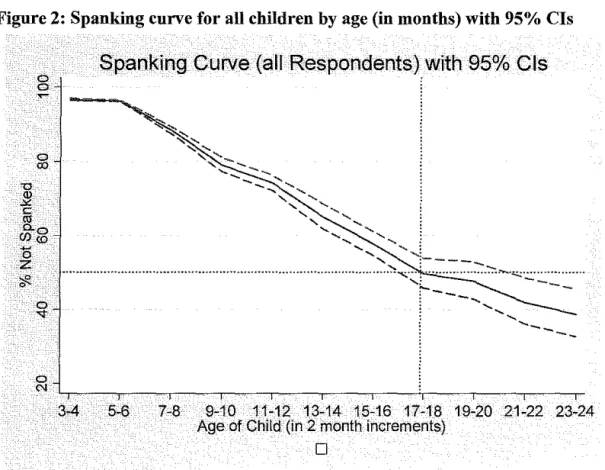

spanking and these parental and demographic characteristics. Resembling Kaplan-Meier

survival curves, spanking curves were created plotting percent not spanked among each month

cohort of children in order to represent visually the likelihood of spanking in a hypothetical NC

child over time. Spanking "curves" were created for all maternal respondents as well as for

children were spanked was used to compare, with a single statistic, the occurrence of spanking

among the children of different subsets of mothers. Analysis was conducted using Stata version

10.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Subject Characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics for the 2790 maternal respondents are presented in

Tables 1 and 2. Table 1 reports both unweighted and weighted maternal and family

characteristics of all respondents, while Table 2 separates the maternal respondents into those

who had and had not spanked the index child. The majority of mothers surveyed were living

with a spouse/partner, college-educated, middle to high income, and were of Caucasian ethnicity.

More than 99% of respondents were the biological mother of the index child. The index children

in this study were all between 3 and 24 months of age, and there were roughly equal numbers of

boys and girls.

Spanking Occurrence Rate

Out of the 2790 mothers surveyed, 813 (or 29 .I%) admitted to spanking their child in the

past year, corresponding to a weighted NC prevalence of30.8%. This is in comparison to the

30.0% prevalence of spanking of 0-2 year olds in the previous 2002 survey ofNC and SC

mothers (n = 115).17 Frequency of spanking in the past year was assessed, and is graphically represented in Figure I. Notably, 3.1% of all mothers-and 10.7% of those who had spanked

their index child-responded that they had spanked their child more than 20 times in the past

Maternal and Family Characteristics Predicting Spanking

Modeling was undertaken to examine the relationships between respondents of differing

demographic characteristics and the use of spanking as a disciplinary method. Three maternal

characteristics predicted spanking in our final multivariable logistic regression model (see Table

2). Spanking occurrence was inversely associated with maternal age. Mothers younger than age

20 had 2.32 times the odds of spanking their child as mothers older than age 36 (p = 0.001 ),

while mothers aged 21 - 35 had 1.50 times the odds of spanking their child as older mothers (p =

0.008). There was a significant, though complex, relationship between spanking occurrence and

maternal ethnicity. While mothers of varying ethnicities were surveyed and included in the

overall analysis, numbers of Asian, Native American, and other ethnic groups were so low that

they were excluded from specific stratified analyses. There were no significant differences in

spanking between white and black mothers, although Hispanic mothers had roughly half the odds

of spanking their child compared to their white and black counterparts (OR= 0.48; p = 0.001 ).

Finally, family income was a marginal predictor of spanking occurrence among maternal

respondents. Mothers earning $40,000-80,000 had 1.52 times the odds of spanking their child as

mothers earning greater than $80,000 (p = 0.001). Those mothers earning less than $40,000

spanked their child at levels no different than mothers earning greater than $80,000 (p = 0.082).

Marital status and maternal education were not significantly associated with maternal spanking

in our study (p > 0.05, in both cases).

As expected, there was a highly significant direct relationship between child's age and

increasing month of life (p < 0.001). Mothers of boys had no higher odds of spanking than

mothers of girls.

Spanking Curves

Figure 2 shows the spanking curve of all maternal respondents with 95% confidence

intervals. The age at which a 50% spanking rate was reached among all mothers was 17.4

months. Half ofNC children, we conclude, will be spanked by the age of roughly 17 months.

Among mothers of the three age levels (age 14-20,21-35, and 36-49), the 50% spanking rate was

reached at 14.6 months, 17.1 months, and 18.6 months, respectively. Among white and black

mothers, the 50% spanking rate was reached at 17.6 months and 14.7 months, respectively, while

Hispanic mothers never crossed the 50% spanking threshold. Finally, the 50% spanking level

was reached at 17.6 months, 15.7 months, and 18.6 months in mothers making less than $40,000,

between $40,000-80,000, and greater than $80,000, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicated that the spanking of children under the age of two is quite common

among parents in North Carolina. Almost one-third of mothers (30.8%) of young children

admitted to spanking their child in the past year, some more than twenty times. This overall

occurrence rate is very similar to the values found by Slade et al.3 (38.7% in a nationally representative sample) and Socolar et al.4 (29% among a NC sample), as well as a similar 2002

study of North and South Carolina maternal discipline practices in children 0 to 2 years of age

(30.0% among a small sample (n=l15))17. Unlike these three studies, however, our survey

logistic regression showed significant spanking differences between mothers of different ages,

ethnicities, and income levels, findings also reinforced by the 50% spanking values calculated

from the spanking "curves". Interestingly, our hypothesis that spanking occurrence would be

partially explained by marital status was not supported, as marital status was not a significant

predictor of spanking in our study.

Much of the spanking literature has sought to ascertain a relationship between parental

demographics and spanking across the entire pediatric age spectrum, while this study focuses

specifically on the spanking of very young children. Our study supports the strong evidence in

the literature that spanking occurrence is inversely related to increased maternal age. 6• 7• II. 20• 2I It

is perhaps not surprising that younger, less experienced mothers are more likely to resort to

spanking in their discipline strategies. Challenging much of the literature associating black

hn. . . h high nk' I 2 6 7 II 20 22·25 " d d'f" b h

et lCity Wit er spa mg preva ence · · · · ' , we 10un no I 1erence etween t e

spanking practices of black and white mothers. This is one of the first studies of spanking

practices to include a significant number of Hispanic mothers, a group who, according to our

findings, spank their children significantly less than either black or white mothers.

Our hypothesis that family income, the most often utilized measure for socioeconomic

status, would be a highly significant predictor of maternal spanking was confirmed, although not

in a purely linear fashion. The scientific literature on this relationship has been equivocal; seven

studies have found a direct relationship between decreased income and increased spanking

practices. 2• 6• 7• II, 22• 23• 26 Three other studies found no relationship between income and spanking

prevalence20•24•27, while another found equivocal results.4 In our study, mothers at the lowest

end of the economic spectrum(< $40,000 I yr.) were not more likely to spank than wealthier

spank than those making more than $80,000 per year. Perhaps mothers with very low incomes

are, due to financial difficulties, living with other more experienced family members who are

less likely to advocate spanking during the early years of parenting.

Despite past studies associating differential spanking prevalence with maternal marital

1 11 26 d d . I . 11 2o-22 2s · h h · · · 'fi I d' d status ' · an e ucatwna attamment · ' , ne1t er c aractenstlc s1gm 1cant y pre Jete

spanking in our study. Nor did our study find, as did several others6• 11·20•23•26, that the sex of the

child predicted spanking prevalence. As expected, most prevalence studies have shown an

inverse relationship between child age and spanking prevalence throughout the early childhood

years 7· 20• 27, a finding also supported by our study.

This study suggests that the 1996 American Academy of Pediatrics panel conclusions that

children under the age of 2 should not be spanked and the 1998 AAP encouragement against

spanking as a primary disciplinary practice, particularly in children under 18 months of age, are

not being followed. One explanation is that pediatricians begin discussing disciplinary methods

too late in the parenting process. In Bright Futures, the AAP's Guidelines for Health

Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, discipline is first mentioned during the

nine-month visit, at which point pediatricians are advised to discuss parenting expectations,

consistency, behavior management, and cultural beliefs about child-rearing.28 We note that 7.9% of parents of children aged 3 - 9 months already admit to spanking their child, well before the

AAP suggests that discipline tactics should be discussed in a well-child visit. As for the older

children in our sample (9-24 month olds), it could be that pediatricians are not addressing

issues of parental discipline in the periodic well-child visits, while it also may be that their

advice is not being heeded as other cultural forces regarding spanking may be operating. We

as the two or four month visit, particularly with younger mothers and those in lower-to-middle

income brackets. Each visit thereafter should seek to assess the success of current discipline

strategies, reinforcing those practices other than spanking. Public health interventions such as

media coverage and legislative efforts may also shift the early spanking practices of the public.

Further research continues to be needed in the area of parental discipline. Other large

scale spanking prevalence studies are needed to confirm the high levels of spanking of very

young children found in our study. The studies attempting to link early spanking to later

outcomes such as aggression or antisocial behavior are fraught with methodological

complications, but efforts to show a causative connection between spanking and later negative

outcomes need to be undertaken while controlling for other discipline styles and practices.

Underlying the entire discussion of parental discipline, more research is needed comparing the

efficacy of spanking to other disciplinary alternatives. Without solid scientific studies showing

increased efficacy and better long-term outcomes, pediatricians will continue to have difficulty

persuading themselves and the families of their patients that spanking should be discouraged.

There were a number of limitations to this study. First, this is a survey of mothers in the

state of North Carolina and may not, therefore, be representative of mothers across the United

States. Earlier national studies noted higher rates of spanking in the southeastern US2• 26;

therefore rates may be lower in other regions. Second, while respondents described their spouse

or partner's discipline practices, we did not specifically ask spouses or partners about such

practices. Third, given the cross-sectional nature of the data, any attempt to prove causality

between spanking prevalence and predictive demographic characteristics is unwarranted. Fourth,

our phone survey included very few cell phone users, limiting the generalizability of our

Finally, self-reported disciplinary practices are likely to be underestimations of actual prevalence

due to the social stigma against admitting the use of parental corporal punishment to an unknown

surveyor.

Virtually all pediatricians agree that children below the age of 2 should not be spanked.

Notwithstanding this consensus, almost one-third of mothers in our survey admitted to spanking

their infant on the buttocks by their second birthday. As noted above, this is likely an

underestimate of actual spanking practices. Not all mothers, however, are equally likely to spank

their infant. This study suggests that younger maternal age, non-Hispanic ethnicity, and

lower-to-middle family incomes are predictive of higher levels of spanking before the age of2. Such

predictive characteristics should aid pediatricians in developing a wider range of discipline

advice catered to the particular mother-child pair during periodic clinic visits. The goal of such

interventions is not to ostracize mothers who seem more likely to spank their infants; rather, the

goal is to provide support, offer alternatives, and ultimately prevent what in some cases may

Appendix 1: ADDENDUM TO INTRODUCTION

Historical Background on Spanking

Prior to the middle of the twentieth century, Western views on corporal punishment and

spanking were most often taken directly from religious and moral sources, particularly the Bible.

According to the book of Proverbs chapter 22, "Foolishness is bound in the heart of a child; but

the rod of correction shall drive it far from him." ( v. 15) One chapter later, the author of

Proverbs notes, "Withhold not correction from the child: for if thou beatest him with the rod, he

shall not die. Thou shalt beat him with the rod, and shalt deliver his soul from hell." (vv. 13-14)

Child-rearing manuals and letters from the 17th through early 19th centuries stressed the

importance of "breaking the will" of the child through corporal punishment. According to the

17th century philosopher John Locke, "Those therefore that intend ever to govern their children,

should begin it whilst they are very little; and look that they perfectly comply with the will of

their parents."29 Further building this argument for physical discipline, he continues that "liberty

and indulgence can do no good to children; their want of judgment makes them stand in need of

restraint and discipline. "29

Such disciplinary practices were not limited to children, but were also used in

disciplining infants. Susanna Wesley, mother of the 18th century founder of Methodism John

Wesley, was quite explicit in her discussion of infant physical discipline. In an autobiographical

letter to her grown son, she notes that "[ w ]hen [my children] turned a year old (and some before)

they were taught to fear the rod and to cry softly, by which means they escaped abundance of

correction which they might otherwise have had: and that most odious noise of the crying of

children was rarely heard in the house, but the family usually lived in as much quietness as if

Esther Edwards Burr, wife of Vice President Aaron Burr, utilized similar practices in the

upbringing of her children. Reporting to her friend Sarah Prince the manner in which she was

raising her first-born daughter, Burr notes "I have begun to govourn (sic) Sally ... She has been

Whip' d once .. and she know the differance (sic) betwen (sic) a smile and a frown as well as I

do."30 Later in this same letter we find out that young Sally is "not quite Ten months old."30

There were dissenting voices regarding corporal punishment during the 17'h and 18th

centuries. Cotton Mather, one of the leading preachers in early 18th century New England, had a

very different-and surprisingly modern-perspective on childhood discipline. When one of his

children misbehaved, he first "lett [sic] the Child see and hear me in Astonishment, and hardly

able to beleeve (sic) that the Child could do so base a Thing."29 Discussing more specifically the

use of the rod, he continued, "I would never come, to give a child a Blow; except in Case of

Obstinacy; or some gross Enormity."29 Almost a century later, John Witherspoon, New Jersey

Presbyterian minister and subsequently President of Princeton College (later University), echoed

Mather's comments, noting that a "parent that has once obtained, and knows how to preserve

authority, will do more by a look of displeasure, than another by the most passionate words, and

even blows."29

By the middle of the 19th century, these dissenting voices were becoming more

numerous. This is not to say that there was a dramatic shift in the disciplinary practices of most

American families. Such a change was not to occur until the second half of the 20th century. But

with the dissemination of the ideas of the European and American Romantic movements (as

exemplified in the writings of Rousseau) stressing the inherent innocence of childhood, as well

as the Transcendentalist antipathy to authoritarian rule, some parents of the time were persuaded

while "a reign of brute force is much more easily maintained," it is actually a "reign whose

power is righteousness and love" which ultimately leads to a "truly good and sanctified life."29

"So much easier is it to be violent than to be holy," he continues, "they substitute force for

goodness and grace, and are wholly unconscious ofthe imposture. "29

Advances in the fields of psychology, social work, and other social sciences in the early

20th century brought about a more "scientific" view of childhood, and with it changing views on

corporal punishment. Heavily influenced by the work of G. Stanley Hall, these scientists sought

to study child development within a more "empirical" framework than before. 31 It is clear that by the middle of the 20th century, two conflicting child-rearing styles had emerged, the

"authoritarian" (emphasizing 'breaking the will' of the child) and the "permissive" (emphasizing

nurturing of the child's character), setting the stage for what Baumrind calls the 'discipline

Appendix 2: Background on the Spanking Controversy

Raging Debate in the Popular Press

Throughout the second half of the 20'h century and well into the 21st century, spanking

has been a hot topic of discussion among the general public. Often the debate is split along

political lines, with conservatives more often than not advocating spanking, and liberals more

likely to be against physical punishment. Most people's beliefs fall on one side ofthe debate or

the other, and few see their positions as mutable. In most cases, in fact, parents discipline their

children in the same way that they themselves were disciplined as a child.

Much of the popular pro-spanking rhetoric centers around the centuries-old Biblical

sanction of physical punishment as a way to "break the will of the child" (see discussion above).

Conservative Christian writers, most notably Charles Dobson, whose book Dare to Discipline

sold more than 2 million copies in the 1970s, carry the traditional, biblically-focused argument

for spanking to the contemporary public. Directly challenging the "unstructured permissiveness

we saw in the mid-twentieth century," Dobson argues that "spanking is the shortest and most

effective route to an attitude adjustment."33 Other spanking proponents, like popular

psychologist John Rosemond, argue that human beings are, by nature, inclined to selfish,

anti-social behavior, such that "proper anti-socialization requires a combination of powerful love and

equally powerful discipline. "34

Anti-spanking advocates argue first and foremost that violence begets violence.

Spanking one's child, they continue, may lead to decreased self-esteem and, even worse, future

anti-social behavior. "Corporal punishment," notes historian Philip Greven, "trains children to

popular works decrying the long-term detrimental effects of spanking on children and more

scholarly studies seeking to prove this same point. In concluding his book Beating the Devil Out

of Them, Straus argues that a "society that brings up children by caring, humane, and non-violent

methods is likely to be less violent, healthier, wealthier, and wiser," and that the elimination of

corporal punishment "will have profound and far reaching benefits for humanity."35

Debate among the Scientific Community

By the 1990s, a contentious debate had emerged within the pediatric literature as to the

effects of spanking on children, with one camp advocating spanking under certain conditions and

the other advocating the absolute prohibition of spanking. While couching their passionate

opinions on the practice within the more objective perspective of scientific studies, it was

nevertheless clear that neither side saw much to learn from the other.

Conditional-Spanking Gronp

The conditional-spanking group of scientists has generally sought to find a middle ground

between the unquestioned traditional acceptance of corporal punishment in Western culture and

the opposing views of those contemporaries who argue that there is never a legitimate reason to

spank a child. The leading voices in this group are Baumrind32 and Larzalere36, and their

argmnents are manifold.

First, they cite longitudinal research showing that there are no adverse effects of corporal

punishment in middle-class, intact families. Their consistent emphasis is that it is the marmer in

which discipline is administered that ultimately affects the child as opposed to the methods used.

They continue by arguing that corporal punishment administered in a warm family environment

with clear expectations can be an effective way to discipline children. Secondly, they cite

occurring as often as 3 to 15 times per hour.37 While reasoning with a child may indeed be

preferable to spanking in many cases, they argue that the sheer number of parent-child conflict

interactions will warrant spanking as an effective disciplinary practice at certain times. This ties

closely with a third argument from the conditional-spanking camp, that spanking is an effective

short-term deterrent in response to adverse behavior. They cite authors such as Roberts et al38,

showing that oppositional children can be effectively disciplined with spanking as a way to

enforce other discipline strategies like timeout.

Finally, they note that spanking should only be used in appropriate circumstances,

namely: in children 2 to 6 years old; never in infants or adolescents; with the intention of

correction and teaching; not out of anger, frustration, or the desire to hurt; and limited in

intensity to one or two strikes by an open hand applied to buttocks or thighs only.39

Anti-Spanking Group

The anti-spanking group argue that "corporal punishment is ineffective at best and

harmful at worst."12 Quite passionate in their cause, this group has been more vocal in the popular press, espousing their arguments for the end of all corporal punishment of children. One

of their prime arguments is that spanking can escalate into full-scale child abuse. They cite

studies which note that the majority of child abuse cases do not result in serious bodily harm, and

that they seem to be rooted in ideas of corporal punishment.40 Next they posit several

longitudinal studies showing that corporal punishment in childhood is associated with increased

psychopathology and violent behavior in later life.4145 A recent meta-analysis by Gershoff12 found that spanking frequency is positively related to aggression, misconduct, and related

constructs, though Benjet et al. counters that "it is nether surprising nor enlightening that more

Closely linked to this is the idea that spanking models violent behavior for children.

This, they continue, not only affects the children that are spanked, but also results in an increased

level of societal violence. Finally, they argue that, despite its ubiquity in Western society,

spanking has not been proven to be scientifically effective in managing adverse behavior. This is

a fairly difficult argument to challenge, given the overall lack of strong data on spanking

efficacy. Like the conditional-spanking group, they look to future research to help tease out the

continuing methodological details in assessing the short- and long-term effects of corporal

punishment on children.

Points of Agreement between the Two Camps

While the scientific debate on both sides of this issue can be quite heated, there are a

number of key points of agreement between the two groups. First, both groups argue that

spanking of infants should never be endorsed. This is particularly important in light of this

paper's focus. Regardless of the results found in our NC maternal survey, both groups would

likely respond that any spanking prevalence above zero is too high. Secondly, neither group

supports the use of spanking as a discipline strategy by itself. Finally, both groups agree that

Appendix 3: 1996 AAP Consensus Statement on Corporal Punishment

With evidence-based arguments on both sides of the spanking debate, the American

Academy of Pediatrics invited 23 participants (representing the fields of sociology, psychology,

and pediatrics) from both sides of the argument to a 2-day conference entitled "The Short and

Long of Corporal Punishment" in February 1996. The goal of this meeting was both to assess

the scientific evidence regarding the effects of corporal punishment on the pediatric population

as well as to develop a set of consensus statements on corporal punishment for Academy

pediatricians. While the participants made recommendations based on their own knowledge of

the scientific literature, no specific systematic review of the relevant literature was undertaken.

This account of the proceedings relies heavily on the summary provided by Bauman and

Freeman's 1998 coverage of the conference?9

Despite intense debate and significant disagreement among participants, thirteen

consensus statements were ultimately endorsed. For the purposes of these consensus statements,

spanking was defined as "physically noninjurious, intended to modify behavior, and

administered with an opened hand to the extremities or buttocks. "39 The 13 consensus statements are as follows:

1. Recommendations concerning the discipline of children should be based on a reasoned interpretation of currently available data regarding the short- and long-term effectiveness and consequences of differing parts of a system of discipline.

2. Any disciplinary technique, including spanking, should be endorsed only if research demonstrates that the short- and long-term benefits outweigh the short- and long-term harm to the child or the caregiver (parent).

3. Spanking a child should not be the primary or only response to a misbehavior used by a caregiver.

4. Escalation from spanking to abusive levels of punishment may occur when caregivers have uncontrolled anger. Spanking should be avoided under these circumstances because of the risk for significant injury.

6. There are no data bearing on the effectiveness of spanking to control misbehavior short term in the average family. Limited data in preschool children with behavior problems suggest that spanking may increase the effectiveness of less aversive disciplinary techniques. Data relative to the long-term consequences of spanking of preschool children are inconclusive.

7. Noncorporal methods of discipline of children have been shown to be effective in children of all ages, including reasoning, modeling, positive reinforcement of desired behaviors, and aversive consequences for misbehavior. Correct implementation of these procedures, especially time out, is important to their effectiveness. Family education and support have also been shown to help prevent behavior problems and should be

recommended.

8. Currently available data indicate that corporal punishment, as previously defined, when compared with other methods of punishment of older children and adolescents is not effective and is associated with increased risk for dysfunction and aggression later in life. 9. Corporal punishment is one of many risk factors for poor outcomes in children.

Characteristics of the child, parent, family, and community, including temperament, stress, and resources, may increase or decrease the risk.

10. Efforts aimed at reducing the use of corporal punishment through family, school, and community-wide programs should be culturally sensitive and coupled with efforts to teach the many alternative methods of discipline shown to be effective.

11. Findings relative to parental discipline are not applicable to the school setting. Data indicate that corporal punishment within the schools is not an effective technique for producing a sustained, desired behavioral change and is associated with the potential for harm, including physical injury, psychological trauma, and inhibition of school

participation.

12. Concerning forms of corporal punishment more severe than spanking in infants, toddlers, and adolescents, the data suggest that the risk for psychological or physical harm

outweigh any potential benefits.

13. Although sufficient data currently exist to allow for these consensus statements, and although much is known about effective disciplinary strategies, additional research is still needed to clarifY issues relative to optimal disciplinary approaches to children. These conclusions should be viewed as subject to revision and clarification as data continue to accumulate.

Most relevant to the current study is statement 5, condemning the practice of spanking of all

children under the age of two. Additionally, all forms of corporal punishment other than

spanking were unanimously described as unacceptable disciplinary methods. While critical of

any potential benefits of spanking for both extremes of the pediatric population (infants and

it is not done in anger, is not the primary method of discipline, and is administered with an open

hand.

1998 AAP Guidance for Effective Discipline

Two years later, in 1998, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a policy statement

on parental discipline, emphasizing three important components of effective discipline: a

positive, supportive, loving relationship between parent(s) and child; the use of positive

reinforcement strategies to increase desired behaviors; and removing reinforcement or applying

punishment to reduce or eliminate undesired behaviors. 8 These recommendations were based on

the expert opinions of members ofthe AAP' s Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and

Family Health. When specifically discussing corporal punishment, the Academy committee

noted the controversy surrounding such a discipline strategy, ultimately recommending that

"parents be encouraged and assisted in developing methods other than spanking in response to

undesired behavior."8

It is important to note that the AAP did not argue for a complete condenmation of

spanking, rather hedging their recommendations for pediatricians to "encourage" against

spanking. In large part due to the insufficient evidence for or against the practice of spanking,

this committee relied on individual studies citing associations between spanking and future

aggression, as well as studies showing the close link between spanking and more violent forms

of child abuse within families espousing corporal punishment. 8 There is only one reference within the policy statement about spanking infants, and, interestingly enough, it cites no

evidence. Spanking children less than 18 months of age, the AAP committee argues, increases

connection between the behavior and the punishment. 8 While one can hardly argue with such

claims, the fact that they chose not to research and to discuss parental discipline of infants serves

to leave pediatricians at a distinct disadvantage when discussing discipline issues with mothers

of young children.

Current Guidelines for Pediatrician Discussions with Parents on Discipline Methods

Despite the 1996 conclusions that children under the age of 2 should not be spanked, and

the 1998 policy statement encouragement against spanking, particularly of children under 18

months of age, the pediatrician's proscribed time to initiate discussion of any discipline matters

is at the nine-month visit?9 The four previous well-baby visits (1 month, 2 months, 4 months, and 6 months) include no discussion about parental discipline strategies. The AAP's advice

during the nine-month visit is to use consistent and positive discipline, limiting the use of"no",

using distraction, and being a role model28 As this study and others show, beginning a discussion of discipline at this point is too late, as significant numbers of parents have already

begun to develop personal disciplining strategies, often including spanking their children.

Discussions with parents about discipline could potentially be much more influential if they

begin within the first few months of the child's life and are readdressed throughout the child's

Appendix 4: Prevalence Data on Childhood Spanking

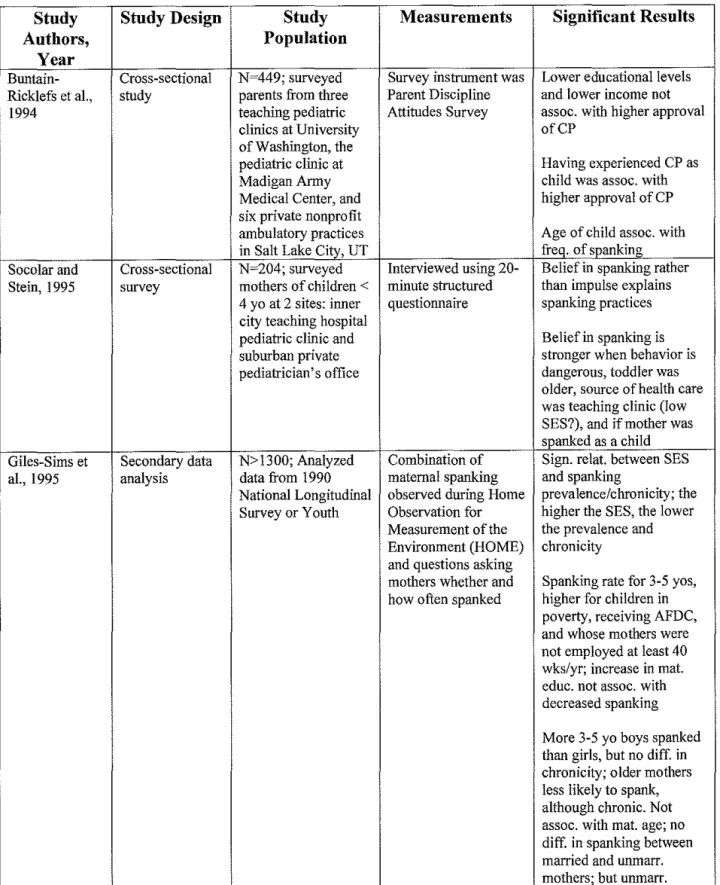

There are a number of studies published in the last fifteen years that assessed spanking

prevalence of children in the US population.1•7• 17• 20• 24-27• 47 Of these studies, several25"27 examine

spanking prevalence among children over the age of 2, outside of the range of this paper.

Oth ers ' ' · · ' 1 2 5-7 17 24 47 fi ocus on a WI 'd er range o ages, etermmmg span mg prev ence 10r f d . . k' a! "

children both above and below the age of2. Among these studies, spanking prevalence by the

age of2 ranges from 35% to 68%. For more specific discussion of these studies, see Table 3.

The remaining two studies3• 4 specifically assess spanking prevalence among US children

under the age of2, and are thus most closely comparable to this paper's surveyed population.

Slade and Wisso~, analyzing data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY),

sought to examine maternal self-reported spanking within the week prior to being surveyed.

These authors found that 38.7% of a nationally representative sample of mothers reported

spanking their child in the previous week, an average of3.422 times. In addition to getting

prevalence data, they looked at differences in spanking prevalence and frequency among mothers

of different races. African-American mothers reported the highest spanking prevalence and

frequency (49.3%; 3.993 times/wk), followed by white (35.6%; 3.247 times/wk) and Hispanic

(31.8%; 2.724 times/wk) mothers. In examining spanking prevalence among mothers of

different racial backgrounds, this paper will elucidate any similar findings, while also seeking to

separate the effects of socioeconomic status from the effects of race on spanking practices.

Socolar et al.4 surveyed a much smaller number of parents (n = 182) from North Carolina

and Alabama general pediatric clinics on discipline practices. Like the Slade study above, these

during the past week. When separated by state of residence, only 29% ofNC parents had

spanked their child in the past week, compared to 77% of AL parents. The large difference

between prevalence in these two southern US states is striking. Such a small study population

may overestimate prevalence among Alabama parents, though more research is needed to verify

this data. It should be interesting to compare North Carolina spanking prevalence from the

Appendix 5: Other Research on Maternal and Family Characteristics Predicting Spanking

In addition to assessing spanking prevalence among children in various subpopulations,

researchers have also focused much of their attention on determining whether specific maternal

aod family characteristics are associated with varying levels of spanking. The seven most

frequent characteristics assessed by these researchers are maternal age, ethnicity, education,

marital status, aod family income, as well as age aod gender of the child. An extended

discussion of this literature cao be found in Table 4.

The typical hypothesis regarding the effect of maternal age on spaoking prevalence is that

older mothers will spank less thao younger mothers. Young mothers, it is argued, are less

experienced thao older mothers, and are likely to be less finaocially secure and more stressed

thao their older counterparts. Five studies found a significaot association between maternal age

aod spaoking practices, all supporting the claim that increasing maternal age is inversely

associated with spanking prevalence.6· 7•11•20•21 In fact, Regalado eta!. found that adolescent

mothers were twice as likely as older mothers to spank their children.7 Two other studies have

come to more equivocal conclusions regarding this association. Giles-Sims eta!. have shown

that there is indeed ao inverse relationship between maternal age aod spanking prevalence,

however they note that there is no difference among older aod younger mothers in terms of

spanking frequency.26 Conversely, Straus eta!. found that there was no association between

maternal age aod spanking prevalence, but found an inverse relationship between maternal age

and spanking frequency.2

Regarding maternal ethnicity, much research has suggested that African-Americao

parents spank their children more thao other ethnic groups. The hypothesis for such a

more acceptable within the African-American cultural community, while others challenge that

etbnicity is often a surrogate for the effect of socioeconomic status on disciplinary practices.

Among the studies examined here, ten found an association between African-American ethnicity

and increased spanking beliefs and pattems.2· 6• 7• 11• 20· 22-26 The article by Hom et

a1?

4 shedssome interesting light on this debate. Given what the authors perceived was a confounding

relationship between ethnicity and socioeconomic status in previous studies when related to

disciplinary practices, they enrolled African-Americans of various socioeconomic backgrounds

in order to control for ethnicity. Their main ethnicity-specific finding was that middle and high

income African-Americans did appear to believe in spanking more than middle and high income

white Americans. Their conclusions on the relationship between disciplinary practices and

socioeconomic status will be further described below.

Spanking studies have been less conclusive on the relationship between maternal

educational achievement and disciplinary practices. Like ethnicity, the number of years of

schooling is often taken as a proxy for socioeconomic status. If this is an appropriate surrogate

marker, it is hypothesized that mothers with little education will spank their children more than

more highly educated mothers. The actual studies, however, challenge this hypothesis. While

six studies did indeed find a relationship between maternal education and spanking practices,

they are far from unanimous in the relationship described. Five studies11• 20-22• 25 support the

hypothesis, and suggest that less maternal education is associated with more severe spanking,

though one study11 found the relationship only significant when dealing with mothers of girls. In

contrast, Wissow found that mothers with a high school diploma were more likely to spank than

more highly educated African-American mothers were more severe in their spanking practices

than their lesser-educated peers.24 Not all studies found a relationship between maternal

d . d nki . h 4 26 27

e ucat10n an spa ng practices, owever. ' ·

It is often suggested that living with a spouse or partner eases the burden of child-rearing,

and thus it is hypothesized that mothers in such circumstances would be less likely to spank their

child than those living as a single mother. Two studies7• 11 supported this hypothesis, while a

third26 found that being single was associated with an increase in the frequency but not the

prevalence of spanking. Three other studies, however, found no such relationship between living

with a partner and disciplinary practices. 2• 4• 24

If high levels of stress are indeed hypothesized to increase maternal spanking prevalence

and/or frequency, then income is likely to provide an important surrogate for level of stress. In

light ofthe aforementioned debate on the associations between spanking practices and ethnicity,

many researchers have stressed that it is actually socioeconomic status that explains the disparate

disciplinary practices, not the specific ethnicity of the parent. The findings of this research, like

much of the findings mentioned earlier, are far from conclusive. Seven studies have found an

association between income and spanking practices.2• 6• 7• 11' 22• 23• 26 All of these studies found a

direct association between decreased income and increased spanking practices, with Smith and

Brooks-Gunn11 only finding the association among boys. Three studies, however, found no

association between income and spanking practices. 20• 24· 27 A final study by Socolar et a!. had

more equivocal results. 4 These authors found no association between spanking and specifically

income, yet they did find a positive association between spanking and the presence of long-term

suggests that, while the income association was not significant in this study, other socioeconomic

stressors, particularly over a long period of time, contribute substantially to spanking practices.

Other than maternal characteristics, there are studies suggesting that child characteristics

are also associated with spanking practices. One such characteristic is child age. As might be

expected, most prevalence studies (see discussion above) show an increase in spanking during

the infant years, a peak in the early childhood years, and a decline over the remaining course of

the child's development. Three studies support this data, noting an inverse relationship between

spanking frequency and child age. 7• 20' 27 Another related issue is the age at which parents find it

appropriate to spank their child. Two studies by Socolar and Stein47• 48 suggest that maternal

belief in spanking is associated with an increase in the child's age. Finally, Hom eta!. found no

association between spanking practices and child age.24

Another child characteristic frequently mentioned when discussing spanking practices is

child gender. There has been a tendency in both the lay and scientific press to assume that boys

are spanked more often than girls, though the actual scientific studies investigating this

. . h b . . a! F' d' 6 II 20 23 26 h . d d h h b

associatiOn ave een qmte eqmvoc . 1ve stu 1es ' ' · · ave m ee s own t at oys are

more likely to be spanked than girls, while another four studies 4• 7• 25• 49 have found no association

between spanking practices and gender of the child.

All of the seven maternal and child characteristics described in detail above will be

examined in this research paper. Given the complexity of the interactions between these

characteristics and parental disciplinary practices, our study can shed significant additional light

on distinguishing mothers who tend to spank from those who choose not to spank. Our

among infants, and therefore we expect to see the strongest association between maternal income

Appendix 6: Research on Long-term Outcomes of Children Who Have Been Spanked

While it is outside of the scope of this paper to delve into significant detail regarding

research on long-term consequences and outcomes in those children who have been spanked, a

brief summary of some of the relevant research into this topic is warranted. Not surprisingly,

much of the debate about long-term outcomes of spanking mirrors the debates on corporal

punishment in general, described in detail above. The anti-spanking group, led in large part by

Murray Straus at the University of New Hampshire, cites numerous studies and meta-analyses

which find an association between parental spanking and negative child outcomes such as

aggressiveness, anti-social behavior, psychological problems, and future delinquency.11.16 The

tenor of the discussions from this group tend to be quite passionate, with Straus in one extreme

example noting that any act of spanking perpetuates the "violent socialization" of our children.15

The most dispassionate and thorough research coming from this group was a meta-analysis by

Gershoff looking at the potential associations between corporal punishment and child behaviors

and experiences in 88 past studies.12 While acknowledging one potentially desirable finding,

that corporal punishment increases levels of immediate compliance in children, Gersh off found

that corporal punishment was associated with a number of more negative findings, including

increased aggression, decreased levels of moral internalization, increased delinquent, criminal,

and antisocial behavior, decreased mental health, and increased risk of being a victim of physical

abuse.12

The conditional spanking group, on the other hand, have stressed several problems with

the research methodology of the anti-spanking group, while also garnering a number of studies

which seem to suggest that appropriate forms of spanking can be effective and even beneficial

two meta-analyses on this topic, one looking at the association between nonabusive and

customary physical punishment and child outcomes, and another specifically comparing physical

punishment versus alternative disciplinary tactics in terms of subsequent child outcomes.36• 50

The first meta-analysis found that, after elimination of a number of articles included in the

Gershoff meta-analysis (due to faulty methodology), the results divided out almost equally into

those finding predominantly beneficial child outcomes (32%), predominantly detrimental

outcomes (34%), and neutral/mixed outcomes (34%).50 His second meta-analysis subsequently

found that "conditional" spanking was more effective than I 0 of 13 alternative disciplinary

tactics for reducing child noncompliance and antisocial behavior, and that only "overly severe"

or "predominant" use of punishment compared unfavorably to alternative methods.36 By

"conditional" spanking, Larzelere refers to "spanking under the limited conditions that have been

associated with better child outcomes (e.g., spanking when a 2-6-year-old refuses to comply with

time out)."36

The conflicting findings among the meta-analyses produced by both groups can be

explained in large part by the severe limitations of the research methodology in punishment

outcomes research. First, it is very difficult to prove that spanking at one point in a child's life

directly caused negative behaviors in subsequent life. Associations can be made, of course, but

causation is very difficult to establish. Secondly, the definitions of spanking, corporal

punishment, and physical punishment are all quite fluid across these studies. It is therefore not

surprising that studies with different definitions of critical exposures and outcomes come to

differing conclusions. Many of the studies arguing against all forms of spanking include a

spectrum of spanking practices, including quite severe, but not abusive, practices. The

only when appropriate disciplinary conditions are met. Finally, the conditional spankers have

argued that anti-spanking proponents need to control for initial child behavior before attempting

to link spanking with subsequent anti-social behavior. Without such a control, one might argue

for negative causation-that anti-social, oppositional children are more likely to be spanked as a

result of their initial behavior.

One interesting component ofthis spanking outcomes debate has centered around the

impact of spanking in different races or ethnicities on subsequent child behavior. Several

researchers have designed studies which suggest that spanking is not detrimental to the

subsequent behavior of African-American children, despite such an association among children

of European-American descent.3• 52-54 While these authors note that further longitudinal studies

are needed, their work raises interesting questions about cultural differences among American

parents, and further complicate an already challenging topic. Potentially challenging this issue

of ethnic differences in child outcomes following corporal punishment, Grogan-Kaylor found

that there was an association between corporal punishment and children's externalizing behavior

Appendix 7: ADDENDUM TO METHODS

Methods for systematic literature search

MEDLINE was searched to identify articles published between January 1975 and May

2008 using the search terms: "spank* AND corporal punishment", "spank* AND prevalence",

and "corporal punishment AND prevalence". Only English-language articles were considered.

In order to ensure that the search did not miss other articles that addressed spanking in young

children, the most recent 100 (out of206 total articles) abstracts within the query "spank*" were

also reviewed. Additional searches of Pediatrics journal website and the World Health

Organization website (both with query "spank*") was undertaken. The Cochrane Library and

the National Guideline Clearinghouse were consulted for references to spanking and corporal

punishment.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to all original articles identified by the

above searches. Given differences in discipline practices across the world, only articles

describing United States disciplining patterns were included. Special attention was given to

articles citing prevalence data on rates of spanking in US children, particularly those younger

than the age oftwo. Exclusion criteria were: case reports and editorials, articles on individuals

over the age of 13, articles on discipline practices without mention of spanking, articles on

spanking outside of the US, and articles specifically focused on child abuse.

After this exclusion of 187 abstracts from the Medline searches, 50 articles were

reviewed. These reviewed articles were given evidence grades on a scale from 0 - 18 according

to six categories (each worth 3 possible points): an accurate description of the study population;

among children younger than 2; discussion of maternal characteristics predicting spanking; the

TABLES AND FIGURES

T a e bl 1 D : escnpnon o fS urvey

·r

R espon eu s dt

(N = 2790)Characteristic Unweighted Weighted

Percent Percent

Age of child, months

3-8 30.8 30.7

9-13 24.5 24.9

14-18 21.9 21.5

19-24 22.8 22.9

Sex of child

Male 51.9 51.4

Female 48.1 48.6

Maternal Age

14-20 7.0 12.4

21-35 76.9 74.7

36-49 16.1 12.9

Marital status

Living with Spouse/Partner 89.7 80.5

Single/Widowed/Divorced 10.3 19.5

Education Status

Less than high school 10.9 17.4

HS grad/ some college 40.5 47.3

College graduate or higher 48.6 35.3

Ethnicity

African American I Black 11.4 16.5

Asian I Pacific Islander 2.2 1.6

Hispanic 10.6 13.6

White I Caucasian 73.6 65.4

Native American I Indian 0.9 1.3

Other 1.4 1.6

Annual household income

Less than $40,000 26.7 37.7

40,001 - 80,000 38.9 36.7

80,000+ 34.4 25.5

T a e bl 2 W. h d C : e1g1 te ompanson o fS span ers an k d N on- span ers S k (N

=

2790)Weighted Percent Number

Age of child, months

3-8 6.2 93.8 859

9-13 25.0 75.0 685

14-18 44.5 55.5 611

19-24 57.3 42.7 635

Sex of child

Male 32.3 67.7 1449

Female 29.3 70.7 1341

Maternal Age

14-20 38.6 61.4 196

21-35 30.6 69.4 2146

36-49 24.7 75.3 448

Marital status

Living with Spouse/Partner 30.7 69.3 2504

Single/Widowed/Divorced 31.5 68.5 286

Education Status

Less than high school 27.4 72.6 304

HS grad/ some college 33.6 66.4 1131

College graduate or higher 28.8 71.2 1355

Ethnicity

African American I Black 30.4 69.6 318

Asian I Pacific Islander 44.9 55.1 61

Hispanic 23.7 76.3 295

White I Caucasian 32.5 67.5 2052

Native American I Indian 5.1 94.9 26

Other 35.3 64.7 38

Annual household income

Less than $40,000 29.2 70.8 745

40,000- 80,000 34.7 65.3 1085

80,000+ 27.7 72.3 960

Table 3: Logistic Regression Models of Spanking Behavior on Maternal Characteristics (N = 2790)

Independent Models

Variables Bivariate Full Multivariate Final

Multivariate

Odds P value Odds P value Odds Pvalue

Ratio Ratio Ratio

Age of child, months* 1.19 < 0.001 1.20 < 0.001 1.20 < 0.001

Sex of child 1.15 0.152 1.11 0.375 --

--Maternal Age*

21-35 1.35 0.030 1.47 0.012 1.50 0.008

36-49 1.00

--

1.00--

1.00--Marital Status 0.96 0.787 1.04 0.831

--

--(single/widowed/ divorced as reference) Educational Status

LessthanHS 0.94 0.683 1.08 0.759

--

--HS grad/ Some col! 1.26 0.025 1.40 0.010

--

--College grad 1.00

--

1.00--

--

--Ethnicity*

Black 0.90 0.506 0.77 0.201 0.79 0.222

Asian 1.67 0.100 2.14 0.048 2.16 0.044

Hispanic 0.65 0.011 0.51 0.010 0.48 0.001

White 1.00

--

1.00--

1.00--Native American 0.11 0.003 0.06 0.001 0.06 0.001

Other 1.13 0.774 0.90 0.839 0.85 0.761

Income Level*

< $40,000 1.07 0.573 1.16 0.396 1.31 0.082

$40-80,000 1.38 0.004 1.38 O.oJ8 1.52 0.001

$80,000+ 1.00

--

1.00--

1.00--*

p < 0.05Figure 1: Spanking Frequency Among Spankers (N = 813)

Once Twice 3-STimes 6-10Times 11-20Times 20+Times

Figure 2: Spanking curve for all children by age (in months) with 95% Cis

0 00

0

"'

Spanking Curve (all Respondents) with 95% Cis

-.,._

""'

'"'" '

"'...;'--'

-

...--' ....

'

',

'

...'

' ,

...

'

... ... '-...._:...

:---··· ··· ··· ···

···""'·~;=·=···... ".:.::.:::.:.::.::

=····

-

.......

,

....

__

--7"8 9"10 11-12 13-14 15c16 17'18 19-20 21-22 23-24

Age of Child (in 2 month increments)

D

Spanking Curve

by

Maternal Age

'C:f''

~.·~-~T'--r---,~--~~.-~-c--~~~,_---,---,-0

~

3'-4 5.-6 7-8 9•10 1.1.-12.13."14 15-16 .17A8 19C20 21-22 23.-24

Age of Child (in 2 month interVals)

14-20 21-351

----3649 .

Sp<:mking Curve by Maternal Ethnicity

3'-4 5-6 7-8 9-.10 11-12 1.3-14 15-16 17-18 19-20 21-22 23-24

Age of Child (in 2 month intervals)

---White - - - Hispanic

0.

0

..,-Spanking C.urve by Family Income

34 5c5 yea 9"10 11-12 13-14 15-19 17-18 19-20 21-22 23-24

Age.ofChild (in 2 month intervals)

. - - - < $40,000

- - - > $80,000

Table 3. Selected studies of spanking prevalence

Study Study Design Study Population Measurements Significant

Authors, Results

Year

Buntain-Ricklefs Cross-sectional N-449; surveyed Survey instrument was Not broken down by

eta!., 1994 study parents from three Parent Discipline age

teaching pediatric Attitudes Survey

clinics at University -54.3% of parents

of Washington, the admitted to hitting

pediatric clinic at child with object

Madigan Army (board, stick, wire, etc.)

Medical Center, and -57% admitted to

six private nonprofit hitting with belt

ambulatory practices -92.9% admitted to

in Salt Lake City, UT sJl3nking

Socolar and Cross-sectional N-204; surveyed Interviewed using 20- -19% believed there are

Stein, 1995 survey mothers of children < minute structured times when it is

4 yo at 2 sites: inner questionnaire appropriate to spank a

city teaching hospital child< I yo

pediatric clinic and -74% believed above

suburban private when child was

pediatrician's office between I and 3

-42% had spanked their own child within past week

Giles-Sims et al., Secondary data N> 1300; Analyzed Combination of 3-5 yos- 60.7% of

1995 analysis data from 1990 maternal spanking mothers had spanked

National Longitudinal observed during Home child in past week, a Survey or Youth Observation for mean of 3 times

Measurementofthe

Environment (HOME) Of those spanking, and questions asking 33.1% said once a mothers whether and week, 24.0% twice, how often spanked 17.4%3x/wk;

14.3%4-5x/wk; 6.5% 6-9x/wk; 3.1% 10-14x/wk; 1.5% 15+x

Day et al., 1998 Secondary data N-13,017; Analyzed # oftimes the I yo- 50% of mothers analysis data from 1987-88 respondent spanked spanked sons at least

National Survey of child during week prior once (44% 1-5 times;

Families and to survey 6% 6+x)

Households (a 51% of mothers

national probability spanked their daughters

sample) at least once (43% 1-5

times; 8% 6+x) 25% offathers spanked sons (22% 1-5 times; 3% 6+x);

spanked sons at least once (50% 1-5 times; 14% 6+x)

67% of mothers spanked their daughters at least once (62% 1-5

times; 5% 6+x)

56% offathers spanked sons (48% 1-5 times; 8% 6+x);

46% of fathers spanked daughters (41% 1-5 times; 5% 6+x)

3 yo- 70% of mothers spanked sons at least once ( 63% 1-5 times; 7% 6+x)

53% of mothers spanked their daughters at least once (47% 1-5 times; 6% 6+x) 55% of fathers spanked sons (52% 1-5 times; 3% 6+x);

34% of fathers spanked daughters (34% 1-5 times; 0% 6+x)

Straus and Secondary data N-991; Analyzed data Measured prevalence Overall prevalence rate Stewart, 1999 analysis from 1995 Gallup of 6 forms of CP (slap for any of 6 CP

survey (random digit on hand or leg, spank categories was 35% for stratified probability on buttocks, pinching, infants ( < 2 yo) and

design shaking, hitting on reached peak of 94%

buttocks with belt or by ages 4-5 paddle, and slap on

face) using the Parent- Over l/3 of infants Child Conflict Tactics were hit by parents; CP

Scale was most chronic by

parents of2 yos, with avg. of l8x/year

Between 0-2, 31.8% of parents spanked on bottom with hand; 36.4% slapped on hand, arm, or leg; 2.5% hit on bottom with object other than hand; 0.5% slapped on face, head, or ears; 2.8% pinched, and 4.3% shook their child