ANTI-TUMOUR TREATMENT

The efficacy of arsenic trioxide for the treatment of relapsed

and refractory multiple myeloma: A systematic review

Christoph Röllig

*, Thomas Illmer

1Medizinische Klinik und Poliklinik I, University Hospital Dresden, Fetscherstr. 74, 01307 Dresden, Germany

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 10 February 2009

Received in revised form 13 April 2009 Accepted 15 April 2009 Keywords: Multiple myeloma Plasmacytoma Relapsed Refractory Arsenic ATO Efficacy Systematic review

s u m m a r y

Arsenic trioxide (ATO) has been proposed as an option for the treatment of relapsing or refractory multi-ple myeloma. In order to critically appraise the published clinical evidence, a systematic search of the databases PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library was performed. Studies were selected according to prospectively defined criteria. Eventually 16 articles met the inclusion criteria. Six trials evaluated ATO as a single agent or in combination with ascorbic acid and ten trials added ATO to other cytostatic agents. Apart from one randomized controlled trial (RCT), all other studies were designed as case series. The patient numbers were generally small, treatment regimens differed both regarding the dosage of ATO and combinations with other drugs. Monotherapy with ATO resulted in par-tial response rates between 0% and 17% and minimal responses of 7–33%, resulting in mean overall response rates of 30%. Overall response rates in combined regimens varied widely between 12% and 100%. Response rates for patients in the three arms of the RCT did not differ significantly. The results demonstrate the potential efficacy of ATO in refractory multiple myeloma, but the validity of these find-ings is reduced by considerable methodological flaws. RCTs should further investigate the efficacy of ATO or new arsenicals in order to overcome methodological concerns of the studies presented here. With respect to the higher evidence level of new substances such as bortezomib or lenalidomide, at present ATO has no role in routine management of relapsed or refractory myeloma.

Ó2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Background

Multiple myeloma is a B-cell malignancy characterised by an accumulation of monoclonal plasma cells and the production of monoclonal immunoglobulin. Despite improvements in the re-sponse rates due to the inclusion of novel drugs as well as high-dose chemotherapy (HDCT) with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), patients continue to eventually relapse and become resis-tant to available substances. Therefore, new treatment modalities are being evaluated to improve survival in patients refractory to chemotherapy.1

Arsenicals have been used as therapeutic agents for thousands of years. Despite their benefits, concerns about toxicity and carcin-ogenicity generated reluctance among physicians to use arsenic compounds therapeutically. In the 1970s reports from China indi-cated remarkable rates of remission and long-term survival in patients with acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL) who were treated with a formulation of arsenic trioxide (ATO). This evidence, together with the demonstration of anticancer activity of ATO in

relevant in vitro and in vivo models suggested that its risk-benefit profile should be reconsidered and its potential as a therapeutic agent in other haematological malignancies should be explored. Myeloma was an obvious candidate, given the lack of curative treatment, its complex pathogenesis and the large number of path-ways that can be efficiently targeted by the molecular mechanisms of ATO.1–3Thereby it has been shown that ATO affects both the extrinsic receptor-mediated pathway and the intrinsic mitochon-dria associated pathway of apoptosis in myeloma cell lines. This mechanism of action would be an attractive tool to overcome the well known resistance of myeloma cells to a multitude of agents. After promising preclinical trials, ATO has been used in clinical tri-als since 1998 in patients with multiple myeloma.4

This review aims to critically appraise the published clinical research about the effect of ATO on multiple myeloma in adults requiring systemic treatment for relapsed or refractory disease. Criteria for selecting studies for the review

Types of study design

All clinical study designs apart from case reports were eligible for inclusion, i.e. randomised controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, case-control studies and case series. Systematic but not 0305-7372/$ - see front matterÓ2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.04.007

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +49 351 458 13775; fax: +49 351 458 5362.

E-mail addresses:christoph.roellig@uniklinikum-dresden.de(C. Röllig),thomas. illmer@uniklinikum-dresden.de(T. Illmer).

1 Tel.: +49 351 458 4190; fax: +49 351 458 5362.

Contents lists available atScienceDirect

Cancer Treatment Reviews

unsystematic narrative reviews were also eligible. There were no restrictions on the country of research, but the language of publi-cation was restricted to English.

Types of participants

Adult patients suffering from multiple myeloma in progressive stadium II or III according to the Salmon and Durie classification5 who had either relapsed from standard first-line therapy or were shown to have chemotherapy-refractory disease. All publications involving in vitro studies, investigations on cell lines and human xenografts were excluded.

Types of interventions

ATO containing therapy regimens.

Types of outcome measures

Overall response rates (complete remission plus partial remis-sion plus minimal response), and odds ratios or risk ratios where applicable, furthermore probabilities for overall survival (OS) and progression free survival (PFS).

Search strategy for identification of studies

The databases Pubmed (since 1950), Embase (since 1980), Web of Science (since 1970) and the Cochrane Library were searched in November 2008 for a combination of text and medical subject heading (MeSH) terms. The terms covered the two major search concepts multiple myelomaand arsenic (see Appendix 1 for full search strategies). Studies identified through this approach were screened by titles in a first step. The abstracts of the remaining publications were screened in a second step. After exclusion of non-relevant publications and identifications of duplicates from the different databases, the remaining papers were evaluated in the full text version for in- and exclusion criteria and for relevant articles in the reference lists.

Methods of the review

Data for study characteristics and clinical response were extracted and brought into table format. The quality of the pub-lished studies was assessed using a validated checklist for the methodological quality for health care interventions.6Additionally, the level of evidence for each study was determined according to the evidence levels developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN).7Heterogeneity of studies was assessed in order to decide whether the results of the different studies could be synthesised in a meta-analysis.

Search results

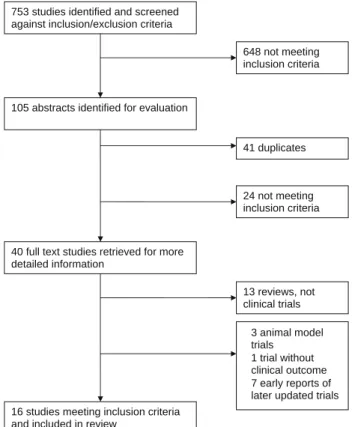

The database search produced 194 citations from Pubmed, 301 from Embase, 247 from the Web of Science and 4 from the Cochra-ne Library. Hand searching in the abstract collection of the most re-cent annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology (2007) and review literature3 resulted in seven additional publications. After initial screening of all 753 titles, 105 abstracts were evaluated and 29 full-text studies retrieved for more detailed evaluation. The search of the article references did not produce additional publica-tions. There were seven publications reporting early results of later published trials.4,8–13These publications were also excluded. Even-tually, 16 articles met the inclusion criteria. The literature search and study selection is depicted inFig. 1.

Characteristics of studies

Fifteen of 16 included intervention studies were designed as case series and one study included ATO in an RCT setting.14 Hof-meister et al., published results of an ATO containing regimen as first-line therapy in newly diagnosed myeloma patients.15 Baz et al. treated both relapsed, refractory and high-risk previously un-treated patients.16In order to comprehensively list all available lit-erature on clinical trials using ATO in myeloma patients, these publications were included in the review. All other trials recruited participants who had progressive multiple myeloma, either in a re-lapsed state or classified as being refractory to available treatment. The median age varied between 54 and 66, two studies did not re-port age.17,18The patient numbers were generally small, ranging from 4 to 65. The majority of studies (10 of 16) evaluated less than 20 patients.15–24Studies were published between 2002 and 2008 and conducted in developed countries, most of them in the USA, furthermore in France, the Netherlands, Belgium and Turkey, Italy, Austria and Israel and Dey et al. reported results from India.22Six studies were published in abstract format only.14,16–18,20,22 Treat-ment regimens differed considerably both regarding the dosage of ATO and regarding combinations with other drugs available for the treatment of multiple myeloma. ATO dosage ranged from 0.12525 to 0.3 mg/kg per day.18 Six studies used ATO as mono-therapy or in combination with ascorbic acid.18,19,22–24,26 Other cytostatic drugs used in combination regimens were bortezomib,25 melphalan,14,17,21,27dexamethasone,15,16,20,28,29thalidomide16and doxorubicine.15All 16 studies used the change in the amount of serum monoclonal protein as main outcome measure for the deter-mination of the response rate (complete response CR, partial response PR, minimal response MR, stable disease SD, progressive disease PD). Five studies additionally investigated the probability of overall survival (OS) and progression free survival (PFS).14,19,25,27,28 The detailed characteristics of the studies are summarised inTable 1.

753 studies identified and screened against inclusion/exclusion criteria

105 abstracts identified for evaluation

40 full text studies retrieved for more detailed information

16 studies meeting inclusion criteria and included in review

648 not meeting inclusion criteria 41 duplicates • 3 animal model trials • 1 trial without clinical outcome • 7 early reports of

later updated trials 13 reviews, not clinical trials 24 not meeting inclusion criteria

Methodological quality of included studies

The publication of Gesundheit et al. reported the use of ATO in four myeloma patients with relapse after bone marrow transplan-tation. Apart from the statement that all patients showed evidence of response, no further details were given.18This report was included in this review in order to comprehensively list all published evidence about the use of ATO in myeloma patients but will be excluded from the following quality assessment and results.

The qualitative assessment of the remaining 15 publications showed that studies had clearly formulated aims and descriptions

of the interventions, the number of responding patients and the overall number were reported clearly enabling the reader to check results and conclusions. Response criteria were not stated in five studies. Inclusion criteria for treatment were generally relapse or chemo-resistance, but it remained unclear in all studies how patients were selected and how the patient sample in the study related to the overall group of relapsed or refractory myeloma patients. Most of the studies were case series, selection criteria were not uniform. The only trial with a control group was the RCT conducted by Qazilbash et al.14

Information about the randomisation procedure and blinding was not available. Patient characteristics in each group were not Table 1

Study characteristics: first author, publication year, reference, country of trial (NL = Netherlands, B = Belgium, I = Italy, A = Austria), study design, number of patients, median age (– = not reported), treatment regimen (ATO = arsenic trioxide, AA = ascorbic acid = vitamin C, Dex = dexamethasone, Mel = melphalan, Thali = thalidomide, Doxo = liposomal doxorubicine, Vin = vincristine), HD = high dose, outcome measures (CR = complete remission, PR = partial remission, MR = minimal response), level of evidence (LOE) according to classification of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN).

First author (year) Country Study design Number of patients Median age

Treatment regimen Outcome measure LOE

(SIGN) Abou-Jawde et al.

(2006)

USA Case

series

20 64.5 ATO 0.25 mg/kg + AA 1 g + Dex 40 mg Response rate (CR + PR + MR), PFS, OS 3 Bahlis et al. (2002) USA Case

series

6 55.5 ATO 0.15/0.25 mg/kg + AA 1 g Response rate (CR + PR + MR) 3

Baz et al. (2006) USA Case

series

16 57 ATO 0.25 mg/kg + AA 1 g + Dex 20 mg + Thali 100 mg

Response rate (CR + PR + MR), PFS 3 Berenson et al. (2007) USA Case

series 22 63 ATO 0.125/0.25 mg/kg + Bortezomib 0.7/1.0/1.3 mg/m2 + AA 1 g Response rate (CR + PR + MR), TTP, PFS, OS 3 Berenson et al. (2006) USA Case

series

65 66 ATO 0.25 mg/kg + AA 1 g + Mel 0.1 mg/kg Response rate (CR + PR + MR), PFS, OS 3 Berenson et al. (2004) USA Case

series

14 – ATO 0.25 mg/kg + AA 1 g + Mel 0.1 mg/kg Response rate (CR + PR + MR) 3

Birch et al. (2003) USA Case

series

16 65 ATO 0.25 mg + AA 1 g + Dex 40 mg Response rate (CR + PR + MR) 3

Borad et al. (2005) USA Case

series

10 60.5 ATO 0.25 mg/kg + AA 1 g + Mel 0.1 mg/kg Response rate (CR + PR + MR) 3

Dey et al. (2007) India Case

series

15 65 ATO 10 mg absolute (0.14 mg/kg) Response rate (CR + PR) 3

Gesundheit et al. (2005)

Israel Case

series

4 – ATO 0.15/0.3 mg/kg + AA 1 g Undefined ‘‘evidence of response” 3

Hofmeister et al. (2008)

USA Case

series

11 62 ATO 0.25 mg/kg + liposomal

Doxo 40 mg/m2 + Vin 1.4 mg/m2 + Dex 40 mg

Response rate (CR + PR) 3

Hussein et al. (2004) USA Case series

24 63 ATO 0.25 mg/kg Response rate (CR + PR + MR) 3

Munshi et al. (2002) USA Case series

14 56 ATO 0.15 mg/kg Response rate (CR + PR + MR) 3

Qazilbash et al. (2007)

USA RCT 48 54 Mel 200 mg/m2

+ AA 1 g +arm 1: no ATO,

arm 2: ATO 0.15 mg/kg,arm 3: ATO 0.25 mg/kg

Response rate (CR + PR), PFS, OS 1 Rousselot et al.

(2004)

France Case

series

10 55.5 ATO 0.15 mg/kg Response rate (CR + PR + MR) 3

Wu et al. (2006) NL/B/Turkey/ I/A

Case series

20 65 ATO 0.25 mg/kg + AA 1 g + Dex 40/20 mg Response rate (CR + PR + MR) 3

Table 2

Results of case series using ATO as monotherapy with or without ascorbic acid: first author, publication year, reference, treatment regimen (ATO = arsenic trioxide, AA = ascorbic acid = vitamin C), patient numbers total, CR = complete remission, PR = partial remission, MR = minimal response, SD = stable disease, PD = progressive disease, OR = overall response = CR + PR + MR, OR in % of total number of patients, duration of response (– = not reported, pt = patient), comments.

First author (year) Treatment regimen Patient number OR (%) Duration of response Comments Total CR (%) PR (%) MR (%) SD (%) PD (%) Munshi et al. (2002) ATO mono 14 0 (0) 2 (14) 1 (7) 8 (57) 3 (21) 3 (21)

1–6 weeks Varying treatment durations Rousselot et al. (2004) ATO mono 10 0 (0) 0 (0) 3 (30) 2 (20) 5 (50) 3 (30)

1–3 weeks Varying treatment durations, varying dosages, treatment responses very short

Hussein et al. (2004) ATO mono 24 0 (0) 0 (0) 8 (33) 6 (25) 5 (21) 8 (33) 25–515 days (1– 17 months)

Varying treatment duration, two patients

did not even complete one cycle, five patients not ‘‘evaluable” Dey et al. (2007) ATO mono 15 5 (33) 6 (40) 0 (0) 2 (13) 3 (20) 11 (73)

– Follow-up time and duration of response not reported Bahlis et al. (2002) ATO + AA 6 0 (0) 1 (17) 1 (17) 3 (50) 0 (0) 2 (34) 1 pt 2 months, 1 pt 4 months

Varying treatment duration, varying dosages, one patient not evaluable because of non-secretory disease

Gesundheit et al. (2005)

ATO + AA 4 – – – – – – – No response criteria, outcome reported as ‘‘patients showed

reported separately except for a difference in the beta2-microglob-ulin levels. However, it was stated that patients were evenly matched.

According to the SIGN framework, all studies except the RCT by Qazilbash et al. are categorised as level 3, the latter trial has an evidence level of 1 (i.e. RCTs with high risk of bias) due to the relatively small patient number and poor reporting in abstract format.

Results

Variations within and between studies, particularly inhomoge-neous dosages and treatment durations did not allow a quantita-tive data synthesis. Therefore, a narraquantita-tive synthesis approach was chosen.

ATO as single agent or in combination with ascorbic acid

Six studies used ATO as monotherapy or in combination with ascorbic acid.18,19,22–24,26The report by Gesundheit et al. was not de-tailed enough for response evaluation18 and was excluded from analysis. In the remaining five trials, patient numbers were small, ranging from 619to 24.26No complete remissions were reported by four trials and partial remission rates ranged from 0%4,26to 17%.19The abstract by Dey et al. reported unusually high response rates with a CR rate of 33% (five of 15 patients) and a PR rate of 40%.22There were no minimal responses (MRs) in the report by Dey et al., MR rates in the remaining publications varied between 7%1and 33%.26This resulted in overall response rates from 21%1to 73%.22 The achieved remissions lasted from one week23,24to 17

months.26 Dey et al. did not report time intervals for effect duration.22

ATO as part of a combined cytostatic regimen

Overall response rates in the 10 trials using ATO in addition to dexamethasone, melphalan or other cytostatic agents varied widely between 12%20 and 100%.21 Complete remissions were achieved in the minority of cases (range, 0–25%). Most of the OR rates comprised PR and MR. The duration of responses varied greatly between studies, ranging from 029to 24 months.14 Four studies did not report time intervals for effect duration.15–17,25 No response pattern with respect to different ATO combinations or dosages could be detected and no distinct differences in re-sponse rates were observed between trials using ATO as mono-therapy (21–73%), ATO in combination with ascorbic acid (33%) or ATO in combination with other cytostatic agents (13–100%).

ATO in the randomised controlled trial

The study design of Qazilbash et al.14added ATO to the routinely used conditioning melphalan high-dose chemotherapy before autologous stem cell transplantation in an RCT design. Patients in arm 1 did not receive additional ATO while arms 2 and 3 included ATO in different dosages added to the standard melphalan regimen. The response rates were 85% in all three arms.14The authors report that both response rates and survival did not differ significantly be-tween treatment arms (pvalue for CR, ORR, PFS or OS among the three arms were 0.9, 0.9, 0.5 and 0.6, respectively).

Table 3

Results of case series using ATO in combination with cytostatic agents: first author, publication year, reference, treatment regimen (ATO = arsenic trioxide, AA = ascorbic acid = vitamin C, Dex = dexamethasone, Mel = melphalan, Thali = thalidomide, Doxo = liposomal doxorubicine, Vin = vincristine), HD = high dose, patient numbers total, CR = complete remission, PR = partial remission, MR = minimal response, SD = stable disease, PD = progressive disease, OR = overall response = CR + PR + MR, OR in% of total number of patients, duration of response (– = not reported, pt = patient), comments.

First author (year)

Treatment regimen Patient number OR

(%) Duration of response Comments Total CR (%) PR (%) MR (%) SD (%) PD (%) Birch et al. (2003) ATO + AA + Dex 16 0 (0) 1 (6) 1 (6) 5 (31) 5 (31) 2 (12)

‘‘SD for 5–15 months” No response criteria, four patients inevaluable, varying durations of treatment, some pts did not complete even one treatment cycle, SD duration from 5 to 15 months Wu et al. (2006) ATO + AA + Dex 20 0 (0) 2 (10) 6 (30) 5 (25) 7 (35) 8 (40)

0–10 months Varying treatment duration, not all responses stated, no response criteria Abou-Jawde et al. (2006) ATO + AA + Dex 20 2 (10) 4 (20) 5* (25) 5* (25) 4 (20) 11 (55) Median 357 d (12 months) (21–701 d) Median PFS 316 d (10.5 m), median OS 962 d (32 m); *decrease of monoclonal protein of 25% to 50% (MR) referred to as SD instead as MR; number of SD in the original publication therefore 10, no MR category Berenson et al. (2004) ATO + AA + Mel 14 0 (0) 4 (29) 4 (29) 3 (21) 3 (21) 8 (58)

– Varying treatment duration, no time of follow-up (SD?), response criteria not stated

Borad et al. (2005) ATO + AA + Mel 10 0 (0) 4 (40) 6 (60) 0 (0) 0 (0) 10 (100) Six pts ‘‘sustained response”

Varying durations of treatment, varying dosages, first six patients received additional dexamethasone, no response duration, no response criteria

Berenson et al. (2006) ATO + AA + Mel 65 2 (3) 15 (23) 14 (22) 25 (39) 9 (14) 31 (48)

1–16 months Varying treatment durations, nine patients did not even complete one cycle

Berenson et al. (2007) ATO + AA + Bortezomib 22 0 (0) 2 (9) 4 (18) 9 (41) 7 (32) 6 (27)

– Median follow-up 13 months (7–20), median PFS 5 months, median OS not reached yet, PFS at 12 months 34%, OS at 12 months 74%, duration of response not reported

Baz et al. (2006)

ATO + AA + Dex + Thali 13 0 (0) 4 (31) 0 (0) 8 (62) 1 (8) 4 (31)

– Median follow up 9.5 months, median PFS 9.4 months; duration of response not reported

Hofmeister et al. (2007)

ATO + Doxo + Vin + Dex 11 0 (0) 4* (36) 0 (0) 6 (55) 1* (10) 4* (36)

– Follow-up time and duration of response not reported; *according to response table in publication only 3 PRs (27%)

Qazilbash et al. (2007)

HD-Mel + AA +arm 1: no ATO,arm 2: ATO 0.15arm 3: ATO 0.25 48 12 (25) 29 (60) ? ? ? 41 (85) PFS after 24 months 59%, OS after 24 months 91%; median PFS 24 months

Combination with conditioning regimen for autologous SCT, 2 treatment arms with ATO, one without ATO; response rates and survival not significantly different between treatment arms

All results for ATO monotherapy and ATO in combined cyto-static regimens are summarised inTables2 and 3, respectively. Discussion

This review assessed the published literature about the treatment of patients suffering from relapsed or refractory multi-ple myeloma with an ATO containing regimen. The findings dem-onstrate the potential of ATO to lower the circulating monoclonal protein. Promising response rates up to 100% from case series are documented. However, the response rates show a considerable variability and methodological flaws have to be considered.

In order to evaluate the efficacy of ATO on relapsed or refrac-tory multiple myeloma, it is necessary to focus on the trials using ATO as a single agent. Four of five evaluable studies show consis-tent OR rates around 30% exclusively consisting of PR or MR. However, Dey et al. report in their small case series 33% CRs, 40% PRs and no MRs. This remarkable difference and variations between all five trials can be explained by a number of factors reducing the validity of the results. The study design of case series is associated with a high potential for bias to internal validity due to possible selection bias. The category of relapsed myeloma pa-tients represents an inhomogeneous group of papa-tients with a great variation of pre-treatment regimens possibly influencing the susceptibility to ATO. Furthermore, differences in the distribu-tion of response determinants such as serum beta2-microglobulin, cytogenetics30 and other unknown factors may have confounded the results of the studies. Since no control group was used, an adjustment for confounding was not possible. Another somewhat important factor accounting for the varying response rates might be differences in the response definition, which is not stated in a number of reports.

The results of the combined treatment regimens containing ATO show even greater variability and it is difficult to determine how much of the effect was produced by ATO itself as opposed to the other cytostatic agents. Apart from the trial of Qazilbash et al., the CR rates are low (0–10%) and OR rates comprised mostly PRs and MRs (OR rates ranging from 12% to 100%). Methodological flaws mentioned earlier such as selection and measurement bias, small sample size and confounding apply to these trials, too, and account for the wide variation of the results.

The RCT by Qazilbash et al. is the only trial with an ATO-nega-tive control arm. Since clinical outcomes did not differ between the intervention arms it can be concluded that the observed effect is mainly attributable to melphalan. The results show – with a fair amount of evidence – that in the setting of high-dose melphalan, the addition of ATO does not influence the clinical outcome of mye-loma patients.

Most likely, the patient samples of all trials were highly selected and included patients may have been in a better physical condition than the average myeloma patients in this stage of disease. Treat-ment was administered and closely monitored in specialised hae-matological centres, affecting the generalisability of the results.

In summary, due to the methodological drawbacks, the evi-dence level for the clinical efficacy of ATO in multiple myeloma is low. However, some case series report high response rates and preclinical data suggest a promising modulatory effect of ATO in combination with pro-apoptotic drugs. This is especially true for novel combination of ATO with drugs interfering with critical sig-nalling pathways like the MAPKinase cascade.31,32

Potential side effects such as sensory neuropathy or QTc prolon-gation should be kept in mind. Randomized controlled trials should further investigate the efficacy of ATO or possibly new related sub-stances in order to overcome methodological concerns of the stud-ies presented here. The efficacy of new substances for the treatment of relapsed and refractory myeloma such as

thalido-mide,33 bortezomib34,35 or lenalidomide36–38 was demonstrated in controlled trials with larger numbers of patients, resulting in a higher evidence level. Since current clinical results for ATO are too preliminary, ATO should only be used as an experimental or salvage option in the context of controlled clinical trials.

Reviewers’ conclusions

This systematic review about the treatment of relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma patients with an ATO containing reg-imen suggests evidence for the efficacy of ATO, partly with high re-sponse rates. However, this assessment is based on the availability of case series and one relatively small RCT and there are concerns about the validity and generalisability of the results. Therefore, at present there is no role for ATO in the routine clinical management of multiple myeloma. ATO should not be used outside of RCTs and outcome measures should not only include the reduction of serum monoclonal protein, but also patient relevant data such as progres-sion-free survival and overall survival.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Acknowledgements

Christoph Röllig would like to thank John Browne and Andrew Hutchings, of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, for their excellent training in systematic reviews.

Appendix 1. Search strategies and results

# Search history COCHRANE LIBRARY Results

1 MeSH descriptorMultiple Myelomaexplode all trees

582 2 MeSH descriptorPlasmacytomaexplode all trees 7

3 (Myeloma):ti,ab,kw 1375

4 (Plasmacytoma):ti,ab,kw 8

5 (plasmocytoma):ti,ab,kw 4

6 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5) 1381

7 MeSH descriptorArsenicalsexplode all trees 35

8 (Arsen*):ti,ab,kw 135

9 (#7 OR #8) 144

10 (#6 AND #9) 4

# Search history WEB OF SCIENCE Results

1 TS = (myeloma) 32559

DocType = All document types; Language = All languages; Databases = SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI; Timespan = 1970–2008

2 TS = (plasmocytoma) 540

DocType = All document types; Language = All languages; Databases = SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI; Timespan = 1970–2008

3 TS = (plasmacytoma) 2967

DocType = All document types; Language = All languages; Databases = SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI; Timespan = 1970–2008

# Search history WEB OF SCIENCE Results

4 #3 OR #2 OR #1 34954

DocType = All document types; Language = All languages; Databases = SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI; Timespan = 1970–2008

5 TS = (arsen*) 49974

DocType = All document types; Language = All languages; Databases = SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI; Timespan = 1970–2008

6 #5 AND #4 247

DocType = All document types; Language = All languages; Databases = SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI; Timespan = 1970–2008

# Search history EMBASE Results

1 Myeloma 30530 2 Plasmacytoma 4821 3 Plasmocytoma 665 4 1 OR 2 OR 3 33726 5 Arsen* 21410 6 4 AND 5 301

# Search history PUBMED Results

1 ‘‘Multiple Myeloma” [MesH] 24778

2 ‘‘Plasmacytoma” [MesH] 6900 3 Myeloma 36562 4 Plasmacytoma 8101 5 Plasmocytoma 8736 6 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 42239 7 Arsen* 23697 8 ‘‘Arsenicals” [MesH] 8504 9 7 OR 8 24657 10 6 and 9 194 References

1. Munshi NC. Arsenic trioxide: an emerging therapy for multiple myeloma.

Oncologist2001;6(Suppl. 2):17–21.

2. Anderson KC, Boise LH, Louie R, Waxman S. Arsenic trioxide in multiple myeloma: rationale and future directions.Cancer J2002;8:12–25.

3. Dilda PJ, Hogg PJ. Arsenical-based cancer drugs.Cancer Treat Rev 2007;33: 542–64.

4. Rousselot P, Arnulf B, Poupon J, et al. Phase I/II study of arsenic trioxide in the treatment of refractory multiple myeloma.Blood2003;102:380B–1B. 5. Salmon SE, Durie BG, Hamburger AW. A new basis for treatment of multiple

myeloma.Schweiz Med Wochenschr1978;108:1568–72.

6. Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions.J Epidemiol Community Health1998;52: 377–84.

7. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 50. A guideline developer’s handbook. Edinburgh; 2008.

8. Berenson JR, Matous J, Ferretti D, et al. A phase I/II trial evaluating the combination of arsenic trioxide, bortezomib and ascorbic acid for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma.Blood2005;106:721A.

9. Berenson JR, Boccia R, Siegel D, et al. A multicenter phase II study of combination treatment with melphalan, arsenic trioxide and vitamin C (MAC) for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Blood

2005;106:720A–1A.

10. Berenson JR, Matous J, Ferretti D, et al. A phase I/II study of arsenic trioxide, bortezomib, and ascorbic acid in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma.J Clin Oncol2006;24:7611.

11. Qazilbash MH, Davis MS, Ana A, et al. Arsenic trioxide with ascorbic acid and high-dose melphalan: A new preparative regimen for autologous hemato-poietic stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Blood 2005;106: 338A–9A.

12. Qazilbash MH, Jindani S, Gul Z, et al. Arsenic trioxide with ascorbic acid and high-dose melphalan for autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma.Biol Blood Marrow Transplant2007;13:9S–10S. 13. Wu KL, van DJ, Beksac M, de Knegt V, Sonneveld P. Treatment with arsenic

trioxide, ascorbic acid and dexamethasone in advanced myeloma patients: preliminary findings of a multicenter, phase II study.Blood2005;106:367B. 14. Qazilbash MH, Saliba R, Parikh G, et al. Arsenic trioxide with ascorbic acid and

high-dose melphalan is safe and effective for autotransplantation for multiple myeloma.Blood2007;110:942.

15. Hofmeister CC, Jansak B, Denlinger N, et al. Phase II clinical trial of arsenic trioxide with liposomal doxorubicin, vincristine, and dexamethasone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma.Leuk Res2008;32:1295–8.

16. Baz R, Kelly M, Reed J, et al. Phase II study of dexamethasone, ascorbic acid, thalidomide and arsenic trioxide (DATA) in high risk previously untreated (PU) and relapsed/refractory (RR) multiple myeloma (MM).J Clin Oncol2006;24: 17535. 17. Berenson JR. A phase I/II multicenter, safety and efficacy study of combination

treatment with melphalan, arsenic trioxide and vitamin C (MAC) in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma.Blood2004;104:659A. 18. Gesundheit B, Shapira MY, Resnick I, et al. Trisenox (arsenic trioxide) in the

treatment for multiple myeloma after bone marrow transplantation. Blood

2005;106:365B.

19. Bahlis NJ, Cafferty-Grad J, Jordan-McMurry I, et al. Feasibility and correlates of arsenic trioxide combined with ascorbic acid-mediated depletion of intracellular glutathione for the treatment of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma.Clin Cancer Res2002;8:3658–68.

20. Birch R, Schwartzberg LS, Schnell FM, Tongol JM, Prill SJ. A phase II study of arsenic trioxide (ATO) in combination with dexamethasone (Dex) and ascorbic acid (VITC) in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Blood

2003;102:386B.

21. Borad MJ, Swift R, Berenson JR. Efficacy of melphalan, arsenic trioxide, and ascorbic acid combination therapy (MAC) in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma.Leukemia2005;19:154–6.

22. Dey S, Gupta P, Chitalkar PG, Mukhopadhyay A. Arsenic trioxide for treatment of multiple myeloma.Ann Oncol2007;18:ix178–182.

23. Munshi NC, Tricot G, Desikan R, et al. Clinical activity of arsenic trioxide for the treatment of multiple myeloma.Leukemia2002;16:1835–7.

24. Rousselot P, Larghero J, Arnulf B, et al. A clinical and pharmacological study of arsenic trioxide in advanced multiple myeloma patients. Leukemia

2004;18:1518–21.

25. Berenson JR, Matous J, Swift RA, et al. A phase I/II study of arsenic trioxide/ bortezomib/ascorbic acid combination therapy for the treatment of relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma.Clin Cancer Res2007;13:1762–8.

26. Hussein MA, Saleh M, Ravandi F, et al. Phase 2 study of arsenic trioxide in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol

2004;125:470–6.

27. Berenson JR, Boccia R, Siegel D, et al. Efficacy and safety of melphalan, arsenic trioxide and ascorbic acid combination therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: a prospective, multicentre, phase II, single-arm study.Br J Haematol2006;135:174–83.

28. Abou-Jawde RM, Reed J, Kelly M, et al. Efficacy and safety results with the combination therapy of arsenic trioxide, dexamethasone, and ascorbic acid in multiple myeloma patients: a phase 2 trial.Med Oncol2006;23:263–72. 29. Wu KL, Beksac M, van DJ, et al. Phase II multicenter study of arsenic trioxide,

ascorbic acid and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma.Haematologica2006;91:1722–3.

30. Rajkumar SV, Greipp PR. Prognostic factors in multiple myeloma.Hematol Oncol Clin North Am1999;13:1295–314, xi.

31. Wen J, Cheng HY, Feng Y, et al. P38 MAPK inhibition enhancing ATO-induced cytotoxicity against multiple myeloma cells.Br J Haematol2008;140:169–80. 32. Lunghi P, Giuliani N, Mazzera L, et al. Targeting MEK/MAPK signal transduction

module potentiates ATO-induced apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells through multiple signaling pathways.Blood2008;112:2450–62.

33. Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Caravita T, et al. Oral melphalan and prednisone chemotherapy plus thalidomide compared with melphalan and prednisone alone in elderly patients with multiple myeloma: randomised controlled trial.

Lancet2006;367:825–31.

34. Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster M, et al. Extended follow-up of a phase 3 trial in relapsed multiple myeloma: final time-to-event results of the APEX trial.Blood2007;110:3557–60.

35. Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster MW, et al. Bortezomib or high-dose dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2005;352: 2487–98.

36. Dimopoulos M, Spencer A, Attal M, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma.N Engl J Med2007;357:2123–32. 37. Richardson PG, Blood E, Mitsiades CS, et al. A randomized phase 2 study of

lenalidomide therapy for patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma.Blood2006;108:3458–64.

38. Weber DM, Chen C, Niesvizky R, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma in North America.N Engl J Med2007;357:2133–42.