International

organizations

and

the

future

of

education

assistance

Stephen

P.

Heyneman

1,*

,

Bommi

Lee

VanderbiltUniversity,Cambridge,MD,USA

1. Introduction

Educationhasbeenfoundtohavetwocategoriesofinfluences. Intermsofmonetaryinfluences,thehigheranindividual’slevelof education,thelesslikelytheywillbeunemployedorinpoverty, andthemorelikelytheywillhavebetteradvantagesintermsof incomeandincomesecurity.Moreover,whatistrueofindividuals isalsotrueofcommunitiesandnations.Intermsofnon-monetary influences,educationhasbeenfoundtoaffectpersonalhealthand nutrition practices, childrearing and participation in voluntary activities.Italsoinfluencestheefficiencyof public communica-tions andthedegreetowhich adultsseek newknowledgeand skillsoveralifetime(Blaug,1978;Schultz,1982;McMahon,1999). Howcommunitieslearn,therefore,isaprincipalingredientof theirdevelopment.Inmoderneconomies,schoolsanduniversities are theprimary means by which knowledge is passed to new generationsandhow newknowledgeissystematically incorpo-rated(WorldBank,1995).

Education was first included as a component of foreign assistanceintheearly1960s.Initially,educationaidwasdeployed tosupportworkforcedevelopmentplans,soprogrammes empha-sizedvocationaltraining,engineeringeducationandimmediately applicable workskills. Infrastructure investments such as high-ways, railroads, dams, bridges and agricultural and industrial machinerywerestillthemostimportantprioritiesofdevelopment aid,buttheyneededskilledmaintenance.Educationaidwasaway

tomakesurethenecessaryskillswerelocallyavailable (Heyne-man,2004a).

Bythe1980s,educationaidhadgrowntoincludeprimaryand secondaryeducation,humanitiesandsocialsciences,professional educationandeducationresearch.Theshiftwastriggeredbythe WorldBank’spublicationofaneducationpolicypaperin1980that diversifiedtheanalyticmodelsforassessingeducationoutcomes beyond forecasting manpowerneeds to include calculatingthe economicratesofreturnoneducationinvestments(WorldBank, 1980; Heyneman, 2009, 2010). A common finding was that primaryeducationhadthehighesteconomicreturns,leadingto callsforpublicfinancingtoshiftfromhighertoprimaryeducation, andfor highereducationtobefinancedbyraisingprivatecosts throughtuition(Psacharopoulosetal.,1986).

That was followed in the 1990s by an approach known as ‘education for all’, with strong emphasis placed by donors on primary education (UNESCO, 2007). This approach has since becomethedominantparadigmofeducationaid,withsignificant and often negative consequences for the sector as a whole (Heyneman,2009,2010,2012a).

2. Institutionalarchitecture1

ForeignassistancebeganafterSecondWorldWarforreasonsof reconstruction,politicalinfluenceandaltruism.Ingeneralforeign aidbeganwiththeintroductionoftheMarshallPlanbytheUnited States, a transfer of US$13 billion between 1948 and 1952 to supportthereconstructionof14Europeancountries,withtheUK receiving the highest percentage (24 per cent) and Norway ARTICLE INFO

Articlehistory:

Availableonline22January2016 Keywords:

Educationaid Aideffectiveness Multilateral Bilateral

Officialdevelopmentaid

ABSTRACT

Educationbegantobeincludedasacomponentofforeignassistanceintheearly1960sasitisaprincipal ingredientofdevelopment.Anumberofmultilateralandbilateralagencieswereestablishedaroundthis timetoimplementvarioustypesofaidprogrammes;however,theireffectivenessisconstantlybeing questionedand challengeddue toavariety ofproblems.This paperreviewsthepastand current activitiesofbilateral,multilateralorganizationsandprivatedonorsineducationaid,examinestheir effectiveness,discussesmajorproblemsinimplementingeducationalprogrammesandsuggestswaysto improveaidineducation.

ß2015UNU-WIDER.PublishedbyElsevierLtd.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

* Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:s.heyneman@gmail.com(S.P.Heyneman). 1

Professor(Emeritus). 1

AdaptedfromHeyneman(2012b).

ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

International

Journal

of

Educational

Development

j ou rna l h ome pa ge : w ww . e l se v i e r. co m/ l oc a te / i j e dude v

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.11.009

0738-0593/ß2015UNU-WIDER.PublishedbyElsevierLtd.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/ 4.0/).

receiving the highest allocation in per capita terms (US$136/ person) (Moyo, 2009: 12). The first multilateral organizations consistedofUNESCO,WHO,UNICEFandtheWorldBank(Singh, 2011).CurrentmajormultilateralaidprovidersincludetheWorld Bank (US$1.7 billion), UNICEF (US$709 million), the Asian Development Bank (US$647 million) and the Inter-American Development Bank (US$465 million), JICA (US$185m), USAID (US$1.3billion),DFID(US$960million)(SeethetableinannexII). In 2010, approximately three-fourths of education aid flows throughbilateralorganizationsand 26 percentthrough multi-laterals(OECDCRSdatabase).Ofthemultilaterals,theWorldBank historicallyhasallocatedthelargestportion,theEUallocatesthe secondlargest portion (OECD CRS). In terms of its size within organizationalbudgets, educationaidisgenerally around4per cent:4percentattheWorldBank(Table2)andtheInter-American Bank,4.8percentattheAsianDevelopmentBankand5.8percent fromtheEU.Surprisingly,perhaps,theAfricanDevelopmentBank allocatesthelowestportiontoeducation,atjust0.9percent.

In1961,PresidentJohnF.Kennedyexplainedforeignaidtoassist low-incomecountries‘notbecausethe communistsaredoingit, butbecauseitisright’(quotedinSartoriusandRuttan1988:4). However,overtime,foreignaidfrequentlycombinedpoliticalwith humanitarianmotives.Ingeneralthepoliticalmotivesof multilat-eralorganizations associated withthe United Nations were less manifestinpartbecauseprojectsandstrategieshadtobeaproduct of consensus across multiple interests, including those of aid recipientcountriesaswellasthoseofdonorcountries.Ontheother hand, because bilateral agencies reflected national foreign aid priorities,bilateralassistance,thenationaloriginofconsultantsas wellasthepoliticalandeconomicobjectivestendtoreflectthose ofthe donor. These tendenciesare notuniform however;some bilateralagencies tend tobequite agnostic with respectto the originsof consultants whileothers tend tobe quite restrictive. However,nobilateralagencyallowsitsassistancetobedirected towardhumanitarianneedsalonewithouttheinfluenceofpolitical oreconomic interest.Thesecharacteristics, moreover, pertainto newbilateralorganizationsinChina,Russia,KoreaandBrazilaswell astheolderonesinEuropeandNorthAmerica.

Bilateralorganizationsarethosewhosedevelopmentprojects are arranged country-by-country. The assistance which flows throughbilateralorganizationsisdistinctfromthatwhichflows throughmultilateralorganizations.Bilateralassistanceispartofa

donor nation’s foreign policy. For instance, the US, in 2004, allocatedthemajorityofitsbilateralassistancetoIraq,Israel,West BankandGaza,Egypt,JordanandAfghanistan(OECD-DAC).Also, among the top ten recipients of French bilateral aid, seven countriesareeitherFrenchspeakingcountries(Congo,Rep,Coˆte d’Ivoire,Senegal),orFrenchterritories(Mayotte),ormembersof theOrganisationInternationaledelaFrancophonie(OIF)(Morocco, Vietnam,Lebanon)(OECD-DAC)

Bilateraleducationaidhasexpandedduringthe1960sto1990s. IttotalledUS$3.4billionin1965,touptoUS$6billionin1980,and thentoUS$3.9billion(constant1994US$)in1995(Mundy,2006). However,Fig.1belowshowsthattheincreasewasslowsincethe late 1990s. Fig. 1 demonstrates that in 2011, education aid accounts for US$11 billion (constant 2010 US$) worldwide, or about8percentoftotalofficialdevelopmentassistance(ODA).

Amongnationalaidorganizations,majordonorsincludetheUS AgencyforInternationalDevelopment(US$1.3billion), theUK’s DepartmentforInternationalDevelopment(US$960million)and Japan’sJICA(US$185 million).However,theportionof develop-ment aid dedicated to education by western aid agencies is relativelysmall,atjust3percentforbothUSAIDandNorway’s developmentagency,NORAD,and4percentforSweden’sSIDA.By contrast,educationismoreofanaidpriority formanybilateral agenciesinAsia,withJICAdevoting14percentofitsaidbudgetto education,Australia’sAusAid17percentandSouthKorea’sKOICA 25percent.

WhydoJapanandSouthKoreaemphasizeeducationintheir foreignaid? Botheconomies have emergedas a result oflarge investmentsinhumancapital.Butoneexplanationatleastasfaras Japanisconcerned,isnotbeingassociatedwith‘tryingtoselltheir products’.Educationhasareputationofbeinglesscontroversial than thesectors.Emphasison educationmay lowertherisk of criticismofaidservingdonor’sself-interest.

Bilateralorganizationstendtoemphasizeaspectsofeducation aidthatareparticularlypopularorstrategictodomesticinterests. Thesemayincludeparticularareas,suchastechnicalschoolsor folk development colleges, as well as particular reforms and innovations,suchasbilingualeducation,televisededucationand diversifiededucation(Heyneman,2006a).

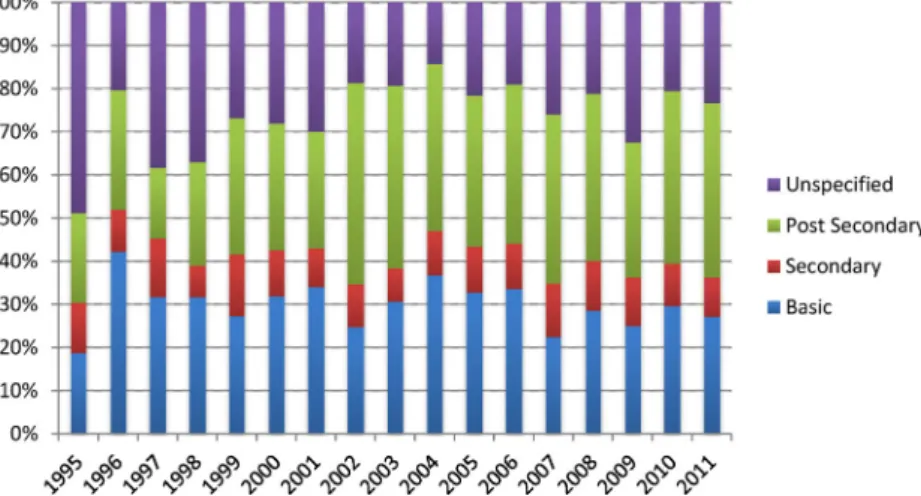

Though basic education continues to dominate education politicalobjectives,fundingisalsodirectedtowardsawidevariety of other priorities. These include secondary education, teacher training, adult education and literacy, science education, voca-tional skills and higher education (OECD-CRS). In many cases, privatefoundationsandnongovernmentalorganizationsfocuson particularareas.Forinstance,theFordandCarnegieFoundations haveconcentrated onhighereducation,whiletheOpen Society Institute(sometimecalledtheSorosFoundation)hasfocusedon primary and secondary education, and on civics education in particular.Manyorganizationsfundparticularareasofeducation

Table1

TotalODAtoeducationfrom1995to2011.

Year TotalODA TotalODAtoeducation %EducationalODA

1995 57,556.47 2,888.24 5 1996 63,690.44 4,325.83 7 1997 60,510.82 4,682.08 8 1998 70,059.01 4,844.90 7 1999 77,356.45 6,403.74 8 2000 83,743.78 6,376.74 8 2001 84,861.80 6,456.63 8 2002 97,168.91 7,929.27 8 2003 114,455.73 9,128.38 8 2004 115,867.07 10,828.82 9 2005 141,228.59 8,489.96 6 2006 146,401.38 11,529.41 8 2007 135,025.36 11,611.16 9 2008 155,755.59 11,485.99 7 2009 161,627.96 13,408.07 8 2010 163,512.42 13,344.09 8 2011 148,906.84 11,030.09 7

Note:Constantprices2010US$million.Alldonors’commitmenttodeveloping countriesreportedtoOECD.

Source:ThefiguresfortotalODAarederivedfromOECD/CRSdatabaseandthe amountisdifferentthanthatfromtheofficialEFAGlobalMonitoringReportdueto differentmethodofcalculation.Thus,theportionofeducationODAisslightly smallerthantheofficialfiguresinEFAGlobalMonitoringReport.

0 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.06 0.07 0.08 0.09 0.1 Percentage of educaonal ODA

that correspond to their institutional mission: The Food and AgricultureOrganizationfundsruraleducation,forinstance,and theWorldHealthOrganizationfundseducationrelatedtohealth. Charitable foundations actively participate in international education.Theysupplygoodsandservices,experimentwithnew institutions,lobbyfornewpoliciesandgeneratenewinitiatives. About 80 per cent of them are American (Heyneman, 2005) becausecharitablegivingintheUSissupportedbythetaxcode and there is a relatively low marginal tax on income which facilitates personal wealth. American foundations tend to be largerandolderthanthoseelsewhere.

Religious philanthropy2 remains a common conduit for education.Thesecanbefinancedeitherthroughpublicorprivate resources.Publicschoolsmanagedbyreligiousorganizationsare commonthroughoutLatinAmerica,sub-SaharanAfrica,andAsia. ForthemostparttheseareaffiliatedwithChristianchurches.But intheMiddleEastandNorth Africa,and inpartsoftheformer SovietUnion,schoolscanbeaffiliatedwithmosquesandinSouth Asia,withBuddhisttemples.Whereverschoolsaremanagedby religiousorganizationsitiscommonforparentsandcommunity leaderstogarnersupportfortheirprogrammesthroughvoluntary donationsoflabourand capital.Catholicsoftenprovide interna-tionalassistance through Caritas;Protestantsthrough Christian Aid and World Vision. Among Muslims, the Zakat (charitable donations)isassumedtobeabout2.5percentofanindividual’s annualincomeandhasfinancedhospitals,schools,publicwater supplyandotherpublicservices.Religiousnorms,calledWaqf,are theKoran’smethodforallocatingpersonalwealthproperly,which areoftenoverseenbystateinstitutions.InthecaseofPakistan,for instance, the central government ministry of Waqf manages charitableactivities(Richardson,2004:156).

2.1. Non-DACdonors

In recent years, some new donor countries have become providers of education assistance to middle and low-income

countries.Dotheyhaveparticularcontributionstomake?China’s contribution, for example, has been limited to (i) Confucius institutes(aroughequivalenttoUSISortheBritishCouncil),(ii) scholarships to study in China; (iii) construction of individual schoolsand(iv)stand-aloneeducationprojects(Nordtveit,2011). King(2010)notesthatChina’strainingroleinKenyahasmetwith considerabledemandbyKenyanstolearnChineseandisclosely related to the growth of Chinese business and foreign direct investment.TheAsiaFoundation(2014)pointsoutthateducation aidisrepresentativeof‘softpower’,ameansbywhichcountries mighthaveaninfluencebutwithalowriskofbeingaccusedof ‘economic imperialism’. Is education special because it is now consideredbynewdonorsinAsia?

The education sector is the second largest in Korea’s aid portfolio (Watson, 2012). Chung (2013) points out that vocationaleducationisthepredominantpurposewithin educa-tion assistance, which underpins Korea’s intention to utilize education for its instrumental value. He speculates that the lack of education policy experts with developing country experience,thelessonsofKorea’sownhistoryofusingvocational educationtospureconomicgrowth,andthefactthatvocational education is relatively ‘safe’ from cultural sensitivities, all help underpin South Korea’s education policies and priorities (Chung,2013).

ThereiseducationassistancetoofromtheRussianFederation. However, officialstatisticsfromRussiaarenotbrokendown by sector (Curry, 1989; Maximova et al., 2013), so other than to suggest thatcurrentassistanceis largelypredicatedon concep-tions of education duringthe Soviet era(Takala and Piattoeva, 2012),itisdifficultassessitsdirectionorimpact.However,Russia hascreatedatrustfundattheWorldBanktitledRussiaEducation AidforDevelopmentTrustFund(READ)whosepurposeistoassist low-incomecountriesindevelopingstudentlearningassessment including their participation in TIMSS and PISA (READ Annual Report 2013). Thereare many possiblereasonsforthis specific interest.OnemightbetoexposeRussiananalyststothelogistical details ofachievementsurveys.Anothermight betoencourage countries in the ‘near abroad’ to participate in achievement surveys.Insum, newdonors intheeducationsectortodatedo not seemtohave brokennewground orledintounanticipated directions.

Table2

Foreignassistancetoeducationfromselectedmajormultilateralandregionalorganizations. Majorprioritiesineducation Yearof

establishment Monetarycommitment ineducationUS$mn %ofoverall activitieson education Source EU/EuropeAid Post-secondaryeducation, educationlevelunspecified, basiceducation

1949 770.238*

5.8 2011AnnualReportEuropeanCommission

AsianDevelopmentBank Improvingstudentresultsand

completionrateineducation, financingforhighereducation

1966 647 4.8 ADBAnnualReport2011,AsianDevelopmentBank

AfricaDevelopmentBank Highereducation,science,

technologyandvocationaltraining

1964 6.13**

0.9 2011AnnualReport,AfricaDevelopmentBank-Africa DevelopmentFund

Inter-AmericanDevelopmentBank Primary,secondaryeducation,

qualityeducation

1959 465 4 2011AnnualReport,TheYearinReview,Inter-American

DevelopmentBank WorldBank

Basiceducation,highereducation, vocational,in-servicetraining, pre-school

1944 1,733 4 WorldBank,AnnualReport2011,YearinReview,

WorldBank

Totalamount:3.98UAmillions.

Source:Createdbyauthorsbasedonannualreportsofeachorganization. *Notesfor1Euro=US$1.23.

**Notesfor1UA=1.54(asof2010).

2

Religiousphilanthropyshowsreligiouspurposesastheirmissionstatement, whereascharitablefoundationsdonotexplicitlyshowreligiouspurposeintheir missionstatements. Save the Children and CARE are examples ofcharitable foundations.Caritasisanillustrationofareligious(Catholic)philanthropy.

3. Theeffectivenessofeducationaid

Thedoubtsandconcernsovertheeffectivenessofeducationaid mirrorthosewhichpertaintoaidmoregenerally.Likeaidingeneral, theassumptionhasbeenthatitwouldbemoreeffectiveif(i)spentin verypoorcountries,(ii)incountrieswithgoodpoliciesandstrong institutions, and (iii) in countries with strong mechanisms of allocation(Klein andHarford: 2005:36-7). Interms ofbilateral donors,agencies with reputations foreffectively delivering pro-gramme for the intended purposes (the United Kingdom and Denmark)mayoutrankagencieswithreputationsforbeingtheleast effective(JapanandtheUnitedStates)(KleinandHarford:39).

Therearemanyillustrationsofaidwaste.Inonecase,lessthanone percentofassistancetoaministryofhealthwasfoundtoactually reachhealthclinics(Collier,2007:102);11percentofaidhasbeen foundtoactuallyfinancethemilitary(Collier,2007:103);andwhen allocatedonthebasisofexantepolicyconditionality,donorshave beenfoundtoallocateaidinspiteofthelackofcommitmentonthe partoftherecipient(Collier,2007:108).Somehavedrawnalink betweenaidandcorruptionbothintherecipientcountriesandinthe donoragency(Kleesetal.,2012;Cullen,2008:110;Heynemanetal., 2008),leading toa distrustof international financialinstitutions (Cullen, 2008: 118). Some,including Africans (Moyo,2009)have suggestedthataidisdysfunctional(Calderisi,2006;Collier,2007:99) andshouldbereplacedbytrade(Easterly,2006).

Aid effectiveness is difficult to measure (Cullen, 2008: 24). Evaluations may assess particular projects or programmes and sometimesthesemayleadtoclearconclusions3.Someagencies havebeen foundtohave beenmore effectivein implementing projectsthanotheragencies.Effectiveimplementationseemsto beparticularlythecasewithBritain,but lesssowithrespectto NorwayandtheUS(seeTable3).

Channingetal.(2011)arguethatgeneraldevelopmentaidhelps tostimulategrowthandreducepovertythroughphysicalcapital investments and improvements in health. Focusing on aid to primaryeducation,BirchlerandMichaelowa(2013)arguethataid hasledto‘modestbutnon-negligible’improvementinenrolment butnotnecessarilytoimprovedlearning.Howeverithas proven difficult toassess the effectiveness of education aid for several reasons.BirchlerandMichaelowastrugglewiththepossibilityof ‘reversecausality’,theproblemthathigherenrolmentmayattract largeraidratherthantheotherwayaround.Theyarealsochallenged byproblemsofinter-sub-sectorcomplementarities.Theybeginby treatingaid to other parts of the education sector as a sign of ‘inefficiency’butintheendtheyacknowledgethataidtosupport highereducationmayaugmenttheperformanceatlowerlevels4.

Otherdifficultiesincludethepossibilitythateducationaidhas supplantednormal governmentfundingratherthanaddedtoit andtheproblemthattheremaybecomplexitiesofsequencingand thresholds.Forinstance,Collier(2007:100)suggeststhatratesof primary schoolcompletion climbed to100 per centof theage cohortin Korea,MalaysiaandThailandin spiteofthefactthat thesecountriesreceived noaidforprimaryeducation,andthat completionrateshaveincreasedsubstantiallyinIndiaandBrazil whereexternalassistanceisasmallfractionofdomesticeducation expenditures.Theconclusionisthat,inmanycircumstancesaidis unnecessarytoachievehigheducationoutcomes.Inaddition,even inlow-incomecountrieshighlydependentonaid,theimpactofaid oneducationoutcomesismodestbutnon-trivial.Whilethatasa resultmaybesufficientoutcomeforsomewhoareemployedinthe aidindustry,itmaynot provesufficient forpublictaxpayersin donor countries who have multiple alternative uses for the allocationoftheirresources.

Ausefulindicatorofaidoutcomesmightbethestabilityofan aid-receivingcountry’sinstitutions.Thismayincludethedegreeto which courts can remain independent; the degree to which electionscanbeheldfairly;thepossibilitythatuniversityentrance examinations can be administered withoutcorruption (Heyne-man, 2004b; 2002/3). For example, in Malawi, a country that receives high levelsof aidand has stable institutions, primary schoolenrolmentrateshaveclimbedfrom21percentin1975to 66percentin2010(Figs.10and11).However,inLiberia,acountry withweakinstitutions,completionrateshavefallenfrom69per cent in 1976 to 62 per centtoday, in spite of highaid levels. Secondaryschoolenrolmentsuggestsasimilarpattern.Significant increasesareexperiencedbycountrieswithnoaid,withlowaid andwithhighaidiftheyhavestronginstitutions.Butsecondary schoolenrolmentratesremainflatorincreaseatalowerratein high-aidcountrieswithweakinstitutions.Thislackofaclearlink betweenaidandeducationoutcomeshasraisedquestionsastoits effectiveness.

4. Researchontheeffectivenessofaidoneducational outcomes

Despite the lack of data and difficulties to measure the effectiveness of aid, quite a large body of literature exists on assessing aid on economic growth. Unlike the researchon aid effectivenessoneconomicgrowth,whichbeganinthemid-1980s, therearefewstudiesonaideffectivenessoneducationaloutcomes. However, it is important to note that many of the successful interventionswereeducationalprogrammes.Studiesthatanalyse the effect of educational interventionsin developing countries have found positive effects. Duflo (2001), who analyses aid-financedprimaryschoolexpansioninIndonesia,findssubstantial increases in educational attainment and higher wages for the graduates. Evidence from randomized experiments in India showedthataremedialeducationprogrammeincreasedaverage testscoresoftreatmentschoolsandacomputerassistedlearning

Table3

Rankingofdonorsonaideffortandquality.

Aidqualityindexes Donorcountry Aidefforta

Povertyelasticity(DollarandLevin,2004) Policyelasticity(DollarandLevin,2004) Composite(Roodman,2004)

Denmark 1 1 1 3 UK 3 3 2 1 Norway 2 2 3 5 France 4 5 6 2 US 6 4 5 4 Japan 5 6 4 6

Source:BasedonKleinandHarford(2005),DollarandLevin(2004)andRoodman(2004).

aAideffortismeasuredbyODAasapercentageofthedonorcountry’sGNI.ThedataarefromtheWorldBank(2004).

3See,forexample,Glewweetal.(2004),Heynemanetal.(1984),Pandeyetal. (2011),Glewwe,(ed.,2014),Oketchetal.(2010).

4

Development specialists have often assumed that assistance to primary educationshouldtakeprecedenceoveraidtohighereducationwheninfactpublic investmentsinhighereducationintheUnitedStateshelpedstimulatedemandfor primaryandsecondaryeducation(Bowman,1962).

programme focusing on math increasedchildren’s math scores (Banerjeeetal.,2005).Eventhemostseverecriticsofforeignaid, likeEasterly,acknowledge positive effects ofeducational inter-ventionprogrammes.

Thereareanincreasingnumberofstudiesthatassesstheimpact of educational intervention in developing countries through randomized controlled trials or quasi-experiments. Though the interventionprogramsarenotalwaysfundedbyforeignaid,itis crucialtonotesomelessonslearnedfromthesestudies.Anumber of studies have systematically reviewed and attempted to find implicationsforeducationpoliciesfromthestudiesofrandomized control trials, quasi-experiments/natural experiments (Glewwe, 2002;GlewweandKremer,2006;KremerandHolla,2009;Glewwe et al., 2014; Masino and Nino-Zarazua, 2015). These studies generally concluded that reducing the cost of education and providingschool-basedhealthprogramsincreasedschool partici-pation (Glewwe and Kremer, 2006; Kremer and Holla, 2009), however,the supply-side interventionsthemselves arefound to beineffectiveinimprovingeducationqualityandaremosteffective whenthey are complemented with communityparticipationor incentiveprograms(MasinoandNino-Zarazua,2015).

Findingsfrommeta-analysisoverallalsoshowsimilarlessons though some interventions have mixed evidence to draw conclusion (Petrosino et al., 2012; Krishnaratne et al., 2013; McEwan, 2014). For increasing schoolparticipation, the condi-tional cash transfer programs, new schools and infrastructure buildinginterventions as well as school feeding programs had positiveeffect(Petrosinoetal.,2012;Krishnaratneetal.,2013). Krishnaratneetal.(2013)‘sstudyfoundthatbetterinfrastructure buildinghad positive impacton increasingboth student atten-danceandlearningoutcomes.However,theanalysesshowedthat interventionstoreduceschoolingfeesandsubsidyprogramsdo notnecessarilyimprovedstudentlearningoutcomes(Krishnaratne etal.,2013;McEwan,2014).Teachingresourcessuchasadditional teachersandcomputer-assistedlearningwerefoundtobemost effectiveonlearningoutcomes(Krishnaratneetal.,2013;McEwan, 2014). Other interventions such as merit-based scholarships, school-based management, and information to parents on schooling can also have positive impact on learning outcomes butevidencewasnotstrong(Krishnaratneetal.,2013).

Theevidenceoneffectivenessisbecomingincreasinglymore precise over time. In spite of the improvement in precision however,twoproblemshaveemerged.Thefirstisthatprecision doesnotguaranteeinsightfulresults.Inonesummaryarticlethe mainconclusionshavebeenthata‘‘fullyfunctioningschool(desks, roofs,walls,andalibrary)is‘conducivetostudentlearning’’and that ‘‘teacher absencehas a clearnegative effect on learning.’’ (Glewweetal.,2014,p.47).Onewonderswhysuchhighpowered expertiseandexpenseisneededtoreachalong-standingandwell knownresult.

Theotherproblemhastodowiththelimitsonevidence-based policy.Highqualityevidencecannotbesimplydefinedbytheuse ofquasi-experimental(i.e.regressiondiscontinuitydifferencesin differences) or experimental studies such as randomized con-trolledtrialmethodsbecausetheassociationsarenotsostraight forward. They cannot control for the ‘‘totality of individual characteristics and the broad range of contextual factors that may affect program development and its outputs. economic approachesaregoodforidentifyingoutcomes,butnotnecessarily the social mechanisms behind the relationships (Verger and Zancajo2015,p.368andp.370).Theselimitsarerecognizedby manyeconomists,but thecorrectbalancebetweenprecisionon outputsandexplanationsofwhythoseoutputsoccuris undevel-oped(Heyneman,2014;Burde,2014).

Itisalsorelatively recentthat economistsbegantoconduct macro-levelstudiesontheeffectivenessofeducationalaid.Many

ofthestudiesfindpositiveeffectofaidoneducationaloutcomes; however,themagnitudeoftheeffectismodest.Michaelowaand Weber’sstudy(2006)examinestheimpactofaidforeducationon primaryenrolmentratesovertimeineightylow-incomecountries. Theyconducteda dynamic panelanalysis usingprimaryschool enrolment,ODAandothercountry-leveldatafromtheWorldBank. Theirresultswerepresentedintwodatasets:along-termstructural panel (five-year averages, 1975–2000) and a short-term annual panel(1993–2000).Theyfindapositiveoveralleffectof develop-mentassistanceonprimaryenrolment;however,educationalaid wasmoreeffectivewhencoupledwithgoodgovernance.

AnotherMichaelowaandWeber’sstudy(2008)alsoexamines theaideffectivenessonprimary,secondaryandtertiaryeducation enrolments. Theyusedashort-termannualpanelfrom1999to 2004,andapanelstartingintheearly1990sto2004.Theirstudy shows some positive effect of aidat all three levels (primary, secondaryandtertiary)ofeducation;however,theoveralleffects areboundtobequitelow.

Dreheretal.(2008)analysetheimpactofaidoneducationfor almost100countriesover1970to2004.Theyfindthathigherper capita aid for education significantly increases primary school enrolment, while increased domestic government spending on education does not. This result was robust to the use of instrumentstocontrolfortheendogeneityofaid,andthesetof controlvariablesincludedintheestimation.

However, Christensenetal’s, study(2012) showsa negative effectofeducationaidonenrolment.ThestudyusesbothODAand nonODAdatatotesttheeffectivenessofprimaryeducationaidon primaryschoolenrolmentrate,andthedatacover109low-and low-middleincomecountriesfrom1975to2005.Resultsfroma latent growth model and panel regression models show that primaryeducationaidisnotrelatedtoprimaryenrolmentratesin astatisticallysignificantway.

Thus,theresearchresultsonmeasuringtheimpactofaidon educational outcomesare inconclusive. Although more studies showamodestpositiverelationshipbetweeneducationaidand enrolment,theestimatedeffectsareratherlowandaresensitiveto differentmodelspecifications(MichaelowaandWeber,2006).The relationship between aid and economic growth is much more contestedthanaidoneducationoutcomes.Implicationsfromthe effectofaidon economicgrowthresearchis thatwhenastudy assumesalinearrelationshipbetweenaidandgrowth,thenaidis likelytohavelittleornoeffect.However,studiesfoundthataid worksbetterincountrieswithstrongerpoliciesandinstitutions. These conditional studies have gained much popular support, suggestingthataidallocationcanmakeasubstantialdifference. Also,studiesthatassumediminishingreturnsofaidandallowfor heterogeneity of aid tend to find a positive and significant relationship(AsieduandNandwa,2007;MichaelowaandWeber, 2006).

Futureresearchmightfocusonspecificareasinwhichaidcan haveadirecteffect.Theimpactofeducationaidinparticularis more likely to be observed in the long term. Data should be available on details of programmes,such as types of aid(e.g., trainingprogramme,budgetsupport,grantorloan,etc.),sothatit can be differentiated among programme characteristics. Since therearemajorconcernsregardingeducationquality,thereisan increasingneedformoreandbetterdataoneducationalquality suchaslearningoutcomes,whichcurrentlyarerestrictedtoupper middle-incomecountries.Manychildrencompleteprimaryschool withoutbecomingliterate(UNESCO,2012).Therefore,itiscrucial tomeasurelearningoutcomestoseetheeffectofeducationalaid, hencetheneedforachievementassessments.Butmost conspicu-ous is the absence of aid’s impact on the social outcomes of education––better citizenship, honesty, and social cohesion (Heyneman,2002/3).

More empirical studies are needed for monitoring and evaluating aid projects and for future policymaking, as many policydecisionsareoftenbasedonlimitedevidence(Banerjeeand He,2008).However,weshouldnotrestrictourdecisiontohard evidenceonly,aseducationaloutcomesshouldbeobservedinthe longrun. Longitudinal datashould be idealto conduct further research. It is also necessary to consider the deeply rooted problems of foreign aid in the recipient countries, such as corruptionandaculturethatdoesnotvalueeducation.

5. Problemswitheducationaid

While it is difficult to assess the overall effectiveness of educationaid,itiseasiertoidentifytheproblemsthatundermine effortstosuccessfullyimplementtheprogrammesitfunds. 5.1. Institutionalimbalanceandoverlap

Thereisbothimbalanceandduplicationinthemandatesofthe manyinstitutionsinvolvedineducationaid.Somehavemandates coveringonly thewealthier partsof theworld (such asOECD) while others have regional mandates in Africa, Asia and Latin America, creating funding imbalances that do not necessarily respondtoareasofneed.Stillotherorganizations,suchasUNESCO, haveworldwidemandates,butareburdenedbyweakgovernance andadisconnectbetweenthefewmemberstatesthatpayforthe organizationandthemany othersthat voteon a one-vote-per-countrybasis on how the budget is allocated. This disconnect betweenthosewhopayandthosewhobenefitmakesitdifficultto setprioritiesormaintainprofessionalstandards.

Meanwhile,lackofcoordinationbetweeninstitutionsatvarious levelsofaiddistributionleadstoduplicationandattimeseven conflictofaidefforts.InKyrgyzstan,theAsianDevelopmentBank andtheWorldBankbothlaunchededucationtextbookprojectsin thesamecountry,withtheresultbeingthatonepartofthecountry usedADB-sponsoredtextbooks,whiletheotherusedWorld Bank-sponsoredtextbooks.Projectpreparation,appraisal,stafftraining, technicalassistanceandevaluationwereconductedseparately,in spiteofthefactthattheprojectimplementationauthoritieswere situatedonlyminutesapart.

5.2. Informationcapacity

Education systems cannot perform professionally without reliableinformation, but there is a wideninggapin the ability ofcountriestoprovidethisinformation,withtheresultbeingthat inmanyinstanceseducationdataareunreliable(Heynemanand Lykins,2008).Forexample,therearenoaccuratecountsofschool attendance by student age, no accurate information on unit expenditures,littleevidenceoftrendsinacademicachievement andwidevariationintheirqualityfromonepartoftheworldto another.Asa result,itis difficulttomapeducationprogressin termsofenrolment,completionandefficiency(Heyneman,1999). 5.3. Weakeneddomesticinstitutions

Insomecases,insteadofstrengtheningdomesticinstitutions, aidcanactuallyweakenthem(Heyneman,2006a).Policydecisions canbelefttoexternalauthoritiesasa wayofavoidingdifficult decisionsand controversy,since it is politically saferto blame external authorities if things go wrong. In the 1960s, it was commontosuggestthatlocalauthoritiesdidnothavethetechnical experience tomake complex policydecisions. Today, however, suchclaimsoflocalincapacityarenotasviable.Localexpertsare perfectlycapableofmakingpolicydecisions,yettheir develop-mentisoftenhandicappedbythetendencytorelyoninternational

authoritiesandforeignconsultantsoftenhavelittleunderstanding ofthenationalcontexts.

5.4. Fundingshortfallsandaidvolatility

In terms of the portion of the nation’s economy, Britain’s programmeofassistanceisthreetimesthesizeofthatoftheUS andhalfagainthesizeoftheassistancefromGermany(Economist, The,2012:60).ThetotalofUNESCObudgetofUS$989million5is about one-half the budget of an American research university (Heyneman,2011a). ThoughtheWorldBank allocates20 times thisamounttoeducationprogrammeseachyear,theportion of loansitallocatestoeducationisonly4percent,alevelnohigher than it was 20 years ago. In addition to being insufficient, educationaidvariesinparallelfashionwithdomesticpriorities and military and commercial interests. There are also many examplesofeducationaidbeingdiverted,aswellasinstancesof graftandcorruptionpervadingtheeducationsector.

5.5. Dependency

Insomecountries,educationaidhascreated dependency.In 2008, overall aid was greater than 10 per cent of GDP in 21countriesinsub-SaharanAfricaandexceededdomesticpublic spending in one out of three countries. In terms of education assistance,aidconstituted70percentofthedomesticeducation budget in Gambia,66 per centin Mozambique, 60 percentin Kenya, 55 per cent in Zambia, and 51 per cent in Rwanda (Fredriksen,2011).Thislevelofdependencycreatesproblemsof manykinds,themostimportantofwhichistheimpressionthat nationalsovereigntyhasbeencededtoexternalauthorities. 5.6. Inconsistency

ChinareceivedUS$697millionineducationalaidin2007,while IndiareceivedUS$423million.Yetthesecountrieshavesufficient resources to finance space programmes, nuclear arsenals and militariesofsignificantsize.Thequestioniswhythesecountries cannotfinancetheireducationalrequirementsbyreorderingtheir domesticpriorities6.

5.7. Inter-donorcoordination

Another counterproductiveinfluencehasbeendonor coordi-nation,bywhichdonorscombineprogrammesanddirectthemtoa coordinatedpurpose(Collier,2007:101).Thoughduplicationisa probleminitsownright,excessivedonorcoordinationcanreduce choice and competition, while leaving an aid-receiving nation morevulnerabletomistakesindirectionduetoshort-termfadsin developmentpriorities(Heyneman,2010).Single-issueaid priori-tizationalsoresultsinlittleassistancebeingdirectedtoregions wherethatissueisnottheproblem.Withregardtoeducationaid, wherebasiceducationisnotthemostimportantpriority,suchas EasternandCentral Europe,LatinAmerica andtheMiddleEast, foreignaidtoeducationhasbeenfluctuatingovertime,however,it eventuallydecreasedandnearlydisappeared.

5

AsUNESCOhasabiannualbudget,theannualbudgetforeducationismuch smallerthanthisfigure.UNESCO’seducationbudgetwasonlyUS$54millionineach of2008and2009(17percentoftotalUNESCObudget),ofwhichonlyUS+$16.5 millionwasallocatedforoperationalactivities(Fredriksen,2010).

6Rawls’(1971)secondprincipleofjusticestatesthatpublicbenefitsshouldbe targetedsothatthegreatestbenefitwouldbecapturedbytheleastadvantaged. Assistingacountrywithproblemsofprimaryeducationwhenthesamecountryisa nuclear power suggests that the internal priorities are not sufficiently re-distributivetodeserveassistancefromtheworldcommunity.

6. Theimpactofideologyoneducationaid

Inter-donorcoordinationmayleadtoanunanticipated conse-quence,the dangerof a singleemphasis on basic educationas beingthehighestpriorityforeducationaidprogrammes world-wide.Itmightperhapshelpillustratethenatureoftheproblemby considering another sector as a comparison (Heyneman, 2009, 2010,2012a).

Foreignassistancetothehealthsectorcouldnotbesuccessfulif the only priority considered legitimate was assistance to rural healthclinics.Ruralclinicsfunctionaspartofaninterdependent systemthatincludeshospitals,researchanddevelopment facili-ties,anefficientpharmaceuticalindustryandnetworkstocarefor specific significant diseases, such as HIV/AIDS or malaria. Developing a sustainable system of specialized training and expertiseinhealtheconomics,epidemiologyandhealthstatistics is as necessary as rural health clinics. The same diversity of componentsthatmakes forsuccessfulforeignassistance tothe health sector is also applicable to aid for the environment, agriculture,transportandpublicadministration.

What pertains in these sectors is also true of education. However, since the 1990s, the donor community has become precoccupied by with basic education and education-for-all (Fig.2),aninternationalstatementofintentsignedin1990 com-mittingsignatorycountriestoensurethatallchildrenareenrolled inschoolwithanadequatequalitybyacertaindate.Thatdatehas arrived,andtheresultshavenotbeenuptotheoriginalaspirations (UNESCO,2007).

Thereiscertainlyaneedforbasiceducation,andeducationaid shouldnotneglectit.Butwhatbeganascommonsensehasturned intoanideologyinwhichothereducationsubsectorsweretreated asheresy.Agenciesthatexpressthedesiretoassistsecondaryor higher education, research or statistics, medical education or engineering,arenowtreatedashavingadisregardnotonlyforthe world’spoorbutalsoforrationaleconomicpolicy.

Thiscould have been offset if otheragencies had exercised intellectualleadership.Buttheydidnot.Theresultingconformist behaviourisonereasonwhythelevelofeducationalassistanceasa portionofoverallaidhasstagnated(Table1),andwhyassistance tohighereducation,wheretherearenaturalfiscaleconomiesof scale, hasslipped toonly 6 per centof World Bank education lendingin2010.Italsoexplainswhyorganizationswithinterests insubsectorsotherthanbasiceducation,suchasuniversitiesand vocationalassociations,havelostinterestindevelopment.

Theeffectofthishasbeendisruptivetotheefforttoachievea consensusregarding therole ofeducationinnationaleconomic development.Ithastothecontrarysplinteredtheeducationaid

communityintowarringcamps,somearguingforbasiceducation as if it were a holy war, while others criticizing international agenciessuchastheWorldBankforprovidingfalseevidenceto justify its view. UNESCO, UNICEF and the major national aid agenciesareequallyresponsible.Theinternationalcommunityhad already allowed theeducation statisticsfunction of theUnited Nations toallbut disappearinthe1990s, makingitdifficultto monitor progresswithcomparable statistical standardsused in other sectors. No agency has been sufficiently courageous to deviate fromtheaccepted education-for-allmessage. Nonehas taken the lead in demanding that education policy be more balanced.Someagencies,suchasUNESCOandtheInternational InstituteofEducationPlanning,havebeensofocusedontheleast developedcountriesthattheyhavevirtuallyrecusedthemselves frommakingacontributiontoeducationdevelopmentanywhere else.

The absenceof professional leadershipin education aidhas resultedinthedevelopmentcommunity shiftingitsenergy and attentiontootherpriorities,notablyhumanrights,the environ-mentandgoodgovernance.Theabsenceofa balanced develop-mentstrategyfortheeducationsectorhasalsomeantthatprivate organizations, includingmajorassociationsofuniversities, tech-nicalinstitutesandprivatebusinesses,havetakenonlyamarginal interest in development on the groundsthat the development communityhadlittleinterest––orinthecaseofprivatebusiness,a hostility-towardswhattheycouldoffer.

7. Usingaspirationaltargetstoplandevelopment

From the first meetings in Thailand objectives in 1990, objectivesofEducation-for-Allhavebeenestablishedbycountry representatives together and setting targets. In 2000 these included theMillennium DevelopmentGoals and in 2015they willincludetheSustainableDevelopmentGoals.Theagreements, ineffect,arestatementsofaspirations.Theyhavenobasisinlaw. Nosanctionsareassociatedwiththefailuretoattaintheintended targets.Thepromisetoallocateresourcesisimbalancedbecause theyfallspecificallyondonorsbutnotrecipients.Theinterestof therecipientstherefore maybetoincrease thelevelsof donor commitmentby increasing thebreadthand theseverityof the targets.Thegoaloffullschoolenrolmentin1990wasexpandedin 2000toincludeeightgoalsincludingloweringratesofpovertyand hunger. TheSustainable DevelopmentGoals have notyet been decided but original proposals included 17 of them, first with 212andthenwith169targets.Theseincludegoalspertainingto urbanization, infrastructure, standards of governance, income inequalityandclimatechange.Thishasraisedmanyconcerns.

Onesetofconcernssuggeststhatthemorethegoalstheless likelytheyaretobetreatedseriously.Asecondisthatsomein educationareun-measurable.Goal4.7forinstanceproposes:

By2030ensurealllearnersacquireknowledgeandskillsneeded topromotesustainabledevelopment, includingamongothers througheducationforsustainabledevelopmentandsustainable lifestyles,humanrights,genderequality,promotionofaculture ofpeaceandnon-violence,globalcitizenship,andappreciation ofculturaldiversityandofculture’scontributiontosustainable development’’(Economist,The,March28th2015).

It is thecase that the goalset in 2000for thereduction of povertywasindeedmetby2010.In1990about43%oftheworld’s populationlivedinpoverty.Thiswasreducedto33%in2000andto 21%in2010(Economist,The,June1,2013).Butisitthecasethat settingagoalandincreasedallocationsofinternationalaidwas responsibleforreducing poverty?Reductionsin povertywithin Chinaduringthisperiodaccountedfor75%oftheworld’spoverty reductionandalthoughChinaisarecipientofforeignaid,including IDA,this hadlittletodowiththereductionofChinesepoverty. Chinese poverty was reduced through economic growth and economicgrowthwaslargelyattributabletointernationaltrade.In terms of the world at large, for every dollar spent on trade liberalization resulted in $US 2,011 dollars in benefits in developmenttargets.Foreverydollarspentonprovidinggreater preschooleducationresultedin $32inbenefitsin development targets((Economist,The,January24,2015).Thisisnottosuggest thatpreschooleducationprogramsareunworthyofinvestment;it is to suggest that many of the goals can be attained through mechanismsotherthanforeignaid.

Intheeyesofsome,foreignaidisanindustry,avestedinterest withitsown senseof priorities governed by thestatus quo in whichtheinterestsofexpertsarealignedwiththoseofdictators (Easterly,2014a,b).Theargumentisthatplanningbyexpertssuch asintheuseoftheSustainableDevelopmentGoalsis basedon patronization of developing countries. The goals call for more resourcestobemadeavailablefromwealthypartsoftheworldand sent tocountries where theymay be subjectto systematically stolenbythoseinpower.Theexpertssupportingthisindustryare well compensated and moreover have the self satisfaction of performinganactofcharity.Thisindustry,itisheld,isselfserving. Itdoesnotrequirebudgetaryreallocationsindevelopingcountries oranytangiblesacrifices.Theeffectisthatdevelopingcountries canactasnegotiatorsforbenefitssomeoneelseissupplying.The resultinsomewaysisthat

each countryand aidlobbyist hasa target forits particular bugbearandisnowunwillingtogiveitupunlessothersgiveup theirs. Something for everyonehas produced too much for anyone. Making matters worse, some developing countries think eachextragoalwillcomewitha potofmoney,sothe moregoals,themoreaid(Economist,The,March28,2015). 8. Options

8.1. Endingforeignaid

Some critics have argued for eliminating development aid (Moyo,2009;Easterly,2014a,b;Ramalingam,2014).Somesuggest thatitismorelikelytoobstructdevelopment(Bauer,1972);orthat itisawasteofresources(Dichter,2003);thatithasnomeasurable effectoneconomicgrowth(RajanandSubramanian,2005);that helpssupportbadgovernmentsandenrichelites(Easterly,2006). Bauer (1972) suggests that aid creates dependency, fosters corruptionandexacerbatesimperfectionsinlocalmarkets.Moyo (2009)suggests that aidcan increase thechances of domestic

conflict and add to inflationary pressures. Although some successful aid programs are acknowledged, the critics suggest thataidshouldbereplacedbyinternationaltrade(Bauer,1972; Dichter,2003;Easterly,2006;Moyo,2009).

Althoughsomefindingssupporttheargumentthataidhasno effectonnationalgrowth,BurnsideandDollar(1997)’sfindthat aidwas effective in countries withsound economic and social policies.Nevertheless,theirfindingswerechallengedbyDalgaard and Hansen (2001) who suggest that the Burnside and Dollar (1997)resultswereaffectedbychangestotheirsamples.

Most studies look at the effects of aid on macro-economic growth.Butaidmayaffectotherspecificelements,suchasschool enrolment. The studies discussed in Section 4 shows that educationaidhadmoderatelypositiveeffectonschoolenrolment. Asmentionedabove,eventhemostseverecriticsacknowledge aidsuccesses,andmanyofthosehavebeenintheeducationsector. Dichter(2003)andEasterly(2006)notedthataccesstoprimary educationhashelpedtochangetherateoffemaletomaleliteracy rateoverthepastthirtyyears.Inthe1990s,forthefirsttime,there wasadeclineinthefertilityrateofthedevelopingcountrieswhich is associated with greater access to schooling (Dichter, 2003). Easterly (2006) acknowledges some successful cash transfer programstoenrolstudentsinschoolsinBangladeshandKenya. Whilemuchofthesuccessofeducationaidhasbeenonincreasing theenrolmentinschools,theaideffectivenessonthequalityof learningstillremainsquestionable(Riddell,2012).

8.2. Improvingeducationaid

Donoreffortstoconfronttheproblemsofaidhaveresultedinan importantseriesofrecommendationsforimprovementinthe ‘post-2015era’.Whileallocationstoeducationwithintheaidportfolio declinedbysevenpercentbetween2010and2011(UNESCO,2013), thenewEFAgoalscallforaidtoincludespecifictargetsforeach donorofaboutonepercentofGDP(UNU-WIDER,2014).

Somehavecalledforhumanitarianaidtocontinuespecifically for the social sectors—health, water, sanitation, education and social protection, in parton the evidence of recent enrolment increasesinSub-SaharanAfricafrom57to78%forboysandfrom 50to74%forgirlsinjust20years(UNU-WIDER,2014).Othershave suggested that aid be improved by learning from ‘complex adaptive systems’,essentiallytheprocessof learning frompast mistakes(Ramalingam,2014).Somehavesuggestedthatthenext been challenge is not enrolment but learning and in fact that Millennium Development Goals might be replaced by the Millennium Learning Goals (Barrett, 2011). New criteria for education development have been suggested by Unterhalter (2013)andbytheBrookings/UNESCOLearningMetricsTaskForce (Brookings,2013).ParallelwiththenewWorldBankEducation Policy Paper (World Bank, 2012), the taskforce calls for new, quickly administered, criterion-reference achievement tests throughoutdevelopingcountriesandnewindicatorsofprogress. These might include: (i) measures of completion, reading comprehension atthe end of primary school,(ii) betteruse of netenrolmentrates;(iii)testsofreadingandnumeracy,(iv)early childhooddevelopment,(v)citizenshipvaluesand(vi)exposureto learningopportunitiesacrosssevendifferentdomains(Brookings, 2013).Althoughthetestingforlearningqualityandmoreaccurate measurements of attainment have been long overdue, doubts remainastothelogisticalimplicationsandpotentialsideeffectsof globaltesting(Barrett,2011;HeynemanandLee,2012).Itremains ananomalytoothat theUnitedStates,beinga largesources of demandforbettereducationalstatistics,iscurrentlynotevena memberofUNESCO,theUnitedNationsorganizationchargedwith the responsibility for improving education statistics, hence the scepticismovertherealismofthecallsforglobaltesting.

Themodalityofassistanceshiftedovertimefrombeingproject specifictobeingpolicybased.Theformerwasjudgedtobeslow andoverlydirectiveinthesensethatittendedtomicro-manage theimplementationofprojects.Butbasingassistanceonchanges insector-widepolicieshasnotsolvedpastproblemsandhasraised new and unintended concerns. Policy-based assistance has developeda reputationfor beinginvasivein thesensethat the conditionsare oftenset by a processcharacterized by unequal accesstoinformationandmethodsofanalysisbetweenlenderand recipient.Moreover policy-basedaidhasincreasedthescaleby whichresourcescanbedivertedawayfromintendedgoals.Lastly, policy-basedaidhasnotaugmentedthecourageofdevelopment assistanceagenciestoceaseassistancewhenproblemsor short-fallsinobjectiveshavebeenencountered.Whatshiftedwasthe magnitudeoftheassistanceandthedegreetowhichborrowers couldbeheldaccountableexpostfacto.

Among the more important innovations in designing aid programshasbeencharacterizedas

Cash on Delivery or Results-Based-Aid (RBA). The idea is relativelysimple.Ifarecipientcountrywantstoreachtheobjective it should be willing to reallocate its own resources to make progressreachingit.Thisisatestofpoliticalwill,theingredient judgedtobemissinginmanyprogramsofpastassistance.Italso breakstheinterdependencebetween‘expertsandthedictators’in that the mechanisms of what works is relatively unimportant. Policyborrowingthroughconditionalitycanbereplacedbysimply notingtheimprovementsinthetargetobjectiveandtheallocation ofassistanceexpostfacto.Somesuggestthat thismightfreeup accountantsandmanagerswhomightbebetteremployedrunning public services (Economist, The, May 23, 2015). Though such programs have only recently been designed, early results are encouraginginthecaseofprotectingtropicalforests(Seymourand Busch,2014),finance(DevelopmentImpactWorkingGroup,2013) and Energy (Savedoff, 2015). In one review of the literature, authorshavepointedoutthattraditionalaidwithitsemphasison howpaymentsareusedmaybeacaseof‘doubledemanding’in thataccountingisrequiredforbothinputsandoutputs.(Perakis andSavedoff,2015).Whatmotivatescountriestoachievebetter performancewithResults-Based-Aid(RBA)?Somesuggestthatit may be attributable to four possible motives: (i) pecuniary interests(countriesneedthemoney),(ii)attentionfocus(because theconnectionbetweenfundsandresultsissoclearpoliticiansand administratorscanmoreeasilyfocusonthem),(iii)accountability (RBAaremoretransparenttothepublicwhichthereforeallows themtomoreeasilyholdtheirgovernmentsaccountable,and(iv) recipientdiscretion(theabilityoftherecipienttochooseamong mechanismsofimplementationwhichisclosertolocalknowledge, capacity and innovation) (Perakis and Savedoff, 2015). One exampleofRBAintheeducationsectorisaprogramtoaugment secondary school enrolment and examination performance in EthiopiasponsoredbyDFID.$US157waspaidtoEthiopiaforeach additionalpupilsittingfortheschool-leaving examination;and $US157foreachadditionalpupilwhopassed.Twoyearsafterthe program began 45,000additionalpupils tookthe examand an additional42,000passedtheexamination(EconomistThe,2015). TheresultsaretoorecentandsmallscaletoconcludethatRBA isaviableoptiontothetraditionalmeansofdistributingaid.Most RBAprogramshavebeendirectedtobusinesses,NGO’shouseholds and communities; only a few so far have been directed to governments.Ofthesixgovernment-directedprogramsanalyzed eachachieved‘somesuccess’.DeforestationhasdeclinedinBrazil, more Ethiopian children are completing secondary school and morechildreninCentralAmericahavebeenimmunized.However theprogramspromisedtoolittlemoneytomotivategovernments forpecuniaryreasons,didnothavethetransparencytomotivate for constituent accountability reasons, continued to involve

funders in program design to test the motivation of recipient discretion.Itisspeculatedthatthemotivationhingedontheclarity andsimplicityoftheresultssuggestingthatincreasedattention tooutcomesamongstaffofbothfundingimplementingagencies hasbeenthekeymotivationthusfar.

Theeducationsectortodayconstitutesalargeenterprise,which includes programmes (curricula which lead to a degree or certificate), products (books, computer software) and services (testing,testpreparation,consulting).Combined theyconstitute thesixthlargestserviceexportoftheUSandatopicofsignificant concernfordiscussionwithintheWTO(Heyneman,1997,2001). Schoolsaretheworld’slargestsourceofemploymentandalarge source of demand for computer software, furniture, chemicals, booksandelectronicequipment(Heyneman,2001).Educationaid hasnottakensufficientaccountofthemagnitudeofthesector’s commercialvibrancy(Heyneman,2011b).

Becauseforeignaidhasapoorreputationpolitically,suggestions onhowtoimproveitmustbeplacedincontextofpoliticalrealism. Forexample,byonereport,thedesireofthe Americanpublicto reduceforeignaidrankedgreaterthantheirconcernovernuclear war(Moyo,2009:74).AbouthalfoftheBritishpublicbelievethat ‘Britainshouldlookafteritselfandleavepoorercountriestosort themselvesout’(Economist,The,2012:60).Thereputationofaid generallymirrorsthatofinternationalorganizations.Thoseagencies responsible for education issues have been slow to seek a diversificationinresourcesandhencearelesssustainable (Heyne-man,2011a)Theyhaveneglectedareasoftheirresponsibilitywhich OECD countries need themfor most (Heyneman, 2003a,b), and insteadoffacingfulfillingtheirmandateofaddingtotheworld’s knowledgeofeducation,theyhaveconcentratedoneducationinthe world’smostvulnerablecountrieswhichareleastlikelytobecritical oftheiradviceortheprofessionalismoftheiranalyses(Heyneman andPelczar,2005).

On the other hand, the world cannot simply ignore the education needs of the most vulnerable. If there is justice in financingtheeducationalopportunityofone’sneighbour,thereis justification for considering any deserving family to be one’s neighbour (Heyneman, 2003c, 2006b). The problem is that programmeswhich limitaidtoareasor countriesin whichaid willbeeffectiveleavesoutmostoftheworld’spoor(Heyneman, 2003c, 2004a), and private philanthropy does not constitute sufficient resources to make up for the scarcity of public philanthropy(Heyneman,2005).

Butthereareanumberofwaysinwhicheducationaidmightbe improved.Theyincludebetterstrategy,betterinnovation,andmore courageousadmissionofsensitivebutnecessaryissues.Theybegin with broadening the scopeof educationaid beyondthe current fixationonbasiceducation.Developmentassistanceagenciesneed totakealeadershippositionwithrespecttoarticulatingadiversity ofeducationalpriorities.Bilateralagenciesshouldpioneerareasin whichtheircountriesexcelandhaveacomparativeadvantage,such astechnology,highereducation,vocationaleducationandprivate education7.Agencieswithspecificeducationalmandates,suchas UNESCO, need to reiterate the interdependence of education subsectors, bothpublicandprivate,andthe importanceofallof them.Theyshouldalsoattempttoliveuptotheirrealmandateand speaktoeducationproblemsandchallengesworldwide,includingin the US,Europeandthe industrialdemocracies.By limitingtheir attentiontodevelopingcountries,theyfailtoliveuptotheirtrue purpose:tospeakforeducationglobally.Finally,thenextfrontierfor educationassistancewillbetoassistcountriesinthinkingthrough thecomplexitiesofestablishingworld-classuniversities.Thisisan

7

This policymaybe inconsistentwith thatof Britainwhose development assistanceagency(DFID)isrestrictedfromtakingBritishcommercialinterestsinto account.

areaofhighdemand,butwhichdevelopmentassistancehasyetto explore.

Developmentassistanceagencieshavebeenremissintermsof gatheringthenecessarydatatomonitorandevaluatethechanges ineducationpolicy.Thisinadequacyhasbeendue,inpart,tothe tendency of development assistance agencies to finance the evaluationeffortsoutofprojectfunds.Thisiscommonlyresisted byrecipientcountries,perhapsonthegroundsthataidfordataand researchislowerinprioritythanaidformoretangibleproducts and services. However, the new Education Sector Policy paper publishedbytheWorldBank(2012)isastepinanewdirection.It callsforasetofgrantstooffsetthecostsofcollectingregulardata on education operations whether financed from domestic or internationalsources.

Perhapslendingtotheprivatesector(suchasthroughtheIFC) andspecialistseducationventurecapitalmightplayanimportant role.LearnCapital(leancapital.com),RethinkEducation (rteduca-tion.com)and New Schools Venture Fund (newschools.org)are illustrations.Theirfocusisonthedevelopmentofprivateproviders ofeducationalgoodsandservices(training,testing,textbooksand otherequipment,educationsoftwareandafterschoolpedagogies, etc.).Theyaugmenttheprofitsoflocaleducationcompanies.They assistinthedeliveryofbettereducation,andtheyatthesametime, theyavoidthetypicalrelationshipsgeneratedbycharities.

In highaid-impact countries suchasGambia, where foreign assistance accountsfor 70 per cent of thepublic spending on education, or in conflict countries such as Liberia, foreign aid shouldbetakenasanindicatorthat thecountryhasalready in essencelost itssovereignty over theeducationsector.In these cases,a trusteeshipcouncil couldmanage theeducationsector untilsuchtime asdomesticinstitutionsaresufficientlycapable andsustainabletobeeffective.Intechnicallycompetent,yetpoor countries with significant military expenditures, educational assistanceshouldbereviewed.This is,for instance,partof the justificationusedbytheUKtoceaseassistancetoIndia8.

The most recent education policy paper of the World Bank recommendsaworldwidepriorityongatheringdatatomonitor andevaluateeducationalprogress(WorldBank,2011).Thisseems sensible.ThemonopolisticpositionoftheWorldBankwhichhas theresourcestoprovidethelion’sshareoftheanalysesonwhich projectsare based,andthelion’sshare oftheresourcesfor the projectsthemselves,shouldbebroken.Thenumberandmandates ofthemultilateraldevelopmentagenciesshouldalsobe rational-ized. Overlapping authority should be reduced, while basic functionsonwhichalldepend,suchasstatistics,evaluationand research,shouldbecoordinatedacrossinstitutions.

This could be done in three ways. One is to follow the recommendationsoftheMeltzerCommission(2000).Theirreport recommendedthat theWorldBank beresponsiblefor analysing developmentproblemsandmakingrecommendationsbutthatthe projectsthemselves should beidentified,managedand financed through the regional development banks and the new Asian InfrstructureInvestmentBank(AIIB).Inessencethiswouldde-link theanalyticworkfromthelendingprogrammeandthusallowa naturalset ofchecksandbalancestooccurwithinthe countries themselves.

Anotheroptionwouldbetoplacetheanalyticcapacitywithin thecountriesthemselvesbyhavingthemdecidewhattoanalyse andwhoshouldperformtheanalyses.Thisappliestoalllending, notonlytolendingforeducation.TheAsianDevelopmentBankfor instance,makesgrantsforthetechnicalassistancethatunderpins lending9.TheWorldBankmightgrantmoniesforanalyticworkin

thesameway.Countrieswouldrequestproposalsjustastheydo forotherkindsoftechnicalassistance.Bidswouldemergefrom universities, private companies, foundations and perhaps other publicauthorities,bothlocalandinternational.

Itmightbeusefultoconsiderawaytodeveloppolicies,which underpin education lending by diversifying it within the UN system. Were the policyanalytic capacity augmented (Mundy, 1998,1999,2002,2002/2003)UNESCOmightberesponsiblefor theeducationpoliciesonwhichWorldBanklendingcouldthenbe established.Thisoptionwouldavoidtheproblemsofthecurrent monopolyofbothanalyticandlendingauthoritynowenjoyedby theWorldBank.Thiswouldplaceprofessionalresponsibilityfor educationpolicywithintheinstitutionwhosetermsofreference coverthefullgamutoftheeducationsector,notjusttheactivities relatedtointernalandexternalefficiency10.Althoughefficiencyis anessentialelementina country’seducationpolicy,policieson efficiency alone cannot cover the full range of professional responsibilitieswhichconstituteanormalpartoftheeducation sector.Thismayalsopertaintothehealthandagriculturesectors where UN agencies compete with the World Bank for setting policy.

Policiesforrationalizingthefunctionsofbilateralagenciesare constitutionallydifferent.Theyremaintheprerogativeof autono-mousdomesticgovernments.Thegreaterthediversityofbilateral participation–withnewagenciesintheRussianFederation,Brazil, ChinaandKorea–themoreautonomoustheirpolicymakingcanbe expectedtoremain.However,allbilateralagenciesareopen to consensus-buildingandtocollaborationwhenthegoalsoverlap. 9. Conclusion

Thepotentialofeducationaidremainssignificantovertime.It is less controversial than many sectors – industry, tourism, agriculture,banking–wheretheseparationbetweenprivateand governmentresponsibilitiesislessclear.Researchresultsonthe importanceofhumancapitalinvestments,thoughchallengeand perhapsnon-linear,remainsignificantandconstant.Investments in education continue to elicit significant monetary and non-monetary rewards both for the individual and for the wider community.Theindividualbenefitsfromcomparativeadvantages in the labour market, in adaptability in times of economic transition and in spin-offs in terms of household efficiencies, beneficial health practices and inter-generation savings. The communitybenefitsfromgreaterproductivity,increasedpolitical participationandsocialcohesion.

However, the problems of education aid are non-trivial. In general they parallel problems of development aid generally. Corruption, overdependence on aid, lack of institution-building andfaddishideologiesareknowninothersectorsaswell.TheRBA approach has significant potential to replace the traditional project-basedassistance.Reconstructionaid,however,shouldbe considered separate from development aid. Reforming and rationalizingtheinternationaldevelopmentassistance organiza-tions is likely to be an inevitable consequence of the post 2015agenda.

The key to appreciating the past half-century of education assistanceisperhapstoacknowledgethatwhatcommencedasa novelideaistodaytakentobethenorm:humancapital,inthe formofeducatedpopulations,isasinequanonofdevelopment. Basiceducationhasbecomelargelyuniversal,whilegenderequity in education access is close to being realized. Furthermore,

8

Highlightingthesensitivityofthedonor/recipientrelationship,thepresidentof IndiadescribedBritain’sassistanceprogrammeas‘apeanut’(Economist,2012.60).

9

Thequalityoftheanalysesisnotguaranteedhowever.

10

Thecounter-argumenttothisoptionisthefactthatmemberstatesofUNESCO arerepresentedbytheministersofeducationwhereasthememberstatesofthe WorldBankarerepresentedbythefinanceministers.Ministersofeducationhave noauthoritytodecidepoliciesofinter-sectorresourceallocation.

attention has shifted from providing access to education to providingqualityofeducation.Policymakersnowmustturntheir sights on what the next half-century of education aid can realisticallyaccomplishinanimperfectinstitutionalenvironment in which there are significant and legitimate demands for the allocationofscarceresourcestowardsdomesticneeds.Inaddition itisreasonabletoexpectcommitmenttowardsthereallocationof localpriorities.Theeraofnewlyindependentnationsisover;what liesaheadofusisanewerainwhichallnationswillhavesimilar

expectationsformaintainingthehealthandeducationoftheirown populations.

Acknowledgements

ThisarticlewaspreparedundertherequestofUnitedNations University’sWorldInstituteforDevelopmentEconomicsResearch (UNU-WIDER). We thank Miguel Nino-Zarazua for his helpful commentsonthisarticle.

AppendixA. Appendices A.1. A.Listofacronyms

AU AfricanUnion

AusAid AustralianAgencyforInternationalDevelopment CIDA CanadianInternationalDevelopmentAgency DFID DepartmentforInternationalDevelopment ECA EuropeandCentralAsia

ETS educationtestingservice

EU EuropeanUnion

EUROSTAT StatisticalOfficeoftheEuropeanUnion FAO FoodandAgriculturalOrganization GDP grossdomesticproduct

IBRD InternationalBankforReconstructionandDevelopment IDA InternationalDevelopmentAgency

IEA InternationalAssociationfortheEvaluationofEducationAchievement ILO InternationalLabourOrganization

IMF InternationalMonetaryFund

JICA JapanInternationalCooperationAgency KOICA KoreaInternationalCooperationAgency LAC LatinAmericaandtheCaribbean NAFTA NorthAmericanFreeTradeAgreement NCES NationalCentreforEducationStatistics NGO non-governmentorganization

OECD OrganizationforEconomicCooperationandDevelopment SEAMEO SoutheastAsiaMinistersofEducationOrganization SIDA SwedishInternationalDevelopmentCooperationAgency SSA sub-SaharanAfrica

UIS UNESCOInstituteofStatistics

UNESCO UnitedNationsEducation,Scientific,andCulturalOrganization UNICEF UnitedNationsInternationalChildren’sFund

USAID UnitedStatesAgencyforInternationalDevelopment

WB WorldBankGroup

WTO WorldTradeOrganization

A.2. B.Listofbasicfactsoneducationalaidofthemultilateral,regionalandbilateralorganizations Name Majorprioritiesintheeducationsector Datewhenit

began Monetarycommitment ineducationinrecent fiscalyr(US$) %ofoverall activitieson education Source Multilateraland regionalorganizations UNESCO Educationforall,qualityandinclusive

education,educationforsustainable development

1945 169,484,500* 26 36C/5Approved

Programmeand budget(2012–2013) UNICEF Basiceducationandgenderequality 1946 709,000,000**

20 AnnualReport2011 WorldBank Basiceducation,highereducation,

vocational,in-servicetraining,pre-school

1944 1733,000,000 4 AnnualReport2011

ILO Skillsandknowledgeforyouth employment,competitiveness,growth

1919 93,500,000 9 Programmeand

budgetforthe biennium2012– 2013

AppendixA(Continued)

Name Majorprioritiesintheeducationsector Datewhenit began Monetarycommitment ineducationinrecent fiscalyr(US$) %ofoverall activitieson education Source Bilateral organizations JICA(Japan) Basiceducation,technicalandvocational

education,highereducation

1954 185,333,200 14.20 AnnualReport2011

USAID Improvingearlygradereading,accessto highereducation,educationforyouthin crisisandconflictsituations

1961 1348,000,000 2.80 Departmentof State-USAIDJoint summaryof performanceand financialinformation fiscalyear2010 DFID(UK) Accesstoprimaryschoolandlower

secondaryschool,completingprimary education

1961 960,053,625 14.50 DFIDAnnualReport

andAccounts2011– 2012

CIDA(Canada) Primaryeducation,educationpolicyand administrativemanagement,education facilities,teachertraining,vocational training,highereducation

1968 418,290,000 11.60 Departmental PerformanceReport 2010–2011/ StatisticalReporton international assistance2010– 2011

SIDA(Sweden) Primaryeducation,educationpolicyand administration,vocationaleducation, highereducation

1965 139,000,000 4 AnnualReport2011

KOICA(SouthKorea) Expandingopportunitiesforbasic education,vocationaleducation, improvingenvironmentforhigher education

1991 100,128,000 24.50 KOICAAidStatistics

2011

NORDAD(Norway) Basiceducation(thelargestportion), post-secondaryeducation,secondaryeducation

1960 255,343,467 5 Norwegian

DevelopmentAid 2011bysector AusAID(Australia) Developmentscholarships(39of

educationbudget),basiceducation(28), educationgovernanceandsector-wide activities,technicalvocationaleducation, secondaryeducation,highereducation

1974 NA 17 AusAIDAnnual

Report2010-11

B:Listofbasicfactsoneducationalaidofthemultilateral,regionalandbilateralorganizations Name Majorprioritiesintheeducationsector Datewhen

itbegan Monetarycommitment ineducationinrecent fiscalyr(US$) %ofoverall activitieson education Source

Netherlands Basiceducation,vocationaleducation, disadvantagedgroups

1965 471,319,000 7.7 OECDDAC

2010Creditor ReportingSystem TheBelgianDevelopment

Cooperation

Highereducation,vocationaland technicaleducation,primaryeducation through‘globalpartnershipfor education’(fasttrackinitiative)

1985 136,000,000 10.0 AnnualReport

2011

AustrianDevelopment Agency

Vocationaltrainingandhigher education

2004 11,590,000 10.43 AnnualReport

2009 FINIDA(Finland) Nopriorityineducationin

developmentprogrammes,primary education,qualityeducation

NA NA AnnualReport

2011 FrenchDevelopment

Agency(France)

Basiceducation,vocationaltraining, highereducation

136,284,000*** 1.6* AnnualReport

2011 Germany Primaryeducation,technicaland

vocationaleducation,highereducation

1,731,630,000 15 OECDCRS

Luxemburg Vocationaltrainingandaccessto employment,basiceducationand literacy

1978 26,123,674.96 28.65 Luxembourg

Development AgencyLeaflet, 2010 NZAID(NewZealand) Teachertraining,vocationaleducation,

highereducation

2002 146,500,000 25 2010/11Yearin

Review

Spain Basiceducationandtraining 1988 NA NA

SwissAgencyfor Developmentand Cooperation

Basiceducation,vocationalskillsand development

1944 37,966,000 1.98 OECDCRS

IrishAid(Ireland) Universalprimaryeducation,public educationsystems,equalityin education

1974 52,476,720 9.4 AnnualReport

2011

Theyearwhenbilateralaidbeganandtheestablishmentofbilateralagencycanbedifferent.Officialwebsitestendtoshowtheestablishmentoftheirorganization.Thus,the ‘datewhenitbegan’canbelaterthantheactualyearwhenbilateralaidbegan.Source:Compiledbyauthors.*

UNESCOhasabiannualbudget,thustheannualbudgetfor educationissmallerthanthefigure.**

UNICEFfigureiscategorizedas‘basiceducation andgenderequality’andincludesregular(4%) andextrabudgetary(17%) expenditures.***

Frenchagencydoesnotreporttheamountandportionallocatedtoeducation.Theamountandproportioniscalculatedbyauthorsbasedonthelistof educationprojectsintheannualreport.