SEXUAL PARTNER TYPE AND RISK OF INCIDENT HIV INFECTION AMONG ADOLESCENT GIRLS AND YOUNG WOMEN IN RURAL SOUTH AFRICA

Full text

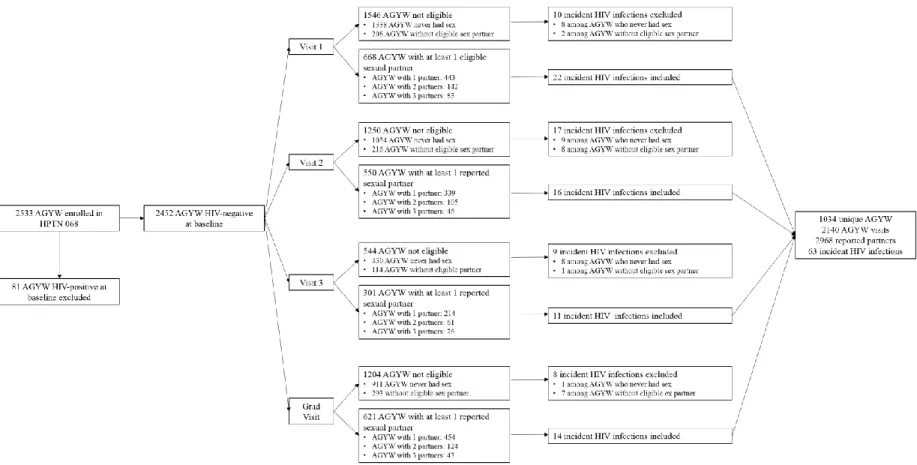

Figure

Related documents

The expressing power of the whole public expenditures on the housing and the community amenities in individual countries of the EU in connection with the housing quality problems

Space through space, What you hear is not a test / Lou Masduraud & Antoine Bellini... Space that will not

Appendix A: 10m x 10m snail plot setup and search 163 Appendix B: Estimating the proportion of snails not observed 166 Appendix C: Habitat descriptions of the Powelliphanta augusta

By this concept two parametric nonlinear programming problems are defined; one with parameters in the objective function and the other with parameters in the constraints, the

Working adolescent girls were at nearly twice the risk ( p =0.009, odds ratio=1.8) of having low serum ferritin and low serum folic acid concentrations ( p =0.006, odds ratio=1.9)

BTB extract induced morphological changes in breast cancer cell lines, including cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, and cell rounding, versus untreated cells under phase-contrast

What makes deeper this issue is the fact that they have researched to find differences and similarities between same types of alternative measures provided by different penal codes

These compounds react with metallic surfaces, at prevailing high temperatures, to form metallic chlorides, sulphide or phosphides. These metallic compounds possess