RESEARCH ARTICLE TECHNIQUES AND RESOURCES

Second-generation Notch1 activity-trap mouse line (N1IP::Cre

HI

)

provides a more comprehensive map of cells experiencing Notch1

activity

Zhenyi Liu1,2, Eric Brunskill3, Scott Boyle2, Shuang Chen2,3, Mustafa Turkoz2,3, Yuxuan Guo2,4, Rachel Grant2 and Raphael Kopan2,3,*

ABSTRACT

We have previously described the creation and analysis of a Notch1 activity-trap mouse line, Notch1 intramembrane proteolysis-Cre6MT or N1IP::CreLO, that marked cells experiencing relatively high levels of

Notch1 activation. Here, we report and characterize a second line with improved sensitivity (N1IP::CreHI) to mark cells experiencing lower levels

of Notch1 activation. This improvement was achieved by increasing transcript stability and by restoring the native carboxy terminus of Cre, resulting in a five- to tenfold increase in Cre activity. The magnitude of this effect probably impacts Cre activity in strains with carboxy-terminal Ert2 fusion. These two trap lines and the related line N1IP::CreERT2form a complementary mapping tool kit to identify changes in Notch1 activation patterns in vivo as the consequence of genetic or pharmaceutical intervention, and illustrate the variation in Notch1 signal strength from one tissue to the next and across developmental time.

KEY WORDS: Activity, Cre, Neuron, Notch1, Kidney

INTRODUCTION

The Notch signaling pathway is an evolutionarily conserved, short-range communication mechanism utilized throughout life in all metazoan species (Artavanis-Tsakonas et al., 1999). The binding of a ligand to a Notch receptor triggers the unfolding of a juxtamembrane negative regulatory region (NRR), which exposes it to cleavage by the ADAM10 protease (a disintegrin and metalloprotease) at an extracellular sequence termed S2 (Groot et al., 2013; Mumm et al., 2000; van Tetering et al., 2009). S2 cleavage leads to the shedding of the extracellular domain and allowsγ-secretase to cleave Notch within its transmembrane domain at S3, releasing the intracellular domain of Notch (NICD) from the membrane. Three nuclear localization signals within NICD provide for nuclear translocation, where it complexes with RBPjk, recruits the MAML adaptor and the transcriptional activator p300 (Ep300 – Mouse Genome Informatics) to the promoters of target genes (Kopan and Ilagan, 2009).

Whereas only one receptor (Notch) and two ligands (Delta and Serrate) are present inDrosophila, mammals have four receptor paralogs (Notch1-4) and at least five canonical ligands (Dll1, Dll3, Dll4, Jag1 and Jag2). These receptors and ligands exhibit complex expression patterns and play essential roles both during development and in the maintenance of adult tissue homeostasis,

which is evident from various Notch-related congenital diseases and tumors in human patients (Koch and Radtke, 2010; Penton et al., 2012) and in mice lacking Notch receptors or ligands in various tissues (Conlon et al., 1995; Demehri et al., 2008; Gale et al., 2004; Hamada et al., 1999).

Several methods have been developed and used to report Notch activity, each with specific strengths and weaknesses [reviewed by Ilagan et al. (2011)]. Taking advantage of the fact that the intracellular domain of Notch (NICD) requires ligand-induced proteolysis to be released from the cell membrane, we have previously described the creation and analysis of a Notch1 activity-trap mouse line, Notch intramembrane proteolysis-Cre or N1IP::Cre (Vooijs et al., 2007) (Fig. 1A,E). In this knock-in line, the coding sequence for phage recombinase Cre, which was followed by six myc tags (6MT) and preceded by a nuclear localization signal (NLS), was targeted into one Notch1 allele within exon 28, encoding the transmembrane domain of Notch1 (Fig. 1E). This targeting strategy resulted in the expression of a Notch1-NLSCre6MT fusion protein from this locus, in which the intracellular domain of Notch1 is completely replaced by NLSCre6MT. The binding of the ligand to cells expressing Notch1 and Notch1-NLSCre6MT fusion protein triggers the release of NICD and the NLSCre6MT protein, respectively. Whereas the NICD permits normal development, NLSCre6MT, once inside the nucleus, could catalyze the removal of any floxed allele in the genome. If a reporter is present, Cre activity will‘trap’the cell and permanently mark its descendent lineage independent of any further Notch1 activation (Fig. 1A). We have used this line to show that this activity-trap strategy could identify lineages experiencing Notch1 activation (Vooijs et al., 2007).

Despite our success, this NIP-Cre reporter line is relatively insensitive and seemed to predominantly trap cells in which high or repeated activation cycles are known to occur (e.g. endothelium), while missing cells in many tissues known to rely on Notch1 activity [e.g. the hematopoietic system, (Vooijs et al., 2007)]. We speculated that this could be caused by less-efficient transcription from the manipulated allele and reduced activity by the insertion of the 6MT (Vooijs et al., 2007). It was also hypothesized that, in some tissues, sequences required for proper trafficking of Notch to the membrane were lost when NICD was replaced with Cre.

Here, we report that removing the 6MT and adding an additional polyadenylation signal significantly improved sensitivity, allowing us to trap cells experiencing lower Notch activation thresholds. When compared with the original N1IP-Cre reporter (now designated as N1IP::CreLowActivityorN1IP::CreLO), this new line (N1IP::CreHighActivityorN1IP::CreHIallele) traps Notch1 activation

in most tissues known to rely on Notch1, and identifies novel cells utilizing Notch1 during their development and/or maintenance, some of which will be reported elsewhere. Importantly, biochemical analysis indicates that this new allele is cleaved as efficiently as

Received 6 November 2014; Accepted 23 January 2015

1

SAGE Labs, St Louis, MO 63146, USA.2Department of Developmental Biology, Washington University, St Louis, MO 63110, USA.3Division of Developmental Biology, Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH 45229, USA.4Carnegie Institution for Science, Department of Embryology, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA.

*Author for correspondence (Raphael.Kopan@cchmc.org)

© 2015. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd|Development (2015) 142, 1193-1202 doi:10.1242/dev.119529

DEVEL

O

Notch1, supporting our previous observation that Notch trafficking relies on signals coded in the extracellular domain (Liu et al., 2013). This trap line, N1IP::CreLOand the related sibling N1IP::CreERT2 (Liu et al., 2009; Pellegrinet et al., 2011) line, are powerful new tools for mapping alteration in Notch1 activation in vivo as a consequence of genetic or pharmaceutical intervention.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Biochemical analyses of N1IP::Cre constructs demonstrate that a 6MT C-terminal fusion reduces Cre activity five- to tenfold

N1IP::Cre mice contain a 6MT fused to the C-terminus of the Cre recombinase protein (Fig. 1A,E). Similar Cre fusions described elsewhere include CreErt2, in which a tamoxifen-responsive domain controls nuclear entry of Cre (Feil et al., 1996; Zhang

[image:2.612.104.511.58.481.2]et al., 1996). Cre activity is reliant on Tyr 324, located 20 amino acids from the C-terminus (Guo et al., 1997). Given the low labeling index of N1IP::Cre in some tissues (Vooijs et al., 2007), we tested whether this fusion might reflect a negative interference with Cre-recombinase enzymatic activity. To test this hypothesis, we developed anin vitro system to quantify Cre activity in primary cells. First, we prepared reporters for Cre activity by isolating mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from embryos heterozygous for the RosaR26R allele (Soriano, 1999). In these cells,β-galactosidase (lacZ) will be expressed upon Cre-mediated recombination of a single locus (Fig. 1C). Second, we constructed plasmids encoding Cre and Cre-6MT containing a nuclear localization sequence (NLS), followed by an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) and firefly luciferase (Luc, Fig. 1B). In a given transfected cell population, lacZ activity will be a measurable surrogate for Fig. 1. Creation of N1IP::CreHI.(A) Principle of cleavage-dependent Notch reporter. The replacement of Notch intracellular domain with Cre recombinase leads to the release of Cre, but not of NICD, from the cell membrane after ligand-induced S2 and S3 cleavage. Cre will activate reporters, such as RosalacZor Rosa EYFP, which will remain active in all descendants. (B-D) Comparison of the enzymatic activity of Cre and Cre6mt fusion proteins. (B) Structure of the plasmids used in the analysis. (C) Schema of MEF preparation and testing. (D) Comparison ofβ-gal activity in R26R-MEF cells expressing similar levels of luciferase (note that the data are plotted on a log scale). (E) Comparison of N1IP::CreLOand N1IP::CreHItargeted locus. ANK, ankyrin repeats; LNR, Lin-Notch repeat; TM, transmembrane domain; PEST, proline/glutamic acid/serine/threonine-rich motif; 2pA and 3pA, 2× and 3× polyadenylation signal. (F) Comparison of mRNA levels among Notch1, N1IP::CreLOand N1IP::CreHIin 9.5-day embryos. (G) Comparison of released Cre levels between N1IP::CreLOand N1IP::CreHIin newborn kidneys by western blot using anti-V1744 antibody. (H) Quantification of released Cre relative to the released N1ICD in the same sample.

DEVEL

O

recombinase activity within the population, whereas luciferase activity will report relative output from the Cre-expressing plasmids (transfection efficiency), independent of their recombinase activity. When MEFs were transfected with increasing DNA concentrations, luciferase activity scaled linearly throughout the entire range (from 7.8 to 500 µg, supplementary material Fig. S1), demonstrating that Cre and Cre-6MT were expressed at similar levels. However, β-Gal activity in extracts prepared from transfected cells indicated that NLSCre6MT recombinase activity was significantly diminished relative to Cre at every concentration (supplementary material Fig. S1). Notably, measurable β-Gal activity could be detected at the lowest transfected Cre concentration and continued to increase in a relatively linear fashion, whereas NLSCre6MT activity increased only above 60 ng (supplementary material Fig. S1). To compare Cre activity at similar protein concentrations, we transfected the MEFs with plasmid concentrations yielding identical photon flux and measured β-Gal activity (Fig. 1D). Even at this high plasmid concentration a sevenfold difference was noted between Cre and Cre6MT (Fig. 1D). These results indicate that our original strain, N1IP::Cre mice (Vooijs et al., 2007) and, most likely, the related line N1IP::CreERT2(Pellegrinet et al., 2011), under-report Notch activity

in vivo. This conclusion applies to all CreErt2 lines driven by weak promoters, and could explain the differences in labeling observed when different Cre fusion proteins are expressed from the same locus as in Grisanti et al. (2013).

The creation of N1IP::CreHIreporter mice

An unfused activity-trap reporter might be able to trap Notch1 activity at lower thresholds missed with the Cre6MT protein. To generate mice with improved Notch-trap ability, we modified our targeting constructs to create a new line of knock-in reporter mouse, N1IP::creHI (Fig. 1E; supplementary material Fig. S2). First, we removed the 6Myc tag from the targeting construct to restore the original C-terminus. Second, we added an additional polyadenylation signal (AAUAAA) to the SV40 early polyadenylation sequence following

the Cre ORF, thus matching the total number of polyadenylation signals (three) found in the wild-type Notch1 transcript. Finally, we substituted a cytidine for an adenine at position 5178 of exon 28, corresponding to a silent mutation at the third position for L1726 in Notch1 (Fig. 1E; supplementary material Fig. S2). This offers a simple, fast and non-radioactive method to pre-screen embryonic stem cells (ESCs) for homologous recombination with pyrosequencing (Liu et al., 2009), and enabled us to compare the abundance of mRNA produced by each allele (Liu et al., 2013, 2011). We expected these modifications to increase the relative abundance of the N1IP::CreHI mRNA and to fully restore Cre activity.

To directly compare the mRNA level of N1IP::CreHI and N1IP::CreLO, we matedNotch1+/CreHI(N1IP::CreHIheterozygote) to Notch1+/CreLO (N1IP::CreLOheterozygote) mice and collected E9.5Notch1CreHI/CreLOembryos. These animals have no functional NICD and do not survive beyond E10.5.Notch1+/CreHIembryos served as a control. From these, we purified total RNA for RT-PCR and performed pyrosequencing to compute the ratio of adenine (N1IP::CreHI) to cytidine (wild-type Notch1 in Notch1+/CreHI embryos or N1IP::CreLO in Notch1CreHI/CreLO embryos) at

nucleotide 5178 in exon 28. The results show that the addition of the extra polyadenylation signal increases the stability of N1IP::CreHI mRNA ∼twofold, to a level comparable to that of

the endogenousNotch1[Fig. 1F; (Liu et al., 2011)]. To compare the amount of the Cre protein that is released from the cell membrane after ligand binding from the N1IP::CreHI and N1IP::CreLO

proteins, we performed western blot on wild type, N1IP::CreHI heterozygote andN1IP::CreLOheterozygote newborn kidneys with an antibody against cleaved Notch1 (V1744), thus normalizing the level of Cre to the NICD produced from the cleaved endogenous Notch1. Consistently, we found a twofold increase in the abundance of cleaved Cre relative to Cre6MT (Fig. 1G,H).

[image:3.612.49.410.452.734.2]Importantly, because N1IP alleles are cleaved as effectively as the endogenous Notch1 allele in the kidney (Fig. 1G,H), they establish unequivocally that sequences in the intracellular domain

Fig. 2. Comparison of the labeling pattern between N1IP::CreHIand N1IP::CreLOat different embryonic stages.N1IP::CreLO; RosaR26R/R26R

(A-D) andN1IP::CreHI; RosaR26R/R26R

(E-M) embryos at different stages stained with X-gal. White arrowheads, notochord; yellow arrows, intersegmental arteries; black arrowhead in F, ventral half of the developing CNS. (I) Sagittal section of an E15.5N1IP::CreHI; RosaR26R/R26Rembryo stained with X-gal. J and K show coronal sections of E9.5 and E10.5 embryos, respectively. Black arrowheads, notochord. (L) Enlarged view of an E10.5 embryo. Black arrows, intersegmental arteries. (M) Stained sagittal section of the head of a newborn pup. Thyroid gland is labeled with a white arrow.

RESEARCH ARTICLE Development (2015) 142, 1193-1202 doi:10.1242/dev.119529

DEVEL

O

beyond the cleavage site do not play a significant role in regulating the trafficking of Notch proteins to the proper apical membrane domain. This extends the conclusion derived from kidney epithelia (Liu et al., 2013) to the kidney endothelial cells, the main contributor of Notch1 ICD to whole kidney extracts. Whether this is the case in all metazoans or in all mammalian cell types remains to be determined.

Comparing N1IP::CreHIand N1IP::CreLOin vivo

N1IP::CreHI; RosaR26R/R26Rsires were mated withRosaR26R/R26R

dams (Soriano, 1999) to trap cells experiencing Notch1 activation. Consistent with the data showing increased Cre protein level and activity, we found that, throughout early embryonic development, N1IP::CreHI embryos were more intensely labeled by whole-mount β-Gal staining than N1IP:: CreLOembryos (4°C overnight, Fig. 2). Consistent with what we observedin vitro, N1IP::CreHI-trapped cells experienced Notch1 activity earlier than N1IP::CreLOat all embryonic stages (Fig. 2). Under the same X-gal development conditions, N1IP::CreHI; RosaR26R/R26Rembryos contained many labeled cells in the heart

(Fig. 2E, asterisk) and the notochord (Fig. 2E, white arrowhead; Fig. 2J, black arrowhead) by E9.5. By contrast, no signal was detected inN1IP::CreLO; RosaR26R/R26Rembryos before E10.5, when the only labeled cells were found in the heart [Fig. 2A,B; (Vooijs et al., 2007)]. At E10.5, more cells were labeled in N1IP::CreHIhearts (Fig. 2F, asterisk) and most, if not all,

inter-segmental arteries (Fig. 2F, yellow arrows; Fig. 2L, black arrows). This indicates that Notch1 is activated earlier than E10.5 in arterial endothelial cells, consistent with genetic observations and phenotypes (Gridley, 2010). By contrast, the inter-segmental arteries were sparsely labeled in theN1IP::CreLOmice at E11.5 (Fig. 2C). Accordingly, N1IP:CreHI/flox trans-heterozygotes, in which the activated N1IP::Cre excises the floxed Notch1 allele, suffer embryonic lethality at E10.5 due to the developmental failure of the vascular system in the yolk sac and the embryo (Liu et al., 2011), similar to the result of early endothelial cell-specific conditional knockout of Notch1 (Limbourg et al., 2005) with either one of two available Tie2-Cre strains (Kisanuki et al., 2001;

Koni et al., 2001). By contrast, all N1IP:CreLO/flox trans-heterozygotes survive without discernible phenotype to P50 (Liu et al., 2011). Together, these data suggest thatN1IP::CreHI reports the activation of Notch1 in the endothelium with high fidelity, trapping nearly all cells, whereasN1IP::CreLOreported activation only in cells experiencing substantially higher Notch activation levels (Vooijs et al., 2007). Interestingly, removal of ADAM10 with Tie2-Cre (Kisanuki et al., 2001) was not lethal (Zhao et al., 2014), perhaps allowing sufficient activity to persist through an early, crucial developmental window. The use of these lines to elucidate the role of signal strength in endothelial and hematopoietic lineage separation from hemogenic endothelium will be described elsewhere.

At E15.5, staining of sagittal sections showed widespread labeling in the neural tube, brain, retina, major blood vessels, intestine and vertebrae (Fig. 2I), correlating well with the reported role ofNotch1in these tissues. At P0, a majority of the brain is labeled and nerve fibers in the head region can be clearly identified withβ-Gal staining (Fig. 2M). Recently, it has been suggested that Notch signaling regulates thyrocyte differentiation (Carre et al., 2011; Ferretti et al., 2008). Accordingly, we observed widespread labeling in the thyroid gland at P0 (Fig. 2M, white arrow).

To assess the behavior ofN1IP::CreHIwith a different reporter strain, we crossedN1IP::CreHIandN1IP::CreLOwithRosaeYFP/eYFP mice (Srinivas et al., 2001). We collected kidneys at post-natal day 28 ( p28) and compared the labeling patterns in the kidney cortex. The entire CD31+ vascular tree within glomeruli is labeled in bothN1IP::Crelines [Fig. 3, arrows; see also (Liu et al., 2013)], consistent with the robust activation of Notch1 during the development and maintenance of endothelial cells (Gridley, 2010). Despite the activation of Notch1 in the proximal tubule epithelium during kidney development and its known contribution to the maturation of these cells (Surendran et al., 2010a,b), very little labeling is detected within this compartment in N1IP::CreLO; Rosa+/eYFP mice. By contrast, a majority of proximal tubule

[image:4.612.71.547.57.254.2]epithelia are Notch1-lineage positive in N1IP::CreHI;Rosa+/eYFP mice (Fig. 3, arrowheads), consistent with its role in the development and in regulation of tubule diameter (Liu et al., Fig. 3. 6Myc-Tag compromises Notch1-Cre activityin vivo.Kidneys were isolated from P28N1IP::CreLO;Rosa+/eYFP(A-E) andN1IP::CreHI; Rosa+/eYFP

(F-J), and examined for lineage-positive cells in the kidney cortex. Both N1IP::CreLOand N1IP::CreHIlabel CD31+endothelial cells within glomeruli (white arrows) and in vessels (asterisks in A-C, not shown in F-H). InN1IP::CreLOmice, the associated tubular epithelium (Aqp1 positive; D,E) surrounding glomeruli infrequently contains labeled cells (white arrowheads). By contrast, a majority of tubular epithelial cells in N1IP::CreHImice are labeled (I,J). Scale bars: 100 µm.

DEVEL

O

2013; Surendran et al., 2010a). These data demonstrate that removal of the 6MT and addition of a third polyA site result in higher recombinase Cre activity in vivo, consistent with our in vitro findings.

Although these patterns alleviate the concern that N1IP:: CreHI might over-report Notch1 activity, it is possible that a

reporter that recombines at lower Cre concentrations will generate a false-positive signature of Notch1 activity. To evaluate the potential for false positives, we examined the labeling patterns in the most sensitive reporter line we have available, Ai3 (Madisen et al., 2010). The Ai3 reporter recombination and expression are highly efficient and served to determine the false-positive labeling rates in the distal tubules of the kidney, where Notch1 expression is too low to be detected (Liu et al., 2013). In the Ai3 kidneys, a significant number of distal tubule cells experienced N1 activation, but very few connecting segment cells were labeled (Fig. 4). This might indicate a physiological reality in which signal strength was insufficient to divert some cells from assuming a distal fate, or the result of background proteolytic release of Cre. The decline in labeling frequency from the proximal tubules (∼100%) to the thick ascending limb (62.29±5.2%) to the connecting segment (11.18±1.8%) is more consistent with the former possibility; the intense labeling of distal tubule is consistent with the first.

These data demonstrate that theN1IP::CreLOallele only labels the subset of cells that experience high and/or persistent Notch1 activation. Removing the 6MT increased labeling efficiency in many tissues where Notch1 has a known function. It is worth noting that, although N1IP::CreHIexhibits vastly improved sensitivity overN1IP::CreLO,

not all known Notch-mediated decisions are captured. For instance, we did not observe labeling in the somite at E9.5 and E10.5 (Fig. 2E,F,J, K), where Notch1 plays an important role at very low activation levels (Conlon et al., 1995; Huppert et al., 2005; Lewis, 2003).

N1IP::CreHIlabeling patterns in the reproductive organs The Notch signaling pathway plays essential roles in mediating the interactions between the stem cells and their niche in various organs, including the reproductive organs in Drosophila (Kitadate and Kobayashi, 2010; Song et al., 2007; Ward et al., 2006) and C. elegans(Hubbard, 2007). Whereas in theDrosophilaovary the Notch receptor is expressed in the niche, the receptor is required in the germ line stem cells inC. elegans. In rodent ovaries, Notch2 is expressed in granulosa cells and the Jag1 ligand is expressed in the germ cells (Johnson et al., 2001; Vanorny et al., 2014; Xu and Gridley, 2013). The ovary of sexually mature virginN1IP::CreHI; Rosa+/R26Rfemales showed ubiquitous labeling in granulosa cells

(Fig. 5F), suggesting that Notch1 acts with Notch2 in the ovary but is not activated in the oocyte (Vanorny et al., 2014). Accordingly, we did not observe germline inheritance of an active reporter in offspring ofN1IP::CreHI;RosaR26R/R26Rfemales.

[image:5.612.48.339.57.345.2]The role of Notch in the rodent testis remains controversial. Some reports suggest a possible role for Notch1 in the niche during spermatogenesis (Dirami et al., 2001; Hayashi et al., 2001; Murta et al., 2013), but functional studies could not demonstrate an essential function for Notch1 (Batista et al., 2012; Hasegawa et al., 2012). If N1IP::CreHI is activated in germ cells during spermatogenesis, it will result in germline inheritance of an active reporter, manifest in uniform lacZ expression (stained blue by X-gal) in offspring of N1IP::CreHI; RosaR26R/R26R fathers. However, we only saw three blue embryos out of more than 100 embryos that we stained, suggesting that Notch1 activation in germ cells during spermatogenesis is an infrequent event or too low to be detected by this line. Examination of the adult testis revealed extensiveN1IP::CreHIactivation within Sertoli cells (as marked by SOX9 and TUBB3; Fig. 5I), consistent with previous studies showing transgenic Notch Reporter GFP (TNR-GFP) activation in Sertoli cells during multiple developmental stages (Garcia et al., 2013; Hasegawa et al., 2012). There was also N1IP::CreHI Fig. 4. Notch1-Cre activity in the nephron of the adult kidney.

N1IP::CreHIactivity in the distal nephron was detected by the overlap of EYFP with Tamm–Horsfall staining (left panel, the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle); arrows indicate co-labeling of EYFP and Tamm–Horsfall glycoprotein. Clcnkb staining (middle panel) shows distal convoluted tubules (same pattern seen with Cdh1+; CytoK8−). Only a few cells were positive for both Calbindin and EYFP (distal tubule and connecting segment, right panel). Scale bar: 50 µm. 20× magnification.

RESEARCH ARTICLE Development (2015) 142, 1193-1202 doi:10.1242/dev.119529

DEVEL

O

activation within the interstitial compartment of the testis, probably within vascular endothelial cells or perivascular cells, both of which express Notch receptors and activate TNR-GFP during adulthood (DeFalco et al., 2013).

By contrast, widespread labeling was detected as early as at E12.5 in the mesonephric tubules, the precursors of the epididymis (Fig. 5A), persisting to the maturing epididymis (Fig. 5B,C). The Wolffian duct in female embryos was labeled before it degenerates into Gartner’s duct (Fig. 5E). Vasculature at the gonad-mesonephros junction also was labeled (Fig. 5E). Sections of newborn and adult epididymis showed that epithelial cells around the lumen of all major segments, including the initial segment, caput, corpus and tails are labeled, albeit at different frequencies (Fig. 5G,H). Anti-K14 and EYFP double-staining of sections from N1IP::CreHI;Rosa+/eYFPmice showed that all labeled cells are

K14-negative principal cells (Fig. 5J). Stained particles in the lumen of epididymis (Fig. 5K) were negative for DAPI staining, suggesting that they are not sperm but rather epididymosomes, membranous

vesicles that are derived from principal cells of the epididymis (Saez et al., 2003). This is consistent with the idea that Notch1 activation might not occur during spermatogenesis, but instead in the epididymis, which is essential for the maturation of the sperm. However, assignment of functional significance will necessitate further studies.

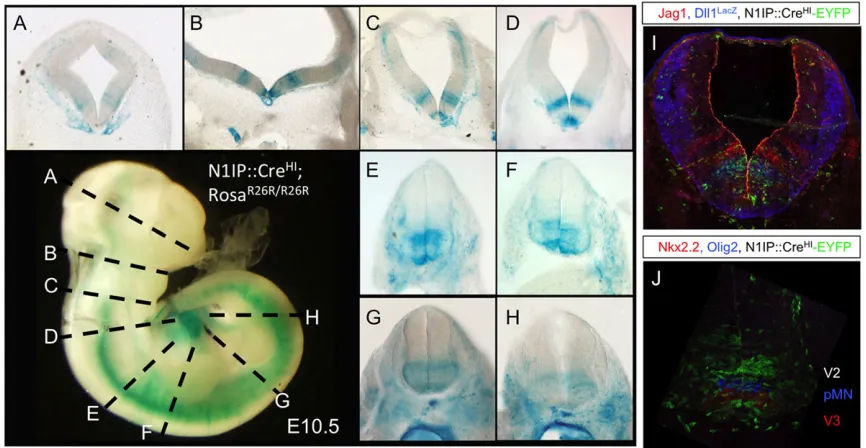

N1IP::CreHIlabeling pattern in the neural tissue

Notch activity is dispensable for establishing the neuroepithelium as all Notch pathway mutants complete this process (de la Pompa et al., 1997; Oka et al., 1995). We noted faint labeling in the ventral half of the developing CNS (black arrow, Fig. 2F). To identify the labeled cells we sectioned E10.5 embryos that had been stained for β-Gal activity, and used a stereoscope to photograph the slices (Fig. 6A-H). Two discrete progenitor domains adjacent to the floor plate were strongly labeled in the diencephalon (Fig. 6A), midbrain (Fig. 6B), hindbrain (Fig. 6C,D) and spinal cord (Fig. 6E-H). Labeling of subpopulations of

early-Fig. 5. Notch1 labeling pattern in the reproductive system.(A-E) Whole-mount staining of gonads from male (A-C) and female (D-E) embryos of indicated age and genotype. (F) X-gal staining of an ovary from P53 virgin

R26R, N1IP::CreHIfemale. (G,H)

X-gal-stained section through epididymis from immature (G) and mature (H) R26R, N1IP:: CreHImale. (I) Immunofluorescence staining of adultN1IP::CreHI;Rosa+/eYFPtestis shows

high levels of Cre activity in Sertoli cells identified with the Sertoli-specific markers Sox9 and TUBB3. Note the colocalization of EYFP with Sox9 or TUBB3. Scale bar: 100 µm. (J) Co-staining of K14 and EYFP in different segments of the epididymis from

N1IP::CreHI; Rosa+/eYFPmale identifies labeled cells as principal cells. (K) GFP+ epididymosome particles in the lumen of epididymis fromN1IP::CreHI; Rosa+/eYFPmale are negative for DAPI. Ep, epididymis; Gd, Gartner’s duct; Kd, kidney; Ms, metanephros; Ov, ovary; Te, testis; Wd, Wolffian duct.

DEVEL

O

[image:6.612.50.401.56.520.2]born neurons in the dorsal aspect of the midbrain and hindbrain was also detectable (Fig. 6B-D). This stripe pattern had been observed previously with Dll1 and Jagged1 expression in the chick hindbrain and neural tube (Marklund et al., 2010; Myat et al., 1996). To align Notch activity stripes with its ligand we crossed Dll1+/lacZ (Hrabe de Angelis et al., 1997) mice with N1IP::CreHI; RosaeYFP/eYFP mice to generate E10.5 embryos

heterozygous for Dll1, Notch1 and Rosa-eYFP. Staining forlacZ (Dll1 expression, Fig. 6I), EYFP (Cre activity) and Jagged1 confirmed that the cells experiencing Notch activation overlapped with the ligand Dll1 (Fig. 6I). To identify the cells that experienced high levels of Notch1 activity we stained a section of the neural tube from N1IP::CreHI; RosaeYFP/eYFP mice with Olig2 and Nkx2.2, which confirmed that progenitors in the pV2 and pV3 domains were labeled much more intensely than those in the adjacent pMN and pV1 domains (Fig. 6J). We and others have shown previously that Notch1 signaling was necessary to specify neuronal subtypes, in particular V2 neurons and motor neurons in the spinal chord (Del Barrio et al., 2007; Misra et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2006). It would be interesting to investigate whether V2 neuron specification requires higher Notch1 signal strength than other neuronal cell types.

In the CNS, neural progenitors undergo multiple rounds of asymmetric division. Notch signaling oscillates to keep progenitors cycling between committed progenitor state (Hes target gene expression detected, proneural genes repressed) and pre-neuron [ proneural gene expression detected, Hes1 repressed; (Imayoshi et al., 2013; Kobayashi and Kageyama, 2010; Shimojo et al., 2008, 2011)]. After each division, the neuron daughter cell is thought to activate Notch in its sister to reinforce the progenitor fate. A perfect activity trap would label progenitors after the first Notch-dependent decision, trapping all of their subsequent descendants (Fig. 7A). Analysis of cortical layers fromN1IP::CreHI; Rosa+/Ai3(Fig. 7B; supplementary material Fig. S3) shows co-labeling of EYFP (N1IP::CreHIactivity) and Foxp1 (a neuronal marker for late-born upper layer neurons: Foxp1 labels neurons in layers II-IVa) in E15.5

cortical neurons (Fig. 7B,B′; supplementary material Fig. S3). EYFP labeling was also detected in FoxP1–, earlier born neurons and in stem/progenitor cells in the ventricular and subventricular zones (VZ/SVZ) (supplementary material Fig. S4; arrows). By contrast, we detected no EYFP labeling in Foxp1+cortical neurons of N1IP::CreLO; Rosa+/Ai3 embryos (Fig. 7C; supplementary material Fig. S3). In addition, striatal projection neurons were labeled very efficiently in N1IP::CreHI; Rosa+/Ai3 but only marginally in N1IP::CreLO; Rosa+/Ai3(Fig. 7; supplementary material Fig. S4). These data underscore the differences in activation threshold between Cre and Cre6MT (and, by inference, CreERT2).

The images in supplementary material Fig. S3 suggest that EYFP labeling is denser in upper layer neurons than in lower layer neurons and in progenitors located in the neocortex VZ/SVZ. Because Notch1 signaling is thought to be activated in every asymmetric progenitor division (de la Pompa et al., 1997; Imayoshi et al., 2010), two possible scenarios could fit this pattern. First, a common progenitor pool generates both lower layer (early) and upper layer (late) neurons, and late-stage progenitors receive stronger Notch1 signals. Alternatively, the sensitive trap allele is still not sensitive enough, and significant labeling requires gradual accumulation of Cre protein over time, and thus favors late-stage progenitors that produce upper layer neurons. We cannot rule out a third possibility that separate progenitor pools contribute to lower and upper layer neurons, with stronger signaling through the Notch1 receptor in the latter.

Summary

[image:7.612.89.522.59.283.2]Here, we demonstrate that Cre activity is compromised by fusion of additional amino acids to the C-terminus. This observation implies that all Ert2 fusion proteins are less active than Cre even when equal nuclear concentrations are achieved, as shown in Grisanti et al. (2013). The comparison between the two N1IP::Cre lines reveals that Notch1 proteolysis, and thus signal strength, vary with time within the same tissue (e.g. early- versus late-born cortical neurons, Fig. 6. Notch1-Cre activity in the developing CNS and neural tube defines a subset of neurons.(A-H) Whole-mount stained E10.5N1IP::CreHI,Rosa+/R26R

male embryos were cut into slices showing the diencephalon (A), midbrain (B), hindbrain (C,D) and spinal cord (E-H), and were photographed on a stereoscope. (I) History of Notch activity detected with EYFP, Dll1 distribution withlacZand Jagged1 expression with antibody staining inN1IP::CreHI;Rosa+/eYFP;Dll+/lacZ. (J) EYFP, Olig2 and Nkx2.2 staining identifies EYFP+progenitors as V2 neurons.

RESEARCH ARTICLE Development (2015) 142, 1193-1202 doi:10.1242/dev.119529

DEVEL

O

or anterior versus posterior stem cells along the intestine). Whether the increase in signal strength is a consequence of unrelated biology or an important requirement for the Notch signaling pathway remains to be determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS Preparation of MEF cells

MEF cells were prepared under sterile conditions using a modified protocol based on Takahashi et al. (2007) and Xu (2005). Briefly,RosaR26R/R26Rdams were crossed to a CD1 sire and embryos (Rosa+/R26R) were collected at E13.5.

Head, visceral organs and the urogenital system were removed. The remaining tissues were pooled, washed three times with PBS and minced into∼2 mm pieces, using a sterile razor blade in a 100 mm diameter dish containing 20 ml of warm Trypsin-EDTA (∼25 cuts per embryo). The cell mixture was pipetted repeatedly with a 25 ml pipette and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. After incubation, 10 ml of fresh Trypsin-EDTA was added, the tissue was further dispersed using a 10 ml pipette and placed at 37°C for an additional 15 min. The final cell mixture was transferred to a 50 ml conical tube, 20 ml of MEF medium (DMEM, 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 1000 U/ml penicillin and 1000 µg/ml streptomycin) was added to total volume of 50 ml, and spun down at 1500g for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded and the cell pellet resuspended in 1 ml of MEF medium/embryo equivalent. One milliliter of cell supernatant was plated in T75 flasks with 9 ml of MEF medium and incubated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. The next day, cells were washed once with PBS to remove dead/non-adherent cells and fresh medium was added. Cells were frozen at passage 1. All experiments were performed on cells expanded to passage 3 (P3).

Transfection of MEF cells

For transfection, 3.75×104 cells/well P3 MEFs were plated in the afternoon before transfection in 24-well tissue culture plates with 500 µl of MEF medium (without penicillin/streptomycin). Transfection was performed using the Lipofectamine LTX system (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For each well, 0.5 µg total DNA (with the empty pCS2 vector added to reach the final concentration), 3.25μl of LTX reagent and PLUS reagent at a 1:1 ratio with DNA were used. The transfection mixture was incubated with the cells at 37°C for 18 h and replaced with fresh MEF medium. In control experiments using GFP plasmids, ∼70% transfection efficiency was observed. Firefly luciferase and β-gal activity were measured 24 h later, as previously described (Ilagan et al., 2011).

Generation of N1IP::CreHIknock-in mice

In brief, the early SV40 polyadenylation sequence with one extra artificially introduced polyadenylation signal (AATAAA) was cloned in front of the FRT-flanked-neomycin selective cassette. The silent mutation in L1726 was introduced with a site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) into the SKB-L genomic clone that encompasses mouse Notch1 exons 26-32 (Vooijs et al., 2007). The SgrAI/SalI-digested NLScre fragment and the SalI/BglII-digested SV40 polyadenylation sequence-FRT-neo cassette were then cloned into SKB-L through theSgrAI/BamHI site to replace the last 105 bases of exon 28 and to delete exons 29 and 30 ( please note thatBamHI andBglII share a compatible cohesive end, and after ligation theBamHI site is lost) (supplementary material Fig. S2). This plasmid was then sequenced and linearized with EcoRI for ESC electroporation.

ESC targeting and screening

We targeted theNotch1locus using 129X1Sv/J-derived SCC10 ESCs (for further information regarding this line see http://escore.im.wustl.edu/ SubMenu_celllines/wtEScell_linesSCC10.html) and selected for G418-resistant ESC colonies. Cells were first pre-screened with pyroscreening, utilizing the C5178A polymorphism (Liu et al., 2009), and those with a C/A ratio between 40 and 60% at this position were further screened by both long-range PCR and Southern blot to confirm bona fide homologous recombinants [HR, (Liu et al., 2009); supplementary material Fig. S2)]. Positive HRs were karyotyped, and one line (ES190) was injected into C57B6 blastocysts. The resulting chimera male mice were mated to wild-type C57B6 female mice. F1 males were mated to FRT deleter mice (Rodriguez et al., 2000) to remove the FRT-flanked neomycin cassette.

Western blot

Western blot was performed as described in Liu et al. (2013). Rabbit monoclonal anti-cleaved Notch1 (anti-V1744, Cell Signaling) antibodies were used at 1:1000 dilution.

X-gal staining

[image:8.612.82.535.57.250.2]X-gal staining was performed as described in Vooijs et al. (2007). Briefly, embryos or freshly dissected tissues were fixed in 4% PFA in 1× PBS supplemented with 2 mM MgCl2on ice for 1-2 h and washed with 1× PBS +2 mM MgCl2. For whole-mount staining, embryos were developed in X-gal staining solution at 4°C overnight; for frozen section staining, tissues were immersed in 30% sucrose in 1× PBS+2 mM MgCl2overnight and Fig. 7. Notch1-Cre activity in neuronal precursors.Coronal sections through the telencephalic region at E15.5 detected EYFP staining as an indication of Notch1-Cre activity inRosa+/Ai3developing neurons. (A) Schematic illustrating the likelihood that a precursor will be labeled by N1IP::CreLOor N1IP::CreHI. The probability is depicted as a gradient. G, glia; ND, not detected. (B,C) The neuronal marker FoxP1 labels upper cortical layers (boxed regions in B′,C′) and striatal projection neurons (boxed regions in B″,C″) in the N1IP::CreHI(B) and N1IP::CreLO(C). See supplementary material Fig. S3 for higher magnification view of the boxed regions.

DEVEL

O

embedded in optimal cutting medium (OCT, Tissue-Tek) and stained in X-gal staining solution at 37°C overnight or until signal was detected.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described in Liu et al. (2013). Briefly, frozen sections were blocked with normal donkey serum and then incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Following three times washing with 1× PBS, the sections were incubated with fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies, washed with 1× PBS and mounted for imaging. The following primary antibodies were used: chicken anti-GFP (1:500; Aves Lab, GFP-1020) or rabbit anti-GFP (1:1000; Invitrogen, A11122), rabbit Foxp1 (1:2000; Abcam, ab16645), mouse anti-Calbindin (1:500; Sigma-Aldrich, C9848), rabbit anti-Tamm–Horsfall protein (THP) (1:250; Biomedical Technologies, BT-590), rabbit anti-Clcnkb (1:200; GeneTex, GTX47709), rabbit anti-olig2 (1:500; Millipore, AB9610), goat anti-Nkx2.2 (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotech, SC-15015), chicken anti-K14 (1:200; a generous gift from Dr Julie Segre, National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health), goat anti-Jag1 (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotech, SC-6011), rabbit anti-β-galactosidase (1:5000; Cappel Labs/MP Biomedicals, 08559761), rat anti-CD31 (1:100; BD Bioscience, 550274), goat anti-aquaporin-2 (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotech, SC-9882), rabbit Sox9 (1:4000; Millipore, #AB5535) and mouse anti-TUBB3 (TUJ1) (1:1000; Covance, #MMS-435P). Images were acquired with either ApoTome2 (Zeiss) or a Nikon 90i upright wide-field microscope. Images were processed using Nikon Elements software, Photoshop or Canvas.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Kopan laboratory for many fruitful discussions and Ms Mary Fulbright for expert technical assistance. Special thanks to Drs Tony De Falco (reproductive system), Kenny Campbell and Masato Nakafuku (central nervous system) for expert advice and for critical reading of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Z.L. and R.K. conceived the project and wrote the manuscript; Z.L., E.B., S.B., S.C. designed and performed experiments; M.T., Y.G. and R.G. performed experiments.

Funding

Y.G. was supported fully, and R.K., Z.L., S.C. and M.T. were supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [R01GM55479 awarded to R.K.]. S.B. and R.G. were supported by the NIH [R01DK066408 awarded to R.K.]. R.K. and E.B. were supported in part by the William K. Schubert Chair for Pediatric Research. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at

http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.119529/-/DC1

References

Artavanis-Tsakonas, S., Rand, M. D. and Lake, R. J.(1999). Notch signaling: cell fate control and signal integration in development.Science284, 770-776.

Batista, F., Lu, L., Williams, S. A. and Stanley, P.(2012). Complex N-glycans are essential, but core 1 and 2 mucin O-glycans, O-fucose glycans, and NOTCH1 are dispensable, for mammalian spermatogenesis.Biol. Reprod.86, 179.

Carre, A., Rachdi, L., Tron, E., Richard, B., Castanet, M., Schlumberger, M., Bidart, J.-M., Szinnai, G. and Polak, M.(2011). Hes1 is required for appropriate morphogenesis and differentiation during mouse thyroid gland development.

PLoS ONE6, e16752.

Conlon, R. A., Reaume, A. G. and Rossant, J.(1995). Notch1 is required for the coordinate segmentation of somites.Development121, 1533-1545.

de la Pompa, J. L., Wakeham, A., Correia, K. M., Samper, E., Brown, S., Aguilera, R. J., Nakano, T., Honjo, T., Mak, T. W., Rossant, J. et al.(1997). Conservation of the Notch signalling pathway in mammalian neurogenesis.

Development124, 1139-1148.

DeFalco, T., Saraswathula, A., Briot, A., Iruela-Arispe, M. L. and Capel, B.

(2013). Testosterone levels influence mouse fetal Leydig cell progenitors through notch signaling.Biol. Reprod.88, 91.

Del Barrio, M. G., Taveira-Marques, R., Muroyama, Y., Yuk, D.-I., Li, S., Wines-Samuelson, M., Shen, J., Smith, H. K., Xiang, M., Rowitch, D. et al.(2007). A regulatory network involving Foxn4, Mash1 and delta-like 4/Notch1 generates V2a and V2b spinal interneurons from a common progenitor pool.Development

134, 3427-3436.

Demehri, S., Liu, Z., Lee, J., Lin, M.-H., Crosby, S. D., Roberts, C. J., Grigsby, P. W., Miner, J. H., Farr, A. G. and Kopan, R.(2008). Notch-deficient skin induces a lethal systemic B-lymphoproliferative disorder by secreting TSLP, a sentinel for epidermal integrity.PLoS Biol.6, e123.

Dirami, G., Ravindranath, N., Achi, M. V. and Dym, M.(2001). Expression of Notch pathway components in spermatogonia and Sertoli cells of neonatal mice.

J. Androl.22, 944-952.

Feil, R., Brocard, J., Mascrez, B., LeMeur, M., Metzger, D. and Chambon, P.

(1996). Ligand-activated site-specific recombination in mice.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA93, 10887-10890.

Ferretti, E., Tosi, E., Po, A., Scipioni, A., Morisi, R., Espinola, M. S., Russo, D., Durante, C., Schlumberger, M., Screpanti, I. et al.(2008). Notch signaling is involved in expression of thyrocyte differentiation markers and is down-regulated in thyroid tumors.J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.93, 4080-4087.

Gale, N. W., Dominguez, M. G., Noguera, I., Pan, L., Hughes, V., Valenzuela, D. M., Murphy, A. J., Adams, N. C., Lin, H. C., Holash, J. et al.(2004). Haploinsufficiency of delta-like 4 ligand results in embryonic lethality due to major defects in arterial and vascular development.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA101, 15949-15954.

Garcia, T. X., DeFalco, T., Capel, B. and Hofmann, M.-C.(2013). Constitutive activation of NOTCH1 signaling in Sertoli cells causes gonocyte exit from quiescence.Dev. Biol.377, 188-201.

Gridley, T.(2010). Notch signaling in the vasculature.Curr. Top. Dev. Biol.92, 277-309.

Grisanti, L., Clavel, C., Cai, X., Rezza, A., Tsai, S.-Y., Sennett, R., Mumau, M., Cai, C.-L. and Rendl, M.(2013). Tbx18 targets dermal condensates for labeling, isolation, and gene ablation during embryonic hair follicle formation.J. Invest. Dermatol.133, 344-353.

Groot, A. J., Cobzaru, C., Weber, S., Saftig, P., Blobel, C. P., Kopan, R., Vooijs, M. and Franzke, C.-W. (2013). Epidermal ADAM17 is dispensable for notch activation.J. Invest. Dermatol.133, 2286-2288.

Guo, F., Gopaul, D. N. and van Duyne, G. D.(1997). Structure of Cre recombinase complexed with DNA in a site-specific recombination synapse.Nature389, 40-46.

Hamada, Y., Kadokawa, Y., Okabe, M., Ikawa, M., Coleman, J. R. and Tsujimoto, Y.

(1999). Mutation in ankyrin repeats of the mouse Notch2 gene induces early embryonic lethality.Development126, 3415-3424.

Hasegawa, K., Okamura, Y. and Saga, Y.(2012). Notch signaling in Sertoli cells regulates cyclical gene expression of Hes1 but is dispensable for mouse spermatogenesis.Mol. Cell. Biol.32, 206-215.

Hayashi, T., Kageyama, Y., Ishizaka, K., Xia, G., Kihara, K. and Oshima, H.

(2001). Requirement of Notch 1 and its ligand jagged 2 expressions for spermatogenesis in rat and human testes.J. Androl.22, 999-1011.

Hrabe˘de Angelis, M., Mclntyre, J.II and Gossler, A.(1997). Maintenance of somite borders in mice requires the Delta homologue Dll1.Nature386, 717-721.

Hubbard, E. J. A.(2007). Caenorhabditis elegans germ line: a model for stem cell biology.Dev. Dyn.236, 3343-3357.

Huppert, S. S., Ilagan, M. X. G., De Strooper, B. and Kopan, R.(2005). Analysis of Notch function in presomitic mesoderm suggests aγ-secretase-independent role for presenilins in somite differentiation.Dev. Cell8, 677-688.

Ilagan, M. X. G., Lim, S., Fulbright, M., Piwnica-Worms, D. and Kopan, R.(2011). Real-time imaging of notch activation with a luciferase complementation-based reporter.Sci. Signal.4, rs7.

Imayoshi, I., Sakamoto, M., Yamaguchi, M., Mori, K. and Kageyama, R.(2010). Essential roles of Notch signaling in maintenance of neural stem cells in developing and adult brains.J. Neurosci.30, 3489-3498.

Imayoshi, I., Shimojo, H., Sakamoto, M., Ohtsuka, T. and Kageyama, R.(2013). Genetic visualization of notch signaling in mammalian neurogenesis.Cell. Mol. Life Sci.70, 2045-2057.

Johnson, J., Espinoza, T., McGaughey, R. W., Rawls, A. and Wilson-Rawls, J.

(2001). Notch pathway genes are expressed in mammalian ovarian follicles.

Mech. Dev.109, 355-361.

Kisanuki, Y. Y., Hammer, R. E., Miyazaki, J.-i., Williams, S. C., Richardson, J. A. and Yanagisawa, M. (2001). Tie2-Cre transgenic mice: a new model for endothelial cell-lineage analysis in vivo.Dev. Biol.230, 230-242.

Kitadate, Y. and Kobayashi, S. (2010). Notch and Egfr signaling act antagonistically to regulate germ-line stem cell niche formation in Drosophila male embryonic gonads.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA107, 14241-14246.

Kobayashi, T. and Kageyama, R.(2010). Hes1 oscillation: making variable choices for stem cell differentiation.Cell Cycle9, 207-208.

Koch, U. and Radtke, F.(2010). Notch signaling in solid tumors.Curr. Top. Dev. Biol.92, 411-455.

Koni, P. A., Joshi, S. K., Temann, U.-A., Olson, D., Burkly, L. and Flavell, R. A.

(2001). Conditional vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 deletion in mice: impaired lymphocyte migration to bone marrow.J. Exp. Med.193, 741-754.

RESEARCH ARTICLE Development (2015) 142, 1193-1202 doi:10.1242/dev.119529

DEVEL

O

Kopan, R. and Ilagan, M. X. G.(2009). The canonical Notch signaling pathway: unfolding the activation mechanism.Cell137, 216-233.

Lewis, J.(2003). Autoinhibition with transcriptional delay: a simple mechanism for the zebrafish somitogenesis oscillator.Curr. Biol.13, 1398-1408.

Limbourg, F. P., Takeshita, K., Radtke, F., Bronson, R. T., Chin, M. T. and Liao, J. K.(2005). Essential role of endothelial Notch1 in angiogenesis.Circulation111, 1826-1832.

Liu, Z., Obenauf, A. C., Speicher, M. R. and Kopan, R.(2009). Rapid identification of homologous recombinants and determination of gene copy number with reference/query pyrosequencing (RQPS).Genome Res.19, 2081-2089.

Liu, Z., Turkoz, A., Jackson, E. N., Corbo, J. C., Engelbach, J. A., Garbow, J. R., Piwnica-Worms, D. R. and Kopan, R.(2011). Notch1 loss of heterozygosity causes vascular tumors and lethal hemorrhage in mice.J. Clin. Invest.121, 800-808.

Liu, Z., Chen, S., Boyle, S., Zhu, Y., Zhang, A., Piwnica-Worms, D. R., Ilagan, M. X. G. and Kopan, R.(2013). The extracellular domain of Notch2 increases its cell-surface abundance and ligand responsiveness during kidney.Dev. Cell25, 585-598.

Madisen, L., Zwingman, T. A., Sunkin, S. M., Oh, S. W., Zariwala, H. A., Gu, H., Ng, L. L., Palmiter, R. D., Hawrylycz, M. J., Jones, A. R. et al.(2010). A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain.Nat. Neurosci.13, 133-140.

Marklund, U., Hansson, E. M., Sundstrom, E., de Angelis, M. H., Przemeck, G. K. H., Lendahl, U., Muhr, J. and Ericson, J.(2010). Domain-specific control of neurogenesis achieved through patterned regulation of Notch ligand expression.

Development137, 437-445.

Misra, K., Luo, H., Li, S., Matise, M. and Xiang, M.(2014). Asymmetric activation of Dll4-Notch signaling by Foxn4 and proneural factors activates BMP/TGFbeta signaling to specify V2b interneurons in the spinal cord. Development 141, 187-198.

Mumm, J. S., Schroeter, E. H., Saxena, M. T., Griesemer, A., Tian, X., Pan, D. J., Ray, W. J. and Kopan, R. (2000). A ligand-induced extracellular cleavage regulates gamma-secretase-like proteolytic activation of Notch1. Mol. Cell5, 197-206.

Murta, D., Batista, M., Silva, E., Trindade, A., Henrique, D., Duarte, A. and Lopes-da-Costa, L. (2013). Dynamics of Notch pathway expression during mouse testis post-natal development and along the spermatogenic cycle.PLoS ONE8, e72767.

Myat, A., Henrique, D., Ish-Horowicz, D. and Lewis, J.(1996). A chick homologue of serrate and its relationship with Notch and delta homologues during central neurogenesis.Dev. Biol.174, 233-247.

Oka, C., Nakano, T., Wakeham, A., de la Pompa, J. A., Mori, C., Sakai, T., Okazaki, S., Kawaichi, M., Shiota, K., Mak, T. W. and Honjo, T. (1995). Disruption of the mouse RBP-Jkappa gene results in early embryonic death.

Development121, 3291-3301.

Pellegrinet, L., Rodilla, V., Liu, Z., Chen, S., Koch, U., Espinosa, L., Kaestner, K. H., Kopan, R., Lewis, J. and Radtke, F.(2011). Dll1- and Dll4-mediated Notch signaling are required for homeostasis of intestinal stem cells.Gastroenterology

140, 1230-1240.e7.

Penton, A. L., Leonard, L. D. and Spinner, N. B.(2012). Notch signaling in human development and disease.Semin. Cell Dev. Biol.23, 450-457.

Rodriguez, C. I., Buchholz, F., Galloway, J., Sequerra, R., Kasper, J., Ayala, R., Stewart, A. F. and Dymecki, S. M.(2000). High-efficiency deleter mice show that FLPe is an alternative to Cre-loxP.Nat. Genet.25, 139-140.

Saez, F., Frenette, G. and Sullivan, R.(2003). Epididymosomes and prostasomes: their roles in posttesticular maturation of the sperm cells.J. Androl.24, 149-154.

Shimojo, H., Ohtsuka, T. and Kageyama, R.(2008). Oscillations in notch signaling regulate maintenance of neural progenitors.Neuron58, 52-64.

Shimojo, H., Ohtsuka, T. and Kageyama, R.(2011). Dynamic expression of notch signaling genes in neural stem/progenitor cells.Front. Neurosci.5, 78.

Song, X., Call, G. B., Kirilly, D. and Xie, T.(2007). Notch signaling controls germline stem cell niche formation in the Drosophila ovary.Development134, 1071-1080.

Soriano, P.(1999). Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain.Nat. Genet.21, 70-71.

Srinivas, S., Watanabe, T., Lin, C.-S., William, C. M., Tanabe, Y., Jessell, T. M. and Costantini, F.(2001). Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus.BMC Dev. Biol.1, 4.

Surendran, K., Boyle, S., Barak, H., Kim, M., Stomberski, C., McCright, B. and Kopan, R.(2010a). The contribution of Notch1 to nephron segmentation in the developing kidney is revealed in a sensitized Notch2 background and can be augmented by reducing Mint dosage.Dev. Biol.337, 386-395.

Surendran, K., Selassie, M., Liapis, H., Krigman, H. and Kopan, R.(2010b). Reduced Notch signaling leads to renal cysts and papillary microadenomas.

J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.21, 819-832.

Takahashi, K., Okita, K., Nakagawa, M. and Yamanaka, S.(2007). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from fibroblast cultures.Nat. Protoc.2, 3081-3089.

van Tetering, G., van Diest, P., Verlaan, I., van der Wall, E., Kopan, R. and Vooijs, M. (2009). Metalloprotease ADAM10 is required for Notch1 site 2 cleavage.J. Biol. Chem.284, 31018-31027.

Vanorny, D. A., Prasasya, R. D., Chalpe, A. J., Kilen, S. M. and Mayo, K. E.

(2014). Notch signaling regulates ovarian follicle formation and coordinates follicular growth.Mol. Endocrinol.28, 499-511.

Vooijs, M., Ong, C.-T., Hadland, B., Huppert, S., Liu, Z., Korving, J., van den Born, M., Stappenbeck, T., Wu, Y., Clevers, H. et al.(2007). Mapping the consequence of Notch1 proteolysis in vivo with NIP-CRE.Development134, 535-544.

Ward, E. J., Shcherbata, H. R., Reynolds, S. H., Fischer, K. A., Hatfield, S. D. and Ruohola-Baker, H.(2006). Stem cells signal to the niche through the Notch pathway in the Drosophila ovary.Curr. Biol.16, 2352-2358.

Xu, J. (2005). Preparation, culture, and immortalization of mouse embryonic fibroblasts.Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol.Chapter 28, unit 28.1.

Xu, J. and Gridley, T.(2013). Notch2 is required in somatic cells for breakdown of ovarian germ-cell nests and formation of primordial follicles.BMC Biol.11, 13.

Yang, X., Tomita, T., Wines-Samuelson, M., Beglopoulos, V., Tansey, M. G., Kopan, R. and Shen, J.(2006). Notch1 signaling influences V2 interneuron and motor neuron development in the spinal cord.Dev. Neurosci.28, 102-117.

Zhang, Y., Riesterer, C., Ayrall, A.-M., Sablitzky, F., Littlewood, T. D. and Reth, M.(1996). Inducible site-directed recombination in mouse embryonic stem cells.

Nucleic Acids Res.24, 543-548.

Zhao, R., Wang, A., Hall, K. C., Otero, M., Weskamp, G., Zhao, B., Hill, D., Goldring, M. B., Glomski, K. and Blobel, C. P.(2014). Lack of ADAM10 in endothelial cells affects osteoclasts at the chondro-osseus junction.J. Orthop. Res.32, 224-230.