Clinical Expert Series

Role of Hormone Therapy in the

Management of Menopause

Jan L. Shifren,

MD, and Isaac Schiff, MDThere are many options available to address the quality of life and health concerns of menopausal women. The principal indication for hormone therapy (HT) is the treatment of vasomotor symptoms, and benefits generally outweigh risks for healthy women with bothersome symptoms who elect HT at the time of menopause. Although HT increases the risk of coronary heart disease, recent analyses confirm that this increased risk occurs principally in older women and those a number of years beyond menopause. These findings do not support a role for HT in the prevention of heart disease but provide reassurance regarding the safety of use for hot flushes and night sweats in otherwise healthy women at the menopausal transition. An increased risk of breast cancer with extended use is another reason short-term treatment is advised. Hormone therapy prevents and treats osteoporosis but is rarely used solely for this indication. If only vaginal symptoms are present, low-dose local estrogen therapy is preferred. Contraindications to HT use include breast or endome-trial cancer, cardiovascular disease, thromboembolic disorders, and active liver disease. Alternatives to HT should be advised for women with or at increased risk for these disorders. The lowest effective estrogen dose should be provided for the shortest duration necessary because risks increase with increasing age, time since menopause, and duration of use. Women must be informed of the potential benefits and risks of all therapeutic options, and care should be individualized, based on a woman’s medical history, needs, and preferences. (Obstet Gynecol 2010;115:839–55)

A

woman in the developed world likely will spend greater than a third of her life beyond meno-pause, so the symptoms that accompany menopause and the morbidities associated with aging are of increasing importance in women’s health. Enthusiasm for the use of estrogen therapy (ET) for the treatmentof menopausal symptoms has varied widely over the past 50 years. Estrogen was initially prescribed as an effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms in the 1960s. By the end of that decade, indications for estrogen use expanded to include remaining “femi-nine forever,” as popularized by the book by Robert Wilson, MD.1Menopause was described as a

prevent-able hormone deficiency, and the following was stated of women using ET: “Instead of being con-demned to witness the death of their own woman-hood, they will remain fully feminine—physically and emotionally—for as long as they live . . .Menopause is curable.” The use of estrogen for menopausal symp-toms declined in the mid-1970s, when endometrial cancer was linked to unopposed estrogen use, but increased again in the 1980s, when it was determined that the addition of progestin use was protective. Prevention of osteoporosis also was identified as an important benefit of ET at that time.

Indications for hormone therapy (HT) then gradually expanded beyond the treatment of

meno-From the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, Harvard Medical School, and Vincent Obstetrics and Gynecology Service, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Continuing medical education is available for this article at http://links.lww. com/AOG/A166.

Corresponding author: Jan L. Shifren, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Vincent Obstetrics and Gynecology Service, 55 Fruit Street, YAW 10A, Boston, MA 02114; e-mail: jshifren@partners.org.

Financial Disclosure

Dr. Shifren serves as a scientific advisory board member for the New England Research Institutes. She has been a research study consultant for Eli Lily & Co. (Indianapolis, Indiana) and Boehringer Ingelheim (Ingelheim, Germany). She also has received research support from Proctor & Gamble Pharmaceuticals (Cincinnati, Ohio). The other author did not report any potential conflicts of interest. © 2010 by The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

pausal symptoms to include prevention of the dis-eases of aging. A series of well-designed observa-tional studies identified a significant reduction in the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) in HT users. Because cardiovascular disease is the number one killer of women, HT often was recommended for disease prevention in postmenopausal women, even in the absence of vasomotor symptoms.

With the first publication of the results of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trial in 2002, the use of HT declined dramatically. The WHI random-ized controlled trial enrolled approximately 16,000 women nationwide, between the ages of 50 and 79 years, with an average age of 63 years. The major goal of the study was to determine whether combined estrogen and progestin therapy prevented heart dis-ease. A global index was designed balancing risks and benefits to include CHD, breast cancer, stroke, pul-monary embolism (PE), endometrial cancer, colorec-tal cancer, hip fracture, and death caused by other causes. Approximately 11,000 women without a uterus participated in a separate WHI study and were randomly assigned to either ET alone or placebo.

Although many clinicians criticize the predom-inance of older women in the WHI studies, it is important to realize that these studies were not designed to examine the risks and benefits of HT use for symptomatic women in early menopause. Given the positive results of observational studies, this balance of risks and benefits for HT use needed to be addressed in older women, those at increased risk for CHD who would benefit most from a preventive strategy.

The WHI trial of combined estrogen and pro-gestin therapy compared with placebo showed that not only did combined estrogen and progestin therapy not prevent heart disease in healthy women, it actually resulted in a small increased risk.2 The results indicated that HT should not be

initiated or continued for primary prevention of CHD. Although this was the principal conclusion of the trial, the results led to the restriction of HT use even for healthy women with bothersome vasomo-tor symptoms at the time of menopause.

Recently, reanalysis of data from the WHI has confirmed that the increased risk of CHD occurs principally in older women and those a number of years beyond menopause. In a secondary analysis of data from the combined WHI trials, no increased risk of CHD was seen in women between the ages 50 and 59 years or in those within 10 years of menopause.3 Although stroke was increased with

HT, regardless of age or years since menopause, the

absolute excess risk of stroke in the younger women was minimal. These data do not support a role for HT in the prevention of heart disease, but they do provide reassurance regarding the cardiovascular safety of HT use for bothersome hot flushes and night sweats in otherwise healthy women at the time of the menopausal transition.

Major health concerns of menopausal women include vasomotor symptoms, urogenital atrophy, osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, cancer, cogni-tion, and mood (Fig. 1). Each of these problems will be reviewed, specifically addressing the role of HT and alternatives. Given recent findings, specifically regarding the effect of the timing of HT initiation on CHD risk, it seems appropriate to reassess the clini-cian’s approach to menopause in the wake of the recent reanalysis of the WHI.

HEALTH CONCERNS OF MENOPAUSAL WOMEN AND TREATMENT OPTIONS Vasomotor Symptoms

Vasomotor symptoms, including both hot flushes and night sweats, are the primary reason women seek care at the time of menopause. These symptoms often are disruptive, interfering with daily activities, work, and sleep.4 Vasomotor symptoms affect up to 80% of

women and typically begin in perimenopause.5

Al-though most women will experience hot flushes for 6 months to 2 years, with frequency and severity im-proving with time, some women experience bother-some symptoms for many years. Hot flushes affect well-being and quality of life.6

Racial and ethnic background affects the likeli-hood of vasomotor symptoms. In the Study of Wom-en’s Health Across the Nation, compared with white women, Japanese and Chinese women were less likely and African-American women were more likely to report vasomotor symptoms.7Other factors

associ-ated with hot flushes in this and other studies include a high body mass index, smoking, and being less physically active.8 Hot flushes also are much more

likely in surgically menopausal women after bilateral oophorectomy than in naturally menopausal women. The physiologic mechanisms underlying hot flushes are incompletely understood. They seem to be the result of estrogen withdrawal, rather than simply low estrogen levels. A central event, probably initi-ated in the hypothalamus, drives an increased core body temperature, metabolic rate, and skin tempera-ture, resulting in peripheral vasodilation and sweat-ing, which lead to cooling. This central event may be

caused by noradrenergic, serotoninergic, or dopami-nergic activation. Although an LH surge often occurs at the time of a hot flush, it is not causative as vasomotor symptoms occur in women who have had their pituitary glands removed. In symptomatic post-menopausal women, hot flushes likely are triggered by small increases in core body temperature acting within a narrow thermoneutral zone.9 Exactly how

estrogen and alternative therapies play a role in modulating these events is unknown.

Treatment Options

Hormone Therapy

Systemic ET is the most effective treatment for vaso-motor symptoms and the only therapy currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for this indication. A Cochrane review of double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials of oral HT concluded that HT is highly effective in alleviating hot flushes and night sweats. Hot flush frequency was reduced 75%, and severity decreased as well.10 Withdrawals caused by side effects were

only marginally increased in the HT groups.

With greater awareness of HT risks, many low-dose HT products have been developed and ap-proved for symptom relief in postmenopausal women. A double-blind, randomized trial examined the efficacy and safety of low doses of conjugated estrogens combined with medroxyprogesterone ace-tate and found that lower doses relieved vasomotor symptoms and vaginal atrophy as effectively as stan-dard doses.11Doses of conjugated estrogens 0.45 and

0.3 mg/d, with and without concurrent medroxypro-gesterone acetate, significantly reduced the frequency and severity of hot flushes compared with placebo by the third week of treatment. No significant differences were observed between conjugated estrogens/me-droxyprogesterone acetate 0.625/2.5 and any of the lower-dosage conjugated estrogens/medroxyproges-terone acetate groups (0.45/1.5, 0.3/1.5), although low-dose conjugated estrogen without medroxypro-gesterone acetate (0.45, 0.3) was not quite as effective as standard-dose conjugated estrogens (0.625) or low-dose conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone ac-etate combinations. This may be because medroxy-progesterone acetate has an independent effect on hot flush reduction.12 Side effects, including breast pain

and vaginal bleeding, were more likely in women randomly assigned to HT compared with placebo and were generally more likely with higher-dose conju-gated estrogens (0.625) than with lower doses.

Low doses of transdermal estradiol (E2) also effectively treat hot flushes. In addition to standard doses of 0.1 and 0.05 mg/d, lower E2 patch doses of 0.025 and even 0.014 mg/d significantly reduce both the frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms compared with placebo.13 Regarding oral E2, in a

controlled trial of women with moderate to severe hot flushes, oral E2 0.5 and 1 mg/d were significantly better than placebo in reducing symptoms, whereas E2 0.25 mg/d was ineffective.14

Oral contraceptives are an alternate form of HT for the treatment of hot flushes in healthy, nonsmoking, perimenopausal women.

Contracep-Fig. 1.Health concerns of menopausal women. Illustration: John Yanson.

tion and management of irregular bleeding are additional benefits.

Although ET or combined estrogen and pro-gestin therapy may be contraindicated for some women, progestin therapy alone effectively treats hot flushes and may remain an option. Medroxy-progesterone acetate, available both orally and as a 3-month intramuscular injection, effectively treats vasomotor symptoms.12,15 In a 6-month study of

women with breast cancer, megestrol acetate (20 mg) resulted in a 75% or greater reduction in hot flushes in the majority of treated women, signifi-cantly greater than that seen with placebo,16

al-though progestins generally are not advised in women with a history of breast cancer.

Alternatives to Hormone Therapy

For women who are not candidates for HT or prefer alternatives, other options are available. Women ex-perience fewer hot flushes in a cooler environment,17

so symptomatic women should be encouraged to wear light, layered clothing, keep the thermostat low, and use portable fans at the desk and bedside. Be-cause an increased body mass index is a risk factor for hot flushes,7weight loss should be advised for

over-weight women as a healthy approach to reducing hot flushes. The incidence of thyroid disease increases as women age; therefore, thyroid function tests should be checked, especially if vasomotor symptoms are atypical or resistant to treatment.

Use of complementary and alternative medicine practices and products is increasing in the United States, with an estimated 76% of women aged 45– 65 years reporting use of an alternative therapy.18 One

popular complementary and alternative medicine therapy, acupuncture, has been shown to reduce vasomotor symptoms in several studies, although a traditional Chinese medicine approach may be no more effective than shallow or “sham” needling tech-niques.19 Phytoestrogens, plant-derived substances

with estrogenic properties, decrease hot flush severity and frequency, but symptom improvement is not superior to that seen with placebo treatment.20Black

cohosh is another popular alternative treatment for vasomotor symptoms, with efficacy likely similar to that of placebo.21Although often recommended,

vi-tamin E (800 international units/d) only minimally reduced hot flushes in a placebo-controlled, random-ized, crossover trial.22

Several drugs that alter central neurotransmitter pathways reduce vasomotor symptoms. Agents that decrease central noradrenergic tone, such as clonidine, decrease hot flushes, although the effect

size is not great. Selective serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors have become the mainstay of nonhormonal treatment of hot flushes, although none have been approved by the FDA for this purpose. In double-blind, randomized trials, both paroxetine and venlafaxine23 reduced hot flushes in symptomatic

menopausal women significantly more than placebo. Side effects of these agents may include headache, dry mouth, nausea, insomnia, and sexual dysfunction. Gabapentin, a ␥-aminobutyric acid analogue ap-proved for the treatment of seizures, has been shown to reduce hot flush frequency and severity signifi-cantly more than placebo in several double-blind, randomized trials.24 Side effects include dizziness,

drowsiness, and disorientation. Long-term studies of these agents for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms are not available.

Women who are principally bothered by night sweats and sleep disruption may benefit from a trial of sleep medication. The antihistamine, diphenhydra-mine hydrochloride, may serve as an inexpensive, over-the-counter sleep aid. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of perimenopausal and postmeno-pausal women, the prescription insomnia treatment eszopiclone significantly improved sleep and posi-tively effected mood, quality of life, next-day func-tioning, and menopause-related symptoms.25 When

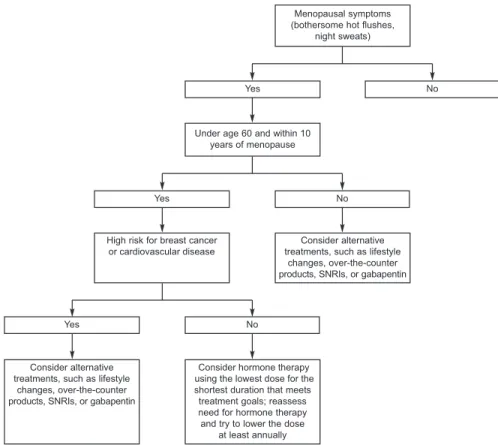

deciding between the available interventions for va-somotor symptoms, the safest options should be en-couraged first, such as lifestyle changes, proceeding to prescription treatments, as needed (Fig. 2). Patient preference, symptom severity, side effects, and the presence of other conditions, such as depression, will influence treatment choices. Box 1 provides a review of options for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms. Urogenital Atrophy

Vaginal dryness and associated symptoms are an important health concern affecting up to 75% of postmenopausal women.26Urogenital atrophy is

prin-cipally the result of estrogen deficiency and results in both vaginal and urinary symptoms, including vaginal dryness, pruritus, bleeding, dyspareunia, dysuria, uri-nary urgency, and recurrent uriuri-nary tract infections. On examination, changes may include petechiae, erythema, pallor, loss of elasticity and rugal folds, diminished secretions, and shortening and narrowing of the vagina. Vaginal pH increases, altering vaginal flora. In contrast to hot flushes, which improve with time, urogenital atrophy generally is progressive in the absence of treatment.

Treatment Options

Hormone Therapy

Systemic ET is very effective for the relief of vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and associated symptoms. When vasomotor symptoms are not present, low doses of estrogen applied vaginally are preferred to systemic ET because of minimal systemic absorption and increased safety. A Cochrane review of 19 trials with more than 4,000 women confirmed that vaginal estrogen preparations (including creams, rings, and tablets) were equally effective in treating the symp-toms of vaginal atrophy.27

Low doses of estrogen cream (0.5 g) are effective when used only one to three times weekly.28An E2

vaginal tablet (25 micrograms) inserted twice weekly may be less messy and easier to use than estrogen cream. An estrogen-containing sustained-release

vag-inal ring (7.5 micrograms/d) also is available, which is placed in the vagina every 3 months and slowly releases a low dose of E2.29

Studies of the vaginal tablets and ring have confirmed endometrial safety at 1 year, but studies of the long-term effects of low-dose vaginal ET on the endometrium are lacking. Women using vaginal ET should be told to report any vaginal bleeding, and this bleeding should be evaluated thoroughly. Progestins typically are not prescribed to women using only low-dose vaginal estrogen products.

Low-dose vaginal estrogens are minimally ab-sorbed systemically, so they remain an effective op-tion for treating urogenital atrophy in women for whom systemic ET may be contraindicated, including those with or at high risk for cardiovascular disease. Studies of the low-dose estrogen vaginal ring and tablet confirm a measurable increase in serum E2 and estrone levels, but these levels remain within or near the normal range for postmenopausal women.30

Lim-ited data are available on serum estrogen concentra-tions resulting from estrogen cream administration. Greater concern is present when considering vaginal ET for women with a history of breast cancer. The proven efficacy of estrogen agonist/antagonists (eg, tamoxifen, raloxifene) and aromatase inhibitors in the prevention and treatment of breast cancer confirms the importance of minimizing estrogen exposure in high-risk women. Although an observational study of women with a history of breast cancer found no significant difference in disease-free survival with vaginal estrogen use,31 the study was small and no

women were using aromatase inhibitors. Because aromatase inhibitors are effective by profoundly re-ducing circulating E2 levels, the small increases in serum E2 seen with low-dose vaginal ET, although still within the postmenopausal range, may be clini-cally significant in this particular group of women (Fig. 3).32

Incontinence

Although incontinence is a significant problem for aging women, the effect of estrogen deficiency re-mains unclear. Whereas some studies suggest im-provement in incontinence with HT, the WHI clinical trials reported that systemic ET and combined estro-gen and progestin therapy increase both stress and urge incontinence in postmenopausal women.33

Vaginal ET reduces irritative urinary symptoms, such as frequency and urgency, and has been dem-onstrated to reduce the likelihood of recurrent urinary tract infections in postmenopausal women.34

Box 1.Options for the Treatment of Vasomotor Symptoms

Life style changes

• Reducing body temperature • Maintaining a healthy weight • Smoking cessation

• Relaxation response techniques • Acupuncture Nonprescription medications* • Isoflavone supplements • Soy products • Black cohosh • Vitamin E

Nonhormonal prescription medications†

• Clonidine (0.1-mg weekly transdermal patch) Adverse effects: dry mouth, insomnia, drowsiness • Paroxetine (10 –20 mg/d, controlled release 12.5–25

mg/d)

Adverse effects: headache, nausea, insomnia, drowsiness, sexual dysfunction

• Venlafaxine (extended release 37.5–75 mg/d) Adverse effects: dry mouth, nausea, constipation, sleeplessness

• Gabapentin (300 mg/d to 300 mg three times daily) Adverse effects: somnolence, fatigue, dizziness, rash, palpitations, peripheral edema

Hormone therapy

• Estrogen therapy • Progestin alone†

• Combination estrogen-progestin therapy * Efficacy greater than placebo unproven.

†Not approved by U.S. Food and Drug Administration for

Alternatives to Hormone Therapy

Vaginal moisturizers, available without a prescription, are an effective nonhormonal alternative for reducing symptoms when urogenital atrophy is present.35They

improve and maintain vaginal moisture when used on a regular basis, so they should be applied at bedtime several times weekly, not just before sexual activity.

These products relieve symptoms of vaginal dryness even in women who are not sexually active. For women with dyspareunia, water-soluble lubricants should be used at the time of sexual activity, in addition to frequent use of vaginal moisturizers. Reg-ular sexual activity also is important in maintaining vaginal health in postmenopausal women. Women experiencing dyspareunia may elect to expand their repertoire to include nonintercourse sexual activities. Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis or low bone mass affects an estimated 44 million Americans, and 80% of those affected are women.36At the time of menopause, there is a phase

of rapid bone loss for 5–7 years, during which spine bone density may decrease by 15–30%. Bone loss then continues with aging, but at a much slower rate. Because therapy is most likely to benefit those at highest risk, it is important to review a woman’s risk factors for osteoporosis when making treatment deci-sions, and to consider bone mineral density (BMD) screening for high-risk women. Nonmodifiable risk factors include age, Asian or white race, family his-tory, history of a prior fracture, early menopause, and prior oophorectomy. Modifiable risk factors include a low body weight, decreased intake of calcium and

Symptoms of urogenital atrophy (vaginal dryness, dyspareunia)

History of breast cancer

Yes No

Vaginal lubricants and moisturizers; consider low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy

for persistent, bothersome symptoms after consultation

with patient’s oncologist

Low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy and/or vaginal lubricants and moisturizers

Fig. 3.Decision tree for patients with symptoms of urogen-ital atrophy, including vaginal dryness and dyspareunia. Shifren. Hormone Therapy. Obstet Gynecol 2010.

Menopausal symptoms (bothersome hot flushes,

night sweats)

Yes

Yes

No

Under age 60 and within 10 years of menopause

No

High risk for breast cancer or cardiovascular disease

Yes No

Consider alternative treatments, such as lifestyle

changes, over-the-counter products, SNRIs, or gabapentin

Consider hormone therapy using the lowest dose for the shortest duration that meets

treatment goals; reassess need for hormone therapy

and try to lower the dose at least annually

Consider alternative treatments, such as lifestyle

changes, over-the-counter products, SNRIs, or gabapentin

Fig. 2. Decision tree for patients with menopausal symptoms, in-cluding bothersome hot flushes and night sweats. SNRI, serotonin–nore-pinephrine reuptake inhibitor. Shifren. Hormone Therapy. Obstet Gynecol 2010.

vitamin D, smoking, and a sedentary lifestyle. Medi-cal conditions associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis include anovulation during the repro-ductive years (eg, caused by an eating disorder or excess exercise), hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroid-ism, chronic renal disease, and diseases necessitating systemic corticosteroid use.

Bone mineral density measurements may be used to diagnose osteoporosis, predict fracture risk, and identify women who would benefit from therapeutic interventions. Dual x-ray absorptiometry of the hip and spine is the primary technique for BMD assess-ment. Bone mineral density is expressed as a T score, which is the number of standard deviations from the mean for a young, healthy woman. A T score above ⫺1 is considered normal, a value between ⫺1 and ⫺2.5 denotes low bone mass, and a score below⫺2.5 indicates osteoporosis.37Evaluation of BMD by dual

x-ray absorptiometry is recommended for all women aged 65 years and older, and for younger postmeno-pausal women when there is concern based on clini-cal risk factors.38Osteoporosis may be assumed in any

postmenopausal woman with a low trauma fracture. Although there is a strong association between BMD and fracture risk, a woman’s age, overall health status, and risk for falls significantly influence her risk. FRAX, a very useful new online fracture risk assess-ment tool, provides the 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture for an individual woman (www. sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX).39 Based on cost-effectiveness

analyses,40pharmacologic treatment is recommended

when the 10-year risk of a hip fracture exceeds 3% or that of a major osteoporotic fracture exceeds 20%.

Treatment Options

Counseling women to alter modifiable risk factors is important for both the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Many women have diets deficient in calcium and vitamin D and will benefit from dietary changes and supplementation. Adequate calcium and vitamin D reduce bone loss and may even prevent fractures in older women. Postmenopausal women should receive 1,200 –1,500 mg of calcium and 800 – 1,000 international units of vitamin D daily. This may be achieved through diet or with vitamin and mineral supplements. Reducing the risk of osteoporosis is another of the many health benefits of smoking cessation and regular exercise. Strategies to prevent falls and reduce fall-related injuries should be advised for all women at risk for fracture. These may include installation of grab bars in showers, carpeting stairs, use of night lights, and wearing of padded clothing or hip protectors. The institution of pharmacologic

ther-apies is indicated for all women with osteoporosis, and for those with low bone mass and additional risk factors (see FRAX in the previous paragraph). Drug therapies for the prevention and treatment of osteo-porosis are principally antiresorptive drugs that re-duce bone loss and anabolic agents that stimulate new bone formation.

Hormone Therapy

Hormone therapy is effective at both preventing and treating osteoporosis. In observational studies, HT reduces osteoporosis-related fractures by approxi-mately 50% when started soon after menopause and continued long term, and significantly decreases frac-ture rates in women with established disease.41 The

WHI controlled trials confirmed a significant 33% reduction in hip fractures in healthy postmenopausal women receiving HT after an average follow-up of 5.6 years.421 Notably, hip fracture reduction was not

limited to women with osteoporosis, as in trials of other pharmacologic agents. Studies demonstrate that even very-low-dose ET (oral E2 0.25 mg/d, conju-gated estrogens 0.3 mg/d, transdermal E2 0.014 and 0.025 mg/d), combined with calcium and vitamin D, produce significant increases in BMD compared with placebo.43,44

Unfortunately, the increase in BMD and reduc-tion in fractures seen with HT does not persist after HT discontinuation. Data from the longitudinal co-hort National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment study confirm rapid bone loss after stopping HT, so that women who have discontinued HT more than 5 years previously have BMDs similar to those of never-users. In addition, current HT users in the National Osteo-porosis Risk Assessment study had a 40% reduction in hip fractures, which was lost by past users.45

There-fore, fracture risk and the potential need for an alternative therapy should be assessed when women discontinue HT.

Alternatives to Hormone Therapy

Bisphosphonates, including alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate, and zoledronic acid, specifically inhibit bone resorption and are highly effective for both osteoporosis prevention and treatment.46,47 Patients

should be instructed to take these drugs on an empty stomach with a large glass of water and to remain upright for at least 30 minutes. Once-weekly admin-istration of alendronate or risedronate and monthly use of ibandronate or risedronate are therapeutically equivalent to daily dosing and more convenient for patients. Annual administration of a single 15-minute intravenous infusion of zoledronic acid results in significant improvements in BMD and reductions of

both vertebral and hip fractures.48Side effects include

gastrointestinal distress and musculoskeletal pain. Esophageal ulceration is an uncommon risk of bisphosphonate use, and osteonecrosis of the jaw is a rare occurrence. Although concern has been raised regarding suppression of bone remodeling with long-term use of bisphosphonates, randomized, double-blind studies confirm continued safety and efficacy over 10 years of treatment.49

Selective estrogen receptor modulators are com-pounds that act as both estrogen agonists and antag-onists, depending on the tissue. Raloxifene is an estrogen agonist/antagonist approved for the preven-tion and treatment of osteoporosis.50Raloxifene

pre-vents vertebral fractures in women with low bone mass and osteoporosis, although it does not seem to reduce the risk of nonvertebral fractures, including hip fractures. Raloxifene also decreases the risk of invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women,51

so it is a particularly appropriate treatment option for women at increased risk for both fractures and breast cancer. Venous thromboembolic events are increased approximately twofold in raloxifene users, so it should not be used in women at high risk for these events.

Parathyroid hormone (recombinant human para-thyroid hormone 1–34, teriparatide), administered by daily subcutaneous injection, is a highly effective treatment for postmenopausal osteoporotic women at high risk for fractures. Unlike other approved agents that reduce bone resorption, parathyroid hormone is truly anabolic, resulting in dramatic increases in ver-tebral, femoral, and total body BMD with significant reductions in vertebral and nonvertebral fractures.52

Calcitonin administered by nasal spray or subcutane-ous injection is an approved treatment for established osteoporosis. Although not currently approved, deno-sumab, a monoclonal antibody to the receptor activa-tor of nuclear facactiva-tor-B ligand, decreases the risk of vertebral and hip fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis when given subcutaneously twice yearly for 36 months.53Box 2 provides a review of

options for osteoporosis prevention and treatment. Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease is a major health concern for postmenopausal women because it is the leading cause of death for women, accounting for approxi-mately 45% of mortality. Nonmodifiable risk factors include age and family history. Modifiable risk factors include smoking, obesity, and a sedentary lifestyle. Medical conditions associated with an increased risk of heart disease include diabetes, hypertension, and

hypercholesterolemia. Comprehensive care of midlife women must include a discussion about reducing modifiable risk factors and effectively treating associ-ated underlying medical conditions.

Treatment Options

Hormone Therapy

In the past, prevention of heart disease was thought to be a potential benefit of HT. Epidemiologic studies report an approximately 50% decrease in heart dis-ease in women who use HT.54This observed

reduc-tion in CHD was thought secondary to beneficial effects of HT on lipids55and direct actions on blood

Box 2.Options for Osteoporosis Prevention or Treatment

Bisphosphonate

Alendronate (35 or 70 mg/wk orally) Risedronate (35 mg/wk or 150 mg/mo orally) Ibandronate (150 mg/mo orally; 3 mg/every 3 mo intravenously)

Zoledronic Acid (5 mg/y intravenously) • Additional potential benefits: none

• Potential risks: esophageal ulcers, osteonecrosis of jaw (rare)

• Side effects: gastrointestinal distress, musculo-skeletal pain

Hormone Therapy

Estrogen or estrogen/progestin therapy

• Additional potential benefits: treatment of vaso-motor symptoms and urogenital atrophy

• Potential risks: breast cancer, gallbladder disease, venous thromboembolic events, cardiovascular disease, stroke

• Side effects: vaginal bleeding, breast tenderness

Estrogen Agonist/Antagonists

Raloxifene (60 mg/day orally)

• Additional potential benefits: reduced risk of breast cancer

• Potential risks: venous thromboembolic events • Side effects: vasomotor symptoms, leg cramps

Other

Calcitonin (200 international units/d intranasally; 100 international units subcutaneously or intramuscularly every other day)

• Additional potential benefits: none • Potential risks: none

• Side effects: rhinitis, back pain

Teriparatide (parathyroid hormone 1–34) (20 micro-grams/d subcutaneously)

• Additional potential benefits: none

• Potential risks: osteosarcoma after long-term use in rodents

vessels. Observational studies are prone to bias, how-ever, and women who used HT were generally at lower risk for heart disease than nonusers, a con-founding factor in observational studies known as “healthy user bias.”56

As described previously, in contrast to findings from observational studies, the WHI trial of estrogen plus progestin demonstrated an increased risk of CHD in postmenopausal women randomly assigned to combined estrogen and progestin therapy com-pared with placebo. The study had a planned dura-tion of 8.5 years but was stopped after 5.2 years when the global index statistic supported risks exceeding benefits. Risks (hazard ratio) were increased for CHD (1.3), breast cancer (1.3), stroke (1.4), and PE (2.1) and were decreased for hip fracture (0.7) and colorectal cancer (0.6).2 The absolute excess risk per 10,000

woman-years attributable to HT was small, with seven more CHD events, eight strokes, eight PEs, and eight breast cancers, and with six fewer colorectal cancers and five fewer hip fractures.

In the WHI trial of unopposed estrogen for women without a uterus, a small increased risk of stroke and venous thromboembolic events also was observed, but without an increased risk of CHD or breast cancer. Osteoporotic fractures were similarly reduced, without an effect on colorectal cancer.57 It

seems that the balance of risks and benefits is more favorable for women without a uterus receiving estro-gen-alone therapy. Whether this is because of adverse effects of adding progestin or underlying differences in women who have undergone hysterectomy is unknown.

A double-blind, randomized trial of combined estrogen and progestin therapy for the secondary prevention of CHD in women with preexisting dis-ease, the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study, also confirmed no role for combined estrogen and progestin therapy in the prevention of heart disease. Overall, there were no significant differences in cardiovascular outcomes between women treated with combined estrogen and progestin therapy or placebo,58although there was a significant time trend,

with more CHD events in women using combined estrogen and progestin therapy in year 1 and fewer in years 4 and 5.

The WHI trials examined only treatment with a fixed dose of conjugated equine estrogens and me-droxyprogesterone acetate. The effects of different doses, other oral estrogens, transdermal E2, other progestins, or cyclic administration of combined es-trogen and progestin therapy may be different, al-though information on other regimens is very limited.

As transdermal E2 does not result in an initial high hormone dose at the liver, avoiding the “first-pass hepatic effect,” cardiovascular outcomes may be dif-ferent. This was not confirmed in one study of trans-dermal HT in women with established CHD, which identified an increased risk of cardiac events (al-though not statistically significant) in women ran-domly assigned to transdermal HT compared with placebo.59

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the effects of transdermal E2, oral low-dose conjugated estrogens, and cyclic oral micronized pro-gesterone on carotid intimal medial thickness and accrual of coronary calcium in healthy, recently menopausal women is ongoing.60 Until data from

randomized controlled trials are available, the conser-vative approach is to assume that the risks of various HT regimens are similar.

Healthy user bias and other confounders likely explain the difference between the findings of obser-vational studies and the WHI clinical trials, but it is also possible that the timing of initiation of HT influences cardiovascular risk. In contrast to WHI, the majority of women in observational studies initiated HT at a younger age and within several years of menopause. As noted earlier, in a secondary analysis of data from the combined WHI trials, no increased risk of CHD was seen in women between the ages 50 and 59 years or in those within 10 years of meno-pause3(Table 1).

The “timing hypothesis” states that HT may have a beneficial effect on the heart if initiated early in the menopausal transition, when coronary arteries are relatively healthy, but a harmful effect if started in older women, when advanced atherosclerosis is present.61This hypothesis is supported by findings of

an ancillary study of the WHI estrogen-alone trial in which coronary-artery calcium scores were measured in a subset of women aged 50 –59 years at random-ization. After a mean of 7 years of treatment, calcified-plaque burden in the coronary arteries was lower in women randomly assigned to estrogen compared with placebo.62The implications of the timing

hypoth-esis are not that HT should be prescribed for the prevention of CHD in recently menopausal women, but rather that these women and their clinicians need not be overly concerned regarding cardiac risks when HT is used short term for bothersome vasomotor symptoms. Although stroke was increased with HT regardless of age or years since menopause in the WHI trials, the absolute excess risk of stroke in the younger women (aged 50 –59 years) was minimal,

approximately two additional cases per 10,000 per-son-years.3

In addition to heart disease and stroke, observa-tional studies and randomized clinical trials consis-tently demonstrate a twofold to threefold increased risk of venous thromboembolic events with HT use in postmenopausal women. Therefore, HT should not be used in women at high risk for venous thrombo-embolic events, including women with a prior PE, deep venous thrombosis, or known thrombophilia, and should be discontinued before periods of pro-longed immobilization. Of note, in observational studies, transdermal ET is not associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolic events.63

The effects of the estrogen agonist/antagonist raloxifene on coronary events was examined in an international, multicenter, randomized trial of ap-proximately 10,000 older postmenopausal women with CHD or multiple risk factors. As compared with placebo, raloxifene had no significant effect on coro-nary events, death from any cause, or total stroke, although risk of fatal stroke and venous thromboem-bolic events was increased.51 The risks of invasive

breast cancer and clinical vertebral fractures were significantly reduced.

Alternatives to Hormone Therapy

Currently, there is no role for HT in the prevention of heart disease in women. Assisting women in altering modifiable risk factors and identifying and treating diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia re-main the most effective measures to reduce the risk of CHD in postmenopausal women. According to the American Heart Association, a high percentage of women between the ages of 45 and 54 years have hypertension (30%), hypercholesterolemia (20%), or prediabetes (27%), smoke (20%), and are obese (40%). In a randomized study of interventions for diabetes prevention in high-risk adults, a lifestyle-modification

program with a goal of at least a 7% weight loss and at least 150 minutes of physical activity per week re-duced the incidence of diabetes by 58% and was more effective than metformin.64In the prospective

obser-vational Nurses’ Health Study, 82% of coronary events in the study cohort could be attributed to modifiable risk factors.65

Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women and is the second leading cause of cancer death.66The

lifetime risk of developing invasive breast cancer is 12%; therefore, any therapies that affect this risk will have a major effect on women’s health. Risk factors for breast cancer include age, early menarche, late menopause, family history, and prior breast disease. Oophorectomy and a term pregnancy before age 30 years are associated with reduced risk. Many of these risk factors are consistent with the hypothesis that prolonged estrogen exposure increases the risk of breast cancer.

Long-term use of HT is associated with an in-creased risk of breast cancer.67Observational studies

demonstrate a relative risk of approximately 1.3 with long-term HT use, generally defined as greater than 5 years. The WHI randomized controlled trial demon-strated a significant 26% increase in the risk of inva-sive breast cancer in women assigned to combined estrogen and progestin therapy after approximately 5 years of use.2Of note, the WHI trial of estrogen alone

in women with prior hysterectomy demonstrated no increased risk of breast cancer after an average of 7 years of estrogen use.57 Observational studies also

identify a reduced risk of breast cancer with ET compared with combined estrogen and progestin therapy,68although there remains an associated risk.

Estrogen-alone therapy was associated with a signifi-cantly increased risk of breast cancer after 15 years of

Table 1. Absolute Excess Risk of Coronary Heart Disease and Mortality93

Age (y) Years Since Menopause

Outcome 50–59 60–69 70–79 Less Than 10 10–19 20 or More

CHD ⫺2 ⫺1 ⫹19* ⫺6 ⫹4 ⫹17*

Total mortality ⫺10 ⫺4 ⫹16* ⫺7 ⫺1 ⫹14 Global index† ⫺4 ⫹15 ⫹43 ⫹5 ⫹20 ⫹23

CHD, coronary heart disease.

Absolute excess risk of CHD and mortality (cases per 10,000 patient-years) by age and years since menopause in the combined trials (estrogen plus progestin and estrogen alone) of the Women’s Health Initiative. Data from report published elsewhere.

*P⫽.03 compared with age 50 –59 years or less than 10 years since menopause.

†Global index is a composite outcome of CHD, stroke, pulmonary embolism, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer,

hip fracture, and mortality.

Reprinted from Martin KA, Manson JE. Approach to the patient with menopausal symptoms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:4568. Copyright 2008, The Endocrine Society.

current use in the Nurses’ Health Study69 and for

current users in the Million Women observational study of United Kingdom women.70

Although the primary goal of the WHI clinical trials was to evaluate the effects of HT on CHD risk, these trials also provided the first randomized clinical trial data on the association between HT and breast cancer risk. Interestingly, whereas observational stud-ies and WHI clinical trial data were at odds regarding CHD risk, findings regarding breast cancer were extremely consistent. An increased risk of breast cancer is seen after approximately 5 years of com-bined estrogen and progestin therapy use, with no increased risk seen in short-term or past users. These findings should be reassuring to women and their clinicians considering short-duration HT for bother-some hot flushes at the time of the menopausal transition.

Hormone therapy should not be prescribed to women with a history of breast cancer and should be used by women at high risk only after a careful assessment of potential risks and benefits. A random-ized trial of HT use in women with a history of breast cancer and bothersome vasomotor symptoms was terminated early, after 2 years of follow-up, when more new breast cancer events were diagnosed in women randomly assigned to HT.71

Treatment Options

Postmenopausal women at increased risk for breast cancer may elect chemoprevention with either ta-moxifen or raloxifene, estrogen agonist/antagonists approved for this indication. Tamoxifen reduces the risk of invasive breast cancer by approximately 50% in high-risk women, and a trial comparing both agents confirmed similar efficacy for raloxifene.72 Both

ta-moxifen and raloxifene increase the risk of venous thromboembolic events approximately twofold to threefold, similar to the increased risk seen with HT. Tamoxifen increases the risk of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer, whereas no endometrial effects are seen with raloxifene.

Screening mammography annually for women older than 50 years has been demonstrated to reduce breast cancer mortality. Monthly self– breast exami-nation also is recommended.

OTHER CANCERS

Because most cancers are detected after age 50 years, cancer screening and prevention strategies are impor-tant in the care of postmenopausal women.

Endometrial Cancer

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States. Fortunately, most cases are diagnosed at an early stage and cured by surgical management. Risk factors for endometrial cancer in-clude obesity, hypertension, diabetes, tamoxifen ther-apy, and unopposed estrogen use. The addition of at least 13 days of progestin monthly eliminates any in-creased risk, and concurrent progestin use is recom-mended for all women who have a uterus and use estrogen. No difference in the risk of endometrial cancer was seen with combined estrogen and progestin therapy use compared with placebo in WHI.73 Although HT

generally is contraindicated in women with a history of endometrial cancer, data support consideration of HT for highly symptomatic women with a history of early-stage endometrial cancer.74

Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer death in U.S. women. Risk factors include increasing age and family history; oral contraceptives are pro-tective in premenopausal women. No significant dif-ference in the risk of ovarian cancer was seen with combined estrogen and progestin therapy use com-pared with placebo in the WHI randomized trial,73

although a small increased risk was observed with HT use in a large prospective cohort study.75 Although

data are limited, HT does not seem to affect survival adversely in ovarian cancer survivors.

Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer is the third leading cause of cancer death for women, effectively prevented by removal of premalignant adenomas. Risk is increased with age, family history, and inflammatory bowel disease. For those at average risk, screening should begin at age 50 years. Colonoscopy every 10 years generally is recommended, with a shorter interval after the detection of polyps. The WHI clinical trial identified a reduced risk of colorectal cancer in women randomly assigned to combined estrogen and progestin therapy com-pared with placebo, although no effect on colorectal cancer risk was seen in the WHI trial of estrogen alone in women who had undergone hysterectomy. Given known risks of HT and effective screening options, HT should not be used for the prevention of colorectal cancer.

COGNITIVE FUNCTION

Although many women report cognitive changes at the time of the menopausal transition, a measurable

decline in cognitive abilities with menopause, distinct from those associated with aging, has not been clearly identified. Many studies have examined the effects of HT on a wide variety of cognitive tests, with variable results.76Overall, positive effects of HT on cognition

are more likely in women with vasomotor symptoms, probably because of the adverse effect of sleep dis-ruption on attention and memory, which improves with the treatment of hot flushes.

Regarding dementia, Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form, and the number of affected Americans is expected to double to more than 8 million by the year 2010. Women are at greater risk than men, and several small trials and observational studies suggested that HT use decreased the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.77The effect of HT on cognitive

function in women without dementia was studied in the WHI Memory Study, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of women aged 65 years or older enrolled in WHI. In contrast to the findings of observational studies, women randomly assigned to HT in the WHI Memory Study experi-enced a significant twofold increased risk of dementia, most commonly Alzheimer’s disease.78 In addition,

HT use was associated with an adverse effect on cognition. Compared with placebo-treated women, women in the HT group scored significantly lower on the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination.79

DEPRESSION AND MOOD

Depression is an important public health problem with a lifetime prevalence of approximately 18%. Women are twice as likely to be affected as men, and the perimenopausal transition seems to be a time of increased vulnerability. In the prospective Massachu-setts Women’s Health Study, over a period of approx-imately 2 years of observation, women who remained perimenopausal had a higher rate of depression than women who were premenopausal or postmenopausal, but the increase was largely explained by the pres-ence of menopausal symptoms. In a subsequent anal-ysis, E2 levels were inversely associated with depres-sion scores, but this finding was no longer significant after controlling for symptoms.80 Hot

flushes, night sweats, and trouble sleeping were highly related to depression, providing strong sup-port for the “domino” hypothesis that menopausal symptoms are the cause of increased depressed mood at this life stage.

Several controlled studies have demonstrated that HT is an effective treatment for depression in perimenopausal women.81,82 The majority of these

studies involved women with vasomotor symptoms,

so it is likely that the improvement of depressed mood was predominantly caused by resolution of bother-some hot flushes, night sweats, and sleep disruption with resulting improved quality of life.

Antidepressant medications are highly effective in the treatment of depression and, together with psychotherapy and counseling, should be the princi-pal therapeutic intervention for women with depres-sion. Women who present with bothersome vasomo-tor symptoms and associated disordered mood at the time of the menopausal transition may elect a trial of HT for symptom relief. Although HT should not be considered treatment for depression, improvement of mood symptoms concurrent with resolution of hot flushes and disrupted sleep is likely.

HORMONE THERAPY OPTIONS

Hormone therapy remains the most effective treat-ment for vasomotor symptoms and the only currently FDA-approved option. For a healthy woman with bothersome hot flushes, especially if she is younger than 60 years and within 10 years of menopause, HT remains a reasonable option. Women should be advised that HT should be used at the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration consistent with treat-ment goals.76,83The continued need for HT should be

assessed at least annually.

Many HT options are available, including a wide range of estrogens, progestins, doses, and modes of administration. Combination estrogen and progestin therapy is recommended for all women with a uterus to prevent adverse endometrial effects. Treatment may be cyclic, with estrogen daily and progestin for at least 13 days of each month, or in a continuous-combined fashion with estrogen and a lower dose of progestin daily. Continuous-combined regimens gen-erally result in amenorrhea, although breakthrough bleeding may be bothersome, especially in the first year of use. Currently available low-dose combina-tion therapies result in a lower incidence of bleeding and other symptoms, including breast tenderness.84

Women using low doses of oral or transdermal estro-gens may elect intermittent administration of proges-tin, eg, 14 days every 3– 4 months,85 although these

are not approved regimens. Approved for contracep-tion in premenopausal women, a progestin-containing intrauterine device has been shown to provide endo-metrial protection in estrogen-treated menopausal women.86 Increased endometrial surveillance is

ad-vised with these approaches, informing women to report any bleeding episode unrelated to progestin use, and assessing the endometrium by ultrasonogra-phy or biopsy should bleeding occur.

Transdermal administration of E2 with a patch, gel, or spray may be preferred by some women. Avoiding the first-pass hepatic effect results in the absence of changes in lipids, clotting factors, and various binding globulins seen with oral administra-tion of estrogens. This may have theoretical benefits for women with hypothyroidism on replacement or those with low libido on oral estrogens.87In contrast

to oral administration, transdermal E2 does not seem to increase the risk of venous thromboembolic events or gallbladder disease, although it remains contrain-dicated in women with active liver or gallbladder disease or at high risk for venous thromboembolic events.

Popularized in the lay press and by film stars, many women are interested in using “bioidentical hormones” for treatment of their menopausal symp-toms.Bioidenticalis not a medical term but generally refers to hormones structurally identical to “natural” hormones made by the ovary, E2 and progesterone. Fortunately, many bioidentical HT products are gov-ernment approved with proven efficacy and known safety profiles. Both oral and transdermal approved E2 products are available by prescription in a wide range of doses. An approved oral formulation of micronized progesterone also is available. It may cause drowsiness, so it should be taken at bedtime. Although of unknown clinical significance, micron-ized progesterone results in a more favorable lipid profile than synthetic progestins.55The North

Amer-ican Menopause Society provides a table summ-arizing all currently approved HT products at http://www.menopause.org/htcharts.pdf.

There is absolutely no known benefit and poten-tially significant increased risk to the use of custom-compounded bioidentical HT formulations, prepara-tions that are mixed and packaged by a pharmacist, “custom made” for a patient based on a physician’s specifications. Purity, bioavailability, and dose consis-tency are uncertain, and safety and efficacy are un-tested. Safety information typically is not provided to patients when they fill these prescriptions. There also is no evidence to support the use of any form of hormone measurement to adjust HT doses, although a serum E2 level may be useful to confirm adequate systemic absorption in a woman with persistent vaso-motor symptoms despite standard doses of an FDA-approved HT regimen. No useful information is provided by salivary hormone levels. The lowest dose of estrogen that treats a woman’s symptoms, with adequate progestin to protect the endometrium, should be prescribed.

DISCONTINUING HORMONE THERAPY Vasomotor symptoms seem to be the result of estro-gen withdrawal, rather than simply low estroestro-gen levels. Therefore, if cessation of HT is desired, doses should be reduced slowly over several months, be-cause abruptly stopping treatment may result in a return of disruptive vasomotor symptoms. This rec-ommendation is based on clinical experience, be-cause limited trial data are available. One observa-tional study identified no difference in successful quitting between tapering HT compared with stop-ping abruptly,88whereas another found that tapering

was significantly associated with lower menopausal symptom scores after discontinuation.89 Because

breast cancer risk increases after approximately 5 years of combined estrogen and progestin therapy use and cardiovascular disease risk increases with increas-ing age, women should be encouraged to decrease their HT dose at least annually to be certain they are using the lowest effective dose and, hopefully, in-crease the likelihood of successful discontinuation. Some women will continue to experience severe vasomotor symptoms many years beyond meno-pause, despite frequent attempts to slowly discontinue therapy. A careful assessment of individual risks and benefits is required in these cases, and some women may elect long-term use.

EARLY MENOPAUSE AND HORMONE THERAPY USE

The findings of the majority of clinical trials on the benefits and risks of menopausal HT are relevant to women aged 50 years and older. For women experi-encing an early menopause, especially before the age of 45 years, the benefits of using HT until the average age of natural menopause likely will significantly outweigh risks. The large body of evidence on the overall safety of oral contraceptives in younger women should be reassuring for those experiencing an early menopause, especially given the much lower estrogen and progestin doses provided by HT formu-lations. Not only are treatment of vasomotor symp-toms and vaginal atrophy and maintenance of BMD important for younger women, but early menopause seems to be associated with an increased risk of CHD. In the prospective Nurses’ Health Study, involv-ing approximately 29,000 women over 24 years of follow-up, compared with ovarian conservation, bilat-eral oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease was associated with a decreased risk of breast and ovarian cancer, but an increased risk of CHD, lung cancer, and all-cause mortality.90

Specifi-cally, those with oophorectomy before age 50 years who never used ET had a higher CHD risk. In another observational cohort study, women who un-derwent bilateral oophorectomy before age 45 years experienced increased cardiovascular mortality, which was not seen in women treated with estrogen.91

An increased risk of cognitive impairment or demen-tia also has been observed in women who underwent oophorectomy before the onset of menopause.92

CONCLUSION

There are many options available to address the quality of life and health concerns of menopausal women. The primary indication for HT is the allevi-ation of hot flushes and associated symptoms. Hor-mone therapy remains the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms and currently the only FDA-approved option. Benefits generally outweigh risks for healthy women with bothersome hot flushes at the time of the menopausal transition. Hormone therapy prevents and treats osteoporosis but rarely should be used solely for this indication, if other effective op-tions are well tolerated. If estrogen treatment is elected for isolated vaginal symptoms, low-dose local ET is advised.

Women should be fully informed of the goal of using the lowest effective estrogen dose for the short-est duration necessary, because risks increase with increasing age and duration of use. Contraindications to HT use include breast or endometrial cancer, cardiovascular disease, thromboembolic disorders, and active liver or gallbladder disease. Alternatives to HT should be advised for women with or at increased risk for these disorders. Women must be informed of the potential benefits and risks of all therapeutic options, and care should be individualized, based on a woman’s medical history, needs, and preferences. REFERENCES

1. Wilson RA. Feminine forever. New York (NY): M. Evans; 1966.

2. Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooper-berg C, Stefanick ML, et al; Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized con-trolled trial. JAMA 2002;288:321–33.

3. Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, Wu L, Barad D, Barnabei VM, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since meno-pause. JAMA 2007;297:1465–77.

4. Schiff I, Regestein Q, Tulchinsky D, Ryan KJ. Effects of estrogens on sleep and psychological state of hypogonadal women. JAMA 1979;242:2405–7.

5. Woods N, Mitchell E. Symptoms during the perimenopause: prevalence, severity, trajectory, and significance in women’s lives. Am J Med 2005;118:14S–24S.

6. Oldenhave A, Jaszmann LJ, Haspels AA, Everaerd WT. Impact of climacteric on well-being: a survey based on 5213 women 39 to 60 years old. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993;168: 772– 80.

7. Gold EB, Sternfeld B, Kelsey JL, Brown C, Mouton C, Reame N, et al. Relation of demographic and lifestyle factors to symptoms in a multi-racial/ethnic population of women 40 –55 years of age. Am J Epidemiol 2000;152:463–73.

8. Whiteman MK, Staropoli CA, Langenberg PW, McCarter RJ, Kjerulff KH, Flaws JA. Smoking, body mass, and hot flashes in midlife women. Obstet Gynecol 2003;101:264 –72.

9. Freedman RR, Subramanian M. Effects of symptomatic status and the menstrual cycle on hot flash-related thermoregulatory parameters. Menopause 2005;12:156 –9.

10. Maclennan A, Broadbent J, Lester S, Moore V. Oral oestrogen and combined oestrogen/progestogen therapy versus placebo for hot flushes. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004, Issue 4. Art. No. CD002978. DOI: 10.1002/ 14651858.CD002978.pub2.

11. Utian WH, Shoupe D, Bachmann G, Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH. Relief of vasomotor symptoms and vaginal atrophy with lower doses of conjugated equine estrogens and medroxyprogester-one acetate. Fertil Steril 2001;75:1065–79.

12. Schiff I, Tulchinsky D, Cramer D, Ryan KJ. Oral medroxy-progesterone in the treatment of postmenopausal symptoms. JAMA 1980;244:1443–5.

13. Bachmann GA, Schaefers M, Uddin A, Utian WH. Lowest effective transdermal 17-estradiol dose for relief of hot flushes in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:771–9.

14. Notelovitz M, Lenihan JP, McDermott M, Kerber IJ, Nanavati N, Arce J. Initial 17-estradiol dose for treating vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95:726 –31.

15. Loprinzi CL, Levitt R, Barton D, Sloan JA, Dakhil SR, Nikcevich DA, et al. Phase III comparison of depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate to venlafaxine for managing hot flashes: North Central Cancer Treatment Group Trial N99C7. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:1409 –14.

16. Goodwin JW, Green SJ, Moinpour CM, Bearden JD III, Giguere JK, Jiang CS, et al. Phase III randomized placebo-controlled trial of two doses of megestrol acetate as treatment for menopausal symptoms in women with breast cancer: Southwest Oncology Group Study 9626. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:1650 – 6.

17. Kronenberg F, Barnard RM. Modulation of menopausal hot flashes by ambient temperature. J Therm Biol 1992;17:43–9. 18. Newton KM, Buist DS, Keenan NL, Anderson LA, LaCroix

AZ. Use of alternative therapies for menopause symptoms: results of a population-based survey. Obstet Gynecol 2002; 100:18 –25.

19. Avis NE, Legault C, Coeytaux RR, Pian-Smith M, Shifren JL, Chen W, et al. A randomized, controlled pilot study of acupuncture treatment for menopausal hot flashes. Menopause 2008;15:1070 – 8.

20. Krebs EE, Ensrud KE, MacDonald R, Wilt TJ. Phytoestrogens for treatment of menopausal symptoms: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104:824 –36.

21. Newton KM, Reed SD, LaCroix AZ, Grothaus LC, Ehrlich K, Guiltinan J. Treatment of vasomotor symptoms of menopause with black cohosh, multibotanicals, soy, hormone therapy, or placebo: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2006;145: 869 –79.

22. Barton DL, Loprinzi CL, Quella SK, Sloan JA, Veeder MH, Egner JR, et al. Prospective evaluation of vitamin E for hot flashes in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 1998;16: 495–500.

23. Loprinzi CL, Kugler JW, Sloan JA, Mailliard JA, LaVasseur BI, Barton DL, et al. Venlafaxine in management of hot flashes in survivors of breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000;356:2059 – 63.

24. Guttuso T Jr, Kurlan R, McDermott MP, Kieburtz K. Gabap-entin’s effects on hot flashes in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2003;101: 337– 45.

25. Soares CN, Joffe H, Rubens R, Caron J, Roth T, Cohen L. Eszopiclone in patients with insomnia during perimenopause and early postmenopause: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:1402–10.

26. North American Menopause Society. The role of local vaginal estrogen for treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: 2007 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2007;14:357– 69.

27. Suckling J, Kennedy R, Lethaby A, Roberts H. Local oestrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 4. Art No. CD001500. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001500.pub2. 28. Handa VL, Bachus KE, Johnston WW, Robboy SJ, Hammond

CB. Vaginal administration of low-dose conjugated estrogens: systemic absorption and effects on the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol 1994;84:215– 8.

29. Henriksson L, Stjernquist M, Boquist L, Cedergren I, Selinus I. A one-year multicenter study of efficacy and safety of a continuous, low-dose, estradiol-releasing vaginal ring (Estring) in postmenopausal women with symptoms and signs of uro-genital aging. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;174:85–92. 30. Weisberg E, Ayton R, Darling G, Farrell E, Murkies A, O’Neill

S, et al. Endometrial and vaginal effects of low-dose estradiol delivered by vaginal ring or vaginal tablet. Climacteric 2005; 8:83–92.

31. Dew JE, Wren BG, Eden JA. Tamoxifen, hormone receptors and hormone replacement therapy in women previously treated for breast cancer: a cohort study. Climacteric 2002;5: 151–5.

32. Kendall A, Dowsett M, Folkerd E, Smith I. Caution: vaginal estradiol appears to be contraindicated in postmenopausal women on adjuvant aromatase inhibitors. Ann Oncol 2006;17: 584 –7.

33. Hendrix SL, Cochrane BB, Nygaard IE, Handa VL, Barnabei VM, Iglesia C, et al. Effects of estrogen with and without progestin on urinary incontinence. JAMA 2005;293:935– 48. 34. Eriksen B. A randomized, open, parallel-group study on the

preventive effect of an estradiol-releasing vaginal ring (Estring) on recurrent urinary tract infections in postmenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;180:1072–9.

35. Nachtigall LE. Comparative study: Replens versus local estro-gen in menopausal women. Fertil Steril 1994;61:178 – 80. 36. National Osteoporosis Foundation. Disease statistics. Fast facts.

2004. Available at: www.nof.org. Retrieved January 22, 2010. 37. World Health Organization. Assessment of osteoporosis at the primary health care level: summary report of a WHO Scien-tific Group. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. 38. National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s guide to

pre-vention and treatment of osteoporosis. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 2008.

39. Watts N, Ettinger B, LeBoff M. Perspective: FRAX facts. J Bone Min Res 2009;24:975–9.

40. Tosteson AN, Melton LJ III, Dawson-Hughes B, Baim S, Favus MJ, Khosla S, et al; National Osteoporosis Foundation Guide Committee. Cost-effective osteoporosis treatment thresholds: the United States perspective. Osteoporosis Int 2008;19: 437– 47.

41. Cauley JA, Zmuda JM, Ensrud KE, Bauer DC, Ettinger B; Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Timing of estrogen replacement therapy for optimal osteoporosis preven-tion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:5700 –5.

42. Cauley JA, Robbins J, Chen Z, Cummings SR, Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, et al; Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Effects of estrogen plus progestin on risk of fracture and bone mineral density. JAMA 2003;290:1729 –38.

43. Prestwood KM, Kenny AM, Kleppinger A, Kulldorff M. Ultralow-dose micronized 17-estradiol and bone density and bone metabolism in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290:1042– 8.

44. Ettinger B, Ensrud KE, Wallace R, Johnson KC, Cummings SR, Yankov V, et al. Effects of ultralow-dose transdermal estradiol on bone mineral density: a randomized clinical trial. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104:443–51.

45. Yates J, Barrett-Connor E, Barlas S, Chen Y-T, Miller P, Siris E. Rapid loss of hip fracture protection after estrogen cessation: evidence from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104:440 – 6.

46. Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, Applegate WB, Barrett-Connor E, Musliner TA, et al. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial. JAMA 1998;280:2077– 82.

47. Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK, McKeever CD, Hangartner T, Keller M, et al. Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Vertebral Efficacy With Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. JAMA 1999;282:1344 –52.

48. Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R, Reid IR, Boonen S, Cauley JA, et al; HORIZON Pivotal Fracture Trial. Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1809 –22.

49. Bone HG, Hosking D, Devogelaer JP, Tucci JR, Emkey RD, Tonino RP, et al; Alendronate Phase III Osteoporosis Treat-ment Study Group. Ten years’ experience with alendronate for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med 2004; 350:1189 –99.

50. Ettinger B, Black DM, Mitlak BH, Knickerbocker RK, Nick-elsen T, Genant HK, et al. Reduction of vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis treated with raloxifene: results from a 3-year randomized clinical trial. Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) Inves-tigators. JAMA 1999;282:637– 45.

51. Barrett-Connor E, Mosca L, Collins P, Geiger MJ, Grady D, Kornitzer M, et al; Raloxifene Use for the Heart (RUTH) Trial Investigators. Effects of raloxifene on cardiovascular events and breast cancer in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med 2006;355:125–37.

52. Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, Prince R, Gaich GA, Reginster JY, et al. Effect of parathyroid hormone (1–34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1434 – 41. 53. Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, Siris ES, Eastell R,

Reid IR, et al; FREEDOM Trial. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2009;361:756 – 65.