Title Evaluative comments in narratives of Cantonese speakingchildren

Other

Contributor(s) University of Hong Kong

Author(s) Leung, Wing-fai; 梁詠暉

Citation

Issued Date 2001

URL http://hdl.handle.net/10722/56280

Evaluative comments in narratives of

Cantonese Speaking children

Leung Wing Fai

A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Sciences (Speech and Hearing Sciences), The University of Hong Kong, May, 4,2001

Abstract

This study investigated the use of evaluative devices in narratives of Cantonese speaking children. The evaluative devices include: a) frames of mind, b) negative qualifiers, c) hedges, d) character's speech, and e) causal connectors. A 24-pictured story-book was used to elicit narrative. Four groups of Cantonese- speaking subjects were recruited: five-, seven-, nine-year-old children and University undergraduate students. A quantitative comparison revealed that (i) there is significant increase in the use of frames of mind, negative qualifiers and causal connectors across age. (ii) Pattern of evaluative devices used by five- year-old children is similar to that of the seven-year-old children. While adults and nine-year-old children form unique pattern in the use of different evaluative devices. These findings are discussed with cognitive, linguistic and pragmatic achievements.

Introduction Background information

Traditionally, most researches on language development have been focused on syntactic, semantic and phonological development. However, recently, there is an increased interest in studying narrative development in children. This increased in interest may be motivated by the awareness of the importance of narrative skills to children's language, social as well as cognitive development. Through narrative, children will learn to organize the complex relationship within the world, make sense out of them and express their ideas (Heath, 1986). Narrative is also a cognitive instrument which could be used to construct reality and form identity (Nicolopoulou, 1997). Apart from these, narrative also forms a bridge between oral and written language skills, and is considered to be a prerequisite for written language development (Hedberg & Westby, 1993).

In the view of clinicians and researchers, studying narrative provide means to understand language and conceptual development beyond the word and sentence level (Hedberg & Westby, 1993). Children have to work on a local level and a global level in telling stories (Hedberg & Westby, 1993). The local level concerns the linguistic level of story, while the global level concerns the general structural organization and conceptual level of story (Hedberg & Westby, 1993). Therefore, narrative production would draws on children's linguistic, cognitive and social knowledge. Children who have limited linguistic, cognitive and social skills will probably have difficulty in producing "good" narrative as well

In view of the importance of narrative competence for development of language, social as well as cognitive skills in children, there have been increasing interest to study its development in the past decades. Different approaches have been developed to analyze and

study narrative skills in children.

Hedberg & Westby (1993) have proposed 3 primary and 4 secondary systems for analyzing narrative. Primary system includes narrative level analysis, story grammar analysis and cohesive tie and cohesion analysis (Hedberg & Westby, 1993). Secondary analysis would include Karmiloff-Smith analysis of local cohesive link use, comprehension question, planning behavior analysis and high-point analysis (Hedberg & Westby, 1993).

High Point analysis

High point analysis was employed here to study narrative production of Cantonese speaking children. It was an analysis system developed by Labov and Waletzky (1967). It identified narrative as "sequence of two or more narrative clauses separated by one or more temporal juncture" (Labov, 1972). In a study done by Labov and Waletzky (1967), they analyzed oral narratives of personal experiences produced by adolescence and adults, aiming to "isolate the invariant structural units" in variety of personal narratives (Labov & Waletzky,

1967).

The authors started with distinction between two functions of narratives, which is evaluative and referential (Labov & Waletzky, 1967). Referential function of narrative refers to summarizing of events in temporal sequence. However, it is unnatural to produce narrative by simply reporting events in sequence. Speaker should also inform the listener about the importance and point of narrative through evaluation. Evaluative function then serves to gives point to the narrative and places the narrator in their best position.

Labov (1972) identified 6 elements that should be included in a well formed narrative, which are: abstract, orientation, complicating action, evaluation, resolution and coda.

beginning of the narrative.

- Orientation consisted of clauses that orient listener to time, person, place and the situation.

- Complicating action consisted of clauses that lead to the high point of the narrative. - Evaluation consisted of clauses that give the point of the narrative.

- Resolution refers to events that follow the high point.

- Coda is the ending of the narrative, it is also use to bridge the gap between the present and the time at the end of the narrative.

Evaluative devices

Evaluation is defined as "part of narrative reveals the attitude of the narrator towards the narrative by emphasizing the relative importance of some narrative units as compared to others" (Labov & Waletzky, 1967). It can be achieved through a variety of means. In Labov (1972)'s later research, he identified several ways to achieve evaluative function of narrative. Speaker could make use of (1) external evaluation - by stopping at a point and tell the listener the point of narrative, (2) embedded evaluation - by quoting the feelings or thoughts as occurring to speaker himself, (3) evaluative action -by telling what a person did, and (4) suspension of action - by expression of emotions (Labov, 1972). Labov (1972) noted that evaluation could be distributed throughout the narrative but will usually concentrated at the high point. Apart from the external mechanism mentioned, Labov (1972) also identified syntactic devices in clauses that could carry out the evaluative function. Labov (1972) points out that narrative syntax involves simplest grammatical pattern, and departure from the basic syntax would have a effect of evaluation. Therefore the author identified totally four types of devices that could carry out the evaluative function, they are intensifies comparators,

correlatives and explications. They differ in the degree of syntactic complexity, and would undergo development from preadolescence to adult.

The pioneer study carried out by Labov (1972) forms the stepping stone for later study in the use of evaluative devices. In investigating the use of evaluative devices by children, different authors identified different types of evaluative devices. However, despite of the different labels and criteria used to categorize evaluative devices, the basic concept underlying identification of evaluative devices were the same. In a study carried by Peterson and McCabe (1983), 21 types of evaluative devices were identified, they are onomatopoeia, stressors, elongators, exclamations and laughs, repetitions, compulsion words, smiles and metaphors, gratuitous terms, attention-getters, words per se, exaggeration and fantasy, negatives, intentions or desires, hypotheses or inferences, results of hi point action, causal explanations, objective judgements, subjective judgements, descriptions of Internal emotional states, Facts per se and tangential information (Peterson & McCabe, 1983). After that Bamberg and Damrad-Frye (1991) identified 5 types of evaluative devices in their study by taking and reformulating categories of evaluative devices developed by Peterson and McCabe (1983). They assume that these 5 types of evaluative devices could adequately reflect evaluation of adult and children. The evaluative devices are: frames of mind, hedges, causal connectors, character's speech and negative qualifiers.

Although it seems that orientation, complicating action and resolution are more essential and important to tell narrative. However, they could only fulfill referential function of narrative, evaluation section is needed to fulfill the evaluative function of narrative.

Evaluation assume an important function that it give points to the narrative, maintain listener's interest and place the narrator in their favorite position when narrating. Apart from

that, evaluation has an effect on narrative structure. It serves to distinguish between complicating action from resolution by emphasizing the point where complicating action has reached the maximum (Labov, 1972). Without evaluation, it will be hard for the listener to distinguish between complicating action and resolution.

In the view of all these importance of evaluation to production of narrative, children must learn to use them in the course of development to produce socially acceptable narrative. It is expected that the use of evaluative devices will increase with age when there is development in cognitive, linguistic, social and pragmatic skills.

Research on use of evaluative devices by children

As mentioned previously, there are several studies carried out concerning development in the use of different evaluative devices. In a study carried out by Peterson and McCabe (1983) concerning narrative development in children, they investigated the use of 21 types of evaluative devices by children of different ages. Among all types of evaluative devices, gratuitous terms, stressorsk, negative statements, compulsion words, and causal explanations are heavily used (Peterson & McCabe, 1983). However, exaggeration and fantasy, words per se, smiles and metaphors, objective judgements, or tangential information would be rarely used by children.

This study showed that there was no difference in the overall amount of evaluation used across age, but older children would tend to use larger variety of evaluators. They also found that children would concentrate the use of evaluation at the high-point of their narrative, that helps to indicate relative importance of events.

There is another study carried out by Bamberg and Damrad-Frye (1991) investigating the ability of children, age 5 to age 9, to provide evaluative comments in story-book elicited

narratives. Results showed that adult used significantly more "frames of mind" and "hedges" than children. It was also found that nine-years old children and adult would used significantly more "frames of mind" than the other four types of evaluative devices, while five years old children would used each type of evaluative devices equally often. This study then performed a detailed analysis on the use of "frames of mind", and it focused on where this particular type of evaluative device was used. It showed that when age increases, this evaluative device would be used to signal hierarchical organization of story events. Rationale for investigating the use of evaluative devices

Investigating the use of evaluative devices by children could facilitate our understanding concerning children's conception of the world and other people. Moreover, ability to use different types of evaluative devices could indicate development in narrative competencies across age, i.e. how children develop in their ability to use narrative to communicate effectively. When use of evaluative devices increases, narrative will be less descriptive, richer in content and more appropriate to cultural norms. Furthermore, their narrative will be more attractive to listener and therefore could hold listener's attention. All these indicate an advance in narrative skills.

In the view of the importance of evaluation to production of narrative and their implication to development of narrative competencies, it is worthwhile to study their use by children. Recently, there was no research found on use of evaluative devices by Cantonese speaking children, cultural difference is likely to have effect on the use of evaluative device. As a result, this study is carried out to investigate use of evaluative devices in Cantonese speaking children's narrative.

Damrad-Frye (1991) categories of linguistic devices. The five types of evaluative devices included: Frames of mind, hedges, negative qualifiers, character's speech and causal connectors. However, instead of looking at where the evaluative devices were place in the narrative, this study will look at the age difference in the quantity and pattern of evaluative devices used. Quantitative analysis is preferred, as it is a more objective measure for the use of evaluative devices at different age.

Aims of this study

To summarize, the aims of this study are to find out difference in the amount and pattern of evaluative devices used at different age.

Methodology Subjects

Three groups (5, 7 and 9 years old) of 10 (5 males and 5 females) Cantonese speaking children participated in the study. They were randomly selected from 1 kindergarten and 1 primary school. All the children were reported as having normal hearing, speech and language abilities.

In addition, a group of 10 adults (5 males and 5 females), who are all university students aged from 19 to 24 were chosen as control group.

Material

A wordless picture story book "Frog, where are you?" (Mayer, 1969) was used in this study to elicit narratives form children. The picture book contain 24 pictures, which is about a boy who have lost his frog try to find his pet frog with his dog. During the search, they encounter some difficulties.

Procedure

Each subject was sat opposite to the experimenter in a quiet room. The experimenter chatted with the subject in the beginning to build up rapport. After that, the subject was asked to read the story-book once and tell the story.

The experimenter introduced the task by saying "I have got a story book about a frog, a boy and a dog. Please read the story once first and tell what the story is about"

Time limit was not imposed. Prompts like "what did it have?" r Wt3lF3f ? j , "please

tell me" r BWWMl J and "and then" rM£Wj was used when the child have no response. Neutral reinforcement like "You have tried your best" r 0|j\tJffiWf j or "the story is

good" r l#f#$?$?|^DiWi j was used to reinforce the child when he/ she tried his/ her best to tell

the story. No time limit was imposed. Coding and analysis

All narratives were recorded and transcribed. After that each story was segmented into clauses using procedure described by Wong (1992).

Evaluative devices Applying the definition of Bamberg & Damrad-Frye (1991), the five types of evaluative devices are (1) frames of mind, (2) character speech, (3) distancing devices, (4) negative statements and (5) causal connectors. Below are definitions of different types of evaluative devices:

1) Frames of mind: This category include lexical items for reference to emotional states (e.g. W "angry", H;[> "happy"), mental states or activities (e.g. H "think", M "hope"). Emotional verbs is also included (e.g.

#"frightened").

2) Character speech: Direct and indirect speech of the characters are included in this category. For example: Direct speech ff S I S : W&t "The frog said " good"", Indirect speech: /^MW^kWhb "The boy told the dog to be careful"

3) Negative qualifiers: Direction negation is included like: fj "no", Pg "not"

4) Hedges: It consists of lexical devices that suspect the truthfulness of the proposition, for example: i^fyX "seems to be". It is considered as "distancing devices" by Bamberg and Damrad-Frye (1991).

5) Causal Connectors: This category consists of interclausal connectors like: H ^ (because), jS/fJ^ (so) and i£(to).

Number of each evaluative device was counted, and proportion of evaluative devices used across age was then calculated by dividing total number of each evaluative device by total number of clauses.

Reliability

Ten percent of the stories were transcribed and coded by another scorer, point by point agreement was 97%. Inter-rater reliability was calculated by mean number of agreement over the number of disagreements plus agreements. The inter-rater reliability range from 81% to 90%. Disagreement was resolved after subsequent discussion.

Results Story length

Story length was indicated by total number of clauses produced. The mean number of clauses was indicated in the table below:

Table 1: Mean number of clauses produced in different age group. Age 5 7 9 23

Mean number of clauses

42.30 59.10 67.50 63.40

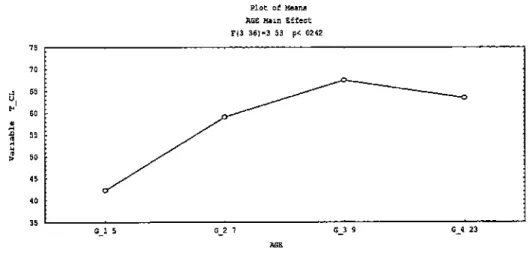

One way ANOVA was carried out to examine the difference in total number of clause produced across age. Results indicated that there is significant difference in the number of clauses produced across age F(3,36)=3.53, p<0.02. Figure 1 shows the mean number of clauses produced in different age groups.

Plot of Means AGE M a m Effect F(3 36)=3 53 p< 0242

G 1 5 G_2 7 G_3 9 G_4 23 AGE

Figure 1: Mean number of clauses produced in different age group Number of evaluative devices used

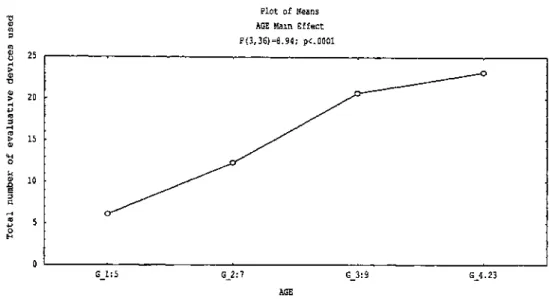

Proportion as well as total number of evaluative devices was subjected to a Kruskal-Wallis one way ANOVA. Results showed that there is significant increase in the use

of evaluative devices across age (EN20.52, d.f. = 3, p<0.05). Mann-Whitney U test was then carried out to compare difference between groups. Results reveal that significant difference lies between 5 and 7 years old

70 | 65 60 I 55 I 50 45 40

(U-20.50, p<0.05). Means of evaluative devices used at different age group is presented in the following figure:

Plot of Means

v AGE M a m Effect

P F(3,36)=8.94; p<.0001

G 4.23

Figure 2: Means of evaluative devices used at different age group Table 2 showed the mean of each evaluative device used.

Table 2: Mean number of each evaluative device used, and bracketed, mean proportion of

Age 5 7 9 23 evaluative devices. Frames of mind 2.100(4.646) 4.800 (7.715) 10.60 (13.80) 11.70(17.92) Evaluative Devices Negative qualifiers 2.100(5.237) 3.900 (6.958) 5.400(8.114) 6.800 (10.92) Hedges 0.100(0.256) 0.300 (0.546) 0.700 (0.936) 0.600(1.076) Character speech 1.700(3.701) 3.100 (4.508) 2.800(4.516) 1.700 (2.954) Causal connector 0.100 (0.217) 0.200 (0.341) 1.200(1.626) 2.400(4.111)

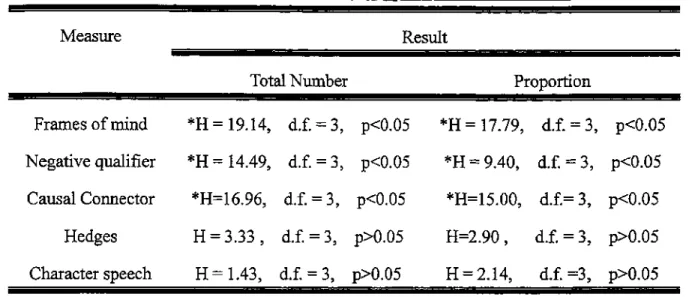

To investigate the change in use of particular evaluative devices across age groups, Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA was computed for the five evaluative devices. Results showed that there is significant increase in the use of frames of mind, causal connectors and negative qualifiers, but there was no significant difference found in the use of hedges and character's

speech. Detail results are as follow:

Table 3: Results of Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA on five Measure

Total Number

types of evaluative devices Result Proportion Frames of mind *H = 19.14, d.f = 3, p<0.05 *H = 17.79, d.f = 3, p<0.05 Negative qualifier *H= 14.49, d . f - 3 , p<0.05 *H = 9.40, d.f = 3, p<0.05 Causal Connector *H=16.96, d.f. = 3, p<0.05 *H=15.00, d.f=3, p<0.05 Hedges H = 3.33, d.f = 3, p>0.05 H=2.90, d.f = 3, p>0.05 Character speech H = L 4 3 , d.f = 3, p>0.05 H = 2.14, d.f. =3, p>0.05 * = significant results

Mann-Whitney U test was then carried out to determine where the difference lies in. Details of results are reported as follow:

Frames of mind. Results of Mann-Whitney U test are shown in table 4. Table 4: Result of Mann-Whitney U test for the use of frames of mind

Age Result Total Proportion 5 v s 7 5 v s 9 5 vs23 7 v s 9 7vs23 9 v s 2 3 U = 23.00, U = 11.00, U =1.000, U= 29.00, U = 12.50, U = 41.50, p<0.05 p<0.05 p< 0.05 p>0.05 p<0.05 p>0.05 U = 26.50, p>0.05 U = 17.00, p<0.05 U = 3.00, p<0.05 U = 32.00, p>0.05 U = 9.00, p<0.05 U = 32.00, p>0.05

Results of Mann-Whitney U test revealed that significant difference lied between 5 and 9 year old and between 7 year old and adult. As noted in figure 3, the use of frame of mind

and 9 year old, although statistical analysis does not showed significant results. Negative qualifiers Results of Mann-Whitney U test are shown in table 5 Table 5: Result of Mann-Whitney U test for the use of negative qualifiers

Age Result Total Proportion 5 v s 7 U=27.00, p>0.05 U=42.00, p>0.05 5 v s 9 U = 26.00, p<0.05 U= 27.00, p>0.05 5vs23 U = 5.50, p<0.05 U = 11.00, p<0.05 7 v s 9 U = 32.50, p>0.05 U= 42.00, p>0.05 7 v s 2 3 U = 23.50, p<0.05 U= 25.00, p>0.05 9 v s 2 3 U = 36.00, p>0.05 U = 29.00, p>0.05

Results of Mann-Whitney U test revealed that significant difference lied between 5 year old and adult. Again, there is gradual increase in the use of negative qualifiers across age groups.

Causal Connector Results of Mann-Whitney U test are Table 6: Result of Mann-Whitnev U test for the use

Age 5 v s 7 5 v s 9 5vs23 7 v s 9 7vs23 9vs23 Total U = 45.00, p>0.05 U=18.5,p<0.05 U = 12.00, p<0.05 U=22.00, P< 0.05 LM14.00, p<0.05 U = 34.00, p>0.05 shown in table 6 of causal connectors Result Proportion U = 46.00, p>0.05 U= 21.50, p<0.05 U=14.00, p<0.05 U=24.00, p<0.05 U=15.00,p<0.05 U = 33.00, p>0.05

Hedges and Character's Speech There was no significant difference found across age in both the use of hedges and character's speech.

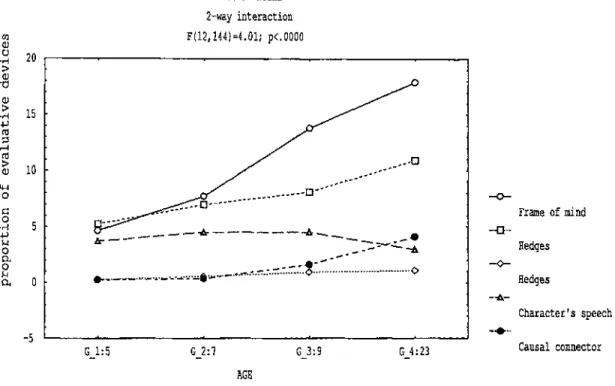

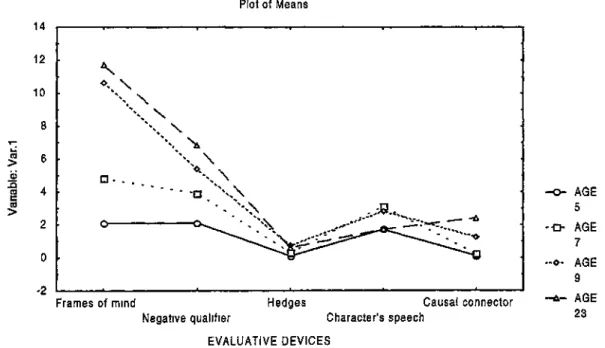

Means of each evaluative device was plot against age in the figure below:

Plot of Means 2-way interaction F(12,144)=4.01; p<.0000

G 1:5 G 2:7 G 3:9 G 4:23

AGE

Figure 3: Means of each evaluative device used across age

Frame of mind --0--Hedges Hedges Character's speech Causal connector

Patterns of evaluative devices used across age

Friedman ANOVA was used to analyze difference in the use of the five types of evaluative device in each age group. Results showed that the pattern of evaluative devices used by five year old was similar to the seven year olds. Children used significant more frames of mind than hedges (Xr2= 8.00, p<0.05), and causal connector (Xr2= 8.00, p<0.05).

They also used significantly more negative qualifiers as compared to hedges (Xr2= 10.00,

p<0.05) and causal connector (Xr2= 9.00, p<0.05). In addition children will use significantly

less hedges (Xr2= 7.00, p<0.05) and causal connector (Xr2= 8.00, p<0.05) than character's

For the nine-year-olds, they use significantly more frames of mind as compared to hedges (Xr2= 10.00, p<0.05) and causal connector (Xr2= 10.00, p<0.05). They also use

significantly more negative qualifiers as compared to hedges (Xr2= 10.00, p<0.05),

character's speech (Xr2= 4.50, p<0.05) and causal connector (Xr2= 10.00, p<0.05).

Furthermore it was found that nine-year-old children used significantly less hedges then character's speech (Xr2= 4.50, p<0.05)

For the adults, they tends to use significantly more frames of mind as compared to character's speech (Xr2= 9.00, p<0.05), hedges (Xr2= 10.00, p<0.05) and causal connector

(Xr = 10.00, p<0.05). Moreover, they would use significantly more negative qualifiers than

hedges (Xr2= 10.00, p<0.05), character's speech (Xr2= 5.44, p<0.05) and causal connector

(Xr = 9.00, p<0.05). In addition, it was found that hedges would be used significantly less

than character's speech (Xr2== 4.50, p<0.05)

Figure 4 summarize the pattern of evaluative devices produced by children:

Plot of Means

- O - AGE 7 --•- AGE

9

Frames of mind Hedges Causal connector ~*~ A G E

Negative qualifier Character's speech 2 3

EVALUATIVE DEVICES

Figure 4: Pattern of evaluative devices produced.

12 10 $ CO > 4 [ -O ^ <\ \ \ x \ \ x< x \ ^

X

v *- \ * * * ^ ft ~ * . Xv L C ^ * * ^ ^ w * . \ t ' • • i '" • i " 1 • -<Discussion

After carrying out the statistical analysis, it was found that children's narrative length increased significantly with age as measured by the total number of clauses produced. Use of evaluative devices increased across age also. Among the five types of evaluative devices under investigation, the use of frames of mind, negative qualifiers and causal connector will increase significantly with age. The following section will investigate the phenomenon observed.

Narrative length

It was found that the mean length of narrative produced by children increases from 5 year old to 9 year old, but decreases slightly from 9 year old to adult. Although narrative produced becomes shorter, it do not result in impoverish narrative content. This may due to the fact that adults tends to organize and condense their story around a central main theme, which makes their narrative shorter while preserving the quality of narrative produced. This phenomenon was observed in Bamberg & Damrad-Frye (1991)'s study also, in which they found that narrative produced by nine year old was shorter than narrative produced by five year old, but the quality of narrative was preserved.

Frames of mind

Analysis result showed that there is significant increase in the use of frames of mind from age five to adult. It is suggested that children's development in general cognitive ability and pragmatic skills have motivated this increase, detail discussion will be presented in the following section.

Development in pragmatic skills. When young children tell story, they usually rely on listener to anticipate reactions of the character (Ninio & Snow, 1996). With listener's active

anticipation, children could sometimes alight perspective successfully without expressing the character's reactions. However, when age increases, pragmatic skills improve, children become aware that they should not assume alignment of perspective by listener's anticipation of the reaction. They then start to make use of linguistic strategies to convey appropriate reaction (Ninio & Snow, 1996). One of the linguistic strategies used to convey reactions include devices that express the character's mental states, which is included in the frames of mind. Therefore, it was suggested that that pragmatic development would lead to increase in use of the frames of mind.

Cognitive development. Another possible explanation for increased use of frames of mind across age is the development in cognitive skill called the theory of mind. Theory of mind may simply means knowledge about the mind. Development in theory of mind concerns children's ability to represent mental representations, which involves understanding of mind, what it is and how it works. This theory about the mind generally emerge around the age of 4 to 5 (Flavell, Miller & Miller, 1993). By the age of 4, children starts to forms model about other people's representation, they gain more knowledge about the mind, especially the nature of representation. Children by this age start to understand that there is no single accurate representation for one object, and that the same object may be represented differently with the possibility of forming false representation. They also understand that what other people represent may be different from what they actually experience. All these understanding lead to appreciation of false-believe and appearance-reality distinction (Flavell, Miller & Miller, 1993). Referring back to the issue concerning the use of frames of mind in narrative. To attribute feelings or thought to the character in story telling task, children have to form a model concerning the protagonist's mental activity. As mentioned above, children

would have acquired some basic knowledge about the mind by the age of 4 to 5, this fact could explain why the use of evaluative device frames of mind was already observed in the narratives produced by 5-years old children. However, theory of mind continues to develop throughout the childhood. Schwanenflugee and Henderson (1998) suggested that children's theory of mind continues to develop in the middle childhood, and children would gain better understanding of the relationship between different mental functions. It is expected that with better understanding of different mental functions, children would be able to use more sophisticated mental terms in referring to mental states. When more sophisticated mental terms are available and mental activity could be more adequately described, it may lead to overall increase in the use of frames of mind.

To support the hypothesis, closer inspection of the data was carried out. It was observed that older children will use more variety and more sophisticated mental terms in referring to the character's thought and feelings. For example, mental terms like MM "surprise", 3§5S "nervous", ^M "hope", $ ^ "decide" was found to be use in adults subjects only.

Apart from these, it was also observed that younger children would sometimes use mental verbs in referring to actual actions rather than mental states. For example:

(1) Narrative produced by a 9-year-old child

mk ommmmmm/hm^mM&^

" After that the dog and the boy want to go to the forest " (2) Narrative produced by a 7 -year-old child

omnnmJinmtti^ttiWM

" The frog want to go out to play "

state of want, rather, it acts like a gap filler. The protagonist in the above two examples has actually finished the action already, but not just "think" of doing as what has suggested in the narrative. This may be explained by the phenomenon of objective referent in which children would sometime use mental terms in referring to behavioral event (Wellman & Estes, 1987). As a result, these seems to agree with what we previously predicted that when children's theory of mind undergoes elaboration throughout the childhood, they will be able to use more sophisticated mental terms, and more reference to frames of mind will be used in narrative.

It was also observed that young children tend to use emotional ternis in response to character's facial expression in the picture, for example: pfl;h(happy), Jgf (angry) while adults would attribute feelings to the character whenever there is need, regardless of presence of picturable facial expressions, like | f i f (surprise), §f g|| (nervous) when there is need.

Younger children may not process the level of inference that is needed for referring to mental state and thought of the character abstract away from the picture (Berman & Slobin, 1994). Again, this increase in ability to make inference about the character's mental state beyond the picture would lead to increase in frames of mind used, and children will become less relie on picture cues to produce frames of time when age increases.

The findings for frames of mind agrees with what have been found in the study carried out Bamberg and Damrad-Frye (1991) and in the study carried out by Berman &

Slobin (1994). These studies have used picture story-book Frog where are you? (Mayer, 1969) to elicit narratives from children, which means that with similar elicitation procedure and the same genre under investigation, Cantonese and English speaking children will showed similar use of frames of mind in their narrative.

Negative qualifiers

Apart from increase in use of frames of mind, increase in use of negative qualifiers was also found. According to Labov (1972), negation will be used when there is contradiction to expectation that something would happen, and they draw on a cognitive background considerably wider than those of the observable events (Labov, 1972). It is hypothesized that when age increases, children's thought would become less concrete and less "picture bond", as a result, they could make reference to things that did not happened, and contrast them with things that have happened. This would lead to increase in negative qualifiers used with age.

However, Ely, McGibbon & McCabe (2000) suggested a contrasting view. Their study investigated production of negatives in both personal and story-book elicited narratives. Results showed that, in picture book elicited narrative, the use of negative decreases from age 5 to age 9. The author suggested that when children become more literal, they would be more concrete and stick to facts, and therefore less willing to describe what did not happened. However, this study, in contrast, found that there is a gradual increase in negation used. It was hypothesize that this discrepancy in findings may due to cultural difference. For Cantonese speaking children, being more literal would probably mean having more exposure to different kinds of text. With more exposure to text, which includes stories, children would become less concrete as a result of being more imaginative. Findings in this study seem to support this point of view.

Apart from that it was hypothesized that, with development in cognitive ability, children could represent the expectation of protagonist. Therefore, they could mention expectations that are needed in necessary situation.

Increase in use of causal connectives with age contradicted with the result of the study done by McCabe and Peterson (1985). They showed that children of very young age could already attribute psychological causality to events, with no age difference between 3;06 to 9;06. However, in this study, young children used significantly smaller amount of causal connectors, in which they seldom attribute psychological or physical causality to events. Most of their stories are merely description of pictures and events. The discrepancy between findings may be due to difference in methodology employed, in which McCabe and Peterson (1985) used personal narrative and this study used story-book elicited narratives. According to Uccelli, Hemphill, Pan & Snow (1999) fantasy narrative and personal narrative will draws on different and separate sets of linguistic and pragmatic competencies, therefore, difference in findings may attribute to difference in genre elicited.

Although children are able to understand and express causal contingency in preschool years already, but their ability to produced causally coherent narrative was still limited.Tt was suggested that the ability to understand and use causal connector by young children in

narrative might be limited by their unfamiliarity to the event (Johnston & Welsh, 2000). Moreover, it may due to the fact that children's ability to produce causal connector is hindered by the demands of joining the themes, characters, symbols and plots together (Kemper & Edwards, 1986).

Also an additional explanation for increase use of causal connector was that as mentioned, with development in pragmatic ability, children become more able to take listener's

perspective. Therefore, they will provide "cause" and "effect" that is relevant to the understanding of the whole story, but not simply assuming all that it is known already. Patterns of evaluative devices used

It was observed that the relative frequency of evaluative device produce by 5-year-old children was similar to 7 year-old children. Each evaluative devices was used rather equally often, while when age increases, frames of mind will be use more intensively. This funding is consistent with the finding from Bamberg & DamradJPrye (1991). Bamberg & DamradJFrye (1991) suggested that theory of mind is undergoing organization and reorganization in the course of development, as a result, a particular evaluative device gains preference when age increased.

To summarize, children's increasing ability to use the evaluative devices frames of mind, negative qualifiers and causal connectors may be motivated by important cognitive, pragmatic as well as linguistic development during this period. It seems that these three evaluative devices are more commonly used and would undergo gradual change over age.

Clinical Implications

In the view of the importance of production of narrative to academic achievement, and the importance of evaluative devices to narrative production. A more detailed

understanding of the use of evaluative devices in children's narrative is needed. It would be better to consider both the communication function and the structural aspects of narrative production rather than just focusing on the structural aspects only. Some children may be able to produce a logical account of events, but they are unable to use evaluative device to "color" their narrative. Training on narrative skills has been focus exclusively on objective structural element, which neglects this essential element in narrative that contributes to the production of socially acceptable narrative. Therefore, this study serves as a preliminary study to provide a picture of the use of evaluative devices in Cantonese children's narrative, this may aid therapy planning for children who could produce coherent and logical

sequence of event but whose narrative is still not socially acceptable. Limitation of the Study

Being a small-scale and an exploratory study, a number of limitations were noted. Firstly, the study analyzed in a total of 40 narratives only taken from 1 primary school and 1 kindergarten. The small sample size might not be representative to the population.

Secondly, as the sample size was small, the influence of individual variability such as individual style and personality, could contribute to the variation in the use of evaluative devices in children. Thirdly, different children showed different level of interest to the story-book which may also affect their performance.

Further Investigation

As mentioned earlier, this study is an exploratory study that investigated the use of evaluative comments in narratives produce by Cantonese children. Further studies could be done using a larger sample size. Furthermore, apart from investigating development in quantity of evaluative devices used only, further investigation could be done on the position of evaluative comments used in narrative.

Apart from that, further investigation could also be done on children's use of other element in narrative like complicating action and resolution. This could provide a more comprehensive picture concerning children's narrative skills.

Also, further study on evaluative comment could be done using other elicitation method, such as personal narratives. This could provide a more detail understanding concerning children's narrative ability in different context, which was supposed to have effected on the narrative structure produced

Conclusion

This study compared the use of evaluative device in narrative elicited by a picture-story book from children in Hong Kong. Results shows that children uses significantly more frames of mind, negative qualifiers and causal connectors with age. Apart from that, this study reveals that children of age 5 and age 7 will use evaluative devices with similar pattern, while children of age 9 and adults will show a distinctive pattern. The results are discussed with the development in the theory of mind and pragmatic skills. The findings from this study can shed light in the development of a narrative intervention program.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank all the children and adults who have participated in this study. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my dissertation supervisor, Dr. Samuel Leung for his generous help during the whole process on my study. Thanks also go to Dr. Alex Francis for his valuable advice.

I would like to thank the Principal, the Vice Principal, teachers and technician of the

Buddhist Chan Shi Wan Primary School.

I wish to thank Ms. Cindy Cheong, Ms. Man Yee Lau and Ms. So Man Fung for their kind consideration and cooperation in data collection and their help with the inter-rater reliability checking. Thanks to the staff of the Department, my friends especially Ms. Maggie Sun, Ms. Connie Lam and Ms. Caroline Lee for their spiritual and intellectual support. Thanks also to my clinical supervisor Ms. Kathy Lee for her spiritual support

Reference

Astington, J. W. (1990). Narrative and child's theory of mind. In B. K. Britton, & A. D. Pellegrini, Narrative thought and narrative language. New Jersy: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates.

Bamberg, M., & Damrad-Frye, R. (1991). On the ability to provide evaluative comments: further explorations of children's narrative competencies. Journal of Child Language, 18, 689-710.

Bee, H. (1997). The Developing Child. New York: Longman.

Berman, R. A., & Slobin, D. I. (1994). Relating events in narrative: a crosslinguistic developmental study. New Jersy: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Capps, L., Losh, M., & Thurber, C. (2000). "The frog ate the bug and made his mouth sad": Narrative comtetence in children with autism. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28(2), 193-204.

Chafe, W. (1990). Some things that narratives tells us about the mind. In B. K. Britton, & A. D. Pellegrini, Narrative thought and narrative language. New Jersy: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Ely, R., MacGibbon, A., & McCabe, A. (2000). She don't care: negatives in children's narratives. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 46 (3), 465-490.

Flavell, J. H., Miller, P. H., & Miller, S. A. (1993). Cognitive development (3rd ed.). New Jersy: Prentice Hall.

Harris, P. L. (1983). Children's understanding of the link between situation and emotion. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 36,490-509.

Disorders. 7 (I): 84-94.

Hedberg, N. L., & Westby, C. E. (1993). Analyzing Storytelling Skills- Theory to Practice. Arizona: Communication Skill Builders.

Johnston, J. R.5 & Welsh, E. (2000). Comprehension of'because' and cso': the role of

prior event representation. First Language. 20. 291-304.

Kemper, S., & Edwards, L. L. (1986). Children's expression of causality and their construction of narratives. Topics in Language Disorders, 7 (1), 11 -20.

Labov, W. (1972). Sociolinguistic patterns. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania UP. Labov, W., & Waletzky, J. (1967). Narrative analysis: oral versions of personal experience. In J. Helm (Eds.), Essays on the verbal and visual arts (pp. 12-44). Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Liles, B. Z. (1993). Narrative discourse in children with language disorders and children with normal language: a critical review of literature. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 36* 868-882.

Macwhinney, B. (1999). The emergence of language from embodiment. In B. MacWhinney (Ed.), The emergence of language (pp. 213-256). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Mayer, M. (1969). Frog, where are you. New York: Penguin Books USA Inc. McCabe, A., & Peterson, C. (1985). A naturalistic study of the production of causal connectives by children. Journal of Child Language, 12,145-159.

^fODfflpooliflA. (1997). Children and narratives: toward an interpretive and sociocultural

approach. In M. Bamberg (Ed.), Narrative development: six approaches (pp. 179-215). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

McCabe, A. (1997). Development and cross-cultural aspects of children's narration. In M. Bamberg (Ed.), Narrative development: six approaches (pp. 137-169). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Ninio, A., & Snow, C. E. (1996). Pragmatic Development. Boulder, colo: Westview Press.

Peterson, C. & McCabe, A. (1983V Developmental psycholinguistics: three ways of looking at a child's narrative. New York: Plenum Press.

Schwanenflugel, P. J., Henderson, R. L., & Fabricius, W. V. (1998). Developing organization of mental verbs and theory of mind in middle childhood: evidence from extensions. Developmental Psychology, 34 ( 3 \ 512-524.

Tannen, D. (1978). The effect of expectations on conversation. Discourse Processes, 1, 203-209.

Uccelli, P., Hemphill, L., Pan, B. A., & Snow, C. (1999). Telling two kinds of stories: source of narrative skill. In L. Baiter, & C. S. Tamis-LeMonda, Child Psychology: A Handbook of Contemporary Issues (pp. 215-233). Philadelphia: Psychology Press.

Wellman, H. M., & Estes, D. (1987). Children's early use of mental verbs and what they mean. Discourse Processes, 10, 141-156.

Wong, Y. M. (1990V Referential choice in spoken Cantonese discourse. Ann Arbor. Mich: University Microfilms International.

Appendix Coding and Analysis

a) Segmenting into clauses

Transcribed narratives are segmented into clauses applying procedures described by Wong (1992). She suggested that "semantically, a clause usually represents an action, an event or a state. Syntactically, a clause contains a single nuclear

predicate around which other predicate-like items may cluster without themselves constituting independent predicates. A predicate in spoken Cantonese can be a verb or an adjective"(Wong, 1992). Following are some examples that are considered to be one clause:

- mxnrmm

- fmnm&mim

For complex sentence, they will be segmented into separate clauses as follow: 1. Subordinate, embedded and coordinate clauses are segmented into separate clauses. Below are examples that was segmented into two separate clauses: (i) Subordinate clause

(ii) Coordinate clause

2. Serial verb constructions will be considered as one clause. For example:

b) Coding

Lexical items are categorized into one of the five categories:

1) Frames of mind: This category include lexical items for reference to i) emotional states

e.g. M "angry", P#[> "happy" ii) emotional states or activities

e.g. H "think", H"hope" iii) Emotional verbs is also included

e.g. ^"frightened". 2) Character speech

i) Direct speech

e.g. W®1£: W% The frog said "good" ii) Indirect speech:

e.g. /jNJK^n^^/JN,[> "The boy told the dog to be careful" 3) Negative qualifiers

(i) Direction negation is included like: ^J "no", ng "not"

4) Hedges:

(i) It consists of lexical devices that suspect the truthfulness of the

proposition,

5) Causal Connectors

(i) This category consists of interclausal connectors like e.g. H ^ (because), $fi^ (so) and ;£(to).

Bachelor of Science (Speech and Hearing Sciences)

First Degree Dissertations

Volume i n

June 2001

Department of Speech and Hearing Sciences

The University of Hong Kong

11 MAR 2)06

Bachelor of Science (Speech and Hearing Sciences)

First Degree Dissertations

Volume ID

June 2001

Lau Wai Heng Sharon The Cantonese FACS: feasibility with aphasic patients Law Choi Hung Rainbow The effect of sentence context on the production of the

Cantonese low-rising tone

Lee Kit Shan Michelle Analysing unrepaired Nepali cleft palate speech Lee Vin Yan Vivian Speech errors and language processing in Cantonese Lee Wai Ling Janise The Effectiveness of Semantic and Syllabic Cues to

Cantonese Aphasic Patients with Naming Difficulties Leung Wing Fai Catherine Evaluative comments in narratives of Cantonese Speaking

children

Liauw Wah Ling Valerie Laryngeal-Supralaryngeal Cyclicity in early Cantonese phonology

Lo Pik Sai Karen Acoustic Cues to the Perception of the Aspiration contrast in Cantonese Initial Stops

Luk Wing Shan Monica The production of aspect markers in Cantonese-speaking children: an experimental study

Ng So Sum Acoustic Analysis of Contour Tones produced by Cantonese Dysarthric Speakers