Natural Outcome of

Helicobacter pylori

Infection in Asymptomatic

Children: A Two-year Follow-up Study

Patrice Serge Ganga-Zandzou, MD*; Laurent Michaud, MD*; Pascal Vincent, MD‡; Marie-Odile Husson, MD‡; Nathalie Wizla-Derambure, MD*; Elisabeth Martin Delassalle, MD§;

Dominique Turck, MD*; and Fre´de´ric Gottrand, MD*

ABSTRACT. Background and Objectives. It is known that Helicobacter pylorican be acquired in early child-hood. There is not enough data to know whether or not infected children should be treated. A better knowledge of the natural outcome and implications ofH pylori in-fection may provide evidence that eradication therapy is beneficial in childhood. This prospective study looks at clinical symptoms, endoscopic, microbial, and histologic changes during a 2-year period in infected asymptomatic children. It is hoped that some prognostic indicators will be found that select out the children that later need therapy.

Patients and Methods. During epidemiologic study

of the prevalence ofH pyloriinfection, 18 children aged 76 4 years (mean 61 SD) were discovered to have H pylori infection and enrolled in the 2-year follow-up study. These patients had received no eradication ther-apy because they were asymptomatic. The follow-up for each patient consisted of an initial assessment, a clinical examination every 6 months, and an endoscopic reeval-uation at the end of the first and second years. Gastric mucosal samples were analyzed for bacteriologic and histologic changes. Various factors were initially record-ed: individual factors included sex, age, and housing conditions; microbial factors included bacterial load and the presence of the CagA gene. Inflammatory changes were also noted, such as the presence of active gastritis and nodular formation, and these were correlated with the histology which was described using the Sydney classification. Typing polymerase chain reaction-restric-tion fragment length polymorphism was performed to check the persistence of the same strain of H pylori in each patient.

Results. All of the children were still infected after 2 years with the same strain as in the initial assessment with the exception of 1 child whose infection cleared spontaneously. The density of antral and fundal mucosal colonization withH pylori also remained stable. There were progressive inflammatory changes in this cohort, particularly between the first and second year (histologic score, 3.561.3 vs 561). Active antral gastritis occurred in 3 out of 14 and 1 out of 8 children during the first and second year, respectively. Gastritis became active in the

fundus in 2 out of 14 and 2 out of 8 children during the same period. Increases in the histologic score were found particularly in male children, and children colonized by

cagA2 strains of H pylori during the follow-up. The frequency of nodular gastritis significantly rose from 11% (2 out of 18 children) to 64% (9 out of 14 children) after 1 year, and to 80% (8 out of 10 children) after 2 years.

Conclusion. These findings demonstrate a deteriora-tion in the histologic features of the gastric mucosa of infected children despite stable H pylori colonization and the absence of symptoms. Pediatrics 1999;104:216 – 221;Helicobacter pylori, child, gastritis.

H

elicobacter pylori infection is known to be ac-quired early in childhood1and has beende-scribed in infants aged 6 days, 5 to 7 weeks, and 2.5 to 5.5 months.2–5It is thought to be frequently

acquired before 5 years of age, both in the industri-alized world6and in developing countries.7,8

Sponta-neous eradication is an unusual phenomenon.4Once

colonized byH pylori, the gastric mucosa is the focus of a chronic infection that is thought to persist indef-initely. This long-term infection can cause severe pathology. Various gastroduodenal diseases seen in adults are known to be linked to H pyloriinfection. These include: gastric and duodenal ulcers, gastric lymphoma, atrophic or metaplastic gastritis, and gas-tric adenocarcinoma.9In children, histologic changes

are mild to moderate and the outcome of an infection diagnosed at an early stage in children remains un-known.7,10 Because the implication ofH pyloriin

ab-dominal and digestive symptomatology has not been clearly identified, there is too little data to know whether or not infected children need to be treated. Better knowledge of the natural outcome ofH pylori infection could provide rationale for eradication, screening, and even a vaccination policy.

To assess the natural evolution of the infection and the outcome in infected children, we conducted a 2-year follow-up study on microbial, histologic, en-doscopic, and clinical evolution in asymptomatic children. Furthermore, follow-up of these patients may identify prognostic indicators that could be used to select those requiring early eradication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS Patients

Between August 1993 and February 1995, 518 children were included in an epidemiologic study on the prevalence ofH pylori

infection in the population of children undergoing

esophagogas-From the *Unite´ de Gastro-ente´rologie, He´patologie et Nutrition, Clinique de Pe´diatrie, Hoˆpital Jeanne de Flandre, Lille, France; the ‡Laboratoire de Bacte´riologie, Faculte´ de Me´decine, Lille, France; and the §Service d’Anatomie et de Cytologie Pathologique, Faculte´ de Me´decine, Lille, France.

Received for publication Nov 13, 1998; accepted Feb 17, 1999.

Address correspondence to Fre´de´ric Gottrand, MD, Unite´ de Gastro-ente´r-ologie, He´patologie et Nutrition, Clinique de Pe´diatrie, Hoˆpital Jeanne de Flandre, 59037 Lille, France. E-mail: fgottrand@chru-lille.fr

troduodenoscopy. Forty-four children out of the 518 were found to have an infection (Fig 1). In these patients, the diagnosis ofH pyloriinfection was based on histology and/or bacteriology. Eigh-teen of these, discovered by chance to be infected by H pylori, underwent upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy for other rea-sons including: suspicion of esophagitis (n58), gastritis (n52), small bowel biopsy for celiac disease (n55), portal hypertension (n52), and perendoscopic gastrostomy (n51). These 18 children (Fig 1) included 8 patients completely free from digestive symp-toms (esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed in these chil-dren for possible celiac disease, portal hypertension follow-up, and requirement of perendoscopic gastrostomy) and 10 presenting with abdominal pain, vomiting, and hematemesis. In the latter, digestive symptoms disappeared after treatment against esoph-agitis (prokinetics and antacids), as a result no anti-H pylori ther-apy was started because the symptoms were considered to be related to esophagitis and not to theH pyloriinfection. These 18 patients were included in a follow-up study for at least 2 years. If digestive symptoms related toH pyloriinfection occurred during the follow-up (abdominal pain, vomiting), treatment for eradica-tion ofH pyloriinfection was given and the child was excluded from the follow-up. This study was approved by the Lille Univer-sity Hospital Ethical Committee. Informed consent of each patient and parents was obtained before their inclusion in the study.

In all of the patients, the diagnosis ofH pylori infection was based on the isolation ofH pylorifrom gastric biopsy specimens. Factors potentially linked to evolution of infection were recorded including: individual factors (sex, age, and housing conditions); microbiologic factors (density of colonization, CagA gene); and gastritis characteristics (visualization of nodule by endoscopy, presence of active gastritis).

The follow-up protocol included an assessment of clinical symptoms (every 6 months) and 2 gastroscopies (1 and 2 years after theH pyloriinfection diagnosis) for endoscopic evaluation, and bacteriologic and histologic studies. To exclude cases of pos-sible multiple and recurrent infections by variousH pyloristrains, genomic fingerprinting was performed on each sample to check the persistence of the same strain ofH pyloriin each patient.

Eleven girls and 7 boys, ages 1 to 17 years (mean6SD57.46 4.4 years) were included in the follow-up study. After 1 year, 14 of the 18 children underwent endoscopy. After 2 years, the number of children followed-up was 10. Among the 4 children who did not return for follow-up at 1 year, 2 underwent endoscopy at the second year and the remaining 2 refused endoscopy. Among the 14 children seen after 1 year, 8 were examined endoscopically again after 2 years (the other 6 were excluded from follow-up— 4 cases with abdominal pain requiring a prescription of anti-H pylori

treatment (omeprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin); these pa-tients did not differ with those who remained asymptomatic dur-ing the follow-up, on endoscopic, histologic, or bacteriologic fea-tures, both initially and at 1 year of follow-up (1 patient with documented spontaneous clearance of infection and 1 case of refusal).

Endoscopy

Before esophagogastroduodenoscopy each child received pre-medication consisting of midazolam and atropine. An Olympus GIF XP20 fiberendoscope was used for all the children. Nodular gastritis was defined by the presence of one or more nodular features on at least the antral mucosa, and erythematous gastritis was described when the gastritic mucosa appeared friable and erythematous. Three antral and two fundal biopsies were per-formed at each endoscopy for bacteriologic and histologic studies.

Histologic Study

Two biopsy samples (one antral and one from the fundus) were fixed in Bouin’s liquid, embedded in paraffin, cut serially into 5-mm sections, stained with hematoxylin-eosin, and assessed un-der light microscopy. All histologic examinations were performed by a single experienced pathologist (E.M.S.). The histologic changes were quantified according to a score derived from the Sydney classification.11A final score (range, 0 –13) was calculated

as the sum of the histologic features. This accounted for the presence of mononuclear cells in the lamina propria, inflamma-tory cells in the epithelia, glandular atrophy, and intestinal

plasia, which were evaluated as follows: absent50, mild51, moderate52, and severe53, and the presence of polynuclear cells in the lamina propria (absent50, present51).

Bacteriologic Study

Samples for microbiology (2 antral and 1 fundal) were stored in a saline buffer at 4°C and taken to the laboratory within 2 hours. Bacteriologic analysis included direct examination with Gram staining, test of the urease activity (colored reaction in liquid media after 3 hours of incubation at 37°C), and culture. The latter was performed on Columbia agar medium with 10% horse blood, for 3 to 7 days under microaerobic conditions. To obtain quanti-tative results, samples were weighed before homogenization and then plated using the Spiral system (Intertechniques, Saint-Nom, France).12Results were analyzed using the decimal logarithm of

the bacterial population.

The genomic fingerprinting of isolates was performed using the restriction fragment length polymorphism ofH pyloriwithin the

ureB(urease) andhtrA(heat shock protein) genes. The polymerase chain reaction amplified products were digested by AluI and

HaeIII restriction enzymes, as described previously.13

ForCagAgene analysis, the homogenized isolates were grown on Mu¨eller-Hinton agar supplemented with 7% fetal calf serum for 3 days at 35°C under microaerophilic conditions for polymer-ase chain reaction tests. Amplification of the CagA gene was performed with previously described primers.14This study used

theCagAgene-positive strain (H pyloriATCC 49 503) and theCagA

gene-negative strain (strain Tx30a) as controls.

Statistical Analysis

Comparative analysis of quantitative data were done by means of the Student’sttest, using decimal logs for analysis of bacterial population. Discontinuous variables (histologic grading) were compared by the Wilcoxon rank test. Paired tests were performed to analyze evolution in the same patient. Spearman’s coefficient was used to link quantitative variables. A P value ,.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

With the exception of 1 case in which the infection was eradicated, molecular typing of isolates showed that in every child the same strain of H pylori per-sisted during the follow-up. The mean bacterial load remained the same throughout the 2-year period (6.5 to 7 log10 bacteria/g of antral tissue, 6.2 to 6.5 log10

bacteria/g of fundal tissue). Significant correlations were found between theH pyloricolonizations in the antrum and fundus not only at the time of diagnosis but also 1 and 2 years later (r5 0.49, r5 0.76,r 5 0.75, respectively; P , .05). The density of mucosal colonization by H pylori did not vary and for each child the difference was not significantly deviated from the values obtained initially (Table 1).

All of the children had abnormalities in antral mucosal histology at different times during follow-up. An increase in the histologic score of antral tissue was seen in 6 out of 14 children at the first year examination and in 7 out of 8 children at the second year examination, and in fundal tissue of 8 out of 14 and 5 out of 8 children, respectively. Although some children showed a mild decrease in lesional score (5 out of 14 and 1 out of 8 in antrum, 2 out of 14 and 2 out of 8 in fundus, respectively, at examinations of 1 and 2 years), lesions in the cohort significantly in-creased between the first year and the second year in the antrum (histologic score, 3.561.3 vs 561;P, .05) (Table 1). During the follow-up, glandular atro-phy and intestinal metaplasia were never found.

In the antrum, gastritis was still active in 8 out of 14 and 6 out of 8 patients, respectively, at 1 and 2

years (fundus, 6 out of 14 and 4 out of 8 children, respectively). In the remainder, an active antral gas-tritis occurred in 3 out of 6 and 1 out of 2 children, respectively, during the first year and the second year (fundus, 2 out of 8 and 2 out of 4, respectively). Active gastritis disappeared at the first examination in both the antrum and fundus in only 3 children.

At the time of diagnosis of infection, lymphoid follicles were present in 4 out of 18 children in the antrum (fundus, 2 out of 18 patients). During the first year of follow-up, lymphoid follicles appeared in the antrum in 3 children (fundus, 8 children) and disap-peared in 4 patients. Three children had no lymphoid follicles in the antral mucosa (fundus, 4 children). During the second year, lymphoid follicles persisted in 4 children and appeared in 2 patients in the an-trum (fundus, 4 children and 1 child, respectively). During the follow-up, only 2 children had no lym-phoid follicles in the antrum (1 child in the fundus). In the 3 children who had a disappearance of active gastritis, the presence of lymphoid follicles was observed. One of them was the child who pre-sented with spontaneous eradication ofH pylori.

Twelve children of this series were infected by the CagA2strain ofH pyloriand 6 by theCagA1strain. At the first year examination, 5 out of 6 children infected by the CagA1 strain had an active antral gastritis versus 5 out of 8 children infected by the CagA2 strain (active fundal gastritis, 5 out of 6 vs 5 out of 8, respectively); at the second year, 2 out of 3 children infected by theCagA1strain versus 5 out of 5 infected by the CagA2 strain had active antral gastritis (active fundal gastritis, 2 out of 3 vs 4 out of 5, respectively).

Lymphoid follicles were found in the antrum at 1 year in 2 out of 6 children infected by the CagA1 strain versus 5 out of 8 infected by theCagA2strain (in the fundus in 3 out of 6 vs 7 out of 8 children); and at 2 years in 3 out of 3 vs 3 out of 5, respectively, in the antrum (in the fundus in 1 out of 3 vs 4 out of 5, respectively).

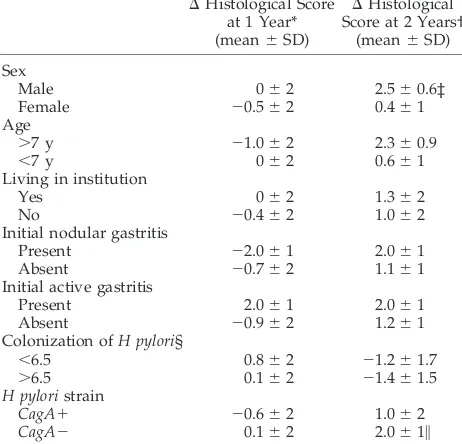

No association was found between the histologic evolution and the initial density of colonization of the mucosa (Table 2). Evolution of the lesions was

TABLE 1. Macroscopic, Histologic, and Bacteriologic Find-ings During the Follow-up

Initial Diagnosis

(n518)

After 12 Months (n514)

After 24 Months (n510)

Macroscopic changes

Nodular gastritis 11% 64%* 80%

Erythematous gastritis 11% 7% 10% Histology† (histological

score: means6SD)

Antrum 3.861.2 3.561.3 5.061.0‡ Corpus 2.261.4 3.161.2 3.762.2 Colonization† (log bact/g

of tissue: means6SD)

Antrum 6.960.7 6.460.4 6.860.4 Corpus 6.561.0 6.260.5 6.260.8

*P,.02: 12 months versus diagnosis.

† Values for the 8 children examined both at 1 and 2 years of follow-up.

neither associated with individual factors (age, living in institution), nor to initial histologic status of the mucosa. In this cohort, children colonized bycagA2 strains of H pylorihad a significant increase in their histologic score in the 2 years after diagnosis (Table 2). Surprisingly, an increase in histologic score was found to be significantly linked to male gender (Ta-ble 2).

At endoscopy, the mucosa showed no more ery-thematous features during follow-up than at initial examination. By contrast, micronodular lymph nodes appeared in 11 children during the follow-up. The frequency of nodular gastritis significantly rose from 11% (2 out of 18) to 64% (9 out of 14) at 1 year and to 80% (8 out of 10) at 2 years. Occurrence of nodular gastritis during the follow-up period was not associated with individual, histologic, or bacte-rial factors.

Clinically, abdominal pain and vomiting initially attributed to esophagitis recurred in 4 cases after 1 year of follow-up despite treatment against gastro-esophageal reflux. These 4 patients received an an-ti-H pylori treatment with no further follow-up. In these patients, the antral and fundal gastritis was still active after 1 year and nodular gastritis had ap-peared during the first year in all cases. No factors recorded at the outset could differentiate these 4 cases with clinical manifestations of gastroesopha-geal reflux. No clinical symptoms were found in the other 14 children during the follow-up.

DISCUSSION

During this follow-up, the levels of both antral and in fundalH pyloricolonization remained unchanged

and abdominal pain was rare in these initially asymptomatic patients despite histologic evidence of increased damages to the gastric mucosa. The present 2-year follow-up study of H pyloriinfection with histologic reference is the first performed in childhood. To the best of our knowledge, there is only one study in adults that addresses the evolution of histologic changes which was done during a 10-year period.15 In childhood, the follow-up studies

that were previously published include only sero-logic or breath-test data.16,17

This study has some methodologic limitations. At inclusion we may have introduced some bias due because of a selection of an asymptomatic population and, furthermore, 6 children were lost on follow-up. From our point of view, it was unethical not to treat H pylori infection when children presented with di-gestive symptoms. So the 4 children presenting with abdominal symptoms 1 year after diagnosis of infec-tion received treatment againstH pyloriand were not followed-up, because the goal of the study was to assess the natural history of H pylori infection in asymptomatic children. Thus, we have no informa-tion on the natural history of H pylori infection in symptomatic children. The loss of 6 children was not simply linked to the absence of symptomatology be-cause asymptomatic children were seen again 1 and 2 years after inclusion. An additional point is that this study was limited to 2 years and that features of infection occurring after this period remain un-known and ideally a longer follow-up should be done. Nevertheless, these results give information on the natural evolution ofH pyloriinfection in asymp-tomatic children.

There is no specific symptomatology related to H pylori infection in children18 apart from the

associa-tion between H pylori infection and duodenal ul-cer.19 –21 The role of H pylori in recurrent abdominal

pain is still controversial.22,23 Both in adults and in

children, asymptomatic H pylori infection has been reported previously.24 –29 All these studies are from

cross-sectional surveys without information concern-ing the duration of H pylori infection. Our results show that most initially asymptomatic-infected chil-dren remained asymptomatic during a 2-year time period despite a deterioration at histologic level.

This follow-up study also demonstrated an in-crease in the severity of histologic damages on antral mucosa after 2 years. In one adult study of patients with persistentH pyloriinfection without eradication therapy, it was found that during a 10-year period there was a regression of antral gastritis and both progression and regression of superficial inflamma-tory changes in the fundus.15Active chronic gastritis

and nonactive chronic gastritis are the histologic changes commonly described at light microsco-py,30 –32 but the gastric mucosa may still be

nor-mal.31,33,34 In the present study all the children

pre-sented with histologic abnormalities of the antral mucosa but not of the fundal mucosa, and most of the patients had a persistence of active gastritis or the appearance of active gastritis. However, glandular atrophy and intestinal metaplasia were not found in any of our patients during the follow-up. In the adult

TABLE 2. Factors Influencing Evolution of Histological Score DHistological Score

at 1 Year* (mean6SD)

DHistological Score at 2 Years†

(mean6SD)

Sex

Male 062 2.560.6‡

Female 20.562 0.461

Age

.7 y 21.062 2.360.9

,7 y 062 0.661

Living in institution

Yes 062 1.362

No 20.462 1.062

Initial nodular gastritis

Present 22.061 2.061

Absent 20.762 1.161

Initial active gastritis

Present 2.061 2.061

Absent 20.962 1.261

Colonization ofH pylori§

,6.5 0.862 21.261.7

.6.5 0.162 21.461.5

H pyloristrain

CagA1 20.662 1.062

CagA2 0.162 2.061\

*DHistological score 1 year5difference of histological scores between 1 year and diagnosis.

†DHistological score 2 years5difference of histological scores between 2 years and diagnosis.

‡P,.05.

§ Initial colonization expressed as log10bacteria/g of tissue in

antrum.

series, these histologic lesions remained unchanged after 10 years in patients with persistent infection.15

Two-year follow-up ofH pyloriinfection is probably too short to observe atrophy and metaplasia.

One patient from our series had an apparent spon-taneous eradication ofH pyloriinfection. He became negative for H pylori both histologically and micro-biologically, without mention of treatment againstH pylori. It was checked at follow-up and by practitio-ner recall that this healthy child received also no antisecretory drug during the follow-up and only amoxicillin had been given for a few days for phar-yngitis. Such a treatment is ineffective most of the time to eradicate H pylori infection. Spontaneous clearance of H pylori infection has been rarely re-ported in children monitored by serologic tests16 or

breath tests17and also in adults by serologic or

his-tologic examinations.15 In the present study, the

spontaneous eradication rate was 3.8% children per year, contrasting with the very high reported rate of spontaneousH pyloriinfection clearance that ranged between 22% and 45% in Peruvian children by breath test.17 In an adult series evaluated throughout a

pe-riod of 10 years, 13% of the patients had a spontane-ous disappearance ofH pyloriinfection.15

In adults, a relationship between the gene status CagA1ofH pyloriand gastric ulcer disease or gastric

adenocarcinoma has been demonstrated35 and we

have previously reported that the gene statusCagA1 was associated with more severe gastritis and clinical symptoms in children.14 The present study suggests

that when asymptomatic children are infected by

CagA1 strains, they do not become symptomatic

more often, and that the histologic deterioration is not more rapid than in children infected by CagA2 strains. Among individual factors studied in our study, surprisingly only the male sex and the gene status CagA2 were related to significant deteriora-tion of histologic damages on gastric mucosa.

During the follow-up study, an increase in the frequency of nodular gastritis was observed at en-doscopy. The rate of nodular and erythematous gas-tritis in the initial endoscopies may be underesti-mated and explained by a less thorough examination at this time period. Nevertheless, biopsies on antral and fundal mucosa were performed during all en-doscopies achieved during the prospective endo-scopical study on the prevalence ofH pyloriinfection, so gastric mucosa was carefully looked at during different endoscopies (because a questionnaire on endoscopical findings was filled-up systematically during the prospective study) and nodular forma-tions on gastric mucosa are usually evident. Nodular antral gastritis is a common macroscopical finding in children and young adults infected by H pylori,4,36

although not pathognomonic.37According to various

authors, it occurs in a large range from 30% to 100% of infected children.30,36 The macroscopic findings

found in the present study suggest that the fre-quency of nodular gastritis rises in accordance with H pylori infection duration in children. These endo-scopic results suggest that nodular gastritis findings at endoscopy indicated a chronicH pyloriinfection; a dependence on the duration of the infection could

explain the great difference in the frequency of nod-ular gastritis reported in different studies of children infected byH pylori.30,36

CONCLUSION

In summary, this 2-year follow-up study has shown that the spontaneous clearance of H pylori infection in childhood is a possible but probably rare phenomenon; in most of the cases, significant and moderate aggravation of histologic features occurs with a persistence or appearance of active gastritis and also an increase in the frequency of nodular gastritis, despite a stability of H pylori density on gastric mucosa.

Longer longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the evolution of gastritis of childhood into atrophic gastritis in adults and to predict the best time to start specific anti-H pylori therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sarah de Freitas and James Dinsmore, medical stu-dents at United Medical and Dental Schools (UMDS) London, for proofreading.

REFERENCES

1. The Gastrointestinal Physiology Working Group.Helicobacter pyloriand gastritis in Peruvian patients: relationship to socioeconomic level, age and sex.Am J Gastroenterol.1990;85:819 – 823

2. Raymond J, Bargaoui K, Kalach N, Bergeret M, Barbet P, Dupont C. Isolation ofHelicobacter pylori in a six-day-old newborn. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis.1995;14:727–728

3. Pattison CP, Marshall BJ, Young TW, Vergara GG. IsHelicobacter pylori the missing link for sudden infant death syndrome?Gastroenterology. 1997;112:A254

4. Thomas JE, Gibson GR, Darboe MK, Dale A, Weaver LT. Isolation of Helicobacter pylorifrom human faeces.Lancet.1992;340:1194 –1195 5. Gottrand F, Turck D, Vincent P.Helicobacter pylori infection in early

infancy.Lancet.1992;340:495

6. Rowland M, Kumar D, O’Connor P, Daly LE, Drumm B. Reinfection withHelicobacter pyloriin children.Gastroenterology.1997;112:A273 7. Ashorn M. What are the specific features ofHelicobacter pylorigastritis in

children?Ann Med.1995;27:617– 620

8. Mitchell HM, Li YY, Hu PJ, et al. Epidemiology ofHelicobacter pyloriin southern China: identification of early childhood as the critical period for acquisition.J Infect Dis.1992;166:149 –153

9. Kokkola A, Valle J, Haapiainen R, Sipponen P, Kivilaakso E, Puolak-kainen P.Helicobacter pyloriinfection in young patients with gastric carcinoma.Scand J Gastroenterol.1996;31:643– 647

10. Ashorn M, Ma¨ki M, Ha¨llstro¨m M, et al.Helicobacter pyloriinfection in Finnish children and adolescents. A serologic cross-sectional and fol-low-up study.Scand J Gastroenterol.1995;30:876 – 879

11. Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P, and the participants in the International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney sys-tem.Am J Surg Pathol.1996;20:1161–1181

12. Gilchrist JE, Campbell JE, Donelly CB, Peeler JT, Delaney JM. Spiral plate method for bacterial determination. Appl Microbiol.1973;25: 244 –252

13. Clayton CL, Kleanthous H, Morgan DD, Puckey L, Tabaqchali S. Rapid fingerprinting ofHelicobacter pyloriby polymerase chain reaction and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis.J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1420 –1425

14. Husson MO, Gottrand F, Vache´e A, et al. Importance in diagnosis of gastritis of detection by PCR of thecagAgene in Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from children.J Clin Microbiol.1995;:33:3300 –3303 15. Niemela S, Karttunen T, Kerola T.Helicobacter pyloriassociated gastritis.

Evolution of histologic changes over 10 years.Scan J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:542–549

16. Granstro¨m M, Tindberg Y, Blennow M. Seroepidemiology of Helicobac-ter pyloriinfection in a cohort of children monitored from 6 months to 11 years of age.J Clin Microbiol.1997;35:468 – 470

and 30 months of age.Am J Gastroenterol.1994;89:2196 –2200 18. Reifen R, Rasooly I, Drumm B, Murphy K, Sherman P.Helicobacter pylori

infection in children. Is there specific symptomatology?Dig Dis Sci. 1989;39:1488 –1492

19. Chong SKF, Lou Q, Asnicar MA, et al.Helicobacter pyloriinfection in recurrent abdominal pain in childhood: comparison of diagnostic tests and therapy.Pediatrics.1995;96:211–215

20. Blecker U, Vandenplas Y.Helicobacter pyloriseropositivity in symptom-free children.Lancet.1992;339:1537

21. Gormally SM, Prakash N, Durnin MT, et al. Association of symptoms withHelicobacter pyloriinfection in children.J Pediatr.1995;126:753–756 22. Ashorn M, Ma¨ki M, Ruuska T, Karikoski-Leo R, Haalstro¨m M. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in recurrent abdominal pain of childhood. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.1993;16:273–277

23. MacArthur C, Saunders N, Feldman W.Helicobacter pylori, gastroduo-denal disease, and recurrent abdominal pain in children.JAMA.1995; 273:729 –734

24. O’Donohoe JM, Sullivan PB, Scott R, Rogers T, Brueton MJ, Barltrop D. Recurrent abdominal pain andHelicobacter pyloriin a community-based sample of London children.Acta Paediatr.1996;85:961–964

25. Radhakrishnan S, Al Nakib B, Kalaoui M, Patric J.Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis in Kuwait: endoscopy-based study in symptomatic and asymptomatic children.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.1993;16:126 –129 26. Patchett S, Beatte S, Leen E, Keane C, Morain CO.Helicobacter pyloriand

symptoms of non-ulcer dyspepsia.BMJ.1991;303:1238 –1249 27. Dooley CP, Cohen H, Fitzgibbons PL, et al. Prevalence ofHelicobacter

pyloriinfection and histologic gastritis in asymptomatic persons.N Engl J Med.1989;321:1562–1566

28. Barthel JS, Westblom TU, Havey AD, Gonzalez F, Everett ED. Gastritis

andCampylobacter pylori in healthy, asymptomatic volunteers. Arch Intern Med.1988;148:1149 –1151

29. Blecker U, Hauser B, Lanciers S, Peeters S, Suys B, Vandenplas Y. The prevalence ofHelicobacter pylori-positive serology in asymptomatic chil-dren.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.1993;16:252–256

30. Mitchell HM, Bohane TD, Tobias V, et al.Helicobacter pyloriinfection in children: potential clues to pathogenesis.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;16:120 –123

31. Prieto G, Polanco I, Larrauri J, Rota L, Lama R, Carrasco S.Helicobacter pyloriinfection in children: clinical, endoscopic, and histologic correla-tions.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.1992;14:420 – 425

32. De Giacomo C, Fiocca R, Villani L, et al.Helicobacter pyloriinfection and chronic gastritis: clinical, serologic, and histologic correlations in chil-dren treated with amoxicillin and colloidal bismuth subcitrate.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.1990;11:310 –316

33. Cadranel S, Goossens H, De Boeck M, Malengreau A, Rodesch P, Butzler JP.Campylobacter pyloridisin children.Lancet.1986;1:735–736 34. Gottrand F, Cullu F, Turck D, et al. Normal gastric histology in

Helico-bacter pylori-infected children.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.1997;25:74 –78 35. Lage AP, Godfroid E, Fauconnier A, et al. Diagnosis ofHelicobacter pylori infection by PCR: comparison with other invasive techniques and de-tection ofcagAgene in gastric biopsy specimens.J Clin Microbiol.1995; 33:2752–2756

36. Bujanover Y, Konikoff F, Baratz M. Nodular gastritis andHelicobacter pylori.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.1990;11:41– 44

37. Michaud L, Ategbo S, Gottrand F, Vincent P, Martin de Lassale E, Turck D. Nodular gastritis associated withHelicobacter helmaniiinfection. Lan-cet.1995;346:1499

DISSED FOR OUR SUCCESS

While death is acknowledged at an intellectual level to be inevitable, in each individual case it is felt at an emotional level to be anomalous. Anything short of immortality is medical failure.

Perhaps this helps explain why the medical profession seems to be respected in inverse proportion to its actual ability to cure disease. It was lionized when it could do practically nothing (it was not until 1930, according to one medical historian, that a visit to the doctor was more likely to benefit the patient than damage him). Yet now that its powers are so formidable, it is regarded with cynicism and disrespect.

Dalrymple T. Taking good health for granted.Wall Street Journal, March 31, 1999

DOI: 10.1542/peds.104.2.216

1999;104;216

Pediatrics

and Frédéric Gottrand

Husson, Nathalie Wizla-Derambure, Elisabeth Martin Delassalle, Dominique Turck

Patrice Serge Ganga-Zandzou, Laurent Michaud, Pascal Vincent, Marie-Odile

Two-year Follow-up Study

Infection in Asymptomatic Children: A

Helicobacter pylori

Natural Outcome of

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/104/2/216 including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/104/2/216#BIBL This article cites 36 articles, 5 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/in_memoriam In Memoriam

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/gastroenterology_sub Gastroenterology

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

DOI: 10.1542/peds.104.2.216

1999;104;216

Pediatrics

and Frédéric Gottrand

Husson, Nathalie Wizla-Derambure, Elisabeth Martin Delassalle, Dominique Turck

Patrice Serge Ganga-Zandzou, Laurent Michaud, Pascal Vincent, Marie-Odile

Two-year Follow-up Study

Infection in Asymptomatic Children: A

Helicobacter pylori

Natural Outcome of

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/104/2/216

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.