Premarital Sexual Intercourse Among Adolescents in

an Asian Country: Multilevel Ecological Factors

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: Sexual initiation among adolescents is associated with divorced parents; less education; low income; dropping out of school; permissive attitudes; lack of confidence to avoid sex; peer pressure; drinking; drug use; previous sexual abuse; and exposure to sexual content of media.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: The strongest factor associated with sexual initiation was pornography viewing for boys but previous sexual abuse for girls. Sexual initiation was not associated with factual AIDS-related information, but viewing of HIV/AIDS/STI-infected persons in the media showed a strong protective association.

abstract

OBJECTIVE:The goal was to assess personal and environmental fac-tors associated with premarital sex among adolescents.

METHODS:We conducted a case-control study. Between 2006 and 2008, we recruited 500 adolescents who reported having engaged in volun-tary sex for most recent sex. Five hundred control subjects were matched for age, gender, and ethnicity.

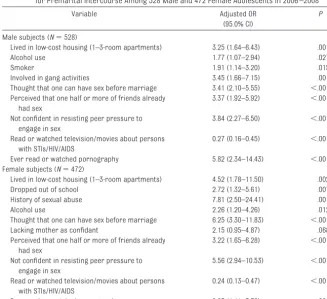

RESULTS:Independently significant factors for premarital sex among boys were pornography viewing (adjusted odds ratio [OR]: 5.82 [95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.34 –14.43]), lack of confidence to resist peer pressure (OR: 3.84 [95% CI: 2.27– 6.50]), perception that more than one half of their friends had engaged in sex (OR: 3.37 [95% CI: 1.92–5.92]), permissiveness regarding premarital sex (OR: 3.41 [95% CI: 2.10 –5.55]), involvement in gang activities (OR: 3.45 [95% CI: 1.66 – 7.15]), drinking (OR: 1.77 [95% CI: 1.07–2.94]), smoking (OR: 1.91 [95% CI: 1.14 –3.20]), and living in low-cost housing (OR: 3.25 [95% CI: 1.64 – 6.43]). For girls, additional factors were previous sexual abuse (OR: 7.81 [95% CI: 2.50 –24.41]) and dropping out of school (OR: 2.72 [95% CI: 1.32–5.61]), and stronger associations were found for lack of confi-dence to resist peer pressure (OR: 5.56 [95% CI: 2.94 –10.53]) and per-missiveness regarding premarital sex (OR: 6.25 [95% CI: 3.30 –11.83]). Exposure to persons with HIV/AIDS or sexually transmitted infections in the media was negatively associated with sex for boys (OR: 0.27 [95% CI: 0.16 – 0.45]) and girls (OR: 0.24 [95% CI: 0.13– 0.47]).

CONCLUSION:Sex education programs for adolescents must address social, media, and pornographic influences and incorporate skills to negotiate sexual abstinence.Pediatrics2009;124:e44–e52

CONTRIBUTORS:Mee-Lian Wong, MBBS, MPH, MD,aRoy Kum-Wah

Chan, MBBS, MRCP, FRCP,a,bDavid Koh, MBBS, MSc, PhD,a

Hiok-Hee Tan, MBBS, MRCP, FRCP,bFong-Seng Lim, MBBS, MMed,c

Shanta Emmanuel, MBBS, MPH,dand George Bishop, MS, PhDe

aDepartment of Epidemiology and Public Health, Yong Loo Lin

School of Medicine andeDepartment of Psychology, Faculty of

Arts and Social Sciences, National University of Singapore, Singapore;bDepartment of Sexually Transmitted Infection

Control, National Skin Centre, Ministry of Health, Singapore;

cNational Health Group Polyclinics, Singapore;dResearch and

Epidemiology Department, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

KEY WORDS

premarital sexual intercourse, adolescents, pornography, sexual abuse, media

ABBREVIATIONS

STI—sexually transmitted infection CI— confidence interval

OR— odds ratio

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2008-2954 doi:10.1542/peds.2008-2954

Accepted for publication Mar 6, 2009

Address correspondence to Mee-Lian Wong, MBBS, MPH, MD, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health (MD 3), Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, 16 Medical Dr, Singapore 117597. E-mail: ephwml@nus.edu.sg PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275). Copyright © 2009 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

Approximately one half of new HIV in-fections and one third of new sexually transmitted infections (STIs) world-wide occur among youths 15 to 24

years of age.1 Although programs

ad-vocating sexual abstinence only

among adolescents found no evidence of impact,2–4programs promoting sex-ual abstinence as the best means of preventing HIV but also encouraging condom use and partner reduction generally were found to reduce sexual initiation and unprotected sex among

youths in high-income5 and

develop-ing6countries.

Presently, adolescents have easy ac-cess not only to sexual content in mov-ies, television, and music videos but also to Internet-based pornography. Longitudinal studies among US adoles-cents found that exposure to sexual

content in television7 and degrading

music lyrics8 predicted sexual initia-tion. In another longitudinal survey,

Brown et al9combined sexual content

across television, movies, music, and magazines and found it to be associ-ated with sexual initiation among white but not black adolescents. Signif-icantly associated factors among the latter were parental disapproval of teen sex and permissive peer sexual

normative behavior. Few studies10–12

have assessed the risk of pornogra-phy, particularly Internet-based por-nography, on teens’ sexual initiation. Therefore, we aimed to determine the extent to which pornography, media, and other parental, school, peer, and personal factors are associated with sexual initiation among adolescents.

METHODS

We conducted a case-control study, comparing characteristics of sexually active adolescents (case subjects) at-tending the only public Department of STI Control clinic in Singapore for screening or treatment of STIs with those of non–sexually active

adoles-cents (control subjects) attending a primary care clinic. Approximately 80% of adolescents with notified STIs attend this public clinic in Singapore. Singapore has a small population of 3.6 million citizens, with the majority (75.2%) being Chinese, 13.6% Malay-sian, and 8.8% Indian.13

Case subjects were local, never-mar-ried, new clinic attendees 14 to 19 years of age who responded yes to the following question: “Did you have sex voluntarily for most recent sex? Sex in-cludes any of these: penis entering the vagina; another person’s mouth ing your genitals or your mouth touch-ing another person’s genitals; or an-other person’s penis entering your anus or your penis entering another person’s anus.” We excluded subjects who reported forced sex and those

who were⬍14 years of age, because

sex among the latter was considered statutory rape.

Control subjects were same-aged ado-lescents who had never engaged in sexual intercourse. Because it is unac-ceptable in Singapore’s conservative society to ask adolescents about sex,

we asked the following questions as nonsensitive proxy indicators of sexual intercourse: “Have you ever gone out

alone with a boyfriend/girlfriend/

other person for some romance or on a date? Have you had close physical contact such as kissing and fondling, beyond just holding hands with him/ her?” Adolescents who responded no to one or both of the aforementioned questions were considered non–sexu-ally active.

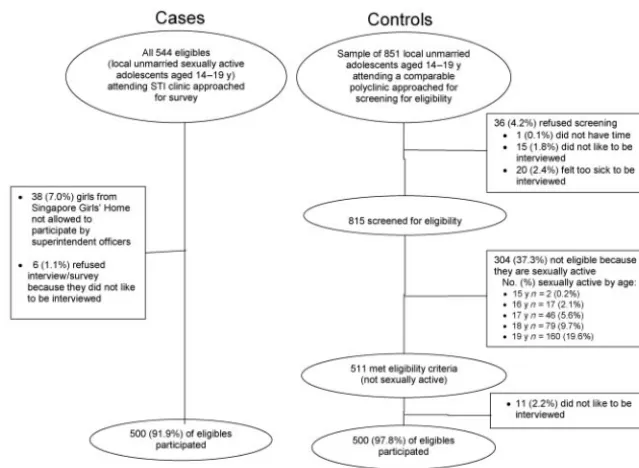

Between August 2006 and April 2008, we recruited 544 case subjects, of

whom 91.9% (n ⫽ 500) responded

(Fig 1). Nonrespondents were younger (14 –16-year-old subjects: 56.8% among nonrespondents vs 13.8% among

re-spondents; P ⬍ .001). Five hundred

control subjects, matched according to age, gender, and ethnicity (response rate: 97.8%), were selected randomly from a public primary health care clinic with comparable ethnic distribu-tion, located⬃20 km from the Depart-ment of STI Control clinic.

This study was approved by the institu-tional review board of the Nainstitu-tional Uni-versity of Singapore. We conducted FIGURE 1

face-to-face interviews, with self-ad-ministered questions on sensitive data placed at the end. Before the interview began, adolescents signed the consent form (age of consent:ⱖ16 years) after receiving an explanation of the study and the patient information sheet. For

subjects who were⬍16 years of age,

accompanying parents, guardians, or juvenile home officers signed the con-sent form and the adolescents signed

the assent form. Only 3 subjects⬍16

years of age were unaccompanied; be-cause they could understand the na-ture of the study and treatment, we fol-lowed the Fraser guidelines and took informed consent from them. Free lab-oratory tests (worth $50) were offered as incentives.

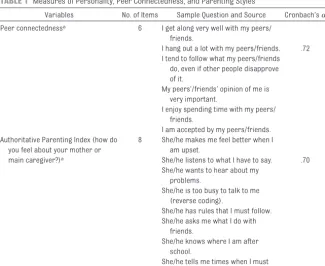

We adapted the multilevel ecological model14to assess the following factors potentially associated with premarital sexual intercourse: sociodemographic variables for parents; family influ-ences, including parental relation-ships, parenting styles,15and

parent-child communication regarding sex; peer influences, including peer norms and peer connectedness16; school

in-fluences, including self-reported

school performance, participation in extracurricular activities, and holding of leadership positions; influences of media; and personal factors such as previous sexual abuse, smoking, drink-ing, drug abuse, gang activities, knowl-edge about HIV/AIDS/STIs, permissive attitudes toward sex, and confidence in resisting peer pressure to engage in sex. Table 1 lists the composite item measures for assessment of peer con-nectedness and authoritative parent-ing style, with their reliability indices

(Cronbach␣values).

To develop measures of sexual content in the mass media, we considered the local context, policy implications, and “legality” of the sexual content/materi-als and the availability of harmful and educational messages on sex for ado-lescents. We classified the sexual con-tent of media into 3 categories,

namely, public-access/free-to-air me-dia approved by the local meme-dia au-thority, “illegal” media, and educa-tional media. Questions in the first category assessed the frequency of ex-posure (on a 4-point scale, ranging from hardly to almost every time) to talk about sex or portrayal of behavior suggesting sexual intercourse from public-access television, movies, mag-azines, books, and popular music. An example of a question is as follows: “Based on the movies you have watched, how often do you (1) hear people talking about having sex and (2) see people who are kissing passion-ately, touching intimpassion-ately, or undress-ing themselves or see a couple half-naked?”

Illegal media are pornographic materi-als depicting explicit sexual inter-course. These are banned, and use was measured with 2 questions, as fol-lows. “How often do you read or watch

pornography (⬘blue’ films, porn, or

movies, videos, or magazines that show naked people having sex)? Where do you mainly watch them (Internet, magazines or comics, video CDs/DVDs/ videos, mobile telephone, or other sources)?”

Questions on educational media per-tained to attendance at talks on STIs or exposure to media portraying persons with STIs/HIV/AIDS or dying as a result of AIDS. An example was a yes/no re-sponse to the statement, “I have watched television programs, movies, or videos on people infected with sex-ually transmitted diseases.”

History of sexual abuse was defined as a yes response to the question, “Did anyone abuse you sexually (had sexual contact with you or made you do sex-ual things to them that you did not want to) before your first voluntary sex?” A school dropout was defined as having dropped out before completing secondary school (equivalent to 10 years of schooling).

TABLE 1 Measures of Personality, Peer Connectedness, and Parenting Styles

Variables No. of Items Sample Question and Source Cronbach’s␣ Peer connectednessa 6 I get along very well with my peers/

friends.

I hang out a lot with my peers/friends. .72 I tend to follow what my peers/friends

do, even if other people disapprove of it.

My peers’/friends’ opinion of me is very important.

I enjoy spending time with my peers/ friends.

I am accepted by my peers/friends. Authoritative Parenting Index (how do

you feel about your mother or

8 She/he makes me feel better when I am upset.

main caregiver?)a She/he listens to what I have to say. .70

She/he wants to hear about my problems.

She/he is too busy to talk to me (reverse coding).

She/he has rules that I must follow. She/he asks me what I do with

friends.

She/he knows where I am after school.

She/he tells me times when I must come home.

To identify independent factors signifi-cantly associated with sexual inter-course, we used unconditional binary logistic regression analysis to esti-mate the adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Although individual matching was used in this case-control study, we used uncondi-tional logistic regression analysis (the approach for unmatched analysis)

be-cause the analysis had already been stratified according to the matching factor of gender, and age and ethnicity were not found to confound the rela-tionship between the factors studied and sexual initiation.

Independent variables with a

statisti-cal significance of ⱕ.1 in univariate

analyses were entered simultaneously

into the logistic regression model with sexual intercourse (yes/no) as the de-pendent variable. Variables were then removed from the equation one at a time, by using stepwise backward elimination, until removal did not lead to a significant decrease in the strength of the equation. Pearson cor-relation coefficients were⬍0.30 for all bivariate relationships tested for the

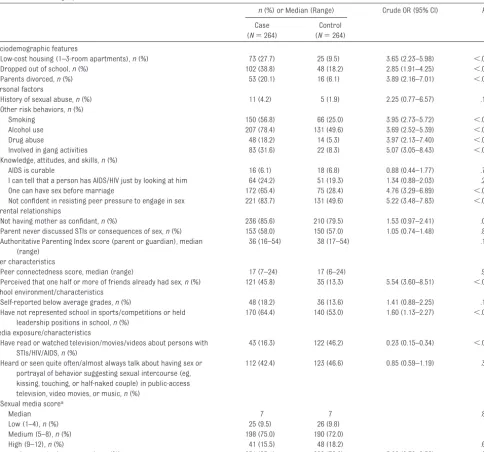

TABLE 2 Sociodemographic, Personal, Parental, Peer, School, and Media Characteristics of Case and Control Male Adolescents in 2006 –2008

n(%) or Median (Range) Crude OR (95% CI) P

Case (N⫽264)

Control (N⫽264) Sociodemographic features

Low-cost housing (1–3-room apartments),n(%) 73 (27.7) 25 (9.5) 3.65 (2.23–5.98) ⬍.001 Dropped out of school,n(%) 102 (38.8) 48 (18.2) 2.85 (1.91–4.25) ⬍.001 Parents divorced,n(%) 53 (20.1) 16 (6.1) 3.89 (2.16–7.01) ⬍.001 Personal factors

History of sexual abuse,n(%) 11 (4.2) 5 (1.9) 2.25 (0.77–6.57) .128 Other risk behaviors,n(%)

Smoking 150 (56.8) 66 (25.0) 3.95 (2.73–5.72) ⬍.001

Alcohol use 207 (78.4) 131 (49.6) 3.69 (2.52–5.39) ⬍.001

Drug abuse 48 (18.2) 14 (5.3) 3.97 (2.13–7.40) ⬍.001

Involved in gang activities 83 (31.6) 22 (8.3) 5.07 (3.05–8.43) ⬍.001 Knowledge, attitudes, and skills,n(%)

AIDS is curable 16 (6.1) 18 (6.8) 0.88 (0.44–1.77) .720

I can tell that a person has AIDS/HIV just by looking at him 64 (24.2) 51 (19.3) 1.34 (0.88–2.03) .206 One can have sex before marriage 172 (65.4) 75 (28.4) 4.76 (3.29–6.89) ⬍.001 Not confident in resisting peer pressure to engage in sex 221 (83.7) 131 (49.6) 5.22 (3.48–7.83) ⬍.001 Parental relationships

Not having mother as confidant,n(%) 236 (85.6) 210 (79.5) 1.53 (0.97–2.41) .067 Parent never discussed STIs or consequences of sex,n(%) 153 (58.0) 150 (57.0) 1.05 (0.74–1.48) .86 Authoritative Parenting Index score (parent or guardian), median

(range)

36 (16–54) 38 (17–54) .100

Peer characteristics

Peer connectedness score, median (range) 17 (7–24) 17 (6–24) .984 Perceived that one half or more of friends already had sex,n(%) 121 (45.8) 35 (13.3) 5.54 (3.60–8.51) ⬍.001 School environment/characteristics

Self-reported below average grades,n(%) 48 (18.2) 36 (13.6) 1.41 (0.88–2.25) .153 Have not represented school in sports/competitions or held

leadership positions in school,n(%)

170 (64.4) 140 (53.0) 1.60 (1.13–2.27) ⬍.01

Media exposure/characteristics

Have read or watched television/movies/videos about persons with STIs/HIV/AIDS,n(%)

43 (16.3) 122 (46.2) 0.23 (0.15–0.34) ⬍.001

Heard or seen quite often/almost always talk about having sex or portrayal of behavior suggesting sexual intercourse (eg, kissing, touching, or half-naked couple) in public-access television, video movies, or music,n(%)

112 (42.4) 123 (46.6) 0.85 (0.59–1.19) .335

Sexual media scorea

Median 7 7 .861

Low (1–4),n(%) 25 (9.5) 26 (9.8)

Medium (5–8),n(%) 198 (75.0) 190 (72.0)

High (9–12),n(%) 41 (15.5) 48 (18.2) .692

Ever read or watched pornography,n(%) 251 (95.1) 209 (79.2) 5.08 (2.70–9.56) ⬍.001

aSum of frequency scores (scores of 1– 4) from the following 3 questions on exposure to public-access media depicting talk on sex or portrayal of behavior suggesting sexual intercourse.

independent variables, which demon-strated no colinearity between inde-pendent variables. Parenting style and

peer connectedness scores were en-tered as continuous variables. Other variables were entered as categorical

variables dichotomized as yes or no.

The significance level was set atP⬍

.05. All data analyses were performed with SPSS 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Of the 500 sexually active teens (52.8% boys and 47.2% girls), almost all were heterosexual, with 16 (3.2%) being ho-mosexual (boys: 5.3%; girls: 0.8%) and 7% bisexual (boys: 6.4%; girls: 7.6%). All except 24 had engaged in vaginal intercourse. Of those 24 adolescents, 23 had engaged in oral intercourse only and 1 had engaged in anal inter-course only. The median age of first sexual intercourse was 16 years (range: 11–19 years), and the median number of partners was 4 (range: 1–11 partners). Approximately two thirds (60.7%) of the last sexual

inter-course episodes were⬍1 month ago,

and only 8% were⬎6 months ago.

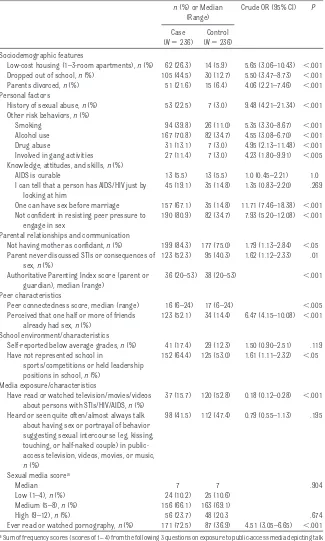

Sexual intercourse among male ado-lescents showed significant associa-tions with living in low-cost housing, dropping out of school, having di-vorced parents, substance (tobacco, alcohol, or drug) use, involvement in gang activities, permissive attitudes regarding premarital sex, lack of con-fidence in resisting peer pressure to engage in sex, perception that one half or more of their friends were sexually active, and not holding leadership po-sitions or participating in competi-tions in schools (Table 2). It showed significant negative association with exposure to persons with STIs or HIV or persons dying as a result of AIDS in magazines, newspapers, television, or movies. Female adolescents showed similar findings, with the following dif-ferences: a history of sexual abuse was significantly associated with sexual initiation, and the median score for au-thoritative parenting was significantly lower among sexually active adoles-cents than among non–sexually active adolescents (Table 3).

TABLE 3 Sociodemographic, Personal, Parental, Peer, School, and Media Characteristics of Case and Control Female Adolescents in 2006 –2008

n(%) or Median (Range)

Crude OR (95% CI) P

Case (N⫽236)

Control (N⫽236) Sociodemographic features

Low-cost housing (1–3-room apartments),n(%) 62 (26.3) 14 (5.9) 5.65 (3.06–10.43) ⬍.001 Dropped out of school,n(%) 105 (44.5) 30 (12.7) 5.50 (3.47–8.73) ⬍.001 Parents divorced,n(%) 51 (21.6) 15 (6.4) 4.06 (2.21–7.46) ⬍.001 Personal factors

History of sexual abuse,n(%) 53 (22.5) 7 (3.0) 9.48 (4.21–21.34) ⬍.001 Other risk behaviors,n(%)

Smoking 94 (39.8) 26 (11.0) 5.35 (3.30–8.67) ⬍.001 Alcohol use 167 (70.8) 82 (34.7) 4.55 (3.08–6.70) ⬍.001 Drug abuse 31 (13.1) 7 (3.0) 4.95 (2.13–11.48) ⬍.001 Involved in gang activities 27 (11.4) 7 (3.0) 4.23 (1.80–9.91) ⬍.005 Knowledge, attitudes, and skills,n(%)

AIDS is curable 13 (5.5) 13 (5.5) 1.0 (0.45–2.21) 1.0 I can tell that a person has AIDS/HIV just by

looking at him

45 (19.1) 35 (14.8) 1.35 (0.83–2.20) .269

One can have sex before marriage 157 (67.1) 35 (14.8) 11.71 (7.46–18.38) ⬍.001 Not confident in resisting peer pressure to

engage in sex

190 (80.9) 82 (34.7) 7.93 (5.20–12.08) ⬍.001

Parental relationships and communication

Not having mother as confidant,n(%) 199 (84.3) 177 (75.0) 1.79 (1.13–2.84) ⬍.05 Parent never discussed STIs or consequences of

sex,n(%)

123 (52.3) 95 (40.3) 1.62 (1.12–2.33) .01

Authoritative Parenting Index score (parent or guardian), median (range)

36 (20–53) 38 (20–53) ⬍.001

Peer characteristics

Peer connectedness score, median (range) 16 (6–24) 17 (6–24) ⬍.005 Perceived that one half or more of friends

already had sex,n(%)

123 (52.1) 34 (14.4) 6.47 (4.15–10.08) ⬍.001

School environment/characteristics

Self-reported below average grades,n(%) 41 (17.4) 29 (12.3) 1.50 (0.90–2.51) .119 Have not represented school in

sports/competitions or held leadership positions in school,n(%)

152 (64.4) 125 (53.0) 1.61 (1.11–2.32) ⬍.05

Media exposure/characteristics

Have read or watched television/movies/videos about persons with STIs/HIV/AIDS,n(%)

37 (15.7) 120 (52.8) 0.18 (0.12–0.28) ⬍.001

Heard or seen quite often/almost always talk about having sex or portrayal of behavior suggesting sexual intercourse (eg, kissing, touching, or half-naked couple) in public-access television, videos, movies, or music,

n(%)

98 (41.5) 112 (47.4) 0.79 (0.55–1.13) .195

Sexual media scorea

Median 7 7 .904

Low (1–4),n(%) 24 (10.2) 25 (10.6) Medium (5–8),n(%) 156 (66.1) 163 (69.1)

High (9–12),n(%) 56 (23.7) 48 (20.3 .674 Ever read or watched pornography,n(%) 171 (72.5) 87 (36.9) 4.51 (3.05–6.65) ⬍.001

aSum of frequency scores (scores of 1– 4) from the following 3 questions on exposure to public-access media depicting talk

For both genders, premarital inter-course was not significantly associ-ated with the wrong knowledge that AIDS was curable and that it was not possible to tell whether a person had HIV/AIDS on the basis of appear-ance alone; academic performappear-ance in school; or exposure to sexual content in public-access music, movies, or tele-vision. Stratification according to age

(14 –16 years orⱖ17 years) and

eth-nicity indicated no discernible differ-ences in factors associated with sex-ual intercourse (data not shown).

In multivariate analysis, the strongest factor associated with sexual inter-course among male adolescents was viewing of pornography (Table 4). Those who viewed pornography were

⬃6 times more likely than those who

did not do so to engage in sexual inter-course. Other independent, signifi-cantly associated factors were living in low-cost housing, alcohol and tobacco

use, involvement in gang activities, permissive attitudes about premarital sex, perception that more than one half of their friends were having sex, and lack of confidence to resist peer pressure to engage in sex. Having read about or watched people with HIV/AIDS or STIs demonstrated a strong protec-tive association with sexual inter-course. Adolescents who had read about or watched characters or per-sons with these diseases were 0.27 times as likely to engage in sex as were those not exposed to them.

For girls, the strongest risk factor for premarital intercourse was a history of sexual abuse. Girls who had been

sexually abused were⬃8 times more

likely to engage in voluntary sexual in-tercourse. They also reported more partners than non–sexually abused girls (age-adjusted mean number of partners: 7.3 vs 4.4;P⬍.001). Other independent factors similar to those

for boys but with stronger associa-tions were permissive attitudes re-garding premarital sex and lack of confidence to resist peer pressure to engage in sex. Like adolescent boys, girls who had viewed or read about persons with HIV/AIDS/STIs were much less likely to engage in sex. Other asso-ciations similar to those for boys were living in low-cost housing, alcohol use, and perception that more than one half of their friends were having sex. Viewing of pornography was also a sig-nificant but less strong risk factor, compared with boys. A significant pre-dictor of premarital intercourse for girls (P⫽.007) but not boys (P⫽.243) was having dropped out of school. Not having a mother to confide in when troubled showed an association that was close to statistical significance for girls (P⫽.068) but not boys (P⫽.16).

Most sexually active adolescents

(⬎70%) had viewed pornography, with

the Internet (59%) being the main source, followed by videos (19%), mo-bile telephones (14%), and magazines (8.1%). Primary self-reported reasons for first sexual intercourse among boys were curiosity (58.7%), love (37.1%), and inability to control them-selves (21.2%). For girls, the reasons were love (49.2%), curiosity (38.6%), and not knowing how to say no (20.3%). Almost one half (43.6%) of the girls and approximately one third (29.5%) of the boys did not intend to have sex in the first place but engaged in sex subsequently because they could not control themselves, lacked the skills to say no, or were under the influence of alcohol or drugs.

DISCUSSION

The strongest factor associated with sexual intercourse was viewing of por-nography for male adolescents but a history of sexual abuse for female ad-olescents. For both genders, a modifi-able factor for sexual intercourse was

TABLE 4 Backward, Stepwise, Multivariate, Logistic Regression Model Indicating Significant ORs for Premarital Intercourse Among 528 Male and 472 Female Adolescents in 2006 –2008

Variable Adjusted OR

(95.0% CI)

P

Male subjects (N⫽528)

Lived in low-cost housing (1–3-room apartments) 3.25 (1.64–6.43) .001

Alcohol use 1.77 (1.07–2.94) .027

Smoker 1.91 (1.14–3.20) .015

Involved in gang activities 3.45 (1.66–7.15) .001 Thought that one can have sex before marriage 3.41 (2.10–5.55) ⬍.001 Perceived that one half or more of friends already

had sex

3.37 (1.92–5.92) ⬍.001

Not confident in resisting peer pressure to engage in sex

3.84 (2.27–6.50) ⬍.001

Read or watched television/movies about persons with STIs/HIV/AIDS

0.27 (0.16–0.45) ⬍.001

Ever read or watched pornography 5.82 (2.34–14.43) ⬍.001 Female subjects (N⫽472)

Lived in low-cost housing (1–3-room apartments) 4.52 (1.78–11.50) .002 Dropped out of school 2.72 (1.32–5.61) .007 History of sexual abuse 7.81 (2.50–24.41) .001

Alcohol use 2.26 (1.20–4.26) .012

Thought that one can have sex before marriage 6.25 (3.30–11.83) ⬍.001 Lacking mother as confidant 2.15 (0.95–4.87) .068 Perceived that one half or more of friends already

had sex

3.22 (1.65–6.28) ⬍.001

Not confident in resisting peer pressure to engage in sex

5.56 (2.94–10.53) ⬍.001

Read or watched television/movies about persons with STIs/HIV/AIDS

0.24 (0.13–0.47) ⬍.001

lack of confidence to resist peer pres-sure, whereas exposure to persons or portrayal of characters with HIV or STIs in the media showed a strong pro-tective association. Other predictors of sexual intercourse were having dropped out of school, having a per-missive attitude toward premarital sex, consuming alcohol, smoking, and living in low-cost housing.

Our study in a clinic-based setting lim-its the generalizability of the findings. However, our primary aim was not to extrapolate our findings but to identify predictors of sexual initiation, for plan-ning of STI/HIV preventive interven-tions targeting high-risk adolescents who attend this clinic. Our study’s strength is that the privacy and longer time available at the clinic allowed the use of a more-comprehensive ques-tionnaire. In addition, we could study school dropouts, who were reported to be at higher risk for engaging in sexual intercourse.17,18 Other study limita-tions included possible bias from self-reports of behavior and the difficulty of demonstrating causality. We at-tempted to reduce self-reporting bias by ensuring anonymity and explaining to the patients that the survey was con-ducted to help us plan better pro-grams to support them.

We identified 2 noteworthy findings of public health significance. First, sex-ual intercourse among adolescents showed a significant independent as-sociation with viewing of pornography, which agrees with the results of a study with high school boys (17–21

years of age) in Sweden.12 However,

the lack of association of sexual initia-tion with exposure to sexual content in television programs, movies, or music in our study did not concur with the

results of the study by Brown et al9

among US adolescents. This might be explained by differences in the classi-fication of sexual content. Portrayals of sexual intercourse and pornographic

magazines such Playboy were

classi-fied under sexual content in media in the study by Brown et al9but were clas-sified separately as pornography in our study. Other explanations could in-volve the difference in the availability of explicit scenes of sexual intercourse in publicly screened movies or televi-sion in Singapore, compared with the United States. Airing of explicit sexual intercourse in public-access movies and television is banned, and persons

⬍21 years of age are not permitted to watch movies portraying sexual inter-course and full nudity.

The second noteworthy finding was the lack of association of knowledge of the incurable nature of AIDS with sexual initiation but the strong protective as-sociation of having heard or seen peo-ple or portrayal of characters with HIV/AIDS/STIs in the media. The latter finding concurs with the results of a study in the United States8that found that black youths who were exposed to depictions of sexual risks in the media were less likely to initiate sexual inter-course. Sexual risk depiction in the media for teens is low in the United States19but high in Singapore, proba-bly because of its school sex education programs. However, there is no stan-dardized curriculum for sex education. The variations in levels of sex educa-tion and the lack of access to sex edu-cation among school dropouts could explain the difference in exposure to sexual risk depiction between case subjects and control subjects in our study.

A history of sexual abuse was strongly associated with voluntary intercourse for girls. Our finding of sexually abused girls reporting more partners than non–sexually abused girls was similar to the results of a study in the United States.20The lack of association of sex-ual abuse with sexsex-ual initiation among boys might be attributable to the small numbers, which limited the statistical

power. The association of sexual inter-course with dropping out of school among girls but not boys might be ex-plained by girls’ greater vulnerability to adverse environmental factors.

Consistent with results of studies in the United States21 and Asia,22,23 we found associations of sexual initiation with gang activities, drinking, and smoking, with a protective role of close maternal relationships.24Unlike other studies,21we did not find peer connect-edness to be associated with sexual in-tercourse. Previous research showed that teens can influence their peers not only in initiating sex but also posi-tively in adopting more-conservative sexual norms25and delaying sexual ac-tivity.26 This could explain the similar high scores for sexually active and non–sexually active teens and thus the lack of association of peer connected-ness with sexual intercourse. Finally, our finding on the nonintention to have sex reported by a large proportion (ap-proximately one half) of adolescents who subsequently engaged in it helps us better understand why it is not practical to promote sexual absti-nence alone.

Given our finding on the strong associ-ation of pornography with adolescent sexual initiation and similar evidence of explicit sexual media from previous prospective studies,7–9 initiatives are needed to monitor, to reduce, or to re-strict access to explicit sexual media and pornography for adolescents, by working with Internet service provid-ers, parents, and the entertainment in-dustry. Parents and health care per-sonnel should communicate openly with adolescents regarding sexuality, to help the adolescents develop a more-critical attitude toward pornog-raphy.

association with exposure in the me-dia to people who have HIV/STIs or are dying as a result of AIDS, factual infor-mation about HIV and STIs, coupled with life-skills education, should be woven into television dramas to con-textualize sexual risk, so that teens can relate to it. Teens also should be taught how to resist peer pressure to engage in sex.

Young school dropouts, particularly fe-male school dropouts, should be pro-vided with out-of-school care and sex education. High-risk groups such as

those with a history of sexual abuse and those involved in smoking, drink-ing, and gang activities should be iden-tified early, for interventions on life skills and sex education.

Future research should include a lon-gitudinal study to examine over time the effects of Internet pornography and educational media on adoles-cents’ sexual initiation. Composite measures combining sexual media content from the study by Brown et al9 and media measures on sexual risk and sexual behavior from the study by

Collins et al7 should be developed to assess the effects of harmful and edu-cational sexual contents on adolescent sexual behavior.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This nonclinical trial was funded by the National Medical Research Council of Singapore.

We thank Karen Ho Kar Woon and Amy Chan Yoke Sim for their painstaking ef-forts in conducting the interviews and coordinating the survey.

REFERENCES

1. Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS; World Health Organization.2006 AIDS Epidemic Update. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS; 2007

2. Hampton T. Abstinence-only programs under fire.JAMA.2008;299(17):2013–2015

3. O’Reilly K, Medley A, Dennison J, Sweat M. Systematic review of the impact of abstinence-only programmes on risk behavior in developing countries (1990 –2005). Presented at the XVI Inter-national AIDS Conference; August 13–18, 2006; Toronto, Canada

4. Underhill K, Montgomery P, Operario D. Sexual abstinence only programmes to prevent HIV infection in high income countries: systematic review.BMJ.2007;335(7613):248 –250

5. Underhill K, Operario D, Montgomery P. Systematic review of abstinence-plus HIV prevention programs in high-income countries.PLoS Med.2007;4(9):e275

6. Kirby DB, Laris BA, Rolleri LA. Sex and HIV education programs: their impact on sexual behaviors of young people throughout the world.J Adolesc Health.2007;40(3):206 –217

7. Collins RL, Elliott MN, Berry SH, et al. Watching sex on television predicts adolescent initiation of sexual behavior.Pediatrics.2004;114(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/114/3/ e280

8. Martino SC, Collins RL, Elliott MN, Strachman A, Kanouse DE, Berry SH. Exposure to degrading versus nondegrading music lyrics and sexual behavior among youth.Pediatrics.2006;118(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/118/2/e430

9. Brown JD, L’Engle KL, Pardun CJ, Guo G, Kenneavy K, Jackson C. Sexy media matter: exposure to sexual content in music, movies, television, and magazines predicts black and white adolescents’ sexual behavior.Pediatrics.2006;117(4):1018 –1027

10. Rogala C, Tyde´n T. Does pornography influence young women’s sexual behavior?Womens Health Issues.2003;13(1):39 – 43

11. Tyde´n T, Rogala C. Sexual behaviour among young men in Sweden and the impact of pornography.

Int J STD AIDS.2004;15(9):590 –593

12. Ha¨ggstro¨m-Nordin E, Hanson U, Tyde´n T. Associations between pornography consumption and sexual practices among adolescents in Sweden.Int J STD AIDS.2005;16(2):102–107

13. Ministry of Health, Singapore. Health facts Singapore 2007. Available at: www.moh.gov.sg/ statistics.aspx?id⫽5524. Accessed January 14, 2009

14. Small SA, Luster T. Adolescent sexual activity: an ecological, risk-factor approach.J Marriage Fam.

1994;56(1):181–192

15. Jackson C, Henriksen L, Foshee VA. The Authoritative Parenting Index: predicting health risk behaviors among children and adolescents.Health Educ Behav.1998;25(3):319 –337

16. Mirande AM. Reference group theory and adolescent sexual behavior.J Marriage Fam.1968;30(4): 572–577

17. Tresidder J, Macaskill P, Bennett D, Nutbeam D. Health risk and behaviour of out-of-school 16-year-olds in New South Wales.Aust N Z J Public Health.1997;21(2):168 –174

19. Kunkel D, Biely E, Eyal K, et al.Sex on TV 3: A Biennial Report of the Kaiser Family Foundation. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2003

20. Noll JG, Trickett PK, Putnam FW. A prospective investigation of the impact of childhood sexual abuse on the development of sexuality.J Consult Clin Psychol.2003;71(3):575–586

21. Rink E, Tricker R, Harvey SM. Onset of sexual intercourse among female adolescents: the influence of perceptions, depression, and ecological factors.J Adolesc Health.2007;41(4):398 – 406 22. Liu A, Kilmarx P, Jenkins RA, et al. Sexual initiation, substance use, and sexual behavior and

knowledge among vocational students in Northern Thailand.Int Fam Plan Perspect.2006;32(3): 126 –135

23. Lee LK, Chen PC, Lee KK, Kaur J. Premarital sexual intercourse among adolescents in Malaysia: a cross-sectional Malaysian school survey.Singapore Med J.2006;47(6):476 – 481

24. Coker AL, Richter DL, Valois RF, McKeown RE, Garrison CZ, Vincent ML. Correlates and conse-quences of early initiation of sexual intercourse.J Sch Health.1994;64(9):372–377

25. Mellanby AR, Rees JB, Tripp JH. Peer-led and adult-led school health education: a critical review of available comparative research.Health Educ Res.2000;15(5):533–545

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-2954

2009;124;e44

Pediatrics

Shanta Emmanuel and George Bishop

Mee-Lian Wong, Roy Kum-Wah Chan, David Koh, Hiok-Hee Tan, Fong-Seng Lim,

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/124/1/e44

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/124/1/e44#BIBL

This article cites 20 articles, 2 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/media_sub

Media

icine_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/adolescent_health:med

Adolescent Health/Medicine

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-2954

2009;124;e44

Pediatrics

Shanta Emmanuel and George Bishop

Mee-Lian Wong, Roy Kum-Wah Chan, David Koh, Hiok-Hee Tan, Fong-Seng Lim,

Multilevel Ecological Factors

Premarital Sexual Intercourse Among Adolescents in an Asian Country:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/124/1/e44

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.