The Effectiveness of a Home Visit to Prevent Childhood Injury

W. James King, MD*; Terry P. Klassen, MD‡; John LeBlanc, MD§; Anne-Claude Bernard-Bonnin, MD

储

;

Yvonne Robitaille, PhD¶; Ba’ Pham, MSc*; Douglas Coyle, MSc#; Milton Tenenbein, MD**;

and I. Barry Pless, MD‡‡

ABSTRACT. Objective. To examine the effectiveness of a home visit program to improve home safety and decrease the frequency of injury in children. We exam-ined the effects of the program on 1) parental injury awareness and knowledge; 2) the extent that families used home safety measures; 3) the rate of injury; and 4) the cost effectiveness of the intervention.

Design. A randomized, controlled trial.

Setting. A multicenter trial conducted at 5 hospitals in 4 Canadian urban centers.

Participants. Children <8 years old, initially en-rolled in an injury case-control study, were eligible to participate.

Intervention. Subsequent to a home inspection con-ducted to determine baseline hazard rates for both groups, participants in the intervention group received a single home visit that included the provision of an formation package, discount coupons, and specific in-struction regarding home safety measures.

Main Results. The median age was 2 years, with

males comprising⬃60% of participants. The experimen-tal groups were comparable at outset in terms of case-control status, age, gender, and socioeconomic status. Parental injury awareness and knowledge was high; 73% correctly identified injury as the leading cause of death in children, and an intervention effect was not demon-strated. The adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for the home inspection items indicated that significant safety modi-fications only occurred in the number of homes having hot water not exceeding 54°C (OR: 1.31, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.14, 1.50) or the presence of a smoke detec-tor (OR: 1.45, 95% CI: 0.94, 2.22). However, the interven-tion group reported home safety modificainterven-tions of 62% at 4 months and significantly less injury visits to the doctor compared with the nonintervention group (rate ratio: 0.75; 95% CI: 0.58, 0.96). The total costs of care for injuries were significantly lower in the intervention group com-pared with the nonintervention group with a cost of $372 per injury prevented.

Conclusions. An intervention using a single home visit to improve the extent to which families use safety measures was found to be insufficient to influence the long-term adoption of home safety measures, but was effective to decrease the overall occurrence of injuries. Future programs should target a few, well-focused, evi-dence-based areas including the evaluation of high-risk groups and the effect of repeated visits on outcome.

Pediatrics 2001;108:382–388; injury, home visit, random-ized controlled trial, safety, children, cost effectiveness.

ABBREVIATIONS. ED, emergency department; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

I

njuries are the leading cause of death in

child-hood and a significant cause of morbidity.

1,2Al-though the home should be a haven of safety, for

children

⬍

15 years old, and especially for

preschool-ers, this setting represents the most frequent site of

injury occurrence.

2,3Among the most serious of

po-tential hazards are falls, suffocation, burns, and

poi-soning.

4 – 8Such injuries are numerous, not only

be-cause of increased exposure, but also bebe-cause young

children’s rapid physical development surpasses

their ability to recognize and avoid potential dangers

in their environment.

9As many injuries sustained by

children in the home are related to a lack of

appro-priate safety measures,

10 –13prevention efforts

di-rected toward the reduction of household hazards

should be implemented and evaluated.

Evidence from randomized, controlled trials

sup-ports the notion that anticipatory guidance by

phy-sicians may decrease the risk of an injury at

home.

14 –16A trial of nurse home visit services has

been shown to be effective in improving a variety of

health and social outcomes, including injury

preven-tion.

17Furthermore, a systematic review of

random-ized trials has shown that home visit program have

the potential to significantly reduce rates of child

injury.

18As such, home visits may be an important

addition to injury prevention strategies, and the role

of home visitors and nonprofessionals in the

preven-tion of child injury deserves addipreven-tional attenpreven-tion.

The present study was conducted to explore the

extent to which a home visit program would

im-prove the safety of the home environment and

de-crease the frequency of injuries. We examined the

effects of the program on 1) parental injury

aware-ness and knowledge; 2) families’ use of home safety

measures; 3) the rate of injury; and 4) the

cost-effec-tiveness of the intervention.

From the *Department of Pediatrics and Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; ‡Department of Pediatrics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Can-ada; §Department of Pediatrics, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia; 储Department of Pediatrics, University of Montreal, Montreal, Quebec, Can-ada; ¶Direction de la sante publique de Montreal-Centre, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; #Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; **Department of Pediatrics, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba; ‡‡Department of Pediatrics, McGill University, Montreal, Que-bec, Canada.

Received for publication Jun 9, 2000; accepted Feb 20, 2001.

Reprint requests to (W.J.K.) Division of Academic General Pediatrics, Chil-dren’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, 401 Smyth Rd, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1H 8L1. E-mail: king@cheo.on.ca

METHODS

This multicenter, randomized controlled trial was conducted within the context of a case-control study. The following sites participated in the trial: the Montreal Children’s Hospital, Mon-treal, Quebec, Canada; Hoˆpital Ste Justine, MonMon-treal, Quebec, Canada; IWK-Grace Health Center, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada; the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, Ontario, ada; the Winnipeg Children’s Hospital, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Can-ada. The research ethics committees of each institution approved the study protocol.

Participants

Participants⬍8 years old presenting to the emergency depart-ment (ED) of each participating center from September 1994 to October 1996, were identified using ED logs and the Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program of the Health Protection Branch, Health Canada. Children were eligible for the case-control study if they presented with 1 of the following tar-geted injuries: tap water scald; burn from a household fire; poi-soning or ingestion; choking from the ingestion of a foreign object; fracture, sprain, strain, cut, or bruise from a fall from a height; and head injury while riding a bicycle. Two controls, matched for gender and within 6 months of age, were selected for each tar-geted case. The first control was selected with a nontartar-geted injury (ie, one occurring either outside the home or a home injury not listed above). The second control was chosen from patients with a medical illness presenting to the same ED.

Intervention and Study Design

A research assistant contacted the family by telephone within 3 days of the ED visit to confirm eligibility and to arrange a home visit within 1 week. To ensure uniformity, the research assistants were trained to make a series of specific, structured observations regarding home safety hazards that included the following: ready access by children to small objects, matches, lighters, cleaning supplies, beauty supplies, medications, or electrical cords; win-dows which open easily beyond 6 inches; the absence of child resistant caps on medicines; tap water⬎54°C; the presence of a functioning smoke detector on each house level; a fire extin-guisher; safety gates at stairs; the presence of a infant walker; ease of opening basement door; the absence of certified bicycle helmets; child seat restraints; and by report only, the failure to use bicycle helmets and automobile restraints at all times. After the observa-tions were completed, the home visitor administered a question-naire regarding parental knowledge and awareness of injuries, the child’s history of past injuries requiring medical treatment, and the number of injuries involving other children in the family. After all the above measures were completed, an additional informed consent for the randomized, controlled trial was obtained from the child’s parents.

Children were randomized by the following method: an equal number of intervention and nonintervention identification cards were placed in sealed envelopes, mixed in an opaque container, sequentially numbered as they were withdrawn, and distributed in aliquots to each study site. Each home was assigned to 1 of 2 groups. Parents in the intervention group received an information package on injury prevention. The findings of the home visit were reviewed, and the family instructed on how to correct any defi-ciencies in home safety. As well, a set of coupons from a national retail store (Canadian Tire) for a $10 discount per item (to a maximum of $50) when purchasing recommended safety devices were given to each family. Finally, detailed instructions regarding each of the targeted injuries, along with demonstrations of the appropriate use of the safety device(s), were provided. This infor-mation was reinforced by follow-up telephone calls at 4 and 8 months after the initial home visit. A letter from each site’s project director stressing the need to maintain the preventive behaviors was also sent to all intervention families.

Parents of children in the nonintervention group received a general pamphlet on safety but did not receive the information package, review of the home safety findings, discount coupons, or any specific instruction regarding safety measures. One exception was the notification of families in the nonintervention group of the finding of a nonfunctioning smoke detector. All participants were contacted by telephone at 4 and 8 months, and a research assistant

blinded to the intervention assignment completed a final home visit 1 year after the initial home visit.

Sample size was calculated based on the desire to observe a 10% difference in the adoption of the home safety behaviors between the intervention groups assuming a type I error (2-sided) of 0.05 and a type II error of 0.20 (ie, statistical power of 80%). These calculations resulted in a desired sample of 375 participants in each group.19

Statistical Analysis

Participants’ characteristics, including injury awareness and knowledge, were compared between intervention groups using the Wilcoxon rank sum test for ordinal or interval scale variables and2test for categorical variables. Similarly, dropouts and

com-pleters were compared for any differences in their baseline char-acteristics. Injury knowledge and awareness were compared be-tween interventions using an analysis of variance with the dependent variable the change at 1 year expressed as a percentage of the baseline score. The analysis of variance included interven-tion, center, and their interaction. Least-square estimates of inter-vention effect were derived from the fitted models. Standard residual diagnostics were used for model goodness-of-fit.

The intervention with respect to the likelihood of adopting a given prevention strategy was compared using the desired out-comes of a reduction in potential hazards in the various home areas targeted by the intervention (eg, the hazard of choking by having small objects within children’s reach in the living room). Each outcome was analyzed separately, taking into account its baseline hazard rate, intervention, center, mechanism of injury, age, and gender using logistic regression models. Odds ratios (ORs) of intervention effects and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were derived from the fitted models. Standard residual diagnostics were used to check for goodness-of-fit of the models. Rates of injury-prone hazards were derived in the control group to aid in the interpretation of the ORs of intervention effect estimates. The extent to which the intervention decreased the frequency of injury requiring a physician visit was evaluated by comparing injury frequency between intervention groups using2test and

the ratio of injury per-person year was derived assuming a Pois-son distribution for the number of injuries.20

Economic Analysis

The objective of the economic analysis was to assess the cost-effectiveness of the intervention in terms of the incremental cost per injury prevented, therefore, all health care costs incurred as a direct result of the preventive program and all costs avoided through the reduction in injuries were estimated.21,22The cost of

the preventive program was estimated by combining the salary and infrastructure costs for the home visitors with the costs of the information packet provided to parents. The costs associated with treatment of injuries were calculated from a typical resource pro-file for each type of injury obtained from a panel of physicians. The costs of the injury treatment resources were derived from the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario cost model and from the Ontario Health Insurance Plan Schedule of Fees and Benefits. The cost model follows accepted guidelines whereby the direct costs of treatment (eg, staff, consumables) are allocated to the treatments received, while indirect costs (eg, overheads) are allocated to treatments through a simultaneous equation allocation methodol-ogy.23All costs are reported in 1999 Canadian dollars.

RESULTS Participant Characteristics

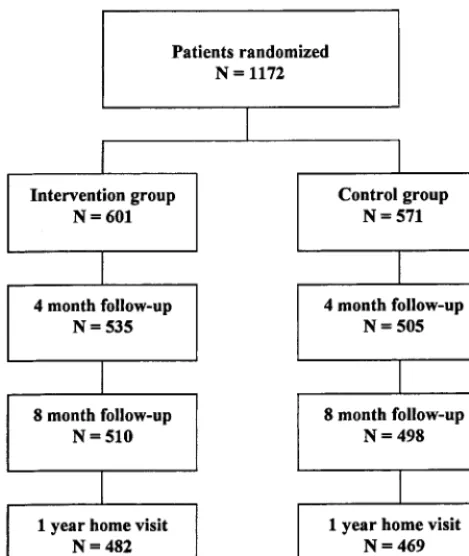

Figure 1 outlines the flow of participants from the

point of being randomized through to the last

fol-low-up contact. Baseline characteristics of the

partic-ipants are displayed in Table 1 and detailed

else-where.

24The median age in both groups was 2 years,

cor-rectly identified injury as the leading cause of death

in children

⬍

8 years old, and median scores for the

perception of accident preventability were 7 and 8

(out of 10) for the intervention and nonintervention

groups, respectively. The median score for perceived

control over decreasing accident risk was 7 (out of

10) in both groups.

Before the 1-year follow-up, 19% of randomized

participants were lost to attrition. Participants who

dropped out of the study (dropouts) had: 1)

signifi-cantly younger parents; 2) younger age at which

mother had her first child; and 3) fewer years of

minimum parental education compared with those

who completed the trial (

P

⬍

.001). Additionally,

dropouts were less likely to identify injury as the

leading cause of death (

P

⫽

.004). There were no

major differences between the dropouts randomized

to intervention (

N

⫽

118) and control (

N

⫽

103).

Table 3 indicates that there were no significant

changes in parental injury awareness and knowledge

from baseline between the intervention and control

groups. Adjusted ORs for the home inspection items

are given in Table 4, along with the baseline rates in

the control groups. Significant changes were

ob-served in the number of participant homes who had

hot water not exceeding 54 degrees centigrade (OR:

1.31; 95% CI: 1.14, 1.50) and who had smoke

detec-tors on some or all levels (OR: 1.45; 95% CI: 0.94,

2.22). However, there was no difference whether all

or some smoke detectors were fully functional (OR:

1.01; 95% CI: 0.79, 1.30). There was a significant

difference, favoring the group without intervention,

in the number of participant homes who had a fire

extinguisher (OR: 0.81; 95% CI: 0.67, 0.97). There

were no interactions between intervention and

insti-tution in any of the presented outcomes.

Intervention Effect on Injury Rate

At 4 months, participants in the intervention

group tended to report fewer injury visits to the

doctor (7%) as compared with those in the control

group (11%;

P

⬍

.05; Table 5). At the completion of

the trial, the rate of reported injury visits to the

doctor was 0.23 per patient year (95% CI: 0.19, 0.29)

for the intervention group and 0.31 per patient year

(95% CI: 0.27, 0.37) for the control group. The rate

ratio between the intervention and the control group

was 0.75 (95% CI: 0.58, 0.96). In addition, the number

of participants in the intervention group who

re-ported home safety modifications was 62% at 4

months and 23% at 8 months.

Economic Analysis

Estimates for the costs of each injury and for the

costs of the home visit program are given in Table 6.

The total cost of care for injuries was significantly

lower in the intervention group compared with the

nonintervention group ($13 481.57 compared with

$7028.25). This led to a cost per participant of $23.61

compared with $11.69. However, when allowing for

the costs of the home visit the incremental cost per

participant was $48.11. Given the reduction in the

injury rate in the intervention group the cost per

injury prevented is estimated to be $372.

DISCUSSION

This study, using a single home visit, was unable

to demonstrate effectiveness of an intervention

aimed at improving home safety modifications, but

was able to demonstrate a reduction in the rate of

injury related visits to the doctor. The potential

im-pact of this prevention strategy is substantial. For

each 12 homes visited, 1 injury visit to the doctor

would be prevented per year at an average

incre-mental cost of $372. Although this outcome looks

promising, the finding must be interpreted

cau-tiously.

The observed lack of adoption of the

recom-mended prevention may have been related to aspects

of the intervention that required action on the part of

the caregiver. The intervention, aimed primarily at

changing the environment (home) through the

pro-motion of a combination of passive and active

mea-sures, called for the simultaneous change of many

injury prevention behaviors. It is generally thought

that passive strategies, ie, those involving few

re-peated actions, are more effective than active

preven-tive strategies.

25The parental vigilance and

respon-sibility demanded by these more active measures are

notoriously difficult to motivate

26and it is possible

that the current program was not sufficient to

achieve this end.

The intervention itself may have been demanding,

making compliance difficult, although self-reports

suggest that the intervention group felt that they had

adopted safety precautions (62% and 23% reported

home safety modifications at 4 and 8 months,

respec-tively). However, actual home visit observations

found only 2 of 16 safety modifications favoring the

intervention (lowering of hot water temperature to

⬍

54° C and the presence of smoke detectors). This is

consistent with research indicating that easily

in-stalled safety devices are more likely to be used than

more difficult ones.

27A less demanding task (ie,

lowering hot water temperature) was adopted over

those safety measures that may require a greater

investment of time and energy (ie, keeping small

objects out of a child’s reach or ensuring that a bike

helmet is worn regularly). Finally, baseline

assess-ments indicated good awareness of injury risk and

preventability by parents in both groups that was

unaffected by the intervention. As such, it is likely

that families enrolled in the study were already

vig-ilant with respect to their children’s environment.

Although it is unlikely that the home visit had an

impact on the adoption of our home safety measures,

self-reports by the families suggest that they felt the

home visit was beneficial both in their perception of

TABLE 1. Participant Characteristics

All Patients (n⫽1172)

With Intervention

(n⫽601)

Without Intervention

(n⫽571)

PValue

Male-n(%) 696 (59) 352 (59) 344 (60) .56

Child’s age, y* 2 (1, 3) 2 (1, 3) 2 (1, 4) .79

Institution

Montreal Children’s Hospital 250 (21) 128 (21) 122 (21)

Hoˆpital Ste Justine 294 (25) 154 (26) 140 (25) .99

IWK-Grace Health Centre 173 (15) 88 (15) 85 (15)

Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario 300 (26) 152 (25) 148 (26) Winnipeg Children’s Hospital 155 (13) 79 (13) 76 (13) ED presentation†

Home injury,n(%) 387 (33) 193 (32) 194 (34)

Choking/asphyxiation 36 22 14

Poisoning 52 22 29

Burns and scalds 80 39 41

Falls 219 109 110

Other injuries,n(%) 389 (33) 206 (34) 183 (32)

Illnesses,n(%) 391 (34) 202 (34) 189 (34) .60

Socioeconomic status

Parent’s age, y‡ 33 (30, 37) 33 (30, 36) 33 (30, 37) .09 Age mother had first child* 27 (22, 30) 27 (23, 30) 27 (22, 30) .90 Parent’s minimum§ education*

(number of years)

13 (12, 16) 13 (12, 16) 13 (12, 16) .72

Number of siblings,n(%)

0 421 (36) 224 (37) 196 (34)

1 495 (42) 254 (42) 241 (42)

2 193 (16) 92 (16) 101 (18)

3 46 (4) 22 (4) 23 (4)

4⫹ 19 (2) 9 (1) 10 (2) .75

* Values are median (first and third quartiles.)

† Patients without a clear case-control status (N⫽5) were randomized and included in the analysis using an intent to treat principle. ‡ Average age of both parents.

§ Minimum education level from both parents.

TABLE 2. Injury Knowledge and Awareness

All Patients (n⫽1172)

With Intervention

(n⫽601)

Without Intervention

(n⫽571)

PValue

Injury knowledge,n(%)

Correctly identify injury as the leading cause of death in children younger than 8 years.

748 (73) 381 (73) 365 (73) .92

Injury awareness*

1) How often do you think injuries to children require hospital admission?†

6 (5, 7) 6 (5, 7) 6 (4, 7) .65

2) How preventable do you think most childhood injuries are?†

7 (6, 8) 7 (6, 8) 8 (7, 8) .63

3) How serious do you think most injuries are?†

5 (5, 7) 5 (5, 7) 5 (5, 7) .73

4) How much control do you think you have to decrease the risk of your child having an injury?†

7 (6, 8) 7 (6, 8) 7 (6, 8) .40

Injury history,n(%)

Have any of your children seen a doctor because of an injury in the year before the current incidence?

136 (12) 67 (13) 69 (14) .48

the adoption of home safety measures and the effect

on injury occurrence. Although it is possible that a

reporting bias accounted for the self-reported

differ-ences in injury rates, it is also likely that there is a

benefit of the home visit that we were unable to

demonstrate in this trial. The short visit (

⬍

1 hour)

may not have been sensitive enough to identify the

real change that resulted in the differential reduction

in injury occurrence. To address the issue of why the

intervention worked to decrease the rate of injury,

TABLE 3. Intervention Effectiveness Completers Only

(n⫽951)

Number of Evaluable

Patients

Baseline* % Change at Follow-up† Intervention Effect‡

P

Value§

With Intervention

(n⫽601)

Without Intervention

(n⫽567)

With Intervention

(n⫽482)

Without Intervention

(n⫽469)

Mean % Difference

(95% CI) Awareness

How often do you think injury to children require hospital admission?㛳

756 6 (5, 7) 6 (4, 7) 13.6 (6.4, 20.8) 15.2 (7.7, 22.6) ⫺1.6 (⫺11.6, 8.5) .76

How preventable do you think most children’s injuries are?㛳

792 7 (6, 8) 8 (7, 8) 7.3 (0.9, 13.7) 7.0 (0.6, 13.5) 0.3 (⫺8.5, 9.0) .95

How serious do you think most injuries are?㛳

786 5 (5, 7) 5 (5, 7) 11.6 (6.9, 16.4) 9.8 (5.0, 14.5) 1.9 (⫺4.7, 8.4) .58

How much control do you think you have to decrease the risk of your child having an injury?6㛳

790 7 (6, 8) 7 (6, 8) 3.1 (⫺1.6, 7.7) ⫺2.1 (⫺6.8, 2.6) 5.1 (⫺1.3, 11.5) .12

* Values are median (first and third quartiles).

† Least-square estimates and their 95% CIs derived from an analysis of variance with intervention, institution as independent predictors. There were no interaction between intervention and institution in any of the presented outcomes.

‡ Least-square estimates and their 95% CIs of the difference between the 2 groups: with prevention versus without prevention. § F-test of no intervention effect from the analysis of variance.

㛳Visual Analog Scale range from 0 –10 with higher value corresponding to better awareness. All percent changes were expressed as

changes relative to the baseline absolute values.

TABLE 4. Description of Injury Prevention Behaviours and Estimate of Treatment Effect Question

Number

Description Hazard Rate of Control Group

(%)

Treatment Effect (Intervention vs No Intervention)

OR (95% CI)

PValue

1 No small objects within child’s reach in the living room

19.7 1.02 (0.88, 1.18) .40

2 No matches and lighter within child’s reach in the living room

13.3 1.03 (0.85, 1.25) .40

3 No windows opened easily beyond 6 inches in the living room

50.7 1.08 (0.93, 1.25) .15

4 All household cleaning supplies are stored beyond child’s reach in the kitchen

55.6 1.04 (0.89, 1.22) .30

5 With child-resistant caps on bottles in the kitchen cupboards

49.6 0.99 (0.84, 1.16) .44

8 Hot tap water is not exceeding 54°C 46.5 1.31 (1.14, 1.50) ⬍.001 10 Smoke detectors on some or all levels 94.0 1.45 (0.94, 2.22) .05 10a All or some smoke detectors fully functional 84.0 1.01 (0.79, 1.30) .46

11 Fire extinguisher 49.5 0.81 (0.67, 0.97) .01

12 Gates at top and/or bottom of stairs 35.5 0.89 (0.71, 1.13) .17

14 Observed a baby walker 7.1 0.83 (0.49, 1.43) .25

15 Bedroom windows can not be opened beyond 6 inches

60.7 1.06 (0.92, 1.22) .22

17 No small objects within child’s reach in bedroom

16.7 0.98 (0.83, 1.16) .42

18 Bathroom cleaning supplies securely stored 55.6 0.90 (0.81, 1.19) .11 19 All or some bottles in the bathroom cupboards

have child-resistant caps

74.0 0.98 (0.81, 1.19) .42

20 Children wearing bike helmet some or all of the time

94.4 0.65 (0.31, 1.37) .13

without observed adoption of the specific prevention

strategies, we plan to contact the families to evaluate

the components of the intervention that they

per-ceived as worthwhile and those that were less

ben-eficial.

Injuries have enormous economic consequences

with an annual cost estimated at $8.7 billion in

Can-ada.

28Economic evaluation of health promotion

strategies is essential to identify interventions that

maximize health gain at the least cost to society. With

limited financial resources, prevention efforts should

focus on strategies that will yield the best benefit for

the investment. Some strategies, such as childhood

vaccines, have substantial savings in direct medical

costs for each dollar spent, whereas other strategies,

such as our intervention, may carry a net cost but still

give considerable value in return for the investment.

Previously, it has been estimated that on average,

each injury generates $4000 in direct and indirect

costs.

28Therefore, the direct care cost of $372 per

injury prevented is likely to be small in proportion to

the benefits gained by society. Also, it is important to

recognize that the cost does not include the

addi-tional direct and indirect costs of the injury (such as

the value of the time and foregone earnings of family

members who care for the injured child) and

there-fore underestimates the true economic burden to the

family and society.

Delivery of a home visit program should be as part

of a comprehensive local initiative that combines the

principle of focusing resources where they will do

the most good with that of intervening on several

risk factors simultaneously. In instances where injury

prevention initiatives have proven to be effective, the

population and/or the target behavior have been

specific and well-defined.

18,29 –33Also, successful

home visit programs are characterized by the

estab-lishment of a strong therapeutic relationship

devel-oped over frequent visits to address underlying

fac-tors associated with maternal and child health

outcomes.

34 –39Total costs of the intervention may be

reduced if the program were combined with other

home visit programs and targeted high-risk groups.

CONCLUSION

An intervention using a single home visit to

im-prove the extent to which families use passive and

active measures was insufficient to influence the

long-term adoption of home safety measures but was

effective to decrease the overall occurrence of

inju-ries. The home visit prevented 1 injury visit to the

doctor for each 12 families participating in the

pro-gram, and the cost of preventing these injuries was

small in proportion to the benefits gained by society.

Future programs should integrate with other home

visitation programs and target a few, well-focused,

evidence-based areas including the evaluation of

high-risk groups and the effect of repeated visits on

outcome.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by a grant (6605– 4290-BF) from the National Health Research and Development Program, Health and Welfare Canada.

REFERENCES

1. Rivara FP, Grossman DC, Cummings P. Injury prevention. N Engl J Med. 1992;337:543–548

2. Baker SP, O’Neill E, Ginsburg MJ, Li G.The Injury Fact Book.Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1992

3. Towner E, Dowswell T, Jarvis S. Reducing Childhood Accidents: The Effectiveness of Health Promotion Interventions: A Literature Review. Lon-don, England: Health Education Authority; 1993

4. Hall JR, Reyes HM, Horvat M, Meller JL, Stein R. The mortality of childhood falls.J Trauma. 1989;29:1273–1275

5. Lehman D, Schonfeld N. Falls from heights: a problem not just in the Northeast.Pediatrics. 1993;92:121–124

6. Feldman KW, Simms RJ. Strangulation in childhood: epidemiology and clinical course.Pediatrics. 1980;65:1079 –1085

7. McLoughlin E, Crawford JD. Burns.Pediatr Clin North Am. 1985;32: 61–75

8. Steele P, Spyker DA. Poisonings.Pediatr Clin North Am. 1985;32:77– 86 9. Pless IB.The Scientific Basis of Childhood Injury Prevention: A Review of the

TABLE 5. Outcomes From Follow-Up Interview

Phone Follow-Up At 4 Months At 8 Months At 12 Months With

Intervention

Without Intervention

With Intervention

Without Intervention

With Intervention

Without Intervention

Rate Ratio* (95% CI) Since the previous visit, have

any of your children seen a doctor because of an injury?n(%)

38 (7) 56 (11) 47 (9) 54 (11) 24 (7) 30 (9) 0.75 (0.58, 0.96)

n⫽535 n⫽505 n⫽510 n⫽498 n⫽359 n⫽343

P⫽.05† P⫽.14† P⫽.34†

Since the previous visits, have you made any change in your home to make it safer?n(%)

322 (62) 112 (23)

n⫽519 n⫽492

* Ratio of rate of injury per person-year.

† Comparisons of injury frequency between intervention groups at each time interval using2test.

TABLE 6. Costs and Use of Resource Events Resource Event Unit Cost Rate per 100

Participants Control Intervention

Abrasion $36.40 3.85 1.83

Burn $91.71 0.00 0.33

Concussion $214.33 0.35 0.00 Cut/laceration $85.82 5.60 3.33 Dental injury $86.40 0.53 0.67 Foreign body $29.70 0.53 0.33 Fracture $196.68 4.20 1.83

Hematoma $36.40 2.28 0.50

Minor head injury $67.35 3.33 0.67 Poisoning $118.2 0.70 0.33

Sprain $87.75 2.45 2.00

Other injury $98.31 1.75 0.83

Medical Literature.London, England: Child Accident Prevention Trust; 1993

10. McLoughlin E, McGuire A. The causes, cost, and prevention of child-hood burn injuries.Am J Dis Child. 1990;144:677– 683

11. Wise PH, Kotelchuck M, Wilson ML, Mills M. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in childhood mortality in Boston.N Engl J Med. 1985;313: 360 –366

12. Murdock R, Eva J. Home accidents to children under 15 years: survey of 910 cases.Br Med J. 1974;3:103–106

13. Glik DC, Greaves PE, Kronenfeld JJ, Jackson KL. Safety hazards in households with young children.J Pediatr Psychol. 1993;18:115–131 14. Bass JL, Mehta KA, Ostrovsky M, et al. Educating parents about injury

prevention.Pediatr Clin North Am. 1985;32:233–242

15. Bass JL, Christoffel KK, Widome M, et al. Childhood injury prevention counseling in primary care settings: a critical review of the literature. Pediatrics. 1993;92:544 –550

16. Clamp M, Kendrick D. A randomized controlled trial of general prac-titioner safety advice for families with children under 5 years.Br Med J. 1998;316:1576 –1579

17. Olds DL, Kitzman H. Review of research on home visiting for pregnant women and parents of young children.Future Child. 1993;3:53–92 18. Roberts I, Kramer MS, Suissa S. Does home visiting prevent childhood

injury? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials.Br Med J. 1996;312:29 –33

19. Fleiss JL.Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions.2nd ed.New York, NY: Wiley & Sons; 1981

20. Hasselblad V, McCrory DC. Meta-analytic tools for medical decision-making.Med Decis Making. 1995;15:81–96

21. Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment. Guidelines for the economic evaluation of pharmaceuticals: Canada.Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1995;11:796 –797

22. Weinstein MC, Siegel JE, Gold MR, Kamlet MS, Russell LB. Recommen-dations of the Panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine.JAMA. 1996;276:1253–1258

23. Drummond MF, O’Brien B, Stoddart GL, Torrance GS.Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes.Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1997

24. Bonnin A, Pless IB, Beaulne G, et al. Canadian collaborative study of injuries in childhood: basic results.Ambulatory Child Health. 1997;3:194

25. Haddon W. Strategy in preventive medicine: passive vs active ap-proaches to reducing human wastage.J Trauma. 1974;14:353–354 26. Baker SP. Determinants of injury and opportunities for intervention.

Am J Epidemiol. 1975;101:98 –102

27. Dershewitz RA. Will mothers use free household safety devices?Am J Dis Child. 1979;133:61– 64

28. Hygeia Group.The Economic Burden of Unintentional Injury in Canada. SMARTRISK; 1998

29. Green LW. Toward cost-benefit evaluations of health education: Some concepts, methods, and examples.Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2(suppl): 34 – 60

30. McIntire M, Angle C, Ekins B, Mofenson H, Rauber A, Schertz R. Trends in childhood poisoning: a collaborative study 1970, 1975, 1980.J Toxicol Clin Toxicol.1984;21:321–331

31. Pearn J, Nixon J. Prevention of childhood drowning accidents.Med J Australia. 1977;1:616 – 618

32. Wiseman HM, Guest K, Murray VS, Volans GN. Accidental poisoning in childhood: a multicentre survey, 1.Gen Epidemiol Hum Toxicol. 1987; 6:293–301

33. Jordan EA, Duggan AK, Hardy JB. Injuries in children of adolescent mothers: home safety education associated with decreased injury risk. Pediatrics. 1993;91:481– 487

34. Kitzman H, Olds DL, Henderson CR, et al. Effect of prenatal and infancy home visitation by nurses on pregnancy outcomes, childhood injuries, and repeated childbearing.JAMA. 1997;278:644 – 652 35. Larson CP. Efficacy of prenatal and postpartum home visits on child

health and development.Pediatrics. 1980;66:191–197

36. Olds DL, Henderson CR, Chamberlin R, Tatelbaum R. Preventing child abuse and neglect: a randomized trial of nurse home visitation. Pediat-rics. 1986;78:65–78

37. Olds DL, Henderson CR, Kitzman H. Does prenatal and infancy nurse home visitation have enduring effects on qualities of parental caregiv-ing and child health at 25 to 50 months of life.Pediatrics. 1994;93:89 –98 38. Olds DL, Henderson CR, Kitzman H, Cole R. Effects of prenatal and infancy nurse home visitation on surveillance of child maltreatment. Pediatrics. 1995;95:365–372

39. Olds DL, Kitzman H. Can home visitation improve the health of women and children at environmental risk?Pediatrics. 1990;86:108 –116

CONFIDENCE INTERVAL

Three statisticians took up duck hunting. The first fired, and his shot sailed 6

inches over the duck. Then the second fired, and his shot flew 6 inches below the

duck. At this, the third statistician excitedly exclaimed, “We got it!”

Paulos JA.A Mathematician Reads the Newspaper.New York, NY; Basic Books; 1995