____________________________________________________________________________________________________

ISSN: 2231-0614

SCIENCEDOMAIN international www.sciencedomain.org

Knowledge and Attitude of Exclusive Breastfeeding

among Hairdresser Apprentices in Ibadan, Nigeria

Zainab Olanike Akinremi

1*and Folake Olukemi Samuel

11

Department of Human Nutrition, Faculty of Public Health, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria.

Authors’ contributions

This work was carried out in collaboration between both authors. Authors ZOA and FOS were responsible for the conception and design of study, data collection, interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Article Information

DOI:10.9734/BJMMR/2015/12822

Editor(s):

(1) Crispim Cerutti Junior, Department of Social Medicine, Federal University of Espirito Santo, Brazil.

Reviewers:

(1) Anonymous, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden. (2) Anonymous, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Iran. Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history.php?iid=662&id=12&aid=6085

Received 9th July 2014 Accepted 28th August 2014 Published 13th September 2014

ABSTRACT

Aims: This study explored the knowledge and attitude concerning Exclusive Breastfeeding (EBF) among young women who are apprenticed to learn hairdressing in Agbowo community, Ibadan, Nigeria.

Study Design: The study was cross sectional in design.

Place and Duration of Study: Study was carried out in Agbowo community in Ibadan-north local government area of Ibadan, south-western Nigeria between January 2012 and June 2012.

Methodology: Through the hairdresser’s association in the study area, 164 apprentices were enumerated but only 116 met the criteria and consented to participate. Semi-structured interviewer-administered questionnaires were used to collect data on socio-demography, knowledge of EBF and attitudes towards breast feeding. Knowledge questions and attitude statements were scored and grouped as adequate or inadequate knowledge; positive or negative attitude. Association between knowledge and socio-demographic variables were explored by chi-square analysis.

Results: Most apprentices were between 21-25yrs (49%), attained the senior secondary (SSS) level of education (55.2%) and majority were single (91.4%).While many (63.8%) of the respondents had inadequate knowledge of EBF, nearly all of them (96.4%) had positive attitude to breast feeding. Only 36.23% knew that infants should receive breast milk only, 68.1% would give

water and 53.4%would give herbal teas in the first six months of life. Some misconceptions (e.g. colostrum is dirty) and negative attitudes (e.g. breast feeding inconvenient, embarrassing, sags breasts) existed. A significant association exist between age group of respondents (p=.001); level of education (p=.001) and knowledge of exclusive breast feeding.

Conclusion: Relevant interventions about EBF should focus on young people especially those with low levels of education, who have gaps in EBF knowledge so that misconceptions and negative attitudes can be resolved.

Keywords: Exclusive breast feeding; knowledge; Attitude; Apprentice; Ibadan.

1. BACKGROUND

Researchers have identified breastfeeding during the first year as one of the most important strategies for improving child survival [1-4]. Breast milk has many beneficial effects on the health of infants, especially premature and low birth weight infants. These benefits are magnified by exclusivity and breastfeeding beyond 6 months of age [3]. Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) during the first 6 months of life is an important factor for reducing infant and childhood morbidity and mortality and it is associated with a reduction in post neonatal deaths from all causes other than congenital anomalies [3]. Besides a significant reduction in acute illnesses, exclusive breastfeeding can affect the development of chronic diseases later in life [1,3]. In addition to the numerous benefits of breastfeeding for the infant, there are also various health benefits for breastfeeding mothers [4].

In line with global recommendation of the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF, the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) promote breastfeeding as the best method of feeding infants in their first year and beyond and recommend that every infant be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life, with breastfeeding continuing for up to 2 years of age or longer [5,6]. However, in Nigeria, there has been a decrease in compliance with the WHO/UNICEF recommendations for exclusively breastfeeding [7] and the rate of EBF in the country has been fluctuating. The proportion of children under the age of six months that are exclusively breastfed decreased from 17 percent in 2003 to 13 percent in 2008 [7] and 13 percent in 2010 [8] and then rose back to 17 percent in 2012 [9]; this low rates places infants at increased risk of mortality and morbidity. Despite an abundance of reasons to breastfeed, a large number of women still choose to only partially breastfeed, or to breastfeed for a short duration. Lacks of knowledge, personal beliefs and attitudes have been implicated to influence

mothers’ decision [10,11]. Attitude is defined as a bipolar concept that has a cognitive, affective and behavioral component and is a response to a stimulus [12]. Breastfeeding attitudes reflect people’s views on infant feeding [13], studies have found that positive pre-pregnancy attitudes in mothers are linked to the intention and initiation of breastfeeding [14] and also to continued breastfeeding at least four weeks postpartum [15].

Typically, apprenticeships in Nigeria are part of small businesses and are largely informal [16]. This informal sectoris divided into two broad categories namely Trading (Textile, Provisions, Cosmetics, electronics, synthetic hair and accessories, food stuffs, cooking utensils, electronics etc) and Provision of service (Hairdressing, Tailoring, Cobbler, Automobile repair, catering, barbing, carpentry, interior decoration, plumbing, painting, brick laying etc.). These apprenticeships are conducted in shops where clients are attended to, but the owners have no government recognition, registration, or support [17]. Instructors, usually a successful person in their trade, request money at inception of the training as a form of tuition, which is paid by the parents or guardians of the apprentices. Usually apprentices are within the age range of 15 to 21 years; however there are sizeable numbers of graduates of tertiary educational institutions, and older men and women who enter this apprenticeship system due to unemployment [18] or the need to acquire a skill. The duration of apprenticeship depends on level of education, age at entry [17,18] nature of trade, intensity of learning practices, age, education, learning capacity, ability of the trainee and the need of the master for the trainee’s services. The latter factor is however not usually stated during the processes of agreement [18].

[24]. There are limited published studies on workers in the informal sectors and young women in apprenticeship; much of these scant literatures revolves around HIV, Sexual and reproductive health [25-28] leaving out other medical subjects particularly with respect to Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF). This category of workers in the informal sector may not have the opportunity of acquiring enough knowledge and they may be less equipped in making informed decision about health issues including IYCF methods. Thus, their needs remain relatively neglected.

Three health structures exist in Nigeria, they include primary, secondary and tertiary institutions. Primary health care centers, PHC, are usually the first point of call for the people. They undertake minor healthcare services like malaria, fever, cold, nutrition disorders and so on; and they are especially known for health education [29]. These education include information on maternal and pregnancy matters, IYCF, immunization and family planning. These information are also available at various secondary and tertiary health institutions in the country. In Nigeria, nurses, midwifes, community health officers, pharmacy technicians, community health extension workers are the major health workers in PHC facilities. These healthcare providers are well positioned to provide adequate health information and counseling on infant feeding as a component of the services given to pregnant women during antenatal visits and they play an important educative and support role to this effect. They have been described as vanguards of information dissemination [30].

Despite the establishment and uniform distribution of PHCs in the country, an under-use of its basic health services have been reported [31]. Furthermore, pregnancy in adolescents are usually unplanned, unwanted and culturally frowned-at among various ethnic groups in Nigeria. Therefore pregnant adolescents, especially the uneducated lot, seldom seek orthodox medical counsel or attend antenatal clinics during pregnancy. Consequently, they miss out on the health and IYCF education provided at antenatal clinics and they remain boorish on this subject matter.

The current study was designed to assess the knowledge and attitude of hairdresser apprentices concerning exclusive breastfeeding and to explore some factors associated with

adequate knowledge of exclusive breastfeeding among hair dresser apprentices in Agbowo. 2. METHODS

Ibadan, the setting for the study and the capital of Oyo State, is reputed to be largest city in Africa, south of the Sahara and was the most populous city in black Africa for a long time. Contacts made with the Hairdressers’ association in Ibadan revealed that there were 16 zones out of which Agbowo was randomly selected for the study. Agbowo has many features of an urban slum: overcrowding, unplanned housing, and lack of basic social amenities such as piped water. The hairdresser’s Association in the study area was contacted, and several of their weekly meetings were attended. The purpose of the study was discussed and their support was solicited. A total of 110 shops were at that time registered with the hairdresser’s association in Agbowo, with 73 of them having apprentices ranging from 1-3 in number. A total of 164 hairdresser apprentices were enumerated in these shops. Appointments were scheduled for recruiting and interviewing the apprentice hairdressers in participating shops. The inclusion criterion was being nulliparous. The purpose of the study and the opportunity to decline was discussed, informed consent was given. All eligible and consenting apprentices available in a participating shop were included in the study. Of the 73 shops visited, 5 shops could not be included in the study due to the various reasons. Thus, a total of 116 female hairdresser apprentices who have never had any child were interviewed. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the by the University of Ibadan/ University College Hospital Institutional review board.

from the IOWA Infant Feeding Attitude scale [32]. These statements assessed convenience of breastfeeding over bottle feeding, cost, embarrassment to breastfeed in public places etc. The questionnaire was pretested among hair dresser apprentices in Iwo local government area of Osun State, which has a population of similar characteristics as the study population. The questionnaire was pretested to define its weaknesses and point out areas of correction. To enhance validity, the questionnaire was translated into Yoruba (the predominant local language in Agbowo) and back translated into English language.

Awareness and Knowledge about breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding were assessed with 31 questions of which 23 questions assessed knowledge of EBF. These 23 knowledge questions were scored and 19 was the highest score obtainable in this section. This is so because for some questions that had two parts, respondents scored a full mark if she was able to give at least one correct option in the second part of that question. Grouping of the score was based on average of the total score obtainable, i. e scores between 0-9 was grouped as inadequate knowledge while those between 10 -19 were grouped as adequate knowledge. Attitude statements were scored using the 5-point likert scale viz; 1= Strongly Agree, 2=Agree, 3=Neutral, 4=Disagree and 5=Strongly Disagree. Statements in favour of breastfeeding were reverse scored viz; 5=Strongly Agree, 4= Agree, 3=neutral, 2= Disagree and 1= strongly disagree. Data were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics from the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 15.0to obtain descriptive (means, percentages) and inferential statistics (chi-square tests), p<0.05 was taken as significant. Cross-tabulations and Pearson’s Chi-square tests was performed to assess the association of socio-demographic variables with knowledge of exclusive breastfeeding as well as the association between awareness of EBF (received any message on EBF, previous exposure to EBF) and knowledge of EBF. 3. RESULTS

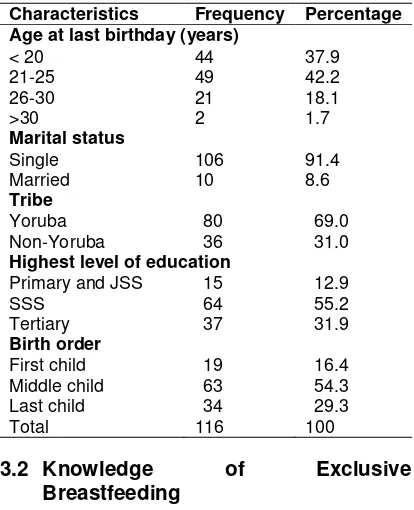

3.1 Socio Demographic Characteristics

The socio demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. The age of participants ranged from 13 to 30 with 49% being 21-25. Majority of the participants (91.4%) were single

and only 8.6% of them were married. Yoruba was the predominant e (69%). About 13% had completed 6-9 yrs of schooling having attained either primary or Junior Secondary School (JSS) education, more than half (55%) of the participants attained the Senior Secondary School (SSS) education (12 yrs of schooling), while 31.9% had tertiary education. Regarding birth order, 16.4% were first child, 54.3% were middle child and 29.3% were last child.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics

Characteristics Frequency Percentage Age at last birthday (years)

< 20 44 37.9

21-25 49 42.2

26-30 21 18.1

>30 2 1.7

Marital status

Single 106 91.4

Married 10 8.6

Tribe

Yoruba 80 69.0

Non-Yoruba 36 31.0

Highest level of education

Primary and JSS 15 12.9

SSS 64 55.2

Tertiary 37 31.9

Birth order

First child 19 16.4

Middle child 63 54.3

Last child 34 29.3

Total 116 100

3.2 Knowledge of Exclusive Breastfeeding

could mention two or more health benefits of EBF to mothers. Among those who felt infants should receive water in the first six months of life, 54.5% reported that it is necessary to quench infants’ thirst, 26.7% stated that it is essential for life and should be taken alongside breast milk. Reason for feeding infants herbal teas in the first six months of life revolved around prevention and treatment of diseases as well as maintenance of good health.

3.3 Attitude to Breastfeeding

Respondents’ attitudes towards breastfeeding are outlined in Table 3. Mean attitude score was 52.7(±7.03). Attitudes which were favourable to breastfeeding included: Breastfeeding increases mother-infant bonding (SA: 66.4%, A: 24.1%); Breastfed babies are healthier than formula fed babies (SA: 45%, A: 25.0%); Breastmilk is cheaper than formula (SA: 70.7%, A: 21.6%) and Benefits of EBF last till adulthood (SA: 24.1%, A: 12.9%).Most of the respondents (SA: 31.0%, A: 31.9%) agreed that breast feeding makes mothers breasts sag while most of them felt it would be embarrassing to breastfeed in public spaces like banks and churches but not at home. An ambivalent situation was observed regarding respondents’ attitude towards formula feeding versus breastfeeding. While most respondents disagreed that formula feeding is more convenient, it is note-worthy that a high proportion felt that formula feeding is a better choice when a mother is working.

4. GROUPING OF KNOWLEDGE AND ATTITUDES

The grouping of knowledge of respondents into adequate or inadequate, attitudes into positive or negative is presented in Table 4. After scoring, a high proportion (63.8%) of the respondents has inadequate knowledge of EBF and only few (3.4%) had negative attitudes to breastfeeding. 4.1 Factors Associated with EBF

Knowledge

Table 5 summarizes the factors associated EBF knowledge. There was a statistically significant association between knowledge of breastfeeding and (i) Age (p=0.000) (ii) Marital Status (p=0.020) (iii) Education (p=0.000) and (iv) Ethnicity (p=0.013). Knowledge of EBF increases with increased age, adequate knowledge was highest among the >30 age group while inadequate

knowledge was highest among < 20 age group. Majority (70%) of married respondents had adequate knowledge of EBF while those of single respondents had inadequate knowledge (67%). Knowledge of EBF was inadequate at all levels of education below tertiary, as majority (64.9%) of respondents with tertiary education had adequate knowledge while majority (79.7%) with

Table 2. Knowledge of Exclusive breastfeeding

Variable Frequency Percentage

Feed infants breast milk alone in the first six months of life

Yes 42 36.2

No 74 63.8

Don’t Know 0 0

Infants should receive water in the first months of life

Yes 79 68.1

No 37 31.9

Don’t Know 0 0

Feed infants liquid foods like infant formula/Cereal gruel in the first six months of life

Yes 48 41.4

No 68 58.6

Don’t Know 0 0

Feed infants herbal teas in the first six months of life

Yes 62 53.4

No 54 46.6

Don’t Know 0 0

Initiation of breastfeeding

Within 30 minutes

38 32.8

Within 1 hour 22 19.0

After 1 hour 24 20.7

Others (As soon as baby is ready)

32 27.6

Don’t Know 0 0

Feeding infants colostrum at birth

Yes 36 31.0

No 49 42.2

Don’t know 31 26.7

EBF beneficial for infants

Yes 62 53.4

No 39 33.6

Don’t know 15 12.9

EBF beneficial to mothers

Yes 23 19.8

No 70 60.3

I don’t know 23 19.8

Table 3. Attitude to breast feeding

Variable Strongly

agree %

Agree %

Neutral %

Disagree %

Strongly disagree %

Breast feeding increases mother-infant bonding.

66.4 24.1 3.4 1.7 4.3

Breast fed babies are healthier than formula fed babies

45.7 25.0 10.3 10.3 8.6

Breast milk cheaper than formula. 70.7 21.6 1.7 4.3 1.7 Benefits of EBF last till adulthood. 24.1 12.9 39.7 16.4 6.9 Breast feeding makes mothers

breasts sag.

31.0 31.9 19.0 6.9 11.2

I would be embarrassed to be seen breast feeding at home.

6.0 11.2 0.9 20.7 61.2

It’s embarrassing to be seen breast feeding in public places like banks, cafeteria, church etc

46.6 14.7 1.7 15.5 21.6

Formula feeding more convenient than breast feeding.

12.9 21.6 5.2 34.5 25.9

Formula feeding is better when mother is working

34.5 41.4 4.3 11.2 8.6

Table 4. Grouping of knowledge andof attitudes of respondents

Variable Frequency Percentage % Knowledge

Inadequate knowledge

74 63.8

Adequate knowledge

42 36.2

Attitude

Poor attitude 4 3.4

Good attitude 112 96.6

Total 116 100.0

SSS education, primary and JSS education (66.7%) had inadequate knowledge. Inadequate knowledge of EBF was common among respondents who; have never received health messages (84.9%), never received education on EBF (80.0%) and never taken care of children (80.8%). On the other hand, there was no statistically significant association between birth order and knowledge of breastfeeding (p=0.426). 5. DISCUSSION

Apprentices in this study performed especially poor in questions that examined the knowledge of exclusive breastfeeding. Some of those that knew that EBF is beneficial to infant and mother correctly mentioned the benefits while others could not. This is related to previous reports of low knowledge of EBF among mothers [33] and among adolescents and teenage primigravidae [24]. Though breast feeding culture is deeply

perceived as milk that has stayed in the breast during the nine months of pregnancy and thus become stale [37].

In the present study, findings on the use of water, cereal gruels, herbal tea and the misconception about colostrum may reflect the cultural practice of giving water in addition with breast milk by some communities in Nigeria [37], and this is hinged on some long-standing traditional beliefs and child feeding practices. Regarding knowledge of EBF, respondent were more knowledgeable about benefits to infants than benefits to mothers. If women are educated on the several health benefits of EBF to mothers, they could be increasingly motivated to practice EBF and this could be a tipping point for promoting EBF.

Table 5. Factors associated to knowledge

Factor Inadequate knowledge F (%)

Adequate knowledge

F (%)

P–value

Age at last birthday

<20 35 (79.5) 9 (20.5) .000

21-25 33 (67.3) 16 (32.7)

26-30 6 (28.6) 15 (71.4)

>30 0 (0.0) 2 (100)

Marital status

Single 71 (67.0) 35 (33.0) .020

Married 3 (30.0) 7 (70.0)

Ethnic group

Yoruba 57 (71.2) 23 (28.8) .013

Non-Yoruba 17 (47.2) 19 (52.8)

Highest level of education

Primary education JSS

10(66.7) 5 (33.3) .000

Senior Secondary School (SSS)

51 (79.7) 13 (20.3)

Tertiary Education

13 (35.1) 24 (64.9)

Birth order

First Child 10 (52.6) 9 (47.4) .426

Middle child 40 (63.5) 23 (36.5)

Last Child 24 (70.6) 10 (29.4)

Received health information/message before

Yes 29 (46.0) 34 (54.0) .000

No 45 (84.9) 8 (15.1)

Heard about/received education on EBF before

Yes 30 (49.2) 31 (50.8) .001

No 44 (80.0) 11 (20.0)

Taken care of children before

Yes 53 (58.9) 37 (41.1) .041

No 21 (80.8) 5 (19.2)

Apprentices in this study agreed that breast milk is cheaper than formula and formula feeding is

not a symbol of wealth. This is in concordance with studies of Khassawneh et al.and Zhou et al. [38,39]. Other positive attitudes exhibited include breastfeeding is more convenient than formula feeding. Similarly, Khassawneh reported that Jordanian women's positive attitude was reflected in their thinking that breastfeeding was easier than formula feeding [38]. On the other hand, respondents in the current study still regarded formula feeding as the best choice when a mother is working. This is similar to the report from a study by Zhou et al. [39] where more than half of the mothers regarded formula feeding as more convenient than breast feeding especially for a working or studying mother. Respondents believed that breast feeding makes mother’s breasts sag; this is similar to results obtained from a study on Chinese mothers in Ireland [39]. Apprentices in this study would not be embarrassed if seen breast feeding in their homes but majority of them would be embarrassed to be seen breast feeding in public places. Similarly, embarrassment and unwillingness to breastfeed in public have also been reported by other authors [39,40]. The authors opined that culture may account for this, likewise, in the present study; culture may be implicated as Nigeria cultures regard breasts as private body Parts that should not be exposed. This may hinder many people from wanting to expose their breasts in public places. That almost half of the respondents believed formula is as healthy, for infants, as breast milk cannot be unconnected with respondents’ low knowledge of EBF. Despite their low knowledge of EBF, almost all of respondents exhibited positive attitudes to breastfeeding while others exhibited negative attitudes to breastfeeding. The negative attitudes show a lack of in-depth understanding of the meaning of EBF, while the positive attitudes may be due to the fact that in the Yoruba believe system, breast feeding is regarded as a normative expectation of being a mother.

among Yoruba ethnic group may be due to misconceptions and traditional beliefs that have been reported by authors [36,37] which may hinder the acquisition of knowledge that are not aligned with these traditional beliefs.

6. CONCLUSION

Although breastfeeding is a norm in this community, apprentices in this study have low knowledge of EBF and exhibited a mixture of both positive and negative attitudes to breastfeeding. This poor performance may partly be due to lack of formal education which; hinders their ability to acquire certain information, affect exposure on matters relating to the art of breast feeding practices and impinge on their perception of certain issues as uneducated women. Misconceptions, negative attitudes and cultural belief found in this study suggest a need to focus interventions on dislodging these beliefs, and emphasize the long-term benefits of exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life.

There are no censored data about this group of women in Ibadan. However, guestimates from this study indicate that they constitute a sizeable proportion of the population of women of reproductive age, given the number of apprentices (164) enumerated within a single zone (Agbowo) which is just one of the 16 zones in Ibadan. Hence there is need to increase awareness of EBF and embark on effective interventions to improve knowledge of EBF among these group, especially those that are young, single and less educated.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The present study was reviewed and approved by the by the University of Ibadan/ University College Hospital Institutional review board. COMPETING INTERESTS

This study did not receive financial support from any individual or organization. Authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

1. Jones G, Steketee R, Black R, Bhutta Z, Morris S, The Bellagio Child Survival Study Group. Child survival II: How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet. 2003;362:65-71.

2. Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J. Child survival I: Where and why 10 million children die every year? Lancet. 2003;361:226-2234.

3. Robert E Black, Lindsay H Allen, Zulfiqar A Bhutta, Laura E Caulfield, Mercedes de Onis, Majid Ezzati, Colin Mathers, Juan Rivera. Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences. Maternal and Child Undernutrition series paper 1. Lancet 2008;371:243–60. Published Online January 17, 2008.DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0

4. United Nations Children‘s Fund (UNICEF). Infant and Young ChildFeeding Programming Guide. May 2011

5. World Health Organization. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. Geneva, Switzerland; 2003. 6. Federal Ministry of Health. National Policy

on Infant and Young Child Feeding in Nigeria; 2005.

Available:http://iycn.wpengine.netdna- cdn.com/files/National-Policy-on-Infant-and-Young-Child-Feeding-in-Nigeria.pdf 7. National Population Commission (NPC)

[Nigeria] and ICF Macro. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey; 2008.

Abuja, Nigeria.

8. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The State Of The World’s Children 2012. February 2012.

Available: www.Unicef.Org/Sowc2012. 9. National Population Commission. Nigeria

Demographic And Health Survey; 2013 (Preliminary Report).

10. Brodribb W, Fallon AB, Hegney D, O’Brien M. Identifying predictors of the reasons women give for choosing to breastfeed. J Hum Lact. 2007;23:338-344.

11. McCann MF, Baydar N, Williams RL. Breastfeeding attitudes and reported problems in a national sample of WIC participants. J Hum Lact. 2007;23:314-324. 12. Altmann TK. Attitude: a concept analysis.

Nurs Forum. 2008;43(3):144-150.

13. Sari Laanterä, Tarja Pölkki, AnetteEkström, Anna-Maija Pietilä. Breastfeeding attitudes of Finnish parents during pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2010;10:79.

Available:http://www.biomedcentral.com/14 71-2393/10/79

Ireland. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(4):561-570.

15. Mossman M, Heaman M, Dennis CL, Morris M. The influence of adolescent mothers’ breastfeeding confidence and attitudes on breastfeeding initiation and duration. J Hum Lact. 2008;24(3):268-277. 16. D. Adewole and T. Lawoyin.Characteristics

of Volunteers and Non-Volunteers for Voluntary Counseling and Testing among Male Undergraduates. African Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences. 2004;33:2:165-170.

17. Ademola J. Ajuwon, Musibau Titiloye, Frederick Oshiname, Oyediran Oyewole. Knowledge and use of HIV counseling and testing services among young persons in Ibadan, Nigeria. Int’l. Quarterly of Community Health Education. 2011;31(1):33-50. 2010-2011. © 2011, Baywood Publishing Co., Inc. doi: 10.2190/IQ.31.1.dhttp://baywood.com. 18. Egbue N.G. Gender constraints in the

training of women traders in south eastern nigeria: a case study of onitsha main market. J. Soc. Sci. 2006;12(3):163-170. 19. Ogbonna C, Okolo SN, Ezeogu A.Factors

influencing exclusive breast-feeding in Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2000;19(2):107-10.

20. Lawoyin TO, Olawuyi JF, Onadeko MO. Factors Associated With Exclusive Breastfeeding in Ibadan, Nigeria. J Hum Lact.r 2001;17(4):321-325.

doi: 10.1177/089033440101700406 . 21. Uchendu UO, Ikefuna AN, Emodi IJ.

Exclusive breastfeeding--the relationship between maternal perception and practice. Niger J Clin Pract. 2009;12(4):403.

22. Olatona FA, Odeyemi KA. Knowledge and attitude of women to exclusive breastfeeding in Ikosi District of Ikosi - Isheri Local Government Area, Lagos State. Nig Q J Hosp Med. 2011;21(1):70-4. 23. Olaolorun FM, Lawoyin TO. Health Workers’ Support for breastfeeding in Ibadan, Nigeria. J Hum Lact. 2006;22(2):188-194.

Doi:10.1177/0890334406287148

24. Ojofeitimi EO, Owolabi OO, Eni-Olorunda JT, Adesina OF, Esimai OA. Promotion of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF): The need to focus on the adolescents. Nutrition and Health. 2001;15:55. DOI: 10.1177/026010600101500107

25. Ademola J. Ajuwon, Benjamin Oladapo Olley, Iwalola Akin-Jimoh, Olagoke

Akintola. Experience of sexual coercion among adolescents in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2001;5(3):120-131. 26. Ademola J. Ajuwon, Willi McFarland,

Esther S. Hudes, Sam Adedapo, Toyin Okikiolu, Peter Lurie. HIV Risk-Related Behavior, Sexual Coercion, and Implications for Prevention Strategies among Female Apprentice Tailors, Ibadan, Nigeria. AIDS and Behavior. 2002;6(3). 27. Folashade O. Omokhodion, Kayode O.

Osungbade, Miia A. Ojannen, Noel C. Barengo. Knowledge about HIV/AIDS and Sexual practice among automobile repair workers in Ibadan, Southwest Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2007;11(2):24-32.

28. Ademola J. Ajuwon, MusibauTitiloye, Frederick Oshiname, OyediranOyewole. Knowledge and use of HIV counseling and testing services among young persons In Ibadan, Nigeria. Int’l. Quarterly of Community Health Education. 2011;31(1):33-50. Baywood Publishing Co., Inc. doi: 10.2190/IQ.31.1.d. Available: http://baywood.com

29. Isreal A. Ademiluyi, Sunday O. Aluko-Arowolo. Infrastructural distribution of healthcare services in Nigeria: An overview. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning. 2009;2(5):104-110. 30. Utoo BT, Ochejele S, Obulu MA, Utoo PM.

Breastfeeding Knowledge and Attitudes amongst Health Workers in a Health Care Facility in South-South Nigeria: the Need for Middle Level Health Manpower Development. Clinics in Mother and Child Health. 2012;9. Article ID 235565.

31. Abdulraheem IS, Olapipo AR, Amodu MO. Primary health care services in Nigeria: Critical issues and strategies for enhancing the use by the rural communities. Journal of Public Health and Epidemiology 2012;4(1):5-13. Available: http://www.academicjournals.org/JPHE 32. De La Mora A, Russell DW, Dungy CI,

Losch M, Dusdieker L: The Iowa Infant feeding attitude scale: analysis of reliability and validity. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1999;29(11):2362-2380.

33. Oche MO, Umar AS, Ahmed H. Knowledge and practice of exclusive breastfeeding in Kware, Nigeria. African Health Sciences. 2011;11(3): 518-523.

health centers: impact of baby friendly hospital initiative in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Nutr Health. 2000;14:119-125.

35. Kingsley E. Agho, Michael J. Dibley, Justice I. Odiase, Sunday M. Ogbonmwan. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2011;11:2.

Available:http://www.biomedcentral.com/14 71-2393/11/2

36. Agunbiade M. Ojo, Ogunleye V. Opeyemi. Constraints to exclusive breastfeeding practices among breastfeeding mothers in Southwest Nigeria: implication for scaling up. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2012;7:5.

Available:http://www.internationalbreastfee dingjournal.com/content/7/1/5

37. Davies–Adetugbo AA. Sociocultural factors and the promotion of exclusive breastfeeding in rural Yoruba communities of Osun State, Nigeria. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:113-125.

38. Mohammad Khassawneh, Yousef Khader, Zouhair Amarin, Ahmad Alkafajei. Knowledge, attitude and practice of breastfeeding in the north of Jordan: a cross-sectional study. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2006;1:17 doi:10.1186/1746-4358-1-17.

Available:http://www.internationalbreastfee dingjournal.com/content/1/1/17.

39. Qianling Zhou, Katherine M. Younger, John M. Kearney. An exploration of the knowledge and attitudes towards breastfeeding among a sample of Chinese mothers in Ireland. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:722.

Available:http://www.biomedcentral.com/14 71-2458/10/722

40. Kong SK, Lee DT. Factors influencing decision to breastfeed. J Adv Nurs. 2004;46(4):369-379.

© 2015 Akinremi et al.; This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Peer-review history: