Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fcpa20

Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and

Practice

ISSN: 1387-6988 (Print) 1572-5448 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fcpa20

Migrant Workers or Working Women? Comparing

Labour Supply Policies in Post-War Europe

Alexandre Afonso

To cite this article: Alexandre Afonso (2019) Migrant Workers or Working Women? Comparing Labour Supply Policies in Post-War Europe, Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 21:3, 251-269, DOI: 10.1080/13876988.2018.1527584

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2018.1527584

© 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.

Published online: 23 Oct 2018.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 890

View Crossmark data

Article

Migrant Workers or Working Women?

Comparing Labour Supply Policies in

Post-War Europe

ALEXANDRE AFONSO

Institute of Public Administration, Leiden University, The Hague, Netherlands (Received 25 February 2017; accepted 16 September 2018)

ABSTRACT Why did some European countries choose migrant labour to expand their labour force in the decades that followed World War II, while others opted for measures to expand female employment via welfare expansion? The paper argues that gender norms and the political strength of the left were important structuring factors in these choices. Female employment required a substantial expansion of state intervention (e.g. childcare; paid maternity leave). Meanwhile, migrant recruitment required minimal public investments, at least in the short term, and preserved traditional gender roles. Using the contrasting cases of Sweden and Switzerland, the article argues that the combination of a weak left (labour unions and social democratic parties) and conservative gender norms fostered the massive expansion of foreign labour and a late development of female labour force participation in Switzerland. In contrast, more progressive gender norms and a strong labour movement put an early end to guest worker programmes in Sweden, and paved the way for policies to promote female labour force participation.

Keywords:labour migration; female employment; Sweden; Switzerland; comparative public policy

Introduction

Migrant workers and women have been the two most important contributors to employment growth in industrialized countries over the last few decades (Oesch 2013). For instance, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), between 2004 and 2014 about half of the increase in the labour force in the United States, and two-thirds in Europe, could be accounted for by migrant workers (OECD2014b, p. 1). Developments in female employment have been even more far-reaching. While only 41 per cent of women were part of the labour force in OECD countries in 1960, this proportion had increased to two-thirds in 2016.1

Alexandre Afonsois an Assistant Professor at the Institute of Public Administration at Leiden University. His research focuses on labour markets, the welfare state and immigration.

Correspondence Address: Alexandre Afonso, Faculty of Governance and Global Affairs, Institute of Public Administration, Leiden University, Postbus 13228, 2501 EE The Hague, The Netherlands. Email:

a.afonso@fgga.leidenuniv.nl

This paper is part of the special issue“Social Policy by Other Means: Theorizing Unconventional Forms of Welfare Production”with guest editors Laura Seelkopf and Peter Starke

Vol. 21, No. 3, 251–269, https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2018.1527584

© 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.

In the period that followed World War II, marked by a booming economy and significant labour shortages, the timing and extent of these two developments varied significantly across countries. While Scandinavian countries raced ahead in the expansion of female employment in the 1970s, coupled with the massive expansion of social services to enable it, many Continental countries (e.g. Germany, France, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Austria) relied extensively on so-called“guest worker programmes”sourcing labour from poorer regions of the Mediterranean rim (Italy, Spain, Portugal, Morocco, Greece, Turkey). In Continental Europe, female employment progressed more slowly, before catching up in the 1990s and 2000s.

Comparing immigration and welfare state expansion as two alternative strategies to expand the labour supply, this article explore the rationales that underpinned these strategies in two countries – Sweden and Switzerland – that diverged significantly in this respect. In line with the theme of this special issue, I look at“social policy by other means”, but in contrast to other contributions focusing on how policies or actors other than conventional welfare programmes may provide social protection, I look at how immigration may act as a substitute to welfare programmes as a labour supply policy.

I argue that countries seeking to increase their labour supply could do so either by facilitating the labour market participation of women, which entailed the expansion of social services (childcare) and tax revenues, or by bringing in migrant workers, which required minimal public investment and preserved traditional gender roles. The choice between these two strategies was shaped by two factors: institutionalized gender norms, and the strength of labour unions and left-wing parties. Indeed, policies aimed at facilitating the entry of women into the labour market required not only societal norms that were favourable to female labour force participation, but also public investments in family-friendly policies, such as childcare facilities. The recruitment of foreign labour did not require such investments, at least in the short term, especially if family reunification was constrained. Using a comparison of Sweden and Switzerland, I show how power relationships and dominant gender norms structured policy choices favouring migrant labour or female employment. Conservative Switzerland relied almost exclusively on foreign labour to expand its workforce, while social democratic Sweden started drawing much earlier on female employment after an experiment with foreign labour.

The contribution of this article is embedded in the idea of“social policy by other means”, looking at the functional connections between social policies and other policy domains (Seelkopf and Starke 2018). More specifically, it links the growing literature connecting immigration, employment and welfare (Afonso and Devitt2016), and the gendered dimension of social policy (Lewis1992; Sainsbury1999). Rather than looking at alternatives to social protection, I look at another function of social policies, namely the structuring of the supply of workers in the labour market. In his seminal study, Esping-Andersen (1990, pp. 144–161) emphasized how ensuring labour market supply is an important goal of social policy, and welfare programmes can have an important effect on the employment of specific groups (Iversen and Wren1998; Sapir2006; Häusermann and Palier2008). For instance, generous early retirement schemes most likely lower participation among older workers, while childcare subsidies and care leave facilitate the labour market participation of mothers (Esping-Andersen

increase the size of the labour force in a period of high demand. This paper draws on this idea but puts it in a comparative-historical context.

Female Employment or Migrant Labour: Choices in Labour Supply Strategies

The 30 years that followed World War II were arguably the longest period of growth in Western Europe since the Industrial Revolution (Kindleberger1967; Eichengreen2008). West European economies grew at an unprecedented pace, propelled by an increasing demand for consumer goods, infrastructure and services. Technological progress allowed for remarkable jumps in productivity. Accordingly, labour markets were close to full employment. Many countries soon faced severe labour shortages. In Germany, official unemployment amongst men in September 1955 was at 1.8 per cent, meaning that nearly all of the male workforce was de facto employed (Herbert 2001, p. 202). This tight labour market resulted in growing concerns from employers and public authorities because of its inflationary tendencies. In this context, they were faced with different options: technological change; relying on the domestic labour market (e.g. women); or foreign labour (Kindleberger1967).

While the rationalization of production was a means to reduce labour demand through capital investments (Kindleberger 1967, p. 132; Eichengreen 2008, p. 6), it faced a number of limits. Replacing people with machines was not possible in every sector, especially in services. It was also limited by the availability of technology and capital. While mechanization was an important factor, I focus on choices determining which type of labour supply should be mobilized.

If an increase in demand cannot be met with technological change, one has to increase the labour supply (Von Rhein-Kress1993). Options range from increasing the working hours of the core workforce to mobilizing under-utilized sources of domestic labour, such as young people, older workers and–most importantly–women. In 1950, the proportion of women participating in the labour force was 48.5 per cent in Germany, 39.1 per cent in Switzerland, 28.8 per cent in the Netherlands, 42.9 per cent in the United Kingdom and 50 per cent in Denmark (Kindleberger1967, p. 153). An average of 14 OECD countries indicates a 45 per cent female labour force participation rate in 1965 (Brewster and Rindfuss2000).

A number of social dynamics have played out against the threefirst options (increasing working time, bringing in more young people, or more elderly people). First, given the tendency towards the reduction of working hours in the post-war period, increasing working time for the core workforce has been a difficult option for employers. Working hours have declined steadily across almost all advanced economies. Similarly, the mobi-lization of older and young (male) workers has tended to clash with the decrease in the effective retirement age after World War II,2 and the expansion of (higher) education, delaying entry into the labour market (Hagmann1966, p. 124).

Expanding the Domestic Labour Supply: Female Employment with Welfare Expansion

An obvious problem for mothers in particular was how to reconcile paid work with childcare (Morgan 2003). Enabling the labour market participation of mothers requires a particular political configuration which enables the expansion of public facilities to take care of young children and/or arrangements such as paid maternity and parental leave (Morgan2008). These policies can be understood as the translation of progressive gender norms into institutions. If this task was to be taken over by the state, it required a considerable expansion of the welfare state, and an increase in tax revenues. In this context, the expansion of female employment could face potential opposition from liberals because of itsfiscal implications, and from Christian con-servatives because of its challenge to the traditional (male-centric) family model. As I will show, Scandinavian countries were the only ones where political power relationships would prove favourable to an increase in female employment via expansion of the public sector.

Expanding the External Labour Supply: Foreign Workers

The second strategy is the import of foreign labour through temporary guest worker programmes (Kindleberger1967, p. 196; Martin and Miller1980). This strategy displayed a number of advantages. First, it seemed to be a less risky strategy to increase the labour supply in the context of uncertainty that characterized the post-war period because foreign workers possessed a higher degree of elasticity. Immigrants from poorer countries could be brought in tofill short-term labour needs, but could also–theoretically–be easily sent back to their country of origin should a new downturn arise. In this respect, it was a more secure strategy than capital-heavy technological change. Implicitly, the use of foreign labour could also help to preserve existing gender roles by making it possible to “keep native mothers at home”(Herbert2001, p. 204; Gazette de Lausanne1964).

Arguably, importing foreign labour could generate tensions within the native workforce, especially if labour migration took place concomitantly with the persistence of residual unemployment. From the point of view of trade unions, besides slowing down wage increases through an increased supply of labour, immigration also entailed the risk of the creation of a secondary labour market with worse wage and working conditions because of the presumably lower bargaining power of migrant workers, and the difficulty for unions to organize transient workers (Piore 1979). Hence, strong unions could be expected to oppose possibilities to differentiate employment terms, if not to block immigration altogether.

Explaining the Choice of Labour Supply Strategies: Gender Norms and Left-wing Power

How can we explain why certain countries put greater emphasis on female employment, while others put more on the import of foreign workers? My explanatory model is outlined inFigure 1. Each labour supply strategy entails a number of trade-offs in terms of state intervention and taxation on the one hand, and the preservation of traditional gender roles on the other. Here, I argue that gender norms and the strength of the left are important factors to explain the choice of one or the other. These factors partly overlap with differences between Bismarckian (male breadwinner) and social democratic (strong left; more egalitarian) welfare regimes, but here I disentangle their properties to delve into mechanisms.

societal values that are more favourable to gender equality and women working outside the home. Second, political power relationships which make it possible to expand state intervention. State intervention is important in terms of both the demand for and supply of female labour. One the one hand, affordable childcare makes it economically viable for mothers to work. On the other hand, the public sector (especially health, education and care) is a major employer of women: in 2011, for instance, 72 per cent of Swedish public employees were women.3Arguably, social democratic parties and trade unions need to be strong enough to allow for such an increase in state intervention.

In many ways, these conditions made it difficult to implement this strategy in Bismarckian countries. First, the traditional Bismarckian model and the Christian demo-cratic parties that shaped it were strongly anchored in the idea that women should stay at home to take care of children. Various policies and tax incentives typically discouraged female employment (Morel 2007, p. 620; Esping-Andersen 1990). Second, a central organizing logic of the Bismarckian welfare state was the principle of subsidiarity, that is, that the state should not take up tasks that can best be performed by other actors, such as the family, social partners or subnational political units. In Bismarckian systems, family policy would typically consist of cash transfers to families – essentially subsidizing families to take care of children –and little in the way of public social services (Morel

Figure1. Causal schema

2007, p. 621). In general (and with the exception of France (Morgan2003), this hindered the expansion of state intervention via public childcare services that would be required to free up the female workforce for paid employment.

Hence, foreign workers could be considered more attractive in contexts marked by a more entrenched male breadwinner model and weaker left-wing forces. By using (male) foreign labour, traditional gender norms could be preserved. The public investments required to welcome mostly young, able-bodied men into the workforce were believed to be minimal (especially if family reunification was constrained), satisfying fiscal conservatives and the principle of subsidiarity. Finally, the segmented nature of social rights in Bismarckian welfare systems was expedient to exclude them from certain benefits (Herbert2001, p. 209; Sainsbury

2012; Tabin2017). In contrast, immigration in social democratic systems was a greater risk to the preservation of an egalitarian model if it could lead to a two-tier labour market. For instance, Bucken-Knapp (2009) and Schall (2016) show that social democratic and trade union stances regarding immigration in Sweden have been guided by a desire to preserve the egalitarian Swedish social model, possibly through restrictionist measures. An important question here concerns preferences: while the preferences of social democratic parties may be less clear, labour unions can be assumed to oppose labour migration because of its potentially depressing effect on wages. If they are strong enough, they can afford to limit it, while weaker unions unable to impose restrictions on entry tend to advocate equal rights for foreign workers in order to prevent labour market segmentation (Watts2002, p. 11).

Cases and Methods

To assess my argument, I use a comparative historical analysis of welfare and immigration policy debates in Sweden and Switzerland, focusing on the 1960s. The research design is a most-similar-systems design where the main independent variables are labour strength and gender norms.4Sweden and Switzerland are appropriate cases to assess the argument insofar as they share a number of scope characteristics. They are wealthy West European countries where wage levels were large enough to be attractive for Southern European immigrants, and faced labour shortages in the 1950s and 1960s. Following Katzenstein (1985), both belong to the group of small European countries that developed corporatist structures. Both countries had remained neutral during World War II, and possessed a relatively intact production apparatus faced with a large demand for exports in the post-war period. Finally, none of them had colonial ties which could–as in the case of France, Great Britain or the Netherlands – foster immigration flows without deliberate choices guided by labour market concerns. While Sweden and Switzerland naturally exhibit idiosyncrasies, they can reasonably be considered representative of the Nordic and Continental conservative models when it comes to the power of the left and the prevalence of conservative gender norms.

can be considered a turning point: on the one hand, gender norms shifted considerably in Sweden during this period (Lundqvist2015, p. 119), while immigration was questioned (Knocke 2000, p. 163), resulting in policies to activate women. Immigration was also questioned in Switzerland in the 1960s, notably in a number of referendum votes asking for more restriction, but there was no similar movement to activate women into the workforce in response. While I focus on this period, differences persist to this day. In the Economist’s ranking of countries with the best conditions for working women in 2017, Sweden was 1st out of 29, while Switzerland was 26th.6

Figure 2shows how Switzerland and Sweden are positioned in comparison to a wider set of European countries with regard to our two independent variables of interest in the 1960s, namely left-wing power and gender norms. The figure shows clearly that Switzerland and Sweden are at the two opposites.

Regarding power relationships, these two countries have also varied starkly regarding the strength of social democratic parties. While the average share of parliamentary seats and cabinet posts held by social democratic parties between 1960 and 1980 was 47.3 per cent and 82 per cent in Sweden respectively, it was 25.6 per cent and 28 per cent in Switzerland. Even if Switzerland cannot really be taken as a“typical”conservative Bismarckian case (Obinger

Figure 2. Positioning of countries on left-wing power and gender equality indexes, 1960s

Sweden

Austria Denmark

United Kingdom

Belgium

Germany Netherlands

Switzerland

France

0 20 40 60 80

Le

ft

pow

e

ri

n

d

e

x

(1

96

0

s

)

14 19 24

Gender equality index (1960s)

Note: The two indexes are simple averages of three indicators (union density; social democratic vote share; left-wing cabinet posts) for left-left-wing strength, and two indicators (share of women in parliament; share of women in the workforce) for gender norms in the 1960s. Data comes from the CPDS dataset (Armingeon et al. 2015) and Hagmann (1966, p. 67) for the share of women in workforce.

1998) and displays strong liberal features as well, it provides a good point of comparison to Sweden with respect to two central features of the conservative model.

In order to obtain some insight into the causal mechanisms at work, for each country I carry out a comparative case study analysis of policy developments in the areas of immigration policy and female-employment-friendly social policies. The analysis is based on a variety of sources. For Switzerland, it draws on statistical sources, a newspaper analysis of the Gazette de Lausanne,Journal de Genève and theNeue Zürcher Zeitung, parliamentary debates, the yearly reports of the Swiss Employer Association, and second-ary literature. For Sweden, the analysis draws mostly on the in-depth analyses of Waara (2012) and Yalcin (2010) and other secondary sources.

Sweden: From Guest Worker Programmes to the Promotion of Female Employment

In 1947, Sweden signed itsfirst of a series of bilateral recruitment agreements with Italy and Hungary (Waara2012, p. 108). The recruitment and organization of labour migration was carried out by the newly created National Labour Market Board (AMS), a tripartite body managed by employers and trade unions. The grip of trade unions on labour migration policy was important, at least compared to the Swiss case. Local unions needed to be consulted for every work permit delivered (Knocke 2000, p. 162). Swedish unions were initially reluctant to accept labour migration as a solution to labour shortages. They emphasized the need to mobilize national unused reserves of labour, such as women, the elderly and handicapped, but without taking active measures to facilitate their entry into the labour force (Kyle1979; Yalcin2010, p. 403).7Eventually, they consented to the establish-ment of guest worker programmes (Yalcin 2010, p. 144), but made sure that labour migrationflows would not be used to undermine local wages and welfare provisions.

First, the strength of unions and their contacts with social democratic governments made sure that the opportunities for employers to differentiate employment terms and access to social benefits were limited, and rights were on a par with those of native workers. Foreign workers were allowed to change jobs within the occupational sector for which they were recruited, which, as we will see, contrasted with Switzerland. Second, foreign workers were granted access to the whole range of welfare benefits available to Swedish workers. The guarantee of an equal footing between nationals and non-nationals was laid out in the 1954 Aliens Act (Knocke2000, p. 159). Migrants were also allowed to bring in their families. Third, the recruitment agreements signed between Sweden and partner countries contained an organization clause stipulating that foreign workers com-mitted themselves to join the appropriate union for their profession, and to remain unionized during their entire stay in Sweden (Knocke 2000, p. 159). This clause was abolished in 1965, but replaced by an agreement between SAF (the main employer body) and LO (the main trade union) providing for employers to recommend joining the union. Union membership was informally understood as a precondition for migrants to obtain a job, a practice that persisted through the 1980s (Knocke 2000, p. 166).

(Knocke2000, p. 160; Borevi2014, p. 38). However, they had accepted it–providing it did not challenge wage and employment levels of Swedish workers–when faced with the fact that labour demand could only be met through a quick expansion of the workforce enabled by immigration. This tolerant stance, however, changed in the end of the 1960s. Foreign labour had increased to higher levels, especially from Yugoslavia (Knocke2000, p. 163; Waara2012, p. 41). This was also a time when LO started to envisage the existing liberal migration policy as a threat to the orderly functioning of the labour market (Knocke 2000, p. 163). First, the entry of low-skilled foreign workers could delay structural transformations that were otherwise promoted by other policies to foster productivity within the Rehn-Meidner model (Waara2012, pp. 128–129). In this model, solidaristic wage policies acted as a productivity whip on low-wage sectors. Second, it could delay the labour market participation of married women, or the wives of union members themselves.

From the 1966 Congress came a clear message. In connection to labour immigration, it was considered that the need for labour in Sweden could only be met to a small extent by the “import of foreign labour”, because most countries experienced full employment and there was a scarcity of workers everywhere. Therefore, labour shortages should be solved by creating more space for women. (Yalcin 2010, p. 145, my translation)

The same year, the labour market board AMS was given a monopoly on recruitment, and migrants coming to Sweden needed to have a work permit before entering the country. In 1967, immigrants coming on their own initiative–outside bilateral recruitment agreements –could no longer be given work permits. Eventually,in 1972, LO decided to put a stop to non-Nordic labour immigration. This did not happen through direct legislation but through an internal decision with the trade unions, which decided to systematically reject applica-tions for work permits (Yalcin 2010, pp. 155–156). It must be noted that LO explicitly justified this decision by the need to prioritize local workers, and namely women.8

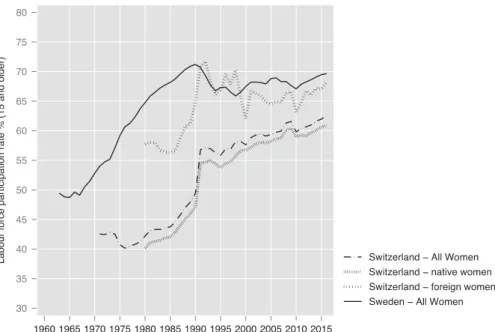

From the mid-1960s onwards, the labour force participation of women in Sweden increased very significantly, from about 50 per cent in 1968 to 70 per cent in 1989 (Figure 3). In 1965, the Swedish female participation rate was 5 per cent higher than the European average. By 1985, it had become 18 per cent higher (Brewster and Rindfuss

caring role for children”became a guiding policy theme in the 1970s (Lundqvist2015, p. 120).

Propelled by the women’s wing of LO, which had started lobbying for public childcare in the 1950s, policy proposals in the debate included the introduction of a care allowance for working mothers and the expansion of public childcare (Naumann 2005, p. 54). Towards the end of the decade, the balance would tip in favour of the expansion of childcare to promote female employment to replace guest worker policies (Naumann

2005, p. 54). From the 1960s onwards, the number of children in childcare centres increased dramatically (Nyberg2000, p. 9). A battery of policy initiatives took place to foster the labour force participation of women. These included for instance a radio programme called “The housewife changing her profession”, explaining various profes-sions available to women and how they could get the proper training to enter paid employment (Lundqvist 2015, p. 123), a plan to adapt the workplace for women, or the establishment of“activation officers”.

The background document behind these developments was a report from the National Commission on Child Care commissioned by the government to devise a strategy that could reconcile the education of children with increased female employment (Gunnarsson et al.

1999, p. 22). During the 1970s, the Swedish welfare state underwent a period of clear extension. For instance, the 1975 National Pre-School law required all municipalities to offer all six-year-olds at least 525 hours of free pre-schooling (Gunnarsson et al. 1999, p.

Figure 3. Female labour force participation rate, 15 and older, 1960–2015, Sweden and Switzerland

Note: The increase in Switzerland in 1991 is due to a different way of counting participation, lowering the th-reshold in hours worked from six hours to one hour per week. The Swiss data before this date are not completely comparable to the Swedish data.

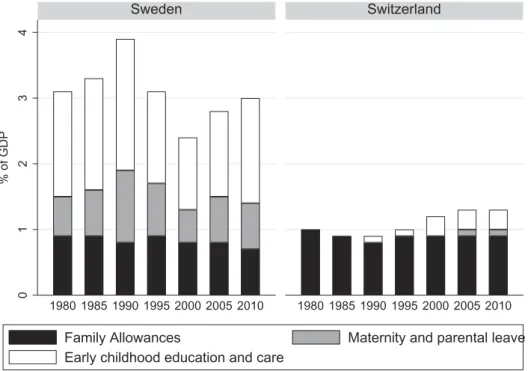

23). In 1974, paid maternal leave was substituted with paid parental leave, allowing fathers to take subsidized leave to care for their children. Nowadays, Sweden is one of the top spenders in public childcare and early education (OECD2014b) (Figure 4). In 1972, the year Sweden stopped non-Nordic labour migration, separate taxation for spouses was introduced, making it more profitable for married women to work (Knocke2000, p. 164).

Switzerland: Importing Guest Workers, Keeping Women at Home

Switzerland provides a contrasting example of labour force expansion based to a much greater extent on foreign labour than on female employment (Kindleberger 1967). The size of foreign migrationflows in Switzerland in the post-war period, in proportion to size, totally outpaced what happened in Sweden and, for that matter, almost all other West European countries (Figure 5). The context and power relationships explain a great deal of the variation in policy choices. While Sweden exhibits the typical characteristics of social democracy, Switzerland can best be characterized as a liberal-conservative model: weak and fragmented unions, the prevalence of conservative gender norms, the dominance of right-wing parties ultimately hostile to welfare expansion, and a set of political institutions (federalism, direct democracy) which prevented the emergence of a large public sector (Immergut1992; Obinger1998; Trampusch and Mach2011).

Figure 4. Public spending on family policies: family allowances, parental leave and childcare in Sweden and Switzerland, 1980–2010

0

1

2

3

4

%

of

GD

P

1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010

Sweden Switzerland

Family Allowances Maternity and parental leave Early childhood education and care

Conservative gender norms were institutionalized in a series of social policies. For instance, the 1877 law on factories prevented women from working on Sundays or at night (unlike men), but there was no compensation for income loss related to maternity. Married women were excluded from unemployment insurance between 1942 and 1951, and their benefits were set at lower rates (Tabin & Togni 2013). A constitutional article provided for paid maternity leave was adopted in 1945, but legislation to implement it was only agreed on in 2005. Up to 1995, old age pensions for married women were transferred to their husbands. The male breadwinner model was consolidated in thefirst half of the century: the share of women between 20 and 65 who worked fell from 50.7 per cent in 1910 to 42.7 per cent in 1960 (Hagmann1966, p. 66). In 1960, Switzerland had one of the lowest proportions of women in its workforce, with 29.1 per cent, compared to 34.8 per cent in Sweden, showing that in Switzerland“advocates of the woman at home have been more able to impose their rule” (Hagmann 1966, p. 67). Similarly, the proportion of women in higher education stayed stable at a very low level between 1939 and 1962 (12.9 per cent vs 13.2 per cent), while it was 40 per cent in France in 1960 (Hagmann1966, p. 67).

In the direct aftermath of the war, Swiss authorities were sceptical about the durability of post-war growth (Cerutti 2000, p. 89). In light of labour shortages in a number of economic sectors, they opted for seeking guest workers–first from Germany, then Italy– providing they would not settle. Trade unions were opposed to this measure, but the

Figure 5. Share of foreign citizens and foreign-born in Switzerland and Sweden, 1960–2015

Note: In Sweden, both data on foreign-born (who may have been naturalized) and foreign citizens is available, while only the latter is available in Switzerland. Given that high naturalization rates in Sweden make for sign-ificant discrepancies, I provide both measures.

government pursued the strategy nonetheless in light of strong employer demand (Conseil Federal 1967, pp. 73–76; Cerutti 2000, p. 89). In 1948, the Swiss government signed a bilateral agreement with Italy. In contrast to Sweden, there was no unionization clause. On the contrary, Swiss public authorities were very concerned that Italian workers could import socialist ideas with them (Cerutti2000, p. 106). The duration necessary to access permanent permits was extended from 5 to 10 years, making it more difficult to access residency status (Cerutti2000, p. 92). The explicit guidelines of immigration control were to favour temporary permits, notably seasonal permits, so that immigration could be stopped in case of a new recession. The settlement of families was also prevented, and family reunification was constrained (Cerutti2000, p. 93). The number of immigrants in Switzerland increased from 285,000 in 1950 to nearly 600,000 in 1960, and more than a million in 1970 (Piguet2005, p. 51).

Similar to Sweden, the 1960s witnessed growing concerns about the influence that immigration would have on Swiss society. However, both the nature of these concerns and the options presented to solve them were very different. First, even if trade unions were a critical voice, often calling for limitations on the recruitment of foreign labour, unlike their Swedish counterparts they yielded little influence in immigration policy making (Cattacin

1987, p. 63). The most important challengers to guest worker programmes were anti-immigration movements that threatened to use the tool of direct democracy to put an end to labour migration via a referendum;Überfremdung(“over-foreignization”) was becom-ing a growbecom-ing cause for concern.

Compared to similar debates in Sweden at the time, the most striking difference is the absence of female labour force participation as a significant potential alternative to guest worker programmes. The options discussed at the time included an increase in working time to allow for the domestic workforce to work more to compensate for a lower supply of foreign workers (Bulletin du Conseil National1965, p. 268).

its adverse impacts on the family. Third, it was believed that an increase in GDP per capita would be accompanied by a decline in female labour force participation, because families would depend less and less on this additional source of income.

During the 1960s, the government put in place a system of quotas to limit the recruitment of foreign labour. However, immigration flows continued to grow and only slowed down in the mid-1970s, because of the oil crisis (Afonso 2005). In the 1980s, labour migration resumed, and expanded further in the 2000s with the opening of the Swiss labour market to EU workers, accompanied by an extension of rights. Because most migrant workers were not covered by unemployment insurance, a large number of those who lost their jobs left the country, and unemployment did not increase in spite of a significant economic contraction (Flückiger 1992).

In contrast to Sweden, public spending on childcare remained marginal (Figure 5), and the rate of female employment, even if it was fairly close to the Swedish rate in the early 1960s, stagnated up until the mid-1980s, especially amongst Swiss women; migrant women displayed a much higher activity rate (Figure 4). The policy activism witnessed in Sweden was absent in Switzerland; a major stumbling block was federalism, cantons being responsible for education and childcare. By any standard, Swiss family policies, and especially policies aimed at supporting working mothers, lagged behind most neighbour-ing countries (Kuebler2007, p. 217) (Figure 5). For most of the twentieth century, state-sponsored family policies in Switzerland have been limited to family allowances intro-duced in all cantons during the 1950s and 1960s (Kuebler2007, p. 219) (Figure 5). But while family allowances could be reconciled with a traditional single-earner family model, attempts at welfare schemes which could facilitate a more balanced participation of women on the labour market repeatedly failed. While a constitutional article providing for publicly paid maternity leave was accepted in 1945, it only materialized in actual legislation 60 years later (Häusermann 2010). In 1964, the government rejected the introduction of paid maternity leave in health insurance provisions (Kuebler 2007, p. 219), and another attempt supported by the women’s movement was voted down in a referendum in 1984.

In 1964, a trade unionist cited in theGazette de Lausannecriticized“daycare centres, school meals and other measures allowing women to escape their primary duties and integrate in economic processes” (Gazette de Lausanne 1964). Trade unions were also opposed to the expansion of part-time work, which they thought was not an appropriate measure to reduce the demand for foreign workers, and could constitute unfair competi-tion (Journal1965). In a study of foreign labour in Switzerland, Hagmann (1966, p. 123) was more optimistic about the prospect of an increase in female labour force participation, mostly through the channel of part-time work, but it would have to face the opposition of trade unions seeing part-time work as a form of unfair competition, and employers worried about problems of organization. Regarding an increase in state intervention to fund paid maternity leave, the strength of employers and right-wing parties constituted a stumbling block, as they consistently opposed funding welfare schemes to help women reconcile work and family. As late as 1997, the President of the Swiss Employers’Union, the main employer body, declared in an interview that

can prepare for it, you can do it when you can afford it. It’s always what we have said with my wife . . . She made the choice of staying at home. But we have waited to have enough money to have our first child. For instance, we waited to buy a car. [Asked whether current policies require a choice between maternity and paid employment] Some psychologists say that the presence of the mother with the children is actually a good thing. (Le Nouveau Quotidien, 19 June 1997, p. 7, my translation)

Hence, state intervention to promote the reconciliation of family and working life was not considered a policy priority as in Sweden, because it would challenge deeply entrenched traditional gender roles, but would also entail a significant expansion of the state that dominant right-wing parties (particularly Christian democrats and liberals) and employers were not ready to accept until recently (Kuebler2007, p. 225).

Conclusion

In this article, I have compared Switzerland and Sweden to show how the interaction between left-wing power and gender norms led to different strategies to expand the labour force. In this context, guest worker programmes emerged as an expedient complement to the conservative Swiss welfare regime, as it allowed the labour supply to expand at a relatively low cost, without expanding welfare programmes – and therefore taxation – and without challenging deeply entrenched gender norms. This took place in a context of weak power resources of the left both in the parliamentary and corporatist arena, and the delayed extension of suffrage to women. In Sweden, guest worker programmes were seen as a challenge to the Swedish social welfare model, and the expansion of female employment via employment-friendly welfare programmes was fostered by a more favourable set of power relationships. Female employment had already been higher, strong trade unions and social democrats in power were favourable to an expansion of state intervention.

A number of limits and options for further research can be outlined. First, it could be argued that female and (mostly male) migrant employment are not completely interchangeable, and that the available labour supply strategies could be dictated by different sectoral setups of the economy. Indeed, the largest receivers of foreign labour in Switzerland in the 1950s and 1960s were construction and metallurgy, two sectors with a very pronounced male gender bias. In contrast, the take-off in female employment in Sweden from the 1960s onwards was underpinned by the expansion of public health and social services, where the gender balance tips towards women. In this context, it is unclear whether these developments are aconsequenceof different labour supply strategies, because the labour supply can also strongly shape the patterns of expansion of economic sectors (Wright and Dwyer 2003), or acause, assuming that the sectoral demand for employment in the economy is exogenous. Further research should seek to address this potential issue of reverse causality (see also Oesch2013).

The second question is the external validity of the findings presented here based on two countries. If Switzerland may be the clearest case of labour expansion via guest worker programmes, these also played an important role in other Bismarckian countries such as France (Weil 1995), Germany (Herbert 2001) or the Netherlands (Penninx and Roosblad

to establish the scope conditions of the mechanisms outlined here. Typically, other Continental countries displayed lower employment rates, while both Sweden and Switzerland achieved high employment levels through different routes. The temporal focus should also be specified, as there seems to have been a significant convergence in level of both immigration and female employ-ment from the 1990s onwards. The important mechanism underpinning female employemploy-ment in Switzerland has been part-time work (Afonso and Visser2014), while immigration to Sweden in recent decades has mainly taken place via the channel of asylum.

Drawing on the present analysis, an important future research agenda will consist in examin-ing the different ways whereby immigration can pursue social policy goals by other means in both sending and receiving countries. While I have focussed on the labour supply function of social policy, in some countries migrant workers deliver private services (childcare; elderly care) that are not adequately provided by the state (Sciortino2004; Van Hooren2012). In sending countries, remittances sent by emigrants can act as an insurance mechanism equivalent to social spending, potentially dampening demand for “conventional” social policies (Doyle 2015). Hence, immigration constitutes a promising focus to explore how social policy goals can be pursued by other means.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank many anonymous reviewers, Laura Seelkopf, Peter Starke, Tim Dorlach, Hendrik Moeys, Santiago Lopez Cariboni, Natascha van der Zwan, Andrei Poama, Toon Kerkhoff and Sarah Giest for very useful comments and suggestions on previous versions of this paper.

Notes

1. OECD Labour Force Statistics.

2. While the average age of retirement in OECD countries was 68.2 years in 1970, it fallen declined to 63 in 2004, before starting another increase after that.

3. In this sense, it can also be argued that facilitating female employment implies choices in terms of industrial development. Getting more women into the workforce fosters the (public) services sector, while (male) migrants fosters private industry.

4. While this research design may be considered indeterminate because it assesses the impact of two indepen-dent variables in two cases, I am primarily interested in the interactions between these two indepenindepen-dent variables. Moreover, using process tracing allows us to compensate to some extent for this problem. Ideally, a four-country comparison could be carried out to obtain variation in the two independent variables. France could be a case of progressive gender norms with a weak labour movement, and Austria could be a case with a strong labour movement and conservative gender norms.

5. While it is difficult tofind data on attitudes going far back in time, data from the World Values Survey in 1996 point to the differences between Switzerland and Sweden: Swedish respondents were significantly more likely to disagree with the idea that jobs should be reserved for men when jobs are scarce (90.5 per cent opposed) than Swiss respondents (54.6 per cent opposed). We can assume that this percentage was much higher in previous decades.

6. https://www.economist.com/news/business/21737078-america-rises-ranking-germany-falls-and-metoo-move ment-makes-its-mark-south.

7. Yalcin (2010, p. 403) argues that the emphasis on women in the 1950s was just a rethorical strategy, and that LO had no real interest in expanding the labour force: labour shortages meant rising wages.

ORCID

Alexandre Afonso http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3545-5035

References

Afonso, A., 2005, When the export of social problems is no longer possible: immigration policies and unemployment in Switzerland.Social Policy & Administration,39, pp. 653–668.

Afonso, A. and Devitt, C.,2016, Comparative political economy and international migration.Socio-Economic Review,14, pp. 591–613.

Afonso, A. and Visser, J.,2014, The liberal road to high employment and low inequality? The Dutch and Swiss social models in the crisis, in: A. Martin and J.-E. Dolvik (Eds)European Social Models from Crisis to Crisis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 214–245.

Borevi, K., 2014, Sweden: the flagship of multiculturalism, in: G. Brochmann and A. Hagelund (Eds)Immigration Policy and the Scandinavian Welfare State 1945-2010. Basingstoke: Palgrave, pp. 25–97. Brewster, K. L. and Rindfuss, R. R.,2000, Fertility and women’s employment in industrialized nations,Annual

Review of Sociology,26, 271–296.

Bucken-Knapp, G.,2009,Defending the Swedish Model. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Bulletin du Conseil National,1965, Session de Printemps, Postulat Bärlocher. Abbau des Fremdarbeiterbestandes durch Rationalisierung und Verlängerung der Arbeitszeit, 257–275.

Cattacin, S.,1987,Neokorporatismus in Der Schweiz: die Fremdarbeiterpolitik. Zürich: Forschungsstelle für Politische Wissenschaft.

Cerutti, M.,2000, La Politique Migratoire de la Suisse 1945–1970, in: H. Mahnig and S. Cattacin (Eds)Histoire De La Politique De Migration, D’Asile Et D’Intégration En Suisse Depuis 1948. Research Report for the Swiss National Fund for Scientific Research. Zurich: Seismo, pp. 89–134.

Conseil Federal,1965, Rapport Du Conseil Fédéral À la Commission Élargie Des Affaires Étrangères Du Conseil National sur la Limitation et la Réduction de L’Effectif de Travailleurs Étrangers.Feuille Fédérale,1965, pp. 334–360. Conseil, F. 1967 “Rapport du Conseil fédéral à l’Assemblée fédérale sur l’initiative populaire contre la

pénétration étrangère”, Feuille Fédérale, 33.

Devitt, C.,2015, Mothers or migrants? Labour supply policies in Ireland 1997–2007,Social Politics,23, pp. 214–238.

Doyle, D.,2015, Remittances and Social Spending.American Political Science Review,109(4), pp. 785–802. Eichengreen, B.,2008,The European Economy Since 1945. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Esping-Andersen, G.,1990,The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Flückiger, Y.,1992, La Politique Suisse En Matière D’Immigration, in: B. Beat (Ed)Main D’Oeuvre Étrangère: une Analyse de L’Économie Suisse. Paris: Economica, pp. 17–26.

Gazette de Lausanne,1964, « Une solution pour pallier à la pénurie de main d’oeuvre: Le Travail à Temps Partiel », 30 October 1964, p. 3.

Gunnarsson, L., Korpi, B. M. and Nordenstam, U.1999.Early Childhood Education and Care Policy in Sweden: Background Report Prepared for the Oecd Thematic Review. Ministry of Education and Science in Sweden Hagmann, H.-M.,1966,Les travailleurs étrangers.Chance et Tourment de la Suisse. Lausanne: Payot. Häusermann, S.,2010, Reform opportunities in a Bismarckian Latecomer: restructuring the Swiss welfare state,

in: B. Palier (Ed)A Long Good-Bye to Bismarck? the Politics of Welfare Reform in Continental Europe. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 207–232.

Häusermann, S. and Palier, B.,2008, The politics of employment-friendly welfare reforms in post-industrial economies.Socio-Economic Review,6, pp. 559–586.

Huber, K.,1963,Die ausländischen Arbeitskräfte in der Schweiz.Solothurn: Vogt-Schild. Herbert, U.,2001,Geschichte Der Ausländerpolitik in Deutschland. Munich: C.H Beck.

Immergut, E. M.,1992,Health Politics: interests and Institutions in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Iversen, T. and Wren, A.,1998, Equality, employment, and budgetary restraint: the trilemma of the service economy.World Politics,50, pp. 507–546.

Journal, D. G.,1965, Le Travail des Femmes à Temps Partiel, 28 April 1965, p. 17.

Kindleberger, C. P., 1967, Europe’s Postwar Growth: the Role of Labour Supply. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Knocke, W.,2000, Sweden: insiders outside the trade union mainstream, in: R. Penninx and J. Roosblad (Eds) Trade Unions, Immigration, and Immigrants in Europe, 1960-1993: A Comparative Study of the Attitudes and Actions of Trade Unions in Seven West European Countries. New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 157–182. Kuebler, D.,2007, Understanding the recent expansion of Swiss family policy: an idea-centred approach.Journal

of Social Policy,36, pp. 217–237.

Kyle, G.,1979,Gästarbeterska I Mansamhället. Stockholm: Liberförlag.

Lewis, J.,1992, Gender and the development of welfare regimes.Journal of European Social Policy,2, pp. 159–173. Lundqvist, A.,2015, Activating women in the Swedish model.Social Politics,22, pp. 111–132.

Martin, P. L. and Miller, M. J., 1980, Guestworkers: lessons from Western Europe. Industrial and Labor Relations Review,33, pp. 315–330.

Morel, N.,2007, From subsidiarity to‘free choice’: child and elder care policy reforms in France, Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands.Social Policy & Administration,41, pp. 618–637.

Morgan, K.,2003, The politics of mothers’employment: France in comparative perspective.World Politics,55 (2), pp. 259–289.

Morgan, K. J.,2008, The political path to a dual earner/dual carer society: pitfalls and possibilities.Politics & Society,36(3), pp. 403–420.

Naumann, I. K.,2005, Child care and feminism in West Germany and Sweden in the 1960s and 1970s.Journal of European Social Policy,15, pp. 47–63.

Nyberg, A.,2000, From Foster mothers to child care centers: a history of working mothers and child care in Sweden.Feminist Economics,6, pp. 5–20.

Obinger, H., 1998, Federalism, direct democracy, and welfare state development in Switzerland.Journal of Public Policy,18, pp. 241–263.

OECD, 2014a,Pf3.1: public Spending on Childcare and Early Education. Paris: OECD.

OECD,2014b,Is Migration Good or Bad for the Economy?Paris: OECD Migration Policy Debates. Oesch, D.,2013,Occupational Change in Europe: how Technology and Education Transform the Job Structure.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

OFIAMT,1964,Le Problème de la Main D’Oeuvre Étrangère. Bern: OFIAMT.

Penninx, R. and Roosblad, J.,2000,Trade Unions, Immigration, and Immigrants in Europe, 1960-1993: A Comparative Study of the Attitudes and Actions of Trade Unions in Seven West European Countries. New York: Berghahn Books.

Piguet, E., 2005, L’immigration En Suisse Depuis 1948 - Contexte et Conséquences Des Politiques D’immigration, D’intégration et D’asile, in H. Mahnig (Ed)Histoire de la Politique de Migration, D’aile et D’intégration Depuis 1948. Zurich: Seismo, pp. 37–63.

Piore, M.,1979,Birds of Passage: migrant Labour and Industrial Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Sainsbury, D.,1999,Gender and Welfare State Regimes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sainsbury, D., 2012, Welfare States and Immigrant Rights: the Politics of Inclusion and Exclusion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sapir, A.,2006, Globalization and the reform of European social models*.JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies,44, pp. 369–390.

Schall, C. E.,2016,The Rise and Fall of the Miraculous Welfare Machine: immigration and Social Democracy in Twentieth-Century Sweden. Ithaca: Cornell/ILR Press.

Sciortino, G., 2004, Immigration in a Mediterranean welfare state: the Italian experience in comparative perspective.Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice,6, pp. 111–129.

Seelkopf, L. and Starke, P.,2018, Social policy by other means: theorising unconventional forms of welfare production,Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis.

Tabin, J. P.,2017, Quand l’Etat social profite des immigrés, Revue d’Information Sociale,https://www.reiso.org/ articles/themes/migrations/1755-quand-l-etat-social-profite-des-immigres.

Tabin, J. P. and Togni, C.,2013,L’Assurance-Chomage En Suisse. Lausanne: Antipodes.

Trampusch, C. and Mach, A., eds,2011,Switzerland in Europe: continuity and Change in the Swiss Political Economy. London: Routledge.

Van Hooren, F. J.,2012, Varieties of migrant care work: comparing patterns of migrant labour in social care. Journal of European Social Policy,22, pp. 133–147.

Von Rhein-Kress, G.,1993, Coping with economic crisis: labour supply as a policy instrument, in F. G. Castles (Ed)Families of Nations. Dartmouth: Brookfield, pp. 131–178.

Waara, J. 2012.Svenska Arbetsgivareföreningen Och Arbetskraftsinvandringen 1945-1972. Gothenburg: PhD Dissertation.

Watts, J., 2002,Immigration Policy and the Challenge of Globalization: unions and Employers in Unlikely Alliance. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Weil, P.,1995,La France et Ses Étrangers: L’Aventure D’Une Politique de L’Immigration de 1938 À Nos Jours. Paris: Gallimard.

Wright, E. O. and Dwyer, R. E.,2003, The patterns of job expansions in the USA: a comparison of the 1960s and 1990s.Socio-Economic Review,1, pp. 289–325.