Original Article

Clinical pathways combined with

psychological intervention nursing

model for patients with ovarian cancer

Jiangrong Yang, Yongyan Ding

Jingzhou Central Hospital, Jingzhou, Hubei, China

Received July 7, 2019; Accepted September 3, 2019; Epub October 15, 2019; Published October 30, 2019

Abstract: Objective: The aim of the current study was to explore the application of clinical pathways combined with psychological intervention for patients with ovarian cancer. Methods: A total of 126 patients with ovarian cancer were randomly divided into the observation group and control group. Sixty-three patients in the control group were given routine nursing, while 63 patients in the observation group were given clinical pathways combined with psy-chological intervention. Various parameters were recorded, including Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) scores, nursing satisfaction scores, and quality of life scores measured by the ovarian

cancer patient specific scale (FACT-B). Results: SAS scores of the observation group, after nursing, were significantly

lower than those of the control group after nursing (P<0.001). SDS scores of the two groups, after nursing, were

sig-nificantly lower than those before nursing (P<0.001). Nursing satisfaction, general satisfaction, and total satisfac

-tion scores of patients in the observa-tion group were significantly higher than those in the control group (P<0.001). Physical status, social and family status, emotional status, functional status, and ovarian cancer specific module scores of the observation group, after nursing, were significantly higher than those of the control group (P<0.001).

Conclusion: Application of clinical pathways combined with psychological intervention in patients with ovarian can-cer can effectively improve bad moods and raise quality of life scores.

Keywords: Clinical pathways, psychological intervention, nursing model, ovarian cancer

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is a kind of female malignant tumor with very high incidence rates. Early symptoms of ovarian cancer are not obvious, seriously affecting the prognosis and survival of patients [1, 2]. Worldwide incidence and mortality rates of ovarian cancer are very high, seriously threatening the lives and health of women [3]. Ovarian cancer usually has a higher cure rate in the early stages. However, because of the small ovarian volume and in- sidious onset of early ovarian cancer, most cases have spread to advanced cancer when

ovarian cancer is finally detected [4, 5].

Rese-ction of ovarian cancer is a common method in clinical treatment. However, the physical and psychological pain caused by resection proce-dures has a great impact on women’s health [5, 6]. Therefore, it is a key point in nursing for

patients with ovarian cancer to carry out better psychological intervention.

The routine nursing model is nursing interven-tion for patients through environmental, medi-cation, and other aspects. However, the quality of nursing is limited [7]. Compared with the routine nursing model, clinical nursing path-ways are based on routine environment and medication, combined with clinical status,

for-mulating a scientific nursing plan for patients.

can-cer. Thus, it is an effective intervention in improving the mental and emotional states of patients [11]. Currently, there are no studies centered on clinical pathways combined with psychological intervention for ovarian cancer patients. Therefore, the current study aimed to explore a more reasonable nursing method for patients with ovarian cancer.

Material and methods

General data

A total of 126 patients with ovarian cancer were randomly divided into the observation group and control group. Sixty-three patients in the control group were given the routine nurs-ing model of ovarian cancer, while 63 pa- tients in the observation group were given clini-cal pathways combined with psychologiclini-cal intervention.

Inclusion criteria: Patients met international ovarian cancer diagnostic criteria [13]; Dia-

gnosis was confirmed by pathological biopsy

and imaging examinations.

Exclusion criteria: Subjects with neurological diseases, liver dysfunction, renal dysfunction, and severe organ function diseases; Patients with serious complications during treatment and pregnant women.

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Central Hospital. All patients and families provided informed consent in advance. Nursing methods

Patients in the control group received routine nursing, beginning from admission to 3 months after discharge. The relevant medical staff monitors vital signs, treatment methods, and recoveries of patients. They adjust nursing methods according to the actual situations of patients. The relevant medical staff strictly fol-lows the doctor’s advice, uniformly administer-ing drugs to patients.

The observation group was treated with psy-chological intervention combined with clinical pathways within the same time period as the control group. A clinical pathways group is established by doctors and nurses. When the patient is admitted to the hospital, medical staffs in this group develop a nursing plan,

understanding the patient’s basic conditions and nursing needs. (1) Clinical pathways nurs-ing: Relevant nursing staff members adjust the nursing content according to different condi-tions of different patients. They introduce the considerations, times, and processes of surgi-cal treatment to patients and their relatives before the operation. They also observe the physical indicators of patients, such as blood and liquid infusion, wound healing, urination, and other conditions after the operation. The staff gives corresponding discharge and life guidance to patients, explaining the impor-tance of a healthy lifestyle in improving the conditions of patients. They remind patients to keep a regular routine in daily life, avoiding staying up late and avoiding greasy foods; (2) Psychological intervention: The nursing staff often communicates with patients and their relatives, patiently explaining occurrence, de- velopment, and prognosis of ovarian cancer. When listening to patient emotions, the nursing staff members maintain a kind attitude and use patient words, comforting the patients.

They can enhance patient confidence in treat -ment by suggestive language. Some successful cases of treatment are appropriately discussed, eliminating patient anxiety, depression, and mental burdens. After the patient is discharged from the hospital, they communicate with the hospital through social apps or social networks. Additionally, home nursing is implemented according to the program issued by the hospital.

Evaluation standards

rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) [13] and Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) [14] scores were used to compare the emotional improvement of patients before and after 3 months of nursing. Post-nursing quality of life was determined by

ovarian cancer patient specific scale (FACT-B)

scores, a 44-item self-report instrument de- signed to measure multidimensional quality of life [15]. Nursing satisfaction was assessed with questionnaires that measure patient per-ception of services received. Higher scores indicate higher quality of life and satisfaction levels.

Outcome measures

satisfaction scores of ovarian cancer patients in the two groups were compared. Quality of life of ovarian cancer patients in the two groups

was compared using FACT-B scores.

Statistical methods

SPSS 17.0 (Beijing STRONG VINDA Information

Technology Co., Ltd.) software system was used for statistical analysis. Enumeration data are expressed by [n (%)]. Comparisons between the observation group and control group were per-formed by X2 tests. Measurement data are expressed by mean ± standard deviation. Comparisons between the observation group and control group were performed by indepen-dent sample t-tests, while comparisons before and after nursing within the same group were performed by paired t-tests. P<0.05 indicates

that differences are statistically significant.

Results

General clinical data of the two groups

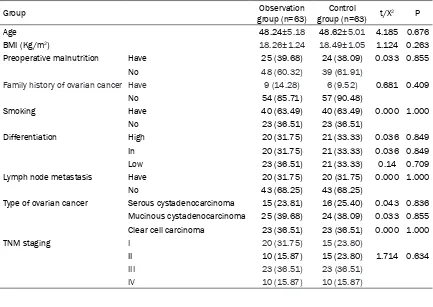

There were no significant differences in age,

[image:3.612.90.523.84.391.2]family history of ovarian cancer, smoking, dif-ferentiation, lymph node metastasis, and types of ovarian cancer between the two groups (P>0.05, Table 1).

Table 1. General clinical data of patients in the two groups

Group group (n=63)Observation group (n=63)Control t/X2 P

Age 48.24±5.18 48.62±5.01 4.185 0.676

BMI (Kg/m2) 18.26±1.24 18.49±1.05 1.124 0.263

Preoperative malnutrition Have 25 (39.68) 24 (38.09) 0.033 0.855

No 48 (60.32) 39 (61.91)

Family history of ovarian cancer Have 9 (14.28) 6 (9.52) 0.681 0.409

No 54 (85.71) 57 (90.48)

Smoking Have 40 (63.49) 40 (63.49) 0.000 1.000

No 23 (36.51) 23 (36.51)

Differentiation High 20 (31.75) 21 (33.33) 0.036 0.849

In 20 (31.75) 21 (33.33) 0.036 0.849

Low 23 (36.51) 21 (33.33) 0.14 0.709

Lymph node metastasis Have 20 (31.75) 20 (31.75) 0.000 1.000

No 43 (68.25) 43 (68.25)

Type of ovarian cancer Serous cystadenocarcinoma 15 (23.81) 16 (25.40) 0.043 0.836 Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma 25 (39.68) 24 (38.09) 0.033 0.855 Clear cell carcinoma 23 (36.51) 23 (36.51) 0.000 1.000

TNM staging I 20 (31.75) 15 (23.80)

II 10 (15.87) 15 (23.80) 1.714 0.634

III 23 (36.51) 23 (36.51)

IV 10 (15.87) 10 (15.87)

Figure 1. Comparison of SAS score between observa-tion group and control group before and after nurs-ing. *indicates that SAS scores of the two groups

af-ter nursing were significantly lower than those before nursing and that differences are statistically signifi -cant (P<0.001). #indicates that SAS scores of the

ob-servation group after nursing were significantly lower

than those of the control group after nursing and that

differences are statistically significant (P<0.001).

Comparison of SAS scores between the ob-servation group and control group before and after nursing

SAS scores of the observation group, before and after nursing, were (48.22±2.85) and (35.05±2.17), respectively. SAS scores of the control group, before and after nursing, were (48.09±3.14) and (44.89±2.13) respectively. SAS scores of the two groups, after nursing,

were significantly lower than those before nurs -ing (P<0.001). Present results showed no

sig-SDS scores of the observation group, before and after nursing, were (47.69±3.54) and (34.01±1.66), respectively. SDS scores of the control group, before and after nursing, were (47.18±3.23) and (41.14±2.19), respectively. SDS scores of the two groups, after nursing,

were significantly lower than those before nurs

-ing (P<0.001). Results showed no significant

differences in SDS scores between the obser-vation group and control group before nursing (P>0.05), while SDS scores of the observation

group, after nursing, were significantly lower

than those of the control group after nursing (P<0.001) (Figure 2 and Table 3).

Comparison of nursing satisfaction between the observation group and control group

Nursing satisfaction, general satisfaction, and total satisfaction scores of patients in the ob-

servation group were significantly higher than

those in the control group (P<0.001). Nursing dissatisfaction of patients in the observation

group was significantly lower than that of the

control group (P<0.001) (Table 4).

Comparison of quality of life scores between the observation group and control group after nursing

Physical status, social and family status, emo-tional status, funcemo-tional status, and ovarian

cancer specific module scores of patients

in the observation group, after nursing, we- re (19.47±5.02), (25.37±2.84), (19.26±3.10), (11.59±1.94), and (23.18±2.18). Physical sta-tus, social and family stasta-tus, emotional stasta-tus,

functional status, and ovarian cancer specific

[image:4.612.90.359.98.175.2]module scores of patients in the control gro- up, after nursing, were (13.16±3.05), (16.34± 2.90), (13.54±1.69), (8.26±1.88), and (16.28± Table 2. Comparison of SAS scores before and after nursing

between the two groups

Group group (n=63)Observation group (n=63)Control t P

Before nursing 48.22±2.85 48.09±3.14 0.243 0.808 After nursing care 35.05±2.17*,# 44.89±2.13* 25.690 <0.001

t 8.680 6.850

P <0.001 <0.001

Note: *indicates that SAS scores of this group were significantly lower

than those before nursing and that differences are statistically significant (P<0.001). #indicates that the value of SAS in this group was significantly lower

than that in the control group (P<0.001).

Figure 2. Comparison of SDS score between obser-vation group and control group before and after nurs-ing. *indicates that SDS scores of the two groups

after nursing were significantly lower than those

before nursing and that differences are statistically

significant (P<0.001). #indicates that SDS scores of the observation group after nursing were significant -ly lower than those of the control group after

nurs-ing and that differences are statistically significant

(P<0.001).

nificant differences in SAS scores

between the observation group and control group before nursing (P>0.05), while SAS scores of the observation group, after nursing,

were significantly lower than those

[image:4.612.91.290.237.438.2]4.02). Physical status, social and family status, emotional status, functional status, and

ovari-an covari-ancer specific module scores of the ob-servation group, after nursing, were significant -ly higher than those of the control group (P< 0.001, Table 5).

Discussion

In the current study, general data of the two groups of patients with ovarian cancer were

first compared. After confirming that the gen

-eral data of two groups had no significant dif -ferences and that the two groups of patients were comparable, SAS and SDS, nursing satis-faction, and quality of life scores of the two groups, before and after nursing, were com-pared. SAS and SDS scores of the observation

group, after treatment, were significantly lower

than those of the control group. Therefore, results suggest that clinical pathways com-bined with psychological intervention for pa- tients with ovarian cancer can better regulate patient moods than routine nursing. Anxiety and depression, as affective disorders, are common in complications after treatment of

er than those of patients with routine nurs- ing. Moreover, the psychological and emotional control of patients with psychological interven-tion was shown to be better [22, 23]. The above conclusions are in accord with present results. Nursing satisfaction scores between the ob- servation group and control group were also compared. It was found that nursing satisfac-tion, general satisfacsatisfac-tion, and total satisfact- ion scores of the observation group were

sig-nificantly higher than those of the control gro-up. Nursing dissatisfaction was significantly

lower than that of the control group. Therefore, results suggest that patient acceptance of clinical pathways combined with psychological

intervention was better [24, 25]. Finally, com -paring quality of life scores between the obser-vation group and control group, after nursing, it was found that physical status, social and fam-ily status, emotional status, functional status,

and ovarian cancer specific module scores of the observation group were significantly higher

than those of the control group. Previous stud-ies have shown that proper psychological inter-vention has a positive impact on physical,

psy-various diseases [16, 17]. Many clinical stud-ies have shown that anxi-ety and depression have a great impact on the recovery rates of pati- ents. Thus, proper nurs-ing can improve anxiety and depression, as well as other bad moods [18, 19]. These factors verify the importance of pres-ent results. Many studi- es concerning the psy-chological and emotion- al effects of different nursing models on pa- tients have shown that psychological and emo-tional changes of pati- ents are very important for follow-up treatment effects [20, 21]. Results have shown that SAS scores and SDS scores of patients with psycho-logical intervention

nurs-ing are significantly

low-Table 3. Comparison of SDS scores before and after nursing between the two groups

Group Observation group (n=63) Control group (n=63) t P

Before nursing 47.69±3.54 47.18±3.23 0.8447 0.400 After nursing care 34.01±1.66*,# 41.14±2.19* 20.590 <0.001

t 9.226 7.130

P <0.001 <0.001

Note: *indicates that SDS scores of this group are significantly lower than those before

nursing and that differences are statistically significant (P<0.001). #indicates that the

[image:5.612.90.397.98.174.2]SDS score of the group after nursing was significantly lower than that of the control group after nursing and that differences are statistically significant (P<0.001).

Table 4. Comparison of nursing satisfaction between the two groups [n (%)]

Group n Satisfied General Dissatisfied Total satisfaction of nursing

Observation group 63 50 (79.36)* 7 (11.11)* 6 (10.53)# 57 (90.48)*

Control group 63 14 (22.22) 26 (41.27) 23 (36.51) 40 (63.49)

X2 - - - 12.940

P - - - <0.001

Note: *indicates that nursing satisfaction in this group was significantly higher than that

in the control group and that differences are statistically significant (P<0.001). #indicates

[image:5.612.90.398.264.341.2]chological, and social statuses of patients [26- 28]. Results concerning the application of clini-cal pathways combined with psychologiclini-cal in- tervention in patients with ovarian cancer have played a certain reference role in daily nursing work.

However, adopting a rigid approach to mode- ling and implementation, clinical pathways has often been a challenge. The use of appropriate technology that may improve the acceptability of clinical pathways has not been explored. Therefore, the overall effectiveness and

bene-fits of such pathways in actual clinical practice should be verified in larger samples.

In conclusion, application of clinical pathways combined with psychological intervention in patients with ovarian cancer can effectively improve patient mental states, nursing satis-faction scores, and quality of life scores, com-pared to routine nursing methods.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Address correspondence to: Yongyan Ding, Jing- zhou Central Hospital, No.60 Jingzhou Middle Road, Jingzhou District, Jingzhou 434020, Hubei, China. Tel: +86-19902072850; E-mail: yongyanding@163. com

References

[1] Brebach R, Sharpe L, Costa DS, Rhodes P and Butow P. Psychological intervention targeting

distress for cancer patients: a meta-analytic study investigating uptake and adherence. Psychooncology 2016; 25: 882-890.

[2] Chauvet-Gelinier JC and Bonin B. Stress, anxi -ety and depression in heart disease patients: a major challenge for cardiac rehabilitation. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2017; 60: 6-12.

[3] Cicero G, De Luca R, Dorangricchia P, Lo Coco

G, Guarnaccia C, Fanale D, Calo V and Russo

A. Risk perception and psychological distress in genetic counselling for hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer. J Genet Couns 2017; 26: 999-1007.

[4] Cimarolli VR, Casten RJ, Rovner BW, Heyl V, So -rensen S and Horowitz A. Anxiety and depres-sion in patients with advanced macular degen-eration: current perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol 2016; 10: 55-63.

[5] Coburn SB, Bray F, Sherman ME and Trabert B.

International patterns and trends in ovarian cancer incidence, overall and by histologic subtype. Int J Cancer 2017; 140: 2451-2460. [6] Correa DD, Root JC, Kryza-Lacombe M, Mehta

M, Karimi S, Hensley ML and Relkin N. Brain

structure and function in patients with ovarian

cancer treated with first-line chemotherapy: a pilot study. Brain Imaging Behav 2017; 11:

1652-1663.

[7] Etkind SN, Daveson BA, Kwok W, Witt J, Bause

-wein C, Higginson IJ and Murtagh FE. Capture,

transfer, and feedback of patient-centered out-comes data in palliative care populations: does it make a difference? A systematic re-view. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015; 49: 611-624.

[8] Hagen J, Knizek BL and Hjelmeland H. Mental

health nurses’ experiences of caring for sui-cidal patients in psychiatric wards: an emotion-al endeavor. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2017; 31: 31-37.

[9] Huang H, Xu C, Wang Y, Meng C, Liu W, Zhao Y,

Huang XR, You W, Feng B, Zheng ZH, Huang Y,

Lan HY, Qin J and Xia Y. Lethal (3) malignant

brain tumor-like 2 (L3MBTL2) protein protects

against kidney injury by inhibiting the DNA damage-p53-apoptosis pathway in renal tubu-lar cells. Kidney Int 2018; 93: 855-870. [10] Hulbert-Williams NJ, Storey L and Wilson KG.

Psychological interventions for patients with

cancer: psychological flexibility and the poten -tial utility of acceptance and commitment ther-apy. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2015; 24: 15-27. [11] Jacobs IJ, Menon U, Ryan A, Gentry-Maharaj A,

Burnell M, Kalsi JK, Amso NN, Apostolidou S, Benjamin E, Cruickshank D, Crump DN, Davies SK, Dawnay A, Dobbs S, Fletcher G, Ford J,

[image:6.612.90.522.86.176.2]Godfrey K, Gunu R, Habib M, Hallett R, Herod J, Table 5. Comparison of quality of life scores between two groups of patients after nursing

Group Observation group (n=63) Control group (n=63) t P

Physical status 19.47±5.02 13.16±3.05 8.527 <0.001

Society and family status 25.37±2.84 16.34±2.90 17.660 <0.001 Emotional status situation 19.26±3.10 13.54±1.69 12.860 <0.001

Functional status 11.59±1.94 8.26±1.88 9.784 <0.001

Jenkins H, Karpinskyj C, Leeson S, Lewis SJ, Liston WR, Lopes A, Mould T, Murdoch J, Oram D, Rabideau DJ, Reynolds K, Scott I, Seif MW,

Sharma A, Singh N, Taylor J, Warburton F, Wid

-schwendter M, Williamson K, Woolas R, Fallow

-field L, McGuire AJ, Campbell S, Parmar M and

Skates SJ. Ovarian cancer screening and mor-tality in the uk collaborative trial of ovarian cancer screening (UKCTOCS): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387: 945-956. [12] Jeffe DB, Perez M, Liu Y, Collins KK, Aft RL and

Schootman M. Quality of life over time in wom-en diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ, early-stage invasive breast cancer, and

age-matched controls. Breast Cancer Res Treat

2012; 134: 379-391.

[13] Li W, Gao J, Wei S and Wang D. Application values of clinical nursing pathway in patients with acute cerebral hemorrhage. Exp Ther Med 2016; 11: 490-494.

[14] Lin XH, Lin CC, Wang YJ, Luo JC, Young SH,

Chen PH, Hou MC and Lee FY. Risk factors of

the peptic ulcer bleeding in aging uremia pa-tients under regular hemodialysis. J Chin Med Assoc 2018; 81: 1027-1032.

[15] Maass SW, Roorda C, Berendsen AJ, Verhaak PF and de Bock GH. The prevalence of

long-term symptoms of depression and anxiety af-ter breast cancer treatment: a systematic re-view. Maturitas 2015; 82: 100-108.

[16] Makar AP, Trope CG, Tummers P, Denys H and Vandecasteele K. Advanced ovarian cancer:

primary or interval debulking? Five categories

of patients in view of the results of randomized trials and tumor biology: primary debulking surgery and interval debulking surgery for ad-vanced ovarian cancer. Oncologist 2016; 21: 745-754.

[17] Mielcarek P, Nowicka-Sauer K and Kozaka J. Anxiety and depression in patients with ad-vanced ovarian cancer: a prospective study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2016; 37: 57-67. [18] Mishelmovich N, Arber A and Odelius A. Break

-ing significant news: the experience of clinical

nurse specialists in cancer and palliative care. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2016; 21: 153-159.

[19] Momsen AH, Hald K, Nielsen CV and Larsen ML. Effectiveness of expanded cardiac reha-bilitation in patients diagnosed with coronary heart disease: a systematic review protocol.

JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep

2017; 15: 212-219.

[20] Patch AM, Christie EL, Etemadmoghadam D,

Garsed DW, George J, Fereday S, Nones K, Cowin P, Alsop K, Bailey PJ, Kassahn KS, New

-ell F, Quinn MC, Kazakoff S, Quek K, Wilhelm-Benartzi C, Curry E, Leong HS; Australian Ovar

-ian Cancer Study Group, Hamilton A, Mileshkin L, Au-Yeung G, Kennedy C, Hung J, Chiew YE,

Harnett P, Friedlander M, Quinn M, Pyman J, Cordner S, O’Brien P, Leditschke J, Young G, Strachan K, Waring P, Azar W, Mitchell C, Trafi -cante N, Hendley J, Thorne H, Shackleton M, Miller DK, Arnau GM, Tothill RW, Holloway TP, Semple T, Harliwong I, Nourse C, Nourbakhsh

E, Manning S, Idrisoglu S, Bruxner TJ, Christ AN, Poudel B, Holmes O, Anderson M, Leonard C, Lonie A, Hall N, Wood S, Taylor DF, Xu Q, Fink

JL, Waddell N, Drapkin R, Stronach E, Gabra H,

Brown R, Jewell A, Nagaraj SH, Markham E,

Wilson PJ, Ellul J, McNally O, Doyle MA, Veduru-ru R, Stewart C, Lengyel E, Pearson JV, Waddell

N, deFazio A, Grimmond SM and Bowtell DD.

Whole-genome characterization of chemore-sistant ovarian cancer. Nature 2015; 521: 489-494.

[21] Querleu D, Planchamp F, Chiva L, Fotopoulou C, Barton D, Cibula D, Aletti G, Carinelli S, Creutzberg C, Davidson B, Harter P, Lundvall L, Marth C, Morice P, Rafii A, Ray-Coquard I, Rock -all A, Sessa C, van der Zee A, Vergote I and du

Bois A. European society of gynaecologic on -cology quality indicators for advanced ovarian cancer surgery. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2016; 26: 1354-1363.

[22] Ross L and Austin J. Spiritual needs and spiri-tual support preferences of people with end-stage heart failure and their carers: implica-tions for nurse managers. J Nurs Manag 2015; 23: 87-95.

[23] Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, Agin-Liebes G, Malone T, Cohen B, Mennenga SE, Belser A, Kalliontzi K, Babb J, Su Z, Corby P and Schmidt BL. Rapid

and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depres-sion in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharma-col 2016; 30: 1165-1180.

[24] Spiliotis J, Halkia E, Lianos E, Kalantzi N, Gri-vas A, Efstathiou E and Giassas S. Cytoreduc-tive surgery and HIPEC in recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: a prospective randomized phase III study. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22: 1570-1575.

[25] Tang ST, Chang WC, Chen JS, Chou WC, Hsieh CH and Chen CH. Associations of prognostic awareness/acceptance with psychological dis-tress, existential suffering, and quality of life in terminally ill cancer patients’ last year of life. Psychooncology 2016; 25: 455-462.

[26] Taylor F, Reasner DS, Carson RT, Deal LS, Foley C, Iovin R, Lundy JJ, Pompilus F, Shields AL and

func-tional dyspepsia: a preliminary conceptual model and an evaluation of the adequacy of existing instruments. Patient 2016; 9: 409-418.

[27] Watts S, Prescott P, Mason J, McLeod N and Lewith G. Depression and anxiety in ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analy-

sis of prevalence rates. BMJ Open 2015; 5:

e007618.

[28] Zhang P, Li CZ, Zhao YN, Xing FM, Chen CX, Tian XF and Tang QQ. The mediating role of