American

Journal

of Comprttationd L i n ~ t t i c r

Microfjchc $ 7A GOAL-ORIENTED

MODEL

OF

N

DALOGE

J m s

A.

Moore

James;

A*

hsvinWittiam C.

Maw

USCflnf

ormation Scicncc~lnclitde

4676

Admiralty Way

Marina

del

Rey,Cdifornia

9029

1

Thc

research reported hereto was gupporlrd by thePorronnel md

Tra,in,trtg P ~ t r : l r r 11A Modcl of Dialogue

SUMMARY

Within a view of ianguagc users as problem solvers, speakers arc seen as creating uttcrsnccs i n pursuit of thcir own goals. Dialogue

"works"

because

this

activitytends

to scrvc goals of both participants. ,k Hcncc, f o r the model of dialogue c o r n p r c h c n s i o n prcscnted here, rccognifion of these goals of the speaker i s central to the c o m p r e h e n s i o n4 " of d i a l o ~ u c ,

Wc have found that dialogues arc conrposud of structured interactions rcpresanted by

collections

of knowledge which dcscri be the i n t c r r e l a t c d goals ofthe

participants.We

call

thcsc k n a w l c d ~ c structures "Dialogue-games" (DGg). This paper describes DGs in g c n c r a l , a particular one (the Hclping-DG) in some detail, how OGs are u s e d by our D i a l o g ~ c - g a m e Model(DGM),

and the benefits of this model.A

DG

consists of three parts: the Parameters (the two roles fillcd by t h c participants, and the topic),the

Pnramcter Spccifications ( a set of predicates on t h ePararndcrs), and

t h e

Components (a sequcncc of goalshgld

bythe

participants i nthe

course of

the dialogue).

For cxample, i n the Helping-DG, the Parameters a r e HELPER, HELPEE ( t h e rolcs)

and

TASK(the

topic).T h e

Spccifications are: 1) TheHELPEE

wants to p e r t o r mt h e

TASK: 2) thc HELPEE wants t o bca6/e

t o do i t but 3) the HELPEE i s not able to. 4) TheILELPER wants t o enable

the

HELPEE t o d othe

TASKand

5)

t h e

HELPER i s ab/e t oprovide t h i s help. The Componcntr specify that 1) t h e HELPEE wants t o e s t a b l i s h a context by describing a collection of unexceptional events (a parlial performance of the TASK): 2) he also

wants

to dcscribc some sort of unresirable surprise: then 3) the. I-IELPER wants t ocxplain

the violation of expectation so that the HELPEE can avoid ita'nd

get on witht h e

TASK.

T h e DGM makes use of DGs in fiue stages of processing: Nomination, Recognition,

Instantiation, Conduct and Termination.

Thc DGM models e a c h participant's knowlcd,ge, goal and attention states. A mcchanisrn adds t o the

attention

state,cmcepts

"suggested" by those already in attention. Whcn a hearer sees himself orhis partner

a spotentially

filling arole

in

a DG(by fulfillingone o r m o r e demands of the DG's Specifications) then that DG i s brought into attention (Nominated),

DGs can bc nominated by weak evidence: Recognition i s the step of verifying that

these DGs arc

plausibly

consistent with the currcnt state ofthe

model. Thosa which arcA

Model

of

Dialogue

DGs

which

surviveLhc

Recognition

stagparc

Instantiated

by

asserting (as

assumptions)

all

the

Specifications

not

ye1

rcprcscnicd as

holding.

For

example, when

a

person says "Do

you

have a

match?",

instantiation,

by

the

hcarer (of

t h e - ~ c t i o n - s c k

DG)

dcrivcs

asscrtionr;

that thc

speaker

does nothave

a

match

and wants

the

hcarer

t o

givehim

one,The

Conduct

of

ihc

DG

i srnodclcd

by

tracking

the

pursuitand

fulfillment

ofthe

participants'

goals

as

rcprescntcd

in

the

Components.

Whcn

tho

DGM

dctcplsthat

onc

parlicipant

no

longer

regards

a Specification

asholding,

this

crcatcs

an cxpcctation

of

the

Termination of

this

phase

ofthe

dialogue--there

i s

no

longer

apossibility

that

it

will

serveboth participants'

goals,

A

Modcl of DialogueCONTENTS

2.

St~tcrrrcnt of thc Problam3.

Post

Rcscarch

on LanguageComprchcnsion

4.

Thc S h o p c ofI h c

Thcory5. Thc Dialogue-came Modcl

5 , l

What's

ina

Game?5.1.1 Paramctcrs

5.1.2 Paramctcr Specifications 5.1.3 Components

5.1.4 Bidding and Accepting

5.2

T h e

Helping-gamc,an

Examplc5.3

Dialogue-gamcs i n the C o m p r c h c n s i ~ n cf C i a l c d ~ e5.3.1 P r o c c s s i n e Environment 5.3.2 Nomination

5.3.3

Rccognition

A

Modol ofDialogue

5.3.5 Condtrct

5.3.6 Tcrmination

5.4

T h e Dialogue-game Proccsscs5.4.1

Long-term Memory(LTM)

5.4.2 Workspace (WS)

5.4.3

Parser

5.4.4 Protcus

5.4.5 Match

5.4.6 Deduce

5.4.7

Dialogue-game

Manager 5.4.8 Pronoun Processes6. Deficiencies i n Current Man-machine Communication

A

Modcl

of DialogueSTATEMENT

OF

THE

PROBLEM

Thc

broadest goal of our researchhas

been

to improve the sorry state of interactive man-machine communication, including its appearance of complexity, rigidity,lack

of continuity and t h e difficulty it poses for many people to acquire useful levels of cornpctcnce. I n our pursuit of this goal, w e have adopted-the following t w o assumptions:Assumption

L:

When pcople communicate w i t h machines, they do so b yusing

their already well-dcvelopcd ability to communicate w i t h other people.Assumption 2: The effectiveness of this communication i s diminished b y any adaptation required of the human.

A scientific understanding of how people cvmmunicate i s thus relevant to the design of man-machine communication schemes, but suchknowledge i s seldom used i n the design process. Since human communication skills have not been characterized at a level of

clctsil appropriate for guiding design, interface designers have not been able to take into account some major determinants of

their

succcss.The opcrativc goal of our research was therefore to creatd a mode/ of human

communicafion at an appropriate level of detail to benefit man-machine communication

design. Any form of communication must be based on ,knowledge shared b y t h e individuals engazed i n that communication. However, the nature of this shared knowladgs and how i s

i t

uscd inthe

communicative process have not been w e l l undcrstood. We have developed a working hypothesis whichhas

deeply affected t h e r-csearch:Hypothesis: People know that certain kinds of goals may be pursued by communication, and they know which

kinds

of communication acts correspond t o w h i c h goals.Tho

use of this knowledge is essential t o comprehending dialogue.I n particular, a pcrson generates an utterance to advance one or more of his o w n goals.

Thus,

to assimilate a particular utterance,it

i s necessary to identify w h y the person saidi't.

A

Model of Dialogue.1.

A

study

of naturally occurring language to discover regularities of usage and t o determinewhat these

regularities mean l othe

users of the language.2.

The representation of there regularities as knowledge structuresand

processes i n a dialogue model.3.

T h e

establishment of standards bywhich

themodel's

performance can be comparedwith that

of humans on closely relatedtasks.

We have adopted two additional, tactical constraints on

t h e

task:1.

We have modeled onlythe

receptive aspects of communication.2.

W c - h a v e examined only d i a l q u c communication, interaction i n real-time,by exactly t w o people. These dialogues were conducted over

a

r c s t t i c t c dmedium so i h a t there was no visual or intonational communication not captured

A

~ o d c l

of DialoguePAST

RESEARCH

ON

LANGUAGE COMPREHENSION

Most of the research jnto language comprehension

has

focused onthe

comprchcnsion of single sentences or fragments of sentences. However some research

has

indicatedthe

importance ofthe

context

createdby

surrounding sentences onthe

comprchcnsion of an individual sentence. One specific model for the form of t h i s multi-scntcntial knowledge i s the "story schema", organized within a story grammar (Rurnclhart,

1975).

This modelhas

been supportbd'by

the results 6f story recalls (Rumcl hart,1975:

Thorndyke,1977).

Other similar kinds of theoretical constructs for organizing multiple srntcnces of stories have been proposed called: "frames" (Minsky,1975:

Charniak, 1975), "scripts" (SchankQ

Abelson,1975),

and "commonsense algorithms" (Ricgcr,1975).

To

account forthe

conductand

comprchcnsion of dialogues, mu1 ti-scntcntialknowlcdgc units have also bccn proposed by linguists and sociolinguists t o explain

certain kinds of rcgul ari tics observed in naturally occurring dialogues. These rcgularitics have bccn called "rules" by Labov

&

Fanshel (19.74) and"sequences"

by Sacks, Schagloff,&

Jefferson (1974).Once these multi-scntential knowledge units

a r e

evoked, they serve as a basis f o r comprehending the~successive inputs. This is achieved by generating expectations andby

providinga

framework

for integrating the comprehcnsion of an utterance w i t h that of i t s prcdcccssors. Recently, we have propased (Leuin&

Moore, 1976:1977,

Mann, M o o r cRr

Lcvin,1977)

multi-scntential knowledge units that are specified primarily by t h e speaker's and hcarcr's goals. Thcsc goal-oriented units, w h i c h w e callDialogue-gsmcs[l],

specify the kinds of language interactions i n w h i c h people engage, r a t h c r than the spccific content of thcsc intcractions. Pcoplc use l a n g u a ~ c primarily t o comrnunicatcwith

other pcoplc l o achieve their own goals. Thc Dialoguc-gamemu1 ti-scntontial structures wcrc dcvcloped to represent this knowledge about

language

and how i t can be uscd to achicve goals.-[I]

Thc

term "Oialoguc-game" was adopted by analogy from Wittgcnstcin's term ' Y a n ~ u a g c game" ( ~ i t t ~ c n s t c i n , 1 9 8). a Howcvcr, Dialogue-games reprcs6ht knowlcdgo?=

pcoplc h i v e dbout language as

uscd

to purGuo goals, rathcr than Wittgcnrtcin's m o p ~ c n c r a l . notion. Althouehother

"game-."

arc similar, thc propcrtios of .Dia)ofiuo-,gornesA

M o d e l of DialogueAn important problem for rcscarchcrs of language comprehension i s posed by

scntences w i t h w h i c h tho speaker performs what philosophers of language h a v e c a l l e d "indirect spccch acts" (Searle,

1969).

The direct comprehension of these sentences f a i l s t o d e r i v e the main communicative~effcct. For example, declarative scntenccs can beused

toseek

information ("1 nced to know your Social Security number."): questions can beu-scd to convey information

("Did

you know that John and Harriet got married?") or t orequest an action ("Could you pass the salt?''). These kinds of utterances, w h i c h have b c c n extensively analyzed b y philosophers of language (Austin, 1962: Searle, 196 9,

1975:

Grice, 1975), are not handled satisfactorily b y any of the current theories of t h e d i r c c t comprchcnsion of language. However, these indirect language usagesara

w i d e s p r e a d i n naturally occurring language--even two-year-old c h i l d r e n can comprehend indirectrequests

for action almost as well as dircct requests (Shatz,1975).

O n e

t h e o r y proposcd to account for these indirect uses of language i s based on theconcept of "convcrsotional postulates" (Grice, 1975: Gordon

Q

Lakoff,1 9 7 1).

I f t h e d i r c c t comprchcnsion of an utterance i s implausible, then the indirect meaning i s d e r i v e dusing these postulates. Clark

&

Lucy (1 975) formalized and tested t h i s model, and found t h a t people's rasponse times tend to support a three-stage model (deriving the l i t e r a l mcaning,check

i t s plausibility and, i f implausible, dcriving the "intended" meaning" from convcrsational rules).I n

general, this

approach to i n d i r e d speech acts i s infc~ence-bascd, depending on t h e application of conversational rules to inferthe

indirect meaning fromt h e

d i r c c t mcaning and t h e context. A different approachh a s

been

proposcd b y L s b o v ~ f i F a n s ~ c l(1 974)

and by Levin&

Moore (1976:1977).

Multi-sentential knowledge, organizing a scgmcnt of language interaction, can form the basis for deriving t h e indikect effect of u t t c r ~ n c c w i t h i n the segment. For example, a multi-sentential structure f o r an information-seeking interaction can sypply the appropriate context for interpreting thesubscqucnt utterances to s ~ c k and t-hen supply information. The i n f c r c n c c - b a s c d a p p r o a c h r c q u i r c s one set of c o n v c r s ~ t i o n a l rulc-, for information requests, a dif f c r c n t 9ct

of r u l c s f o r answers t o these rcquc:ts, and a way t o tic thcnc t w o rulc sets together. The Dialogue-game model postulates a single k n o w l c d ~ e struclurc for this kind of interaction, w i t h coopcrating proccssc; for: (1) rccognizinp; when this kind of interaction i s proposcd,

A M o d c l of Dialogue

THE

SHAPE OF THE THEORY

Our t h c o r y of human language use

has

bccn strongly influenced by w o r k in human p r o b l e m solving (NcwcllXI

Simon,1972)

in w h i c h the bchavior of a human i s modeled as an information. processing system, having goals to pursue and selecting actions w h i c h t e n d t o schicvc thcsc goals. Wc view humans as engaging i n linguistic b c h a v i o r in o r d e r t o advance t h e state of certain of thcir eoals. Thcy dccide to use language, they sclcct( o r accept) t h c other participant for a dialogue, they choose t h e details of linguistic c x p r c s s i o n

--

all

with

the expectationthat

some of their desired state specifications canthcrcby be rcalizcd,

In this t h c o r y of lancuagc, a participant i n a linguistic exchange views t h e other as

an indcpcndcnt information-processing system, w i t h separate knowledge, goals, a b i l i t i e s and acccss l o the world. A spcsker h a s a range of potcntial changes he can c f f c c t i n h i s l i ~ t c n c r , a corresponding collection of linguistic actions w h i c h may result in e a c h such chance, and some notion of the conscqucnccs of performing each of these. T h e spcokcr may view t h e h c a r c r as a resource for information, a potential actor, or as an o b j e c t t o bc

moldcd i n t o sorrrc dcsircd state.

A dialogue involves t w o speakers, w h o altcrnatc as hearers. I n choosing t o i n i t i a t e o r conlinuc tho c x c h a n y , ~ , a participant attcmpts to satisfy his own goals: in i n t c r p r c t i n g on u t t c r a n c c of h i s partner, each participant attcmpts to find the w a y in w h i c h that

utterance serves the

goals

of his partner. Thus a dialoguo continues because theparticipants continue t o scc i t as furthering t h c i r own goals. Likewise, w h e n t h e dialoguc no l o n ~ o r serves the goals of one of

the

participants, i t i s redirected t o new goals o rtcrminatcd.

t h i s rrlcchanism of joint

interaction,

v i a cxchange of uttcranccs, i n pursuit of d c s i r c d t.itcs, i s uscful for ochiovihg ccrtain relatcd pairs +of participanls' ~ o a l s ( c . ~ . ,I t v ~ r n i rlr./tcact~inc, buyinc/sc\ling, gctting h c i p / ~ i v i n g hclp, ...). Many of thcsc paired sets of I correspond t o hichly structured collections of knowlcdgc, shorcd by

thc

rncrnbcrr, o f thc langunpc community. Thcsc ~ollcctions specify such things as: 1) what chnractcri:tics an individual must h a v c to cngagc in a dialogue of this sort, 2) how t h i s dialocuc i s initiated, pursued and tcrminatcd, 3) what ranee .of infarmation can bo comrnunicotcd imp1 i c i t l y , and 4) undcr what Circumstances tho dialoguo will "succeed"( s c r v c tho function for

which

it

was initiated) and howthis &ill

bo cxhibitcd in the participants7 bck~uvior.VJo h ~ allr:mptc:d ~ o to rrproscnt those collr:.ctiong_of knowlcdgc and tho wily i n

w t ~ i c h t h c y arc u:cd t o f a c i l i t ~ t o tho cornprchcnsion of a d i a l a ~ u a , in tha O i n l o e ~ ~ o t;nrno

A

Model

of DialogueTHE

DIALOGUE-GAME

MODEL

T h i s section describes our Dialogue-game Model at i t s current state of dcvclopmcnt.

I t

starts w i t h a brdef overview of dialogue andhow it

i s structured, t h e n d e s c r i b e sthe

dominant knowledge structuresw h i c h

guidethe model,

and f i n a l l ydcscribcs

a

set of processeswhich

applythese

knowledge structures t o text t o c o m p r e h e n d i tWithin

the

mb.dcl.,

each

participantin

adialogue i s simply

pursuinghis own goals

of t h c moment. The t w o participants interactsmoothly

becausethe

conventions of communication coordinate t h e i r goals and givethem

continuihg reasonst o

speak andlisten. These goals have

a

number of attributeswhich are

not necessarily consequences of c i t h c rhuman

activity

in general,

or communicationin

particula'r;but

which

arenonetheless

characteristic

ofhuman

communication i n the form of dialogue:1.

Goals

are cooperatively

esta5lished.

Bidding

and

acceptance

activities s e r v e t o intfoduce goals.2. Goa/s.aremufua//yknown. E a c h p a r t y a s s u m e s o r c o m e s t p k n o w goals of the othcr, and each interprets the entire dialogue relative to c u r r e n t l y known

goals.

3. G o a l s a r e c o n f i e u ~ e d b y c o n v e n f i o n . Setsofgoalsforusein dialogue

(and

othcrlwguage

use as well) aretacitly'known and

employedby

all

competent spe;l&rs o f t h e language.4.

Goa/s arebilateral.

Each dialogue participant assumes goals complementary tothose

of his partner.5.

Gas/ssreubiguilous.A h o a r e r v i e w s t h c s p e ~ k e r a s a l w a y s

having goalshc

i s pursuing by speaking.Furthermore,

the

hearer recognizes anduses

thcsc

goals as part of h i s understanding ofthe

utterance.An ~ninlerrupted dialogue goes through three phases:

establishing goals, pcir sui ng eobl s,

A Modcl

of Dialogue

Typically this sequcncc i s repeated several times over the coursc of a few rninutcs.

We havc crcotcd knowlcdse structurcs to rcprescnt these convcntions,, and proccsscs to apply the conventions to actual dialo~ucs to comprehend them; Since

t h e

knowledsc structures dominatc

all

of the activity, they are describedfirst.

The

assimilation of an uttcranco in the dialogue

i s

rcprcscntcd in this model by a sequence of modifica\ions of a "Work~pacc"[2]which

rcprcscnfs the attention or awareness af the listening party.Tho

modificN~tions arc roughly cyclic:1.

A ncw item of textf

i s

brought into attention throughthe

"Par scr."[-212.

Interpretive conscqucnces~ofT

are developed i n the Workspace bya

variety of proccsscs.3. An exprcssian E appears in thc Wor'kspace w h i c h specifics the relation between

i

and

the imputed goals of the spcaker ofT.

This final cxprcssion i s of coursc a formal expression i n the knowledge representation of the modcl.

E

rcprcsents the proposition (held by the hcarer) thatin

uttering

T,

the spcaker was performing an act in pursuit ofG,

a-spbaker's goal known to thc hcarer. Sucrcssful comprchcnsioni s

cquatcdwith

relating tcxt to salisf action of spcakcr's goals.T o makc an

explicit account of dialoguc in this way, wc now describcthe

knowledge structures that rcprcscnt those c~~nvcgtions which supply tho goals forthe

participants t o pursue. I n particular, w c will anewcr thc following thrco questions:1. What i s thc k n o w l c d ~ o wo arc rcprescnting

within

tho dofinition ofo

pclrlicular Dialogue-gamc7

2,

Howi s

this

knowledge?

used to modcltho

roccptive acts of dialogue participant8- - - e - - * - e - - - e - - ' - m - d e w -

[2]'Thc

F3ar.;cr and thc Workspzlco oro port% of tho p r o c a r g modeland

aro d e r , ~ r ~ t ~ i ! d ina

k Model of Dialogue

3. W h a t * s o r t of processes docs

i t

take to supportthis

model?A Dialogue-game consists of

thrcc?

parts: a set af Parameters, a collection of S p c o / ~ c , ~ l l ' o n s that apply to these Paramctcrs throughout t h e conduct of the game,a n d

a p a r t i a l l y o r d c r c d set of Components characterizing t h e dynamic aspects of t h e came. F o rthe

bslancc of this section, we will elaborate on thesethree

p a r t s and c x c m p l i f ythese

with

an cxalliple of the Helping-game.D i a l o ~ u e - g a m e s capture a certain collection of inforhation, common across many

d i a l v ~ u c s .

However, the individual participants involved and t h e content s u b j e c t df t h e dialoguc may y a r y freely over dialogues described b y the same Dialogue-game. T o r e p r e s e n t this, e a c h Dialogue-game has a set of Parameters w h i c h assume specific v a l u e s f o r each p a r t i c u l a r dialogue.Thc dialogue types w c have

represented

so far as Dialogue-games have each r e q u i r e d o n l ythrcc

Parameters:the

t w o participants involved (called "Roles"), a n d thes u b j c c t of

the

dialogue (called "Topic").P a r a r n d c r Spccifications

Onc of t h e major aspects distinguishing various types of d'ialogucs i s t h e set of goals

hcld

by t h e participants. Another such aspect i s t h eset

of kno'wledgc states oft h e

participants. We have found that each type of dialogue h a s a char$cteristic set of eaal

and

k n o w l e d g e states of the participants, vis-a-vis each otherand

the subject. W i t h i n the formalism of the Dialogue-game, these are called the Parameter Spccifications, and a r e r c p r p s c n t e d b y a collection of predicates on the Parameters.These Spccifications are known to

the

participants of t h e dialogue, and the r e q u i r e m e n t that they be satisfied duringthe

conduct of a game i s used by t h p p a r t i c i p a n t s t o signal what Dialogue-gamesthey

wish to conduct, t o recognizewhat

game i s b e i n g bid,t o dccide how t o respond t o a bid, to conduct the game once t h e

bid

i s accepted, and t o terminate t h e garno w h e n appropriate. These Spccifications also provide t h e means withany natural d i a l o g ~ c . Examples

and

discussions of these Specifications will accompanythe f o l l o w i n g d e s c r i p t i o n of !he Helping-game.

Componcnts

W h i l e the Paramctsr Spccificstions represent those aspects of a dialogue t y p e t h a t r c m a i n constant throughout the course of a dialogue of that type, we h a v e also found t h a t c e r t a i n aspects change i n systematic ways. Thcse are reprcsented i n Dialogue-games a5 Components. I n t h e Dialogue-games we have developed so far, t h e Components a r e

r c p r c s c n t c d 9s a set of participants' subgoals, partially ordered i n time.

Bidding and Accepting

Eiddinp, and Acccptancc arc entry operations which p e o p l e use t o c n t c r D i a l o ~ u c - g a m e s . Bidding

1. identifies thc game,

2. indicates the bidder s interest i n pursuing t'hc game,

3.

idcn tifies the Psramctcr configuration intcnded.Bidding i s performed many diffcrcnt ways, often v e r y b r i c f l y .

I t

i s t y p i c a l l y t h esource of a great deal of i m p l i c i t comrnunicotion, since a b r i c f bid can cornmunicatc all of

t h e

Pararncters and t h c i r Specifications f o r j h e Dialogue-game being bid.Acceptance i s one of t h o typical responses to a Bid, and leads to p u r w i t of t h c game.

Acccptsncc cxhibi t:.

1. acknov~lcdy,rncnt that 3 bid t ~ s s h c c n

rnndc,

2. r s c o g n i t i s n of t h c particul;~r OiaIo~;uc-garrlr? ;~nd 13aramc:tcr~ liid,

3. ar,re.crn~nt t o pursuc t h e l;;~trio,

4. assumption of thc A ~ c c p t o r ' ; rolfc i n I t ) ( : U i ; ~ l o l ; ~ ~ t : 1:;jrtlc:.

Acccptoncc i s o1tc.n implicit, c p e c i . ~ I l y in I c1Iii!i'vtbly inforrn;ll dial oj;lrrl. c:an bc

i n d i ~ a t c d b y stat(:rncnk of clgr(:(:nir:r~t or ;~pprov;ll, or h y b r : l ; i n n ~ r l ~ t o ptrr;iJcl t h c 1;hrnc.

( i , sttcrnpts to satisfy it-ic goals). A to c l c c ( ~ p t a r ~ r c i n r l t ~ d o rcjr:cting,

n c ~ o t i a t i n r , and i ~ n o r i n c .

C i d d i n ~ and acccptnricc appear t o l j n p i ~ r t ' of 1;arnc r : c ~ l r y f o r ;dl of t h c

Dial oguc- games of o r d ~ n a r y a d ~ ~ l t dislu;.uc. T i ~ y are .il:n i nv'olvcd i n f;amc trtrrni

n:~Iian.

In

thc ca:r of t ~ r m i n d i o n , t h r c e altcrnat~vc.:;rrfa

po:<iblc: ~ r l l r l r r u p t i u n :~nd 5pont:lncousA

Model

of DialogueOnce a eamc

has

bccnbid

and acccptcd, the two participants each pursuet h e

subgoals

spccificd for their role by the Components ofthis

game.Thcse

subgoals

a r e

mutually

complcn~cntary,each

set facilitating the other. Furthermore, by the time t h e tcrrninati on stage has been rcachcd, pursuit oft h e

Component-specified

subgoalswill

h a v e assurcd satisfaction of the higher, initial goals of

the

participants, forwhich

t h e Came was initiatedin

thc first place.I n

this

scction, wc c.xhibita

specific Diolocuc-game: theHelping

-

gn/ne.This

game i s prcscntcd in an informal rcprcsentation, i n order t o emphasize the informational content,

rather than the representational power of

our formalism.Later

i n

this

report wewill

prcscntt h c

formal analocue ofthis

same game. I n what follows, the b o l d faceindicates t h e information

contained in tho representation ofthis particular

Dialogue-game:the tcxt in regular type i s explanatory commentary.

The (annotated) Helping-game.

- - - - - - - - 1 - - - 1 1 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

-P n m n ~ c l c r s :

HELPEE,

HELPER,

and

TASK.

The

HELPEE

wantshelp

fromthe HELPEE.

The

TASK

i ssome

sort

ofa

problem, otherwise unspecified.

Paran~eler

Specificat

ions:HELPEE:

wantsto

performTASK.

HELPFE:

wants

lo

be

able

lo

perform

TASK.

HELPEE:

not ab/el o

perform

TASK.

HELPEE:

p e r m i t t e d t i i p e r f i r mTASK.

A

Modcl

of DialogueThcse

Spccificationsnot

only constrain w h o would qualifyas filling the rolc of

HELPEE,

but also provide reliable information aboutt h e

HELPEE,

given that this individual i s believedt o

beengaged i n the Helping-game. This prohibits someone from

asking for help on

a

problemhe

did not want solved. Similarly,i f

one

r c c ~ i v c s whathe

judges t o be a sincere request for help to do some task,the

helper normally as:umes thatthe

requesterhas

thenecessary

authority to do the task,i f

only he knewhow.

HELPER:

wants t o

helpHELPEE

perform TASK.HELPER:

able

to

provide

help.

HELPER:

a person.

So,

i n

ordcr to be aHELPER,

an individual must be willing andable t o provide the needed assistance. Since this Dialogue-game rcprcscnts shared knowledge, the HELPER knows

t h e s e

Spccifications, and therefore

will

not b i d the Helping-game to someone who i s not likely to meet them.And

similarly, no onewho

fails to meet these Specifications (andknows he

fails) w i l l accepta bid

for the Helping-gamewith

himselfas HELPER.

Components

of

the

Helping

-

game:T h c r e are three components: the first t w o constitute the "Diagnosis" phase

to

communicate what the problem is..

HELPEE

wantsHEfPFR

to

know

abouta

sef of unexcepfiona/,acfuuii/

events.

'The HELPEE

sets upa

context by describinga

situation w h e r e everything, sofar,

i s going well. Sincethe HELPEE

assumesthat

the

TASK

i s understoodby

the

HELPER,

he

also assumesthat

theHELPER

shares his expectations for r~bsequentA

Modcl

of Dialogue2.

HELPEEwc.mts

HELPERfoknowabouf:

//

a set of exceptional events

whkh

occurredor

2)

a set of expected,unexcepflbnal events

which

did

not

occur.This

pattern ofa

Helping-game i s sufficiently well known to the participants, that theHELPEE

almost never needs t o actually aska

question atthis

point. By simply exhibitinga

failure of expectation, theHELPEE has

communicated that this acts asa

block

t ohis

successfully pursuingthe

TASK.

The

HELPER

i s expected to explain w h ythe failure occurred

andhow

HELPEE

can-avoid

it

or

otherwise continue inthe

TASK.

The

third

componcnt specifies the'Treatment"

phase w h e r ethe

HELPER

communicates an explanationfor

the

perceived failure.3

HELPER

wants

HELPEE

fo

know

about an actionwhich

w i l l

avoidt h e

undesired event

or cause the

desired

one.The context

description enablesthe

HELPEE

t oidentify a

collection

of activitieswhich

he understands,and in which

theHELPEE

i sattempting

to participate.The

violation-of-expectation description points out just where

the

HELPEE's

image ofthe

activities differs fromthe

correct image.I t

i s from this area of differencethat

the

HELPER

selectsan

actionA

Model of Dialogue#ia/o,mue

-

games i nthe

Con?pre/rension of DialogueI n this section we describe the five stages of dialogue assimilation and detail the

involvement of Dialogue-games w i t h ~ a c h stage:

1) nomination,

2) recognition,

3) instantiation,

4) conduct,

5)

termination.Proccssi ng Environment

Our description of the model should be viewed as representing t h e changing coy,nitive state of one of the participants, throunhout the course of

the

dialogue. That is,two models are involved,

one

for each participant. Since the same processing occurs for both, we w i l l describeonly

one.T h c

Dialogue-Game Modcl consists of a Long-Term Memory(LTM),

a Workspacc(WS), and a set of proccsscs that modify the contents of

WS,

contingent upon t h e contents ofLTM

a n d

WS.

LTM

conbinsa

rcprescntation ofthe

knowledgethat

the partigulardi ologuc participant

bl

ines to the dialogue b c f o ~ ei t

starts. This includcs knowlcdgc aboutt h e

world, relevant objects, processes, concepts, the cognitive statc of h i s partner in dialogue, rules of inference and evidence, as well as linguistic knowlcdp;e (words and t h c i r semantic rcprcscntation, case frames for verbsand

predicates and the multi-turn language s'trbctures, t h e Dialogue-games).WS i s the volatile short-term rncmory of thc modcl, containing all the partial and temporary rcsults of processing. The contcnte of

WS

at any momcnt rcprc.;cnt thc madel's state of comprchcnsion and focus at that point. Tho processes arc autonomousspecialists, opcrl~tiny: indcpcndcntly and in parallel, t o modify thqentitics in WS (callcd "activations"). Thcsc proccsscs

a r c

also influcnccd by the contents of WS, as w e l l a.; b yt h c

knowlcdgc inLTM.

Thus, WS i s theplace

in which thcso concurrcnt~ly operating proccsscs interact with eachothcr.

This

anarchistic control structure rcscrnblcs thatA Modcl

ofDialogue

Nomination

W h e n d i a l o ~ u c participants propose

a

new type of interaction, they do not consistently use any single w o r d o r phrase to introducc the interaction.Thus

we cannot dcterminc w h i c h Dialogue-games representthe

dialoguc type througha

simple invocation by namc orany

othcr pre-known collection of words or phrases. Instcadthe

d i o l o ~ u c type i s cornmunicatcd by attempts to establish various entities as t h e values of

the

Psi

actcrs

ofihe

dcsircd Dialogue-game. Thus, an utterance w h i c h i s cornprchcndcd as associating an entity (a-person or a concept)with

a

Parameter of aDi

aloguc-game suggeststhat

Dialogue-game asa

possibilily

for initiation.

The Dialogue-Game

Modcl

has two ways i n which these nominations of n c w D i a l o ~ u c - g a m e s occur. One of the processes of the modcl i s a "spreading activation" p r o c c s scall&

Protcus (Lcvin,1976).

Protcus gcncratcs n e w activations i nWS

onthc

basic of cclations in LTM, from concepts (nodes i nthe

semantic network) that are already i nWS.

Protcus brings into focus concepts somehow related t o those alreadythcrc.

A

collection

of concepts in WSleads

to focusing on some aspect of a particular Dialocuc-game, in this sense "nominating" i t as a possiblenew

Dialoeue-game.MATCH

and DEDUCE are two of thc modcl s processeswhich

operatci n

.conjunctionto ccncratc

ncw

activations from existing ones, means of findingand

ap,prp@rulc-liketransformations, Thcy operate through partial match

and

plausiblei

nfcrencetcchniques,and i f thcy activate Pardrnetcrs, thcn the Dialogue-gsrnc that contains those ~ a r a r n d t c r s

bccomcs nomina,tcd a s . a candidate Dialogue-game.

Match

and Deduce operate to,gether as a kind of production system (Newell,1973).

F o r cx;lmplc, from the input utterance:

"I

t r i e d t o send a message to <person> at <computer-site3 and it~didn't go."the

following t w o scqucnccs of associationsand

inferences result:( l a )

I

t r j c d toX.(25) 1 wpntcd to

X.

(3a) 1'want to X.

(4a) HELPEE wants to do TASK.

(

I

b)

It

didn't

go.(2b)

What I

t r i e d todo didn't

work.(3b)

X

didn't

work.(4b)

I

can'tX.

(58)

1

don't

know ha

toX.

A

Model

of Dialogue(Where:

I

=

HELPEE

and

X=

doTASK

=

send a message to <person>at

<computer-site>.)A t

t h i s

point,(45)

and(6b),

since they are both Parameter Specifications forthe

Helping-game, causethe model to

focus onthis Dialogue-game,

in

effectnominating

i tas

an

organizing structure forthe dialogue

being initiated.Thc

proccsscsdescribed

so far are reasonably unselectiveand

may

activate a number ofpossible

Dialogue-eamcs,

some

of

which

may

be mutually

incompatible or

othcrwisc inappropriate.

The

Dialogue-garnc Manager investigates each ofthe

nomi

natcd Dial.oguc-games, verifying infcrcnccsbased on

the Parameter

Specifications,and

eliminating< those Dialogue-gamcs for which one or more Specifications arecontraclictcd.

A

second rncchanism (part of Protcus) identifies those activationswhich

are incornpatiblc and

scts aboutaccumulating evidence

in

support

ofa

decision

to accept oneand

d c l c t c the rest fromthe WS.

Fdr cxarnplc, suppose

the

question"How

do

I

getRUNOFF

to work?"lcads to

the

nomination

of twogames:

Info-scck-game (pcrson asking question wants to know answer) and

Info-probe-game (pcrson asking q u c d i ~ n wants to

k n ~ w

if

otherknows

answcr)Thcso I w o Dialocuc-~nrncs h a v e a l o t in common hut differ i n ono crucial

aspect,:

I n the Info-scck-gamc,t h c

qucctioncr docs not know the answcr t othc

question, whilc i nthc

Info-probc-gamehc

doc:. Thcsc two prcdicatcs arc rcprcscntcdin

the Parameter Spc.cifications oft hc

t w oDi

al.ogue-games,and

upon thcir joint nomination are discovarcdto bc contradictory. Prolcus rcprcsent:

this

d i ~ c o v e r y w i t ha

structurewhich ha5

the

A Model of, Dialogue

21

T h r o u g h these proccsscs, t h e number of candidate Dialogue-games i s reduced until

those remaining are rompatible w i t h each other and with the knowledge c u r r e n t l y in WS

and in

LTM.

I n s t a n t i a t i o n

Oncc a proposed Dialogue-game has successfully survived t h e f i l t e r i n g proce.Bses describe-d

above,

i t

i s thcn instantiated by t h e Dialogue-game Manager. Those Parameter Specifications not prcviou:ly known (represented inthe WS)

are e s t a b l i s h e d as n e w l y i n f c r r e d knowledge about the Parameters. A large p a r t of t h e i m p l i c i t communication b e t w e e n dialogue participants i s modeled through instantiation.T o i l l u s t r a t e this, suppose that the following come t o be r e p r e s e n t e d i n WS (i.e., known) in t h e

course

of assimilating an utterance:SPEAKER does not k n o w how t o do a TASK. S P E A ~ E R w a n t s t o k n o w how t o d o that TASK.

SPEAKER w a n t s

t-o

do t h e TASK*Thcso a r e

adequate t o nominate the Helping-game. I n t h e process of instantiating t h i s Dialogue-game, the following predicates are added to WS:SPEAKER b e l i e v e s HEARER knows h o w to do TASK,

SPEAKER

b e l i e v e s HEARER i s able t o tell him h o w to d oTASK.

SPEAKER believes HEARER i s w i l l i n g to tell him how to do TASK.. SPEAKER wants HEARER t o

tell

hirn.how t o doTASK.

SPEAKER

expects HEARER t o t'cll'him how to do TASK.Thc model predicts that jhcsc predicates w i l l bo implicitly communicated by an u t t e r a n c e which r;uccecds in instantiating thc Helping-game. This corresponds t o

a

dialogue

inwhich

"&I

can't gctthis

thing towork"

i otaken

t o eommuhicate t h o t ' t h c speakerwnnts to "get

this

thing to work" (even,though, on the surface, i t i s only a simpledeclarative

of t h e speaker9$ abi'lity).Conduct

Oncc

a

Dialogue-game i s instantiated, tho Dialogue-gameManagcr

i c guided by thcA

M o d e lof

Dialoguethe

dialogue

participants. For the speaker, thesegoals guidewhat he

i s next to say: forthc

hcarcr, these provide expectations for the functions to be served by the speaker ssubscqucnt

utterances.Thcse "tactical" goals are central to

our

theory of language: an utterance i s notdccmcd

tabe

comprehended until some direct consequence ofi t

i s seen as s e r v i n g a goal i m p u t e d to t h espcakcr

Furtherfiore, althoughthe

goals ofthe

~ o m p o n c n i s arc active only w i t h i n the conduct ef a particular game,their

pursuit leadsto

the satisfaction of t h e goals described in the Parameter §pccifications, w h i c h wereheld

bythe

participantsp r i o r t o

the

evocation cf ihe Dialogue-game.I n the case of t h e Helping-game,

t h e

goals i n tho "diagnostic" phase arc that thctIELPEE

d c s c r i b c a scquoncc of related, uncxceptional cvcnte leading up t o a failure of h i scxpectotions. Thcse goals model

t h e

state cyft h 6

HELPERas

he

assimilates

this

initialpart of t h c dialogue, both in that h e knows how tho H E ~ P E E i s attempting l o dcscribc h i s problcrn, and

also that

thc

HELPER

knows

whcn this phase i s past, andthc

time h a s come (Ihc "trcatrncnt" phase) for h i m to provide the help which h a s been implicitly rcquesteel.The processes described above perform

t h c

identification and p u r s u i t of D i a l o ~ u e - g a m e s . How,then,

arcDGs

terminated? Thc Parameter Specifications r c p r e s c n t thosc a:pects of dialogues that arc constant over that particular t y p e ofdialogue. T h e Oinloguc-Game Modcl

pushas this

a

step further in specifying that the D i s l o ~ u c - , g a m e continues onlysr

l o n g

a r the Parameter Specifications continuc t ohold.

Whcnevcr any predicate i n the Specificelion ceases to hold, then tho model prcdicls thoi rnpcr~ding tcrrnin;jtion of this Dio1oguc;garnc.

For

r_.xnrnplct, if t h eIIIIPEF'

na longer wants to pcrfarm thn T A S K (r:~lhrlr b y nccornplid--~ir~f: i t o r b y nb:rndonirl~ that goal), hv 'indicl~trr.i fhia with nn irttcsriinct. wlrich hd; f o r tr:rrnin:il~on. The: l i t , l p ~ n g game ihr:n tnrrnln:\tc~; this corrc;pr~nrl; lo lhq :imultsrir.ou~ tcrrr~instion of thc h o l p ~ n g interact~on.If

theHELPER

bccomc; unwilling l ogive h c l p , or discovtrrs that

hc

1s unelble,thc:n

Ihr! Eirlptng-game also terminiltcs. Again,we haddo

one

s i m p l c rule ,lh?it c o r c r ;h

di.dcr:;!y ofcasos--a

rule for torminationthat

A

Model

of Dialogue

The Dialogue

-

,name ProcessesIn

this section we describe the major process elements ofthe

Dialogue-GameModel.

Allthe

major

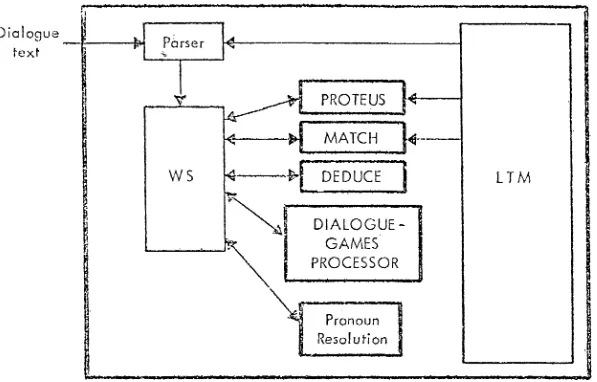

parts and their connectivity areshown in

Fieure1.

Thcseparts

( t w o rncmorics and six Proccsscs) w i l l each be described separately.Thc

appendix contains an extensive, detailed trace ofthe

model asi t

analyzes (viahand

simulation) a naturally occurring dialogue fragment. Finally, we w i l l summarize our experience with t h e model to date.Long-term Mcrnory

(LTM)

The Long-Term Memory i s the rnodcl's representation of a participant's knowledge

of the external world.

I t

contains the initial knowledge states of the participants:the

grammatical case frames, the semantic structures f o r word-senses, thoknowledge

of t h e s ~ b j c c t , m a t t e r of the d i a l o p u ~ , the various ways i n which dialoeues are structured, ctc.L T M i s a semantic network, containing a set of

nodes (also called concepts) and t h e relations that hold betweenthem

at

the

Iowost ievel.This information

i s stored i n t h e form of triples:<node-

1

relation node-2>Wc

havethis

machinery encoded and working--a6

1

1

complement ofread

and write primitives forthis

representation. However,i t has

proven awkward forus

to specify knowlcdgeat this

level, so we have implemented further machinery(named

SIM)

t otran.olatc

n-ary

predicates into

these triples.Thuq

far

a

predicate,

P,

having arguments

A 1, A2,

and A3,SIM

can be giventhe

input:PI:

(Alpha

P

Beta Gamma)[ m c a ~ i n g

that

P1

i s

defined to be aninstance

ofP (the predicate always

goesiR

s w dposition) w i t h arguments

Alpha

for A l , Beta for A2 and Gamma-?or A3.1 The resulting t r i p l e sw e

created:<P1 PRED

P>

<P1

A 1

ALPHA,

<Pl

A 2

BETA>

<PI

A 3GAMMA>

A

Model

of DialogueD i a l o g u e

[image:24.775.72.669.234.616.2]t e x t

A

Modcl

of Dialogue

.Mary

hit

Johnwith arock.

The

predicate

"HIT" ha's

two

mandatory

arguments (subject, object)

and

an optional

one

(instrument).

he

SIM

representation of t h i ~ ~ a s s e r t i o n

(which we

shall

nameQl)

i s

Ql:(MARY

HIT JOHN

ROCK)

which

translates

into

the

f o l l ~ i n g

triples:

<Q1

PRED

HIT>

(01

SUBJ

MARY>

4 1

OBJ

JOHN>

<Q1

INST

ROCK,

Workspace

(WS)

The

Workspace is

the

model's representation

for

that information

which

the

participant i s activcly using,

This

memory corresponds roughly

ta a model

of

the

participant's focus

of

attention.

W h i l e

the

L'TM

i s

static during the operation

ofthe model

(we are

not

attempting

t o

simulate

learning),

the

WS

i s

extremely volatile,

with

elements

(activations)

coming

into

and out

of

focus

c ~ t i n u o u s l y .

All

incoming sensations

(i.e.,

utterances) appear

in

the

WS,

as

do

all augmentations of

the

participant's knowledge and goal statc.

The

representational

format

of

the

WS

i s

the

same

a sin

LTM.

Each

node

in the WS

isa

token

(copy)

of

somenode

in

LTM.

Whenever

someprocess

determines

that the

model's

attention

(WS)

should

include

a

token

of

a

specific node

(C) from

LTM,

a

new node(A)

i screated

by copying

C

and

this

new node

i s

added

to

the WS. A

i s

referred

to as

an

a r t l r , n t l n n n ( r a n r l i h r , a i w -

<A

I A Q

C>

This

rcprescntatim providcs

the

associative

links

between

an object i n attention,

and

the

A

Modcl of DialogueThis

module

produces activations representing each successive utterance to beprocessed. These rcprcscntations are generated from

the

surface string usinga

standard

ATN

Grammar similar to those developed by Woods(19701 and

Norman, Rumelhart,fir

t h e LNR Research Group(1975).

We use a case grammar represeniation, w i t h each utterance spccificd as a main predicatewith a

set of parameters. Bccausc t h i smodule i s a conventional parser whose implementation i s well understood, we hove so far- p r o d u c e d hand parses of the input utterances, following an

ATN

grammar.P r o t c u s

This i s a sprcodine activation mechanism, which modifies thc activation of

conccpts

spccificd as r c l a t c d i n

LTM

whenevera

givcn c o n c ~ p t bccomcs active. This mcchanism p r o v i d e s a w a y to intcgratc top-down and bottom-up processing w i t h i n a uniform f r a m e w o r k (Lcvin, 1976). The Dial ogue-Game iilodel uses Protcus to activate a conccpt, given tha a number of closcly relatcd conccpts (Componcnts, fcaturcs, instances, etc.) arc active.I 9

Protcus opcratcs on

all

c u r r w t activations t o modify their salience", a numbcrassociated with each activation that generally represents the importance or rclcvancc of

t h e

conccpt. Two kinds of influence relations can existbctwccn

conccpts: c x c i t c orinhibit. I f an e x c i t e r e l a t i ~ n exists, then Protcus increases the salience af the

activation of that concept i n proportion to the saliencc of the influencing conccpt. The higher the salience of an activation, the larger i t s influence on directly r e l a t e d conccpts.

I f an inhibit relation i s spccificd. then Process decreases the salience of the activation

of

the neighboring

conccpt.Match

TI- is P r o c c x i idkntifics conccpts in LTM t h a t arc congruent to cxistinc activationr.

The Diologuc-Game Modcl conthins a numbcr of cquivalencc-like relations, which Mal'ch

u s e s to idcntify a conccpt in

LTM

as r c p r c s c n t i n ~ thc same thing as an activation of somo~ccrningly

different

concept. Oncethis

equivalent conccpt is found,i t

i s activated.Dcpcnding on how

this

conccpti o

dcfincd inLTM, i t s activation may havo

cffects. on o t h c r processes (for cxamplo, i f thc canccpt i s part of a rulc, Dcducc may bo invoked).Match

can

be v i c w c d as an attcrnpt to find an activation ( A ) i n WS and a Concc!pt(C)

A

Model

of Dialoguet o find a form of cquivalencc relationship between A and C, w i t h o u t d e l v i n g i n t o t h e i r s t r u c t u r e at

all.

Only i f this fails arc t h e i r respective substructures examined. I n t h ssccond

case, thes a m e

match which was attempted. at t h e t o p l e v e l i s t r i e d b c t w c c n c o r r e s p o n d i n gsubparts

of A andC.

Match

proceeds in f i v e steps:1. I s i t alrcady k n o w n that A i s an activation of C? I f so, t h e match ferminates

with a

p o s i t i v e conclusion,2.

Is

there any o t h e r activation (A7j, and/or conccpt (C') such that A"is k n o w n t o bc a view of A, C 1s known ta bc a kind of C', and A' i s k n o w n(by

step 1) to bc an actlvation of C'? The relations (i.. i s a v i e w of ...) gnd (... isba kind of ...) r c p r e s c n t stored relations between p a i r s of activations 1 and' concepts,r c s p c c t i v c l y . One concept "is a kind of" another conccpt r e p , ~ ~ ~ , l t s , a s ~ p c r c l a s s inclusion, t r u a f o r

all

t i m c a n d cdntexts. '(Whdever else h e mightbe, J o h n i s a k i n d o f

huma'n

being:) On the other hand, one activation may be "aview of" another only under certain circumstances--a conditional, o r tactical

relationship.

Undcr diffcrent.conditions, if i s appropriate to v i e w John as a Husband, Father, Child; Hcl p-seeker, Advice-giver, e tc,3. A l i s t of matched pairs of activations and concepts reprcscnt c o r r c s p o n d c n c c s found

el

scwhmc,

w i t h w h i c h match must be consi stcnt. (N.B.: t h i s Match, as we w i l l see later,may

be i n service of anothcr Match galled' o n siructuros containing t h e current A andC.)

I fthc

p a r [A,C] i s a matchcd pair, then these t y o have been previously found t o match,.so wemay

hcrc

concl'udo

the same thing and Match exits,4. On the other hand, i f t h e r e i s either an X or a Y such that [A,X]

(or

[Y,C]) i s a m a t c h c d pair, then replace this match with an attempt to match C and X(or A

and Y).

5. Finally, i f t h e matchahas ncither succeeded nor failed by this pqint, !hcn

Match i s called r e c u r s i ~ ~ l y on all corresponding ~ u b p a r t s of A ahd C, p a i l ~ ~ i s c .

That

is, c . ~ . , i f A and C have only t h r c c s u b p a r t s i p common (soy, SU3J, 013J and PRED)t h n

Match((SUBJ of A),(SUBJ of C)), Match((OBJDof A),(OBJ of C)) and ~ a t c h ( ( ~ ~ € ~ of A ) , ( P ~ E O of C)) arc attempted. Only i f all ofthcsc subordinate matches succeed i s t h e top-level Match said t o succccd.

Clearly, f o r structures of significant complexity, Match may eventually call itc,clf rccursivcly, t o an arbitrory depth. However, since each subordinate call i s on a strictly

A

Madcl

of DialogueOur

experiencehas

shown usthat this

type of mechanism plusa

collection ofrewrite rules enable us to eventually map

a

wide variety of inputparsing

structirrcsto

pre-stored, abstract knowledge structures, in a way that a significant aspect o f t h e i r intended meaning has been assimilated in the process.

Dcducc

This opcratcs to carry out a rule when that rule has become active. Rules are of t h e form (Condition)->(Action), and Dcduce scnscs thc activity of a rule and applies the

r u l e by activating the concept for the action. Whatcver corresponocnces w e r e evolved in the coursc.of cccating the activation of the condition (left) half of i h e rule are c a r r i e d o v e r into thc activation of the action (right) half. The combination of Match and Dcduce

a em.

gives

us

t h e capability o f a production syctThc operation of Dcducc i s relatively simple. I t i s called oniy

when

drule

i s a c t i v e i nt h e WS.

Dcducc attempts tomatch

the

left half of this rule w i t h some other activation i n the WS. (This h a s ty-pically already been done by match.) Assuming this i s accomplished, Dcduce c r e s t e t an ac,tivalion of the right half of the rule, substi luting in the activation f o rall

subparts for which thcke are correspondences with the i c f t half.Once a Dialogue-game

has

been activated (by Protcu.,) as possibly thecomrnunrcation f o r m being bid for a dialogue, the Dialogue-game

Manager

usesi t

t o guide t h c assimilation of successive utterances of t h e dialogue, through four stages:1. establish t h e Parameter values and verify that no Specification i s

contradictcd,

2. cstabli

;h

olhcrwi sc unsupported Specifications as assumptions,3.

cstrrblish the Components a s goal$ ofthc

participanfs,4. dctcct t h e c i r c u m s t a n c c ~ which indicate

that

the Dialogue-game is.terminating

and represent thc conscquenccs of this.Thc first two o f thesc phaces h s p p c n in p a r a l l e l . Whcn the

Manager

a c c e s s e sA

M o d e l of Dialogueperiodically c h c c k c d i n the hope that later activity

by the

Managerwill

lead

t othe

creation

of appropriate activations.F o r each of t h e Specifitations,

a check

i s made to determinei f

i t already

has an activation inWS.

(In most cases, the activation of some of these Specifications will haveled

t othe

activity of the Dialogue-game itself.) The Specifications having activations n e e dno

further attention.

For

all

remaining Spcc,ifications, activations are created substituting for t h e Parametcrs as determined above. Atthis

stage, the Dialogue-game Manager callsP r o t c u s to determine the stability of thcso new activations. Any

new

activation w h i c h contradicts existing activations willhave

its level of activity sharply reducedby Proteus.

I f

t h i s happens,the

Dialogue-game Manager concludes that some of t h e necessary preconditions f o r the gamedb

not hold (are i n conflict with current understanding) and that t h i s particular game shouldbe

abandoned. Otherwise, the new activaticns stand as new knowledge, following fromthe hypothesis

that t h e chosen game i s appropriate,The

Dialogue-gamehas

now

been successfully entered: t h e Manager sets up t h e t h i r d phase, creating activations of the Dialogue-game's Components, w i t h a p p r o p r i a t e substitutions.(By

this time, any unresolvedParameters

maywell

have -activations, permitting t h e i r resolution.)This

sets up all of the game-specific knowledge and goals f o rboth

participants.Finally, the Manager detects that one of the Specifications no longer appears to hold. This signals

the impending

termination ofthe

Dialogue-game. I n fact, t h e utterancewhikh

contai'ns this information i sa

bid to terminate.

At t h i s point, i f t h e p a r t i c i pants7 initial goals are satisfied(thus

contradicting the Specification which c a l l s f o r t h e prcsence of those goals)the

interaction ends "successfully". Otherwise, t h e Dialogue-game i s terminated for some other reason (e.g., one participant's unwillingness o r inability t ocontinue)

and

would generallybe

regarded

asa

"failure". These consequences are infcrred by the Manager and added tothe WS.

When a Dialogue-gamehas

terminated, i t s salience goes to zero and i t i s removed from theWS.

Pronoun Proccsscs