aDepartment of Social Work and Social Administration, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong; and bShanghai Children’s Medical Center, Shanghai, China

Ms Xie conceptualized and designed the study, extracted and analyzed data, wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, and significantly contributed to revision; Drs Chan, Chan, and Ji critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and significantly improved manuscript quality; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

DOI: https:// doi. org/ 10. 1542/ peds. 2017- 2675 Accepted for publication Jan 25, 2018

To cite: Xie Q-W, Chan C.H.Y., Ji Q, et al. Psychosocial Effects of Parent-Child Book Reading Interventions: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20172675 CONTEXT: Parent-child book reading (PCBR) is effective at improving young children’s

language, literacy, brain, and cognitive development. The psychosocial effects of PCBR interventions are unclear.

OBJECTIVE: To systematically review and synthesize the effects of PCBR interventions on

psychosocial functioning of children and parents.

DATA SOURCES: We searched ERIC, PsycINFO, Medline, Embase, PubMed, Applied Social Sciences

Index and Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, Family and Society Studies Worldwide, and Social Work Abstracts. We hand searched references of previous literature reviews.

STUDY SELECTION: Randomized controlled trials.

DATA EXTRACTION: By using a standardized coding scheme, data were extracted regarding

sample, intervention, and study characteristics.

RESULTS: We included 19 interventions (3264 families). PCBR interventions improved the

psychosocial functioning of children and parents compared with controls (standardized mean difference: 0.185; 95% confidence interval: 0.077 to 0.293). The assumption of homogeneity was rejected (Q = 40.010; P < .01). Two moderator variables contributed to between-group variance: method of data collection (observation less than interview;

Qb = 7.497; P < .01) and rater (reported by others less than self-reported; Qb = 21.368;

P < .01). There was no significant difference between effects of PCBR interventions on psychosocial outcomes of parents or children (Qb = 0.376; P = .540).

LIMITATIONS: The ratio of moderating variables to the included studies limited interpretation of

the findings.

CONCLUSIONS: PCBR interventions are positively and significantly beneficial to the psychosocial

functioning of both children and parents.

Psychosocial Effects of

Parent-Child Book Reading

Interventions: A Meta-analysis

Qian-Wen Xie, MSW, a Celia H.Y. Chan, PhD, a Qingying Ji, MD, MSW, b Cecilia L.W. Chan, PhDaThere is extensive literature in which researchers support the positive contributions of parent-child book reading (PCBR) experiences to early child development, especially language and literacy development.1, 2

PCBR during early childhood is also a strong predictor of children’s brain

development3 and later academic

achievement.4 Given the benefits of

PCBR, a Policy Statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that it is a responsibility of pediatric health care providers to encourage parents to read with their children as early as possible.5

A large number of PCBR intervention programs have been implemented worldwide, such as the Reach Out and Read program in the United States and the Home Interaction Program for Parents and Youngsters in Australia. PCBR interventions have been suggested as an important tool in closing the achievement gap between families of high and middle socioeconomic status (SES) and

families of lower SES.6 However, the

lack of systematic evaluation of the effects of PCBR interventions has

been a major criticism.7

In the past, research on the effects of PCBR has been limited to the field of early childhood education. Recently, an increasing number of scholars have suggested looking at the benefits of PCBR in a broader way, rather than exclusively focusing on literacy or language development of children.8, 9 To date, there have been

few studies in which researchers have studied the psychosocial effects of PCBR on children, and their findings are inconsistent.10–14

Moreover, the role of parents as beneficiaries in PCBR interactions has been often ignored, despite some evidence that PCBR interventions could not only improve parenting competence15, 16 and parent

self-esteem17 but also reduce parent

stress and depression.18, 19

Although PCBR has been recognized as an interactive activity between

parents and children, limited research has been focused on its impact on the quality of parent-child relationships. In the 1990s, Bus et al20

demonstrated an association between PCBR activities and child-parent attachment relationships, whereas more recent studies have revealed mixed results.13, 21

Researchers have explored the predictors that might moderate the effectiveness of PCBR interventions in improving the language or literacy development of children. There are inconsistent findings from this research, with some evidence for children’s age, 22, 23

sex, 24 race and/or ethnicity, 1 and

at-risk status25 and parents’ sex, 26

educational background, 27 and SES

as predictors28; however, authors

of other studies have suggested that PCBR was equally effective despite children’s age, ethnicity, at-risk status, 29 and family’s SES.16 There

is also the school of thought that different characteristics of PCBR interventions might produce different

effects.2 For example, researchers

suggest that children could benefit more from interventions by using dialogic reading (DR) techniques that emphasize high levels of adult-child interaction than traditional book reading.25, 30

PCBR interventions emphasize parent-child interactions and family empowerment rather than directly targeting developmental problems. It is therefore important to understand how well PCBR interventions work in enhancing psychosocial outcomes related to parent-child interactions. Psychosocial functioning

encompasses various aspects of psychiatric, psychological, and social competence and well-being, and it refers to the ability of self-caring or working, a positive evaluation of self and life, and a positive well-being received from meaningful relationships or activities.31, 32

Psychosocial functioning has usually been measured by symptom

severity31 (eg, depression, 33 stress

symptoms, 34 behavioral problems, 35

etc), personal competence or skills31

(eg, personal performance,

social-emotional adjustment, 36 parental

practices37), and sociocultural

expectancies31 (eg, quality of life36

and parent-child relationships38).

There is no synthesis of the available research on the impact of PCBR interventions on the psychosocial functioning of children and parents. Two research questions underpinned the meta-analysis reported in this article: (1) do PCBR interventions positively affect the psychosocial functioning of both children and parents, and (2) to what extent are these intervention effects moderated by sample characteristics, study characteristics, and intervention characteristics?

METHODS

The meta-analysis was reported on the basis of the PRISMA reporting standard.39

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included in this meta-analysis if the following were included:

1. a PCBR intervention group that received structured training, supportive materials, or other reading-related services for encouraging parents to read books with their children was compared with a control group that did not; 2. a randomized controlled trial

(RCT) design was used; 3. outcome variables were

contained that were measures of psychosocial functioning of children or parents;

4. sufficient empirical information to calculate effect sizes was provided; and

Information Sources and Search Strategy

Studies were identified by a comprehensive literature search through 10 electronic databases, including ERIC, PsycINFO, Medline, Embase, PubMed, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, Family and Society Studies Worldwide, and Social Work Abstracts. Search dates were from the date of inception to June 2017. Search terms comprised the following synonyms: (reading or literacy) and (parent-child or family or home) and (random* or experiment* or RCT). In addition, the reference lists of previous reviews1, 2, 25, 29, 40–43

were hand searched for relevant intervention studies.

Study Selection and Quality Assessment

All records were exported to EndNote software for the management of studies and elimination of

duplicates.44 Titles, abstracts, and full

texts of the remaining studies were scanned, according to the selection criteria. To assess the quality of each study, 2 investigators independently calculated the methodology

quality score on the basis of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting

Trials (CONSORT) 2010 checklist.45

The checklist contained 10 items regarding the research method, such as trial design, participants, interventions, outcomes, sample size, randomization, blinding, and statistic methods. The score was coded as 1 for 1 item. A study received the highest score (10) when it satisfied all criteria.

Data Collection

By using a standardized coding scheme (Table 1), data items were extracted regarding sample characteristics, intervention characteristics, or study

characteristics. Because multiple outcome measures were reported

in this literature review, 2 study characteristics (ie, rater and method of data collection) were coded at the outcome domain level instead of the study level. We were interested in the effects of independent PCBR interventions. When researchers in a study compared 2 independent PCBR intervention groups to 1 control group, we treated the 2 independent PCBR interventions as 2 separate studies. Also, we equally divided the sample of the control group of the original study into 2 groups to prevent participants from being counted more than once. Similar procedures were used in previous meta-analysis studies.25, 46

Two raters independently coded a random sample of 20% of the

included studies to estimate the interrater reliability of the study codes. We calculated Cohen’s κ by using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY), in which a high level of agreement between the raters was revealed (unweighted

κ = 0.88). After all coding

inconsistencies between coders were resolved by discussion, 1 rater coded the remaining 80% of the studies.

Synthesis of Results

Calculations for the meta-analysis were performed by using the

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA)

software.47 For each intervention,

we computed an effect size as a standardized mean difference between the mean of a PCBR

TABLE 1 Coding Scheme

Variable Scale Interrater

Reliability

(A) Sample size No. participants in intervention and control groups in the posttest

κ = 0.692

(B) Method score Scores calculated according to the CONSORT 2010 checklist κ = 0.333 (C) Child’s age Mean age of children at onset of study, mo κ = 0.667

(D) Child’s sex Percentage of girls κ = 0.692

(E) Child’s race and/ or ethnicity

Percentage of ethnic minorities. 1 = predominantly white; 2 = predominantly minority

a

(F) Child’s at-risk status

0 = not at risk; 1 = at risk (had low incomes, had less-educated mothers, had behavior problems, had language

delay, or lived in a disadvantaged community)

a

(G) Participated parents

1 = mothers only; 2 = mix (% of mothers) a

(H) Parental education

1 = low; 2 = mix a

(I) SES 1 = low; 2 = mix a

(J) Country 1 = United States; 2 = other than United States a (K) Delivery context 1 = home; 2 = school; 3 = primary care center or hospital; 4 =

others (eg, library, Head Start center, or laboratory)

a

(L) DR 0 = no; 1 = yes a

(M) Psychosocial component

0 = no; 1 = yes a

(N) Duration, mo Period from pretest to posttest: numerical (1 school y = 10

mo) κ

= 0.692

(O) Structured training

0 = no; 1 = yes a

(P) Dosage of training

Numerical a

(Q) Delivery method 1 = individual; 2 = group κ = 0.500

(R) Home visits 0 = no; 1 = yes a

(S) Staff quality 1 = professionals (eg, people with a degree in early education or speech pathology); 2 = semiprofessionals (eg, social

workers, nurses, physicals, volunteer readers)

a

(T) Rater 1 = self; 2 = other a

(U) Method of data collection

1 = interview; 2 = observation a

intervention group and a control

group at posttest by using Cohen’s

d.47 When an intervention contained

more than 1 outcome domain, we treated each outcome domain as an independent correlate for comparing the effect sizes of different outcome domains. We averaged the effect sizes within the study if 1 outcome domain was measured by multiple

tests.47 To avoid including more

than 1 effect size per construct per sample, we aggregated the effect sizes of different outcome domains by means of averaging to generate a combined effect size47, 48 called

“total psychosocial functioning.” We

converted each study-level treatment effect to a standardized mean difference for calculating an overall effect size of all included PCBR interventions on the psychosocial functioning of both children and parents. The precision of effect sizes was addressed by the 95% confidence interval (CI). A combined effect is considered significant if the CI does not include 0. The Q statistic was used to test the homogeneity across studies, and significant Qs imply heterogeneity. I2 was used to

measure the degree of inconsistency between studies.

Studies were grouped by relevant characteristics to test the impact of moderator variables. This analysis used the coding developed for studies, samples, and interventions (Table 1). These codes were applied as moderator variables for analysis of whether these characteristics were related to the effects of PCBR interventions on psychosocial outcomes of children and parents. The analyses of the impact of the data collection method and rater were conducted at outcome domain level. Other moderator variables were analyzed at study level.

Publication Bias

Omitting unpublished studies from this meta-analysis could bias the estimates of the effect of PCBR

interventions because studies with significant findings might have more opportunities to be published in peer-reviewed journals than studies with nonsignificant findings. The CMA software was also used to test publication bias.47 Visual inspection

of the funnel plot was used to address the potential impact of publication

bias.49 The Begg and Mazumdar’s50

rank correlation test and Egger’s

linear regression method51 were

used to quantify the bias captured

by the funnel plot. The Rosenthal’s

fail-safe number was calculated, which reflects the number of missing studies with null or nonsignificant results that would have to be included in the meta-analysis before

the P value becomes nonsignificant.47

We used the trim and fill approach to calculate the unbiased effect size if there appeared to be asymmetry

around the point estimate.52

Subgroup Analyses

We treated outcomes from parents and children separately, as 2 subgroups, for comparing the effect sizes of psychosocial functioning for different groups of recipients (ie, children versus parents). In each study, we aggregated effects within a given intervention to generate a single effect size called “child psychosocial functioning” or “parent

psychosocial functioning.”

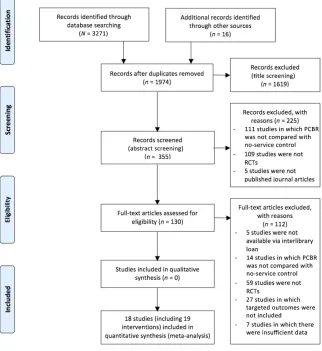

RESULTS Study Inclusion

The electronic database search yielded 3271 records. Hand searching reference lists of the earlier published reviews yielded 16 additional studies related to PCBR. After removing duplicates, 1974 studies remained. After further consideration of title, abstract, and full text, a total of 18 studies12–14, 16, 18, 19, 53–64 met

the selection criteria and were included in the meta-analysis. In Fig 1, we present the study inclusion process.

In 1 of the 18 studies, 2 independent intervention groups were separately

compared to 1 control group.14

We were interested in both interventions: one was a book gifting intervention, which provided free books to parents to encourage parents to read with their child; whereas the other included parental training related to PCBR. Therefore, we coded the 2 interventions as 2 separate studies. We labeled 1 intervention-control pair as Study 1 and the other as Study 2. Thus, 19 independent interventions reported in 18 relevant studies were assessed in the present meta-analysis.

Outcome Measures

Outcome measures of the

psychosocial functioning of children included the following:

1. social-emotional adjustment, assessed with the Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional

Assessment65 and the Parent

Rating Scales from the Behavior Assessment System for Children,

Second Edition66 and the Social

Competence Scale67;

2. behavior problems, assessed with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, 68 the Parental

Account of Child Symptoms

questionnaire, 69 and the Eyberg

Child Behavior Inventory70;

3. quality of life, assessed with the Pediatric Quality of Life

Inventory71; and

4. reading interest, assessed with the

Brief Reading Interest Scale60 and

a self-designed questionnaire. Psychosocial functioning outcome measures for parents included the following:

1. stress and/or depression,

assessed with the Parenting Stress Index72, 73 and the Beck Depression

Inventory–Revised74;

Involvement Questionnaire, 77 and

a self-designed questionnaire; 3. parent-child relationship,

assessed with a self-designed questionnaire; and

4. parental attitude to reading with child, assessed with the Parent Reading Belief Inventory, 78 and a

self-designed questionnaire.

Study Characteristics

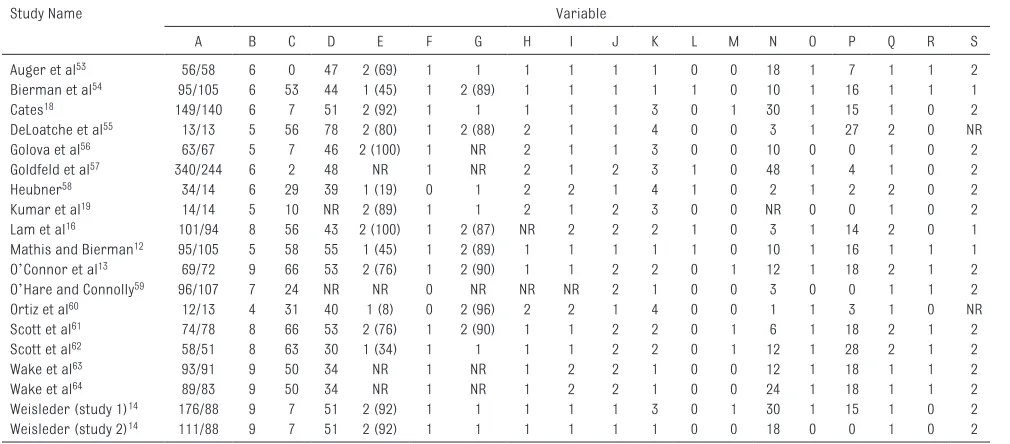

The characteristics of studies, participants, and interventions are presented in Table 2.

Characteristics of Studies

Of the 18 studies, only 3 were published earlier than 2010.56, 58, 60

Sample sizes across 19 interventions ranged from 15 to 584 individuals. Although all interventions included

were evaluated by using RCTs, the scores of their methodological quality ranged from 4 to 9.

Characteristics of Participants

Nineteen interventions (N subjects =

3264) were provided to different types of children and families. Ten interventions14, 18, 19, 53, 56–60

targeted infants and/or toddlers (0–3 years old; n = 1856) and 9 interventions12, 13, 16, 54, 55, 61–64

were tested with preschool-aged children (3–6 years old; n = 1408). The percent of girls participating ranged from 35% to 78%. Of the 15 studies in which researchers reported sufficient information of

participants, ∼44% were members

of ethnic minorities. The majority of the interventions were delivered to children living in at-risk situations

(eg, having low incomes, less-educated mothers, behavioral problems, language delay, or living

in disadvantaged communities).*

Mothers were the most common parent included in the interventions. Parents were reported as having low education in 11 interventions (n = 2024).12–14, 18, 53, 54, 61–64

There were 13 interventions provided to families of low SES (n = 2436).12–14, 18, 19, 53–57, 61, 62 Ten

interventions12, 14, 18, 53–56, 58, 60 were

conducted in the United States (n = 1495), and the other 913, 16, 19, 57, 59, 61–64 were also from

high-income countries or areas such as the United Kingdom, Australia,

and Hong Kong (n = 1769).

Characteristics of Interventions

Interventions were conducted in a range of contexts, including primary care centers or hospitals,

participants’ homes, schools, and

communities (eg, library, Head Start center, or laboratory). DR techniques were used in 5 interventions (n = 1227).12, 16, 54, 57, 58 Five

interventions combined PCBR activities with other psychosocial components, such as parenting or child behavior programs

(n = 955).13, 14(study 1), 18, 61, 62 The

majority of interventions provided parents with structured training on

how to read with children (n = 2704).

Dosage of training ranged from 2 to 28 sessions. Services were delivered to families by using individual models (n = 2593) or group models (n = 671). Nine interventions also delivered home visit services to families (n = 1475).12, 13, 53, 54, 61–64 Only 3

interventions employed professionals (eg, people with university degrees in early education or speech pathology) to deliver services (n = 595).12, 16, 54

The duration of studies (from pretest to posttest) varied considerably. The longest study lasted for 48 months

* Refs 12– 14, 16, 18, 19, 53– 57, 61–64. FIGURE 1

whereas the shortest one lasted 1 month.

Synthesis of Results

The random effect sizes pooled by all the outcomes for each study are presented in Fig 2. There was considerable variability in the effect sizes reported in the included studies. Seventeen interventions affected children’s and parents’ psychosocial functioning positively, and negative impacts were demonstrated in 2 interventions. Combining results from 19 studies yielded a weighted mean effect on general psychosocial functioning of children and parents

of d = 0.185 (95% CI: 0.077 to 0.293),

which is a small effect size79 of

the total psychosocial functioning. The results of z tests (z = 3.355;

P = .001) revealed that the overall

effect size differed significantly from 0. Thus, the interventions included in this meta-analysis had a small but statistically

significant effect on the psychosocial outcomes of children and parents.

The statistically significant

Q statistic of 40.010 (P = .002) indicated that the differences among the effect sizes were due to heterogeneity rather than participant-level sampling error.39 The I2 value (I2 = 55.011)

indicated that ∼55% of total variance among studies was due to heterogeneity.

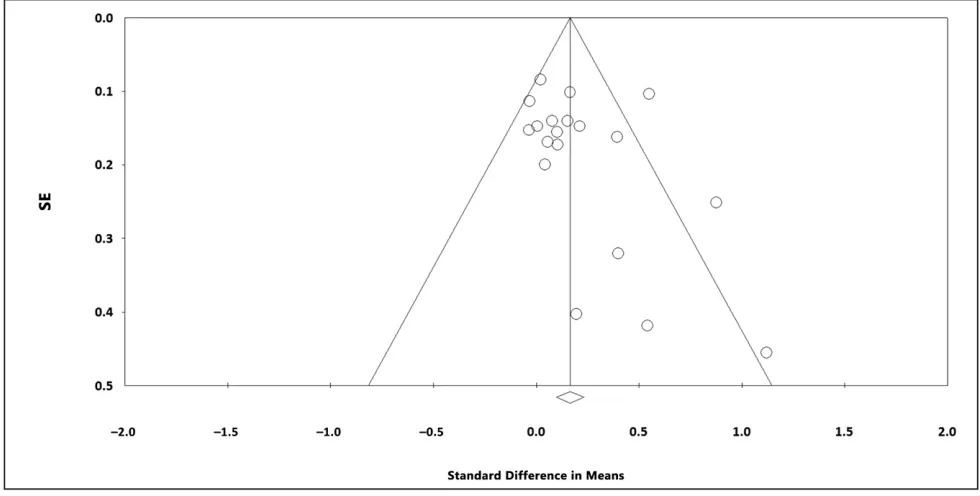

Publication Bias

The CMA software created a funnel plot (Fig 3) of any effect size index on the x-axis by the SE on the y-axis, which visually assessed the possibility of publication bias. Most studies were distributed symmetrically around the combined effect size. Studies at the bottom are clustered toward the right-hand side of the graph, making the effect size bigger than the unbiased effect size. For the rank correlation test, Kendall’s τ is 0.345 (P = .019). For Egger’s test, the intercept (b) is

1.289, with a 95% CI from −0.522

to 3.099 (P = .076). The test of

Egger’s regression and Begg and

Mazumdar’s50 rank correlation

revealed obscure asymmetry in the funnel plot. The classic fail-safe number indicated that 119 additional studies with null or nonsignificant results needed to be added to overturn these significant results negatively. Under the random effects model, the unbiased effect size was 0.174, slightly smaller than 0.185, which indicates that there is a tiny gap between the real effectiveness and the calculated effectiveness.

Explaining the Variability in Effect Sizes

Because the assumption of homogeneity between studies was rejected, further analysis was undertaken to assess whether the characteristics of the studies could account for the variance. Among the 21 variables listed in Table 1 that were analyzed for their impact as moderator variables, only 2 contributed significantly to

TABLE 2 Characteristics of Participants and Interventions

Study Name Variable

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S

Auger et al53 56/58 6 0 47 2 (69) 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 18 1 7 1 1 2

Bierman et al54 95/105 6 53 44 1 (45) 1 2 (89) 1 1 1 1 1 0 10 1 16 1 1 1

Cates18 149/140 6 7 51 2 (92) 1 1 1 1 1 3 0 1 30 1 15 1 0 2

DeLoatche et al55 13/13 5 56 78 2 (80) 1 2 (88) 2 1 1 4 0 0 3 1 27 2 0 NR

Golova et al56 63/67 5 7 46 2 (100) 1 NR 2 1 1 3 0 0 10 0 0 1 0 2

Goldfeld et al57 340/244 6 2 48 NR 1 NR 2 1 2 3 1 0 48 1 4 1 0 2

Heubner58 34/14 6 29 39 1 (19) 0 1 2 2 1 4 1 0 2 1 2 2 0 2

Kumar et al19 14/14 5 10 NR 2 (89) 1 1 2 1 2 3 0 0 NR 0 0 1 0 2

Lam et al16 101/94 8 56 43 2 (100) 1 2 (87) NR 2 2 2 1 0 3 1 14 2 0 1

Mathis and Bierman12 95/105 5 58 55 1 (45) 1 2 (89) 1 1 1 1 1 0 10 1 16 1 1 1

O’Connor et al13 69/72 9 66 53 2 (76) 1 2 (90) 1 1 2 2 0 1 12 1 18 2 1 2

O’Hare and Connolly59 96/107 7 24 NR NR 0 NR NR NR 2 1 0 0 3 0 0 1 1 2

Ortiz et al60 12/13 4 31 40 1 (8) 0 2 (96) 2 2 1 4 0 0 1 1 3 1 0 NR

Scott et al61 74/78 8 66 53 2 (76) 1 2 (90) 1 1 2 2 0 1 6 1 18 2 1 2

Scott et al62 58/51 8 63 30 1 (34) 1 1 1 1 2 2 0 1 12 1 28 2 1 2

Wake et al63 93/91 9 50 34 NR 1 NR 1 2 2 1 0 0 12 1 18 1 1 2

Wake et al64 89/83 9 50 34 NR 1 NR 1 2 2 1 0 0 24 1 18 1 1 2

Weisleder (study 1)14 176/88 9 7 51 2 (92) 1 1 1 1 1 3 0 1 30 1 15 1 0 2

Weisleder (study 2)14 111/88 9 7 51 2 (92) 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 18 0 0 1 0 2

between-group variance. These were the method of data collection (observation less than interview;

Qb = 7.497; P < .001) and rater (reported by others less than self-reported; Qb = 21.368; P < .001).

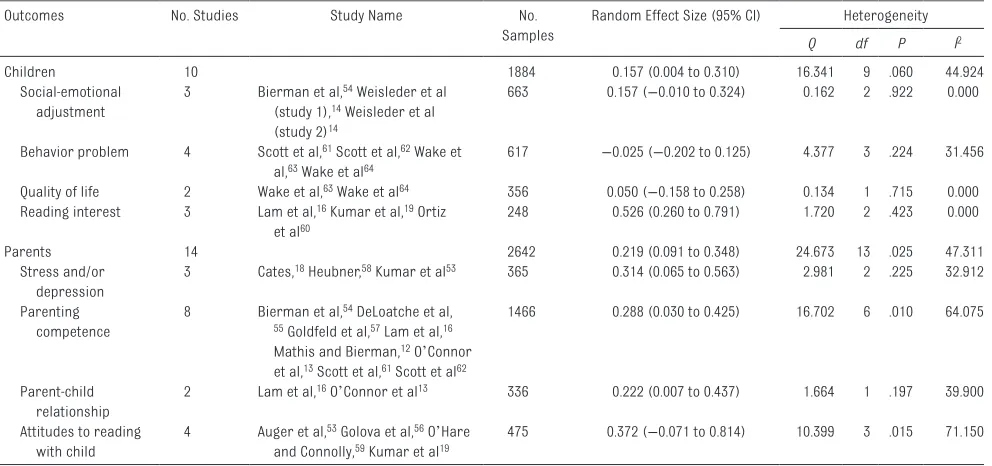

Subgroup Analyses

In 14 interventions, researchers assessed the psychosocial

performances of parents (n = 2642),

and in 10 studies, researchers assessed the outcomes of children

(n = 1884). Small effect sizes were found for parent psychosocial

functioning (d = 0.219; 95% CI: 0.091

to 0.348; Q = 24.673; P = .025) and child psychosocial functioning

(d = 0.157; 95% CI: 0.004 to 0.310;

Q = 16.341; P = .060). Although the

effect size of parents’ outcomes was

larger than children’s, there was no

significant difference in the effects of PCBR interventions on psychosocial outcomes of parents and children (Qb = 0.376; P = .540). Different

psychosocial outcomes of parents and children were examined and findings are presented in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

Summary of Evidence

PCBR is commonly considered as one of the most important activities

within the family context.28 Our

meta-analysis was undertaken in an attempt to assess the effects of PCBR interventions on psychosocial functioning in general. Combining the results of 19 interventions and representing 3264 families, our analysis produced a mean weighted

FIGURE 2

Random effect size for each study. df, degrees of freedom.

effect size that was small but significant (at 0.185). In our review, we suggest that PCBR interventions may be superior to control for improving the psychosocial functioning of both children and parents.

PCBR is a complex social process occurring within an interpersonal context, which supports a broad range of outcomes for both children and their parents.26, 27, 80, 81

Demonstrated in our synthesis is that PCBR interventions might

positively impact children’s

social-emotional competence, quality of life, and reading interest. Behaviors and responses of children may also impact the competence or well-being of parents. PCBR interventions might

be effective in improving parents’

parenting competence, attitudes to reading with their child, and the quality of their relationships with children. It may also assist in reducing their stress or depression. We found no statistically significant difference in the impacts of PCBR interventions on psychosocial outcomes of parents and children. Thus, prioritizing 1 group of

participants’ outcomes over another

(whether children or parents) may ignore the potential of PCBR interactions.8

In our review, we found that the psychosocial effects of PCBR were similar, despite the characteristics of participating children. Although age may impact the effectiveness of PCBR

interventions in improving children’s

acquisition of literacy, 40 PCBR

interventions appear to have similar psychosocial effects on both older

children (3–6 years old) and younger

children (0–3 years old). In contrast with previous research in which a

child’s sex was considered as an

important factor when interpreting

PCBR interactions, 24 our review

did not find that a child’s sex could predict the psychosocial effects of PCBR interventions.

In our review, we support that children who were socioeconomically or culturally disadvantaged might equally benefit from PCBR interventions as their counterparts. For example, we found that the psychosocial effects of PCBR were not dependent on the race and/or ethnicity of children, although it has been

indicated in previous research that white families might benefit more from PCBR activities than

minority families.1 Moreover,

in this review, we did not find support for the expected moderating effects of at-risk status of children (eg, having low incomes, less-educated mothers, behavioral problems, language delay, or living in a disadvantaged community) on the psychosocial effects of PCBR interventions. In fact, children living in at-risk status or from families of low SES or a minority ethnicity may need more reading-related support because they may have fewer educational resources than their counterparts. In many previous studies,

researchers have also shown the success of PCBR programs for children from high-risk families, such as children whose parents

were in prison, 82 children whose

mothers were teenagers, 19, 83

and children who were from

homeless families.84

In the current review, we found that the length of the study and dosage of PCBR intervention were not predictive of psychosocial

TABLE 3 Outcomes of the Effects of PCBR Interventions

Outcomes No. Studies Study Name No.

Samples

Random Effect Size (95% CI) Heterogeneity

Q df P I2

Children 10 1884 0.157 (0.004 to 0.310) 16.341 9 .060 44.924

Social-emotional adjustment

3 Bierman et al, 54 Weisleder et al (study 1), 14 Weisleder et al (study 2)14

663 0.157 (−0.010 to 0.324) 0.162 2 .922 0.000

Behavior problem 4 Scott et al, 61 Scott et al, 62 Wake et al, 63 Wake et al64

617 −0.025 (−0.202 to 0.125) 4.377 3 .224 31.456

Quality of life 2 Wake et al, 63 Wake et al64 356 0.050 (−0.158 to 0.258) 0.134 1 .715 0.000 Reading interest 3 Lam et al, 16 Kumar et al, 19 Ortiz

et al60

248 0.526 (0.260 to 0.791) 1.720 2 .423 0.000

Parents 14 2642 0.219 (0.091 to 0.348) 24.673 13 .025 47.311

Stress and/or depression

3 Cates, 18 Heubner, 58 Kumar et al53 365 0.314 (0.065 to 0.563) 2.981 2 .225 32.912

Parenting competence

8 Bierman et al, 54 DeLoatche et al, 55 Goldfeld et al, 57 Lam et al, 16 Mathis and Bierman, 12 O’Connor et al, 13 Scott et al, 61 Scott et al62

1466 0.288 (0.030 to 0.425) 16.702 6 .010 64.075

Parent-child relationship

2 Lam et al, 16 O’Connor et al13 336 0.222 (0.007 to 0.437) 1.664 1 .197 39.900

Attitudes to reading with child

4 Auger et al, 53 Golova et al, 56 O’Hare and Connolly, 59 Kumar et al19

475 0.372 (−0.071 to 0.814) 10.399 3 .015 71.150

effectiveness. There are other variables that were not assessed in the included studies that may be influencing factors, such as the contents and text features of books22, 24

and the quality of parent-child interactions.20, 24 Moreover, provision

of DR training may not have an impact on the general psychosocial effectiveness of PCBR interventions. It is suggested in the meta-analysis that shared reading as a meaningful interaction between children and parents rather than specific reading techniques might be the key to the positive psychosocial effects of PCBR interventions. We believe that PCBR is a low cost and simply adapted approach for any parent-child dyad, no matter what the circumstances.

Conducting this meta-analysis allowed us to assess the current state of the research on PCBR interventions. We found a limited number of studies that met the selection criteria. Future researchers should pay more attention to the quality of study design because many PCBR-related studies identified in our search were excluded because of not employing an RCT design. Also, validated scales were not commonly used to evaluate psychosocial effects of PCBR interventions, especially on the quality of parent-child relationships. PCBR is not only a process of communicating information or learning skills but also a socially created, interactive process. Using validated scales to assess its effects on parent-child relationships may improve our understanding about the dynamics of PCBR interactions. In our review, we also identified that only a limited number of the reported PCBR interventions involved fathers. Future PCBR interventions should be designed to attract the participation of fathers because of the importance of father-child interactions in the

development of children.85

Limitations

First, because of our strict inclusion criteria, we were able to include only a limited number of studies. The ratio of moderating variables to the included studies limits interpretation of the findings and potentially renders this review as an exploratory process. Second, dissecting interventions in the included studies was problematic because authors of some studies reported on interventions with combined reading and psychosocial components (eg, parenting programs and child behavior programs).13, 61, 62

It was therefore difficult to extract and conclude the role of PCBR components in these multiple interventions. Third, we identified and included a broad range of psychosocial outcomes from the included studies. For example, we included studies in which the effects of PCBR on reading interests of children and parental attitudes of reading with their child were assessed. To make sense of these different measures, we treated reading interest as personal competence of children and positive attitudes in reading with children as an important parenting competence. Whether the studies were similar enough to be combined may be questioned because of the various measures of psychosocial functioning included in the review. However, the goal of this review was to explore the pattern of psychosocial effectiveness of PCBR interventions by assessing psychosocial effectiveness of PCBR interventions in general. The method we used to calculate effect sizes

was suggested by Borenstein et al47

and has been also used in previous studies as well.43, 86 We recognized

the limitation and addressed the diversity by applying the random effects model and reporting the range of true effects.47 We also interpreted

the variability by testing the effects of moderator variables.

CONCLUSIONS

Exploring and assessing psychosocial effects of shared reading between parents and children allow us to extend the implications of PCBR interventions. A large number of family interventions have traditionally targeted behavioral problems of children instead of the interactions or relationships between parents and children. Because of the limited long-term efficacy of an individual-focused approach, more and more scholars have highlighted the importance of relationship-focused interventions.87, 88 Moreover,

psychosocial interventions targeting children have usually required traditional face-to-face therapies, which require intensive resources, especially including professional therapists. The delivery of these interventions has also posed challenges when children return to their families, if their families are not able to assist in the therapy.89 PCBR

programs can improve psychosocial functioning of children through empowering parents, which may be more cost-effective than face-to-face therapies for children alone.

In summary, suggested in our meta-analysis findings is that PCBR interventions might positively impact the psychosocial functioning of both parents and children. It seems prudent to consider the application of PCBR in improving the psychosocial well-being of families, especially those at high risk.

ABBREVIATIONS

CI: confidence interval CMA: Comprehensive

Meta-Analysis CONSORT: Consolidated

Standards of Reporting Trials DR: dialogic reading

REFERENCES

1. Manz PH, Hughes C, Barnabas E, Bracaliello C, Ginsburg-Block M. A descriptive review and meta-analysis of family-based emergent literacy interventions: to what extent is the research applicable to low-income, ethnic-minority or linguistically-diverse young children? Early Child Res Q. 2010;25(4):409–431

2. Sénéchal M, Young L. The effect of family literacy interventions on children’s acquisition of reading from kindergarten to grade 3: a meta-analytic review. Rev Educ Res. 2008;78(4):880–907

3. Mustard J. Experience-based brain development: scientific underpinnings of the importance of early child development in a global world. Paediatr Child Health. 2006;11(9):571–572

4. McElvany N, Artelt C. Systematic reading training in the family: development, implementation, and initial evaluation of the Berlin parent-child reading program. Learn Instr. 2009;19(1):79–95

5. Council on Early Childhood, High PC, Klass P. Literacy promotion: an essential component of primary care pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):404–409

6. Aram D, Fine Y, Ziv M. Enhancing parent-child shared book reading interactions: promoting references to the book’s plot and socio-cognitive themes. Early Child Res Q. 2013;28(1):111–122

7. Anderson J, Anderson A, Friedrich N, Kim JE. Taking stock of family literacy: some contemporary perspectives.

J Early Child Literacy. 2010;10(1):33–53 8. St. Clair R. Reading, writing, and

relationships: human and social capital in family literacy programs.

Adult Basic Educ Lit J. 2008;2(2):84–93

9. Terry M. Exploring the Additive Benefit of Parental Nurturance Training on Parent and Child Shared Reading Outcomes: A Pilot Intervention Study [dissertation]. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University; 2012 10. Aram D, Aviram S. Mothers’ storybook

reading and kindergartners’

socioemotional and literacy development. Read Psychol. 2009;30(2):175–194

11. Curenton SM, Craig MJ. Shared-reading versus oral storytelling: associations with preschoolers’ prosocial skills and problem behaviours. Early Child Dev Care. 2011;181(1):123–146

12. Mathis ET, Bierman KL. Effects of parent and child pre-intervention characteristics on child skill acquisition during a school readiness intervention. Early Child Res Q. 2015;33:87–97

13. O’Connor TG, Matias C, Futh A, Tantam G, Scott S. Social learning theory parenting intervention promotes attachment-based caregiving in young children: randomized clinical trial. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2013;42(3):358–370

14. Weisleder A, Cates CB, Dreyer BP, et al. Promotion of positive parenting and prevention of

socioemotional disparities. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20153239

15. Goldfeld S, Napiza N, Quach J, Reilly S, Ukoumunne OC, Wake M. Outcomes of a universal shared reading intervention by 2 years of age: the Let’s Read trial.

Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):445–453 16. Lam S-F, Chow-Yeung K, Wong BPH,

Lau KK, Tse SI. Involving parents in paired reading with preschoolers: results from a randomized controlled trial. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2013;38(2):126–135

17. Swain J, Brooks G, Bosley S. The benefits of family literacy provision for parents in England. J Early Child Res. 2014;12(1):77–91

18. Cates CB, Weisleder A, Dreyer BP, et al. Leveraging healthcare to promote responsive parenting: impacts of the video interaction project on parenting stress. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25(3):827–835

19. Kumar MM, Cowan HR, Erdman L, Kaufman M, Hick KM. Reach out and read is feasible and effective for adolescent mothers: a pilot study. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(3):630–638

20. Bus AG, Belsky J, van IJzendoorn MH, Crnic K. Attachment and bookreading patterns: a study of mothers, fathers, and their toddlers. Early Child Res Q. 1997;12(1):81–98

21. Lariviere J, Rennick JE. Parent picture-book reading to infants in the neonatal intensive care unit as an intervention supporting parent-infant interaction and later book reading. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2011;32(2):146–152 22. Fletcher KL, Reese E. Picture book

reading with young children: a conceptual framework. Dev Rev. 2005;25(1):64–103

23. Levin I, Aram D. Mother–child joint writing and storybook reading and their effects on kindergartners’

literacy: an intervention study. Read Writ. 2012;25(1):217–249

24. Clingenpeel BT, Pianta RC. Mothers’ sensitivity and book-reading interactions with first graders. Early Educ Dev. 2007;18(1):1–22

25. Mol SE, Bus AG, de Jong MT, Smeets DJH. Added value of dialogic parent– child book readings: a meta-analysis.

Early Educ Dev. 2008;19(1):7–26

Address correspondence to Cecilia L.W. Chan, PhD, Room 545, Jockey Club Tower, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong. E-mail: cecichan@hku.hk PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright © 2018 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. FUNDING: No external funding.

26. Pellegrini AD, Galda L. Joint reading as a context: explicating the ways context is created by participants. In: van Kleeck A, Stahl SA, Bauer EB, eds.

On Reading Books to Children: Parents and Teachers. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003:307–320

27. Bingham GE. Testing a Model of Parent-Child Relationships, Parent-Parent-Child Joint Book Reading, and Children’s Emergent Literacy Skills [dissertation]. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University; 2002

28. Williams KD. The Effects of an Interactive Reading Intervention on Early Literacy Development and Positive Parenting Interactions for Young Children of Teenage Mothers [dissertation]. Eugene, OR: University of Oregon; 2000

29. National Institute for Literacy. Developing Early Literacy: Report of the National Early Panel. 2008. Available at: https:// lincs. ed. gov/ publications/ pdf/ NELPReport09. pdf. Accessed February 8, 2018

30. Zevenbergen AA, Whitehurst GJ. Dialogic reading: a shared picture book reading intervention for preschoolers. In: van Kleeck A, Stahl SA, Bauer EB, eds. On Reading Books to Children: Parents and Teachers. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003:177–202 31. Gorwood P; The EGOFORS Initiative.

W04-02–psychosocial functioning (PSF)–definition and measurement.

Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(suppl 1):1 32. Ro E. Conceptualization of Psychosocial

Functioning: Understanding Structure and Relations With Personality and Psychopathology [doctoral thesis]. Iowa City, IA: The University of Iowa; 2010

33. Chen SY. Social Support, Stress, and Depression: Measurement and Analysis of Social Well-Being, Mental Health, and Quality of Life in a Context of Aging and Chinese Culture [doctoral thesis]. Oakland, CA: University of California; 1996

34. Villalobos GH, Vargas AM, Rondón MA, Felknor SA. Design of psychosocial factors questionnaires: a systematic measurement approach. Am J Ind Med. 2013;56(1):100–110

35. Roesch SC, Norman GJ, Merz EL, Sallis JF, Patrick K. Longitudinal measurement invariance of psychosocial measures in physical activity research: an application to adolescent data. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2013;43(4):721–729

36. Peuskens J, Gorwood P; EGOFORS Initiative. How are we assessing functioning in schizophrenia? A need for a consensus approach.

Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(6):391–395 37. Granner ML, Evans AE. Measurement

properties of psychosocial and environmental measures associated with fruit and vegetable intake among middle school adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(1):2–11

38. Kreitler S, Weyl Ben Arush M, eds.

Psychosocial Aspects of Pediatric Oncology. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons; 2004

39. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement.

PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097 40. Bus AG, van IJzendoorn MH, Pellegrini

AD. Joint book reading makes for success in learning to read: a meta-analysis on intergenerational transmission of literacy. Rev Educ Res. 1995;65(1):1–21

41. Mol SE, Bus AG. To read or not to read: a meta-analysis of print exposure from infancy to early adulthood. Psychol Bull. 2011;137(2):267–296

42. Kim JS, Quinn DM. The effects of summer reading on low-income children’s literacy achievement from kindergarten to grade 8: a meta-analysis of classroom and home interventions. Rev Educ Res. 2013;83(3):386–431

43. van Steensel R, McElvany N, Kurvers J, Herppich S. How effective are family literacy programs? Results of a meta-analysis. Rev Educ Res. 2011;81(1):69–96

44. Chen M, Chan KL. Effects of parenting programs on child maltreatment prevention: a meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2016;17(1):88–104 45. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D;

CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for

reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c332

46. Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F. Less is more: meta-analyses of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(2):195–215

47. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. West Sussex, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2009

48. Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical Meta-Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001

49. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test.

BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634 50. Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating

characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101

51. Sterne JA, Egger M, Smith GD. Systematic reviews in health care: investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ. 2001;323(7304):101–105 52. Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a

simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–463

53. Auger A, Reich SM, Penner EK. The effect of baby books on mothers’

reading beliefs and reading practices.

J Appl Dev Psychol. 2014;35(4):337–346 54. Bierman KL, Welsh JA, Heinrichs BS,

Nix RL, Mathis ET. Helping Head Start parents promote their children’s kindergarten adjustment: the research-based developmentally informed parent program. Child Dev. 2015;86(6):1877–1891

55. DeLoatche KJ, Bradley-Klug KL, Ogg J, Kromrey JD, Sundman-Wheat AN. Increasing parent involvement among Head Start families: a randomized control group study. Early Child Educ J. 2015;43(4):271–279

57. Goldfeld S, Quach J, Nicholls R, Reilly S, Ukoumunne OC, Wake M. Four-year-old outcomes of a universal infant-toddler shared reading intervention: the Let’s Read trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(11):1045–1052 58. Heubner CE. Promoting toddlers’

language development through community-based intervention. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2000;21(5):513–535 59. O’Hare L, Connolly P. A cluster

randomised controlled trial of

“Bookstart+”: a book gifting programme. J Child Serv. 2014;9(1):18–30

60. Ortiz C, Stowe RM, Arnold DH. Parental influence on child interest in shared picture book reading. Early Child Res Q. 2001;16(2):263–281

61. Scott S, O’Connor TG, Futh A, Matias C, Price J, Doolan M. Impact of a parenting program in a high-risk, multi-ethnic community: the PALS trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51(12):1331–1341

62. Scott S, Sylva K, Doolan M, et al. Randomised controlled trial of parent groups for child antisocial behaviour targeting multiple risk factors: the SPOKES project. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51(1):48–57 63. Wake M, Tobin S, Levickis P, et al.

Randomized trial of a population-based, home-delivered intervention for preschool language delay. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4). Available at: www. pediatrics. org/ cgi/ content/ full/ 132/ 4/ e895

64. Wake M, Levickis P, Tobin S, et al. Two-year outcomes of a population-based intervention for preschool language delay: an RCT.

Pediatrics. 2015;136(4). Available at: www. pediatrics. org/ cgi/ content/ full/ 136/ 4/ e838

65. Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Jones SM, Little TD. The Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA): factor structure, reliability, and validity. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2003;31(5):495–514

66. Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. Behavior Assessment System for Children. 2nd ed. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 2004

67. Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Initial impact of the Fast Track prevention trial for conduct problems: I. The high-risk sample. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(5):631–647

68. Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38(5):581–586

69. Taylor E, Schachar R, Thorley G, Wieselberg M. Conduct disorder and hyperactivity: I. Separation of hyperactivity and antisocial conduct in British child psychiatric patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1986;149(6):760–767 70. Boggs SR, Eyberg S, Reynolds LA.

Concurrent validity of the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory. J Clin Child Psychol. 1990;19(1):75–78

71. Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Seid M, Skarr D. The PedsQL 4.0 as a pediatric population health measure: feasibility, reliability, and validity. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3(6):329–341

72. Abidin RR. Parenting Stress Index. 3rd ed. Charlottesville, VA: Pediatric Psychology Press; 1990

73. Abidin RR. In: Zalaquett CP, Woods Lathan RJ, eds. Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources, 1st ed. Lanham, MD: University Press of America; 1997:277–292

74. Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1993 75. Fantuzzo J, Tighe E, Childs S. Family

involvement questionnaire: a multivariate assessment of family participation in early childhood education. J Educ Psychol. 2000;92(2):367–376

76. Dreyer BP, Mendelsohn AL, Tamis-LeMonda CS. Assessing the child’s cognitive home environment through parental report; reliability and validity.

Early Dev Parent. 1996;5(4):271–287 77. Webster-Stratton C, Jamila Reid M,

Stoolmiller M. Preventing conduct problems and improving school readiness: evaluation of the Incredible Years Teacher and Child Training Programs in high-risk schools. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(5):471–488

78. DeBaryshe BD, Binder JC. Development of an instrument for measuring parental beliefs about reading aloud to young children. Percept Mot Skills. 1994;78(suppl 3):1303–1311

79. Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155–159

80. Landry SH, Smith KE, Swank PR, Zucker T, Crawford AD, Solari EF. The effects of a responsive parenting intervention on parent-child interactions during shared book reading. Dev Psychol. 2012;48(4):969–986

81. Schwartz JI. An observational study of mother/child and father/child interactions in story reading. J Res Child Educ. 2004;19(2):105–114 82. Genisio MH. Breaking barriers with

books: a fathers’ book-sharing program from prison. J Adolesc Adult Lit. 1996;40(2):92–100

83. Scott A, van Bysterveldt A, McNeill B. The effectiveness of an emergent literacy intervention for teenage parents. Infants Young Child. 2016;29(1):53–70

84. Di Santo A. Promoting preschool literacy: a family literacy program for homeless mothers and their children.

Child Educ. 2012;88(4):232–240 85. Saracho ON. Fathers’ and young

children’s literacy experiences. Early Child Dev Care. 2008;178(7–8):837–852 86. Ng TK, Wong DFK. The efficacy

of cognitive behavioral therapy for Chinese people: a meta-analysis [published online ahead of print November 1, 2017]. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. doi: 10. 1177/ 0004867417741555

87. Rodenburg R, Wagner JL, Austin JK, Kerr M, Dunn DW. Psychosocial issues for children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;22(1):47–54

88. Scholten L, Willemen AM, Napoleone E, et al. Moderators of the efficacy of a psychosocial group intervention for children with chronic illness and their parents: what works for whom?

J Pediatr Psychol. 2015;40(2):214–227 89. Davis E, Conroy R. Psychological

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2017-2675 originally published online March 27, 2018;

2018;141;

Pediatrics

Qian-Wen Xie, Celia H.Y. Chan, Qingying Ji and Cecilia L.W. Chan

Meta-analysis

Psychosocial Effects of Parent-Child Book Reading Interventions: A

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/141/4/e20172675

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/141/4/e20172675#BIBL

This article cites 74 articles, 10 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

ub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/psychosocial_issues_s Psychosocial Issues

al_issues_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/development:behavior Developmental/Behavioral Pediatrics

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2017-2675 originally published online March 27, 2018;

2018;141;

Pediatrics

Qian-Wen Xie, Celia H.Y. Chan, Qingying Ji and Cecilia L.W. Chan

Meta-analysis

Psychosocial Effects of Parent-Child Book Reading Interventions: A

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/141/4/e20172675

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.