Assessing Quality Improvement in Health Care: Theory

for Practice

abstract

OBJECTIVES:To review the role of theory as a means to enhance the practice of quality improvement (QI) research and to propose a novel conceptual model focused on the operations of health care.

METHODS:Conceptual model, informed by literature review.

RESULTS: To optimize learning across QI studies requires the inte-gration of small-scale theories (middle-range theories, theories of change) within the context of larger unifying theories. We propose that health care QI research would benefit from a theory that describes the operations of health care delivery, including the multiplicity of roles that interpersonal interactions play. The broadest constructs of the model are entry into the system, and assessment and management of the patient, with the subordinate operations of access; recognition, assessment, and diagnosis; and medical decision-making (developing a plan), coordination of care, execution of care, referral and reassess-ment, respectively. Interpersonal aspects of care recognize the patient/ caregiver as a source of information, an individual in a cultural context, a complex human being, and a partner in their care. Impacts to any and all of these roles may impact the quality of care.

CONCLUSIONS:Such a theory can promote opportunities for moving thefield forward and organizing the planning and interpretation of comparable studies. The articulation of such a theory may simulta-neously provide guidance for the QI researcher and an opportunity for refinement and improvement.Pediatrics2013;131:S110–S119

AUTHORS:Lawrence C. Kleinman, MD, MPH, FAAP,aand

Denise Dougherty, PhDb

aDepartment of Health Evidence and Policy, Mount Sinai School of

Medicine, New York, New York; andbChild Health and Quality

Improvement, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

KEY WORDS

quality of health care (measurement), research methods, applied research, quality improvement (research and practice), health services research, Donabedian, Deming

ABBREVIATION

QI—quality improvement

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2012-1427n

doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1427n

Accepted for publication Dec 20, 2012

Address correspondence to Lawrence C. Kleinman, MD, MPH, FAAP, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Department of Health Evidence and Policy, One Gustave Levy Place, Box 1077, New York, NY 10029. E-mail: lawrence.kleinman@mountsinai.org

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright © 2013 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

There exists an explicit imperative to improve the quality of health care de-livered to the American public. Two re-markable Institute of Medicine reports, To Err is Human and Crossing the Quality Chasm, codified the foundations for such work as they chronicled 2 decades of research characterizing pervasive deficits in quality.1,2

Sub-sequently, 9 years of reports ordered by the US Congress document large and persistent problems in quality, including disparities in quality by race, ethnicity, and income.3 The nation is coming to

agreement on a number of aims for health care, including health care for children. The overarching aims, asfirst articulated by Donald Berwick and col-leagues,4and now adopted by the

fed-eral government, are better care, better health, and lower cost. Better care is defined as health care that is safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable, and patient-centered.5In sum, the Institute of

Medicine and US Department of Health and Human Services reports articulate national goals. Recent legislation, in-cluding the Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act and the Affordable Care Act, signal a new day for the study and improvement of quality. There is much activity addressing quality within and around American health care in both the public and private sectors.6–14 For

children, this is most evident in the collaboration between the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to develop and guide 7 Centers of Excellence and 2 state Medicaid programs in the Pediatric Quality Measures Program.

A September 2012 Institute of Medicine report summarized aflurry of quality improvement (QI) activities and pointed to new directions aimed at making the US health care delivery system more of a“learning organization.”15The report

may be summarized as articulating the

perspective that, “Technology can fix what’s broken in health care.”16 This

optimism is consistent with urgent calls for action that fall short of em-pirical guidance or even a clear path to improvement. One potential path to bring action together with learning can be found in the form of applied social science.17As specifically applied to the

enhancement of performance, “ im-provement science” has been de-scribed as the systematic effort tofind

“out how to improve and make changes in the most effective way... examining the methods and factors that best work to facilitate quality improvement.”14 How to move QI forward is an ongoing subject of discussion.18–30

This article argues for the centrality of science, including rigorous theory de-velopment and testing, in moving the nation’s quality aims forward. In part, we build off of work we presented at the first 2 “Advancing the Science of Pediatric Quality Improvement Re-search” conferences in 2011 and 2012.31–33We identify gaps in the

cur-rent theory and practice of QI research and evaluation in health care and to suggest approaches to closing those gaps, focusing on pediatric QI as ap-propriate. We suggest specific designs should be matched to specific circum-stances for considering health care improvement and its evaluation. Fi-nally, we suggest how practical expe-rience can help to build a theory of applied QI in health care that can help researchers to identify generalizable

findings from QI evaluation and re-search, and help the nation achieve its goals.

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

A large stream of QI activities in health care are derived from the philosophy of total quality management and the work of Edwards Deming and Walter Shewhart.34The modern era of QI in health

care began with efforts to stimulate

providers’ use of clinical practice guidelines or to help providers meet

performance goals, benchmarked

against data from performance mea-sures.35–37This era began after it

be-came clear that merely producing clinical practice guidelines and pas-sively disseminating them was not leading to change. Although there are some compelling examples of suc-cessful QI efforts focused on specific clinical problems at the clinical micro-system level,15,38the current emphasis

in QI is on broader systemic efforts designed to change the environment in which providers practice. This empha-sis includes concepts such as systems reengineering,39delivery system

trans-formation, 6 s, LEAN, and systems change.23,26We consider QI broadly to

consist of those systematic data-based activities that focus on changing the production function of health care with an aim toward improving outcomes and/or efficiency. Although the fullness of QI may be manifest in iterative cycles of measurement and improvement, we agree with Berwick18,40 that the aims

are more important than the purity of the term; the empirical emergence of evidence and understanding creates opportunities to iteratively posit and test conceptual models and theories. His other point in 1996, that we need to broaden our ideas of what constitutes good science, is as relevant today as then.

In 2003, Galvin and McGlynn41

consid-ered 3 social science models, Change Theory, Tipping Point, and Diffusion Theory, to explore why QI had not resulted in a fundamentally improved health care system. They recom-mended a strategy that used perfor-mance measurement to drive change. Ten years later, observers are still asking why health care quality has largely not improved,34and attempting

A Science of QI: Theory for Practice We are not thefirst to suggest the im-portance of science and theory in QI.43–45

The journal Implementation Science, which publishes much of the research in QI, now recommends that manuscript submitters articulate their theory of change.46 Duncan Neuhauser, a

distin-guished expert in medicine and health care organization, recently summarized how theory development fits with the epistemology of knowledge and the scientific method, as well as the im-portance of theory in QI.47He reminds

us that“the scientific method consists of theory development, making pre-dictions (hypotheses), hypothesis test-ing, theory revision…” (p. 466), and notes that:“Theory is essential because it allows us to generalize to other places, times and circumstances…Theory is the way we learn from each other…” (p. 466). This approach is a clear de-scendant of Merton’s seminal vision of middle range theory.48

Among characteristics of good QI theory that Neuhauser and his colleagues suggest is the specification of variables and relationships among variables, use of outcome measures related to quality, numerical measurement of variables, and hypothesis testing (see Appendix). Although there may be disagreement about the defining characteristics of good theory in general, even those suggested by Neuhauser are almost never found in QI work, no less in QI research publications in the scientific literature.39,45,49–51 Thus, much of QI is

a“black box,”52providing little guidance

to those eager to take a more informed approach to improving care, and cast-ing doubt on its value as a science. Un-derstanding substantive interactions between specified aspects of inter-action and identifiable attributes of context may be critical to support in-telligent generalization from one QI project to the next, another reason to integrate theory into this work.53

The imperative to develop and test theory in QI may sound daunting to those who have not been trained in the social and behavioral sciences, where theory de-velopment and hypothesis testing are mundane. The word should not in-timidate: theory may be a well-specified conceptual model that predicts and explains what the intervention is, what need it is filling, what is supposed to happen as a result (the outcome), how and why the results happened on aver-age, and, optimally, reasons for varia-tions across sites in a multisite strategy. Evaluation scientists might label such a theory a logic model with a theory of change. Many theories are available to use as starting points in QI, or they can be combined in complementary ways. The important point is to carefully think through (and specify ahead of time) the relationships among variables, such as

“A leads to B, controlling for (or ac-counting for) C….”43,54,55

Research Methods for QI

Randomized controlled trials with the patient as the unit of intervention are often not optimal for health care QI studies. The unit of intervention is typ-ically the organization (eg, clinical practice, health plan, state), although it may be the individual provider. Cluster randomized controlled trials would be optimal, and have been conducted, primarily in other countries.56–60In the

United States, randomization of pro-viders, plans, and other QI locations is almost unheard of.61–63Rigorous

quasi-experiments or observational studies (eg, interrupted time-series, regres-sion discontinuity), preferably using comparison groups, have been rec-ommended,64 and will likely increase

as a result of recent efforts to train more researchers in their use. Even the use of contemporaneous nonequiv-alent control group designs would represent significant improvement over the dominant use of post-only

or pre-post studies without control groups.

The understanding of context on the results of QI interventions is essential to building this science and making it useful to frontline implementers. As social psychologists have demon-strated for more than 60 years, be-havior (and outcomes) is a function of the person (eg, the provider) in his or her environment. Although this premise is now accepted in the QI world, a true understanding of context, and an ability to test the impact of contextual varia-bles on improvement goals, is not likely to occur without development and more common use of standardized definitions and instruments. For ex-ample, the following are among the most common features hypothesized (mostly post hoc) to account for vari-ation in the results of performance improvement strategies: leadership, quality of team work, collective mind-fulness,65 resources, organizational

cultures, nature of hierarchies, and communications styles. These are often taken as an article of faith but the evi-dence base for them is highly variable, in part because they are either undefined or defined differently in every study. Health care experts have been skeptical about the value of using concepts and instruments from otherfields; nonethe-less, starting points outside of the health care context can fruitfully guide the de-velopment of health care–specific tools. Once the measures are defined, they can then be used to study the heterogeneity of effects in QI.66 Using a biological

identify gaps in resources or opportu-nities to improve processes that may be turned into targets for directed QI ini-tiatives. We must develop ways to deal productively in contexts replete with uncertainties.

Improving the science of improvement will take concerted effort and increased thoughtfulness in the clinical and health services research communities. Some entities have begun this process, including in the United States, the ademic Pediatric Association, the Ac-ademy for Healthcare Improvement, and the Improvement Science Research Network. In the United Kingdom, the new Health Foundation is taking major steps to build the science and contribute to achieving better care, better health, and lower costs. Others have suggested that a new international entity be formed to accelerate progress; reactions to this idea have been mixed, perhaps be-cause new organization may be seen to threaten rather than complement exist-ing ones.67

Still others are impatient with calls to improve and use improvement science, understandably focusing on an urgent call for action. However, action and theory are not incompatible: as it has been said, there is nothing so practical as a good theory.68Indeed, “action

re-search” is defined as “comparative research on the conditions and effects of various forms of social action and research leading to social action” us-ing iterative cycles of plannus-ing, action, and measurement.69 Action research

may be valuable in health care QI and other systems change research and offers significant promise as 1 foun-dation for intelligent change.70–73

Moving Forward: Toward a Model for Quality Improvement

We suggest a need to progress on 2 intersecting fronts: empirical work needs to document and improve care in real time; and stakeholder engagement

to develop a meaning-based under-standing of health care.

Structure, process, and outcome have been central to the theory of health care quality since Donabedian articulated an architecture for measuring health care quality and laid the foundation for the recent explosion of work in the

field. We call on the development of new theory to complement Dona-bedian’s work; to advance from his strict focus on measurement and to-ward health care operations and im-provement. By focusing on the tasks of health care in context, we may come to learn about what makes a difference in health and health care. An operations-based model supports QI activities as it elicits relationships between root causes and outcomes.

Such a model could then generate middle-range theories in the form of theories of change. These theories could be used to drive the design and implementation of interventions designed to improve quality. Such the-ories would be testable and support the modification of the overall theory.

One can easily imagine how the de-velopment of such theory could be leveraged to make the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycles of QI both more efficient (as it can drive the Plan and Do com-ponents) and more informative. Such a theory has the potential to simulta-neously limit degrees of freedom in QI activity and challenge those working in thefield to link their work in individual institutions to ideas that transcend such boundaries.74,75 This theory of

practice could suggest a taxonomy of the work of health care in relatively fundamental terms that describe con-structs that can both be measured and modified. Such a model could both support and rely on theories of change to advance an epistemology of QI ap-propriate to the health care context. An operations-based model of quality may challenge those of us struggling to

improve quality to refine and develop what is proposed here in a way that enhances our ability to understand and effect the production of quality health care. We set a toe in the water here.

Current Theory

According to Donabedian, the structure of care relates to the organization of health care delivery, whether at the level of the health care system, the or-ganizational or corporate unit, or the individual practice.70,71 An example of

a structural defect in health care is the lack of accessibility of care to those who are unable to afford it. On the mi-cro level, the inability of a patient to access a physician’s office that was not wheelchair accessible also would represent a structural impediment. Similarly, the organization of quality measurement, data infrastructure, and the nature of quality assessment or improvement activities are all struc-tural aspects of care. The process of care includes what is done and not done to or for the patient or by members of the health care system. Traditionally this was divided into 2 categories: terpersonal and technical. The in-terpersonal aspects of process related to how a patient was treated on a hu-man level: was the encounter with the health care system characterized by respect for the patient, his or her needs, desires, and privacy, and so forth. The technical aspects of health care can further be divided into medical decision-making and technical skill in imple-menting medical decisions. Brook and colleagues introduced the construct of appropriateness and necessity of care, based on the relative balance of risk, benefits, and importance.76–80The recent

field of patient safety has emerged to focus on the technical quality of care, specifically related to medical errors.23,81,82

notify or provide appropriate follow-up, as might occur after an abnormal cervical cancer screen is victimized by a medical error.

It is axiomatic that, in aggregate, health care impacts health, that its processes variably impact outcomes. Process is inherently more sensitive to measure change than are outcomes. Process measurement suffers in practice be-cause of uncertainty in the link between specific processes and specific out-comes. Uncertainty may reflect the actual relationship between process and outcomes, the measurement chal-lenge, or the research effort (eg, far more research links processes to out-comes in adults than in children).83

Outcomes of health care are defined as what actually becomes of the patient and may represent ultimate con-sequences: the degree of health or ill-ness or mortality or intermediate aspects of care such as the need for an emergency department visit. In general, the better the evidence linking the in-termediate outcome to the ultimate outcomes (or the more important the intermediate outcome is considered in and of itself), the more confident one can be using intermediate outcomes to describe the quality of care.

Because outcomes are the most visible and intuitive component of quality, there has been a large move toward emphasizing outcomes in policy deci-sions. When doing so, one must rec-ognize that because of the resiliency of individuals and populations, and be-cause of the indefinite relationship between processes and outcomes, outcomes are an insensitive way to measure changes in the quality of care. For example, only rarely does a child who is not fully immunized suffer from a vaccine-preventable illness, yet the failure to fully immunize each child represents a decrement in the quality of care. This problem is amplified when outcomes are uncommon.

Operations-based Model

The improvement of health care quality is a dynamic process and QI is just now being defined rigorously in the litera-ture.84 We propose that the work of

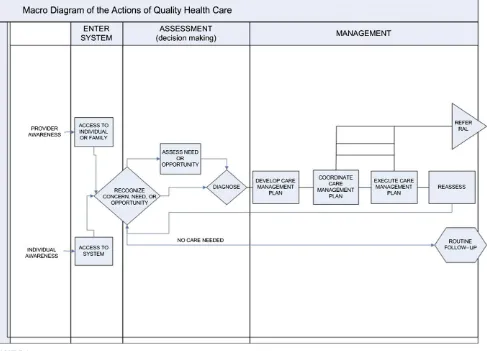

health care can be defined in an oper-ational and interpersonal framework to underlie QI research in much the same way that Donabedian defines quality research. Figure 1 illustrates that either through the action of an individual patient or the health care system, there emerges an awareness of a need or opportunity for health care. Subsequent to such awareness, access is or is not achieved. Once care is accessed, there comes an assess-ment of the extent to which there is a concern, a need, or an opportunity. Such conditions result, for example, from a symptom (CONCERN), a treat-able illness (NEED), or a circumstance (eg, underimmunized 15-month-old child representing an OPPORTUNITY). The concern, need, or opportunity then needs to be assessed and defined by the clinician or health care system (eg, the provision of visit reminders for preventive health care in a proactive managed care plan). A preliminary assessment is confirmed by history or physical and a diagnosis may be made (the “diagnosis” in this respect may represent a confirmation of the need to undertake further evaluation). A fur-ther care management plan may be negotiated and implemented, with co-ordination and execution of processes of care. We note that this care man-agement may be for further diagnostic work, treatment, follow-up, or some combination of those. At times, referral might represent an auxiliary or a new main path, reinitiating these con-structs. With new information comes the need to reassess; recognition of a concern, need, or opportunity, or potentially thefirm recognition of the identification of actionable information (even the recognition of uncertainty

that requires action) may restart the cycle. In this framework, diagnosis of a state occurs when the recognition becomes actionable. Actions may rep-resent large activities or smaller itera-tive data-gathering ones. The broadest constructs of the model are entry, as-sessment, and management, with the subordinate operations of access; rec-ognition, assessment, and diagnosis; and medical decision-making (developing a plan), coordination of care, execution of care, referral, and reassessment, respectively.

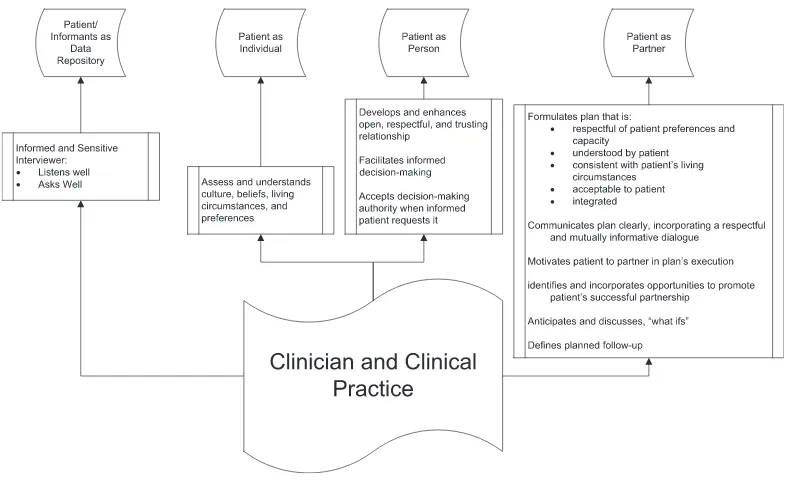

Figure 2 breaks down the various in-terpersonal components involved in providing health care. Interpersonal tasks include eliciting relevant clinical information from the patient or family, individualizing care plans with respect for patient values and recognizing life contexts (operationalized by many in the construct of shared decision-making), developing a relationship that optimizes the healing power of the therapeutic interpersonal relationship, and developing a partnership with the patient that reinforces other aspects of respectful behavior in a way that can be operationalized as a therapeutic partnership.

We articulate this model as a straw person to initiate specific discussion regarding how to reframe quality not only as an object for measurement, as was done so ably by Donabedian, but as a target for improvement. We present this theory too as an illustration of the potential to articulate paradigmatic theories that are overarching to the middle-range theories described in this article.

CONCLUSIONS

otherwise. These are systems beyond our control, but not beyond our di-rection. Understanding how to increase the desired outcome when raising a child requires some understanding of how children grow, what influences them, and where they are heading. It requires a theory that accounts for the dynamic nature of being a child in a family in a community and the mul-titude of potential influencers. Then a focus on those influences seen as key may help a parent to raise a healthy, well-adjusted, and productive young adult.

QI research in general and particularly that for children requires an apprecia-tion of the impact and changes over time, in terms of the structures, processes,

and outcomes of care in the immedi-ate future and across the life course. Evidence is a critical foundation for such work, but so are reasonable theories, articulated and specified for testing.

We suggest that the task of researchers working to build a thriving field of QI research includes the following:

Developing and extending the the-ory of health care operations and delivery through systematic in-quiry that incorporates both quan-titative and qualitative methods. An ideal theory will allow for the as-sessment of care both to an indi-vidual patient and to populations. The Institute of Medicine suggests 7 attributes of quality, includingequity, that should be accounted for at the population level.

Integrating theory and empiricalfindings to identify key variables that affect the quality of health care. We expect that some of these variables will be clinical process variables, others structural varia-bles (which may be as varied as systems for ongoing training, orga-nizational attributes, and access to technology), and operational pro-cess variables. As theory identifies a causal chain, some structural and process variables may emerge as sufficiently important to serve as outcomes in their own right or as proxies for clinical or other outcomes. Longer-term clinical

FIGURE 1

outcomes should be identified and may be monitored for trends across the body of change that is accom-plished.

Develop valid and reliable measures that permit the assessment of key variables in a variety of settings. Develop and assess tools andmethods that improve the ability of researchers and evaluators of QI work to grow the field. An im-proved understanding of the episte-mology of QI research and evaluation would be a critical component to both guide and assess their development.

Develop and evaluate policies that promote the conversion of infor-mation and understanding about health care QI from a private good to a public good.85,86 Althoughthere has been a good deal of at-tention paid to the“business case for quality,” much less attention

has been paid to how to develop sufficient value for private health care organizations that share rather than hoard information, data, and understanding. Public funds should support only QI work that is de-signed to provide information beyond understanding, whether a particular intervention worked in a particular organizational setting.

Develop and evaluate interventions that social science, organizational, or other theory suggest may hold promise to improve the quality of care. In developing an understand-ing of the impact of interventions, it will be important to assess attribu-tion as well as associaattribu-tion. Excellent design, triangulation through the use of complementary designs, and careful analysis, including the thoughtful incorporation of Bradford Hill’s classic principles may guide us in developing an understanding ofthe cause and effect of QI interven-tions. Attention to context may re-quire attention to closing gaps (additive models), changing pro-cesses (multiplicative models), or both.

We have articulated a theory of quality as a target for improvement that de-scribes clinical and interpersonal tasks that constitute our initial framing of the work of health care. These tasks occur within clinical, organizational, and community contexts that may require recognition of the“receptor sites”that define how those contexts will modify the meaning or measurement of these various operations in that context. Recognizing the active components of context on QI and how they interact with these operations will represent a fundamental task for the QI re-searcher. Nonetheless, by focusing on potentially observable operations of health care, this or similar frameworks

FIGURE 2

offer the potential to build on the Donabedian framework to support and

extend the conceptual model from the

more static construct of quality

mea-surement to the more dynamic

con-struct of QI research.

Quality and QI research require the collaboration of excellent listeners, so-phisticated methodologists, and con-ceptual and analytic thinkers, all coming together with open minds that are informed but not bound by theory. In this effort, the need to create a para-digm for that incorporates the benefit of multiple disciplines in pursuit of better health care can be achieved. When considering the quality of health care for children, additional complexities are added, as is the opportunity to in-corporate a fundamental appreciation

for the importance of the life course for children’s total health. In this effort, the need to create a paradigm for that incorporates the benefit of multiple disciplines in pursuit of better health care can be achieved.

APPENDIX

1. The variables and their relation-ships are clearly defined.

2. The resultant model or theory is generalizable to other organiza-tions.

3. The theory leads to predictions that can potentially be disproved.

4. The theory leads to the possibility of replication.

5. The theory simplifies reality. Sim-plicity is a virtue.

6. The theory predicts better than other theories.

7. Numerical measurement of varia-bles and their relationships are not required, but they are useful, owing to their preciseness.

8. The unit of analysis is defined. In [quality improvement], the unit of analysis is [often] the organization [or the provider]. In clinical re-search, the unit of analysis is often the patient. This has important re-search consequences.

9. The dependent outcome variable is related to quality, such as fewer errors, lower mortality, lower costs, and patient satisfaction. “This out-come variable is what makes it a theory of health care quality improve-ment.”[emphasis added].43(pp 466-467)

REFERENCES

1. Institute of Medicine. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999

2. Institute of Medicine.Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Qual-ity. Measuring health care qualQual-ity. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/qual/measurix.htm. Accessed December 1, 2012

4. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The

triple aim: care, health, and cost.Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759–769

5. Institute of Medicine.Crossing the Quality Chasm. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001

6. Agency for Healthcare Research and Qual-ity. CHIPRA children’s health care quality measurement and improvement activities. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/chipra. Accessed

December 1, 2012

7. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Medicaid CHIP program information. Qual-ity of Care. Available at: www.medicaid.gov/ Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/ Quality-of-Care/Quality-of-Care.html. Accessed December 1, 2012

8. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The national strategy for quality

improve-ment in health care. Available at: www.ahrq.

gov/workingforquality/. Accessed December

1, 2012

9. Khuri SF, Henderson WG, Daley J, et al; Principal Investigators of the Patient Safety in Surgery Study. Successful implementation of the Department of Veterans Affairs’National

Surgical Quality Improvement Program in the private sector: the Patient Safety in Surgery study.Ann Surg. 2008;248(2):329–336 10. New York State Department of Health.

Pa-tient safety center. Related public/private initiatives. Available at: www.health.ny. gov/professionals/patients/patient_safety.

Accessed December 1, 2012

11. WellPoint Inc. Press release. CMS adopts

private sector primary care solution to improve quality and reduce medical costs. Available at: http://ir.wellpoint.com/phoenix.

zhtml?c=130104&p=irol-newsArticle&ID= 1703173&highlight= (CMS adopts private sector solution to improve….) Accessed

September 5, 2012

12. Improvement Science Research Network. What is improvement science? Available at: http://isrn.net/about/improvement_science. asp. Accessed December 1, 2012

13. USAID Health Care Improvement Project.

The science of improvement. Available at; 2012www.hciproject.org/improvement_tools/ improvement_methods/science. Accessed

December 1

14. The Health Foundation. Evidence scan. Im-provement science. Available at: www.health. org.uk/publications/improvement-science/. Accessed December 2, 2012

15. Institute of Medicine. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2012

16. AHIP Solutions SmartBrief [ahip@smart-brief.com]. September 7, 2012

17. Freeman HE, Rossi PH. Furthering the ap-plied side of sociology.Am Sociol Rev. 1984; 49(4):571–580

18. Berwick DM. The question of improvement.

JAMA. 2012;307(19):2093–2094

19. McCannon J, Berwick DM. A new frontier in patient safety. JAMA. 2011;305(21):2221– 2222

20. Clancy CM, Berwick DM. The science of safety improvement: learning while doing.

Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(10):699–701 21. Pellegrin KL, Carek D, Edwards J. Use of

ex-perimental and quasi-exex-perimental methods for data-based decisions in QI. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1995;21(12):683–691

22. Chassin MR. Quality of care: how good is good enough?Isr J Health Policy Res. 2012; 1(1):4

24. Bielaszka-DuVernay C. Improving quality and safety. Available at: www.healthaffairs. org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php? brief_id=45. Accessed December 1, 2012

25. Croxson B, Hanney S, Buxton M. Routine monitoring of performance: what makes health research and development different?J Health Serv Res Policy. 2001;6(4):226–232 26. Chassin MR, Loeb JM. The ongoing quality

improvement journey: next stop, high re-liability. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4): 559–568

27. Leatherman ST, Hibbard JH, McGlynn EA. A research agenda to advance quality mea-surement and improvement. Med Care. 2003;41(suppl 1):I80–I86

28. McGlynn EA, Cassel CK, Leatherman ST, DeCristofaro A, Smits HL. Establishing na-tional goals for quality improvement.Med Care. 2003;41(suppl 1):I16–I29

29. Khodyakov D, Hempel S, Rubenstein L, et al. Conducting online expert panels: a feasibil-ity and experimental replicabilfeasibil-ity study.

BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:174 30. Rubenstein LV, Hempel S, Farmer MM, et al.

Finding order in heterogeneity: types of quality-improvement intervention pub-lications.Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(6): 403–408

31. Kleinman LC, Dougherty D. Health care quality improvement research: theory and its appli-cation in statistical analysis. Paper presented at: Pediatric QI Methods, Research, an Eval-uation Conference; April 29, 2011; Denver, CO. Available at: www.academicpeds.org/special-InterestGroups/QIfolder/Kleinman_Dougherty. pdf. Accessed December 2, 2012

32. Kleinman L. Welcome and overview pre-sentation. Paper presented at: 2nd Annual Advancing Quality Improvement Science for Children’s Healthcare Research Conference; April 27, 2012; Boston, MA. Available at: www. academicpeds.org/specialInterestGroups/ QIfolder/2012/Kleinman_BWelcome_Overview. pdf. Accessed December 1, 2012

33. Kleinman L. Risk adjustment for QI Re-search 101. Paper presented at: 2nd Annual Advancing Quality Improvement Science for Children’s Healthcare Research Conference; April 27, 2012; Boston, MA. Available at: www. academicpeds.org/specialInterestGroups/ QIfolder/2012/Kleinman_BWelcome_Overview. pdf. Accessed December 1, 2012

34. Deming WE.Out of the Crisis. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2000

35. Luce JM, Bindman AB, Lee PR. A brief his-tory of health care quality assessment and improvement in the United States.West J Med. 1994;160(3):263–268

36. Chassin MR, O’Kane ME. History of the quality improvement movement. In: Berns

SD, ed.Toward Improving the Outcome of Pregnancy III: Enhancing Perinatal Health Through Quality, Safety, and Performance Initiatives. March of Dimes Web site. De-cember 2010. Available at: www.march-ofdimes.com/TIOPIII_finalmanuscript.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2012

37. Nigam A. Changing health care quality paradigms: the rise of clinical guidelines and quality measures in American medi-cine.Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(11):1933–1937 38. McKethan A, Shepard M, Kocot SL, et al.

Improving quality and value in the US health care system. Bipartisan Policy Cen-ter. August 2009. Available at: http://bipar- tisanpolicy.org/library/report/improving-quality-and-value-us-health-care-system. Accessed December 1, 2012

39. Sanchez JA, Barach PR. High reliability organizations and surgical microsystems: re-engineering surgical care. Surg Clin North Am. 2012;92(1):1–14

40. Berwick DM. Harvesting knowledge from improvement.JAMA. 1996;275(11):877–878 41. Galvin RS, McGlynn EA. Using performance

measurement to drive improvement: a road map for change.Med Care. 2003;41(suppl 1): I48–I60

42. Kaplan HC, Provost LP, Froehle CM, Margolis PA. The Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ): building a theory of context in healthcare quality improvement.

BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(1):13–20

43. Hulscher ME, Schouten LM, Grol RP, Buchan H. Determinants of success of quality im-provement collaboratives: what does the literature show [published online ahead of print August 9, 2012]? BMJ Qual Saf.

44. Dixon-Woods M, Bosk CL, Aveling EL, Goeschel CA, Pronovost PJ. Explaining Michigan: de-veloping an ex post theory of a quality im-provement program. Milbank Q. 201;89(2): 167–205

45. Scott A, Sivey P, Ait Ouakrim D, et al. The effect offinancial incentives on the quality of health care provided by primary care physicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(9):CD008451

46. Eccles MP, Foy R, Sales A, Wensing M, Mittman B. Implementation Science six years on—our evolving scope and common reasons for rejection without review. Im-plement Sci. 2012;7:71

47. Best M, Neuhauser D. Did a cowboy rodeo champion create the best theory of quality improvement? Malcolm Baldrige and his award.BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(5):465–468 48. Merton RK. On sociological theories of the

middle range. In: Merton RK, ed.Social Theory and Social Structure. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, the Free Press; 1949:39–53

49. Shekelle PG, Pronovost PJ, Wachter RM, et al. Advancing the science of patient safety.

Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(10):693–696 50. Kaplan HC, Brady PW, Dritz MC, et al. The

influence of context on quality improve-ment success in health care: a systematic review of the literature.Milbank Q. 2010;88 (4):500–559

51. Øvretveit J. Understanding the conditions for improvement: research to discover which context influences affect improve-ment success.BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(suppl 1):i18–i23

52. Broer T, Nieboer AP, Bal RA. Opening the black box of quality improvement collabo-ratives: an Actor-Network theory approach.

BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:265 53. Kleinman LC, Eder M, Hacker K; for the

Context Subcommittee of the Outcomes Committee of the Community Engagement Key Function Committee of the National CTSA Consortium. White paper encouraging an agenda for social, behavioral, and eco-nomic sciences to advance measurement serving community based research. Sub-mitted to the National Science Foundation as part of its SBE 2020 planning activity. Available at: www.nsf.gov/sbe/sbe_2020/2020_pdfs/ Kleinman_Lawrence_224.pdf. Accessed De-cember 1, 2012

54. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Re-search and Practice. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008

55. DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC.

Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009

56. Huis A, Schoonhoven L, Grol R, Donders R, Hulscher M, van Achterberg T. Impact of a team and leaders-directed strategy to improve nurses’ adherence to hand hy-giene guidelines: a cluster randomised trial [published online ahead of print Au-gust 28, 2012].Int J Nurs Stud.

57. Drewelow E, Wollny A, Pentzek M, et al. Im-provement of primary health care of patients with poorly regulated diabetes mellitus type 2 using shared decision-making—the DE-BATE trial.BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13(1):88 58. Young D, Furler J, Vale M, et al. Patient

Engagement and Coaching for Health: The PEACH study—a cluster randomised con-trolled trial using the telephone to coach people with type 2 diabetes to engage with their GPs to improve diabetes care: a study protocol.BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:20 59. Berwanger O, Guimarães HP, Laranjeira LN,

coronary syndromes in Brazil: the BRIDGE-ACS randomized trial.JAMA. 2012;307(19): 2041–2049

60. Scales DC, Dainty K, Hales B, et al. A mul-tifaceted intervention for quality improve-ment in a network of intensive care units: a cluster randomized trial.JAMA. 2011;305 (4):363–372

61. Shafer MA, Tebb KP, Pantell RH, et al. Effect of a clinical practice improvement inter-vention on Chlamydial screening among adolescent girls.JAMA. 2002;288(22):2846– 2852

62. Holmboe ES, Hess BJ, Conforti LN, Lynn LA. Comparative trial of a web-based tool to improve the quality of care provided to older adults in residency clinics: modest success and a tough road ahead. Acad Med. 2012;87(5):627–634

63. Stout JW, Smith K, Zhou C, et al. Learning from a distance: effectiveness of online spirometry training in improving asthma care.Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(2):88–95 64. Mercer SL, DeVinney BJ, Fine LJ, Green LW,

Dougherty D. Study designs for effectiveness and translation research: identifying trade-offs.Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(2):139–154 65. Weick KE, Sutcliffe KM.Managing the

Un-expected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2007

66. Duan N. Description of ideal evaluation methods: quantitative approaches to con-text heterogeneity. In: Assessing the Evi-dence for Context-Sensitive Effectiveness and Safety of Patient Safety Practices: De-veloping Criteria. Contract Final Report. Agency for Healthcare Research and Qual-ity. December 2010. Available at: www.ahrq. gov/qual/contextsensitive/context12.htm. Accessed December 1, 2012

67. Wensing M, Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP. Does the world need a scientific society for re-search on how to improve healthcare?

Implement Sci. 2012;7:10. Available at: www. implementationscience.com/content/7/1/10. Accessed December 1, 2012

68. Lewin K.Field Theory in Social Science. New York, NY: Harper; 1952

69. Lewin K. Action research and minority problems.J Soc Issues. 1946;2(4):34–46 70. Burns D. Systemic Action Research: A

Strategy for Whole System Change. Bristol, UK: Policy Press; 2007

71. Kirschner K, Braspenning J, Jacobs JE, Grol R. Design choices made by target users for a pay-for-performance program in primary care: an action research approach. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:25

72. Green LW. Making research relevant: if it is an evidence-based practice, where’s the

practice-based evidence?Fam Pract. 2008; 25(suppl 1):i20–i24

73. Green LW, Glasgow RE. Evaluating the rele-vance, generalization, and applicability of research: issues in external validation and translation methodology.Eval Health Prof. 2006;29(1):126–153

74. Donabedian A. Definition of Quality and Approaches to Its Assessment (Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring, Vol 1). Chicago, IL: Health Administration Press; 1980

75. Donabedian A. The Criteria and Standards of Quality (Explorations in Quality As-sessment and Monitoring Series Vol. 2). Chicago, IL: Health Administration Press; 1982

76. Brook RH, Chassin MR, Fink A, Solomon DH, Kosecoff J, Park RE. A method for the de-tailed assessment of the appropriateness

of medical technologies. Int J Technol As-sess Health Care. 1986;2(1):53–63 77. Kahn KL, Kosecoff J, Chassin MR, et al.

Measuring the clinical appropriateness of the use of a procedure. Can we do it?Med Care. 1988;26(4):415–422

78. Park RE, Brook RH. Appropriateness stud-ies.N Engl J Med. 1994;330(6):432;–author reply 433–434

79. Kahan JP, Bernstein SJ, Leape LL, et al. Measuring the necessity of medical pro-cedures.Med Care. 1994;32(4):357–365 80. Brook RH. Assessing the appropriateness

of care—its time has come.JAMA. 2009;302 (9):997–998

81. Reason JT, Hobbs A. Managing Mainte-nance Error: A Practical Guide. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing Ltd; 2003

82. Reason JT.The Human Contribution: Unsafe Acts, Accidents, and Heroic Recoveries. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing Ltd; 2008

83. Kleinman LC. Prevention and primary care

research for children. The need for evi-dence to precede“evidence-based.” Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):345–351

84. O’Neill SM, Hempel S, Lim YW, et al. Identi-fying continuous quality improvement publications: what makes an improvement intervention ‘CQI’? BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20 (12):1011–1019

85. Kleinman LC, Kosecoff J, Dubois RW, Brook RH. The medical appropriateness of tym-panostomy tubes proposed for children under 16 years in the United States.JAMA. 1994;271:1250–1255

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2012-1427n

2013;131;S110

Pediatrics

Lawrence C. Kleinman and Denise Dougherty

Assessing Quality Improvement in Health Care: Theory for Practice

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/131/Supplement_1/S110

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

#BIBL

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/131/Supplement_1/S110

This article cites 50 articles, 7 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/quality_improvement_ Quality Improvement

e_management_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/administration:practic Administration/Practice Management

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2012-1427n

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/131/Supplement_1/S110

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.