The Health and Well-Being of Caregivers of Children With Cerebral Palsy

Parminder Raina, PhD*‡; Maureen O’Donnell, MD§; Peter Rosenbaum, MD㛳¶#; Jamie Brehaut, PhD**; Stephen D. Walter, PhD*; Dianne Russell, MSc*¶#; Marilyn Swinton, BSc¶; Bin Zhu, MSc*‡; and

Ellen Wood, MD‡‡

ABSTRACT. Objective. Most children enjoy healthy childhoods with little need for specialized health care services. However, some children experience difficulties in early childhood and require access to and utilization of considerable health care resources over time. Although impaired motor function is the hallmark of the cerebral palsy (CP) syndromes, many children with this develop-ment disorder also experience sensory, communicative, and intellectual impairments and may have complex lim-itations in self-care functions. Although caregiving is a normal part of being the parent of a young child, this role takes on an entirely different significance when a child experiences functional limitations and possible long-term dependence. One of the main challenges for parents is to manage their child’s chronic health problems effec-tively and juggle this role with the requirements of ev-eryday living. Consequently, the task of caring for a child with complex disabilities at home might be somewhat daunting for caregivers. The provision of such care may prove detrimental to both the physical health and the psychological well-being of parents of children with chronic disabilities. It is not fully understood why some caregivers cope well and others do not. The approach of estimating the “independent” or “direct” effects of the care recipient’s disability on the caregiver’s health is of limited value because (1) single-factor changes are rare outside the context of constrained experimental situa-tions; (2) assumptions of additive relationships and per-fect measurements rarely hold; and (3) such approaches do not provide a complete perspective, because they fail to examine indirect pathways that occur between predic-tor variables and health outcomes. A more detailed ana-lytical approach is needed to understand both direct and indirect effects simultaneously. The primary objective of the current study was to examine, within a single theory-based multidimensional model, the determinants of

physical and psychological health of adult caregivers of children with CP.

Methods. We developed a stress process model and applied structural equation modeling with data from a large cohort of caregivers of children with CP. This de-sign allowed the examination of the direct and indirect relationships between a child’s health, behavior and functional status, caregiver characteristics, social sup-ports, and family functioning and the outcomes of care-givers’ physical and psychological health. Families (nⴝ

468) of children with CP were recruited from 19 regional children’s rehabilitation centers that provide outpatient disability management and supports in Ontario, Canada. The current study drew on a population available to the investigators from a previous study, the Ontario Motor Growth study, which explored patterns of gross motor development in children with CP. Data on demographic variables and caregivers’ physical and psychological health were assessed using standardized, self-completed parent questionnaires as well as a face-to-face home in-terview. Structural equation modeling was used to test specific hypotheses outlined in our conceptual model. This analytic approach involved a 2-step process. In the first step, observed variables that were hypothesized to measure the underlying constructs were tested using con-firmatory factor analysis; this step led to the so-called measurement model. The second step tested hypotheses about relationships among the variables in the structural model. All of the hypothesized paths in the conceptual model were tested and included in the structural model. However, only paths that were significant were shown in the final results. The direct, indirect, and total effects of theoretical constructs on physical and psychological health were calculated using the structural model.

Results. The most important predictors of caregivers’ well-being were child behavior, caregiving demands, and family function. A higher level of behavior problems was associated with lower levels of both psychological ( ⴝ ⴚ.22) and physical health ( ⴝ ⴚ.18) of the caregivers, whereas fewer child behavior problems were associated with higher self-perception ( ⴝ ⴚ.37) and a greater ability to manage stress ( ⴝ ⴚ.18). Less caregiving de-mands were associated with better physical ( ⴝ.23) and psychological ( ⴝ.12) well-being of caregivers, respec-tively. Similarly, higher reported family functioning was associated with better psychological health ( ⴝ.33) and physical health ( ⴝ.33). Self-perception and stress man-agement were significant direct predictors of caregivers’ psychological health but did not directly influence their physical well-being. Caregivers’ higher self-esteem and sense of mastery over the caregiving situation predicted better psychological health ( ⴝ .23). The use of more stress management strategies was also associated with better psychological health of caregivers ( ⴝ.11). Gross income ( ⴝ.08) and social support ( ⴝ.06) had indirect overall effects only on psychological health outcome, From the *Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics,

‡McMas-ter University Evidence-Based Practice Centre, and㛳Department of Paedi-atrics, Faculty of Health Sciences, and #School of Rehabilitation Science, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; §Centre for Community Child Health Research, BC Research Institute for Children’s and Women’s Health, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Can-ada; ¶CanChild Centre for Childhood Disability Research, McMaster Uni-versity, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; **Clinical Epidemiology Unit, Ottawa Health Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; and ‡‡Department of Pediatrics, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

Accepted for publication Dec 16, 2004. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-1689

No conflict of interest declared.

Reprint requests to (P.R.) McMaster Evidence-Based Practice Centre, De-partment of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University, DTC, Room 306, 1280 Main St W, Hamilton, ON, Canada L8S 4L8. E-mail: praina@mcmaster.ca

whereas self-perception ( ⴝ.22), stress management ( ⴝ.09), gross income ( ⴝ.07), and social support ( ⴝ.06) had indirect total effects only on physical health out-comes.

Conclusions. The psychological and physical health of caregivers, who in this study were primarily mothers, was strongly influenced by child behavior and caregiv-ing demands. Child behavior problems were an impor-tant predictor of caregiver psychological well-being, both directly and indirectly, through their effect on self-per-ception and family function. Caregiving demands con-tributed directly to both the psychological and the phys-ical health of the caregivers. The practphys-ical day-to-day needs of the child created challenges for parents. The influence of social support provided by extended family, friends, and neighbors on health outcomes was second-ary to that of the immediate family working closely to-gether. Family function affected health directly and also mediated the effects of self-perception, social support, and stress management. In families of children with CP, strategies for optimizing caregiver physical and psycho-logical health include supports for behavioral manage-ment and daily functional activities as well as stress management and self-efficacy techniques. These data support clinical pathways that require biopsychosocial frameworks that are family centered, not simply techni-cal and short-term rehabilitation interventions that are focused primarily on the child. In terms of prevention, providing parents with cognitive and behavioral strate-gies to manage their child’s behaviors may have the potential to change caregiver health outcomes. This model also needs to be examined with caregivers of chil-dren with other disabilities.Pediatrics2005;115:e626–e636. URL: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2004-1689;

caregiver, well-being, disability, cerebral palsy, informal support, stress process model, structural equation model-ing.

ABBREVIATIONS. CP, cerebral palsy; GMFCS, Gross Motor Function Classification System; SES, socioeconomic status; OMG, Ontario Motor Growth; SEM, structural equation modeling; LLM, log linear modeling; RMSEA, root-mean-squared error of approx-imation; NNFI, Nonnormed Fit Index; CFI, Comparative Fit Index.

M

ost children enjoy healthy childhoods with little need for specialized services in the health care system. However⬃7.7% of chil-dren experience difficulties during their developing years and require access to and utilization of exten-sive health care resources over time.1Cerebral palsy(CP) is one such developmental disorder that begins in early childhood as a set of functional limitations that stem from disorders of the developing central nervous system.2The current estimated incidence of

CP is 2.0 to 2.5 per 1000 live births in developed countries.3Although impaired motor function is the

hallmark of the CP syndromes, many children also experience sensory, communicative, and intellectual impairments and may have complex limitations in self-care functions such as feeding, dressing, bathing, and mobility. These limitations can result in require-ments for long-term care that far exceed the usual needs of children as they develop.4,5We chose CP as

a prototype condition to study the issues that parents who care for a child with a disability face.

Family caregivers often shoulder the principal, multifaceted responsibilities of long-term disability

management.6Although caregiving is a normal part

of being the parent of a young child, this role takes on an entirely different significance when a child experiences functional limitations and possible long-term dependence. One of the main challenges for parents is to manage their child’s chronic health problems effectively while maintaining the require-ments of everyday living. In some cases, the provi-sion of such care can prove detrimental to both the physical health and the psychological well-being of parents of children with chronic disabilities and have an impact on family income, family functioning, and sibling adjustment.7

In the past 2 decades, tremendous changes in health care systems have exerted a shift toward out-patient community and home-based settings, which in turn have increased the responsibilities of infor-mal caregivers.8In addition, several factors that may

contribute to the perceived burden and stress expe-rienced by parents of children with disabilities exist. These factors include smaller family units, increased rate of marital breakdown,8technologic innovations,

and pharmacologic advancements in medicine.9

Consequently, the task of caring for a child with complex disabilities at home might be somewhat daunting for caregivers.

The notion of “caregiving as a career” connotes a dynamic process, whereby an individual moves through a series of stages that require adaptation and restructuring of responsibilities over time.4,10,11

These stages might include (1) anticipation for and acquisition of the caregiver role, (2) performance of tasks and responsibilities, and (3) eventual exit from the role.4,10,11Unlike a conventional career, however,

the caregiver role is usually not planned or chosen and is generally not seen as an appealing pursuit for the future.

It is not fully understood why some caregivers cope well and others do not. Stress has been con-ceived as the balance between external environmen-tal demands and the perceived internal ability to respond and may occur when the demands prevent the pursuit of other life objectives.4,8,9 Modifying

factors of caregiver stress include (1) the characteris-tics of the caregiver (eg, age, marital status, coping ability),12,13(2) characteristics of the recipient (eg, the

degree of disability),12,14 (3) the shared history

be-tween the caregiver and the person being cared for,4

(4) social factors (eg, access to social networks and social support),8,12(5) economic factors (eg

socioeco-nomic status [SES], ability to access formal care, em-ployment),4,12and (6) cultural context.4Each of these

factors may influence the outcome of the caregiving situation; together they suggest that stress occurs in a broader context than simply the provision of care for a child with a physical disability.

Several conceptual models describe the impact of stress on caregivers.9,15,16 These models have

single-factor changes are rare outside the context of constrained experimental situations; (2) assumptions of additive relationships and perfect measurements rarely hold; and (3) such approaches do not provide a complete perspective, because they fail to examine direct and indirect pathways that occur between pre-dictor variables and health outcomes. A more de-tailed analytical approach is needed to understand both direct and indirect effects simultaneously within a theory-based multidimensional model.

Our primary objective was to examine, within a single multidimensional model, a comprehensive set of factors that are relevant to the caregiving situation. The conceptual model (Fig 1) that guided this re-search is described in detail by Raina et al.17 The 5

constructs in the proposed model include (1) back-ground and context, (2) child characteristics, (3) care-giver strain, (4) intrapsychic factors, and (5) coping/ supportive factors. This research examines the direct and indirect associations between caregiver charac-teristics, sources of caregiver stressors, family func-tioning, and informal social support on the well-being of the caregivers of children with CP. Specifically, we hypothesized that an increase in a child’s disability as measured by the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS)18; the

Pedi-atric Evaluation of Disability Inventory, Part 119; and

the Health Utilities Index, selected questions,20 and

behavioral problems would be associated directly with poorer physical and psychological well-being of primary caregivers.7However, we also hypothesized

that the direct relationship between a child’s disabil-ity or his or her behavioral problems and parental well-being would be mediated by intrapsychic and coping/supportive factors as described in the pro-posed conceptual model (Fig 1).

METHODS Setting

CanChild studies are made possible through a partnership between the provincial government-funded CanChild Centre for Childhood Disability Research at McMaster University and the 19 publicly funded regional ambulatory children’s rehabilitation cen-ters in Ontario, Canada. These regional cencen-ters deliver a range of developmental therapies and services (predominantly physical, occupational, speech-language, and recreational therapies) pro-vided by developmental professionals who are trained and expe-rienced in both the assessment and the management of childhood disability. Each center serves the majority of eligible children in their area. The current study drew on a population that was available to the investigators from a previous study, the Ontario Motor Growth (OMG) study, which explored patterns of gross motor development in children with CP and where more details of the sampling process are described.21

Sample

Caregivers were recruited for the present study from a sam-pling frame, originally created in early 1996, of families who had participated in the OMG study. For the OMG study, children had been randomly selected in a stratified sampling procedure on the basis of age and level of motor function using the GMFCS18from 18 of 19 regional centers and 1 hospital-based therapy program in a community without a regional center. A total of 657 children and their families participated in the OMG study, 632 of whom were still involved at the end of OMG project; these 632 families were invited to participate in the current caregiver study.

Selection Criteria

One primary caregiver per household was selected for this study. The primary caregiver was defined as the person who is most responsible for the day-to-day decision making and care of the child; the family determined who was best considered the primary caregiver. Caregivers who were asked to participate in this study had to meet the following criteria: (1) have a child who had participated in the OMG study, (2) identify themselves as a primary caregiver whose child lived with them, (3) give written consent to participate, and (4) reside in Ontario. Initial recruitment involved mailing families a package that contained a letter, a consent form, and a brochure describing the study, along with a lottery ticket as an incentive to participate. Telephone follow-up with families was done by a person who was trained to answer any questions and obtain verbal consent.

Data Collection

The data were collected in 2 steps. First, for minimizing the time burden on the caregivers, a package that included an intro-ductory letter, a consent form, and a questionnaire was mailed to them for completion before a face-to-face interview. The self-report questionnaire collected demographic information about the caregiver, the child, and the family; the child’s ability to perform activities of daily living; the child’s day-to-day health; the child’s behavior; caregiver stress management strategies; caregiver per-ceptions of formal care for the child within the last 12 months; and the caregiver’s perception of his or her own general health and well-being (Table 1 summarizes the measures used).

The second step consisted of a home-based interview with the primary caregiver of the child with CP. Interviewers who were hired and trained specifically for this study conducted the inter-views. The structured, face-to-face interview collected information about caregiving assistance provided to the child, the caregiver’s perceptions of his or her own physical and mental health and emotional well-being, mastery and self-esteem, informal social support, family functioning, job-caregiving conflict issues, and gross income status (Table 2 briefly describes the measures used). The questionnaires were pretested with nonstudy families of

chil-dren with disabilities; the average length of each interview was⬃1 hour.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables in the data set. structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test specific hypotheses outlined in our conceptual model. This ana-lytic approach involves a 2-step process. In the first step, observed variables are hypothesized to measure the underlying constructs and tested using confirmatory factor analysis; this step leads to the so-called measurement model. The second step focuses on testing hypotheses about relationships among the variables in the struc-tural model. Several model diagnostic approaches were used to assess the integrity of each phase of the SEM development and the appropriateness of variables included in the model.7,22–24We used the PROC CALIS procedure in SAS version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), using covariance matrices and the maximum-likeli-hood estimation method to assess model fit. All of the hypothe-sized paths in the conceptual model (Fig 1) were tested and included in the structural model. However, only paths that were significant (P⬍.05) are shown in the final results.

The direct, indirect, and total effects of factors on health were calculated using the structural model. For example, the impact of stress management on psychological health involves 1 direct path (14) and 1 indirect path (13 ⫻16). The total effect (T) was estimated by summating the direct effect and the indirect effects [14⫹(13⫻16)⫽T].

The process of developing and testing a structural equation model is theory and data driven. Nonconvergence is not uncom-mon in the process of parameter estimation in such models. There-fore, a log linear modeling (LLM) analysis was conducted as an adjunct to the SEM analysis to assess the robustness of SEM analysis. LLM requires discrete measurements. Instead of latent continuous variables, categorized data were used in LLM analysis to specify the log linear model. The robustness of the SEM model was comparable to the LLM. However, SEM analyses identified more relationships than the LLM (which are not reported in this article).

RESULTS Description of the Sample

Of the initial sampling frame that contained 632 families, 42 caregivers were lost to follow-up. A total of 590 (93%) families were contacted, and 570 (90%) were eligible; 503 (88%) of the 570 consented. A final sample of 468 primary caregivers (82% of the 570 eligible families) provided data (Table 3). The results show that the age, gender, and marital status of our

TABLE 1. Child and Caregiver Questionnaire Measures

Variable Measure Description of Measure

Child

Motor severity GMFCS18 An ordinal descriptive scale of the gross motor

function abilities of children with CP Activities of daily living Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory:

Part 119

Child is rated as capable/unable on 73 self-care and 54 mobility items

Cognitive function Health Utilities Index: selected questions20 Items about child’s ability to learn, remember, think, and solve problems

Child behavior Survey Diagnostic Instrument48(SDI) SDI is a 24-item subset of the Child Behavior Checklist with 3 scales: conduct disorder, hyperactivity, and emotional disorder Caregiver

Caregiver health status Medical Outcomes Study: Short Form 36 Health Survey49(SF36)

The SF36 is a generic measure of health concepts related to functional status and well-being Perception of formal care Measures of Processes of Care50 Caregiver’s perceptions of the extent to which

specific behaviors of health professionals occur Stress management Coping Health Inventory for Parents11 Caregiver’s appraisal of their coping responses to management of family life when he or she has a child who is seriously/chronically ill SES of caregivers National Longitudinal Study of Children and

Youth20

caregiver sample was well matched to the corre-sponding OMG study. In addition, we compared our study sample with a national population sample in terms of age; gender distribution, with both samples being primarily female; and martial status. Our care-giver sample differed from the national population in the distribution of the educational categories. Both samples showed similar proportions at the lower and higher ends of the educational continuum (Fig 2).25

The mean age of the children was 10.6 (SD: 2.69) years, 56% of whom were boys. Half of the children with CP (49.8%) were first-born. The mean age of caregivers was 40.3 (SD: 6.72) years, and 94.4% were female, 89.7% of which were birth mothers. Lan-guage preference of caregivers was English (98.5%). The GMFCS levels indicated that of the children, 28% walked without restrictions (level I), 11% walked without assistive devices (level II), 19% walked with assistive mobility devices (level III), 21% had nonam-bulatory self-mobility with limitations (level IV), and 20% were severely limited even with the use of as-sistive technology (level V). The range, mean, and SD of the observed variables for caregivers are shown in Table 4. The correlations between latent constructs are shown in Table 5.

SEM

Measurement Model

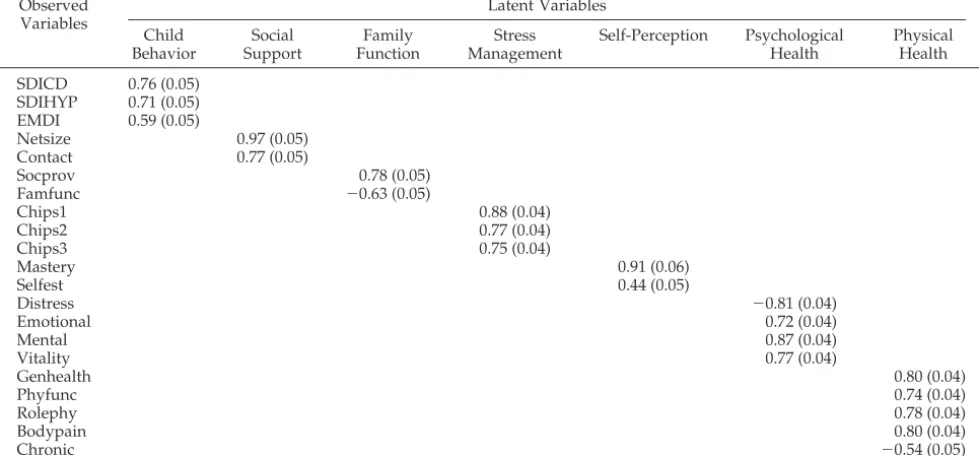

Initially, the hypothesized model was created with the predicted paths among the latent structural vari-ables predicted from the literature (see Fig 1). The confirmatory factor analysis was used to test the reliability of the hypothesized measurement model. Testing the fit of the measurement model led to

additional refinements to the conceptual model. First, we dropped 2 variables (“chronicity of dis-tress” and “reported health transitions” from SF-36) from the psychological health construct because of small factor loadings (⬍0.4) from the exploratory factor analyses with the psychological health factor. Second, the perception of formal care (Measures of Processes of Care) construct was dropped because of missing and nonapplicable responses to the ques-tionnaire. Finally, the disability construct was dropped because of its strong correlation with the caregiving demands construct. The caregiving de-mands construct was collapsed into a single ob-served variable because the measured variables “caregiver assistance-self care” and “caregiver assis-tance mobility” were highly correlated. Two vari-ables were relocated in the model: “vitality” from SF-36 was relocated to the psychological health con-struct from physical health concon-struct, and “social provision scale” was relocated to the family function construct instead of the social support construct.

After respecifying and reestimating the model, “income” was found to have more effect than “edu-cation,” and subsequently the latter variable was dropped from the SES construct. We also modified the model by dropping the “social functioning” vari-able from the social support construct to improve the goodness of fit. The final measurement model of 23 observed variables indicated an acceptable fit.

Several statistical tests and goodness-of-fit indices are used to assess the adequacy of model fit. In this study, the root-mean-squared error of approxima-tion (RMSEA), Bentler and Bonett’s Nonnormed Fit Index (NNFI), and Bentler’s Comparative Fit Index

TABLE 2. Caregiver Interview Measures

Variable Measure Description of Measure

Distress National Population Health Survey52 (NPHS)

Subset of items from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) related to distress (MH Q1A to Q1F) and chronicity of distress (MH Q1GQ1L)

Depression NPHS52 Subset of items from the CIDI related to major

depressive episodes (MHLTH Q2 to Q28)

Mastery NPHS53 Scale that measures caregiver control and

self-concept (MAST-Q1)

Self-esteem NPHS52 Six-item scale that measures caregiver self-esteem

(ESTEEM-Q1) Chronic health conditions National Longitudinal Study of

Children and Youth51(NLSCY)

Chronic health conditions that last 6 mo or more and are diagnosed by a health care professional (CHRON-Q1)

Health status McMaster Health Utility Index (HUI) in NPHS52

Items that measure health status, health-related quality of life, and producing utility scores (HSTATQ1 to HSTQ30)

Caregiving assistance Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI): Parts II and III19

Measures amount of caregiver assistance provided to a child during basic functional activities of daily living

Job-caregiving conflict Pearlin’s Scale54 Five-item scale related to job-caregiving conflicts Informal social support Social Network and Frequency of

Contact Index in NPHS52

Items summarize possible people in the caregiver’s social network and the average number of caregiver contacts in the past 12 mo with family, friends, and neighbors (SUP-Q7A to SUP-Q7H) Social Provision Scale (SPS) in

NLSCY51

Short version of the Social Provision Scale55that measures perceived social support from family and friends

Family functioning Family Assessment Device (FAD) in NLSCY51

(CFI) were used to assess model fit. Typically, an RMSEA value of⬍0.05 and an NNFI value and a CFI value close to 1 are indicative of good fit. However, it is not necessary for a model to display all of these characteristics to be considered acceptable.26 In this

study, the RMSEA value was 0.06, the NNFI value was 0.90, and the CFI value was 0.92. All factor loadings were substantial in magnitude, and signif-icantly different from 0, indicating that the latent constructs were adequately operationalized by the observed variables. The final standardized loadings of observed variables on the latent constructs are shown in Table 6.

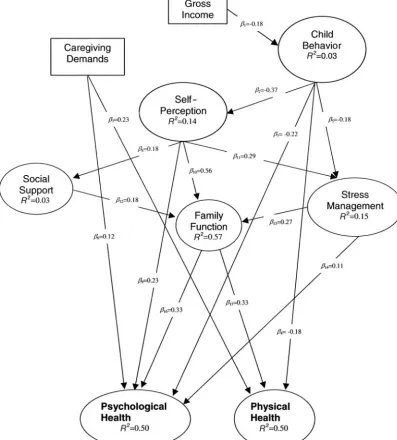

The Structural Model

A path diagram of the structural model of factors that influence the health of caregivers is shown in Fig 3. The latent constructs are denoted by ellipses. Two constructs are each represented by a single observed variable and are denoted by rectangles. Only paths that were significant (P ⬍ .05) are shown in the diagram.

The RMSEA was 0.06, NNFI was 0.90, and CFI was 0.91, which indicated an acceptable fit. The2for the

structural model was 583.3 with degrees of freedom 215 (P⬍ .0001). The standardized regression coeffi-cients and the correspondingR2statistics for each of

the significant hypothesized paths (P ⬍ .05) are shown in Fig 3. Five constructs influenced caregiv-ers’ psychological health, whereas 3 constructs influ-enced their physical health. Thus, for example, psy-chological health has an R2 of 0.50, indicating that

child behavior, self-perception, family function, care-giving demands, and stress management together accounted for 50% of the variation in psychological health.

Our conceptual model permits the estimation of both direct and indirect effects of constructs on care-giver health. With respect to specific hypothesized relationships in this analysis, the most important predictors of caregivers’ well-being were child be-havior, caregiving demands, and family function. An increase in reported child behavior problems was associated with decrease in both psychological (3⫽

⫺.22) and physical (4⫽ ⫺.18) health of the caregiv-ers, whereas fewer child behavior problems were associated higher self-perception (2⫽ ⫺.37) and a greater ability to manage stress (5⫽ ⫺.18; Fig 3).

Decreased caregiving demands were associated with an increase in physical (7⫽.23) and psychological

(6⫽.12) well-being of caregivers. Similarly, higher reported family functioning was associated with im-provements in both psychological health (16⫽ .33) and physical health (15⫽.33).

Fig 2. Caregiver sample selection and recruitment.

TABLE 3. Demography of Caregivers

Variable Caregiver

(n⫽468)

Gender,n(%)

Female 442 (94.4)

Male 26 (5.6)

Age, mean

Female 40.06⫾6.54

Male 44.42⫾8.32

Marital status,n(%)

Never married 25 (5.3)

Married or living with a partner 379 (81.0)

Separated 34 (7.3)

Divorced 19 (4.1)

Widowed 11 (2.4)

Caregiver relation with child with CP,n(%)

Mother 420 (89.7)

Father 25 (5.3)

Foster 15 (3.2)

Other as caregiver 8 (1.6)

Education level,n(%)

Elementary school 10 (2.1)

Secondary school 145 (31.0)

Trade, technical, or vocational school 79 (16.9)

Community college 125 (26.7)

University 28 (6.0)

Undergraduate degree 63 (13.5)

Postgraduate degree 18 (15.6)

Caregiver’s main activity,n(%)

Caring for family and working for pay/profit 272 (58.1)

Caring for family 173 (37.0)

Working for pay/profit 5 (1.1)

Going to school 6 (1.3)

Recovering from illness/on disability 3 (0.6)

Other 6 (1.3)

Hours usually worked,n(%)

Full-time (⬎30 h/wk) 208 (44.4)

Part-time (⬍30 h/wk) 100 (21.4)

Did not work for pay 160 (34.1)

Gross household income,n(%)

Less than $29 999 114 (24.3)

$30 000–$59 999 156 (33.3)

$60 000 or more 187 (40.0)

Self-perception and stress management were sig-nificant direct predictors of caregivers’ psychological health but did not directly influence their physical well-being. Caregivers’ higher self-esteem and sense of mastery over the caregiving situation predicted better psychological health (9 ⫽ .23). The use of more stress management strategies was also associ-ated with better psychological health of caregivers (14 ⫽ .11). In addition to direct relationships, we

observed the important mediating effect of family functioning on several latent constructs. For exam-ple, higher levels of self-perception (10⫽.56), social support (12 ⫽ .18), and stress management (13 ⫽

.27) all were associated with better family function-ing.

The total effect of hypothesized relationships be-tween the latent constructs on caregiver health out-come can also be calculated using the direct and indirect pathways in the conceptual model (Fig 3). Thus, the total effect of child behavior (T⫽ ⫺.38) on psychological health outcome was the sum of one direct pathway (3⫽ ⫺.22) and 7 indirect pathways (⫽ ⫺.16), whereas the total effect of child behavior on physical health wasT⫽ ⫺.28. Similarly, the total effect of stress management on psychological health

was T ⫽ .20. Gross income ( ⫽ .08) and social

support (⫽.06) had indirect overall effects on only psychological health outcome, whereas self-percep-tion ( ⫽ .22), stress management ( ⫽ .09), gross income ( ⫽ .07), and social support ( ⫽ .06) had indirect total effects only on physical health out-comes.

DISCUSSION

Several factors are known or thought to influence the health outcomes of parents who raise a child with a developmental disability. The direct and indirect relationships among these variables were examined using a single comprehensive structural equation model.

The psychological and physical health of caregiv-ers, who were primarily mothcaregiv-ers, was strongly influ-enced by child behavior and caregiving demands. These results reiterate associations made between caregiving and negative health outcomes in previous studies.24,27–30 Our study corroborated earlier

find-ings that child behavior problems are the single most important child characteristic that predicts caregiver psychological well-being.7 However, as with the

King et al study,7 the children’s behavioral issues

TABLE 4. Range, Mean, SD, and Sample Size for Observed Variables of Caregivers

Variables Range of Score High Score Equivalency Mean SD Sample Size

Distress score 0–24 More distress 4.71 4.35 468

Role: emotional 0–100 Better health 63.46 18.34 468

Mental health 0–100 Better health 69.34 42.60 468

Vitality 0–90 Better health 47.53 22.19 468

General health 0–100 Better health 67.90 23.04 468

Physical functioning 0–100 Better health 83.75 21.77 468

Role: physical functioning 0–100 Better health 68.75 39.02 468

Bodily pain 0–100 Better health 67.97 25.48 468

Chronic 0–9 Worse health 2.03 1.89 467

Netsize 2–8 More support 5.02 0.94 468

Contacts 6–45 More support 22.31 5.36 468

Social provision scale 0–18 More provision 14.51 3.40 468

Family functioning 0–36 More dysfunction 8.59 5.64 468

Integration 0–57 Better management 37.75 10.62 465

Support, esteem 0–54 Better management 30.63 10.28 464

Medical communication 0–24 Better management 13.66 5.78 462

Mastery 3–28 Superior mastery 14.88 5.63 468

Self-esteem 5–24 Greater self-esteem 19.25 3.24 468

Caregiving demand 0–100 Less demand 56.56 31.40 468

Conduct disorder 11–26 Worse behaviors 12.41 2.34 468

Hyperactivity 6–18 Worse behaviors 9.39 2.88 468

Emotional disorder 7–18 Worse behaviors 9.70 2.56 468

Gross household income 1–11 Better SES 8.25 2.49 457

Chronic indicates number of chronic conditions; netsize, existence of possible people to be contacted; contacts, number of contacts for all categories; integration, integration, cooperation, optimism; support, esteem, support, esteem, stability; medical communication, medical communication and consultation.

TABLE 5. Correlations Among Latent Constructs in the Measurement Model

Income Caregiving Demand

Child Behavior

Self-Perception Social Support

Family Function

Stress Management

Psychological Health

Caregiving demand 0.08

Child behavior ⫺0.17* 0.11*

Self-perception 0.11* 0.01 ⫺0.36*

Social support 0.02 0.09 0.05 0.18*

Family function 0.22* 0.11* ⫺0.30* 0.66* 0.32*

Stress management 0.13* 0.08 ⫺0.28* 0.35* 0.17* 0.50*

Psychological health 0.17* 0.15* ⫺0.42* 0.59* 0.18* 0.62* 0.43*

Physical health 0.14* 0.25* ⫺0.24* 0.32* 0.10 0.41* 0.22* 0.71*

were not assessed to be in the “clinical” ranges of severity. These nonclinical behavioral issues of a child with a disability also influenced caregivers’ psychological health indirectly through their effect on self-perception and family function. Thus, in planning interventions for the child and the family, it is important for service providers to consider chil-dren’s behavioral issues as an important determinant of the well-being of both the child and the caregiver. Clearly, it is important for health care providers to assess how caregivers are affected by behavioral as well as “functional” aspects of the child’s disability in the provision of comprehensive family-oriented services. In terms of prevention, providing parents with cognitive and behavioral strategies to manage their child’s behaviors may have the potential to change caregiver health outcomes.

Caregiving demands contributed directly to both the psychological and the physical health of the care-givers. Despite being a strong predictor of physical health of caregivers, there was no evidence to sup-port hypothesized relationships between caregiving demands and self-perception31or social support.32–34

This suggests that it is the practical day-to-day needs of the child that create challenges for parents but that neither their sense of self nor their social supports mediate the impact of their child’s level of disability on health outcomes.

The direct effect of self-perception and stress man-agement on psychological health supports the cen-tral relationships of the proposed model. Previous research has shown that social support, family func-tioning, and stress management may constrain re-sources with regard to caregiver health out-comes.7,12,29,35–41 The proposed direct link between

social support and health was not replicated in this study. Clearly, the influence of social support pro-vided by extended family, friends, and neighbors on health outcomes was secondary to that of the imme-diate family working closely together.

Family function played a central role in both the physical and the psychological health of caregivers. This construct affected health directly and also me-diated the effects of self-perception, social support, and stress management. These findings suggest that health care providers who work with families of children with long-term disabilities should develop interventions that support and nurture the family as a whole. Therefore, health care providers should be encouraged to value family functioning as much as the developmental and “technical” aspects of the services that are offered to children with complex disabilities.

The evidence in the literature supporting the link between SES and health is equivocal.30,42–44 It is

in-teresting that in this study, there was little evidence to support the proposed link between SES and care-giver health outcomes. Gross household income did not directly influence caregiver health. Instead, the direct effect of gross income suggests that higher income is predictive of improved child behavior. It is of course possible that there was insufficient socio-economic variation across the respondents for an SES effect to be detectable in this study.

The SEM method involves testing a theoretically derived model. Data-driven considerations may re-quire changes to the theoretical model that result in a model that does not match the original, intended model.45 In our SEM model, the final measurement

model was somewhat different from the

hypothe-TABLE 6. Measurement Model: Standardized Factor Loadings and SE of Observed Variables on Latent Variables

Observed Variables

Latent Variables

Child Behavior

Social Support

Family Function

Stress Management

Self-Perception Psychological Health

Physical Health

SDICD 0.76 (0.05) SDIHYP 0.71 (0.05) EMDI 0.59 (0.05)

Netsize 0.97 (0.05)

Contact 0.77 (0.05)

Socprov 0.78 (0.05)

Famfunc ⫺0.63 (0.05)

Chips1 0.88 (0.04)

Chips2 0.77 (0.04)

Chips3 0.75 (0.04)

Mastery 0.91 (0.06)

Selfest 0.44 (0.05)

Distress ⫺0.81 (0.04)

Emotional 0.72 (0.04)

Mental 0.87 (0.04)

Vitality 0.77 (0.04)

Genhealth 0.80 (0.04)

Phyfunc 0.74 (0.04)

Rolephy 0.78 (0.04)

Bodypain 0.80 (0.04)

Chronic ⫺0.54 (0.05)

sized model as a result of refinements to the concep-tual model. Additional refinements led to changes in the path model as well. Ultimately, the goal is to find a model that not only fits the data well from a sta-tistical perspective but also is one in which each parameter of the model has a substantively meaning-ful interpretation.

CONCLUSIONS

The development of interventions to reduce the stress experienced by caregivers of children with CP is both possible and necessary. The paths that emerged in the structural model provided evidence for the hypothesized relationships between variables that influence caregiver health outcomes. In our model, it seems that the family unit is the key regu-lating mechanism of health outcomes.36,46,47 Thus,

rather than target the child exclusively, interventions

and preventive strategies should also target caregiv-ers, who will in turn be able to respond to the unique characteristics of their child, eg, behaviors, tempera-ment, and functional limitations, in ways that should decrease the impact of their child’s disability on them.

The SEM analysis has made it possible to examine potentially important interrelated factors that con-tribute to caregivers’ health. In future research, it would be interesting to look at direct and indirect effects in this model across the trajectory of the care-givers’ role over time and to explore how changes in individual circumstances influence outcomes. These might include, for example, increase in the size and weight of a child with significant functional limita-tions associated with their developmental disabili-ties, at a time in their lives (particularly adolescence) when the physical capabilities of their caregivers

may begin to diminish with caregivers’ increasing age, or the loss of a person who has shared caregiv-ing responsibilities and moderated the impact of the child’s functional limitations. This method also al-lows for comparison of our model across varied pop-ulations, such as caregivers of children, youths, and the elderly. Additional exploration of the relation-ships among and between the factors that influence caring for children with other developmental disabil-ities is also warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr Raina holds a National Health Scholar Award from the National Health Research and Development Program and an In-vestigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Re-search. Dr Rosenbaum holds a Canada Research Chair in Child-hood Disability from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr Walter holds a Senior Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr Brehaut holds an Ontario Min-istry of Health and Long-Term Care Career Scientist Award.

CanChild Centre for Childhood Disability Research is a health system–linked research unit funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

We thank Susanne King for the input on the conceptual frame-work of the article, Dr Steven Hanna for the input on structural equation modeling, and the families who participated in our study. We also thank Helen Massfeller, Fulvia Baldassarre, and Roxanne Cheeseman for help in the preparation of this article.

REFERENCES

1. Canadian Institute of Child Health.The Health of Canada’s Children: A CICH Profile. 3rd ed. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Institute of Child Health; 2003

2. Bax M. Terminology and Classification of Cerebral Palsy.Dev Med Child Neurol.1964;6:297

3. Stanley FJ, Blair E, Alberman E.Cerebral Palsies: Epidemiology and Causal Pathways. London, England: Mac Keith Press; 2000

4. Blacher J. Sequential stages of parental adjustment to the birth of a child with handicaps: fact or artefact?Ment Retard.1984;22:55– 68

5. Breslau N, Staruch KS, Mortimer EA Jr. Psychological distress in moth-ers of disabled children.Am J Dis Child.1982;136:682– 686

6. Shillitoe R, Christie M. Psychological approaches to the management of chronic illness: the example of diabetes mellitus. In: Bennett P, Wein-man J, Spurgeon P, eds.Current Developments in Health Psychology. New York, NY: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1990:177–208

7. King G, King S, Rosenbaum P, Goffin R. Family-centered caregiving and well-being of parents of children with disabilities: linking process with outcome.J Pediatr Psychol.1999;24:41–53

8. Dumas D, Peron J, Peron Y.Marriage and Conjugal Life in Canada (Report No. 91–534E). Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Statistics Canada; 1992 9. Eicher PS, Batshaw ML. Cerebral palsy.Pediatr Clin North Am.1993;40:

537–551

10. Aneshensel CS, Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Zarit SH, Whitlatch CJ.Profiles in Caregiving; The Unexpected Career. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1995 11. McCubbin H, Patterson J. The Family Stress Process: The Double ABCX Model of Adjustment and Adaptation.Marriage Fam Rev.1983;6:7–35 12. Sloper P, Turner S. Risk and resistance factors in the adaptation of

parents of children with severe physical disability.J Child Psychol Psy-chiatry.1993;34:167–188

13. Wallander JL, Varni JW, Babani L, DeHaan CB, Wilcox KT, Banis HT. The social environment and the adaptation of mothers of physically handicapped children.J Pediatr Psychol.1989;14:371–387

14. Cadman D, Rosenbaum P, Boyle M, Offord DR. Children with chronic illness: family and parent demographic characteristics and psychosocial adjustment.Pediatrics.1991;87:884 – 889

15. McKinney B, Peterson RA. Predictors of stress in parents of develop-mentally disabled children.J Pediatr Psychol.1987;12:133–150 16. Dyson LL. Response to the presence of a child with disabilities: parental

stress and family functioning over time.Am J Ment Retard.1993;98: 207–218

17. Raina P, O’Donnell M, Schwellnus H, et al. Caregiving process and

caregiver burden: conceptual models to guide research and practice.

BMC Pediatr.2004;4:1.

18. Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, Russell D, Wood E, Galuppi B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol.

1997;39:214 –223

19. Haley SM, Coster WJ, Ludlow LH. Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI). Boston, MA: Trustees of Boston University; 1992 20. Feeny D, Furlong W, Boyle M, Torrance GW. Multi-attribute health

status classification systems. Health Utilities Index.Pharmacoeconomics.

1995;7:490 –502

21. Rosenbaum PL, Walter SD, Hanna SE, et al. Prognosis for gross motor function in cerebral palsy: creation of motor development curves.

JAMA.2002;288:1357–1363

22. Mittelman MS, Ferris SH, Shulman E, et al. Comprehensive support program: effect on depression in spouse-caregivers of AD patients.

Gerontologist.1995;35:792– 802

23. Beckman PJ. Influence of selected child characteristics on stress in families of handicapped infants.Am J Ment Defic.1983;88:150 –156 24. Friedrich WN, Wilturner LT, Cohen DS. Coping resources and

parent-ing mentally retarded children.Am J Ment Defic.1985;90:130 –139 25. Brehaut JC, Kohen DE, Raina P, et al. The health of primary caregivers

of children with cerebral palsy: how does it compare with that of other Canadian caregivers? Pediatrics. 2004;114(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/114/2/e182

26. James LR, Mulaik SA, Brett JM.Causal Analysis: Assumptions, Models, and Data. 1st ed. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1982

27. Gowen JW, Johnson-Martin N, Goldman BD, Appelbaum M. Feelings of depression and parenting competence of mothers of handicapped and nonhandicapped infants: a longitudinal study.Am J Ment Retard.1989; 94:259 –271

28. Kazak AE, Marvin RS. Differences, difficulties and adaptation: stress and social networks in families with a handicapped child.Fam Relat.

1984;33:67–76

29. Dunst CJ, Trivette CM, Cross AH. Mediating influences of social support: personal, family, and child outcomes.Am J Ment Defic.1986; 90:403– 417

30. Kitagawa EM, Hauser PM.Differential Mortality in the United States: A Study in Socioeconomic Epidemiology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univer-sity Press; 1973

31. Skaff MM, Pearlin LI, Mullan JT. Transitions in the caregiving career: effects on sense of mastery.Psychol Aging.1996;11:247–257

32. Palfrey JS, Walker DK, Butler JA, Singer JD. Patterns of response in families of chronically disabled children: an assessment in five metro-politan school districts.Am J Orthopsychiatry.1989;59:94 –104 33. Musil CM. Health, stress, coping, and social support in grandmother

caregivers.Health Care Women Int.1998;19:441– 455

34. MaloneBeach EE, Zarit SH. Dimensions of social support and social conflict as predictors of caregiver depression.Int Psychogeriatr.1995;7: 25–38

35. Frey KS, Greenberg MT, Fewell RR. Stress and coping among parents of handicapped children: a multidimensional approach.Am J Ment Retard.

1989;94:240 –249

36. Lambrenos K, Weindling AM, Calam R, Cox AD. The effect of a child’s disability on mother’s mental health.Arch Dis Child.1996;74:115–120 37. Krause N. Perceived health problems, formal/informal support, and

life satisfaction among older adults.J Gerontol.1990;45:S193–S205 38. Kronenberger WG, Thompson RJ Jr. Psychological adaptation of

moth-ers of children with spina bifida: association with dimensions of social relationships.J Pediatr Psychol.1992;17:1–14

39. Ransom DC, Fisher L, Terry HE. The California Family Health Project: II. Family world view and adult health.Fam Proc.1992;31:251–267 40. Barakat LP, Linney JA. Children with physical handicaps and their

mothers: the interrelation of social support, maternal adjustment, and child adjustment.J Pediatr Psychol.1992;17:725–739

41. Scharlach AE, Boyd SL. Caregiving and employment: results of an employee survey.Gerontologist.1989;29:382–387

42. Haan MN, Kaplan GA, Syme SL. Socioeconomic status and health: old observations and new thoughts. In: Bunker JP, Gomby DS, Kehrer BH, eds.Pathways to Health: The Role of Social Factors. Menlo Park, CA: Henry Kaiser Family Foundation; 1989:76 –135

43. Freeman HE. Social factors in the chronic disease. In: Levine S, Reeder LG, Freeman HE, eds.Handbook of Medical Sociology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1972:63–107

Study of One Million Persons by Demographic, Social and Economic Factors(Report No. 88 –2896). Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1981

45. Hayduk LA.Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1987

46. Friedrich WN. Predictors of the coping behavior of mothers of handi-capped children.J Consult Clin Psychol.1979;47:1140 –1141

47. Erickson M, Upshur CC. Caretaking burden and social support: com-parison of mothers of infants with and without disabilities.Am J Ment Retard.1989;94:250 –258

48. Boyle MH, Offord DR, Hofmann HG, et al. Ontario Child Health Study. I.Methodology. Arch Gen Psychiatry.1987;44:826 – 831

49. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Sur-vey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection.Med Care.

1992;30:473– 483

50. King GA, King SM, Rosenbaum PL. How mothers and fathers view professional caregiving for children with disabilities.Dev Med Child Neurol.1996;38:397– 407

51. Statistics Canada. NLSCY Data Dictionary Cycle 2, Release 3. Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada; 2003

52. Statistics Canada. NPHS 1996/97 Household Component Questionnaire. Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada; 1998

53. Statistics Canada. NPHS 1994-95 Household Component Questionnaire. Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada; 1996

54. Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures.Gerontologist.

1990;30:583–594

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2004-1689

2005;115;e626

Pediatrics

Walter, Dianne Russell, Marilyn Swinton, Bin Zhu and Ellen Wood

Parminder Raina, Maureen O'Donnell, Peter Rosenbaum, Jamie Brehaut, Stephen D.

The Health and Well-Being of Caregivers of Children With Cerebral Palsy

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/115/6/e626

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/115/6/e626#BIBL

This article cites 38 articles, 2 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

y_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/psychiatry_psycholog

Psychiatry/Psychology

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/neurology_sub

Neurology

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/disabilities_sub

Children With Special Health Care Needs

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2004-1689

2005;115;e626

Pediatrics

Walter, Dianne Russell, Marilyn Swinton, Bin Zhu and Ellen Wood

Parminder Raina, Maureen O'Donnell, Peter Rosenbaum, Jamie Brehaut, Stephen D.

The Health and Well-Being of Caregivers of Children With Cerebral Palsy

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/115/6/e626

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.