YOUTH INTEGRITY IN

VIETNAM

PILOTING TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL’S

YOUTH INTEGRITY SURVEY

Transparency International (TI) is the global civil society organisation leading the fight against corruption. Through more

than 90 chapters worldwide and an international secretariat in Berlin, Germany, TI raises awareness of the damaging

effects of corruption and works with partners in government, business and civil society to develop and implement

effective measures to tackle it.

www.transparency.org

Towards Transparency (TT) is a registered Vietnamese non-profit and non-state consultancy organisation that was

established in 2008 to contribute to national efforts in promoting transparency and accountability for corruption

prevention and fighting. In March 2009, TT became the National Contact of Transparency International (TI) in Vietnam.

In this capacity, TT supports and coordinates emerging activities of TI in Vietnam, within the framework of the TI Vietnam

Program “Strengthening Anti-corruption Demand from Government, Private Sector and Society, 2009-2012.”

www.towardstransparency.vn

Center for Community Support Development Studies (CECODES) is a non-profit, non-governmental research centre

which undertakes research on policy impact assessment and implement solutions on capacity strengthening for

communities, especially disadvantaged communities. The organisation contributes to the improvement of policies and

governance capacity towards balancing the three institutions: State, Market and Civil Society. Through a number of

high-profile projects, CECODES has become a leading institution in Vietnam working in promoting civil society, strengthening

its voice and its engagement with the state. Transparency and good governance is another pillar of CECODES’s work.

Cooperating with key national and well-known international partners, the organisation delivers action-based research

results which are relevant for policy making and policy dialogues.

www.cecodes.org

Développement, Institutions et Mondialisation

(DIAL) is a leading research centre in development economics in France,

which brings together researchers from the Université Paris-Dauphine and from the French Research Institute for

Development. DIAL provides internationally recognized scientific production, advanced academic training in several

countries, and support in the implementation of surveys in developing countries through its partnerships and foreign

branches in Senegal and in Vietnam. Its activities include developing methodological tools, promoting research and

reflection on public policy with original data of high quality through surveys, enhancing capacities and democratic debate

in the South.

www.dial.prd.fr

Centre of Live and Learn for Environment and Community (Live&Learn) is a Vietnamese non-profit organisation

established by the Vietnam Union of Science and Technology Associations. Live&Learn’s mission is to foster greater

understanding and action towards a sustainable future through education, community mobilisation and supportive

partnerships. Building learning tools and good governance processes have been adopted to address these issues.

Live&Learn is currently implementing and facilitating a number of projects on good governance and sustainable

development with youths in its network throughout Vietnam, enabling information to be shared on related topics.

www.livelearn.org

This report was made possible by the financial support of the TI Vietnam Programme, which is funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID), the Embassy of Finland, IrishAid and the Embassy of Sweden.

The report is the result of collective work between Towards Transparency and Transparency International, which initiated, supported and coordinated the survey, the Center for Community Support Development Studies (CECODES) which in particular lead the analysis and writing of the report, Développement, Institutions et Mondialisation (DIAL) which especially lead the development of the methodology of the research, and Live and Learn which conducted the fieldwork

Authors: Dang Giang (Center for Community Support Development Studies), Nguyen Thi Kieu Vien (Towards Transparency), Nguyen Thuy Hang (Live&Learn), Mireille Razafindrakoto (Développement, Institutions et Mondialisation), Francois Roubaud (Développement, Institutions et Mondialisation), and Matthieu Salomon (Towards Transparency)

Editors: Stephanie Chow (Towards Transparency), Samantha Grant (Transparency International) and Matthieu Salomon (Towards Transparency)

Design: Stephanie Chow (Towards Transparency)

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank all the individuals who contributed to all stages of the research and the preparation of the report. Our gratitude goes to many colleagues who have invested time and effort, particularly Pham Minh Tri (Center for Community Support Development Studies), Dang Dinh (Center for Community Support Development Studies) and Do Van Nguyet (Live&Learn) for their valuable contributions. In addition, we would like to thank the Vietnam Fatherland Front for their support in the fieldwork, the Youth Research Institute for their fruitful inputs in the design of the methodology and all the young people from Live&Learn who interviewed over 1,500 people across 11 provinces in Vietnam to make up the Youth Integrity Survey.

Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. All information was believed to be correct as of June 2011. Nevertheless, the authors cannot accept responsibility for the consequences of its use for other purposes or in other contexts. Cover Photo: ©flickr/k_t

ISBN: 978-3-935711-80-7

CONTENTS

FOREWORD 7

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

8

1. INTRODUCTION

12

Why the Vietnam Youth Integrity Survey (YIS) pilot?

12

The Process of Developing the New Methodology: A collaborative approach

13

2. THE METHODOLOGY

14

The Concept

14

The Sampling Design

14

The Questionnaire Design

15

The Field Work

15

3. KEY FINDINGS

16

3.1 Youth Values and Attitudes towards Integrity

16

3.2. Youth Experiences and Behaviours

28

3.3. The Environment: influences on youth

37

4. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

42

4.1 Key Conclusions

42

4.2 Recommendations

43

ENDNOTES 46

ANNEX 1: KEY PARAMETERS OF THE SAMPLE

48

ANNEX 2: THE METHODOLOGY IN DETAIL

50

The Sampling Design, Extrapolation and Precision of the Estimators

50

The Questionnaire Design

52

The Field Work

53

ANNEX 3: THE QUESTIONNAIRE

54

BIBLIOGRAPHY 68

FIGURES

FIGURE 1 Experiences of corruption among those who have contact during the past 12 months:

youth versus adults 9 FIGURE 2Willingness to take decisions which violate integrity in different situations:

youth versus adults 10 FIGURE 3 Values on wealth, success and integrity (wealth versus honesty):

youth versus adults 16 FIGURE 4 Values on wealth, success and integrity (income versus honesty):

youth versus adults 17 FIGURE 5A Values on wealth and success and integrity: youth versus adults 18 FIGURE 5B Youth values on wealth, success and integrity: broken down by living standards and education levels 19 FIGURE 6 Attitude to integrity- average perception of corrupt behaviours:

youth versus adults 20 FIGURE 7 Averaged youth acceptance of corrupt behaviours:

broken down by education levels 22

FIGURE 8 Youth perception on giving extra payment to receive better medical treatment 23 FIGURE 9A Lack of integrity as a serious problem:

youth versus adults 24 FIGURE 9B Lack of integrity as a serious problem:

broken down by education levels 25 FIGURE 10A Agreement with a “relaxed” definition of integrity:

youth versus adults 26 FIGURE 10B Agreement with a “relaxed” definition of integrity:

broken down by education levels 27 FIGURE 11A Experiences of corruption among those who have contact in the past twelve months:

youth versus adults 28

FIGURE 11B Experiences of corruption among those who have contact in the past twelve months:

broken down to geographic areas 30 FIGURE 12 A Youth rating of integrity of public services as “very good” and “very bad”:

best educated 31 FIGURE 12B Youth rating of integrity of public services as “very good” and “very bad”:

youth in general 31 FIGURE 13 Willingness to take decisions which violate integrity in different situations:

youth versus adults 32 FIGURE 14 Commitment to report corruption:

youth versus adults 33 FIGURE 15A Reasons for not reporting corruption:

youth versus adults 34 FIGURE 15B Reasons for not reporting corruption:

broken down by youth living standards 35

FIGURE 15C Reasons for not reporting corruption:

broken down by youth educational levels 35 FIGURE 16 Agreement that youth can play a role in promoting integrity:

broken down by education levels 36 FIGURE 17A Information sources shaping youth values on

integrity 37

FIGURE 17B Information sources shaping youth values on integrity:

broken down by education levels 38

FIGURE 18 Role models for youth in regard to integrity: youth in general 39 FIGURE 19 Knowledge of rules and regulations on integrity promotion and anti-corruption:

youth in general 40 FIGURE 20 Youth commitment to report corruption:

broken down by anti-corruption knowledge and education 41

FOREWORD

For more than 18 years, Transparency International has been working to stop corruption and promote transparency, accountability and integrity at all levels and across all sectors of society. We approach our third decade with the firm belief that for change to be sustainable, it has to be underpinned by widespread public support and engagement. It is ultimately people who bring lasting change by demanding accountability from those who are in positions of entrusted power. The openness, courage and energy of young people, mean their engagement in the fight against corruption is critical to driving positive change.

One-third of the world’s population consists of young people who are, as this report shows, more often victims of corruption than adults. Transparency International recognises the potential young people have to transform today’s reality and make a lasting impact as tomorrow’s political and business leaders.

Like corruption, integrity is a learned behaviour, so securing a commitment to integrity by both current and future generations requires the core values of transparency and integrity be championed by society and nurtured from an early age.

Having a better understanding of young people’s views and experiences provides a basis for more effective anti-corruption efforts and allows us to equip them with the information, skills and support they need to face and resist the corruption they deal with on a daily basis.

The following report exemplifies this holistic approach by examining the views and experiences of youth, as well as looking at the wider environment that influences their choices and behaviour. The methodology developed through this project is an important contribution towards developing tools to better understand young people’s experiences of corruption and informing targeted and results oriented programmes.

As we seek to take our anti-corruption work to scale, we will carry out this research in a growing number of countries over the next five years – reaching out and engaging greater numbers of young people in the anti-corruption movement. Pascal Fabie

Group Director

Chapters’ Network and Programmes

Transparency International

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1. INTRODUCTION

With over 55% of the population of Vietnam under 30 years old and international experience showing that young people are particularly vulnerable to corruption, it is imperative that youth are targeted in anti-corruption activities. Initiatives such as Project 137, signed by the Prime Minister in December 2009, to introduce anti-corruption curricula in school and universities in Vietnam, provides an opportunity to influence the values of young people and empower them to make concrete changes. Yet, to ensure that such initiatives are effective, there needs to be greater understanding of the beliefs, behaviours and experiences which make up the integrity of Vietnamese youth.

The Youth Integrity Survey (YIS), which interviews 1,022 youth on their attitudes to integrity and corruption, is intended to improve such understanding, thus helping to establish more targeted and effective anti-corruption initiatives.

2. METHODOLOLGY

Building on the experience of Transparency International (TI) in this area (especially research initiated by TI Korea), Towards Transparency (TT) has led the review of the original YIS and piloted the new methodology in Vietnam with the support of researchers from DIAL, the Center for Community Support Development Studies (CECODES) and the wider TI movement.

Using TI’s definition of integrity as “[b]ehaviours and actions, consistent with a set of moral and ethical principles and standards, embraced by individuals as well as institutions, that create a barrier to corruption” as the basis, the YIS pays special attention to corruption issues, covering youth values and attitudes towards integrity, their experiences with corruption, and their actions when faced with corruption. The research sample covered a random sample of young people between 15-30 years old to allow conformity with both the Vietnamese classification of youth (16-30 years), and the international definition of 15-24 years. To explore potential

differences between youth attitudes, behaviours and values from the rest of the population, the research also sampled a control group of 519 “adults” over 30 years old. Face to face interviews were carried out between August and December 2010 by Live&Learn, with the facilitation of CECODES and collaboration with provincial departments of the Vietnam Fatherland Front. Young volunteers, students and recent graduates, were recruited and trained to conduct the interviews across 11 urban and rural provinces across Vietnam.

3. KEY FINDINGS

3.1 VALUES AND ATTITUDES TOWARDS

INTEGRITY

To better understand their conceptual understanding of integrity and corruption, the YIS investigates youth values and attitudes towards integrity, such as what they consider to be right or wrong, which acts they perceive as corrupt, how they understand the concept of integrity and how integrity is positioned in their value system.

Responses demonstrate that the majority of youth place a strong importance on integrity at the conceptual level. 95% of youth partly or totally agree that being honest is more important than being rich and 91% agree that being honest is more important than increasing income.

When faced with specific examples of corrupt behaviours, an average of 88% of youth considered the behaviours to be wrong, close to the adult average of 91% of respondents. However, findings also clearly show that youth relax their values according to specific situations. For example when faced with the situation of “giving additional payments or gifts in a hospital in order to get better treatment”: 32% of youth consider it not to be wrong, with an additional 13% of youth acknowledging that it is wrong, but still acceptable. Moreover youth are becoming more willing to compromise their integrity as they grow older.

Whilst 83% to 86% of youth surveyed perceived a lack of integrity (including corruption) to be very harmful for their generation, the economy and the development of the country, only 78% considered it to have a direct impact on their family and friends. This perhaps indicates that their understanding of corruption continues to operate on a somewhat abstract level, and while youth can perceive the negative impacts on the country at large, they are less able to perceive its effects on their direct social environment and daily lives.

Despite these strongly shared values and principles, around one third of youth (35%) are also ready to relax their definition of integrity when it is financially advantageous, will help in solving a problem or if the amount of bribe changing hands is small. This percentage is even higher amongst the least educated youth, where for example, half of the youth who finished only up to the end of primary school found it acceptable to engage in petty corruption, compared to 27% of youth who had received post-secondary education.

3.2 EXPERIENCES AND BEHAVIOURS

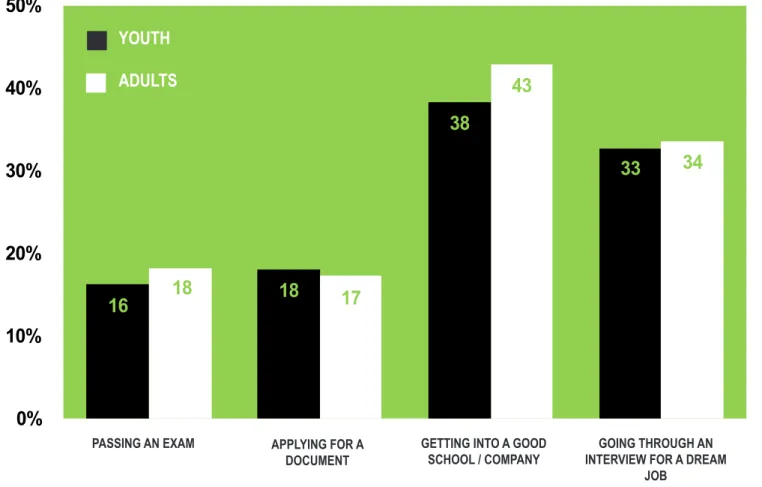

People’s actions are not always in line with their personal values. To better understand the relationship between ethical principles and the capacity to follow these up on the behavioural level, the YIS investigates youth exposure to corruption and their behaviour and reactions to such situations.Youth were surveyed on their experiences of corruption in six daily activities. As shown in figure 1, in five out of six situations, adults experience significantly less corruption than youth in the specific sectors they had contact with, confirming the assumption that youth are more vulnerable to corruption. Receiving medical treatment, encounters with the police and getting more business for one’s company are situations where overall youth face the most corruption.

19 23 33 37 21 29 19 7 22 19 12 2 0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 40% GET A DOCUMENT OR

A PERMIT PASS AN EXAM OR BE ACCEPTED IN A PROGRAM AT SCHOOL

GET MEDICINE OR

MEDICAL ATTENTION(E.G. A FINE) WITH THE AVOID A PROBLEM POLICE

GET A JOB GET MORE BUSINESS FOR ONE'S COMPANY

FIGURE 1

Experiences of corruption among those who have contact during the past 12 months:

youth versus adults

YOUTH

ADULTS

GET A DOCUMENT

OR PERMIT PASS AN EXAM OR BE ACCEPTED IN A PROGRAMME AT SCHOOL GET MEDICINE OR MEDICAL ATTENTION AVOID A PROBLEM (EG. A FINE) WITH

THE POLICE

GET A JOB GET MORE

BUSINESS FOR ONE’S COMPANY

16

18

38

33

18

17

43

34

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

YOUTH

ADULTS

PASSING AN EXAM GETTING INTO A GOOD

SCHOOL / COMPANY APPLYING FOR A

DOCUMENT INTERVIEW FOR A DREAM GOING THROUGH AN

JOB

These experiences match up to how youth rank the integrity of public institutions. 12% and 8% of youth rated the traffic police and public health care respectively as “very bad” marginally higher than their perception of the local/national administration and public education (both 5%).

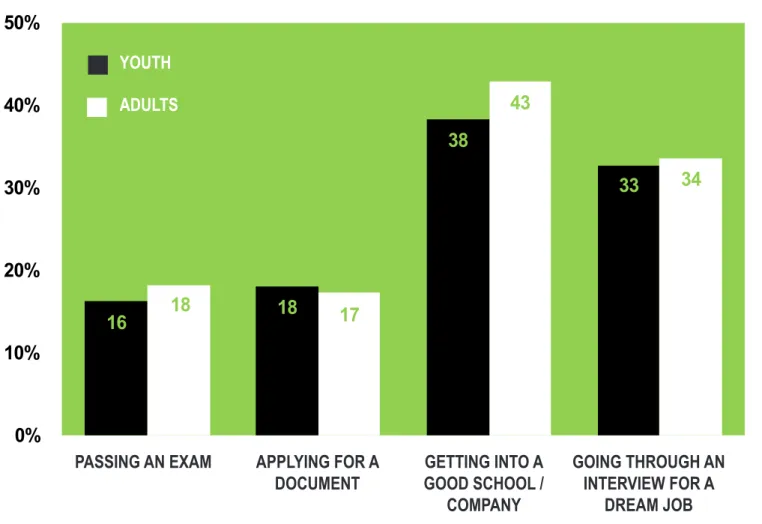

Figure 2 shows the percentage of youth who are willing to violate principles of integrity in the given situations. Youth were most likely to engage in corrupt practices in order to get into a good school or company or in an interview for a dream job, situations which are the most financially important for youth. A striking 38% of youth are ready to pay a bribe to get into a good school or company.

When it comes to fighting against corrupt practices, 86% of youth think they can play a role and around 60% of youth replied that they would report an incidence of corruption (out of them, only 4% already did so in the past). The main reasons for not reporting corruption are indifference (“it’s not my business”) and disillusionment (“it won’t help anyway”). Interestingly, there seems to be no difference in responses between youth who have previously been victims of corruption, compared to those who have not, perhaps illustrating that corruption has become institutionalised.

3.3 INFLUENCES ON YOUTH INTEGRITY

To understand why achievements in previous educational efforts have been limited and to identify more effective educational measures, the final part of the study looks at the different information sources influencing their understanding of integrity and anti-corruption, and how they impact on shaping the ethical views of youth.

In general, the four most important sources in shaping youth views on integrity are the TV and radio, cited by 89% of respondents, the learning environment (school or university) and family (both cited by 80% of respondents), and friends and colleagues (76%). Less than half of youth (39%) cite the internet as one of the sources shaping their views. Rural and poorer youth are much less susceptible to be influenced by the internet, newspapers and schools and universities. Despite the important influence of schools, only 17% of youth say that they received some form of education on integrity. Out of these, almost two thirds felt that such programmes were not helpful enough. The YIS consequently indicates that anti-corruption education thus far, has been largely unsuccessful in developing a generation of youth ready and equipped to fight against corruption.

4. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Apart from their experiences with corruption, youth responses did not generally vary greatly from adults. More significant differences were found between varying educational backgrounds. Less educated youth were more likely to have a less strict definition of integrity, to approve or accept corrupt behaviours and less likely to report cases of corruption. However the findings also show that compromising integrity is a learnt behaviour as youth are more willing to “relax” their principles as they grow older. This means that youth could play a greater role in promoting integrity.

If it is expected that the YIS will be used as a baseline to inform key stakeholders working to promote youth integrity, a number of initial broad recommendations can be put forward:

• Root integrity promotion and anti-corruption education in discussions about ethics.

• Target efforts to focus on the geographic groups and thematic sectors most prone to corruption, such as urban areas, the police or the health sector.

• Promote role models to change youth perception that success and integrity and honesty are often mutually exclusive.

• Target wider environmental influences including families. • Employ various forms of media, such as television, radio

and newspapers to influence youth on the importance of integrity.

• Teach concrete situations which young people may face in their daily life rather than only abstract behaviours. • Mobilise youth outside schools through extra-curricular

activities. To help overcome youth reluctance to become individually involved in the fight against corruption, greater support could be provided for group initiatives to capture the collective trust youth have in themselves to promote integrity.

• Improve the external environment to enable youth to refuse and report corruption and to restore the trust of youth. Greater efforts should be made to enforce existing policies, investigate suspects and sentence persons who have been found guilty of illegal acts.

• Reward youth who demonstrate integrity by offering them additional “opportunities” and support such as: scholarships for students, training courses, internships, awards and etc.

FIGURE 2

Willingness to take decisions which violate integrity in different situations:

1. INTRODUCTION

WHY THE VIETNAM YOUTH

INTEGRITY SURVEY (YIS) PILOT?

Corruption has been officially recognised by the Vietnamese authorities as a serious issue of concern for the development and stability of the country.1 In recent years, national anti-corruption efforts have been significantly strengthened towards giving more and more importance to the mobilisation of society and citizens in the prevention and fight against corruption.2 However, with over 55% of the population of Vietnam under 30 years old, youth must be prioritised as a target group for anti-corruption mobilisation activities. Not only do youth make up a significant proportion of the population, but international surveys have shown that youth are particularly vulnerable as victims of corruption.3 Changing youth attitudes and behaviours is thus imperative to ensure that anti-corruption achievements are sustainable.

At the same time, rapid economic growth in Vietnam has shaken social transition and transformation, with many people expressing concerns about the dissolution of “traditional values”. To improve anti-corruption efforts and respond to these concerns, the Prime Minister of Vietnam signed Project 137 in December 2009 to push the introduction of anti-corruption curricula in schools and universities. This initiative offers the opportunity to influence the values of young people and make a concrete change. However to ensure that the curriculum is effective, institutions must first be better positioned to understand and assess the beliefs, behaviours and experiences related to the integrity of young Vietnamese. Improved understanding will also better inform the development of adapted policy interventions targeting young people, to empower them to contribute more to promoting integrity, transparency and anti-corruption efforts.

For these reasons, in the framework of the Transparency International (TI) Vietnam Programme, youth has been identified as one of the key sectoral focus for TI emerging activities in Vietnam. The Vietnam YIS pilot, coordinated by Towards Transparency (TT), has been one of the key

priorities, commitments and achievements of the TI Vietnam Programme since its implementation in 2009.

The Vietnam YIS pilot project, interviewing more than 1,000 Vietnamese youth from 15 to 30 years old randomly chosen from 11 provinces,4 will assist TI and TT to design relevant activities related to youth. More fundamentally, however, this report is intended as a guide to support all institutions (specifically Vietnamese institutions in charge of youth education, such as the Ministry of Education and Training, the Youth Union and etc) that play an important role in shaping the views and attitudes of youth. The findings of the Vietnam YIS pilot can contribute extensively to the development of activities related to promoting improved integrity amongst Vietnamese youth. This survey should be used as a baseline and repeated over coming years to observe the change in youth integrity, and particularly the impact of policies and initiatives related to this area.

The Vietnam YIS pilot is strongly supported by extensive international experience from the TI movement, which has placed great attention on youth since TI’s establishment in 1993. Youth has been a key focus area for many TI chapters around the world. The number of activities to mobilise youth in promoting integrity and anti-corruption has been growing, taking different forms depending on the local context and innovative initiatives available.5 These experiences have demonstrated that youth mobilisation can make a difference in anti-corruption.6

To inform the design of such interventions, TI has placed great emphasis on developing scientifically stronger research tools to document youth beliefs, behaviours and experiences related to integrity. The TI-Secretariat and a number of key national chapters active in youth work in the Asia-Pacific region agreed to review the original methodology of previous research on youth integrity and address identified shortcomings before rolling out the emerging tool regionally and internationally within the TI movement. It was suggested that the TI Vietnam Programme could lead this review and pilot the new methodology in Vietnam.

THE PROCESS OF DEVELOPING

THE NEW METHODOLOGY: A

COLLABORATIVE APPROACH

The process of developing the YIS methodology and questionnaire has been led and coordinated by Ms Nguyen Thi Kieu Vien and Mr Matthieu Salomon from TT. The main ideas and dimension of the Vietnam YIS pilot came from the previous initiatives of TI chapters, particularly the Youth Integrity Index produced by TI Korea. In order to strengthen the tool, researchers from the DIAL team in Hanoi, Dr. Mireille Razafindrakoto and Dr. Francois Roubaud, who are familiar with both TI’s tools and the Vietnamese context, were commissioned to review the previous research methodology.7 At the same time, TI and TT started to collaborate very closely with Dr Dang Dinh and Dr. Dang Giang from the Vietnamese non-governmental research center – Center for Community Support Development Studies (CECODES), on this project, in order to ensure that the new YIS methodology and questionnaire would be relevant and easily adaptable for a pilot survey in Vietnam. This collaboration brought strong local Vietnamese experience and expertise in research on governance topics to the new methodology. Researchers from the Youth Research Institute (YRI)8 also took an active part in these discussions and gave valuable inputs in the process.

In this regard the Vietnam YIS pilot is the result of a very close collaboration between international and local expertise. In December 2009, a regional workshop was organised in Bangkok, Thailand, where representatives from TI Korea, TI Bangladesh, TI Secretariat, DIAL, CECODES,

YRI and TT discussed these previous and new tools in depth to understand and assess youth beliefs, behaviours and experiences related to integrity. This workshop was instrumental in developing the Vietnam YIS pilot questionnaire and methodology. These were finalised in June 2010, after broad consultation with Vietnamese partners, TI chapters and the TI Secretariat’s Policy and Research Department, as well as intense and lively discussions amongst the organisations involved, and some concrete testing of the questionnaire organised by CECODES and the YRI with youth groups in Hanoi. Chapter 2 and Annex 2 provide more detail on the methodology of the Vietnam YIS pilot.

To conduct the field work, TI, TT and CECODES partnered up with the Vietnamese NGO Live&Learn and its network of young people committed to promoting improved transparency in Vietnamese society.9 In a conscious decision to ensure that the interviewees would be comfortable during the interviews and to use the interview process as an additional means to promote awareness of youth integrity, interviews were conducted by young volunteers, students or recent graduates. The field work was coordinated by Ms Nguyen Thuy Hang from Live&Learn.

Thus this report is foremost the result of a very fruitful and collective effort involving local and international partners. The Vietnam YIS pilot provides a comprehensive, complicated and nuanced image of youth integrity in Vietnam that will help different stakeholders in their engagement with youth and in their efforts to promote stronger youth integrity. In addition, the study has also collected a wealth of valuable quantitative data not previously available, which can be used for further research in the future.10

2. THE METHODOLOGY

THE CONCEPT

The concept of the research is based on the definition of integrity as “[b]ehaviours and actions, consistent with a set of moral and ethical principles and standards, embraced by individuals as well as institutions, that create a barrier to corruption” provided by TI (Transparency International Plain Guide Language, 2009). Consequently, the YIS pays special attention to corruption issues11 covering the way youth understand the concept of integrity, their awareness and perception of situations involving corruption, their attitudes, behaviours and actions when faced with corruption, and explores which actors have the most influence on shaping youth values and behaviours. Given that youth do not live in a vacuum, this information is crucial in order to understand why achievements in previous educational efforts have been limited and to identify and suggest more effective education measures.

The YIS research team chose to present the broad range of information provided by the survey in a comprehensive and detailed written analysis, rather than computing the data in the form of a youth integrity index. It was feared that an index would put too much emphasis on classifications and ranks, obscuring the important details explaining the specific context of the country. Furthermore, there was a concern that when the YIS is replicated in other countries, an index would create a tendency to put countries into competition with one another, impeding the way youth integrity should be understood and analysed.

THE SAMPLING DESIGN

The research covered young people between 15-30 years old to allow conformity with both the Vietnamese classification of youth (16-30 years), and the international definition (15-24 years). In order to explore potential differences between youth attitudes, behaviours and values from the rest of the population, the research sampled a control group of adults over 30 years old.

Throughout this report, whenever the term “youth” is used, it refers to the target group (aged 15-30). The term “adult” refers to the control group (respondents over 30 years old).

Following international statistical standards, the YIS used a multi-staged sampling design, selecting 12 provinces in 6 socio-economic regions of the country, each province containing 3 rural and 3 urban sampling points. Respondent lists were produced based on data from the 2009 Census by the General Statistics Office (GSO). In total, face to face interviews were conducted with 1022 youths aged 15-30 (the target group), and 519 adults aged over 30 (the control group).

Key demographic parameters of the sample, such as age and gender distribution, employment status and etc. are provided in Annex 1.

Much of the analysis in the report classifies respondents based on their education levels and living standards.

With regards to education, four groups are defined as follows: (i) Up to completing primary school; (ii) Up to completing lower secondary school; (iii) Up to completing upper secondary school; and (iv) Above upper secondary school education. Within the report, references to the “least educated” refers to respondents which have only studied up to the end of primary school and references to the “best educated” refers to respondents who have received post-upper secondary school education.

With regards to living standards, four groups of respondents are defined based on their self-perception of their own economic situation: (i) Living well; (ii) More or less alright; (iii) Alright but need to be careful with money; (iv) Living with difficulty. Within the report, references to the “worst off” refers to the group which is living with difficulty and references to the “best off” refers to respondents who say they are living well. Responses were also analysed with respect to the age (looking at different age groups of youth), gender, occupation, geography (urban versus rural residences) and the ethnicity12 of the respondents.

THE QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN

The questionnaire considered four different dimensions of the concept of integrity:

• Morality and ethics – the conceptual understanding of standards of behaviour;

• Principles – the ability to differentiate between what is right and what is wrong;

• Respect for laws – the degree of compliance with the legal framework set forth by society; and

• Resistance to corruption – the ability to challenge corrupt practices.

It dealt with both questions on opinions and perceptions, as well as questions on experiences and behaviours. Questions on opinions and perceptions seek to capture the global understanding of the concept of integrity, while the questions on experiences and behaviour measure the extent to which respondents put notions of integrity into practice in their daily life.

Designed to roll out internationally, the questionnaire includes three parts. The core part covers the main basic questions (10 questions) to be asked in every implementing country in order to allow international comparisons and to provide the fundamental basis for a global and/or regional Youth Integrity Promotion Programme. An optional, second part with more specific questions allows for the collection of more detailed information (7 questions) to provide greater insights. The third part, also optional and to be developed in the context of each country, aims at including more country specific questions, addressing particular laws or evaluating specific policies (2 questions). The Vietnam 2010 survey included all three parts of the questionnaire.

THE FIELD WORK

The field work was carried out between August and December 2010 by Live&Learn, with the facilitation of CECODES and collaboration with provincial chapters of the Vietnam Fatherland Front (VFF). Young volunteers, mostly students and recent graduates, were recruited and trained to conduct the interviews.

Interviews took place in a neutral setting, such as a cultural house or in the home of respondents. Special attention was paid to avoid potential disturbances created by the presence of other people, especially public officials.

Due to logistical problems, the research team was not able to conduct the survey in one province. The number of observations in each province was thus increased in the remaining 11 provinces in order to achieve the planned total. In the end, surveys were undertaken in Hai Duong, Nam Dinh, Nghe An, Dien Bien, Lam Dong, Gia Lai, An Giang, Ho Chi Minh City, Long An, Binh Duong and Quang Ngai.

As the sampling was based on the 2009 census, there were also additional challenges in reaching all the people on the list, as some had migrated for work or study in the time following the census.

With its sampling design, the Youth Integrity Survey is one of the first surveys in Vietnam looking at integrity, which not only employs a rigorous scientific approach, but also covers both urban and rural population.

AN GIANG HO CHI MINH BINH DUONG DIEN BIEN HAI DUONG

LAM DONG LONG AN NAM DINH NGHE AN QUANG NGAI GIA LAI

VALUES

The survey approaches this broad area by aiming to see the importance that youth assign to integrity in comparison to wealth and success. Respondents are asked to give their part or total agreement to two opposite statements:“Being rich is the most important and it is acceptable to lie or cheat, ignore some laws and abuse power to attain this objective”opposed to“Being honest is more important than being rich”.13

% of respondents who totally agree that being rich is most important and it is acceptable to lie or cheat to attain this objective

% of respondents who partly agree that being rich is most important and it is acceptable to lie or cheat to attain this objective

% of respondents who partly agree that being honest is more important than being rich

% of respondents who totally agree that being honest is more important than being rich

2 3 3 4 34 26 61 68 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% YOUTH ADULT

3. KEY FINDINGS

The clash between material advantage and integrity is formulated in a slightly different way. The survey asks respondents for their partial or total agreement on either the statement that “Finding ways to increase family income has the highest importance and it is acceptable to ignore some laws and abuse power to attain this objective”, or the statement that “Being honest and respecting laws and regulations are more important than increasing family income”.14

% of respondents who totally agree that finding ways to increase family income has the highest importance and it is acceptable to ignore some laws and abuse power to attain this objective

% of respondents who partly agree that finding ways to increase family income has the highest importance and it is acceptable to ignore some laws and abuse power to attain this objective

% of respondents who partly agree that being honest and respecting laws and regulations are more important than increasing family income

% of respondents who totally agree that being honest and respecting laws and regulations are more important than increasing family income As shown in Figure 3, 4 and 5A (on the next page), the majority of responses from both youth and adults are generally aligned with socially accepted views on honesty and integrity. Out of the total number of youth surveyed, 95% partly or totally agree that being honest is more important than being rich, 89% with the statement that being honest is more important than increasing income, and 82% with the statement that an honest person has more chance of success – meaning at the same time, however, that 17% of youth believe that cheating is more likely to lead to success than honesty (see next page). Interestingly, youth seem more likely to take a central position (either only partly agreeing or partly disagreeing) than adults, especially when the subject is on wealth or income versus integrity.

3 3 6 7 29 21 60 69

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

YOUTH

ADULT

3.1 YOUTH VALUES AND ATTITUDES

TOWARDS INTEGRITY

The starting point of the research is to look at the values and attitudes of youth in Vietnam today. It is important to investigate questions such as what they consider to be right or wrong, which acts they perceive as corrupt, how they understand the concept of integrity and how integrity is positioned in their value system in comparison to family loyalty, financial wealth and success. The exploration of these questions contributes to a greater understanding of the thoughts and the social interaction of youth today. This is the first key step of any educational programme which not only aims to be successful in changing youth values, but actually empowers youth to also change society.

FIGURE 3

Values on wealth, success and integrity (wealth versus honesty):

youth versus adults

FIGURE 4

Values on wealth, success and integrity (income versus honesty):

youth versus adults

YOUTH

ADULT

YOUTH

ADULT

Finally, the last question in the set looks at what youth consider to be the key ingredients of success and asks for total or partial agreement on two statements: “People ready to lie, cheat, break laws and be corrupt are more likely to succeed in life” versus “An honest person, with personal integrity, has more or as much chance to succeed than a person who lacks integrity”.15

Overall, the figures were fairly consistent between youth and adults. As shown in Figure 5A, only 5% of youth totally or partly agree that being rich is most important and that it is acceptable to lie or cheat, ignore some laws and abuse power to attain this objective, slightly less than the number of adults who agreed (7%). Among the youth surveyed, answers to the questions were also fairly consistent across age groups, gender, occupation and geography (urban versus rural residence). For this question, differences

between respondents who consider themselves to be living with financial difficulty (worst off) and those who consider themselves to be living well (best off) are not large (4% versus 2%). Differences were also small between respondents classified as the least educated (those who studied up to the end of primary school) and those classified as the best educated (those who have undertaken post-upper secondary school education) (6% versus 4%).

% of respondents who partly or totally agree that being rich is most important and it is acceptable to lie or cheat, ignore some laws and abuse power to attain this objective

% of respondents who partly or totally agree that finding ways to increase family income has the highest importance and it is acceptable to ignore some laws and abuse power to attain this objective

% of respondents who partly or totally agree that people ready to lie, cheat, break laws and be corrupt are more likely to succeed in life

FIGURE 5A

Values on wealth and success and integrity:

youth versus adults

% of respondents who partly or totally agree that being rich is most important and it is acceptable to lie or cheat, ignore some laws and abuse power attain this objective

% of respondents who partly or totally agree that finding ways to increase family income has the highest importance and it is acceptable to ignore some laws and abuse power to attain this objective

% of respondents who partly or totally agree that people ready to lie, cheat, break laws and be corrupt are more likely to succeed in life

Given that being rich is a broad and abstract concept, whilst increasing family income is much more concrete and tangible, it is natural that more youth are willing to sacrifice honesty to increase their family’s income compared to the number willing to sacrifice honesty to be rich. In this case, the proportion of youth almost doubles to 9% (compared to 10% among adults). Interesting patterns start to emerge when we compare answers to this question by the economic situation of respondents. Responses were notably higher amongst the worst off (10% agreed compared to only 5% of the best off) and least educated (12% compared to 6% of the best educated).

Responses to the final question of this set are particularly troublesome. Not only do 17% of young people believe that cheating, breaking the law and being corrupt increase your chances of being successful, but this is the only category where there is greater agreement amongst the more educated and better off respondents. A striking 25% of the best educated (and 22% of the best off) believe that a person

with integrity has less chance to succeed in life. There are also sharp divides between responses from urban and rural citizens, as well as between Kinh and minority populations. The survey found that 23% of youth in urban areas believe that cheating increases your chances of being successful, compared to only 15% of youth in rural areas. The percentage among Kinh youth is 19% versus 12% among young ethnic minority populations. However diverging responses between ethnic and geographic differences may merely be a reflection of the fact that a higher concentration of the better off and better educated population live in urbanities and belong to the Kinh population.

It is deeply concerning that the group with the greatest intellectual potential, who are also the most likely to enter future leadership positions share a particularly cynical idea of the rules of life and society, especially given that the best educated and the best off normally have more exposure to examples of people who have achieved success.

4

2

6

4

10

5

12

6

13

22

11

25

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

WORST OFF

BEST OFF

UP TO PRIMARY

ABOVE UPPER

SECONDARY

FIGURE 5B

Youth values on wealth, success and integrity:

broken down by living standards and education

levels

LEAST

EDUCATED

EDUCATED

BEST

5

7

9

10

17

14

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

YOUTH

ADULT

53

69

26

16

12

6

9

8

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

ATTITUDE TO INTEGRITY

To complement these insights into value systems and ethical standards, the YIS also explored youth understanding of the concept of integrity. It did so by presenting a range of corrupt behaviours and asking the respondent whether they (a) think it is a wrong behaviour and (b) would accept the behaviour.16 The range of corrupt behaviours given vary from abstract propositions, such as “a leader does something which might be illegal but it enables your family to live better”, to concrete everyday life situations, such as “a person gives an additional payment or a gift to a doctor or nurse in order to get better treatment”.

The list of behaviours is provided below:

a. A person does something which might be illegal in order to make his/her family live better

b. A leader does something which might be illegal but it enables your family to live better

c. A public official requests an additional unofficial payment for some service or administrative procedure that is part of his job (for example to deliver a licence)

d. A person having responsibility gives a job in his service to someone from his family who does not have adequate qualifications (to the detriment of a more qualified person)

e. A person gives an additional payment (or a gift) to a public official in order to speed up and facilitate the procedure of registering a car or a motorbike f. A person gives an additional payment (or a gift) to a

doctor or nurse in order to receive better treatment g. A parent of student gives an additional unofficial

payment (or a gift) to a teacher so that their child can get better grades

As shown in Figure 6 below, around 53% of youth consider all seven behaviours to be wrong. 26% makes one exception, and 21% see two or more of the seven behaviours as not wrong. Adults seem to be stricter: 69% of them reject all seven behaviours as wrongful acts.

% OF RESPONDENT AGREEING THE

CORRUPT BEHAVIOUR IS WRONG YOUTH ADULTS BEST OFF WORST OFF BEST EDUCATED LEAST EDUCATED

Average of each of the seven behaviours 88 91 82 88 91 83

Giving extra payment to get better

treatment 68 82 58 69 64 68

TABLE 1

Attitude to integrity- average perception of corrupt behaviours (disaggregated view)

Across each of the hypothetical situations given, an average of 88% of youth said they considered each of the seven behaviours to be wrong, almost the same proportion as the control group of adults where an average of 91% of respondents perceived each behaviour to be wrong. An exception exists for the statement related to bribery to receive better medical treatment, where youth appear to be more flexible. Within youth there is also no significant difference in responses between genders, geographic spread (rural versus urban), occupations or ethnicities.

There are, however, slight differences between both educational levels and self-perceived living standards. Significantly more youth who are worst off view requesting bribes for the completion of administrative services by public officials and the payment of bribes for better medical services as wrong, while their response to other situations were more aligned. A possible explanation for this is that these two forms of petty corruption are among the most wide-spread with the greatest impact on the poor, while those who are better off can use their financial leverage to deal with these situations.

The gap between educational levels is greater – those with less education seem to be more flexible: among the least educated, an average of only 83% considered the behaviours to be wrong compared to an average of 91% of the best educated. The largest differences are found in statements related to: a person breaking the law to make his/her family’s life better, a leader breaking the law although it makes the respondent’s family’s life better, nepotism in recruitment, and bribery to speed up an administrative procedure. On the other hand, responses to the statement related to bribery to receive better medical treatment are quite similar.

Among the situations in question, a significantly higher number of youth do not consider it to be wrong to give “additional payments or gifts in a hospital in order to get better treatment”: only 68% of youth in general consider it to be wrong, significantly lower than the percentage of adults at 82%. This number is fairly consistent across different groups of youth, except when we compare responses by living standards: among the best off youth, the number is as low as 58%, meaning that almost one out of two people in this group consider the payment of bribes for better medical treatment as “normal”. Willingness to engage in informal payments in health services may be explained by the fact that health is far more important than attaining a driving license or passing a school exam. Thus, the more easily people can afford informal payments, the more willing they are to pay for it.

FIGURE 6

Attitude to integrity- average perception of corrupt behaviours:

youth versus adults

CONSIDER ALL 7 BEHAVIOURS TO BE WRONG

CONSIDER 6 BEHAVIOURS TO BE WRONG

CONSIDER ALL 5 BEHAVIOURS TO BE WRONG

CONSIDER 4 OR LESS BEHAVIOURS TO BE

WRONG

YOUTH

ADULT

17

9

11

9

8

7

74

83

82

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

FIGURE 7

Averaged youth acceptance of corrupt behaviours:

broken down by education levels

The second part of the question adds on a differentiation and asks if respondents find the same behaviours to be acceptable, even if they think they are wrong. Figure 7 shows the results of average youth responses according to education backgrounds, broken down to three groups: those who do not think that the behaviour is wrong, those who think that it is wrong but still acceptable, and those who think that the behaviour is both wrong and unacceptable.

On average for all seven behaviours in question, 82% of youth find the behaviour to be wrong and unacceptable, while 7% know that these actions are wrong but are still willing to accept them. Finally, 11% do not consider the acts to be problematic at all. As shown above, the less educated are much more willing (26%) to accept the corrupt behaviours as either not wrong or still acceptable. This attitude perhaps reflects their personal experiences on how “the system works.” Even more concerning, it perhaps demonstrates that this group feels “excluded” and do not see any alternative solution to cope with their daily challenges without resorting to corruption. In any case, it also indicates that ethical education has failed to the greatest extent amongst this group. In later

parts, the study looks at which information sources which actors in society have the biggest impact on shaping the views of different youth groups. This information will hopefully help to design more effective educational programmes. On the question of “acceptance”, there are no big differences between gender, age groups, occupation, religion or

geography. The only significant gaps exist between respondents from minority population (27%) and the Kinh population (16%), which again may be due to the fact that there is a significant overlap between those who are less educated and those from ethnic minorities.

YOUTH IN GENERAL

BEST EDUCATED

LEAST EDUCATED

NOT WRONG

WRONG BUT ACCEPTABLE

WRONG AND NOT ACCEPTABLE

FIGURE 8

Youth perception on giving extra payment to receive better medical treatment

Again, readiness to compromise when health is involved is by far greater than in all other situations. As shown in Figure 8, only around half of the young people surveyed see the act of giving an extra payment to receive better medical treatment as unacceptable. 13% of them admit it is not a proper

behaviour, but are still willing to accept it, and as much as one third of all youth (32%) do not even consider such an action to be wrong. The total proportion of youth (45%) willing to accept bribes for better medical attention is significantly larger than the proportion of adults (30%). Among youth, this perception is quite consistent and does not vary much between gender, living standards or education levels. There does however exist a sharp gap between different age groups: 50% of the youngest group (15-18 years old) accept the practice compared to 41% of the oldest group (26-30 years old). The fact that corruption is widely accepted in certain areas such as health care and is seen to be a normal part of life by all groups of the population will make fighting corruption in these cases very challenging.

32%

13%

55%

NOT WRONG

WRONG BUT ACCEPTABLE

WRONG AND NOT

ACCEPTABLE

NOT WRONG

WRONG BUT

ACCEPTABLE

WRONG AND NOT

ACCEPTABLE

72 63 62 70 27 31 27 24 1 7 11 6 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

LEAST EDUCATED

93 87 92 92 7 11 6 6 1 1 2 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%BEST EDUCATED

84 78 83 86 80 76 79 83 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%FIGURE 9A

Lack of integrity as a serious problem:

youth versus adults

PERCEPTIONS ON THE

IMPORTANCE OF INTEGRITY

While the majority of youth reject examples of corrupt behaviours as both wrong and unacceptable (as previously shown in figure 7), what are their views on the importance of integrity and the impact of lack of integrity?

For this purpose, respondents were asked if they perceived lack of integrity (including corruption) to be a major problem for (i) youth; (ii) their family and friends; (iii) business / the economy in general; and (iv) the country’s development.17 The absolute majority of youth, between 83% and 86%, believe that lack of integrity is very harmful for their

generation, the economy and the development of the country. Interestingly, “only” 78% think that a lack of integrity has a direct impact on their family and friends. The adult control group has very similar responses. These results indicate that corruption seems to continue to be perceived as a somewhat abstract issue, and while both youth and adults recogonise that it is bad for the country at large, they are less able to perceive its impact on their direct social environment.

A number of differences can be noticed between the

responses of various groups of youth. While 90% of the better off perceive lack of integrity to be harmful to the country’s development, only 81% of poorer youth make the same connection. The difference is even greater when we compare respondents by their educational levels: the more education young people receive, the more likely they are to perceive the negative impact of lack of integrity, both for their own social circles and for the wider society at large. Inversely, less educated youth are less likely to perceive its negative impact and are also more likely to reply that they do not know whether a lack of integrity is a serious issue. Figure 9A shows the striking differences between the most and the least educated groups of youth.

Only between 62% and 72% of the least educated believe that lack of integrity is harmful, compared to between 87% and 93% of the best educated. Almost one third of the least educated youth believe that lack of integrity has no serious impact on their family and friends. In addition, 11% and 6% of this group are not sure about its impact on the economy and the country’s development respectively, while among the best educated, less than 2% did not have an opinion. Particular attention should be paid to those without an opinion, as they could potentially turn into informed citizens through proper educational measures.

Finally, there is a significant gap in perceptions between youth from urban and rural areas, which may be a reflection of the educational divide: 85% of urban and only 75% of rural youth believe that lack of integrity negatively impacts their family and friends; 94% of urban versus only 83% of rural youth think that lack of integrity is bad for the country. Similarly, minorities have a much lower awareness compared to the Kinh youth population: 74% of the former compared to 89% of the latter are critical of the impact lack of integrity has on the country’s development. Interestingly, on average, younger youth are also much more aware of corruption’s negative impact than older youth. For example, 87% of youth between 15-18 years old believe that lack of integrity has a negative impact on youth, while “only” 77% of the youth between 26-30 years old make the same connection.

FIGURE 9B

Lack of integrity as a serious problem:

broken down by education levels

NO

YES

DON’T KNOW

FOR COUNTRY’S DEVELOPMENT

FOR COUNTRY’S DEVELOPMENT

FOR ECONOMY

FOR ECONOMY

FOR FAMILY AND FRIENDS

FOR YOUTH

FOR FAMILY AND FRIENDS

FOR YOUTH

YOUTH

ADULTS

FOR YOUTH

FOR FAMILY

AND FRIENDS

FOR ECONOMY

FOR COUNTRY’S

DEVELOPMENT

LEAST EDUCATED

45 30 28 6 50 27 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 35 41 16 25 36 44 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50%

Figure 10A shows that in general, around one third of youth (35-36%) are ready to relax their definition of integrity and make exceptions if exercising principles of integrity results in financial disadvantages, will help in solving a problem or if the amount of bribe changing hands is small. 16% of youth are even ready to break the law in solidarity with their family and friends.

Adults are even more willing to compromise their integrity: almost half of the adults surveyed do not perceive the payment or receipt of small amounts of bribes to be problematic, and one fourth (25%) are ready to commit an unlawful act in support of their family and friends.

This difference is also prevalent among different age groups with youth becoming more willing to compromise their integrity as they grow older. Responses from youth aged between 26-30 years are very similar to the adult group, while the readiness of youth aged between 15-18 years to compromise their integrity is lower than the overall youth average. This indicates that compromising integrity is actually a process which develops as youth get older, where the principles that the youngest learn (and are ready to follow) are progressively being eroded and corrupted as they grow older, by their experiences of how the society concretely functions. This finding demonstrates that the more social and professional interaction a young person experiences, the more willing they are to relax their own definition of integrity.

READINESS TO COMPROMISE

INTEGRITY

How ready are young people to compromise their integrity if being honest involves a personal loss that impacts them either financially or socially? How ready are they to compromise their ethical values? The YIS assessed the difference between theoretical understandings of integrity and how ready young people are to make exceptions to this understanding. Respondents were asked to give their agreement to three definitions of a person of integrity.18 The definitions are somebody who:

i. Never lies nor cheats so that people can trust him/her ii. Never break the law in any case

iii. Never accepts nor gives bribes

Not surprisingly, 92% to 94% of youth have no problem in agreeing with these theoretical definitions. In addition, no significant variation exists between different gender, geographical divide, living standard or education levels, or between youth and the adult control group.

However, differentiations start to emerge when we analyse how ready respondents are to compromise their definition of integrity. For this purpose, three similar, but relaxed definitions of a person of integrity were offered as someone who19:

i. Does not lie nor cheat except when it is costly for him/ her or his/her family

ii. Demonstrates solidarity and support to family and friends in all manners even if that means breaking the law

iii. Refuses to pay or receive a bribe except when the amount is small or to solve a difficult problem

FIGURE 10A

Agreement with a “relaxed” definition of integrity:

youth versus adults

FIGURE 10B

Agreement with a “relaxed” definition of integrity:

broken down by education levels

Are those with less education less aware of the consequences and the harmfulness of their acts, or have they learned that this is the way they have to go through life? Or, once again, do they feel that they simply do not have any alternatives to overcome their daily challenges?

When broken down by occupation, unemployed and job seeking youth demonstrate a much higher readiness to relax their definition of integrity compared to youth who are employed or currently undertaking training or education. The reasons for this difference are probably easily understood. On the other hand, living standards do not appear to have a clear impact on responses. It is possible that education rather than economic pressure have a greater influence on youth attitudes and values.

Among youth, responses do not vary greatly between different genders and living standards (except that the worst off seem slightly more ready to accept small bribes). However, the divide between educational levels is striking. 45% of the least educated versus 30% of the best educated are ready to lie or cheat when it helps themselves or their family. Half of the least educated youth find it acceptable to engage in petty corruption, compared to 27% of the best educated. When it comes to breaking the law in support of their family and friends, only 6% of the best educated are ready to do it, compared to 28% of the least educated (Figure 10B).